Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Overexploitation

View on WikipediaThis article may incorporate text from a large language model. (August 2025) |

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting or ecological overshoot, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns.[2] Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term applies to natural resources such as water aquifers, grazing pastures and forests, wild medicinal plants, fish stocks and other wildlife.

In ecology, overexploitation describes one of the five main activities threatening global biodiversity.[3] Ecologists use the term to describe populations that are harvested at an unsustainable rate, given their natural rates of mortality and capacities for reproduction. This can result in extinction at the population level and even extinction of whole species. In conservation biology, the term is usually used in the context of human economic activity that involves the taking of biological resources, or organisms, in larger numbers than their populations can withstand.[4] The term is also used and defined somewhat differently in fisheries, hydrology and natural resource management.

Overexploitation can lead to resource destruction, including extinctions. However, it is also possible for overexploitation to be sustainable, as discussed below in the section on fisheries. In the context of fishing, the term overfishing can be used instead of overexploitation, as can overgrazing in stock management, overlogging in forest management, overdrafting in aquifer management, and endangered species in species monitoring. Overexploitation is not an activity limited to humans. Introduced predators and herbivores, for example, can overexploit native flora and fauna.

History

[edit]

The concern about overexploitation, while relatively recent in the annals of modern environmental awareness, traces back to ancient practices embedded in human history. Contrary to the notion that overexploitation is an exclusively contemporary issue, the phenomenon has been documented for millennia and is not limited to human activities alone. Historical evidence reveals that various cultures and societies have engaged in practices leading to the overuse of natural resources, sometimes with drastic consequences.

One poignant example can be found in the ceremonial cloaks of Hawaiian kings, which were adorned with the feathers of the now-extinct mamo bird. Crafting a single cloak required the feathers of approximately 70,000 adult mamo birds, illustrating a staggering scale of resource extraction that ultimately contributed to its extinction. This instance underscores how cultural traditions and their associated demands can sometimes precipitate the overexploitation of a species to the brink of extinction.[7][8]

Similarly, the story of the dodo bird from Mauritius provides another clear example of overexploitation. The dodo, a flightless bird, exhibited a lack of fear toward predators, including humans, making it exceptionally vulnerable to hunting. The dodo's naivety and the absence of natural defenses against human hunters and introduced species led to its rapid extinction. This case offers insight into how certain species, particularly those isolated on islands, can be disproportionately affected by human activities due to their evolutionary adaptations.[9]

Hunting has long been a vital human activity for survival, providing food, clothing, and tools. However, the history of hunting also includes episodes of overexploitation, particularly in the form of overhunting. The overkill hypothesis, which addresses the Quaternary extinction events, explains the relatively rapid extinction of megafauna. This hypothesis suggests that these extinctions were closely linked to human migration and population growth. One of the most compelling pieces of evidence supporting this theory is that approximately 80% of North American large mammal species disappeared within just approximately a thousand years of humans arriving in the Western Hemisphere. This rapid disappearance indicates a significant impact of human activity on these species, underscoring the profound influence humans have had on their environment throughout history.[10]

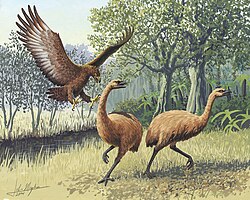

The fastest-ever recorded extinction of megafauna occurred in New Zealand. By 1500 AD, a mere 200 years after the first human settlements, ten species of the giant moa birds were driven to extinction by the Māori. This rapid extinction underscores the significant impact humans can have on native wildlife, especially in isolated ecosystems like New Zealand. The Māori, relying on the moa as a primary food source and for resources such as feathers and bones, hunted these birds extensively. The moa's inability to fly and their size, which made them easier targets, contributed to their rapid decline. This event serves as a cautionary tale about the delicate balance between human activity and biodiversity and highlights the potential consequences of over-hunting and habitat destruction.[5] A second wave of extinctions occurred later with European settlement. This period marked significant ecological disruption, largely due to the introduction of new species and land-use changes. European settlers brought with them animals such as rats, cats, and stoats, which preyed upon native birds and other wildlife. Additionally, deforestation for agriculture significantly altered the habitats of many endemic species. These combined factors accelerated the decline of New Zealand's unique biodiversity, leading to the extinction of several more species. The European settlement period serves as a poignant example of how human activities can drastically impact natural ecosystems.

In more recent times, overexploitation has resulted in the gradual emergence of the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development, which has built on other concepts, such as sustainable yield,[11] eco-development,[12][13] and deep ecology.[14][15]

Overview

[edit]Overexploitation does not necessarily lead to the destruction of the resource, nor is it necessarily unsustainable. However, depleting the numbers or amount of the resource can change its quality. For example, footstool palm is a wild palm tree found in Southeast Asia. Its leaves are used for thatching and food wrapping, and overharvesting has resulted in its leaf size becoming smaller.

Tragedy of the commons

[edit]

In 1968, the journal Science published an article by Garrett Hardin entitled "The Tragedy of the Commons".[16] It was based on a parable that William Forster Lloyd published in 1833 to explain how individuals innocently acting in their own self-interest can overexploit, and destroy, a resource that they all share.[17][pages needed] Lloyd described a simplified hypothetical situation based on medieval land tenure in Europe. Herders share common land on which they are each entitled to graze their cows. In Hardin's article, it is in each herder's individual interest to graze each new cow that the herder acquires on the common land, even if the carrying capacity of the common is exceeded, which damages the common for all the herders. The self-interested herder receives all of the benefits of having the additional cow, while all the herders share the damage to the common. However, all herders reach the same rational decision to buy additional cows and graze them on the common, which eventually destroys the common. Hardin concludes:

Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.[16]: 1244

In the course of his essay, Hardin develops the theme, drawing in many examples of latter day commons, such as national parks, the atmosphere, oceans, rivers and fish stocks. The example of fish stocks had led some to call this the "tragedy of the fishers".[18] A major theme running through the essay is the growth of human populations, with the Earth's finite resources being the general common.

The tragedy of the commons has intellectual roots tracing back to Aristotle, who noted that "what is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it",[19] as well as to Hobbes and his Leviathan.[20] The opposite situation to a tragedy of the commons is sometimes referred to as a tragedy of the anticommons: a situation in which rational individuals, acting separately, collectively waste a given resource by underutilizing it.

The tragedy of the commons can be avoided if it is appropriately regulated. Hardin's use of "commons" has frequently been misunderstood, leading Hardin to later remark that he should have titled his work "The tragedy of the unregulated commons".[21]

Sectors

[edit]Fisheries

[edit]

In wild fisheries, overexploitation or overfishing occurs when a fish stock has been fished down "below the size that, on average, would support the long-term maximum sustainable yield of the fishery".[22]

When a fishery starts harvesting fish from a previously unexploited stock, the biomass of the fish stock will decrease, since harvesting means fish are being removed. For sustainability, the rate at which the fish replenish biomass through reproduction must balance the rate at which the fish are being harvested. If the harvest rate is increased, then the stock biomass will further decrease. At a certain point, the maximum harvest yield that can be sustained will be reached, and further attempts to increase the harvest rate will result in the collapse of the fishery. This point is called the maximum sustainable yield, and in practice, usually occurs when the fishery has been fished down to about 30% of the biomass it had before harvesting started.[23]

Fish stocks are said to "collapse" if their biomass declines by more than 95 percent of their maximum historical biomass. Atlantic cod stocks were severely overexploited in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to their abrupt collapse in 1992.[1] Even though fishing has ceased, the cod stocks have failed to recover.[1] The absence of cod as the apex predator in many areas has led to trophic cascades.[1]

About 25% of world fisheries are now overexploited to the point where their current biomass is less than the level that maximizes their sustainable yield.[24] These depleted fisheries can often recover if fishing pressure is reduced until the stock biomass returns to the optimal biomass. At this point, harvesting can be resumed near the maximum sustainable yield.[25]

The tragedy of the commons can be avoided within the context of fisheries if fishing effort and practices are regulated appropriately by fisheries management. One effective approach may be assigning some measure of ownership in the form of individual transferable quotas (ITQs) to fishermen. In 2008, a large scale study of fisheries that used ITQs, and ones that did not, provided strong evidence that ITQs help prevent collapses and restore fisheries that appear to be in decline.[26][27]

Water resources

[edit]Water resources, such as lakes and aquifers, are usually renewable resources which naturally recharge (the term fossil water is sometimes used to describe aquifers which do not recharge). Overexploitation occurs if a water resource, such as the Ogallala Aquifer, is mined or extracted at a rate that exceeds the recharge rate, that is, at a rate that exceeds the practical sustained yield. Recharge usually comes from area streams, rivers and lakes. An aquifer which has been overexploited is said to be overdrafted or depleted. Forests enhance the recharge of aquifers in some locales, although generally forests are a major source of aquifer depletion.[28][29] Depleted aquifers can become polluted with contaminants such as nitrates, or permanently damaged through subsidence or through saline intrusion from the ocean.

This turns much of the world's underground water and lakes into finite resources with peak usage debates similar to oil.[30][31] These debates usually centre around agriculture and suburban water usage but generation of electricity from nuclear energy or coal and tar sands mining is also water resource intensive.[32] A modified Hubbert curve applies to any resource that can be harvested faster than it can be replaced.[33] Though Hubbert's original analysis did not apply to renewable resources, their overexploitation can result in a Hubbert-like peak. This has led to the concept of peak water.

Forestry

[edit]

Forests are overexploited when they are logged at a rate faster than reforestation takes place. Reforestation competes with other land uses such as food production, livestock grazing, and living space for further economic growth. Historically utilization of forest products, including timber and fuel wood, have played a key role in human societies, comparable to the roles of water and cultivable land. Today, developed countries continue to utilize timber for building houses, and wood pulp for paper. In developing countries almost three billion people rely on wood for heating and cooking.[34] Short-term economic gains made by conversion of forest to agriculture, or overexploitation of wood products, typically leads to loss of long-term income and long term biological productivity. West Africa, Madagascar, Southeast Asia and many other regions have experienced lower revenue because of overexploitation and the consequent declining timber harvests.[35]

Biodiversity

[edit]

Overexploitation is one of the main threats to global biodiversity.[3] Other threats include pollution, introduced and invasive species, habitat fragmentation, habitat destruction,[3] uncontrolled hybridization,[36] climate change,[37] ocean acidification[38] and the driver behind many of these, human overpopulation.[39]

One of the key health issues associated with biodiversity is drug discovery and the availability of medicinal resources.[40] A significant proportion of drugs are natural products derived, directly or indirectly, from biological sources. Marine ecosystems are of particular interest in this regard.[41] However, unregulated and inappropriate bioprospecting could potentially lead to overexploitation, ecosystem degradation and loss of biodiversity.[42][43][44]

Endangered and extinct species

[edit]

Species from all groups of fauna and flora are affected by overexploitation. This phenomenon is not bound by taxonomy; it spans across mammals, birds, fish, insects, and plants alike. Animals are hunted for their fur, tusks, or meat, while plants are harvested for medicinal purposes, timber, or ornamental uses. This unsustainable practice disrupts ecosystems, threatening biodiversity and leading to the potential extinction of vulnerable species.

All living organisms require resources to survive. Overexploitation of these resources for protracted periods can deplete natural stocks to the point where they are unable to recover within a short time frame. Humans have always harvested food and other resources they need to survive. Human populations, historically, were small, and methods of collection were limited to small quantities. With an exponential increase in human population, expanding markets and increasing demand, combined with improved access and techniques for capture, are causing the exploitation of many species beyond sustainable levels.[45] In practical terms, if continued, it reduces valuable resources to such low levels that their exploitation is no longer sustainable and can lead to the extinction of a species, in addition to having dramatic, unforeseen effects, on the ecosystem.[46] Overexploitation often occurs rapidly as markets open, utilising previously untapped resources, or locally used species.

Today, overexploitation and misuse of natural resources is an ever-present threat for species richness. This is more prevalent when looking at island ecology and the species that inhabit them, as islands can be viewed as the world in miniature. Island endemic populations are more prone to extinction from overexploitation, as they often exist at low densities with reduced reproductive rates.[47] A good example of this are island snails, such as the Hawaiian Achatinella and the French Polynesian Partula. Achatinelline snails have 15 species listed as extinct and 24 critically endangered[48] while 60 species of partulidae are considered extinct with 14 listed as critically endangered.[49] The WCMC have attributed over-collecting and very low lifetime fecundity for the extreme vulnerability exhibited among these species.[50]

As another example, when the humble hedgehog was introduced to the Scottish island of Uist, the population greatly expanded and took to consuming and overexploiting shorebird eggs, with drastic consequences for their breeding success. Twelve species of avifauna are affected, with some species numbers being reduced by 39%.[51]

Where there is substantial human migration, civil unrest, or war, controls may no longer exist. With civil unrest, for example in the Congo and Rwanda, firearms have become common and the breakdown of food distribution networks in such countries leaves the resources of the natural environment vulnerable.[52] Animals are even killed as target practice, or simply to spite the government. Populations of large primates, such as gorillas and chimpanzees, ungulates and other mammals, may be reduced by 80% or more by hunting, and certain species may be eliminated.[53] This decline has been called the bushmeat crisis.

Vertebrates

[edit]Overexploitation threatens one-third of endangered vertebrates, as well as other groups. Excluding edible fish, the illegal trade in wildlife is valued at $10 billion per year. Industries responsible for this include the trade in bushmeat, the trade in Chinese medicine, and the fur trade.[54] The Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or CITES was set up in order to control and regulate the trade in endangered animals. It currently protects, to a varying degree, some 33,000 species of animals and plants. It is estimated that a quarter of the endangered vertebrates in the United States of America and half of the endangered mammals is attributed to overexploitation.[3][55]

Birds

[edit]Overall, 50 bird species that have become extinct since 1500 (approximately 40% of the total) have been subject to overexploitation,[56] including:

- Great Auk – the penguin-like bird of the north, was hunted for its feathers, meat, fat and oil.

- Carolina parakeet – The only parrot species native to the eastern United States, was hunted for crop protection and its feathers.

Mammals

[edit]- The international trade in fur: chinchilla, vicuña, giant otter and numerous cat species

Fish

[edit]Various

[edit]- Novelty pets: snakes, parrots, primates and big cats[57]

- Chinese medicine: bears, tigers, rhinos, seahorses, Asian black bear and saiga antelope[58]

Invertebrates

[edit]Plants

[edit]- Horticulturists: New Zealand mistletoe (Trilepidea adamsii), orchids, cacti and many other plant species

Cascade effects

[edit]

Overexploitation of species can result in knock-on or cascade effects. This can particularly apply if, through overexploitation, a habitat loses its apex predator. Because of the loss of the top predator, a dramatic increase in their prey species can occur. In turn, the unchecked prey can then overexploit their own food resources until population numbers dwindle, possibly to the point of extinction.

A classic example of cascade effects occurred with sea otters. Starting before the 17th century and not phased out until 1911, sea otters were hunted aggressively for their exceptionally warm and valuable pelts, which could fetch up to $2500 US. This caused cascade effects through the kelp forest ecosystems along the Pacific Coast of North America.[59]

One of the sea otters' primary food sources is the sea urchin. When hunters caused sea otter populations to decline, an ecological release of sea urchin populations occurred. The sea urchins then overexploited their main food source, kelp, creating urchin barrens, areas of seabed denuded of kelp, but carpeted with urchins. No longer having food to eat, the sea urchin became locally extinct as well. Also, since kelp forest ecosystems are homes to many other species, the loss of the kelp caused other cascade effects of secondary extinctions.[60]

In 1911, when only one small group of 32 sea otters survived in a remote cove, an international treaty was signed to prevent further exploitation of the sea otters. Under heavy protection, the otters multiplied and repopulated the depleted areas, which slowly recovered. More recently, with declining numbers of fish stocks, again due to overexploitation, killer whales have experienced a food shortage and have been observed feeding on sea otters, again reducing their numbers.[61]

See also

[edit]- Carrying capacity

- Common-pool resource

- Conservation biology

- Defaunation

- Deforestation

- Ecological footprint

- Ecological overshoot

- Ecosystem management

- Earth Overshoot Day

- Exploitation of natural resources

- Extinction

- Human overpopulation

- Inverse commons

- Over-consumption

- Overpopulation in wild animals

- Paradox of enrichment

- Planetary boundaries

- Social dilemma

- Sustainability

- Tyranny of small decisions

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Frank, Kenneth T.; Petrie, Brian; Choi, Jae S.; Leggett, William C. (2005). "Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem". Science. 308 (5728): 1621–1623. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1621F. doi:10.1126/science.1113075. PMID 15947186. S2CID 45088691.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; Ehrlich, Anne H. (1972). Population, Resources, Environment: Issues in Human Ecology (2nd ed.). W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 127. ISBN 0-7167-0695-4.

- ^ a b c d Wilcove, D. S.; Rothstein, D.; Dubow, J.; Phillips, A.; Losos, E. (1998). "Quantifying threats to imperiled species in the United States". BioScience. 48 (8): 607–615. doi:10.2307/1313420. JSTOR 1313420.

- ^ Oxford. (1996). Oxford Dictionary of Biology. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Holdaway, R. N.; Jacomb, C. (2000). "Rapid Extinction of the Moas (Aves: Dinornithiformes): Model, Test, and Implications" (PDF). Science. 287 (5461): 2250–2254. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.2250H. doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2250. PMID 10731144. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-27.

- ^ Tennyson, A.; Martinson, P. (2006). Extinct Birds of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Papa Press. ISBN 978-0-909010-21-8.

- ^ Quammen, David (1996). The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions. New York, NY, US: Scribner. p. 318. ISBN 0-684-80083-7.

- ^ Pérez, Francisco L. (October 18, 2021). "The Silent Forest: Impact of Bird Hunting by Prehistoric Polynesians on the Decline and Disappearance of Native Avifauna in Hawaiʻi". Geographies. 1 (3): 192–216. doi:10.3390/geographies1030012. ISSN 2673-7086.

- ^ Fryer, Jonathan (2002-09-14). "Bringing the dodo back to life". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- ^ Martin, Paul S. (1973-03-09). "The Discovery of America: The first Americans may have swept the Western Hemisphere and decimated its fauna within 1000 years". Science. 179 (4077): 969–974. doi:10.1126/science.179.4077.969. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17842155.

- ^ Larkin, P. A. (1977). "An epitaph for the concept of maximum sustained yield". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 106 (1): 1–11. Bibcode:1977TrAFS.106....1L. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1977)106<1:AEFTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Lubchenco, J. (1991). "The Sustainable Biosphere Initiative: An ecological research agenda". Ecology. 72 (2): 371–412. doi:10.2307/2937183. JSTOR 2937183. S2CID 53389188.

- ^ Lee, K. N. (2001). "Sustainability, concept and practice of". In Levin, S. A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. Vol. 5. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 553–568. ISBN 978-0-12-226864-9.

- ^ Naess, A. (1986). "Intrinsic value: Will the defenders of nature please rise?". In Soulé, M. E. (ed.). Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. pp. 153–181. ISBN 978-0-87893-794-3.

- ^ Sessions, G., ed. (1995). Deep Ecology for the 21st Century: Readings on the Philosophy and Practice of the New Environmentalism. Boston: Shambala Books. ISBN 978-1-57062-049-2.

- ^ a b Hardin, Garrett (1968). "The Tragedy of the Commons". Science. 162 (3859): 1243–1248. Bibcode:1968Sci...162.1243H. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. PMID 5699198. Also available at http://www.garretthardinsociety.org/articles/art_tragedy_of_the_commons.html.

- ^ Lloyd, William Forster (1833). Two Lectures on the Checks to Population. Oxford University. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- ^ Bowles, Samuel (2004). Microeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and Evolution. Princeton University Press. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-691-09163-1.

- ^ Ostrom, E. (1992). "The rudiments of a theory of the origins, survival, and performance of common-property institutions". In Bromley, D. W. (ed.). Making the Commons Work: Theory, Practice and Policy. San Francisco: ICS Press.

- ^ Feeny, D.; et al. (1990). "The Tragedy of the Commons: Twenty-two years later". Human Ecology. 18 (1): 1–19. Bibcode:1990HumEc..18....1F. doi:10.1007/BF00889070. PMID 12316894. S2CID 13357517.

- ^ "Will commons sense dawn again in time?". The Japan Times Online.

- ^ "NOAA fisheries glossary". repository.library.noaa.gov. NOAA. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Bolden, E.G., Robinson, W.L. (1999), Wildlife ecology and management 4th ed. Prentice-Hall, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ. ISBN 0-13-840422-4

- ^ Grafton, R.Q.; Kompas, T.; Hilborn, R.W. (2007). "Economics of Overexploitation Revisited". Science. 318 (5856): 1601. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1601G. doi:10.1126/science.1146017. PMID 18063793. S2CID 41738906.

- ^ Rosenberg, A.A. (2003). "Managing to the margins: the overexploitation of fisheries". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 1 (2): 102–106. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0102:MTTMTO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ New Scientist: Guaranteed fish quotas halt commercial free-for-all

- ^ A Rising Tide: Scientists find proof that privatising fishing stocks can avert a disaster The Economist, 18th Sept, 2008.

- ^ "Underlying Causes of Deforestation: UN Report". World Rainforest Movement. Archived from the original on 2001-04-11.

- ^ Conrad, C. (2008-06-21). "Forests of eucalyptus shadowed by questions". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "World's largest aquifer going dry". U.S. Water News Online. February 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ Larsen, J. (2005-04-07). "Disappearing Lakes, Shrinking Seas: Selected Examples". Earth Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ^ epa.gov[dead link]

- ^ Palaniappan, Meena & Gleick, Peter H. (2008). "The World's Water 2008-2009 Ch 1" (PDF). Pacific Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ http://atlas.aaas.org/pdf/63-66.pdf Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine Forest Products

- ^ "Destruction of Renewable Resources".

- ^ Rhymer, Judith M.; Simberloff, Daniel (1996). "Extinction by Hybridization and Introgression". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 27 (1): 83–109. Bibcode:1996AnRES..27...83R. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83. JSTOR 2097230.

- ^ Kannan, R.; James, D. A. (2009). "Effects of climate change on global biodiversity: a review of key literature" (PDF). Tropical Ecology. 50 (1): 31–39. ISSN 0564-3295. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- ^ Mora, C.; et al. (2013). "Biotic and Human Vulnerability to Projected Changes in Ocean Biogeochemistry over the 21st Century". PLOS Biology. 11 (10) e1001682. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001682. PMC 3797030. PMID 24143135.

- ^ Dumont, E. (2012). "Estimated impact of global population growth on future wilderness extent" (PDF). Earth System Dynamics Discussions. 3 (1): 433–452. Bibcode:2012ESDD....3..433D. doi:10.5194/esdd-3-433-2012.

- ^ (2006) "Molecular Pharming" GMO Compass Retrieved November 5, 2009, From "GMO Compass". Archived from the original on 2013-05-03. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ Roopesh, J.; et al. (2008). "Marine organisms: Potential Source for Drug Discovery" (PDF). Current Science. 94 (3): 292.

- ^ Dhillion, S. S.; Svarstad, H.; Amundsen, C.; Bugge, H. C. (September 2002). "Bioprospecting: Effects on Environment and Development". Ambio. 31 (6): 491–493. doi:10.1639/0044-7447(2002)031[0491:beoead]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4315292. PMID 12436849.

- ^ Cole, Andrew (2005). "Looking for new compounds in sea is endangering ecosystem". BMJ. 330 (7504): 1350. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7504.1350-d. PMC 558324. PMID 15947392.

- ^ "COHAB Initiative - on Natural Products and Medicinal Resources". Cohabnet.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-25. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Redford 1992, Fitzgibon et al. 1995, Cuarón 2001.

- ^ Frankham, R.; Ballou, J. D.; Briscoe, D. A. (2002). Introduction to Conservation Genetics. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63014-6.

- ^ Dowding, J. E.; Murphy, E. C. (2001). "The Impact of Predation be Introduced Mammals on Endemic Shorebirds in New Zealand: A Conservation Perspective". Biological Conservation. 99 (1): 47–64. Bibcode:2001BCons..99...47D. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00187-7.

- ^ "IUCN Red List". 2003b.

- ^ "IUCN Red List". 2003c. Retrieved 9 December 2003.

- ^ WCMC. (1992). McComb, J., Groombridge, B., Byford, E., Allan, C., Howland, J., Magin, C., Smith, H., Greenwood, V. and Simpson, L. (1992). World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Chapman and Hall.

- ^ Jackson, D. B.; Fuller, R. J.; Campbell, S. T. (2004). "Long-term Population Changes Among Breeding Shorebirds in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, In Relation to Introduced Hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus)". Biological Conservation. 117 (2): 151–166. Bibcode:2004BCons.117..151J. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00289-1.

- ^ Jones, R. F. (1990). "Farewell to Africa". Audubon. 92: 1547–1551.

- ^ Wilkie, D. S.; Carpenter, J. F. (1999). "Bushmeat hunting in the Congo Basin: An assessment of impacts and options for migration". Biodiversity and Conservation. 8 (7): 927–955. Bibcode:1999BiCon...8..927W. doi:10.1023/A:1008877309871. S2CID 27363244.

- ^ Hemley 1994.

- ^ Primack, R. B. (2002). Essentials of Conservation Biology (3rd ed.). Sunderland: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-719-6.

- ^ The LUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2009).

- ^ "THE EXOTIC PET-DEMIC/UK'S TICKING TIMEBOMB EXPOSED". Born Free Foundation and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. September 2021.

- ^ Collins, Nick (2012-04-12). "Chinese medicines contain traces of endangered animals". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 12, 2012.

- ^ Estes, J. A.; Duggins, D. O.; Rathbun, G. B. (1989). "The ecology of extinctions in kelp forest communities". Conservation Biology. 3 (3): 251–264. Bibcode:1989ConBi...3..252E. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.1989.tb00085.x.

- ^ Dayton, P. K.; Tegner, M. J.; Edwards, P. B.; Riser, K. L. (1998). "Sliding baselines, ghosts, and reduced expectations in kelp forest communities". Ecol. Appl. 8 (2): 309–322. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0309:SBGARE]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Krebs, C. J. (2001). Ecology (5th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-321-04289-7.

Further reading

[edit]- FAO (2005) Overcoming factors of unsustainability and overexploitation in fisheries Fisheries report 782, Rome. ISBN 978-92-5-105449-9

- We've overexploited the planet, now we need to change if we're to survive. Patrick Vallance for The Guardian. July 8, 2022.

Overexploitation

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Core Concepts

Defining Overexploitation

Overexploitation refers to the harvesting or extraction of renewable natural resources, such as wildlife populations, fish stocks, or timber stands, at a rate that exceeds their biological capacity for replenishment through reproduction, growth, or regeneration.[6] This results in progressive depletion of the resource base, potentially leading to population crashes, ecosystem disruption, or species extinction if unchecked.[7] Unlike non-renewable resources, which face inevitable exhaustion regardless of rate, overexploitation targets systems theoretically capable of sustaining yields indefinitely under balanced extraction, but causal dynamics—such as density-dependent growth limitations—render high harvest pressures destabilizing.[8] In ecological models, renewable resource populations follow logistic growth patterns where net increase equals the intrinsic growth rate times population size adjusted for density dependence (rN(1 - N/K), with K as carrying capacity); overexploitation manifests when harvest rates (H) surpass this surplus production, yielding negative population change (dN/dt = rN(1 - N/K) - H < 0).[4] Sustainable harvest principles, such as maximum sustainable yield (MSY), posit an optimal extraction level that maximizes long-term output without collapse, typically around half the carrying capacity for many species, but empirical deviations often occur due to inaccurate parameter estimates or external stressors like environmental variability.[9] Overexploitation thresholds vary by species life history: K-selected species with slow maturation (e.g., large mammals or long-lived fish) exhibit lower resilience to elevated mortality than r-selected ones with rapid turnover.[10] The term encompasses direct anthropogenic removal via hunting, fishing, logging, or gathering, excluding incidental mortality or habitat-mediated declines, though synergies with other pressures (e.g., climate shifts) can accelerate outcomes.[11] Quantitatively, global assessments indicate that approximately 33% of assessed fish stocks were overexploited as of 2020, with harvest levels exceeding MSY by factors of 1.5 to 2 in affected fisheries.[12] This depletion erodes not only target populations but also dependent trophic structures, as functional roles (e.g., predation or seed dispersal) diminish with abundance drops below 10-20% of unfished biomass in many cases.[4] Distinguishing overexploitation requires verifiable data on pre-harvest baselines, harvest metrics, and demographic responses, as subjective perceptions of "sustainability" have historically overestimated replenishment in open-access systems.[13]Causal Mechanisms from First Principles

Harvesters and extractors of renewable resources act to maximize short-term net benefits, where the value of immediate extraction—such as revenue from sales minus direct costs—outweighs perceived future costs, including potential resource scarcity. This behavior stems from individual utility maximization under uncertainty, where present consumption provides certain gains while future regeneration depends on probabilistic ecological factors like reproduction rates and environmental variability. Consequently, extraction effort escalates as long as marginal revenue exceeds marginal cost, often ignoring externalities like reduced yields for others or long-term stock collapse.[5] Biological populations of exploited resources follow logistic growth dynamics, described by the equation , where is population size, is the intrinsic growth rate, and is carrying capacity; sustainable harvesting occurs when removal rates equal this growth at or near maximum sustainable yield (MSY). However, human extraction typically models as , with as catchability, as effort, leading to a steady state where increased drives below MSY levels. In unrestricted access, competition among agents bids up effort until average revenue equals average variable cost, dissipating economic rents and stabilizing biomass at a depleted equilibrium—approximately half of the virgin stock in simple cases—far below levels supporting MSY or maximum economic yield (MEY).[14][15] These mechanisms interact causally through feedback loops: initial high yields incentivize capital investment and technological adoption, which amplify effective effort (e.g., larger vessels or gear), further eroding stock and growth rates, thereby accelerating depletion unless offset by exclusion or quotas. Empirical calibrations of such bioeconomic models to fisheries data confirm that open-access conditions systematically produce overexploitation, with effort levels 2-3 times optimal for MEY, as agents externalize depletion costs across the pool. Population pressures exacerbate this by elevating baseline demand, but the core driver remains the absence of internalized costs, rendering self-restraint individually irrational despite collective harm.[16][17]Theoretical Frameworks

Tragedy of the Commons and Open Access Problems

The tragedy of the commons describes a scenario where individuals, acting rationally in self-interest on a shared resource, collectively overuse it to the point of depletion. Garrett Hardin articulated this in his 1968 Science essay, employing the metaphor of a village commons grazed by multiple herdsmen: each adds livestock to capture private gains from increased output, but the resultant overgrazing imposes unaccounted costs on the shared carrying capacity, yielding ruin for all. This dynamic stems from the divergence between private marginal benefits—which incentivize expansion—and social marginal costs, which include diffused impacts on resource sustainability. Hardin's analysis extends beyond pastures to renewable resources like fisheries and forests, where open sharing without exclusion mechanisms fosters overexploitation. In such systems, users extract without bearing the full depletion costs, eroding stock levels below productive equilibria. The concept underscores causal incentives: absent constraints like property rights or quotas, short-term extraction trumps long-term viability, as no single actor internalizes future yield reductions affecting the collective. Open access problems parallel this, particularly in economic models of fisheries, where resources lack enforceable ownership, allowing free entry. H. Scott Gordon's 1954 framework in the Journal of Political Economy showed that fishers enter until average revenue equals marginal cost, dissipating resource rents and driving harvests beyond maximum sustainable yield.[18] Here, the stock's rent—value from restrained harvesting—is competed away, leaving biomass lower and effort higher than socially optimal.[18] In open access regimes, the absence of rights to exclude or allocate prevents cost internalization, amplifying overexploitation through excessive capital investment in harvesting.[18] This applies to high-seas fisheries or unregulated forests, where entrants ignore stock externalities, converging on zero profits and depleted resources. Empirical patterns in oceanic stocks affirm the model's predictions, with unregulated access correlating to persistent overcapacity and collapses.[19] While institutional arrangements can mitigate commons dilemmas in bounded communities, truly open access—devoid of such norms—consistently yields the predicted tragedy via unbridled individual incentives.[19]Property Rights as a Preventive Mechanism

Well-defined property rights address overexploitation by granting exclusive ownership over resources, thereby aligning individual incentives with long-term sustainability; owners bear the full costs of depletion while capturing future benefits, discouraging short-term excess extraction that dissipates resource rents.[20] This mechanism internalizes externalities inherent in open-access regimes, where users disregard marginal depletion costs, as theorized by economist Harold Demsetz in his 1967 analysis of property rights evolution, which posits that such rights emerge when the value of coordinated management exceeds enforcement costs.[21] Empirical reviews confirm that stronger property rights correlate with reduced overexploitation across resource types, as they enable owners to invest in conservation and enforce access limits, contrasting with commons where unregulated entry drives yields below maximum sustainable levels.[22] In fisheries, individual transferable quotas (ITQs)—which function as de facto property rights by allocating harvest shares that can be traded—have demonstrably curbed overfishing by eliminating the "race to fish" derby, allowing quota holders to optimize timing and reduce waste.[23] Iceland's cod fishery, implementing ITQs in 1991, achieved stock recovery and economic viability without government subsidies by 2020, with vessel operators prioritizing higher-value landings over volume.[24] Similarly, New Zealand's ITQ system, rolled out from 1986, stabilized multiple species' biomasses above collapse thresholds, boosting industry profits by 20-30% through efficient allocation while halving fleet capacity.[25] Private timberland ownership exemplifies this in forestry, where proprietors maintain rotation cycles and replanting to preserve asset value, yielding higher sustainable harvests than state or open-access lands; U.S. non-industrial private forests, comprising 42% of timberland as of 2023, demonstrate renewability through voluntary practices like selective logging, avoiding the clearcut overexploitation seen in unregulated areas.[26] Studies across U.S. states show privately held forests invest more in fire prevention and soil conservation, with harvest rates stabilizing at 80-90% of annual growth increments, compared to public lands prone to political pressures for accelerated cuts.[27] These outcomes underscore property rights' role in fostering stewardship, as owners' residual claimancy incentivizes practices that maximize net present value over immediate liquidation.[28]Historical Evolution

Pre-Industrial Instances

Pre-industrial overexploitation refers to instances of resource depletion occurring before the widespread adoption of mechanized industrial technologies, often driven by hunting, gathering, or early agricultural practices in isolated or limited-access environments. These cases demonstrate that human populations, even at low densities, could drive species to extinction through sustained harvesting exceeding reproductive rates, without the amplifying effects of modern tools or global markets. Archaeological and paleontological evidence reveals patterns of rapid population crashes following human arrival or intensified use, underscoring the vulnerability of naive prey species and slow-reproducing megafauna to unchecked exploitation.[29] One prominent example is the extinction of the nine moa species in New Zealand following Polynesian (Māori) colonization around 1280–1300 AD. These large, flightless ratites, some exceeding 3 meters in height and weighing over 200 kg, had no natural predators and supported a human population estimated at just 1,000–2,000 individuals through intensive hunting. Radiocarbon dating of moa bones and associated kill sites indicates that hunting peaked around 650 years before present, leading to local extirpations within decades and island-wide extinction by approximately 1500 AD, a process completed in under 200 years despite low human density. This overkill was facilitated by fire-driven habitat modification and direct predation, with moa comprising up to 99% of bone assemblages at early sites, evidencing targeted overexploitation rather than incidental bycatch.[30][29] Similarly, the Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), a massive sirenian endemic to the Commander Islands, was driven to extinction within 27 years of its 1741 discovery by Georg Steller during the Bering expedition. With an estimated pre-exploitation population of 1,500–2,700 individuals, the species was hunted at rates exceeding seven times its sustainable yield, primarily for meat and hides by Russian fur traders and indigenous groups using pre-industrial methods like harpooning from shore or small boats. Historical accounts and modeling confirm that wasteful harvesting—often leaving carcasses uneaten—depleted the slow-reproducing, non-migratory population by 1768, marking one of the fastest documented extinctions attributable to direct human overexploitation.[31][32] In Norse Greenland settlements (c. 985–1450 AD), overexploitation of walrus populations for ivory export contributed to socioeconomic decline. Initially abundant in nearby waters, walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) were heavily harvested for tusks traded to Europe, but sustained pressure from Norse hunters, combined with competition from Inuit and broader Arctic depletion, reduced local stocks by the 14th century. Isotopic analysis of ivory artifacts shows sourcing from increasingly distant grounds, indicating serial depletion, which strained the pastoral economy already challenged by climate cooling and soil erosion from overgrazing, ultimately factoring into the abandonment of colonies.[33][34]19th-20th Century Expansion

The expansion of overexploitation during the 19th and early 20th centuries was driven by rapid industrialization, population growth exceeding 1 billion globally by 1927, improved transportation networks like railroads enabling access to remote areas, and technological advancements such as repeating rifles and steam-powered vessels that amplified harvest capacities beyond natural replenishment rates.[35] These factors shifted resource extraction from localized, subsistence levels to commercial scales, often under open-access regimes lacking effective property rights or quotas, leading to precipitous declines in targeted populations.[35] In North American wildlife, the American bison (Bison bison) exemplifies this intensification; estimated at 30–60 million individuals in the early 1800s, the herd plummeted to fewer than 1,000 by 1900 due to commercial hunting fueled by railroad expansion and demand for hides and meat, with annual kills exceeding 5 million in peak years like 1872–1874.[36][37] Similarly, the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), once numbering in the billions and forming flocks darkening skies for days, faced extinction by 1914 from market hunting—facilitated by telegraphed flock locations and efficient netting—and concurrent deforestation of oak-hickory forests essential for mast feeding, reducing breeding colonies from vast communal roosts to isolated remnants by the 1890s.[38][39][40] Marine resources underwent parallel depletion through expanded whaling fleets; in the 19th century, American and European operations targeted right and sperm whales intensively, with New England ports alone processing thousands annually, contributing to regional right whale populations around New Zealand and eastern Australia declining rapidly between 1830 and 1850 due to shore-based and pelagic hunts exceeding recruitment.[41][42] Fisheries for Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) off Newfoundland, exploited commercially since the 1500s, accelerated in the 19th century with dory trawling and steam draggers, sustaining catches of 100,000–200,000 tonnes annually until the mid-20th century but eroding biomass through persistent overharvest without regulatory limits.[43] Terrestrial forestry saw widespread clearing in temperate zones; in North America, U.S. farmers deforested an average of 13.5 square miles daily in the late 19th century to expand agriculture, while Europe and eastern North America lost forests at rates of about 19 million hectares per decade from 1700 to 1850, transitioning to managed regrowth only in the 20th century as timber shortages prompted conservation like the U.S. Forest Service's establishment in 1905.[44][45] These cases illustrate how unchecked market incentives and technological multipliers outpaced ecological carrying capacities, setting precedents for later regulatory responses.[35]Recent Trends Since 2000

Since 2000, the proportion of global marine fish stocks classified as overfished has increased from approximately 33% to 35-37% by 2021, with 62.3% of assessed stocks fished at biologically sustainable levels that year, indicating persistent pressure despite some regional management efforts.[46][47] Overfishing rates have risen annually in recent years, threatening one-third of stocks and driving population declines in species like bluefin tuna, where illegal and unregulated fishing continues to undermine quotas.[48][49] Global deforestation rates have moderated, dropping from 17.6 million hectares per year in 1990-2000 to 10.9 million hectares annually in 2015-2025, yet cumulative tree cover loss reached 517 million hectares between 2001 and 2024, equivalent to 13% of the 2000 forest extent, primarily due to agricultural expansion and logging in tropical regions.[50][51] Non-fire-related forest loss rose 13% in 2024 compared to 2023, though remaining below early-2000s peaks, highlighting uneven progress amid ongoing commodity-driven harvesting.[52] Wildlife populations subject to exploitation have experienced steeper declines than non-utilized ones, averaging 50% reduction from 1970 to 2016, with overexploitation implicated in 26.6% of threatened species assessments; broader vertebrate populations show continued downward trends driven by harvesting alongside habitat pressures.[53][54] Aquifer depletion has accelerated globally since 2000, with rapid groundwater level drops exceeding 0.5 meters per year widespread in arid cropland areas, contributing to sea-level rise at rates rising from 0.035 mm/year in 1900 to 0.57 mm/year by 2000 and continuing upward; in the U.S., depletion totaled about 25 km³ annually from 2000-2008, the highest recent period.[55][56][57]Key Sectors

Fisheries and Aquatic Resources

Overexploitation in fisheries occurs when capture rates exceed the replenishment capacity of fish stocks, primarily due to open-access harvesting without effective quotas or property rights, resulting in population crashes. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) 2025 global assessment, 35.5 percent of assessed marine fish stocks are overfished, meaning they are harvested beyond levels that produce maximum sustainable yield, while 64.5 percent remain within biologically sustainable limits; this proportion of overfished stocks has stabilized since the early 2000s but highlights persistent pressure from expanding fleets and demand.[58][59] A prominent historical case is the 1992 collapse of the northern Atlantic cod fishery off Newfoundland, Canada, where stocks declined to approximately 1 percent of pre-exploitation levels after decades of industrial trawling intensified by technological advances like sonar and larger vessels, which outpaced regulatory efforts.[60] Despite a moratorium on directed fishing imposed in 1992, recovery has been limited, with populations remaining below 10 percent of historical biomass as of 2017, attributed to ongoing bycatch, environmental factors, and illegal harvesting.[61][62] Bluefin tuna species exemplify both overexploitation risks and potential recovery through international management. Pacific bluefin tuna stocks, depleted by overfishing in the late 20th century, rebounded to exceed rebuilding targets a decade early by 2024, enabling an 80 percent quota increase for 2025-2026 to 1,872 metric tons under NOAA oversight, though some regional stocks like Atlantic bluefin remain vulnerable to illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.[63][64] Other aquatic resources, such as shellfish and crustaceans, face similar pressures; for instance, abalone fisheries in South Africa and California have collapsed due to poaching and inadequate enforcement, while Antarctic krill harvests, though currently sustainable at around 400,000 tons annually, raise concerns over ecosystem-wide effects on dependent species like whales amid growing demand for aquaculture feed.[65] Global trends indicate that without strengthened property-based management, overexploitation could intensify with climate-driven shifts in fish distributions, undermining food security for communities reliant on capture fisheries, which supplied 96 million tons in 2022.[66]Forestry and Terrestrial Harvesting

Overexploitation in forestry and terrestrial harvesting occurs when timber and non-timber forest products are extracted at rates surpassing the forests' regenerative capacity, resulting in long-term resource depletion. This process is exacerbated in open-access or weakly governed forests where individual harvesters lack incentives to conserve stocks, leading to rapid exhaustion akin to the tragedy of the commons. Empirical data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) indicate that between 2015 and 2020, the global deforestation rate averaged 10 million hectares annually, with commercial logging contributing significantly to this loss through practices like selective felling and clear-cutting that degrade remaining stands.[67] Illegal logging amplifies overexploitation, accounting for 50% to 90% of timber harvesting in regions such as the Amazon, Central Africa, and Southeast Asia, according to estimates from environmental monitoring. In 2020, Interpol reported that illegal activities resulted in the loss of approximately 10 million hectares of forest worldwide, often involving high-value species harvested without permits or quotas, which undermines sustainable management efforts. Such practices not only deplete mature trees but also fragment habitats, reducing forest resilience to regeneration; for instance, in tropical hardwoods, overharvesting of species like mahogany has led to local extinctions where extraction rates exceeded 1-2% of standing volume annually without compensatory planting.[68] Terrestrial harvesting extends beyond timber to fuelwood and non-timber products, where subsistence demands in developing regions drive unsustainable collection. In sub-Saharan Africa, fuelwood gathering accounts for up to 80% of wood consumption, depleting woodlands at rates of 2-4% per year in high-pressure areas, as documented in FAO assessments. Overexploitation manifests causally through the absence of secure property rights, enabling unchecked access that prioritizes short-term gains over long-term yields; studies show that forests under community or private tenure exhibit 20-50% lower depletion rates compared to state-controlled open-access zones. Mitigation requires enforcing harvest limits backed by monitoring, yet enforcement gaps persist, with global timber trade including up to 30% illegally sourced material entering markets.[69][70]Wildlife and Non-Timber Species

Overexploitation of wildlife has driven numerous species to population collapse or extinction, primarily through unregulated hunting and commercial harvesting in open-access systems. The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), once numbering in the billions across North America, was hunted intensively for meat in the 19th century, with market hunting accelerating its decline; the last wild individual died in 1900, and the species went extinct in captivity by 1914.[40] Commercial exploitation targeted massive nesting colonies, where hunters could kill thousands daily using shotguns and nets, exacerbating vulnerability due to the bird's dependence on large flocks for breeding success.[39] Similarly, New Zealand's moa species, nine giant flightless birds, were hunted to extinction within approximately 100-300 years following Polynesian (Māori) arrival around 1300 AD, with archaeological evidence showing rapid depletion through snares, spears, and consumption of legs for meat.[71] Small human populations sufficed to cause this due to moas' low reproductive rates and lack of predators prior to human arrival.[72] In contemporary contexts, bushmeat trade in Central and West Africa exemplifies ongoing overexploitation, with an estimated 1.6 to 4.6 million metric tons of wildlife harvested annually, leading to sharp biomass declines in hunted species such as duikers and primates.[73] In protected areas, poor fish supplies have correlated with increased bushmeat hunting, resulting in documented reductions for 41 wildlife species between surveys in the 1980s and 2000s.[74] This trade, driven by protein demand and commercial networks, threatens biodiversity hotspots, with unsustainable offtake rates exceeding population growth capacities for many taxa.[75] Non-timber species, including wild plants harvested for medicinal, food, or ornamental uses, face analogous pressures from overcollection without effective ownership incentives. American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), native to eastern North American forests, has experienced range-wide population declines due to overharvesting for export markets, with annual wild harvests decreasing since 1985 amid intensified poaching and habitat fragmentation.[76] Factors like high road density and accessible habitat have amplified harvest rates, pushing many populations below sustainable thresholds despite regulations.[77] In tropical regions, overharvesting of non-timber products like Euterpe edulis palm hearts in Brazilian Atlantic forests has altered regeneration dynamics, reducing seedling survival and shifting forest composition toward less harvestable species.[78] Such cases illustrate how open-access extraction incentivizes short-term gains, depleting slow-growing perennials whose life histories—long maturation times and low fecundity—render them susceptible to boom-and-bust cycles.[79]Water and Aquifer Extraction

Overexploitation of aquifers occurs when groundwater extraction exceeds natural recharge rates, leading to long-term depletion of storage volumes. Globally, groundwater depletion has been estimated at approximately 0.31 mm per year equivalent in sea-level rise contribution from 2002 onward, corresponding to roughly 110 km³ annually, primarily driven by agricultural irrigation demands in arid and semi-arid regions.[80] Peer-reviewed assessments indicate that non-renewable groundwater use, particularly from fossil aquifers, accounts for a significant portion of this loss, with total global depletion rates varying between 145 and 280 km³ per year in major basins during the early 21st century.[81] The Ogallala Aquifer, underlying the U.S. High Plains, exemplifies intensive extraction tied to center-pivot irrigation for crops like corn and wheat. Predevelopment water levels (circa 1950) have declined by an area-weighted average of 16.5 feet through 2019, with localized drops exceeding 100 feet and saturated thickness reduced by over 50% in parts of Texas and Kansas; overall storage loss totals about 410 km³ since the 1930s.[82][57][83] Annual declines averaged 0.6 feet from 2014 to 2015, accelerating pumping costs and threatening irrigation sustainability for 30% of U.S. groundwater-fed agriculture.[84] In northwest India, including Punjab and Haryana, GRACE satellite data reveal depletion rates of approximately 20 gigatons (equivalent to 20 km³) per year from 2002 to 2012, escalating to 54 km³ annually in some assessments through 2008, fueled by subsidized electricity for tube wells irrigating rice and wheat.[85][86] This has resulted in water table drops of up to 1 meter per year in intensively farmed areas, exacerbating reliance on depleting fossil groundwater.[87] Aquifer overexploitation induces consequences such as land subsidence from compaction of dewatered sediments, which has damaged infrastructure in regions like California's Central Valley and Mexico City, where subsidence rates reach meters per decade.[57] In coastal zones, lowered freshwater heads enable saltwater intrusion, contaminating aquifers in Florida and parts of the Nile Delta, rendering groundwater unusable for agriculture or potable supply without desalination.[88][89] Ecosystem impacts include diminished baseflows to rivers, loss of riparian habitats, and heightened vulnerability to drought, as seen in the High Plains where reduced aquifer discharge has altered surface water regimes.[57] These effects compound economic pressures, with global groundwater overdraft linked to billions in annual costs from increased energy for pumping and lost productivity.[90]Ecological Consequences

Population Declines and Biodiversity Loss

Overexploitation of wild populations frequently results in precipitous declines, with targeted species experiencing reductions exceeding 90% in biomass within decades due to harvesting rates surpassing reproductive capacities. In marine fisheries, the northern Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) stocks off Newfoundland collapsed by the early 1990s, dropping from historical levels of approximately 1.6 million metric tons of spawning biomass to less than 50,000 metric tons by 1994, prompting a moratorium on commercial fishing in June 1992 after decades of overfishing intensified since the 1950s.[91][60] Similarly, avian species like the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) saw populations plummet from an estimated 3 to 5 billion individuals in the early 19th century to extinction by 1914, driven primarily by commercial hunting that harvested hundreds of millions annually, disrupting breeding colonies and accelerating demographic collapse.[38][92] These population crashes contribute to biodiversity loss by eroding species richness and genetic diversity within affected taxa. Overharvesting removes individuals selectively, often favoring resilient genotypes and reducing adaptive potential, as observed in exploited shark populations like the sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus), where genetic analyses reveal no recovery signals despite regional protections, indicating persistent low abundance across its range due to historical overexploitation.[93] In terrestrial systems, the extinction of the passenger pigeon exemplifies how overexploitation can eliminate ecologically influential species, leading to secondary declines in dependent forest dynamics, though habitat conversion compounded the direct harvesting pressure.[94] Empirical assessments rank overexploitation as a primary driver of global biodiversity decline, rivaling habitat loss in certain contexts, with analyses of threatened species highlighting its role in 20-30% of assessed vertebrate declines.[95] Amphibian populations provide further evidence, where overexploitation for pet trade and traditional medicine has driven species like certain Neotropical frogs to near-extinction, exacerbating vulnerability to other stressors and contributing to the documented 40% decline rate across amphibian taxa since the 1980s.[96] Such losses manifest in reduced ecosystem services, including pollination and pest control, underscoring overexploitation's cascading effects on community composition and functional diversity.[97] Recovery remains elusive without sustained harvest reductions, as demonstrated by cod stocks that, despite three decades of restrictions, hover at 10-20% of pre-collapse levels as of 2023.[60]Extinction Dynamics

Overexploitation induces extinction when harvesting rates persistently exceed a species' reproductive and recruitment capacity, driving populations toward zero through cumulative demographic deficits. In species with slow maturation, low fecundity, or dependence on large group sizes for breeding success—common in K-selected taxa—initial declines amplify via reduced per capita growth rates, as fewer individuals contribute to replacement. This process often accelerates below critical thresholds, where stochastic events like failed breeding seasons or uneven sex ratios precipitate collapse, independent of further harvesting. Empirical models of harvested populations, incorporating density-dependent growth, show that exceeding maximum sustainable yield by even modest margins can shift trajectories from oscillation to irreversible decline, with extinction probabilities rising sharply once abundance falls below 10-20% of carrying capacity.[98][94] A key dynamic is the anthropogenic Allee effect, where rarity elevates economic value per individual, spurring disproportionate harvest effort and hastening extinction. Unlike natural Allee effects rooted in mating logistics or cooperative behaviors, this bioeconomic feedback creates a self-reinforcing loop: as populations dwindle, prices rise, incentivizing technological adaptations like improved gear or expanded search ranges that maintain or increase offtake despite scarcity. Studies of commercial wildlife trade document this in taxa from abalone to parrots, where market signals override biological limits, pushing systems past recovery points. In simulated fisheries and forestry models, AAE integration reveals extinction risks 2-5 times higher under price-responsive harvesting than fixed-quota scenarios, underscoring how human valuation distorts natural resilience.[99][100] Historical cases illustrate these dynamics in action. The Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), a sirenian restricted to Bering Sea kelp beds, numbered fewer than 2,000 at European contact in 1741; systematic hunting for meat, hides, and oil by Russian explorers and traders eradicated it by 1768, as low mobility and lack of evasion behaviors enabled near-total offtake in under three decades.[101] Similarly, the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), with flocks exceeding 3 billion in the early 19th century, collapsed under commercial net-gun and squab harvesting, which targeted nesting colonies; by 1890, viable flocks vanished, culminating in the death of the last captive individual in 1914, exacerbated by Allee-like dependencies on massive roosts for predator swamping and acorn foraging efficiency.[102] The great auk (Pinguinus impennis), a flightless alcid abundant in North Atlantic colonies until the 18th century, succumbed to feather and egg collection by sailors; intensified exploitation from 1800 onward reduced breeding pairs to dozens, with the final verified killings on Iceland's Eldey Island in June 1844 sealing extinction amid low reproductive output (one egg per pair annually).[103][104] These extinctions highlight vulnerability in island-like or fragmented habitats, where dispersal fails to offset local extirpations, and underscore the role of unregulated markets in overriding intrinsic recovery potential. Quantitative reconstructions indicate harvest intensities of 20-50% annual adult removal sufficed to trigger dynamics in these species, far below levels tolerated by r-selected counterparts. While modern quotas mitigate such cascades in managed stocks, persistent AAE in illicit trades continues to propel near-extinctions, as seen in high-value species like totoaba fish, where bycatch and direct poaching have reduced vaquita porpoise (Phocoena sinus) numbers to under 10 individuals by 2023.[94][105]Cascade and Systemic Effects

Overexploitation often triggers trophic cascades, where the depletion of a key species propagates indirect effects through food webs, altering ecosystem structure and function. In marine systems, the selective removal of apex predators exemplifies this dynamic. For instance, intensive fishing of large sharks in the northwest Atlantic since the mid-20th century released mesopredatory rays and skates from predation pressure, leading to their population booms and subsequent overconsumption of bay scallops, which declined by up to 98% in some areas by the 1990s.[106] This cascade demonstrates how targeting top predators can destabilize benthic communities, reducing prey species and fisheries yields for lower trophic levels. Similarly, historical overharvesting of sea otters along North American coasts in the 19th century caused urchin populations to explode, overgrazing kelp forests and converting productive habitats into urchin barrens, with kelp biomass reductions exceeding 90% in affected regions.[107] Terrestrial overexploitation yields comparable cascades, particularly in rangelands where excessive livestock grazing removes dominant herbivores or vegetation, disrupting soil stability and vegetation succession. Empirical studies in Eurasian steppes show that overgrazing since the 1990s has triggered cascading declines in avian scavengers like vultures, shifting their diets toward less nutritious carrion and reducing breeding success by 20-30% due to altered prey availability and habitat quality.[108] In forested ecosystems, unsustainable logging cascades into soil erosion and nutrient leaching, impairing regeneration and increasing vulnerability to invasive species, as observed in tropical regions where timber overexploitation has led to 50-70% reductions in understory plant diversity within a decade post-harvest.[5] Systemic effects extend beyond immediate cascades to encompass regime shifts and diminished ecosystem services, eroding overall resilience. Overexploited systems exhibit reduced capacity for self-regulation, fostering conditions for invasive proliferations and disease outbreaks; for example, U.S. large marine ecosystems under ecosystem overfishing show heightened invasive species dominance and habitat degradation, with cascading impacts on carbon sequestration and water quality.[109] In aggregate, these dynamics contribute to biodiversity erosion that impairs services like pollination and flood control, with global models indicating that unchecked overexploitation could precipitate 10-20% losses in terrestrial primary productivity by 2050.[110] Such systemic instability underscores the interconnectedness of exploited resources, where localized harvesting amplifies broader ecological feedbacks.Socioeconomic Implications

Human Livelihood and Food Security Effects

Overexploitation of fisheries has led to widespread job losses in communities reliant on commercial and artisanal fishing, with approximately 60 million people employed directly or indirectly in the global fishing sector facing risks from declining stocks.[111] The 1992 collapse of the Atlantic cod fishery off Newfoundland, where northern cod populations fell to 1% of historical levels due to decades of overharvesting, resulted in a moratorium that idled about 35,000 workers, representing roughly 12% of the province's labor force and devastating coastal economies.[112] [113] In regions like western and central Africa, overfishing exacerbates food insecurity by depleting small pelagic fish stocks that provide essential protein for millions, with many species now at risk of extinction and reduced catches threatening nutritional access for vulnerable populations.[114] Globally, fisheries and aquaculture supply 17% of the world's intake of animal protein, but overexploitation-induced inefficiencies, such as a 0.2% annual decline in artisanal fleet catch per unit effort, translate into lost yields that heighten food security risks in protein-dependent developing nations.[115] [116] In forestry, unsustainable harvesting depletes timber and non-timber products critical for rural livelihoods, affecting an estimated 1.6 billion people in developing countries who depend on forests for fuel, construction, and income.[117] Deforestation-driven resource scarcity leads to income losses and food insecurity, as forest-derived foods like fruits, nuts, and game diminish, forcing reliance on less accessible alternatives and exacerbating poverty in affected areas.[118] For instance, in parts of Africa, forest-related activities lift 11% of rural households out of extreme poverty, but overexploitation undermines this buffer, contributing to broader cycles of hunger and economic instability.[119] Wildlife overexploitation, particularly through bushmeat hunting in tropical regions, disrupts subsistence economies and food supplies for indigenous and rural communities, where wild meat constitutes a primary protein source amid limited alternatives.[120] In Central Africa, shifts toward commercial hunting for urban markets have intensified depletion of species like duikers and primates, reducing local availability and threatening nutritional security for hunters' families who once sustained themselves through regulated subsistence practices.[121] Across Africa, declining wildlife populations from habitat loss and overhunting have curtailed contributions to food security, as communities face protein shortfalls without viable substitutes, underscoring the causal link between unchecked extraction and heightened vulnerability to famine.[122]Economic Costs and Resource Valuation

Overexploitation generates substantial economic costs by diminishing renewable resource productivity, eroding future revenues, and incurring restoration or adaptation expenses. In marine fisheries, suboptimal management due to overharvesting results in global annual losses exceeding $80 billion relative to biologically optimal yields, as estimated by analyses of capture fisheries worldwide.[123] The 1992 collapse of the northern Atlantic cod stock off Newfoundland, triggered by decades of excessive harvesting, imposed a cumulative global economic detriment of approximately $76 billion from 1992 to 2010, including forgone landings, processing revenues, and export values.[124] These costs extend beyond direct harvest losses to include unemployment in dependent communities and shifts to less valuable species, amplifying regional GDP contractions. Forestry overexploitation similarly yields high economic tolls through timber stock depletion and ancillary ecosystem service impairments. Annual global losses from forest degradation, driven by unsustainable logging and conversion, total around $379 billion, primarily via reduced soil fertility impacting agricultural output in adjacent lands.[125] Projections indicate that unchecked resource drawdown could precipitate ecological tipping points, averting up to $2.7 trillion in annual global economic damages by 2030 if preventive measures are enacted, encompassing lost carbon sequestration, water regulation, and biodiversity-dependent services.[126] Wildlife overharvesting imposes costs through foregone sustainable yields and market distortions from illegal trade. For elephants and rhinos, poaching erodes potential economic rents from regulated horn and ivory harvesting or ecotourism, with quantitative assessments revealing significant value dissipation in affected populations due to population crashes below viable thresholds.[127] Valuing overexploited resources economically requires integrating market-based metrics, such as producer surplus from sustainable yields, with non-market techniques to capture externalities like habitat resilience. Overuse depletes economic rent—the excess of harvest revenues over extraction costs—while common-pool dynamics incentivize short-term extraction over long-term capital maintenance, leading to empirically observed growth contractions post-depletion.[128][5] Discount rates applied to future resource flows further undervalue preservation, exacerbating overexploitation in models lacking property rights enforcement.[5]Mitigation Strategies

Regulatory and Quota-Based Interventions

Regulatory interventions encompass government-imposed measures such as seasonal closures, gear restrictions, minimum size limits, and protected areas to limit harvest rates and allow population recovery in overexploited resources. Quota-based systems allocate predefined harvest limits, including Total Allowable Catches (TACs) that cap aggregate extraction and Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs) that distribute shares among fishers or hunters, aiming to align incentives with sustainability by creating de facto property rights over portions of the resource.[129][130] In marine fisheries, ITQs have demonstrated capacity to constrain catches effectively, with 94% of managed stocks recording recent harvests at or below quotas by 10% or less, thereby reducing overexploitation risk through controlled effort.[131] Iceland's cod fishery, adopting ITQs in the early 1990s, achieved marked economic gains, including higher vessel productivity and fleet efficiency, while stabilizing stocks post-decline.[24] Similarly, TAC restrictions correlate with biomass recovery and diminished fishing pressure in evaluated cases, as seen in U.S. and international implementations where quotas curbed excess capacity.[132] Combining quotas with spatial closures enhances outcomes by minimizing localized depletion and evasion.[133] Despite these benefits, quota systems frequently underperform due to enforcement gaps, inaccurate stock assessments, and behavioral responses like high-grading or discards in multispecies contexts.[23] In the European Union's Common Fisheries Policy, TACs set from 1990 to 2007 exceeded scientific advice in many instances, failing to halt overfishing across numerous stocks and contributing to persistent depletion.[134] Realized catches often fall short of TACs during rebuilding phases—sometimes by 70-80%—reflecting economic disincentives or regulatory chokes from bycatch limits, though this can inadvertently aid recovery if quotas are science-based.[135] Only about two-thirds of ITQ fisheries succeed in rebuilding overexploited stocks or reversing declines, underscoring that quotas alone do not guarantee biological sustainability without robust monitoring and adaptive adjustments.[131] For terrestrial wildlife, regulatory quotas on hunting and trade, such as those under national game laws or CITES appendices, aim to prevent overhunting but face challenges from illegal markets and poaching, with impact evaluations hampered by incomplete harvest data and enforcement variability.[136] In cases like African elephant ivory quotas prior to 1989 trade bans, lax regulation accelerated population crashes, highlighting the need for stringent compliance to avert quota circumvention. Overall, while quotas mitigate the tragedy of the commons by internalizing externalities, their efficacy hinges on accurate science, verifiable reporting, and penalties exceeding illicit gains, as partial adherence perpetuates depletion.[137]Market and Property Rights Solutions