Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atlantic Ocean

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

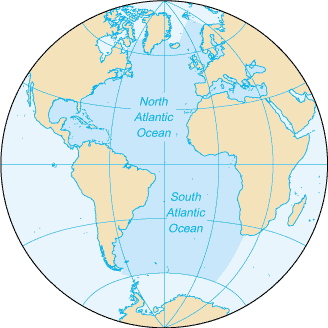

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about 85,133,000 km2 (32,870,000 sq mi).[2] It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for separating the New World of the Americas (North America and South America) from the Old World of Afro-Eurasia (Africa, Asia, and Europe).

Through its separation of Afro-Eurasia from the Americas, the Atlantic Ocean has played a central role in the development of human society, globalization, and the histories of many nations. While the Norse were the first known humans to cross the Atlantic, it was the expedition of Christopher Columbus in 1492 that proved to be the most consequential. Columbus's expedition ushered in an age of exploration and colonization of the Americas by European powers, most notably Portugal, Spain, France, and the United Kingdom. From the 16th to 19th centuries, the Atlantic Ocean was the center of both an eponymous slave trade and the Columbian exchange while occasionally hosting naval battles. Such naval battles, as well as growing trade from regional American powers like the United States and Brazil, both increased in degree during the early 20th century. After World War II, major military operations became rarer, though notable postwar conflicts include the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Falklands War. The ocean remains a core component of trade around the world.

The Atlantic Ocean's temperatures vary by location. For example, the South Atlantic maintains warm temperatures year-round, as its basin countries are tropical. The North Atlantic maintains a temperate climate, as its basin countries are temperate and have seasons of extremely low temperatures and high temperatures.[5]

The Atlantic Ocean occupies an elongated, S-shaped basin extending longitudinally between Europe and Africa to the east, and the Americas to the west. As one component of the interconnected World Ocean, it is connected in the north to the Arctic Ocean, to the Pacific Ocean in the southwest, the Indian Ocean in the southeast, and the Southern Ocean in the south. Other definitions describe the Atlantic as extending southward to Antarctica. The Atlantic Ocean is divided in two parts, the northern and southern Atlantic, by the Equator.[6]

Toponymy

[edit]

The oldest known mentions of an "Atlantic" sea come from Stesichorus around mid-sixth century BC (Sch. A. R. 1. 211):[7] Atlantikôi pelágei (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντικῷ πελάγει, 'the Atlantic sea', etym. 'Sea of Atlas') and in The Histories of Herodotus around 450 BC (Hdt. 1.202.4): Atlantis thalassa (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντὶς θάλασσα, 'Sea of Atlas' or 'the Atlantic sea'[8]) where the name refers to "the sea beyond the pillars of Hercules" which is said to be part of the sea that surrounds all land.[9] In these uses, the name refers to Atlas, the Titan in Greek mythology, who supported the heavens and who later appeared as a frontispiece in medieval maps and also lent his name to modern atlases.[10] On the other hand, to early Greek sailors and in ancient Greek mythological literature such as the Iliad and the Odyssey, this all-encompassing ocean was instead known as Oceanus, the gigantic river that encircled the world; in contrast to the enclosed seas well known to the Greeks: the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.[11] In contrast, the term "Atlantic" originally referred specifically to the Atlas Mountains in Morocco and the sea off the Strait of Gibraltar and the West African coast.[10]

The term "Aethiopian Ocean", derived from Ancient Ethiopia, was applied to the southern Atlantic as late as the mid-19th century.[12] During the Age of Discovery, the Atlantic was also known to English cartographers as the Great Western Ocean.[13]

The pond is a term often used by British and American speakers in reference to the northern Atlantic Ocean, as a form of meiosis, or ironic understatement. It is used mostly when referring to events or circumstances "on this side of the pond" or "on the other side of the pond" or "across the pond", rather than to discuss the ocean itself.[14] The term dates to 1640, first appearing in print in a pamphlet released during the reign of Charles I, and reproduced in 1869 in Nehemiah Wallington's Historical Notices of Events Occurring Chiefly in The Reign of Charles I, where "great Pond" is used in reference to the Atlantic Ocean by Francis Windebank, Charles I's Secretary of State.[15][16][17]

Extent and data

[edit]The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) defined the limits of the oceans and seas in 1953,[18] but some of these definitions have been revised since then and some are not recognized by various authorities, institutions, and countries, for example the CIA World Factbook. Correspondingly, the extent and number of oceans and seas vary.

The Atlantic Ocean is bounded on the west by North and South America. It connects to the Arctic Ocean through the Labrador Sea, Denmark Strait, Greenland Sea, Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea with the northern divider passing through Iceland and Svalbard. To the east, the boundaries of the ocean proper are Europe and Africa: the Strait of Gibraltar (where it connects with the Mediterranean Sea – one of its marginal seas – and, in turn, the Black Sea, both of which also touch upon Asia).

In the southeast, the Atlantic merges into the Indian Ocean. The 20° East meridian, running south from Cape Agulhas to Antarctica defines its border. In the 1953 definition it extends south to Antarctica, while in later maps it is bounded at the 60° parallel by the Southern Ocean.[18]

The Atlantic has irregular coasts indented by numerous bays, gulfs and seas. These include the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Caribbean Sea, Davis Strait, Denmark Strait, part of the Drake Passage, Gulf of Mexico, Labrador Sea, Mediterranean Sea, North Sea, Norwegian Sea, almost all of the Scotia Sea, and other tributary water bodies.[1] Including these marginal seas the coast line of the Atlantic measures 111,866 km (69,510 mi) compared to 135,663 km (84,297 mi) for the Pacific.[1][19]

Including its marginal seas, the Atlantic covers an area of 106,460,000 km2 (41,100,000 sq mi) or 23.5% of the global ocean and has a volume of 310,410,900 km3 (74,471,500 cu mi) or 23.3% of the total volume of the Earth's oceans. Excluding its marginal seas, the Atlantic covers 81,760,000 km2 (31,570,000 sq mi) and has a volume of 305,811,900 km3 (73,368,200 cu mi). The North Atlantic covers 41,490,000 km2 (16,020,000 sq mi) (11.5%) and the South Atlantic 40,270,000 km2 (15,550,000 sq mi) (11.1%).[3] The average depth is 3,646 m (11,962 ft) and the maximum depth, the Milwaukee Deep in the Puerto Rico Trench, is 8,376 m (27,480 ft).[20][21]

Bathymetry

[edit]

The bathymetry of the Atlantic is dominated by a submarine mountain range called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR). It runs from 87°N or 300 km (190 mi) south of the North Pole to the subantarctic Bouvet Island at 54°S.[22] Expeditions to explore the bathymertry of the Atlantic include the Challenger expedition and the German Meteor expedition; as of 2001[update], Columbia University's Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory and the United States Navy Hydrographic Office conduct research on the ocean.[23]

Mid-Atlantic Ridge

[edit]The MAR divides the Atlantic longitudinally into two halves, in each of which a series of basins are delimited by secondary, transverse ridges. The MAR reaches above 2,000 m (6,600 ft) along most of its length, but is interrupted by larger transform faults at two places: the Romanche Trench near the Equator and the Gibbs fracture zone at 53°N. The MAR is a barrier for bottom water, but at these two transform faults deep water currents can pass from one side to the other.[24]

The MAR rises 2–3 km (1.2–1.9 mi) above the surrounding ocean floor and its rift valley is the divergent boundary between the North American and Eurasian plates in the North Atlantic and the South American and African plates in the South Atlantic. The MAR produces basaltic volcanoes in Eyjafjallajökull, Iceland, and pillow lava on the ocean floor.[25] The depth of water at the apex of the ridge is less than 2,700 m (1,500 fathoms; 8,900 ft) in most places, while the bottom of the ridge is three times as deep.[26]

The MAR is intersected by two perpendicular ridges: the Azores–Gibraltar transform fault, the boundary between the Nubian and Eurasian plates, intersects the MAR at the Azores triple junction, on either side of the Azores microplate, near the 40°N.[27] A much vaguer, nameless boundary, between the North American and South American plates, intersects the MAR near or just north of the Fifteen-Twenty fracture zone, approximately at 16°N.[28]

In the 1870s, the Challenger expedition discovered parts of what is now known as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, or:

An elevated ridge rising to an average height of about 1,900 fathoms [3,500 m; 11,400 ft] below the surface traverses the basins of the North and South Atlantic in a meridianal direction from Cape Farewell, probably its far south at least as Gough Island, following roughly the outlines of the coasts of the Old and the New Worlds.[29]

The remainder of the ridge was discovered in the 1920s by the German Meteor expedition using echo-sounding equipment.[30] The exploration of the MAR in the 1950s led to the general acceptance of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics.[22]

Most of the MAR runs under water but where it reaches the surfaces it has produced volcanic islands. While nine of these have collectively been nominated a World Heritage Site for their geological value, four of them are considered of "Outstanding Universal Value" based on their cultural and natural criteria: Þingvellir, Iceland; Landscape of the Pico Island Vineyard Culture, Portugal; Gough and Inaccessible Islands, United Kingdom; and Brazilian Atlantic Islands: Fernando de Noronha and Atol das Rocas Reserves, Brazil.[22]

Ocean floor

[edit]Continental shelves in the Atlantic are wide off Newfoundland, southernmost South America, and northeastern Europe. In the western Atlantic carbonate platforms dominate large areas, for example, the Blake Plateau and Bermuda Rise. The Atlantic is surrounded by passive margins except at a few locations where active margins form deep trenches: the Puerto Rico Trench (8,376 m or 27,480 ft maximum depth) in the western Atlantic and South Sandwich Trench (8,264 m or 27,113 ft) in the South Atlantic. There are numerous submarine canyons off northeastern North America, western Europe, and northwestern Africa. Some of these canyons extend along the continental rises and farther into the abyssal plains as deep-sea channels.[24]

In 1922, a historic moment in cartography and oceanography occurred. The USS Stewart used a Navy Sonic Depth Finder to draw a continuous map across the bed of the Atlantic. This involved little guesswork because the idea of sonar is straightforward with pulses being sent from the vessel, which bounce off the ocean floor, then return to the vessel.[31] The deep ocean floor is thought to be fairly flat with occasional deeps, abyssal plains, trenches, seamounts, basins, plateaus, canyons, and some guyots. Various shelves along the margins of the continents constitute about 11% of the bottom topography with few deep channels cut across the continental rise.

The mean depth between 60°N and 60°S is 3,730 m (12,240 ft), or close to the average for the global ocean, with a modal depth between 4,000 and 5,000 m (13,000 and 16,000 ft).[24]

In the South Atlantic the Walvis Ridge and Rio Grande Rise form barriers to ocean currents. The Laurentian Abyss is found off the eastern coast of Canada.

Water characteristics

[edit]

Surface water temperatures, which vary with latitude, current systems, and season and reflect the latitudinal distribution of solar energy, range from below −2 °C (28 °F) to over 30 °C (86 °F). Maximum temperatures occur north of the equator, and minimum values are found in the polar regions. In the middle latitudes, the area of maximum temperature variations, values may vary by 7–8 °C (13–14 °F).[23]

From October to June the surface is usually covered with sea ice in the Labrador Sea, Denmark Strait, and Baltic Sea.[23][failed verification]

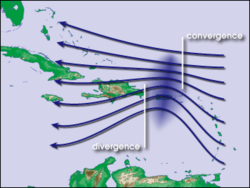

The Coriolis effect circulates North Atlantic water in a clockwise direction, whereas South Atlantic water circulates counter-clockwise. The south tides in the Atlantic Ocean are semi-diurnal; that is, two high tides occur every 24 lunar hours. In latitudes above 40° North some east–west oscillation, known as the North Atlantic oscillation, occurs.[23]

Salinity

[edit]On average, the Atlantic is the saltiest major ocean; surface water salinity in the open ocean ranges from 33 to 37 parts per thousand (3.3–3.7%) by mass and varies with latitude and season. Evaporation, precipitation, river inflow and sea ice melting influence surface salinity values. Although the lowest salinity values are just north of the equator (because of heavy tropical rainfall), in general, the lowest values are in the high latitudes and along coasts where large rivers enter. Maximum salinity values occur at about 25° north and south, in subtropical regions with low rainfall and high evaporation.[23]

The high surface salinity in the Atlantic, on which the Atlantic thermohaline circulation is dependent, is maintained by two processes: the Agulhas Leakage/Rings, which brings salty Indian Ocean waters into the South Atlantic, and the "Atmospheric Bridge", which evaporates subtropical Atlantic waters and exports it to the Pacific.[32]

Water masses

[edit]| Water mass | Temperature | Salinity |

|---|---|---|

| Upper waters (0–500 m or 0–1,600 ft) | ||

| Atlantic Subarctic Upper Water (ASUW) |

0.0–4.0 °C | 34.0–35.0 |

| Western North Atlantic Central Water (WNACW) |

7.0–20 °C | 35.0–36.7 |

| Eastern North Atlantic Central Water (ENACW) |

8.0–18.0 °C | 35.2–36.7 |

| South Atlantic Central Water (SACW) |

5.0–18.0 °C | 34.3–35.8 |

| Intermediate waters (500–1,500 m or 1,600–4,900 ft) | ||

| Western Atlantic Subarctic Intermediate Water (WASIW) |

3.0–9.0 °C | 34.0–35.1 |

| Eastern Atlantic Subarctic Intermediate Water (EASIW) |

3.0–9.0 °C | 34.4–35.3 |

| Mediterranean Water (MW) | 2.6–11.0 °C | 35.0–36.2 |

| Arctic Intermediate Water (AIW) | −1.5–3.0 °C | 34.7–34.9 |

| Deep and abyssal waters (1,500 m–bottom or 4,900 ft–bottom) | ||

| North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) |

1.5–4.0 °C | 34.8–35.0 |

| Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) | −0.9–1.7 °C | 34.6–34.7 |

| Arctic Bottom Water (ABW) | −1.8 to −0.5 °C | 34.9–34.9 |

The Atlantic Ocean consists of four major, upper water masses with distinct temperature and salinity. The Atlantic subarctic upper water in the northernmost North Atlantic is the source for subarctic intermediate water and North Atlantic intermediate water. North Atlantic central water can be divided into the eastern and western North Atlantic central water since the western part is strongly affected by the Gulf Stream and therefore the upper layer is closer to underlying fresher subpolar intermediate water. The eastern water is saltier because of its proximity to Mediterranean water. North Atlantic central water flows into South Atlantic central water at 15°N.[34]

There are five intermediate waters: four low-salinity waters formed at subpolar latitudes and one high-salinity formed through evaporation. Arctic intermediate water flows from the north to become the source for North Atlantic deep water, south of the Greenland-Scotland sill. These two intermediate waters have different salinity in the western and eastern basins. The wide range of salinities in the North Atlantic is caused by the asymmetry of the northern subtropical gyre and a large number of contributions from a wide range of sources: Labrador Sea, Norwegian-Greenland Sea, Mediterranean, and South Atlantic Intermediate Water.[34]

The North Atlantic deep water (NADW) is a complex of four water masses, two that form by deep convection in the open ocean – classical and upper Labrador sea water – and two that form from the inflow of dense water across the Greenland-Iceland-Scotland sill – Denmark Strait and Iceland-Scotland overflow water. Along its path across Earth the composition of the NADW is affected by other water masses, especially Antarctic bottom water and Mediterranean overflow water.[35] The NADW is fed by a flow of warm shallow water into the northern North Atlantic which is responsible for the anomalous warm climate in Europe. Changes in the formation of NADW have been linked to global climate changes in the past. Since human-made substances were introduced into the environment, the path of the NADW can be traced throughout its course by measuring tritium and radiocarbon from nuclear weapon tests in the 1960s and CFCs.[36]

Gyres

[edit]The clockwise warm-water North Atlantic Gyre occupies the northern Atlantic, and the counter-clockwise warm-water South Atlantic Gyre appears in the southern Atlantic.[23]

In the North Atlantic, surface circulation is dominated by three inter-connected currents: the Gulf Stream which flows north-east from the North American coast at Cape Hatteras; the North Atlantic Current, a branch of the Gulf Stream which flows northward from the Grand Banks; and the Subpolar Front, an extension of the North Atlantic Current, a wide, vaguely defined region separating the subtropical gyre from the subpolar gyre. This system of currents transports warm water into the North Atlantic, without which temperatures in the North Atlantic and Europe would plunge dramatically.[37]

North of the North Atlantic Gyre, the cyclonic North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre plays a key role in climate variability. It is governed by ocean currents from marginal seas and regional topography, rather than being steered by wind, both in the deep ocean and at sea level.[38] The subpolar gyre forms an important part of the global thermohaline circulation. Its eastern portion includes eddying branches of the North Atlantic Current which transport warm, saline waters from the subtropics to the northeastern Atlantic. There this water is cooled during winter and forms return currents that merge along the eastern continental slope of Greenland where they form an intense (40–50 Sv) current which flows around the continental margins of the Labrador Sea. A third of this water becomes part of the deep portion of the North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW). The NADW, in turn, feeds the meridional overturning circulation (MOC), the northward heat transport of which is threatened by anthropogenic climate change. Large variations in the subpolar gyre on a decade-century scale, associated with the North Atlantic oscillation, are especially pronounced in Labrador Sea Water, the upper layers of the MOC.[39]

The South Atlantic is dominated by the anti-cyclonic southern subtropical gyre. The South Atlantic Central Water originates in this gyre, while Antarctic Intermediate Water originates in the upper layers of the circumpolar region, near the Drake Passage and the Falkland Islands. Both these currents receive some contribution from the Indian Ocean. On the African east coast, the small cyclonic Angola Gyre lies embedded in the large subtropical gyre.[40] The southern subtropical gyre is partly masked by a wind-induced Ekman layer. The residence time of the gyre is 4.4–8.5 years. North Atlantic Deep Water flows southward below the thermocline of the subtropical gyre.[41]

Sargasso Sea

[edit]The Sargasso Sea in the western North Atlantic can be defined as the area where two species of Sargassum (S. fluitans and natans) float, an area 4,000 km (2,500 mi) wide and encircled by the Gulf Stream, North Atlantic Drift, and North Equatorial Current. This population of seaweed probably originated from Tertiary ancestors on the European shores of the former Tethys Ocean and has, if so, maintained itself by vegetative growth, floating in the ocean for millions of years.[42]

Other species endemic to the Sargasso Sea include the sargassum fish, a predator with algae-like appendages which hovers motionless among the Sargassum. Fossils of similar fishes have been found in fossil bays of the former Tethys Ocean, in what is now the Carpathian region, that were similar to the Sargasso Sea. It is possible that the population in the Sargasso Sea migrated to the Atlantic as the Tethys closed at the end of the Miocene around 17 Ma.[42] The origin of the Sargasso fauna and flora remained enigmatic for centuries. The fossils found in the Carpathians in the mid-20th century often called the "quasi-Sargasso assemblage", finally showed that this assemblage originated in the Carpathian Basin from where it migrated over Sicily to the central Atlantic where it evolved into modern species of the Sargasso Sea.[43]

The location of the spawning ground for European eels remained unknown for decades. In the early 19th century it was discovered that the southern Sargasso Sea is the spawning ground for both the European and American eel and that the former migrate more than 5,000 km (3,100 mi) and the latter 2,000 km (1,200 mi). Ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream transport eel larvae from the Sargasso Sea to foraging areas in North America, Europe, and northern Africa.[44] Recent but disputed research suggests that eels possibly use Earth's magnetic field to navigate through the ocean both as larvae and as adults.[45]

Climate

[edit]

The climate is influenced by the temperatures of the surface waters and water currents as well as winds. Because of the ocean's great capacity to store and release heat, maritime climates are more moderate and have less extreme seasonal variations than inland climates. Precipitation can be approximated from coastal weather data and air temperature from water temperatures.[23]

The oceans are the major source of atmospheric moisture that is obtained through evaporation. Climatic zones vary with latitude; the warmest zones stretch across the Atlantic north of the equator. The coldest zones are in high latitudes, with the coldest regions corresponding to the areas covered by sea ice. Ocean currents influence the climate by transporting warm and cold waters to other regions. The winds that are cooled or warmed when blowing over these currents influence adjacent land areas.[23]

The Gulf Stream and its northern extension towards Europe, the North Atlantic Drift is thought to have at least some influence on climate. For example, the Gulf Stream helps moderate winter temperatures along the coastline of southeastern North America, keeping it warmer in winter along the coast than inland areas. The Gulf Stream also keeps extreme temperatures from occurring on the Florida Peninsula. In the higher latitudes, the North Atlantic Drift, warms the atmosphere over the oceans, keeping the British Isles and northwestern Europe mild and cloudy, and not severely cold in winter, like other locations at the same high latitude. The cold water currents contribute to heavy fog off the coast of eastern Canada (the Grand Banks of Newfoundland area) and Africa's northwestern coast. In general, winds transport moisture and air over land areas.[23]

Natural hazards

[edit]

Every winter, the Icelandic Low produces frequent storms. Icebergs are common from early February to the end of July across the shipping lanes near the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. The ice season is longer in the polar regions, but there is little shipping in those areas.[46]

Hurricanes are a hazard in the western parts of the North Atlantic during the summer and autumn. Due to a consistently strong wind shear and a weak Intertropical Convergence Zone, South Atlantic tropical cyclones are rare.[47]

Geology and plate tectonics

[edit]The Atlantic Ocean is underlain mostly by dense mafic oceanic crust made up of basalt and gabbro and overlain by fine clay, silt and siliceous ooze on the abyssal plain. The continental margins and continental shelf mark lower density, but greater thickness felsic continental rock that is often much older than that of the seafloor. The oldest oceanic crust in the Atlantic is up to 145 million years and is situated off the west coast of Africa and the east coast of North America, or on either side of the South Atlantic.[48]

In many places, the continental shelf and continental slope are covered in thick sedimentary layers. For instance, on the North American side of the ocean, large carbonate deposits formed in warm shallow waters such as Florida and the Bahamas, while coarse river outwash sands and silt are common in shallow shelf areas like the Georges Bank. Coarse sand, boulders, and rocks were transported into some areas, such as off the coast of Nova Scotia or the Gulf of Maine during the Pleistocene ice ages.[49]

Central Atlantic

[edit]The break-up of Pangaea began in the central Atlantic, between North America and Northwest Africa, where rift basins opened during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. This period also saw the first stages of the uplift of the Atlas Mountains. The exact timing is controversial with estimates ranging from 200 to 170 Ma.[50]

The opening of the Atlantic Ocean coincided with the initial break-up of the supercontinent Pangaea, both of which were initiated by the eruption of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP), one of the most extensive and voluminous large igneous provinces in Earth's history associated with the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, one of Earth's major extinction events.[51] Theoliitic dikes, sills, and lava flows from the CAMP eruption at 200 Ma have been found in West Africa, eastern North America, and northern South America. The extent of the volcanism has been estimated to 4.5×106 km2 (1.7×106 sq mi) of which 2.5×106 km2 (9.7×105 sq mi) covered what is now northern and central Brazil.[52]

The formation of the Central American Isthmus closed the Central American Seaway at the end of the Pliocene 2.8 Ma ago. The formation of the isthmus resulted in the migration and extinction of many land-living animals, known as the Great American Interchange, but the closure of the seaway resulted in a "Great American Schism" as it affected ocean currents, salinity, and temperatures in both the Atlantic and Pacific. Marine organisms on both sides of the isthmus became isolated and either diverged or went extinct.[53]

North Atlantic

[edit]Geologically, the North Atlantic is the area delimited to the south by two conjugate margins, Newfoundland and Iberia, and to the north by the Arctic Eurasian Basin. The opening of the North Atlantic closely followed the margins of its predecessor, the Iapetus Ocean, and spread from the central Atlantic in six stages: Iberia–Newfoundland, Porcupine–North America, Eurasia–Greenland, Eurasia–North America. Active and inactive spreading systems in this area are marked by the interaction with the Iceland hotspot.[54]

Seafloor spreading led to the extension of the crust and the formation of troughs and sedimentary basins. The Rockall Trough opened between 105 and 84 million years ago although the rift failed along with one leading into the Bay of Biscay.[55]

Spreading began opening the Labrador Sea around 61 million years ago, continuing until 36 million years ago. Geologists distinguish two magmatic phases. One from 62 to 58 million years ago predates the separation of Greenland from northern Europe while the second from 56 to 52 million years ago happened as the separation occurred.

Iceland began to form 62 million years ago due to a particularly concentrated mantle plume. Large quantities of basalt erupted at this time period are found on Baffin Island, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Scotland, with ash falls in Western Europe acting as a stratigraphic marker.[56] The opening of the North Atlantic caused a significant uplift of continental crust along the coast. For instance, despite 7 km thick basalt, Gunnbjorn Field in East Greenland is the highest point on the island, elevated enough that it exposes older Mesozoic sedimentary rocks at its base, similar to old lava fields above sedimentary rocks in the uplifted Hebrides of western Scotland.[57]

The North Atlantic Ocean contains about 810 seamounts, most of them situated along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.[58] The OSPAR database (Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic) mentions 104 seamounts: 74 within national exclusive economic zones. Of these seamounts, 46 are located close to the Iberian Peninsula.

South Atlantic

[edit]West Gondwana (South America and Africa) broke up in the Early Cretaceous to form the South Atlantic. The apparent fit between the coastlines of the two continents was noted on the first maps that included the South Atlantic and it was also the subject of the first computer-assisted plate tectonic reconstructions in 1965.[59][60] This magnificent fit, however, has since then proven problematic and later reconstructions have introduced various deformation zones along the shorelines to accommodate the northward-propagating break-up.[59] Intra-continental rifts and deformations have also been introduced to subdivide both continental plates into sub-plates.[61]

Geologically, the South Atlantic can be divided into four segments: equatorial segment, from 10°N to the Romanche fracture zone (RFZ); central segment, from RFZ to Florianopolis fracture zone (FFZ, north of Walvis Ridge and Rio Grande Rise); southern segment, from FFZ to the Agulhas–Falkland fracture zone (AFFZ); and Falkland segment, south of AFFZ.[62]

In the southern segment the Early Cretaceous (133–130 Ma) intensive magmatism of the Paraná–Etendeka Large Igneous Province produced by the Tristan hotspot resulted in an estimated volume of 1.5×106 to 2.0×106 km3 (3.6×105 to 4.8×105 cu mi). It covered an area of 1.2×106 to 1.6×106 km2 (4.6×105 to 6.2×105 sq mi) in Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay and 0.8×105 km2 (3.1×104 sq mi) in Africa. Dyke swarms in Brazil, Angola, eastern Paraguay, and Namibia, however, suggest the LIP originally covered a much larger area and also indicate failed rifts in all these areas. Associated offshore basaltic flows reach as far south as the Falkland Islands and South Africa. Traces of magmatism in both offshore and onshore basins in the central and southern segments have been dated to 147–49 Ma with two peaks between 143 and 121 Ma and 90–60 Ma.[62]

In the Falkland segment rifting began with dextral movements between the Patagonia and Colorado sub-plates between the Early Jurassic (190 Ma) and the Early Cretaceous (126.7 Ma). Around 150 Ma sea-floor spreading propagated northward into the southern segment. No later than 130 Ma rifting had reached the Walvis Ridge–Rio Grande Rise.[61]

In the central segment, rifting started to break Africa in two by opening the Benue Trough around 118 Ma. Rifting in the central segment, however, coincided with the Cretaceous Normal Superchron (also known as the Cretaceous quiet period), a 40 Ma period without magnetic reversals, which makes it difficult to date sea-floor spreading in this segment.[61]

The equatorial segment is the last phase of the break-up, but, because it is located on the Equator, magnetic anomalies cannot be used for dating. Various estimates date the propagation of seafloor spreading in this segment and consequent opening of the Equatorial Atlantic Gateway (EAG) to the period 120–96 Ma.[63][64] This final stage, nevertheless, coincided with or resulted in the end of continental extension in Africa.[61]

About 50 Ma the opening of the Drake Passage resulted from a change in the motions and separation rate of the South American and Antarctic plates. First, small ocean basins opened and a shallow gateway appeared during the Middle Eocene. 34–30 Ma a deeper seaway developed, followed by an Eocene–Oligocene climatic deterioration and the growth of the Antarctic ice sheet.[65]

Closure of the Atlantic

[edit]An embryonic subduction margin is potentially developing west of Gibraltar. The Gibraltar Arc in the western Mediterranean is migrating westward into the central Atlantic where it joins the converging African and Eurasian plates. Together these three tectonic forces are slowly developing into a new subduction system in the eastern Atlantic Basin. Meanwhile, the Scotia Arc and Caribbean plate in the western Atlantic Basin are eastward-propagating subduction systems that might, together with the Gibraltar system, represent the beginning of the closure of the Atlantic Ocean and the final stage of the Atlantic Wilson cycle.[66]

History

[edit]Old World

[edit]Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) studies indicate that 80,000–60,000 years ago a major demographic expansion within Africa, derived from a single, small population, coincided with the emergence of behavioral complexity and the rapid MIS 5–4 environmental changes. This group of people not only expanded over the whole of Africa, but also started to disperse out of Africa into Asia, Europe, and Australasia around 65,000 years ago and quickly replaced the archaic humans in these regions.[67] During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) 20,000 years ago humans had to abandon their initial settlements along the European North Atlantic coast and retreat to the Mediterranean. Following rapid climate changes at the end of the LGM this region was repopulated by Magdalenian culture. Other hunter-gatherers followed in waves interrupted by hazards such as the Laacher See volcanic eruption, the inundation of Doggerland (now the North Sea), and the formation of the Baltic Sea.[68] The European coasts of the North Atlantic were permanently populated about 9,000–8.5,000 years ago.[69]

This human dispersal left abundant traces along the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean. 50 kya-old, deeply stratified shell middens found in Ysterfontein on the western coast of South Africa are associated with the Middle Stone Age (MSA). The MSA population was small and dispersed and the rate of their reproduction and exploitation was less intense than those of later generations. While their middens resemble 12–11 kya-old Late Stone Age (LSA) middens found on every inhabited continent, the 50–45 kya-old Enkapune Ya Muto in Kenya probably represents the oldest traces of the first modern humans to disperse out of Africa.[70]

The same development can be seen in Europe. In La Riera Cave (23–13 kya) in Asturias, Spain, only some 26,600 molluscs were deposited over 10 kya. In contrast, 8–7 kya-old shell middens in Portugal, Denmark, and Brazil generated thousands of tons of debris and artefacts. The Ertebølle middens in Denmark, for example, accumulated 2,000 m3 (71,000 cu ft) of shell deposits representing some 50 million molluscs over only a thousand years. This intensification in the exploitation of marine resources has been described as accompanied by new technologies – such as boats, harpoons, and fish hooks – because many caves found in the Mediterranean and on the European Atlantic coast have increased quantities of marine shells in their upper levels and reduced quantities in their lower. The earliest exploitation took place on the submerged shelves, now submerged and most settlements now excavated were then located several kilometers from these shelves. The reduced quantities of shells in the lower levels can represent the few shells that were exported inland.[71]

New World

[edit]During the LGM the Laurentide Ice Sheet covered most of northern North America while Beringia connected Siberia to Alaska. In 1973, late American geoscientist Paul S. Martin proposed a "blitzkrieg" colonization of the Americas by which Clovis hunters migrated into North America around 13,000 years ago in a single wave through an ice-free corridor in the ice sheet and "spread southward explosively, briefly attaining a density sufficiently large to overkill much of their prey."[72] Others later proposed a "three-wave" migration over the Bering Land Bridge.[73] These hypotheses remained the long-held view regarding the settlement of the Americas, a view challenged by more recent archaeological discoveries: the oldest archaeological sites in the Americas have been found in South America; sites in northeast Siberia report virtually no human presence there during the LGM; and most Clovis artefacts have been found in eastern North America along the Atlantic coast.[74] Furthermore, colonisation models based on mtDNA, yDNA, and atDNA data respectively support neither the "blitzkrieg" nor the "three-wave" hypotheses but they also deliver mutually ambiguous results. Contradictory data from archaeology and genetics will most likely deliver future hypotheses that will, eventually, confirm each other.[75] A proposed route across the Pacific to South America could explain early South American finds and another hypothesis proposes a northern path, through the Canadian Arctic and down the North American Atlantic coast.[76] Early settlements across the Atlantic have been suggested by alternative theories, ranging from purely hypothetical to mostly disputed, including the Solutrean hypothesis and some of the Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories.

The Norse settlement of the Faroe Islands and Iceland began during the 9th and 10th centuries. A settlement on Greenland was established before 1000 CE, but contact with it was lost in 1409 and it was finally abandoned during the early Little Ice Age. This setback was caused by a range of factors: an unsustainable economy resulted in erosion and denudation, while conflicts with the local Inuit resulted in the failure to adapt their Arctic technologies; a colder climate resulted in starvation, and the colony got economically marginalized as the Great Plague harvested its victims on Iceland in the 15th century.[77] Iceland was initially settled 865–930 CE following a warm period when winter temperatures hovered around 2 °C (36 °F) which made farming favorable at high latitudes. This did not last, however, and temperatures quickly dropped; at 1080 CE summer temperatures had reached a maximum of 5 °C (41 °F). The Landnámabók (Book of Settlement) records disastrous famines during the first century of settlement – "men ate foxes and ravens" and "the old and helpless were killed and thrown over cliffs" – and by the early 1200s hay had to be abandoned for short-season crops such as barley.[78]

Atlantic World

[edit]

Christopher Columbus reached the Americas in 1492, sailing under the Spanish flag.[79] Six years later Vasco da Gama reached India under the Portuguese flag, by navigating south around the Cape of Good Hope, thus proving that the Atlantic and Indian Oceans are connected. In 1500, in his voyage to India following Vasco da Gama, Pedro Álvares Cabral reached Brazil, taken by the currents of the South Atlantic Gyre. Following these explorations, Spain and Portugal quickly conquered and colonized large territories in the New World and forced the Amerindian population into slavery in order to exploit the vast quantities of silver and gold they found. Spain and Portugal monopolized this trade in order to keep other European nations out, but conflicting interests nevertheless led to a series of Spanish-Portuguese wars. A peace treaty mediated by the Pope divided the conquered territories into Spanish and Portuguese sectors while keeping other colonial powers away. England, France, and the Dutch Republic enviously watched the Spanish and Portuguese wealth grow and allied themselves with pirates such as Henry Mainwaring and Alexandre Exquemelin. They could explore the convoys leaving the Americas because prevailing winds and currents made the transport of heavy metals slow and predictable.[79]

In the colonies of the Americas, depredation, smallpox and other diseases, and slavery quickly reduced the indigenous population of the Americas to the extent that the Atlantic slave trade was introduced by colonists to replace them – a trade that became the norm and an integral part of the colonization. Between the 15th century and 1888, when Brazil became the last part of the Americas to end the slave trade, an estimated 9.5 million enslaved Africans were shipped into the New World, most of them destined for agricultural labor. The slave trade was officially abolished in the British Empire and the United States in 1808, and slavery itself was abolished in the British Empire in 1838 and in the United States in 1865 after the Civil War.[80][81]

From Columbus to the Industrial Revolution trans-Atlantic trade, including colonialism and slavery, became crucial for Western Europe. For European countries with direct access to the Atlantic (including Britain, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain) 1500–1800 was a period of sustained growth during which these countries grew richer than those in Eastern Europe and Asia. Colonialism evolved as part of the trans-Atlantic trade, but this trade also strengthened the position of merchant groups at the expense of monarchs. Growth was more rapid in non-absolutist countries, such as Britain and the Netherlands, and more limited in absolutist monarchies, such as Portugal, Spain, and France, where profit mostly or exclusively benefited the monarchy and its allies.[82]

Trans-Atlantic trade also resulted in increasing urbanization: in European countries facing the Atlantic, urbanization grew from 8% in 1300, 10.1% in 1500, to 24.5% in 1850; in other European countries from 10% in 1300, 11.4% in 1500, to 17% in 1850. Likewise, GDP doubled in Atlantic countries but rose by only 30% in the rest of Europe. By the end of the 17th century, the volume of the Trans-Atlantic trade had surpassed that of the Mediterranean trade.[82]

Economy

[edit]

The Atlantic has contributed significantly to the development and economy of surrounding countries. Besides major transatlantic transportation and communication routes, the Atlantic offers abundant petroleum deposits in the sedimentary rocks of the continental shelves.[23] The Atlantic harbors petroleum and gas fields, fish, marine mammals (seals and whales), sand and gravel aggregates, placer deposits, polymetallic nodules, and precious stones.[83] Gold deposits are a mile or two underwater on the ocean floor, however, the deposits are also encased in rock that must be mined through. Currently, there is no cost-effective way to mine or extract gold from the ocean to make a profit.[84] Various international treaties attempt to reduce pollution caused by environmental threats such as oil spills, marine debris, and the incineration of toxic wastes at sea.[23]

Fisheries

[edit]The shelves of the Atlantic hosts one of the world's richest fishing resources. The most productive areas include the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, the Scotian Shelf, Georges Bank off Cape Cod, the Bahama Banks, the waters around Iceland, the Irish Sea, the Bay of Fundy, the Dogger Bank of the North Sea, and the Falkland Banks.[23] Fisheries have undergone significant changes since the 1950s and global catches can now be divided into three groups of which only two are observed in the Atlantic: fisheries in the eastern-central and southwest Atlantic oscillate around a globally stable value, the rest of the Atlantic is in overall decline following historical peaks. The third group, "continuously increasing trend since 1950", is only found in the Indian Ocean and western Pacific.[85] UN FAO partitioned the Atlantic into major fishing areas:

- Northeast Atlantic

Northeast Atlantic is schematically limited to the 40°00' west longitude (except around Greenland), south to the 36°00' north latitude, and to the 68°30' east longitude, with both the west and east longitude limits reaching to the north pole. The Atlantic's subareas include: Barents Sea; Norwegian Sea, Spitzbergen, and Bear Island; Skagerrak, Kattegat, Sound, Belt Sea, and Baltic Sea; North Sea; Iceland and Faroes Grounds; Rockall, Northwest Coast of Scotland, and North Ireland; Irish Sea, West of Ireland, Porcupine Bank, and eastern and western English Channel; Bay of Biscay; Portuguese Waters; Azores Grounds and Northeast Atlantic South; North of Azores; and East Greenland. There are also two defunct subareas.[86]

- In the Northeast Atlantic total catches decreased between the mid-1970s and the 1990s and reached 8.7 million tons in 2013. Blue whiting reached a 2.4 million tons peak in 2004 but was down to 628,000 tons in 2013. Recovery plans for cod, sole, and plaice have reduced mortality in these species. Arctic cod reached its lowest levels in the 1960s–1980s but is now recovered. Arctic saithe and haddock are considered fully fished; Sand eel is overfished as was capelin which has now recovered to fully fished. Limited data makes the state of redfishes and deep-water species difficult to assess but most likely they remain vulnerable to overfishing. Stocks of northern shrimp and Norwegian lobster are in good condition. In the Northeast Atlantic, 21% of stocks are considered overfished.[85]

- This zone makes almost three-quarters (72.8%) of European Union fishing catches in 2020. Main fishing EU countries are Denmark, France, the Netherlands and Spain. Most common species include herring, mackerel, and sprats.

- Northwest Atlantic

- In the Northwest Atlantic landings have decreased from 4.2 million tons in the early 1970s to 1.9 million tons in 2013. During the 21st century, some species have shown weak signs of recovery, including Greenland halibut, yellowtail flounder, Atlantic halibut, haddock, spiny dogfish, while other stocks shown no such signs, including cod, witch flounder, and redfish. Stocks of invertebrates, in contrast, remain at record levels of abundance. 31% of stocks are overfished in the northwest Atlantic.[85]

In 1497, John Cabot became the first Western European since the Vikings to explore mainland North America and one of his major discoveries was the abundant resources of Atlantic cod off Newfoundland. Referred to as "Newfoundland Currency" this discovery yielded some 200 million tons of fish over five centuries. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, new fisheries started to exploit haddock, mackerel, and lobster. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the introduction of European and Asian distant-water fleets in the area dramatically increased the fishing capacity and the number of exploited species. It also expanded the exploited areas from near-shore to the open sea and to great depths to include deep-water species such as redfish, Greenland halibut, witch flounder, and grenadiers. Overfishing in the area was recognized as early as the 1960s but, because this was occurring on international waters, it took until the late 1970s before any attempts to regulate was made. In the early 1990s, this finally resulted in the collapse of the Atlantic northwest cod fishery. The population of a number of deep-sea fishes also collapsed in the process, including American plaice, redfish, and Greenland halibut, together with flounder and grenadier.[87]

- Eastern central-Atlantic

- In the eastern central-Atlantic small pelagic fishes constitute about 50% of landings with sardine reaching 0.6–1.0 million tons per year. Pelagic fish stocks are considered fully fished or overfished, with sardines south of Cape Bojador the notable exception. Almost half of the stocks are fished at biologically unsustainable levels. Total catches have been fluctuating since the 1970s; reaching 3.9 million tons in 2013 or slightly less than the peak production in 2010.[85]

- Western central-Atlantic

- In the western central-Atlantic, catches have been decreasing since 2000 and reached 1.3 million tons in 2013. The most important species in the area, Gulf menhaden, reached a million tons in the mid-1980s but only half a million tons in 2013 and is now considered fully fished. Round sardinella was an important species in the 1990s but is now considered overfished. Groupers and snappers are overfished and northern brown shrimp and American cupped oyster are considered fully fished approaching overfished. 44% of stocks are being fished at unsustainable levels.[85]

- Southeast Atlantic

- In the southeast Atlantic catches have decreased from 3.3 million tons in the early 1970s to 1.3 million tons in 2013. Horse mackerel and hake are the most important species, together representing almost half of the landings. Off South Africa and Namibia deep-water hake and shallow-water Cape hake have recovered to sustainable levels since regulations were introduced in 2006 and the states of southern African pilchard and anchovy have improved to fully fished in 2013.[85]

- Southwest Atlantic

- In the southwest Atlantic, a peak was reached in the mid-1980s and catches now fluctuate between 1.7 and 2.6 million tons. The most important species, the Argentine shortfin squid, which reached half a million tons in 2013 or half the peak value, is considered fully fished to overfished. Another important species was the Brazilian sardinella, with a production of 100,000 tons in 2013 it is now considered overfished. Half the stocks in this area are being fished at unsustainable levels: Whitehead's round herring has not yet reached fully fished but Cunene horse mackerel is overfished. The sea snail perlemoen abalone is targeted by illegal fishing and remains overfished.[85]

Environmental issues

[edit]Endangered species

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2020) |

Endangered marine species include the manatee, seals, sea lions, turtles, and whales. Drift net fishing can kill dolphins, albatrosses and other seabirds (petrels, auks), hastening the fish stock decline and contributing to international disputes.[88]

Waste and pollution

[edit]Marine pollution is a generic term for the entry into the ocean of potentially hazardous chemicals or particles. The biggest culprits are rivers and with them many agriculture fertilizer chemicals as well as livestock and human waste. The excess of oxygen-depleting chemicals leads to hypoxia and the creation of a dead zone.[89]

Marine debris, which is also known as marine litter, describes human-created waste floating in a body of water. Oceanic debris tends to accumulate at the center of gyres and coastlines, frequently washing aground where it is known as beach litter. The North Atlantic garbage patch is estimated to be hundreds of kilometers across in size.[90]

Other pollution concerns include agricultural and municipal waste. Municipal pollution comes from the eastern United States, southern Brazil, and eastern Argentina; oil pollution in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Lake Maracaibo, Mediterranean Sea, and North Sea; and industrial waste and municipal sewage pollution in the Baltic Sea, North Sea, and Mediterranean Sea.

A USAF C-124 aircraft from Dover Air Force Base, Delaware was carrying three nuclear bombs over the Atlantic Ocean when it experienced a loss of power. For their own safety, the crew jettisoned two nuclear bombs, which were never recovered.[91]

Climate change

[edit]North Atlantic hurricane activity has increased over past decades because of increased sea surface temperature (SST) at tropical latitudes, changes that can be attributed to either the natural Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) or to anthropogenic climate change.[92] A 2005 report indicated that the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) slowed down by 30% between 1957 and 2004.[93] In 2024, the research highlighted a significant weakening of the AMOC by approximately 12% over the past two decades.[94] If the AMO were responsible for SST variability, the AMOC would have increased in strength, which is apparently not the case. Furthermore, it is clear from statistical analyses of annual tropical cyclones that these changes do not display multidecadal cyclicity.[92] Therefore, these changes in SST must be caused by human activities.[95]

The ocean mixed layer plays an important role in heat storage over seasonal and decadal time scales, whereas deeper layers are affected over millennia and have a heat capacity about 50 times that of the mixed layer. This heat uptake provides a time-lag for climate change but it also results in thermal expansion of the oceans which contributes to sea level rise. 21st-century global warming will probably result in an equilibrium sea-level rise five times greater than today, whilst melting of glaciers, including that of the Greenland ice sheet, expected to have virtually no effect during the 21st century, will likely result in a sea-level rise of 3–6 metres (9.8–19.7 ft) over a millennium.[96]

See also

[edit]- Atlantic Revolutions

- List of countries and territories bordering the Atlantic Ocean

- List of seas on Earth § Atlantic Ocean

- List of rivers of the Americas by coastline § Atlantic Ocean coast

- Seven Seas

- Shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean

- Atlantic hurricanes

- Piracy in the Atlantic World

- Transatlantic crossing

- South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone

- Natural delimitation between the Pacific and South Atlantic oceans by the Scotia Arc

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d CIA World Factbook: Atlantic Ocean

- ^ a b "Atlantic Ocean". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d Eakins & Sharman 2010

- ^ Dean, Josh (21 December 2018). "An inside look at the first solo trip to the deepest point of the Atlantic". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ SAS, Des Clics Nomades. "Water temperature of the Atlantic Ocean - real time map and monthly temperatures". SeaTemperatu.re. Retrieved 15 June 2025.

- ^ International Hydrographic Organization, Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd ed. (1953) Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, pages 4 and 13.

- ^ Mangas, Julio; Plácido, Domingo; Elícegui, Elvira Gangutia; Rodríguez Somolinos, Helena (1998). La Península Ibérica en los autores griegos: de Homero a Platón – SLG / (Sch. A. R. 1. 211). Editorial Complutense. p. 283.

- ^ "Ἀτλαντίς, DGE Diccionario Griego-Español". dge.cchs.csic.es. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018.

- ^ Hdt. 1.202.4

- ^ a b Oxford Dictionaries 2015

- ^ Janni 2015, p. 27

- ^ Ripley & Anderson Dana 1873

- ^ Steele, Ian Kenneth (1986). The English Atlantic, 1675–1740: An Exploration of Communication and Community. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-503968-9.

- ^ "pond". Oxford English and Spanish Dictionary, Synonyms, and Spanish to English Translator. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ "Pond". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Wellington, Nehemiah (1 January 1869). Historical Notices of Events Occurring Chiefly in the Reign of Charles I. London: Richard Bentley.

- ^ Brown, Laurence (8 April 2018). Lost in The Pond (Digital video). Archived from the original on 22 November 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b IHO 1953

- ^ CIA World Factbook: Pacific Ocean

- ^ USGS: Mapping Puerto Rico Trench

- ^ "Atlantic Ocean". Five Deeps Expedition. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b c World Heritage Centre: Mid-Atlantic Ridge

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l U.S. Navy 2001

- ^ a b c Levin & Gooday 2003, Seafloor topography and physiography, pp. 113–114

- ^ The Geological Society: Mid-Atlantic Ridge

- ^ Kenneth J. Hsü (1987). The Mediterranean Was a Desert: A Voyage of the Glomar Challenger. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02406-6.

- ^ DeMets, Gordon & Argus 2010, The Azores microplate, pp. 24–25

- ^ DeMets, Gordon & Argus 2010, Boundary between the North and South America plates, pp. 26–27

- ^ Thomson 1877, p. 290

- ^ NOAA: Timeline

- ^ Hamilton-Paterson, James (1992). The Great Deep.

- ^ Marsh et al. 2007, Introduction, p. 1

- ^ Emery & Meincke 1986, Table, p. 385

- ^ a b Emery & Meincke 1986, Atlantic Ocean, pp. 384–386

- ^ Smethie et al. 2000, Formation of NADW, pp. 14299–14300

- ^ Smethie et al. 2000, Introduction, p. 14297

- ^ Marchal, Waelbroeck & Colin de Verdière 2016, Introduction, pp. 1545–1547

- ^ Tréguier et al. 2005, Introduction, p. 757

- ^ Böning et al. 2006, Introduction, p. 1; Fig. 2, p. 2

- ^ Stramma & England 1999, Abstract

- ^ Gordon & Bosley 1991, Abstract

- ^ a b Lüning 1990, pp. 223–225

- ^ Jerzmańska & Kotlarczyk 1976, Abstract; Biogeographic Significance of the "Quasi-Sargasso" Assemblage, pp. 303–304

- ^ Als et al. 2011, p. 1334

- ^ Marks, Andrea (17 April 2017). "Do Baby Eels Use Magnetic Maps to Hitch a Ride on the Gulf Stream?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "About International Ice Patrol (IIP)". U. S. Coast Guard Navigation Center. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021.

- ^ Landsea, Chris (13 July 2005). "Why doesn't the South Atlantic Ocean experience tropical cyclones?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ Fitton, Godfrey; Larsen, Lotte Melchior (1999). "The geological history of the North Atlantic Ocean". pp. 10, 15 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Emery, K. O. (1962). "Atlantic Continental Shelf and Slope of the United States – Geologic Background" (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Seton et al. 2012, Central Atlantic, pp. 218, 220

- ^ Blackburn et al. 2013, p. 941

- ^ Marzoli et al. 1999, p. 616

- ^ Lessios 2008, Abstract, Introduction, p. 64

- ^ Seton et al. 2012, Northern Atlantic, p. 220

- ^ Fitton & Larsen 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Fitton & Larsen 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Fitton & Larsen 1999, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Gubbay S. 2003. Seamounts of the northeast Atlantic. OASIS (Oceanic Seamounts: an Integrated Study). Hamburg & WWF, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- ^ a b Eagles 2007, Introduction, p. 353

- ^ Bullard, Everett & Smith 1965

- ^ a b c d Seton et al. 2012, South Atlantic, pp. 217–218

- ^ a b Torsvik et al. 2009, General setting and magmatism, pp. 1316–1318

- ^ Giorgioni, Martino; Weissert, Helmut; Bernasconi, Stefano M.; Hochuli, Peter A.; Keller, Christina E.; Coccioni, Rodolfo; Petrizzo, Maria Rose; Lukeneder, Alexander; Garcia, Therese I. (March 2015). "Paleoceanographic changes during the Albian–Cenomanian in the Tethys and North Atlantic and the onset of the Cretaceous chalk". Global and Planetary Change. 126: 46–61. Bibcode:2015GPC...126...46G. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2015.01.005. ISSN 0921-8181. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ De A. Carvalho, Marcelo; Bengtson, Peter; Lana, Cecília C. (23 November 2015). "Late Aptian (Cretaceous) paleoceanography of the South Atlantic Ocean inferred from dinocyst communities of the Sergipe Basin, Brazil". Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 31 (1): 2–26. doi:10.1002/2014PA002772.

- ^ Livermore et al. 2005, Abstract

- ^ Duarte et al. 2013, Abstract; Conclusions, p. 842

- ^ Mellars 2006, Abstract

- ^ Riede 2014, pp. 1–2

- ^ Bjerck 2009, Introduction, pp. 118–119

- ^ Avery et al. 2008, Introduction, p. 66

- ^ Bailey & Flemming 2008, The Long-Term History of Marine Resources, pp. 4–5

- ^ Martin 1973, Abstract

- ^ Greenberg, Turner & Zegura 1986

- ^ O'Rourke & Raff 2010, Introduction, p. 202

- ^ O'Rourke & Raff 2010, Conclusions and Outlook, p. 206

- ^ O'Rourke & Raff 2010, Beringian Scenarios, pp. 205–206

- ^ Dugmore, Keller & McGovern 2007, Introduction, pp. 12–13; The Norse in The North Atlantic, pp. 13–14

- ^ Patterson et al. 2010, pp. 5308–5309

- ^ a b Chambliss 1989, Piracy, pp. 184–188

- ^ Lovejoy 1982, Abstract

- ^ Bravo 2007, The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, pp. 213–215

- ^ a b Acemoglu, Johnson & Robinson 2005, Abstract; pp. 546–551

- ^ Kubesh, K.; McNeil, N.; Bellotto, K. (2008). Ocean Habitats. In the Hands of a Child. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Administration, US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric. "Is there gold in the ocean?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g FOA 2016, pp. 39–41

- ^ "FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture". fao.org. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ FAO 2011, pp. 22–23

- ^ Eisenbud, R. (1985). "Problems and Prospects for the Pelagic Driftnet". Michigan State University, Animal Legal & Historical Center. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Sebastian A. Gerlach "Marine Pollution", Springer, Berlin (1975)

- ^ "Huge Garbage Patch Found in Atlantic Too". National Geographic. 2 March 2010. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019.

- ^ HR Lease (March 1986). "DoD Mishaps" (PDF). Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2008.

- ^ a b Mann & Emanuel 2006, pp. 233–241

- ^ Bryden, Longworth & Cunningham 2005, Abstract

- ^ Marine, Rosenstiel School of; Atmospheric; Science, Earth. "Warming of Antarctic deep-sea waters contribute to sea level rise in North Atlantic, study finds". phys.org. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Webster et al. 2005

- ^ Bigg et al. 2003, Sea-level change, pp. 1128–1129

Sources

[edit]- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J. (2005). "The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change and economic growth" (PDF). The American Economic Review. 95 (3): 546–579. doi:10.1257/0002828054201305. hdl:1721.1/64034. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- Als, T.D.; Hansen, M.M.; Maes, G.E.; Castonguay, M.; Riemann, L.; Aarestrup, K.I.M.; Munk, P.; Sparholt, H.; Hanel, R.; Bernatchez, L. (2011). "All roads lead to home: panmixia of European eel in the Sargasso Sea" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 20 (7): 1333–1346. Bibcode:2011MolEc..20.1333A. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05011.x. PMID 21299662. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Avery, G.; Halkett, D.; Orton, J.; Steele, T.; Tusenius, M.; Klein, R. (2008). "The Ysterfontein 1 Middle Stone Age rock shelter and the evolution of coastal foraging". Goodwin Series. 10: 66–89. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Bailey, G N.; Flemming, N.C. (2008). "Archaeology of the continental shelf: marine resources, submerged landscapes and underwater archaeology" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 27 (23): 2153–2165. Bibcode:2008QSRv...27.2153B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.08.012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Bigg, G.R.; Jickells, T.D.; Liss, P.S.; Osborn, T.J. (2003). "The role of the oceans in climate". International Journal of Climatology. 23 (10): 1127–1159. Bibcode:2003IJCli..23.1127B. doi:10.1002/joc.926. S2CID 128837630. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Bjerck, H.B. (2009). "Colonizing seascapes: comparative perspectives on the development of maritime relations in Scandinavia and Patagonia". Arctic Anthropology. 46 (1–2): 118–131. doi:10.1353/arc.0.0019. S2CID 128404669. [permanent dead link]

- Blackburn, T.J.; Olsen, P.E.; Bowring, S.A.; McLean, N.M.; Kent, D.V.; Puffer, J.; McHone, G.; Rasbury, T.; Et-Touhami, M. (2013). "Zircon U-Pb geochronology links the end-Triassic extinction with the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province" (PDF). Science. 340 (6135): 941–945. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..941B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1019.4042. doi:10.1126/science.1234204. PMID 23519213. S2CID 15895416. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Böning, C.W.; Scheinert, M.; Dengg, J.; Biastoch, A.; Funk, A. (2006). "Decadal variability of subpolar gyre transport and its reverberation in the North Atlantic overturning". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (21): L21S01. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..3321S01B. doi:10.1029/2006GL026906. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Bravo, K.E. (2007). "Exploring the analogy between modern trafficking in humans and the trans-Atlantic slave trade" (PDF). Boston University International Law Journal. 25 (207). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- Bryden, H.L.; Longworth, H.R.; Cunningham, S.A. (2005). "Slowing of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation at 25 N" (PDF). Nature. 438 (7068): 655–657. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..655B. doi:10.1038/nature04385. PMID 16319889. S2CID 4429828. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- Bullard, E.; Everett, J.E.; Smith, A.G. (1965). "The fit of the continents around the Atlantic" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 258 (1088): 41–51. Bibcode:1965RSPTA.258...41B. doi:10.1098/rsta.1965.0020. PMID 17801943. S2CID 27169876. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Chambliss, W.J. (1989). "State-organized crime" (PDF). Criminology. 27 (2): 183–208. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1989.tb01028.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "Atlantic Ocean". CIA World Factbook. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "Pacific Ocean". CIA World Factbook. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- DeMets, C.; Gordon, R.G.; Argus, D.F. (2010). "Geologically current plate motions". Geophysical Journal International. 181 (1): 1–80. Bibcode:2010GeoJI.181....1D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04491.x.

- Duarte, J.C.; Rosas, F.M.; Terrinha, P.; Schellart, W.P.; Boutelier, D.; Gutscher, M.A.; Ribeiro, A. (2013). "Are subduction zones invading the Atlantic? Evidence from the southwest Iberia margin". Geology. 41 (8): 839–842. Bibcode:2013Geo....41..839D. doi:10.1130/G34100.1.

- Dugmore, A.J.; Keller, C.; McGovern, T.H. (2007). "Norse Greenland settlement: reflections on climate change, trade, and the contrasting fates of human settlements in the North Atlantic islands" (PDF). Arctic Anthropology. 44 (1): 12–36. doi:10.1353/arc.2011.0038. PMID 21847839. S2CID 10030083. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- Eagles, G. (2007). "New angles on South Atlantic opening". Geophysical Journal International. 168 (1): 353–361. Bibcode:2007GeoJI.168..353E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2006.03206.x. S2CID 29158845.

- Eakins, B.W.; Sharman, G.F. (2010). "Volumes of the World's Oceans from ETOPO1". Boulder, CO: NOAA National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Emery, W.J.; Meincke, J. (1986). "Global water masses-summary and review" (PDF). Oceanologica Acta. 9 (4): 383–391 (PDF pages scrambled). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (PDF) (Report). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FOA). 2016. ISBN 978-92-5-109185-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Mid-Atlantic Ridge". The Geological Society. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- Greenberg, J.H.; Turner, C.G.; Zegura, S.L. (1986). "The settlement of the Americas: A comparison of the linguistic, dental and genetic evidence". Current Anthropology. 27 (5): 477–497. doi:10.1086/203472. JSTOR 2742857. S2CID 144209907.

- Gordon, A.L.; Bosley, K.T. (1991). "Cyclonic gyre in the tropical South Atlantic" (PDF). Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers. 38: S323 – S343. Bibcode:1991DSRA...38S.323G. doi:10.1016/S0198-0149(12)80015-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Henshilwood, C.S.; d'Errico, F.; Yates, R.; Jacobs, Z.; Tribolo, C.; Duller, G.A.; Mercier, N.; Sealy, J.C.; Valladas, H.; Watts, I.; Wintle, A.G. (2002). "Emergence of modern human behavior: Middle Stone Age engravings from South Africa" (PDF). Science. 295 (5558): 1278–1280. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1278H. doi:10.1126/science.1067575. PMID 11786608. S2CID 31169551. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Herodotus. "Perseus Under Philologic: Hdt. 1.202.4". University of Chicago. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas" (PDF). Special Publication. 23 (4376): 484. 1953. Bibcode:1953Natur.172R.484.. doi:10.1038/172484b0. S2CID 36029611. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2020. map

- Janni, P. (2015). "The Sea of the Greeks and Romans". In Bianchetti, S.; Cataudella, M.; Gehrke, H.-J. (eds.). Brill's Companion to Ancient Geography: The Inhabited World in Greek and Roman Tradition. Brill. pp. 21–42. doi:10.1163/9789004284715_003. ISBN 978-90-04-28471-5. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Jerzmańska, A.; Kotlarczyk, J. (1976). "The beginnings of the Sargasso assemblage in the Tethys?". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 20 (4): 297–306. Bibcode:1976PPP....20..297J. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(76)90009-2. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Kulka, D. (2011). "B1. Northwest Atlantic" (PDF). Review of the state of world marine fishery resources. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper (Report). Vol. 569. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). p. 334. ISBN 978-92-5-107023-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- Lessios, H.A. (2008). "The great American schism: divergence of marine organisms after the rise of the Central American Isthmus" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 39: 63–91. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095815. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Levin, L.A.; Gooday, A.J. (2003). "The Deep Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). In Tyler, P.A. (ed.). Ecosystems of the World. Ecosystems of the deep oceans. Vol. 28. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. pp. 111–178. ISBN 978-0-444-82619-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Livermore, R.; Nankivell, A.; Eagles, G.; Morris, P. (2005). "Paleogene opening of Drake passage" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 236 (1): 459–470. Bibcode:2005E&PSL.236..459L. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.03.027. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Lovejoy, P.E. (1982). "The volume of the Atlantic slave trade: A synthesis". The Journal of African History. 23 (4): 473–501. doi:10.1017/S0021853700021319. S2CID 155078187.

- Lüning, K. (1990). "Sargasso Sea". In Yarish, C.; Kirkman, H. (eds.). Seaweeds: Their Environment, Biogeography, and Ecophysiology. Vol. 36. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 222–225. Bibcode:1991LimOc..36.1066M. doi:10.4319/lo.1991.36.5.1066. ISBN 978-0-471-62434-9. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Mann, M.E.; Emanuel, K.A. (2006). "Atlantic hurricane trends linked to climate change". Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 87 (24): 233–241. Bibcode:2006EOSTr..87..233M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.174.4349. doi:10.1029/2006eo240001.

- Marchal, O.; Waelbroeck, C.; Colin de Verdière, A. (2016). "On the Movements of the North Atlantic Subpolar Front in the Preinstrumental Past" (PDF). Journal of Climate. 29 (4): 1545–1571. Bibcode:2016JCli...29.1545M. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0509.1. hdl:1912/7903. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Marean, C.W. (2011). "Coastal South Africa and the Coevolution of the Modern Human Lineage and the Coastal Adaptation" (PDF). In Bicho, N.F.; Haws, J.A.; Davis, L.G. (eds.). Trekking the Shore: Changing Coastlines and the Antiquity of Coastal Settlement. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Springer. pp. 421–440. ISBN 978-1-4419-8219-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Marean, C.W.; Cawthra, H.C.; Cowling, R.M.; Esler, K.J.; Fisher, E.; Milewski, A.; Potts, A.J.; Singels, E.; De Vynck, J. (2014). "Stone age people in a changing South African greater Cape Floristic Region". In Allsopp, N.; Colville, J.F.; Verboom, G.A. (eds.). Fynbos: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region, 164. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967958-4. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Marsh, R.; Hazeleger, W.; Yool, A.; Rohling, E.J. (2007). "Stability of the thermohaline circulation under millennial CO2 forcing and two alternative controls on Atlantic salinity". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (3): L03605. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..34.3605M. doi:10.1029/2006GL027815.

- Martin, P.S. (1973). "The Discovery of America: The first Americans may have swept the Western Hemisphere and decimated its fauna within 1000 years" (PDF). Science. 179 (4077): 969–974. Bibcode:1973Sci...179..969M. doi:10.1126/science.179.4077.969. PMID 17842155. S2CID 10395314. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Marzoli, A.; Renne, P.R.; Piccirillo, E.M.; Ernesto, M.; Bellieni, G.; De Min, A. (1999). "Extensive 200-million-year-old continental flood basalts of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province". Science. 284 (5414): 616–618. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..616M. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.616. PMID 10213679. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Mellars, P. (2006). "Why did modern human populations disperse from Africa ca. 60,000 years ago? A new model" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (25): 9381–9386. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.9381M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510792103. PMC 1480416. PMID 16772383. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "History of NOAA Ocean Exploration: Timeline". NOAA. 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- O'Rourke, D.H.; Raff, J.A. (2010). "The human genetic history of the Americas: the final frontier". Current Biology. 20 (4): R202 – R207. Bibcode:2010CBio...20.R202O. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.051. PMID 20178768. S2CID 14479088. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Patterson, W.P.; Dietrich, K.A.; Holmden, C.; Andrews, J.T. (2010). "Two millennia of North Atlantic seasonality and implications for Norse colonies" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (12): 5306–5310. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5306P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902522107. PMC 2851789. PMID 20212157. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Riede, F. (2014). "The resettlement of northern Europe". In Cummings, V.; Jordan, P.; Zvelebil, M. (eds.). Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199551224.013.059. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Ripley, G.; Anderson Dana, C. (1873). The American cyclopaedia: a popular dictionary of general knowledge. Appleton. pp. 69–. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- Seton, M.; Müller, R.D.; Zahirovic, S.; Gaina, C.; Torsvik, T.; Shephard, G.; Talsma, A.; Gurnis, M.; Maus, S.; Chandler, M. (2012). "Global continental and ocean basin reconstructions since 200Ma". Earth-Science Reviews. 113 (3): 212–270. Bibcode:2012ESRv..113..212S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.03.002. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Smethie, W.M.; Fine, R.A.; Putzka, A.; Jones, E.P. (2000). "Tracing the flow of North Atlantic Deep Water using chlorofluorocarbons". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 105 (C6): 14297–14323. Bibcode:2000JGR...10514297S. doi:10.1029/1999JC900274.

- Stramma, L.; England, M. (1999). "On the water masses and mean circulation of the South Atlantic Ocean". Journal of Geophysical Research. 104 (C9): 20863–20883. Bibcode:1999JGR...10420863S. doi:10.1029/1999JC900139.

- Thomas, S. (8 June 2015). "How the oceans got their names". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Thomson, W. (1877). The Voyage of the 'Challenger.' The Atlantic: A Preliminary Account of the General Results of the Exploring Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Year 1873 and the Early Part of the Year 1876 (PDF, 384 MB). London: Macmillan. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Torsvik, T.H.; Rousse, S.; Labails, C.; Smethurst, M.A. (2009). "A new scheme for the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean and the dissection of an Aptian salt basin". Geophysical Journal International. 177 (3): 1315–1333. Bibcode:2009GeoJI.177.1315T. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04137.x.

- Tréguier, A.M.; Theetten, S.; Chassignet, E.P.; Penduff, T.; Smith, R.; Talley, L.; Beismann, J.O.; Böning, C. (2005). "The North Atlantic subpolar gyre in four high-resolution models". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 35 (5): 757–774. Bibcode:2005JPO....35..757T. doi:10.1175/JPO2720.1.

- "Mapping of the Puerto Rico Trench, the Deepest Part of the Atlantic, is Nearing Completion". United States Geological Survey. October 2003. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Atlantic Ocean Facts". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 2 March 2001. Retrieved 12 November 2001.

- Webster, P.J.; Holland, G.J.; Curry, J.A.; Chang, H.R. (2005). "Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment". Science. 309 (5742): 1844–1846. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.1844W. doi:10.1126/science.1116448. PMID 16166514. S2CID 35666312.

- "The Mid-Atlantic Ridge". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2007–2008. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Dickson, Henry Newton (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). pp. 855–857.

- Winchester, Simon (2010). Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories. HarperCollins UK. ISBN 978-0-00-734137-5.

External links

[edit]- Atlantic Ocean. Cartage.org.lb (archived)

- "Map of Atlantic Coast of North America from the Chesapeake Bay to Florida" from 1639 via the Library of Congress