Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Immune system

View on Wikipedia

| Immune system | |

|---|---|

A scanning electron microscope image of a single neutrophil (yellow/right), engulfing anthrax bacteria (orange/left) – scale bar is 5 μm (false color) | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D007107 |

| FMA | 9825 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria, and parasites, as well as cancer cells and objects, such as wood splinters—distinguishing them from the organism's own healthy tissue. Many species have two major subsystems of the immune system. The innate immune system provides a preconfigured response to broad groups of situations and stimuli. The adaptive immune system provides a tailored response to each stimulus by learning to recognize molecules it has previously encountered. Both use molecules and cells to perform their functions.

Nearly all organisms have some kind of immune system. Bacteria have a rudimentary immune system in the form of enzymes that protect against viral infections. Other basic immune mechanisms evolved in ancient plants and animals and remain in their modern descendants. These mechanisms include phagocytosis, antimicrobial peptides called defensins, and the complement system. Jawed vertebrates, including humans, have even more sophisticated defense mechanisms, including the ability to adapt to recognize pathogens more efficiently. Adaptive (or acquired) immunity creates an immunological memory leading to an enhanced response to subsequent encounters with that same pathogen. This process of acquired immunity is the basis of vaccination.

Dysfunction of the immune system can cause autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases and cancer. Immunodeficiency occurs when the immune system is less active than normal, resulting in recurring and life-threatening infections. In humans, immunodeficiency can be the result of a genetic disease such as severe combined immunodeficiency, acquired conditions such as HIV/AIDS, or the use of immunosuppressive medication. Autoimmunity results from a hyperactive immune system attacking normal tissues as if they were foreign organisms. Common autoimmune diseases include Hashimoto's thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus type 1, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunology covers the study of all aspects of the immune system.

Layered defense

[edit]The immune system protects its host from infection with layered defenses of increasing specificity. Physical barriers prevent pathogens such as bacteria and viruses from entering the organism.[1] If a pathogen breaches these barriers, the innate immune system provides an immediate, but non-specific response. Innate immune systems are found in all animals.[2] If pathogens successfully evade the innate response, vertebrates possess a second layer of protection, the adaptive immune system, which is activated by the innate response.[3] Here, the immune system adapts its response during an infection to improve its recognition of the pathogen. This improved response is then retained after the pathogen has been eliminated, in the form of an immunological memory, and allows the adaptive immune system to mount faster and stronger attacks each time this pathogen is encountered.[4][5]

| Innate immune system | Adaptive immune system |

|---|---|

| Response is non-specific | Pathogen and antigen specific response |

| Exposure leads to immediate maximal response | Lag time between exposure and maximal response |

| Cell-mediated and humoral components | Cell-mediated and humoral components |

| No immunological memory | Exposure leads to immunological memory |

| Found in nearly all forms of life | Found only in jawed vertebrates |

Both innate and adaptive immunity depend on the ability of the immune system to distinguish between self and non-self molecules. In immunology, self molecules are components of an organism's body that can be distinguished from foreign substances by the immune system.[6] Conversely, non-self molecules are those recognized as foreign molecules. One class of non-self molecules are called antigens (originally named for being antibody generators) and are defined as substances that bind to specific immune receptors and elicit an immune response.[7]

Surface barriers

[edit]Several barriers protect organisms from infection, including mechanical, chemical, and biological barriers. The waxy cuticle of most leaves, the exoskeleton of insects, the shells and membranes of externally deposited eggs, and skin are examples of mechanical barriers that are the first line of defense against infection.[8] Organisms cannot be completely sealed from their environments, so systems act to protect body openings such as the lungs, intestines, and the genitourinary tract. In the lungs, coughing and sneezing mechanically eject pathogens and other irritants from the respiratory tract. The flushing action of tears and urine also mechanically expels pathogens, while mucus secreted by the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract serves to trap and entangle microorganisms.[9]

Chemical barriers also protect against infection. The skin and respiratory tract secrete antimicrobial peptides such as the β-defensins.[10] Enzymes such as lysozyme and phospholipase A2 in saliva, tears, and breast milk are also antibacterials.[11][12] Vaginal secretions serve as a chemical barrier following menarche, when they become slightly acidic, while semen contains defensins and zinc to kill pathogens.[13][14] In the stomach, gastric acid serves as a chemical defense against ingested pathogens.[15]

Within the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts, commensal flora serve as biological barriers by competing with pathogenic bacteria for food and space and, in some cases, changing the conditions in their environment, such as pH or available iron. As a result, the probability that pathogens will reach sufficient numbers to cause illness is reduced.[16]

Innate immune system

[edit]Microorganisms or toxins that successfully enter an organism encounter the cells and mechanisms of the innate immune system. The innate response is usually triggered when microbes are identified by pattern recognition receptors, which recognize components that are conserved among broad groups of microorganisms,[17] or when damaged, injured or stressed cells send out alarm signals, many of which are recognized by the same receptors as those that recognize pathogens.[18] Innate immune defenses are non-specific, meaning these systems respond to pathogens in a generic way.[19] This system does not confer long-lasting immunity against a pathogen. The innate immune system is the dominant system of host defense in most organisms,[2] and the only one in plants.[20]

Immune sensing

[edit]Cells in the innate immune system use pattern recognition receptors to recognize molecular structures that are produced by pathogens.[21] They are proteins expressed, mainly, by cells of the innate immune system, such as dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells,[19][22] to identify two classes of molecules: pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are associated with microbial pathogens, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are associated with components of hosts' cells that are released during cell damage or cell death.[23] Cells in the innate immune system have pattern recognition receptors that detect internal infection or cell damage. Three major classes of these "cytosolic" receptors are NOD–like receptors, RIG (retinoic acid-inducible gene)-like receptors, and cytosolic DNA sensors.[24]

Recognition of extracellular or endosomal PAMPs is mediated by transmembrane proteins known as toll-like receptors (TLRs).[25] TLRs share a typical structural motif, the leucine rich repeats (LRRs), which give them a curved shape.[26] Toll-like receptors were first discovered in Drosophila and trigger the synthesis and secretion of cytokines and activation of other host defense programs that are necessary for both innate or adaptive immune responses. Ten toll-like receptors have been described in humans.[27]

Innate immune cells

[edit]

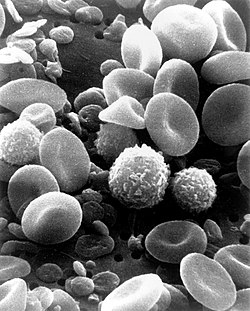

Some leukocytes (white blood cells) act like independent, single-celled organisms and are the second arm of the innate immune system. The innate leukocytes include the "professional" phagocytes (macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells). These cells identify and eliminate pathogens, either by attacking larger pathogens through contact or by engulfing and then killing microorganisms. The other cells involved in the innate response include innate lymphoid cells, mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and natural killer cells.[28]

Phagocytosis is an important feature of cellular innate immunity performed by cells called phagocytes that engulf pathogens or particles. Phagocytes generally patrol the body searching for pathogens, but can be called to specific locations by cytokines.[29] Once a pathogen has been engulfed by a phagocyte, it becomes trapped in an intracellular vesicle called a phagosome, which subsequently fuses with another vesicle called a lysosome to form a phagolysosome. The pathogen is killed by the activity of digestive enzymes or following a respiratory burst that releases free radicals into the phagolysosome.[30][31] Phagocytosis evolved as a means of acquiring nutrients, but this role was extended in phagocytes to include engulfment of pathogens as a defense mechanism.[32] Phagocytosis probably represents the oldest form of host defense, as phagocytes have been identified in both vertebrate and invertebrate animals.[33]

Neutrophils and macrophages are phagocytes that travel throughout the body in pursuit of invading pathogens.[34] Neutrophils are normally found in the bloodstream and are the most abundant type of phagocyte, representing 50% to 60% of total circulating leukocytes.[35] During the acute phase of inflammation, neutrophils migrate toward the site of inflammation in a process called chemotaxis and are usually the first cells to arrive at the scene of infection. Macrophages are versatile cells that reside within tissues and produce an array of chemicals including enzymes, complement proteins, and cytokines. They can also act as scavengers that rid the body of worn-out cells and other debris and as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that activate the adaptive immune system.[36]

Dendritic cells are phagocytes in tissues that are in contact with the external environment; therefore, they are located mainly in the skin, nose, lungs, stomach, and intestines.[37] They are named for their resemblance to neuronal dendrites, as both have many spine-like projections. Dendritic cells serve as a link between the bodily tissues and the innate and adaptive immune systems, as they present antigens to T cells, one of the key cell types of the adaptive immune system.[37]

Granulocytes are leukocytes that have granules in their cytoplasm. In this category are neutrophils, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. Mast cells reside in connective tissues and mucous membranes and regulate the inflammatory response.[38] They are most often associated with allergy and anaphylaxis.[35] Basophils and eosinophils are related to neutrophils. They secrete chemical mediators that are involved in defending against parasites and play a role in allergic reactions, such as asthma.[39]

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a group of innate immune cells that are derived from common lymphoid progenitor and belong to the lymphoid lineage. These cells are defined by the absence of antigen-specific B- or T-cell receptor (TCR) because of the lack of recombination activating gene. ILCs do not express myeloid or dendritic cell markers.[40]

Natural killer cells (NK cells) are lymphocytes and a component of the innate immune system that does not directly attack invading microbes.[41] Rather, NK cells destroy compromised host cells, such as tumor cells or virus-infected cells, recognizing such cells by a condition known as "missing self". This term describes cells with low levels of a cell-surface marker called MHC I (major histocompatibility complex)—a situation that can arise in viral infections of host cells.[42] Normal body cells are not recognized and attacked by NK cells because they express intact self MHC antigens. Those MHC antigens are recognized by killer cell immunoglobulin receptors, which essentially put the brakes on NK cells.[43]

Inflammation

[edit]Inflammation is one of the first responses of the immune system to infection.[44] The symptoms of inflammation are redness, swelling, heat, and pain, which are caused by increased blood flow into tissue. Inflammation is produced by eicosanoids and cytokines, which are released by injured or infected cells. Eicosanoids include prostaglandins that produce fever and the dilation of blood vessels associated with inflammation and leukotrienes that attract certain white blood cells (leukocytes).[45][46] Common cytokines include interleukins that are responsible for communication between white blood cells; chemokines that promote chemotaxis; and interferons that have antiviral effects, such as shutting down protein synthesis in the host cell.[47] Growth factors and cytotoxic factors may also be released. These cytokines and other chemicals recruit immune cells to the site of infection and promote the healing of any damaged tissue following the removal of pathogens.[48] The pattern-recognition receptors called inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes (consisting of an NLR, the adaptor protein ASC, and the effector molecule pro-caspase-1) that form in response to cytosolic PAMPs and DAMPs, whose function is to generate active forms of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18.[49]

Humoral defenses

[edit]The complement system is a biochemical cascade that attacks the surfaces of foreign cells. It contains over 20 different proteins and is named for its ability to "complement" the killing of pathogens by antibodies. Complement is the major humoral component of the innate immune response.[50][51] Many species have complement systems, including non-mammals like plants, fish, and some invertebrates.[52] In humans, this response is activated by complement binding to antibodies that have attached to these microbes or the binding of complement proteins to carbohydrates on the surfaces of microbes. This recognition signal triggers a rapid killing response.[53] The speed of the response is a result of signal amplification that occurs after sequential proteolytic activation of complement molecules, which are also proteases. After complement proteins initially bind to the microbe, they activate their protease activity, which in turn activates other complement proteases, and so on. This produces a catalytic cascade that amplifies the initial signal by controlled positive feedback.[54] The cascade results in the production of peptides that attract immune cells, increase vascular permeability, and opsonize (coat) the surface of a pathogen, marking it for destruction. This deposition of complement can also kill cells directly by disrupting their plasma membrane via the formation of a membrane attack complex.[50]

Adaptive immune system

[edit]

The adaptive immune system evolved in early vertebrates and allows for a stronger immune response as well as immunological memory, where each pathogen is "remembered" by a signature antigen.[55] The adaptive immune response is antigen-specific and requires the recognition of specific "non-self" antigens during a process called antigen presentation. Antigen specificity allows for the generation of responses that are tailored to specific pathogens or pathogen-infected cells. The ability to mount these tailored responses is maintained in the body by "memory cells". Should a pathogen infect the body more than once, these specific memory cells are used to quickly eliminate it.[56]

Recognition of antigen

[edit]The cells of the adaptive immune system are special types of leukocytes, called lymphocytes. B cells and T cells are the major types of lymphocytes and are derived from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow.[57] B cells are involved in the humoral immune response, whereas T cells are involved in cell-mediated immune response. Killer T cells only recognize antigens coupled to Class I MHC molecules, while helper T cells and regulatory T cells only recognize antigens coupled to Class II MHC molecules. These two mechanisms of antigen presentation reflect the different roles of the two types of T cell. A third, minor subtype are the γδ T cells that recognize intact antigens that are not bound to MHC receptors.[58] The double-positive T cells are exposed to a wide variety of self-antigens in the thymus, in which iodine is necessary for its thymus development and activity.[59] In contrast, the B cell antigen-specific receptor is an antibody molecule on the B cell surface and recognizes native (unprocessed) antigen without any need for antigen processing. Such antigens may be large molecules found on the surfaces of pathogens, but can also be small haptens (such as penicillin) attached to carrier molecule.[60] Each lineage of B cell expresses a different antibody, so the complete set of B cell antigen receptors represent all the antibodies that the body can manufacture.[57] When B or T cells encounter their related antigens they multiply and many "clones" of the cells are produced that target the same antigen. This is called clonal selection.[61]

Antigen presentation to T lymphocytes

[edit]Both B cells and T cells carry receptor molecules that recognize specific targets. T cells recognize a "non-self" target, such as a pathogen, only after antigens (small fragments of the pathogen) have been processed and presented in combination with a "self" receptor called a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule.[62]

Cell mediated immunity

[edit]There are two major subtypes of T cells: the killer T cell and the helper T cell. In addition there are regulatory T cells which have a role in modulating immune response.[63]

Killer T cells

[edit]Killer T cells are a sub-group of T cells that kill cells that are infected with viruses (and other pathogens), or are otherwise damaged or dysfunctional.[64] As with B cells, each type of T cell recognizes a different antigen. Killer T cells are activated when their T-cell receptor binds to this specific antigen in a complex with the MHC Class I receptor of another cell. Recognition of this MHC:antigen complex is aided by a co-receptor on the T cell, called CD8. The T cell then travels throughout the body in search of cells where the MHC I receptors bear this antigen. When an activated T cell contacts such cells, it releases cytotoxins, such as perforin, which form pores in the target cell's plasma membrane, allowing ions, water and toxins to enter. The entry of another toxin called granulysin (a protease) induces the target cell to undergo apoptosis.[65] T cell killing of host cells is particularly important in preventing the replication of viruses. T cell activation is tightly controlled and generally requires a very strong MHC/antigen activation signal, or additional activation signals provided by "helper" T cells (see below).[65]

Helper T cells

[edit]

Helper T cells regulate both the innate and adaptive immune responses and help determine which immune responses the body makes to a particular pathogen.[66][67] These cells have no cytotoxic activity and do not kill infected cells or clear pathogens directly. They instead control the immune response by directing other cells to perform these tasks.[68]

Helper T cells express T cell receptors that recognize antigen bound to Class II MHC molecules. The MHC:antigen complex is also recognized by the helper cell's CD4 co-receptor, which recruits molecules inside the T cell (such as Lck) that are responsible for the T cell's activation. Helper T cells have a weaker association with the MHC:antigen complex than observed for killer T cells, meaning many receptors (around 200–300) on the helper T cell must be bound by an MHC:antigen to activate the helper cell, while killer T cells can be activated by engagement of a single MHC:antigen molecule. Helper T cell activation also requires longer duration of engagement with an antigen-presenting cell.[69] The activation of a resting helper T cell causes it to release cytokines that influence the activity of many cell types. Cytokine signals produced by helper T cells enhance the microbicidal function of macrophages and the activity of killer T cells.[70] In addition, helper T cell activation causes an upregulation of molecules expressed on the T cell's surface, such as CD40 ligand (also called CD154), which provide extra stimulatory signals typically required to activate antibody-producing B cells.[71]

Gamma delta T cells

[edit]Gamma delta T cells (γδ T cells) possess an alternative T-cell receptor (TCR) as opposed to CD4+ and CD8+ (αβ) T cells and share the characteristics of helper T cells, cytotoxic T cells and NK cells. The conditions that produce responses from γδ T cells are not fully understood. Like other 'unconventional' T cell subsets bearing invariant TCRs, such as CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells, γδ T cells straddle the border between innate and adaptive immunity.[72] On one hand, γδ T cells are a component of adaptive immunity as they rearrange TCR genes to produce receptor diversity and can also develop a memory phenotype. On the other hand, the various subsets are also part of the innate immune system, as restricted TCR or NK receptors may be used as pattern recognition receptors. For example, large numbers of human Vγ9/Vδ2 T cells respond within hours to common molecules produced by microbes, and highly restricted Vδ1+ T cells in epithelia respond to stressed epithelial cells.[58]

Humoral immune response

[edit]

A B cell identifies pathogens when antibodies on its surface bind to a specific foreign antigen.[74] This antigen/antibody complex is taken up by the B cell and processed by proteolysis into peptides. The B cell then displays these antigenic peptides on its surface MHC class II molecules. This combination of MHC and antigen attracts a matching helper T cell, which releases lymphokines and activates the B cell.[75] As the activated B cell then begins to divide, its offspring (plasma cells) secrete millions of copies of the antibody that recognizes this antigen. These antibodies circulate in blood plasma and lymph, bind to pathogens expressing the antigen and mark them for destruction by complement activation or for uptake and destruction by phagocytes. Antibodies can also neutralize challenges directly, by binding to bacterial toxins or by interfering with the receptors that viruses and bacteria use to infect cells.[76]

Newborn infants have no prior exposure to microbes and are particularly vulnerable to infection. Several layers of passive protection are provided by the mother. During pregnancy, a particular type of antibody, called IgG, is transported from mother to baby directly through the placenta, so human babies have high levels of antibodies even at birth, with the same range of antigen specificities as their mother.[77] Breast milk or colostrum also contains antibodies that are transferred to the gut of the infant and protect against bacterial infections until the newborn can synthesize its own antibodies.[78] This is passive immunity because the fetus does not actually make any memory cells or antibodies—it only borrows them. This passive immunity is usually short-term, lasting from a few days up to several months. In medicine, protective passive immunity can also be transferred artificially from one individual to another.[79]

Immunological memory

[edit]When B cells and T cells are activated and begin to replicate, some of their offspring become long-lived memory cells. Throughout the lifetime of an animal, these memory cells remember each specific pathogen encountered and can mount a strong response if the pathogen is detected again. T-cells recognize pathogens by small protein-based infection signals, called antigens, that bind directly to T-cell surface receptors.[80] B-cells use the protein, immunoglobulin, to recognize pathogens by their antigens.[81] This is "adaptive" because it occurs during the lifetime of an individual as an adaptation to infection with that pathogen and prepares the immune system for future challenges. Immunological memory can be in the form of either passive short-term memory or active long-term memory.[82]

Physiological regulation

[edit]

The immune system is involved in many aspects of physiological regulation in the body. The immune system interacts intimately with other systems, such as the endocrine[83][84] and the nervous[85][86][87] systems. The immune system also plays a crucial role in embryogenesis (development of the embryo), as well as in tissue repair and regeneration.[88]

Hormones

[edit]Hormones can act as immunomodulators, altering the sensitivity of the immune system. For example, female sex hormones are known immunostimulators of both adaptive[89] and innate immune responses.[90] Some autoimmune diseases such as lupus erythematosus strike women preferentially, and their onset often coincides with puberty. By contrast, male sex hormones such as testosterone seem to be immunosuppressive.[91] Other hormones appear to regulate the immune system as well, most notably prolactin, growth hormone and vitamin D.[92][93]

Vitamin D

[edit]Although early cellular studies suggested vitamin D might influence immune responses, more recent large-scale clinical trials and meta-analyses (2022–2024) have found that vitamin D supplementation can reduce the risk and severity of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, and may modestly reduce the incidence of acute respiratory tract infections and improve tuberculosis outcomes.[94][95][96] A 2011 United States Institute of Medicine report stated that "outcomes related to ... immune functioning and autoimmune disorders, and infections ... could not be linked reliably with calcium or vitamin D intake and were often conflicting."[97]: 5

Sleep and rest

[edit]The immune system is affected by sleep and rest, and sleep deprivation is detrimental to immune function.[98] Complex feedback loops involving cytokines, such as interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α produced in response to infection, appear to also play a role in the regulation of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.[99] Thus the immune response to infection may result in changes to the sleep cycle, including an increase in slow-wave sleep relative to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.[100]

In people with sleep deprivation, active immunizations may have a diminished effect and may result in lower antibody production, and a lower immune response, than would be noted in a well-rested individual.[101][102] Additionally, proteins such as NFIL3, which have been shown to be closely intertwined with both T-cell differentiation and circadian rhythms, can be affected through the disturbance of natural light and dark cycles through instances of sleep deprivation. These disruptions can lead to an increase in chronic conditions such as heart disease, chronic pain, and asthma.[103]

In addition to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation, sleep and the intertwined circadian system have been shown to have strong regulatory effects on immunological functions affecting both innate and adaptive immunity. First, during the early slow-wave-sleep stage, a sudden drop in blood levels of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine causes increased blood levels of the hormones leptin, pituitary growth hormone, and prolactin. These signals induce a pro-inflammatory state through the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1, interleukin-12, TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma. These cytokines then stimulate immune functions such as immune cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation. During this time of a slowly evolving adaptive immune response, there is a peak in undifferentiated or less differentiated cells, like naïve and central memory T cells. In addition to these effects, the milieu of hormones produced at this time (leptin, pituitary growth hormone, and prolactin) supports the interactions between APCs and T-cells, a shift of the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance towards one that supports Th1, an increase in overall Th cell proliferation, and naïve T cell migration to lymph nodes. This is also thought to support the formation of long-lasting immune memory through the initiation of Th1 immune responses.[104]

During wake periods, differentiated effector cells, such as cytotoxic natural killer cells and CD45RA+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, peak in numbers. Anti-inflammatory molecules, such as cortisol and catecholamines, also peak during awake active times. Inflammation can cause oxidative stress and the presence of melatonin during sleep times could counteract free radical production during this time.[104][105]

Physical exercise

[edit]Physical exercise has a positive effect on the immune system and depending on the frequency and intensity, the pathogenic effects of diseases caused by bacteria and viruses are moderated.[106] Immediately after intense exercise there is a transient immunodepression, where the number of circulating lymphocytes decreases and antibody production declines. This may give rise to a window of opportunity for infection and reactivation of latent virus infections,[107] but the evidence is inconclusive.[108][109]

Changes at the cellular level

[edit]

During exercise there is an increase in circulating white blood cells of all types. This is caused by the frictional force of blood flowing on the endothelial cell surface and catecholamines affecting β-adrenergic receptors (βARs).[107] The number of neutrophils in the blood increases and remains raised for up to six hours and immature forms are present. Although the increase in neutrophils ("neutrophilia") is similar to that seen during bacterial infections, after exercise the cell population returns to normal by around 24 hours.[107]

The number of circulating lymphocytes (mainly natural killer cells) decreases during intense exercise but returns to normal after 4 to 6 hours. Although up to 2% of the cells die most migrate from the blood to the tissues, mainly the intestines and lungs, where pathogens are most likely to be encountered.[107]

Some monocytes leave the blood circulation and migrate to the muscles where they differentiate and become macrophages.[107] These cells differentiate into two types: proliferative macrophages, which are responsible for increasing the number of stem cells and restorative macrophages, which are involved their maturing to muscle cells.[110]

Repair and regeneration

[edit]The immune system, particularly the innate component, plays a decisive role in tissue repair after an insult. Key actors include macrophages and neutrophils, but other cellular actors, including γδ T cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), and regulatory T cells (Tregs), are also important. The plasticity of immune cells and the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals are crucial aspects of efficient tissue repair. Immune components and pathways are involved in regeneration as well, for example in amphibians such as in axolotl limb regeneration. According to one hypothesis, organisms that can regenerate (e.g., axolotls) could be less immunocompetent than organisms that cannot regenerate.[111]

Disorders of human immunity

[edit]Failures of host defense occur and fall into three broad categories: immunodeficiencies,[112] autoimmunity,[113] and hypersensitivities.[114]

Immunodeficiencies

[edit]Immunodeficiencies occur when one or more of the components of the immune system are inactive. The ability of the immune system to respond to pathogens is diminished in both the young and the elderly, with immune responses beginning to decline at around 50 years of age due to immunosenescence.[115][116] In developed countries, obesity, alcoholism, and drug use are common causes of poor immune function, while malnutrition is the most common cause of immunodeficiency in developing countries.[116] Diets lacking sufficient protein are associated with impaired cell-mediated immunity, complement activity, phagocyte function, IgA antibody concentrations, and cytokine production. Additionally, the loss of the thymus at an early age through genetic mutation or surgical removal results in severe immunodeficiency and a high susceptibility to infection.[117] Immunodeficiencies can also be inherited or 'acquired'.[118] Severe combined immunodeficiency is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the disturbed development of functional T cells and B cells caused by numerous genetic mutations.[119] Chronic granulomatous disease, where phagocytes have a reduced ability to destroy pathogens, is an example of an inherited, or congenital, immunodeficiency. AIDS and some types of cancer cause acquired immunodeficiency.[120][121]

Autoimmunity

[edit]

Overactive immune responses form the other end of immune dysfunction, particularly the autoimmune diseases. Here, the immune system fails to properly distinguish between self and non-self, and attacks part of the body. Under normal circumstances, many T cells and antibodies react with "self" peptides.[122] One of the functions of specialized cells (located in the thymus and bone marrow) is to present young lymphocytes with self antigens produced throughout the body and to eliminate those cells that recognize self-antigens, preventing autoimmunity.[74] Common autoimmune diseases include Hashimoto's thyroiditis,[123] rheumatoid arthritis,[124] diabetes mellitus type 1,[125] and systemic lupus erythematosus.[126]

Hypersensitivity

[edit]Hypersensitivity is an immune response that damages the body's own tissues. It is divided into four classes (Type I – IV) based on the mechanisms involved and the time course of the hypersensitive reaction. Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate or anaphylactic reaction, often associated with allergy. Symptoms can range from mild discomfort to death. Type I hypersensitivity is mediated by IgE, which triggers degranulation of mast cells and basophils when cross-linked by antigen.[127] Type II hypersensitivity occurs when antibodies bind to antigens on the individual's own cells, marking them for destruction. This is also called antibody-dependent (or cytotoxic) hypersensitivity, and is mediated by IgG and IgM antibodies.[127] Immune complexes (aggregations of antigens, complement proteins, and IgG and IgM antibodies) deposited in various tissues trigger Type III hypersensitivity reactions.[127] Type IV hypersensitivity (also known as cell-mediated or delayed type hypersensitivity) usually takes between two and three days to develop. Type IV reactions are involved in many autoimmune and infectious diseases, but may also involve contact dermatitis. These reactions are mediated by T cells, monocytes, and macrophages.[127]

Idiopathic inflammation

[edit]Inflammation is one of the first responses of the immune system to infection,[44] but it can appear without known cause.

Inflammation is produced by eicosanoids and cytokines, which are released by injured or infected cells. Eicosanoids include prostaglandins that produce fever and the dilation of blood vessels associated with inflammation, and leukotrienes that attract certain white blood cells (leukocytes).[45][46] Common cytokines include interleukins that are responsible for communication between white blood cells; chemokines that promote chemotaxis; and interferons that have anti-viral effects, such as shutting down protein synthesis in the host cell.[47] Growth factors and cytotoxic factors may also be released. These cytokines and other chemicals recruit immune cells to the site of infection and promote healing of any damaged tissue following the removal of pathogens.[48]

Manipulation in medicine

[edit]

The immune response can be manipulated to suppress unwanted responses resulting from autoimmunity, allergy, and transplant rejection, and to stimulate protective responses against pathogens that largely elude the immune system (see immunization) or cancer.[128]

Immunosuppression

[edit]Immunosuppressive drugs are used to control autoimmune disorders or inflammation when excessive tissue damage occurs, and to prevent rejection after an organ transplant.[129][130]

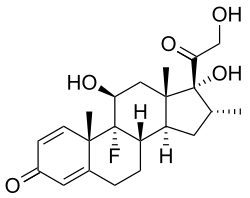

Anti-inflammatory drugs are often used to control the effects of inflammation. Glucocorticoids are the most powerful of these drugs and can have many undesirable side effects, such as central obesity, hyperglycemia, and osteoporosis.[131] Their use is tightly controlled. Lower doses of anti-inflammatory drugs are often used in conjunction with cytotoxic or immunosuppressive drugs such as methotrexate or azathioprine.

Cytotoxic drugs inhibit the immune response by killing dividing cells such as activated T cells. This killing is indiscriminate and other constantly dividing cells and their organs are affected, which causes toxic side effects.[130] Immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporin prevent T cells from responding to signals correctly by inhibiting signal transduction pathways.[132]

Immunostimulation

[edit]Claims made by marketers of various products and alternative health providers, such as chiropractors, homeopaths, and acupuncturists to be able to stimulate or "boost" the immune system generally lack meaningful explanation and evidence of effectiveness.[133]

Vaccination

[edit]

Long-term active memory is acquired following infection by activation of B and T cells. Active immunity can also be generated artificially, through vaccination. The principle behind vaccination (also called immunization) is to introduce an antigen from a pathogen to stimulate the immune system and develop specific immunity against that particular pathogen without causing disease associated with that organism.[134] This deliberate induction of an immune response is successful because it exploits the natural specificity of the immune system, as well as its inducibility. With infectious disease remaining one of the leading causes of death in the human population, vaccination represents the most effective manipulation of the immune system mankind has developed.[57][135]

Many vaccines are based on acellular components of micro-organisms, including harmless toxin components.[134] Since many antigens derived from acellular vaccines do not strongly induce the adaptive response, most bacterial vaccines are provided with additional adjuvants that activate the antigen-presenting cells of the innate immune system and maximize immunogenicity.[136]

Tumor immunology

[edit]Another important role of the immune system is to identify and eliminate tumors. This is called immune surveillance. The transformed cells of tumors express antigens that are not found on normal cells. To the immune system, these antigens appear foreign, and their presence causes immune cells to attack the transformed tumor cells. The antigens expressed by tumors have several sources;[137] some are derived from oncogenic viruses like human papillomavirus, which causes cancer of the cervix,[138] vulva, vagina, penis, anus, mouth, and throat,[139] while others are the organism's own proteins that occur at low levels in normal cells but reach high levels in tumor cells. One example is an enzyme called tyrosinase that, when expressed at high levels, transforms certain skin cells (for example, melanocytes) into tumors called melanomas.[140][141] A third possible source of tumor antigens are proteins normally important for regulating cell growth and survival, that commonly mutate into cancer inducing molecules called oncogenes.[137][142][143]

The main response of the immune system to tumors is to destroy the abnormal cells using killer T cells, sometimes with the assistance of helper T cells.[141][145] Tumor antigens are presented on MHC class I molecules in a similar way to viral antigens. This allows killer T cells to recognize the tumor cell as abnormal.[146] NK cells also kill tumorous cells in a similar way, especially if the tumor cells have fewer MHC class I molecules on their surface than normal; this is a common phenomenon with tumors.[147] Sometimes antibodies are generated against tumor cells allowing for their destruction by the complement system.[142]

Some tumors evade the immune system and go on to become cancers.[148][149] Tumor cells often have a reduced number of MHC class I molecules on their surface, thus avoiding detection by killer T cells.[146][148] Some tumor cells also release products that inhibit the immune response; for example by secreting the cytokine TGF-β, which suppresses the activity of macrophages and lymphocytes.[148][150] In addition, immunological tolerance may develop against tumor antigens, so the immune system no longer attacks the tumor cells.[148][149]

Paradoxically, macrophages can promote tumor growth[151] when tumor cells send out cytokines that attract macrophages, which then generate cytokines and growth factors such as tumor-necrosis factor alpha that nurture tumor development or promote stem-cell-like plasticity.[148] In addition, a combination of hypoxia in the tumor and a cytokine produced by macrophages induces tumor cells to decrease production of a protein that blocks metastasis and thereby assists spread of cancer cells.[148] Anti-tumor M1 macrophages are recruited in early phases to tumor development but are progressively differentiated to M2 with pro-tumor effect, an immunosuppressor switch. The hypoxia reduces the cytokine production for the anti-tumor response and progressively macrophages acquire pro-tumor M2 functions driven by the tumor microenvironment, including IL-4 and IL-10.[152] Cancer immunotherapy covers the medical ways to stimulate the immune system to attack cancer tumors.[153]

Predicting immunogenicity

[edit]Some drugs can cause a neutralizing immune response, meaning that the immune system produces neutralizing antibodies that counteract the action of the drugs, particularly if the drugs are administered repeatedly, or in larger doses. This limits the effectiveness of drugs based on larger peptides and proteins (which are typically larger than 6000 Da).[154] In some cases, the drug itself is not immunogenic, but may be co-administered with an immunogenic compound, as is sometimes the case for Taxol. Computational methods have been developed to predict the immunogenicity of peptides and proteins, which are particularly useful in designing therapeutic antibodies, assessing likely virulence of mutations in viral coat particles, and validation of proposed peptide-based drug treatments. Early techniques relied mainly on the observation that hydrophilic amino acids are overrepresented in epitope regions than hydrophobic amino acids;[155] however, more recent developments rely on machine learning techniques using databases of existing known epitopes, usually on well-studied virus proteins, as a training set.[156] A publicly accessible database has been established for the cataloguing of epitopes from pathogens known to be recognizable by B cells.[157] The emerging field of bioinformatics-based studies of immunogenicity is referred to as immunoinformatics.[158] Immunoproteomics is the study of large sets of proteins (proteomics) involved in the immune response.[159]

Evolution and other mechanisms

[edit]Evolution of the immune system

[edit]It is likely that a multicomponent, adaptive immune system arose with the first vertebrates, as invertebrates do not generate lymphocytes or an antibody-based humoral response.[160] Immune systems evolved in deuterostomes as shown in the cladogram.[160]

Many species, however, use mechanisms that appear to be precursors of these aspects of vertebrate immunity. Immune systems appear even in the structurally simplest forms of life, with bacteria using a unique defense mechanism, called the restriction modification system to protect themselves from viral pathogens, called bacteriophages.[161] Prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) also possess acquired immunity, through a system that uses CRISPR sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of phage that they have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block virus replication through a form of RNA interference.[162][163] Prokaryotes also possess other defense mechanisms.[164][165] Offensive elements of the immune systems are also present in unicellular eukaryotes, but studies of their roles in defense are few.[166]

Pattern recognition receptors are proteins used by nearly all organisms to identify molecules associated with pathogens. Antimicrobial peptides called defensins are an evolutionarily conserved component of the innate immune response found in all animals and plants, and represent the main form of invertebrate systemic immunity.[160] The complement system and phagocytic cells are also used by most forms of invertebrate life. Ribonucleases and the RNA interference pathway are conserved across all eukaryotes, and are thought to play a role in the immune response to viruses.[167]

Unlike animals, plants lack phagocytic cells, but many plant immune responses involve systemic chemical signals that are sent through a plant.[168] Individual plant cells respond to molecules associated with pathogens known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns or PAMPs.[169] When a part of a plant becomes infected, the plant produces a localized hypersensitive response, whereby cells at the site of infection undergo rapid apoptosis to prevent the spread of the disease to other parts of the plant. Systemic acquired resistance is a type of defensive response used by plants that renders the entire plant resistant to a particular infectious agent.[168] RNA silencing mechanisms are particularly important in this systemic response as they can block virus replication.[170]

Alternative adaptive immune system

[edit]Evolution of the adaptive immune system occurred in an ancestor of the jawed vertebrates. Many of the classical molecules of the adaptive immune system (for example, immunoglobulins and T-cell receptors) exist only in jawed vertebrates. A distinct lymphocyte-derived molecule has been discovered in primitive jawless vertebrates, such as the lamprey and hagfish. These animals possess a large array of molecules called Variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) that, like the antigen receptors of jawed vertebrates, are produced from only a small number (one or two) of genes. These molecules are believed to bind pathogenic antigens in a similar way to antibodies, and with the same degree of specificity.[171]

Manipulation by pathogens

[edit]The success of any pathogen depends on its ability to elude host immune responses. Therefore, pathogens evolved several methods that allow them to successfully infect a host, while evading detection or destruction by the immune system.[172] Bacteria often overcome physical barriers by secreting enzymes that digest the barrier, for example, by using a type II secretion system.[173] Alternatively, using a type III secretion system, they may insert a hollow tube into the host cell, providing a direct route for proteins to move from the pathogen to the host. These proteins are often used to shut down host defenses.[174]

An evasion strategy used by several pathogens to avoid the innate immune system is to hide within the cells of their host (also called intracellular pathogenesis). Here, a pathogen spends most of its life-cycle inside host cells, where it is shielded from direct contact with immune cells, antibodies and complement. Some examples of intracellular pathogens include viruses, the food poisoning bacterium Salmonella and the eukaryotic parasites that cause malaria (Plasmodium spp.) and leishmaniasis (Leishmania spp.). Other bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, live inside a protective capsule that prevents lysis by complement.[175] Many pathogens secrete compounds that diminish or misdirect the host's immune response.[172] Some bacteria form biofilms to protect themselves from the cells and proteins of the immune system. Such biofilms are present in many successful infections, such as the chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cenocepacia infections characteristic of cystic fibrosis.[176] Other bacteria generate surface proteins that bind to antibodies, rendering them ineffective; examples include Streptococcus (protein G), Staphylococcus aureus (protein A), and Peptostreptococcus magnus (protein L).[177]

The mechanisms used to evade the adaptive immune system are more complicated. The simplest approach is to rapidly change non-essential epitopes (amino acids and/or sugars) on the surface of the pathogen, while keeping essential epitopes concealed. This is called antigenic variation. An example is HIV, which mutates rapidly, so the proteins on its viral envelope that are essential for entry into its host target cell are constantly changing. These frequent changes in antigens may explain the failures of vaccines directed at this virus.[178] The parasite Trypanosoma brucei uses a similar strategy, constantly switching one type of surface protein for another, allowing it to stay one step ahead of the antibody response.[179] Masking antigens with host molecules is another common strategy for avoiding detection by the immune system. In HIV, the envelope that covers the virion is formed from the outermost membrane of the host cell; such "self-cloaked" viruses make it difficult for the immune system to identify them as "non-self" structures.[180]

History of immunology

[edit]

Immunology is a science that examines the structure and function of the immune system. It originates from medicine and early studies on the causes of immunity to disease. The earliest known reference to immunity was during the plague of Athens in 430 BC. Thucydides noted that people who had recovered from a previous bout of the disease could nurse the sick without contracting the illness a second time.[182] In the 18th century, Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis experimented with scorpion venom and observed that certain dogs and mice were immune to this venom.[183] In the 10th century, Persian physician al-Razi (also known as Rhazes) wrote the first recorded theory of acquired immunity,[184][185] noting that a smallpox bout protected its survivors from future infections. Although he explained the immunity in terms of "excess moisture" being expelled from the blood—therefore preventing a second occurrence of the disease—this theory explained many observations about smallpox known during this time.[186]

These and other observations of acquired immunity were later exploited by Louis Pasteur in his development of vaccination and his proposed germ theory of disease.[187] Pasteur's theory was in direct opposition to contemporary theories of disease, such as the miasma theory. It was not until Robert Koch's 1891 proofs, for which he was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1905, that microorganisms were confirmed as the cause of infectious disease.[188] Viruses were confirmed as human pathogens in 1901, with the discovery of the yellow fever virus by Walter Reed.[189]

Immunology made a great advance towards the end of the 19th century, through rapid developments in the study of humoral immunity and cellular immunity.[190] Particularly important was the work of Paul Ehrlich, who proposed the side-chain theory to explain the specificity of the antigen-antibody reaction; his contributions to the understanding of humoral immunity were recognized by the award of a joint Nobel Prize in 1908, along with the founder of cellular immunology, Elie Metchnikoff.[181] In 1974, Niels Kaj Jerne developed the immune network theory; he shared a Nobel Prize in 1984 with Georges J. F. Köhler and César Milstein for theories related to the immune system.[191][192]

See also

[edit]- Fc receptor

- List of human cell types

- Neuroimmune system

- Original antigenic sin – when the immune system uses immunological memory upon encountering a slightly different pathogen

- Plant disease resistance

- Polyclonal response

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 1.

- ^ a b Litman GW, Cannon JP, Dishaw LJ (November 2005). "Reconstructing immune phylogeny: new perspectives". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 5 (11): 866–79. doi:10.1038/nri1712. PMC 3683834. PMID 16261174.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Restifo NP, Gattinoni L (October 2013). "Lineage relationship of effector and memory T cells". Current Opinion in Immunology. 25 (5): 556–63. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2013.09.003. PMC 3858177. PMID 24148236.

- ^ Kurosaki T, Kometani K, Ise W (March 2015). "Memory B cells". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 15 (3): 149–59. doi:10.1038/nri3802. PMID 25677494. S2CID 20825732.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 11.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 146.

- ^ Alberts et al. 2002, sec. "Pathogens Cross Protective Barriers to Colonize the Host".

- ^ Boyton RJ, Openshaw PJ (2002). "Pulmonary defences to acute respiratory infection". British Medical Bulletin. 61 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1093/bmb/61.1.1. PMID 11997295.

- ^ Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH (2006). "Host antimicrobial defence peptides in human disease". Antimicrobial Peptides and Human Disease. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 306. pp. 67–90. doi:10.1007/3-540-29916-5_3. ISBN 978-3-540-29915-8. PMID 16909918.

- ^ Moreau JM, Girgis DO, Hume EB, Dajcs JJ, Austin MS, O'Callaghan RJ (September 2001). "Phospholipase A(2) in rabbit tears: a host defense against Staphylococcus aureus". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 42 (10): 2347–54. PMID 11527949.

- ^ Hankiewicz J, Swierczek E (December 1974). "Lysozyme in human body fluids". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 57 (3): 205–09. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(74)90398-2. PMID 4434640.

- ^ Fair WR, Couch J, Wehner N (February 1976). "Prostatic antibacterial factor. Identity and significance". Urology. 7 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(76)90305-8. PMID 54972.

- ^ Yenugu S, Hamil KG, Birse CE, Ruben SM, French FS, Hall SH (June 2003). "Antibacterial properties of the sperm-binding proteins and peptides of human epididymis 2 (HE2) family; salt sensitivity, structural dependence and their interaction with outer and cytoplasmic membranes of Escherichia coli". The Biochemical Journal. 372 (Pt 2): 473–83. doi:10.1042/BJ20030225. PMC 1223422. PMID 12628001.

- ^ Smith JL (2003). "The role of gastric acid in preventing foodborne disease and how bacteria overcome acid conditions". J Food Prot. 66 (7): 1292–1303. doi:10.4315/0362-028X-66.7.1292. PMID 12870767.

- ^ Gorbach SL (February 1990). "Lactic acid bacteria and human health". Annals of Medicine. 22 (1): 37–41. doi:10.3109/07853899009147239. PMID 2109988.

- ^ Medzhitov R (October 2007). "Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response". Nature. 449 (7164): 819–26. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..819M. doi:10.1038/nature06246. PMID 17943118. S2CID 4392839.

- ^ Matzinger P (April 2002). "The danger model: a renewed sense of self" (PDF). Science. 296 (5566): 301–05. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..301M. doi:10.1126/science.1071059. PMID 11951032. S2CID 13615808.

- ^ a b Alberts et al. 2002, Chapter: "Innate Immunity".

- ^ Iriti 2019, p. xi.

- ^ Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S (February 2011). "Pathogen recognition by the innate immune system". International Reviews of Immunology. 30 (1): 16–34. doi:10.3109/08830185.2010.529976. PMID 21235323. S2CID 42000671.

- ^ Schroder K, Tschopp J (March 2010). "The inflammasomes". Cell. 140 (6): 821–32. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. PMID 20303873. S2CID 16916572.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Thompson MR, Kaminski JJ, Kurt-Jones EA, Fitzgerald KA (June 2011). "Pattern recognition receptors and the innate immune response to viral infection". Viruses. 3 (6): 920–40. doi:10.3390/v3060920. PMC 3186011. PMID 21994762.

- ^ Beutler B, Jiang Z, Georgel P, Crozat K, Croker B, Rutschmann S, Du X, Hoebe K (2006). "Genetic analysis of host resistance: Toll-like receptor signaling and immunity at large". Annual Review of Immunology. 24: 353–89. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090552. PMID 16551253. S2CID 20991617.

- ^ Botos I, Segal DM, Davies DR (April 2011). "The structural biology of Toll-like receptors". Structure. 19 (4): 447–59. doi:10.1016/j.str.2011.02.004. PMC 3075535. PMID 21481769.

- ^ Vijay K (June 2018). "Toll-like receptors in immunity and inflammatory diseases: Past, present, and future". Int Immunopharmacol. 59: 391–412. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2018.03.002. PMC 7106078. PMID 29730580.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Alberts et al. 2002, sec. "Phagocytic Cells Seek, Engulf, and Destroy Pathogens".

- ^ Ryter A (1985). "Relationship between ultrastructure and specific functions of macrophages". Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 8 (2): 119–33. doi:10.1016/0147-9571(85)90039-6. PMID 3910340.

- ^ Langermans JA, Hazenbos WL, van Furth R (September 1994). "Antimicrobial functions of mononuclear phagocytes". Journal of Immunological Methods. 174 (1–2): 185–94. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(94)90021-3. PMID 8083520.

- ^ May RC, Machesky LM (March 2001). "Phagocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton". Journal of Cell Science. 114 (Pt 6): 1061–77. doi:10.1242/jcs.114.6.1061. PMID 11228151. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Salzet M, Tasiemski A, Cooper E (2006). "Innate immunity in lophotrochozoans: the annelids" (PDF). Current Pharmaceutical Design. 12 (24): 3043–50. doi:10.2174/138161206777947551. PMID 16918433. S2CID 28520695. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2020.

- ^ Zen K, Parkos CA (October 2003). "Leukocyte-epithelial interactions". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 15 (5): 557–64. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00103-0. PMID 14519390.

- ^ a b Stvrtinová, Jakubovský & Hulín 1995, Chapter: Inflammation and Fever.

- ^ Rua R, McGavern DB (September 2015). "Elucidation of monocyte/macrophage dynamics and function by intravital imaging". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 98 (3): 319–32. doi:10.1189/jlb.4RI0115-006RR. PMC 4763596. PMID 26162402.

- ^ a b Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, Théry C, Amigorena S (2002). "Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells". Annual Review of Immunology. 20 (1): 621–67. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064828. PMID 11861614.

- ^ Krishnaswamy, Ajitawi & Chi 2006, pp. 13–34.

- ^ Kariyawasam HH, Robinson DS (April 2006). "The eosinophil: the cell and its weapons, the cytokines, its locations". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 27 (2): 117–27. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939514. PMID 16612762. S2CID 260317790.

- ^ Spits H, Cupedo T (2012). "Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function". Annual Review of Immunology. 30: 647–75. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053. PMID 22224763.

- ^ Gabrielli S, Ortolani C, Del Zotto G, Luchetti F, Canonico B, Buccella F, Artico M, Papa S, Zamai L (2016). "The Memories of NK Cells: Innate-Adaptive Immune Intrinsic Crosstalk". Journal of Immunology Research. 2016 1376595. doi:10.1155/2016/1376595. PMC 5204097. PMID 28078307.

- ^ Bertok & Chow 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Rajalingam 2012, Chapter: Overview of the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor system.

- ^ a b Kawai T, Akira S (February 2006). "Innate immune recognition of viral infection". Nature Immunology. 7 (2): 131–37. doi:10.1038/ni1303. PMID 16424890. S2CID 9567407.

- ^ a b Miller SB (August 2006). "Prostaglandins in health and disease: an overview". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 36 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.03.005. PMID 16887467.

- ^ a b Ogawa Y, Calhoun WJ (October 2006). "The role of leukotrienes in airway inflammation". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 118 (4): 789–98, quiz 799–800. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.009. PMID 17030228.

- ^ a b Le Y, Zhou Y, Iribarren P, Wang J (April 2004). "Chemokines and chemokine receptors: their manifold roles in homeostasis and disease" (PDF). Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 1 (2): 95–104. PMID 16212895.

- ^ a b Martin P, Leibovich SJ (November 2005). "Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly". Trends in Cell Biology. 15 (11): 599–607. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.002. PMID 16202600.

- ^ Platnich JM, Muruve DA (February 2019). "NOD-like receptors and inflammasomes: A review of their canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 670: 4–14. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2019.02.008. PMID 30772258. S2CID 73464235.

- ^ a b Rus H, Cudrici C, Niculescu F (2005). "The role of the complement system in innate immunity". Immunologic Research. 33 (2): 103–12. doi:10.1385/IR:33:2:103. PMID 16234578. S2CID 46096567.

- ^ Degn SE, Thiel S (August 2013). "Humoral pattern recognition and the complement system". Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 78 (2): 181–93. doi:10.1111/sji.12070. PMID 23672641.

- ^ Bertok & Chow 2005, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Liszewski MK, Farries TC, Lublin DM, Rooney IA, Atkinson JP (1996). Control of the Complement System. Advances in Immunology. Vol. 61. pp. 201–283. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60868-8. ISBN 978-0-12-022461-6. PMID 8834497.

- ^ Sim RB, Tsiftsoglou SA (February 2004). "Proteases of the complement system" (PDF). Biochemical Society Transactions. 32 (Pt 1): 21–27. doi:10.1042/BST0320021. PMID 14748705. S2CID 24505041. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2019.

- ^ Pancer Z, Cooper MD (2006). "The evolution of adaptive immunity". Annual Review of Immunology. 24 (1): 497–518. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090542. PMID 16551257.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Janeway 2005.

- ^ a b Holtmeier W, Kabelitz D (2005). "gammadelta T cells link innate and adaptive immune responses". Chemical Immunology and Allergy. 86: 151–83. doi:10.1159/000086659. ISBN 3-8055-7862-8. PMID 15976493.

- ^ Venturi S, Venturi M (September 2009). "Iodine, thymus, and immunity". Nutrition. 25 (9): 977–79. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2009.06.002. PMID 19647627.

- ^ Janeway, Travers & Walport 2001, sec. 12-10.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Harty JT, Tvinnereim AR, White DW (2000). "CD8+ T cell effector mechanisms in resistance to infection". Annual Review of Immunology. 18 (1): 275–308. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.275. PMID 10837060.

- ^ a b Radoja S, Frey AB, Vukmanovic S (2006). "T-cell receptor signaling events triggering granule exocytosis". Critical Reviews in Immunology. 26 (3): 265–90. doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v26.i3.40. PMID 16928189.

- ^ Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A (October 1996). "Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes". Nature. 383 (6603): 787–93. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..787A. doi:10.1038/383787a0. PMID 8893001. S2CID 4319699.

- ^ McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Malherbe LP, McHeyzer-Williams MG (2006). "Helper T cell-regulated B cell immunity". From Innate Immunity to Immunological Memory. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 311. pp. 59–83. doi:10.1007/3-540-32636-7_3. ISBN 978-3-540-32635-9. PMID 17048705.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 8.

- ^ Kovacs B, Maus MV, Riley JL, Derimanov GS, Koretzky GA, June CH, Finkel TH (November 2002). "Human CD8+ T cells do not require the polarization of lipid rafts for activation and proliferation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (23): 15006–11. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9915006K. doi:10.1073/pnas.232058599. PMC 137535. PMID 12419850.

- ^ Alberts et al. 2002, Chapter. "Helper T Cells and Lymphocyte Activation".

- ^ Grewal IS, Flavell RA (1998). "CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity". Annual Review of Immunology. 16 (1): 111–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. PMID 9597126.

- ^ Girardi M (January 2006). "Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by gammadelta T cells". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 126 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. PMID 16417214.

- ^ "Understanding the Immune System: How it Works" (PDF). National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ a b Sproul TW, Cheng PC, Dykstra ML, Pierce SK (2000). "A role for MHC class II antigen processing in B cell development". International Reviews of Immunology. 19 (2–3): 139–55. doi:10.3109/08830180009088502. PMID 10763706. S2CID 6550357.

- ^ Parker DC (1993). "T cell-dependent B cell activation". Annual Review of Immunology. 11: 331–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001555. PMID 8476565.

- ^ Murphy & Weaver 2016, Chapter 10: The Humoral Immune Response.

- ^ Saji F, Samejima Y, Kamiura S, Koyama M (May 1999). "Dynamics of immunoglobulins at the feto-maternal interface" (PDF). Reviews of Reproduction. 4 (2): 81–89. doi:10.1530/ror.0.0040081. PMID 10357095. S2CID 31099552. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2021.

- ^ Van de Perre P (July 2003). "Transfer of antibody via mother's milk". Vaccine. 21 (24): 3374–76. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00336-0. PMID 12850343.

- ^ Keller MA, Stiehm ER (October 2000). "Passive immunity in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 13 (4): 602–14. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.4.602-614.2000. PMC 88952. PMID 11023960.

- ^ Sauls RS, McCausland C, Taylor BN. Histology, T-Cell Lymphocyte. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535433/

- ^ Althwaiqeb SA, Bordoni B. Histology, B Cell Lymphocyte. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560905/

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, p. 98.

- ^ Wick G, Hu Y, Schwarz S, Kroemer G (October 1993). "Immunoendocrine communication via the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in autoimmune diseases". Endocrine Reviews. 14 (5): 539–63. doi:10.1210/edrv-14-5-539. PMID 8262005.

- ^ Kroemer G, Brezinschek HP, Faessler R, Schauenstein K, Wick G (June 1988). "Physiology and pathology of an immunoendocrine feedback loop". Immunology Today. 9 (6): 163–5. doi:10.1016/0167-5699(88)91289-3. PMID 3256322.

- ^ Trakhtenberg EF, Goldberg JL (October 2011). "Immunology. Neuroimmune communication". Science. 334 (6052): 47–8. Bibcode:2011Sci...334...47T. doi:10.1126/science.1213099. PMID 21980100. S2CID 36504684.

- ^ Veiga-Fernandes H, Mucida D (May 2016). "Neuro-Immune Interactions at Barrier Surfaces". Cell. 165 (4): 801–11. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.041. PMC 4871617. PMID 27153494.

- ^ "Neuroimmune communication". Nature Neuroscience. 20 (2): 127. February 2017. doi:10.1038/nn.4496. PMID 28092662.

- ^ Wilcox SM, Arora H, Munro L, Xin J, Fenninger F, Johnson LA, Pfeifer CG, Choi KB, Hou J, Hoodless PA, Jefferies WA (2017). "The role of the innate immune response regulatory gene ABCF1 in mammalian embryogenesis and development". PLOS ONE. 12 (5) e0175918. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1275918W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175918. PMC 5438103. PMID 28542262.

- ^ Wira, Crane-Godreau & Grant 2004, Chapter: Endocrine regulation of the mucosal immune system in the female reproductive tract.

- ^ Lang TJ (December 2004). "Estrogen as an immunomodulator". Clinical Immunology. 113 (3): 224–30. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2004.05.011. PMID 15507385.

Moriyama A, Shimoya K, Ogata I, Kimura T, Nakamura T, Wada H, Ohashi K, Azuma C, Saji F, Murata Y (July 1999). "Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) concentrations in cervical mucus of women with normal menstrual cycle". Molecular Human Reproduction. 5 (7): 656–61. doi:10.1093/molehr/5.7.656. PMID 10381821.

Cutolo M, Sulli A, Capellino S, Villaggio B, Montagna P, Seriolo B, Straub RH (2004). "Sex hormones influence on the immune system: basic and clinical aspects in autoimmunity". Lupus. 13 (9): 635–38. doi:10.1191/0961203304lu1094oa. PMID 15485092. S2CID 23941507.

King AE, Critchley HO, Kelly RW (February 2000). "Presence of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor in human endometrium and first trimester decidua suggests an antibacterial protective role". Molecular Human Reproduction. 6 (2): 191–96. doi:10.1093/molehr/6.2.191. PMID 10655462. - ^ Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC (2005). "Influence of physiological androgen levels on wound healing and immune status in men". The Aging Male. 8 (3–4): 166–74. doi:10.1080/13685530500233847. PMID 16390741. S2CID 1021367.

- ^ Dorshkind K, Horseman ND (June 2000). "The roles of prolactin, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I, and thyroid hormones in lymphocyte development and function: insights from genetic models of hormone and hormone receptor deficiency". Endocrine Reviews. 21 (3): 292–312. doi:10.1210/edrv.21.3.0397. PMID 10857555.

- ^ Nagpal S, Na S, Rathnachalam R (August 2005). "Noncalcemic actions of vitamin D receptor ligands". Endocrine Reviews. 26 (5): 662–87. doi:10.1210/er.2004-0002. PMID 15798098.

- ^ Mercier, F. (April 2024). "Effect of vitamin D on inflammatory and clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews.

- ^ Li, Y. (February 2024). "Vitamin D3 as an add-on treatment for multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders.

- ^ "Efficacy and safety of vitamin D in tuberculosis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. July 2022.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2011). "8, Implications and Special Concerns". In Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by the National Institutes of Health. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/13050. ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. PMID 21796828. S2CID 58721779.

- ^ Bryant PA, Trinder J, Curtis N (June 2004). "Sick and tired: Does sleep have a vital role in the immune system?". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 4 (6): 457–67. doi:10.1038/nri1369. PMID 15173834. S2CID 29318345.

- ^ Krueger JM, Majde JA (May 2003). "Humoral links between sleep and the immune system: research issues". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 992 (1): 9–20. Bibcode:2003NYASA.992....9K. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03133.x. PMID 12794042. S2CID 24508121.

- ^ Majde JA, Krueger JM (December 2005). "Links between the innate immune system and sleep". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 116 (6): 1188–98. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.005. PMID 16337444.

- ^ Taylor DJ, Kelly K, Kohut ML, Song KS (2017). "Is Insomnia a Risk Factor for Decreased Influenza Vaccine Response?". Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 15 (4): 270–287. doi:10.1080/15402002.2015.1126596. PMC 5554442. PMID 27077395.

- ^ Rayatdoost, Esmail; Rahmanian, Mohammad; Sanie, Mohammad Sadegh; Rahmanian, Jila; Matin, Sara; Kalani, Navid; Kenarkoohi, Azra; Falahi, Shahab; Abdoli, Amir (June 2022). "Sufficient Sleep, Time of Vaccination, and Vaccine Efficacy: A Systematic Review of the Current Evidence and a Proposal for COVID-19 Vaccination". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 95 (2): 221–235. ISSN 1551-4056. PMC 9235253. PMID 35782481.

- ^ Krueger JM (2008). "The role of cytokines in sleep regulation". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 14 (32): 3408–16. doi:10.2174/138161208786549281. PMC 2692603. PMID 19075717.

- ^ a b Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J (January 2012). "Sleep and immune function". Pflügers Archiv. 463 (1): 121–37. doi:10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0. PMC 3256323. PMID 22071480.

- ^ "Can Better Sleep Mean Catching fewer Colds?". Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ da Silveira MP, da Silva Fagundes KK, Bizuti MR, Starck É, Rossi RC, de Resende E, Silva DT (February 2021). "Physical exercise as a tool to help the immune system against COVID-19: an integrative review of the current literature". Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 21 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1007/s10238-020-00650-3. PMC 7387807. PMID 32728975.

- ^ a b c d e Peake JM, Neubauer O, Walsh NP, Simpson RJ (May 2017). "Recovery of the immune system after exercise" (PDF). Journal of Applied Physiology. 122 (5): 1077–1087. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00622.2016. PMID 27909225. S2CID 3521624.

- ^ Campbell JP, Turner JE (2018). "Debunking the Myth of Exercise-Induced Immune Suppression: Redefining the Impact of Exercise on Immunological Health Across the Lifespan". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 648. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00648. PMC 5911985. PMID 29713319.

- ^ Simpson RJ, Campbell JP, Gleeson M, Krüger K, Nieman DC, Pyne DB, Turner JE, Walsh NP (2020). "Can exercise affect immune function to increase susceptibility to infection?". Exercise Immunology Review. 26: 8–22. PMID 32139352.

- ^ Minari AL, Thomatieli-Santos RV (January 2022). "From skeletal muscle damage and regeneration to the hypertrophy induced by exercise: what is the role of different macrophage subsets?". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 322 (1): R41 – R54. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00038.2021. PMID 34786967. S2CID 244369441.

- ^ Godwin JW, Pinto AR, Rosenthal NA (January 2017). "Chasing the recipe for a pro-regenerative immune system". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. Innate immune pathways in wound healing/Peromyscus as a model system. 61: 71–79. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.08.008. PMC 5338634. PMID 27521522.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 120–24.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 114–18.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 111–14.

- ^ Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB (April 2007). "Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population". Immunology. 120 (4): 435–46. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02555.x. PMC 2265901. PMID 17313487.

- ^ a b Chandra RK (August 1997). "Nutrition and the immune system: an introduction". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 66 (2): 460S – 63S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/66.2.460S. PMID 9250133.

- ^ Miller JF (July 2002). "The discovery of thymus function and of thymus-derived lymphocytes". Immunological Reviews. 185 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.18502.x. PMID 12190917. S2CID 12108587.

- ^ Reece 2011, p. 967.

- ^ Burg M, Gennery AR (2011). "Educational paper: The expanding clinical and immunological spectrum of severe combined immunodeficiency". Eur J Pediatr. 170 (5): 561–571. doi:10.1007/s00431-011-1452-3. PMC 3078321. PMID 21479529.

- ^ Joos L, Tamm M (2005). "Breakdown of pulmonary host defense in the immunocompromised host: cancer chemotherapy". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2 (5): 445–48. doi:10.1513/pats.200508-097JS. PMID 16322598.

- ^ Copeland KF, Heeney JL (December 1996). "T helper cell activation and human retroviral pathogenesis". Microbiological Reviews. 60 (4): 722–42. doi:10.1128/MMBR.60.4.722-742.1996. PMC 239461. PMID 8987361.

- ^ Miller JF (1993). "Self-nonself discrimination and tolerance in T and B lymphocytes". Immunologic Research. 12 (2): 115–30. doi:10.1007/BF02918299. PMID 8254222. S2CID 32476323.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Hashimoto's disease". Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 12 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Hashimoto's disease". Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 12 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB (October 2016). "Rheumatoid arthritis" (PDF). Lancet. 388 (10055): 2023–2038. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8. PMID 27156434. S2CID 37973054.

- ^ Farhy LS, McCall AL (July 2015). "Glucagon - the new 'insulin' in the pathophysiology of diabetes". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 18 (4): 407–14. doi:10.1097/mco.0000000000000192. PMID 26049639. S2CID 19872862.

- ^ "Handout on Health: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus". www.niams.nih.gov. February 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d Ghaffar A (2006). "Immunology – Chapter Seventeen: Hypersensitivity States". Microbiology and Immunology On-line. University of South Carolina School of Medicine. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ Sompayrac 2019, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Ciccone 2015, Chapter 37.

- ^ a b Taylor AL, Watson CJ, Bradley JA (October 2005). "Immunosuppressive agents in solid organ transplantation: Mechanisms of action and therapeutic efficacy". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 56 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.03.012. PMID 16039869.

- ^ Barnes PJ (March 2006). "Corticosteroids: the drugs to beat". European Journal of Pharmacology. 533 (1–3): 2–14. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.052. PMID 16436275.

- ^ Masri MA (July 2003). "The mosaic of immunosuppressive drugs". Molecular Immunology. 39 (17–18): 1073–77. doi:10.1016/S0161-5890(03)00075-0. PMID 12835079.

- ^ Hall H (July–August 2020). "How You Can Really Boost Your Immune System". Skeptical Inquirer. Amherst, New York: Center for Inquiry. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ a b Reece 2011, p. 965.

- ^ Death and DALY estimates for 2002 by cause for WHO Member States. Archived 21 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine World Health Organization. Retrieved on 1 January 2007.

- ^ Singh M, O'Hagan D (November 1999). "Advances in vaccine adjuvants". Nature Biotechnology. 17 (11): 1075–81. doi:10.1038/15058. PMID 10545912. S2CID 21346647.

- ^ a b Andersen MH, Schrama D, Thor Straten P, Becker JC (January 2006). "Cytotoxic T cells". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 126 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700001. PMID 16417215.

- ^ Boon T, van der Bruggen P (March 1996). "Human tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 183 (3): 725–29. doi:10.1084/jem.183.3.725. PMC 2192342. PMID 8642276.

- ^ Ljubojevic S, Skerlev M (2014). "HPV-associated diseases". Clinics in Dermatology. 32 (2): 227–34. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.08.007. PMID 24559558.