Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Petroleum industry

View on Wikipedia

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry, includes the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transportation (often by oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing of petroleum products. The largest volume products of the industry are fuel oil and gasoline (petrol). Petroleum is also the raw material for many chemical products, including pharmaceuticals, solvents, fertilizers, pesticides, synthetic fragrances, and plastics. The industry is usually divided into three major components: upstream, midstream, and downstream. Upstream regards exploration and extraction of crude oil, midstream encompasses transportation and storage of it, and downstream concerns refining crude oil into various end products.

Petroleum is vital to many industries, and is necessary for the maintenance of industrial civilization in its current configuration, making it a critical concern for many nations. Oil accounts for a large percentage of the world's energy consumption, ranging from a low of 32% for Europe and Asia, to a high of 53% for the Middle East.

Other geographic regions' consumption patterns are as follows: South and Central America (44%), Africa (41%), and North America (40%). The world consumes 36 billion barrels (5.8 km3) of oil per year,[1] with developed nations being the largest consumers. The United States consumed 18% of the oil produced in 2015.[2] The production, distribution, refining, and retailing of petroleum taken as a whole represents the world's largest industry in terms of dollar value.

History

[edit]

Prehistory

[edit]

Petroleum is a naturally occurring liquid found in rock formations. It consists of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights, plus other organic compounds. It is generally accepted that oil is formed mostly from the carbon rich remains of ancient plankton after exposure to heat and pressure in Earth's crust over hundreds of millions of years. Over time, the decayed residue was covered by layers of mud and silt, sinking further down into Earth's crust and preserved there between hot and pressured layers, gradually transforming into oil reservoirs.[3]

Early history

[edit]Petroleum in an unrefined state has been utilized by humans for over 5000 years. Oil in general has been used since early human history to keep fires ablaze and in warfare.

Its importance to the world economy however, evolved slowly, with whale oil being used for lighting in the 19th century and wood and coal used for heating and cooking well into the 20th century. Even though the Industrial Revolution generated an increasing need for energy, this was initially met mainly by coal, and from other sources including whale oil. However, when it was discovered that kerosene could be extracted from crude oil and used as a lighting and heating fuel, the demand for petroleum increased greatly, and by the early twentieth century had become the most valuable commodity traded on world markets.[4]

Modern history

[edit]

This graph was using the legacy Graph extension, which is no longer supported. It needs to be converted to the new Chart extension. |

Imperial Russia produced 3,500 tons of oil in 1825 and doubled its output by mid-century.[8] After oil drilling began in the region of present-day Azerbaijan in 1846, in Baku, the Russian Empire built two large pipelines: the 833 km long pipeline to transport oil from the Caspian to the Black Sea port of Batum (Baku-Batum pipeline), completed in 1906, and the 162 km long pipeline to carry oil from Chechnya to the Caspian. The first drilled oil wells in Baku were built in 1871–1872 by Ivan Mirzoev, an Armenian businessman who is referred to as one of the 'founding fathers' of Baku's oil industry.[9][10]

At the turn of the 20th century, Imperial Russia's output of oil, almost entirely from the Apsheron Peninsula, accounted for half of the world's production and dominated international markets.[11] Nearly 200 small refineries operated in the suburbs of Baku by 1884.[12] As a side effect of these early developments, the Apsheron Peninsula emerged as the world's "oldest legacy of oil pollution and environmental negligence".[13] In 1846 Baku (Bibi-Heybat settlement) featured the first ever well drilled with percussion tools to a depth of 21 meters for oil exploration. In 1878 Ludvig Nobel and his Branobel company "revolutionized oil transport" by commissioning the first oil tanker and launching it on the Caspian Sea.[11]

Samuel Kier established America's first oil refinery in Pittsburgh on Seventh avenue near Grant Street in 1853. Ignacy Łukasiewicz built one of the first modern oil-refineries near Jasło (then in the Austrian dependent Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria in Central European Galicia), present-day Poland, in 1854–56.[14] Galician refineries were initially small, as demand for refined fuel was limited. The refined products were used in artificial asphalt, machine oil and lubricants, in addition to Łukasiewicz's kerosene lamp. As kerosene lamps gained popularity, the refining industry grew in the area.

The first commercial oil-well in Canada became operational in 1858 at Oil Springs, Ontario (then Canada West).[15] Businessman James Miller Williams dug several wells between 1855 and 1858 before discovering a rich reserve of oil four metres below ground.[16][17] Williams extracted 1.5 million litres of crude oil by 1860, refining much of it into kerosene-lamp oil.[15] Some historians challenge Canada's claim to North America's first oil field, arguing that Pennsylvania's famous Drake Well was the continent's first. But there is evidence to support Williams, not least of which is that the Drake well did not come into production until August 28, 1859. The controversial point might be that Williams found oil above bedrock while Edwin Drake's well located oil within a bedrock reservoir. The discovery at Oil Springs touched off an oil boom which brought hundreds of speculators and workers to the area. Canada's first gusher (flowing well) erupted on January 16, 1862, when local oil-man John Shaw struck oil at 158 feet (48 m).[18] For a week the oil gushed unchecked at levels reported as high as 3,000 barrels per day.

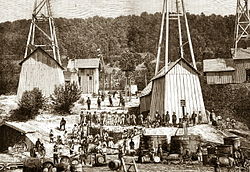

The first modern oil-drilling in the United States began in West Virginia and Pennsylvania in the 1850s. Edwin Drake's 1859 well near Titusville, Pennsylvania, typically considered[by whom?] the first true[citation needed] modern[citation needed] oil well, touched off a major boom.[19][20][21][need quotation to verify] In the first quarter of the 20th century, the United States overtook Russia as the world's largest oil producer. By the 1920s, oil fields had been established in many countries including Canada, Poland, Sweden, Ukraine, the United States, Peru and Venezuela.[21]

The first successful oil tanker, the Zoroaster, was built in 1878 in Sweden, designed by Ludvig Nobel. It operated from Baku to Astrakhan.[22] A number of new tanker designs developed in the 1880s.[23]

In the early 1930s the Texas Company developed the first mobile steel barges for drilling in the brackish coastal areas of the Gulf of Mexico. In 1937 Pure Oil Company (now part of Chevron Corporation) and its partner Superior Oil Company (now part of ExxonMobil Corporation) used a fixed platform to develop a field in 14 feet (4.3 m) of water, one mile (1.6 km) offshore of Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana. In early 1947 Superior Oil erected a drilling/production oil-platform in 20 ft (6.1 m) of water some 18 miles[vague] off Vermilion Parish, Louisiana. Kerr-McGee Oil Industries, as operator for partners Phillips Petroleum (ConocoPhillips) and Stanolind Oil & Gas (BP), completed its historic Ship Shoal Block 32 well in November 1947, months before Superior actually drilled a discovery from their Vermilion platform farther offshore. In any case, that made Kerr-McGee's Gulf of Mexico well, Kermac No. 16, the first oil discovery drilled out of sight of land.[24][page needed][25] Forty-four Gulf of Mexico exploratory wells discovered 11 oil and natural gas fields by the end of 1949.[26]

During World War II (1939–1945) control of oil supply from Romania, Baku, the Middle East and the Dutch East Indies played a huge role in the events of the war and the ultimate victory of the Allies. The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran (1941) secured Allied control of oil-production in the Middle East. The expansion of Imperial Japan to the south aimed largely at accessing the oil-fields of the Dutch East Indies. Germany, cut off from sea-borne oil supplies by Allied blockade, failed in Operation Edelweiss to secure the Caucasus oil-fields for the Axis military in 1942, while Romania deprived the Wehrmacht of access to Ploesti oilfields – the largest in Europe – from August 1944. Cutting off the East Indies oil-supply (especially via submarine campaigns) considerably weakened Japan in the latter part of the war. After World War II ended in 1945, the countries of the Middle East took the lead in oil production from the United States. Important developments since World War II include deep-water drilling, the introduction of the drillship, and the growth of a global shipping network for petroleum – relying upon oil tankers and pipelines. In 1949 the first offshore oil-drilling at Oil Rocks (Neft Dashlari) in the Caspian Sea off Azerbaijan eventually resulted in a city built on pylons. In the 1960s and 1970s, multi-governmental organizations of oil–producing nations – OPEC and OAPEC – played a major role in setting petroleum prices and policy. Oil spills and their cleanup have become an issue of increasing political, environmental, and economic importance. New fields of hydrocarbon production developed in places such as Siberia, Sakhalin, Venezuela and North and West Africa.[citation needed]

With the advent of hydraulic fracturing and other horizontal drilling techniques, shale play has seen an enormous uptick in production. Areas of shale such as the Permian Basin and Eagle-Ford have become huge hotbeds of production for the largest oil corporations in the United States.[27]

Structure

[edit]

The American Petroleum Institute divides the petroleum industry into five sectors:[28]

- upstream (exploration, development and production of crude oil or natural gas)

- downstream (oil tankers, refiners, retailers and consumers)

- pipeline

- marine

- service and supply

Upstream

[edit]Oil companies used to be classified by sales as "supermajors" (BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, Shell, Eni and TotalEnergies), "majors", and "independents" or "jobbers". In recent years however, National Oil Companies (NOC, as opposed to IOC, International Oil Companies) have come to control the rights over the largest oil reserves; by this measure the top ten companies all are NOC. The following table shows the ten largest national oil companies ranked by reserves[29][30] and by production in 2012.[31]

| Rank | Company (Reserves) | Worldwide Liquids Reserves (109 bbl) | Worldwide Natural Gas Reserves (1012 ft3) | Total Reserves in Oil Equivalent Barrels (109 bbl) | Company (Production) | Output (Millions bbl/day)[1] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 260 | 254 | 303 | 12.5 | |||

| 2 | 138 | 948 | 300 | 6.4 | |||

| 3 | 15 | 905 | 170 | 5.3 | |||

| 4 | 116 | 120 | 134 | 4.4 | |||

| 5 | 99 | 171 | 129 | 4.1 | |||

| 6 | 92 | 199 | 126 | 3.9 | |||

| 7 | 102 | 56 | 111 | 3.6 | |||

| 8 | 36 | 184 | 68 | 3.5 | |||

| 9 | 41 | 50 | 50 | 3.2 | |||

| 10 | 12 | 159 | 39 | 2.9 | |||

| ^1 : Total energy output, including natural gas (converted to bbl of oil) for companies producing both. | |||||||

Most upstream work in the oil field or on an oil well is contracted out to drilling contractors and oil field service companies.[citation needed]

Aside from the NOCs which dominate the Upstream sector, there are many international companies that have a market share. For example:[32]

- BG Group

- BHP

- ConocoPhillips

- Chevron

- Eni

- ExxonMobil

- First Texas Energy Corporation

- Hess

- Marathon Oil

- OMV

- TotalEnergies

- Tullow Oil

- Rosneft

Midstream

[edit]Midstream operations are sometimes classified within the downstream sector, but these operations compose a separate and discrete sector of the petroleum industry. Midstream operations and processes include the following:

- Gathering: The gathering process employs narrow, low-pressure pipelines to connect oil- and gas-producing wells to larger, long-haul pipelines or processing facilities.[33]

- Processing/refining: Processing and refining operations turn crude oil and gas into marketable products. In the case of crude oil, these products include heating oil, gasoline for use in vehicles, jet fuel, and diesel oil.[34] Oil refining processes include distillation, vacuum distillation, catalytic reforming, catalytic cracking, alkylation, isomerization and hydrotreating.[34] Natural gas processing includes compression; glycol dehydration; amine treating; separating the product into pipeline-quality natural gas and a stream of mixed natural gas liquids; and fractionation, which separates the stream of mixed natural gas liquids into its components. The fractionation process yields ethane, propane, butane, isobutane, and natural gasoline.

- Transportation: Oil and gas are transported to processing facilities, and from there to end users, by pipeline, tanker/barge, truck, and rail. Pipelines are the most economical transportation method and are most suited to movement across longer distances, for example, across continents.[35] Tankers and barges are also employed for long-distance, often international transport. Rail and truck can also be used for longer distances but are most cost-effective for shorter routes.

- Storage: Midstream service providers provide storage facilities at terminals throughout the oil and gas distribution systems. These facilities are most often located near refining and processing facilities and are connected to pipeline systems to facilitate shipment when product demand must be met. While petroleum products are held in storage tanks, natural gas tends to be stored in underground facilities, such as salt dome caverns and depleted reservoirs.

- Technological applications: Midstream service providers apply technological solutions to improve efficiency during midstream processes. Technology can be used during compression of fuels to ease flow through pipelines; to better detect leaks in pipelines; and to automate communications for better pipeline and equipment monitoring.

While some upstream companies carry out certain midstream operations, the midstream sector is dominated by a number of companies that specialize in these services. Midstream companies include:

- Aux Sable

- Bridger Group

- DCP Midstream Partners

- Enbridge Energy Partners

- Enterprise Products Partners

- Genesis Energy

- Gibson Energy

- Inergy Midstream

- Kinder Morgan Energy Partners

- Oneok Partners

- Plains All American

- Sunoco Logistics

- Targa Midstream Services

- Targray Natural Gas Liquids

- TransCanada

- Williams Companies

- Petrolink

Social impact

[edit]The oil and gas industry spends only 0.4% of its net sales on research & development (R&D) which is in comparison with a range of other industries the lowest share.[36] Governments such as the United States government provide a heavy public subsidy to petroleum companies, with major tax breaks at various stages of oil exploration and extraction, including the costs of oil field leases and drilling equipment.[37] In recent years, enhanced oil recovery techniques – most notably multi-stage drilling and hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") – have moved to the forefront of the industry as this new technology plays a crucial and controversial role in new methods of oil extraction.[38]

Environmental impact

[edit]Water pollution

[edit]Some petroleum industry operations have been responsible for water pollution through by-products of refining and oil spills. Though hydraulic fracturing has significantly increased natural gas extraction, there is some belief and evidence to support that consumable water has seen increased in methane contamination due to this gas extraction.[39] Leaks from underground tanks and abandoned refineries may also contaminate groundwater in surrounding areas. Hydrocarbons that comprise refined petroleum are resistant to biodegradation and have been found to remain present in contaminated soils for years.[40] To hasten this process, bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon pollutants is often employed by means of aerobic degradation.[41] More recently, other bioremediative methods have been explored such as phytoremediation and thermal remediation.[42][43]

Air pollution

[edit]The industry is the largest industrial source of emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), a group of chemicals that contribute to the formation of ground-level ozone (smog).[44] The combustion of fossil fuels produces greenhouse gases and other air pollutants as by-products. Pollutants include nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide, volatile organic compounds and heavy metals.

Researchers have discovered that the petrochemical industry can produce ground-level ozone pollution at higher amounts in winter than in summer.[45]

Climate change

[edit]Greenhouse gases caused by burning fossil fuels drive climate change. In 1959, at a symposium organised by the American Petroleum Institute for the centennial of the American oil industry, the physicist Edward Teller warned of the danger of global climate change.[46] Edward Teller explained that carbon dioxide "in the atmosphere causes a greenhouse effect" and that burning more fossil fuels could "melt the icecaps and submerge New York".[46]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, founded by the United Nations in 1988, concludes that human-sourced greenhouse gases are responsible for most of the observed temperature increase since the middle of the twentieth century.

As a result of climate change concerns, many people have begun using other methods of energy such as solar and wind. This recent shift has some petroleum enthusiasts skeptical about the future of the industry.[47]

See also

[edit]- Industry pioneers

- Faustino Piaggio, an early oil industry pioneer

- Oil production

- Corrosion inhibitors for petroleum industry

- Peak oil

- Oil terminal

- Oil supplies

- Integrated operations

- Instrumentation in petrochemical industries

- Standardization in oil industry

- ISO/TC 67

- List of crude oil products

- Financial and political

- List of oil exploration and production companies

- List of largest oil and gas companies by revenue

- Chronology of world oil market events (1970–2005)

- Energy crisis: 1973 oil crisis, 1979 energy crisis

- Energy development

- Petroleum politics

- World oil market chronology from 2003

- Oil-storage trade

- Oil and gas law in the United States

- Fossil fuels lobby

- Environmental issues

- Oil geology

- Oil-producing areas

- History of the petroleum industry in Canada

- History of the petroleum industry in the United States

- List of oil fields

- Oil megaprojects

- List of countries by oil production

- Oil industry in Azerbaijan

- Industry Research Projects

- Other articles

References

[edit]- ^ Sönnichsen, N. "Daily global crude oil demand 2006–2020". Statista. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Country Comparison :: Refined Petroleum Products – Consumption". Central Intelligence Agency – World Factbook. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Speight, James (2014). The Chemistry and Technology of Petroleum. Chemical Industries (5th ed.). CRC Press. doi:10.1201/b16559. ISBN 978-1439873892.

- ^ Halliday, Fred. The Middle East in International Relations: Cambridge University Press: US, p. 270 [ISBN missing]

- ^ "World Energy Investment 2023" (PDF). IEA.org. International Energy Agency. May 2023. p. 61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2023.

- ^ a b Bousso, Ron (8 February 2023). "Big Oil doubles profits in blockbuster 2022". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Details for 2020 from the more detailed diagram in King, Ben (12 February 2023). "Why are BP, Shell, and other oil giants making so much money right now?". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Crude oil including lease condensate production (Mb/d)". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ N.Y. Krylov, A.A. Bokserman, E.R.Stavrovsky. The Oil Industry of the Former Soviet Union. CRC Press, 1998. P. 187.

- ^ Altstadt, Audrey L. (1980). Economic Development and Political Reform in Baku: The Response of the Azerbaidzhani Bourgeoisie. Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies.

- ^ Daintith, Terence (2010). Finders Keepers?: How the Law of Capture Shaped the World Oil Industry. Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-936331-76-5.

- ^ a b Shirin Akiner, Anne Aldis. The Caspian: Politics, Energy and Security. Routledge, 2004. p. 5.

- ^ United States Congress, Joint Economic Committee. The Former Soviet Union in Transition. M.E. Sharpe, 1993. p. 463.

- ^ Quoted from: Tatyana Saiko. Environmental Crises. Pearson Education, 2000. p. 223.

- ^ Frank, Alison Fleig (2005). Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia (Harvard Historical Studies). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01887-7.

- ^ a b "Black Gold: Canada's Oil Heritage". The Corporation of the County of Lambton. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

The North American oil industry began in Oil Springs in 1858 in less spectacular fashion. James Miller Williams, a coachmaker from Hamilton, dug into the tar-like gum beds of Enniskillen Township to find their source. At a depth of fourteen feet, he struck oil. Williams immediately built a small refinery and began to produce illuminating oil for lamps – kerosene. It was Williams who was able to take full advantage of the ancient resource. Not only was he astute enough to look below the surface of the gum beds to find oil and to realize its commercial potential, but the timing of his discovery was perfect.

- ^ Turnbull Elford, Jean. Canada West's Last Frontier. Lambton County Historical Society, 1982, p. 110

- ^ Sarnia Observer and Lambton Advertiser, "Important Discovery in the Township of Enniskillen Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine," 5 August 1858, p. 2.

- ^ "Extraordinary Flowing Oil Well". Hamilton Times. 20 January 1862. p. 2. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

Our correspondent writes us from the Oil Springs, under date of the 16th inst., [an] interesting account of a flowing Oil well which has just been tapped. He says: I have just time to mention that to-day at half past eleven o'clock, a.m., Mr. John Shaw, from Kingston, C. W., tapped a vein of oil in his well, at a depth of one hundred and fifty-eight feet in the rock, which filled the surface well, (forty-five feet to the rock) and the conductors [sic] in the course of fifteen minutes, and immediately commenced flowing. It will hardly be credited, but nevertheless such is the case, that the present enormous flow of oil cannot be estimated at less than two thousand barrels per day, (twenty-four hours), of pure oil, and the quantity increasing every hour. I saw three men in the course of one hour, fill fifty barrels from the flow of oil, which is running away in every direction; the flat presenting the appearance of a sea of oil. The excitement is intense, and hundreds are rushing from every quarter to see this extraordinary well. Experience oil well diggers from the other side, affirm that this week equals their best flowing wells in Pennsylvania, and they pronounced the oil as being of a superior quality. This flowing well is situation on lot No. 10, Range B, Messrs. Sanborn & Co.'s Oil Territory.

- ^ John Steele Gordon Archived 2008-04-20 at the Wayback Machine "10 Moments That Made American Business," American Heritage, February/March 2007, "Drake, who seems to have awarded himself the title of colonel by which he is often known, had a great deal of trouble persuading a salt-drilling crew to try to drill for oil, but on August 27, 1859, he struck it at 69 feet."

- ^

Vassiliou, Marius S. (2 March 2009). "Titusville". Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry. Historical Dictionaries of Professions and Industries, No. 3. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press (published 2009). p. 508. ISBN 978-0810862883. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

In August 1859, an important early well was drilled by Edwin Drake outside Titusville, initiating the Pennsylvania oil boom.

- ^ a b Vassiliou, Marius (2018). Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry, 2nd Ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 621 pp.

- ^ Tolf, Robert W. (1976). "4: The World's First Oil Tankers". The Russian Rockefellers: The Saga of the Nobel Family and the Russian Oil Industry. Hoover Press. ISBN 0-8179-6581-5. p. 55.

- ^ Wells, Bruce (9 December 2021). "Horse-Drawn Oil Wagon seeks Museum". American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Ref accessed 02-12-89 by technical aspects and coast mapping. Kerr-McGee

- ^ "Project Redsand". www.project-redsand.com.

- ^ Wells, Bruce. "Offshore Petroleum History". American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Stanley, Rachel (24 July 2018). Comparison of Two Active Hydrocarbon Production Regions in Texas to Determine Boomtown Growth and Development: A Geospatial Analysis of Active Well Locations and Demographic Changes, 2000–2017 (PDF) (Thesis). Texas State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Industry Sectors", American Petroleum Institute, archived from the original on 25 January 2012, retrieved 12 May 2008

- ^ "Ranked in order of 2007 worldwide oil equivalent reserves as reported in "OGJ 200/100"". Oil & Gas Journal. 15 September 2008.

- ^ Pirog, Robert (21 August 2007). The Role of National Oil Companies in the International Oil Market (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 17 September 2009.Ranking by oil reserves and production, 2006 values

- ^ Helman, Christopher (16 July 2012). "The World's 25 Biggest Oil Companies". Forbes.

- ^ "Membership". International Association of oil and Gas Producers. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "The Transportation of Natural Gas". NaturalGas.org. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Refining and Product Specifications Module Overview". Petroleum Online. International Human Resources Development Corporation. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ Trench, Cheryl J. (December 2001). "How Pipelines Make the Oil Market Work – Their Networks, Operation and Regulation" (PDF). Allegro Energy Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013.

- ^ "The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures Key Data 2021" (PDF). European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Kocieniewski, David (3 July 2010). "As Oil Industry Fights a Tax, It Reaps Subsidies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Boudet, Hilary; Clarke, Christopher; Bugden, Dylan; Maibach, Edward; Roser-Renouf, Connie; Leiserowitz, Anthony (1 February 2014). "'Fracking' controversy and communication: Using national survey data to understand public perceptions of hydraulic fracturing". Energy Policy. 65: 57–67. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.10.017. ISSN 0301-4215.

- ^ Osborn, Stephen G.; Vengosh, Avner; Warner, Nathaniel R.; Jackson, Robert B. (17 May 2011). "Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (20): 8172–8176. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8172O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1100682108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3100993. PMID 21555547.

- ^ Diphare, Motshumi., Muzenda, Edison., Remediation of Contaminated Soils: A Review. Intl' Conf. on Chemical, Integrated Waste Management & Environmental Engineering (ICCIWEE'2014) April 15–16, 2014 Johannesburg.

- ^ M D Yuniati 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 118 012063

- ^ Liu, Rui., Jadeja, N. Rajendrasinh., Zhou, Qixing., Liu, Zhe. Treatment and Remediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils Using Selective Ornament Plants. Environmental Engineering Sci. 2012 Jun; 29(6): 494–501.

- ^ Lim, Wei Mei., Lau, Von Ee., Poh, Eong Phaik. A comprehensive guide of remediation technologies for oil contaminated soil — Present works and future directions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Volume 109, Issue 1, 15 August 2016, Pages 14-45.

- ^ "Air Quality Planning and Standards". Archived from the original on 19 February 2012.

- ^ Zamora, Robert; Yuan, Bin; Young, Cora J.; Wild, Robert J.; Warneke, Carsten; Washenfelder, Rebecca A.; Veres, Patrick R.; Tsai, Catalina; Trainer, Michael K.; Thompson, Chelsea R.; Sweeney, Colm; Stutz, Jochen; Soltis, Jeffrey; Senff, Christoph J.; Parrish, David D.; Murphy, Shane M.; Stuart A. McKeen; Li, Shao-Meng; Li, Rui; Lerner, Brian M.; Lefer, Barry L.; Langford, Andrew O.; Koss, Abigail; Helmig, Detlev; Graus, Martin; Gilman, Jessica B.; Flynn, James H.; Field, Robert A.; Dubé, William P.; deGouw, Joost A.; Banta, Robert M.; Ahmadov, Ravan; Roberts, James M.; Brown, Steven S.; Edwards, Peter M. (1 October 2014). "High winter ozone pollution from carbonyl photolysis in an oil and gas basin". Nature. 514 (7522): 351–354. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..351E. doi:10.1038/nature13767. PMID 25274311. S2CID 4466316.

- ^ a b Benjamin Franta, "On its 100th birthday in 1959, Edward Teller warned the oil industry about global warming", The Guardian, 1 January 2018 (page visited on 2 January 2018).

- ^ Martín, Mariano, ed. (2016). Alternative Energy Sources and Technologies. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28752-2. ISBN 978-3-319-28750-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Mau, Mark; Edmundson, Henry (2015). Groundbreakers: the Story of Oilfield Technology and the People Who Made It Happen. UK: FastPrint. ISBN 978-178456-187-1.

- Nevins, Alan. John D. Rockefeller The Heroic Age Of American Enterprise (1940); 710pp; favorable scholarly biography; online

- Ordons Oil & Gas Information & News

- Robert Sobel The Money Manias: The Eras of Great Speculation in America, 1770–1970 (1973) reprinted (2000).

- Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, (Simon and Schuster 1991; paperback, 1993), ISBN 0-671-79932-0.

- Matthew R. Simmons, Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy, John Wiley & Sons, 2005, ISBN 0-471-73876-X.

- Matthew Yeomans, Oil: Anatomy of an Industry (New Press, 2004), ISBN 1-56584-885-3.

- Smith, GO (1920): Where the World Gets Its Oil: National Geographic, February 1920, pp 181–202

- Marius Vassiliou, Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry, 2nd Ed.. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018, 621 pp. ISBN 978-1-5381-1159-8.

- Ronald W. Ferrier; J. H. Bamberg (1982). The History of the British Petroleum Company: Volume 1, The Developing Years, 1901–1932. Cambridge UP. pp. A–13. ISBN 978-0521246477.

- Miryusif Mirbabayev, Concise History of Azerbaijani Oil. Baku, Azerneshr, (2008), 340pp.

- Miryusif Mirbabayev, "Brief history of the first drilled oil well; and the people involved". Oil-Industry History (USA), 2017, v. 18, #1, pp. 25–34.

- James Douet, The Heritage of the Oil Industry TICCIH Thematic Study , The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage, 2020, 79pp.

External links

[edit]Petroleum industry

View on GrokipediaHistory

Pre-Modern and Ancient Uses

Petroleum originates from the remains of ancient marine organisms, plankton, and terrestrial plants that accumulated in low-oxygen sedimentary basins. This organic matter undergoes diagenesis to form kerogen, followed by catagenesis under millions of years of increasing heat, pressure, and anaerobic conditions, maturing into crude oil and natural gas.[14][15][16] Petroleum, primarily in the form of bitumen derived from natural seeps, was utilized by ancient Mesopotamian civilizations such as the Sumerians for construction, waterproofing, and adhesive purposes starting around 3000 BCE. Bitumen served as mortar to bind bricks in buildings, palaces, and ziggurats, including the Darius Palace in Susa, and was applied to caulk ships and seal water reservoirs against leakage.[17][18] Trade networks for bitumen extended across the ancient Near East, with Mesopotamian deposits dominating supply due to abundant seeps in regions like modern-day Iraq.[19] In ancient Egypt, bitumen imported from the Middle East was employed for embalming and mummification processes, valued for its preservative qualities in treating bodies as early as the Third Dynasty around 2600 BCE. Egyptians also used it medicinally as a disinfectant and insecticide, applying it to wounds and in rituals.[17] Its role in waterproofing extended to coating structures, contributing to the durability of elements in pyramids and other monuments.[20] Persian and Elamite societies similarly exploited bitumen for architectural mortar in temples and fortifications, while naphtha fractions were weaponized in incendiary mixtures akin to Greek fire by the Achaemenid Empire around 500 BCE. In prehistoric contexts, even Neanderthal populations hafted flint tools with bitumen as early as 50,000 years ago, demonstrating its adhesive utility predating organized civilizations.[17] Pre-modern applications persisted into the early modern era, with indigenous groups in the Americas collecting bitumen from seeps for hafting arrowheads, sealing watercraft, and medicinal salves; California Indians, for instance, used it for gluing, waterproofing skirts, and setting bones as documented in archaeological remains from 5000 BCE onward. In Eurasia, shallow wells tapped seeps for oil used in lamps and lubricants, though extraction remained rudimentary until the 18th century.[21][22] These uses relied on surface or near-surface seeps, limiting scale and prefiguring no systematic industry.[23]19th Century Commercialization

Commercialization of petroleum in the 19th century was driven by the demand for kerosene as a superior illuminant to whale oil and camphene, enabling scalable refining and drilling technologies. In 1853, Polish pharmacist Ignacy Łukasiewicz developed a method to distill kerosene from crude oil seeps in Austrian Galicia, producing a cleaner-burning fuel for lamps.[24] He constructed the world's first kerosene lamp that year and lit the first street lamp using it in Gorlice in 1854, while establishing an early refinery in Ulaszowice in 1856 and the Bóbrka oil mine near Gorlice, marking initial industrial extraction in Europe.[25] The United States saw the launch of modern petroleum production with Edwin Drake's well in Titusville, Pennsylvania, completed on August 27, 1859, after drilling to 69.5 feet using a steam-powered rig and drive pipe to stabilize the borehole.[26] This well initially yielded 25 barrels per day, prompting a rapid oil rush in the Oil Creek Valley as investors leased land and drilled additional wells.[27] Pennsylvania output surged from approximately 2,000 barrels in 1859 to several hundred thousand barrels in 1860 and 3 million barrels by 1862, with global production reaching 500,000 barrels in 1860, primarily from U.S. sources.[28] [27] Refining capacity expanded to process the kerosene fraction, as crude oil's primary value lay in illumination rather than fuel uses initially. By 1860, dozens of small refineries operated in Pennsylvania and nearby states, shipping kerosene via barrel to markets in New York and beyond.[29] Consolidation began as efficiencies favored larger operations; John D. Rockefeller incorporated Standard Oil Company in Ohio on January 10, 1870, with $1 million capital, leveraging railroad rebates and vertical integration to control refining.[30] By the late 1870s, Standard Oil refined about 90% of U.S. kerosene, standardizing production and distribution amid volatile prices from overproduction booms and busts.[27] Technological adaptations, such as cable-tool drilling and wooden derricks, supported shallow well development up to 100-200 feet in Pennsylvania's sandstone reservoirs, yielding high initial flows but rapid declines that spurred geographic expansion to Ohio and West Virginia by the 1860s.[29] These innovations, absent earlier reliance on surface seeps, established petroleum as a commodity industry, with export markets emerging for kerosene to Europe and Asia by the 1870s.[27]20th Century Expansion and Cartel Formation

The petroleum industry's expansion in the early 20th century was propelled by major discoveries and surging demand from internal combustion engines. The Spindletop geyser in Beaumont, Texas, erupted on January 10, 1901, yielding over 100,000 barrels per day initially and catalyzing the Texas oil boom, which elevated U.S. production from 63 million barrels in 1900 to 442 million by 1910.[31] This shift marked petroleum's transition from primarily kerosene for lighting to gasoline as the dominant product, driven by mass automobile production starting in the 1890s and accelerating with Henry Ford's Model T in 1908.[3] Internationally, the 1908 discovery in Masjed Soleiman, Persia (modern Iran), by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company established a foothold in the Middle East, producing 235,000 barrels annually by 1912 and fueling British naval conversions to oil.[31] Further discoveries amplified global output through mid-century. The East Texas Oil Field, found in 1930, became the largest in the contiguous U.S., with cumulative production exceeding 5 billion barrels and prompting regulatory interventions to curb overproduction.[32] In 1938, oil was confirmed in Saudi Arabia's Dammam No. 7 well, leading to the formation of the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) and reserves estimated at over 100 billion barrels by the 1940s, shifting production centers eastward as U.S. fields matured.[31] World War II accelerated demand for aviation fuel and military logistics, with global consumption rising from 1 billion barrels in 1939 to peaks supporting Allied efforts, while post-war economic recovery and suburbanization in the West boosted annual growth to 7-8% through the 1950s.[33] Cartel-like arrangements emerged among major oil companies to manage supply and stabilize prices amid volatile discoveries. The "Seven Sisters"—comprising Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon), Standard Oil of New York (Mobil), Standard Oil of California (Chevron), Texaco, Gulf Oil, Anglo-Persian Oil (BP), and Royal Dutch Shell—controlled approximately 85% of global oil reserves and production by the 1940s through concessions, joint ventures, and pricing coordination.[34] A pivotal agreement was the 1928 Red Line Agreement, signed by these firms (plus Compagnie Française des Pétroles), delineating Iraq's oil territories and restricting independent ventures to preserve oligopolistic control.[34] These entities operated as a de facto cartel, setting posted prices and allocating markets to avoid destructive competition, as evidenced by their dominance in Middle Eastern concessions where host governments initially held limited bargaining power. Producing countries responded with their own cartel in 1960. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was founded on September 14, 1960, in Baghdad by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela, following unilateral price cuts by the Seven Sisters in 1959 that reduced posted prices by 10-14%.[35][36] OPEC aimed to coordinate policies for stable markets and fair revenues, initially representing 80% of non-communist exports, though its influence grew post-1970 through production quotas.[35] This formation reflected host nations' push against company dominance, leveraging nationalized concessions to assert control over rents previously captured by the integrated majors.[37]Post-1970s Crises and Technological Shifts

The 1973 oil crisis erupted on October 17, 1973, when Arab members of OPEC imposed an embargo on oil exports to countries supporting Israel during the Yom Kippur War, coupled with production cuts that quadrupled global crude oil prices from about $3 per barrel to $12 per barrel by January 1974.[38][39][40] This shock disrupted supply chains, triggered rationing in importing nations, and fueled stagflation, with U.S. inflation surging to 11% in 1974 and real GDP declining by 0.5%.[41] The 1979 energy crisis followed the Iranian Revolution, which halted Iranian oil exports and reduced global output by 4.8 million barrels per day—7% of world supply—prompting panic buying and driving prices from $13 per barrel in mid-1979 to $34 per barrel by mid-1980, exacerbated by the Iran-Iraq War starting in 1980.[42][43] These events amplified economic volatility, with U.S. gasoline lines reappearing and inflation exceeding 13%, underscoring vulnerabilities in reliance on OPEC-controlled supplies from the Middle East.[44] In response, governments and firms pursued energy independence through conservation—such as the U.S. Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards enacted in 1975, which improved vehicle efficiency—and alternative sources, but sustained high prices incentivized technological innovation in exploration and extraction.[41] Advances in 3D seismic imaging during the 1970s and 1980s enhanced subsurface mapping accuracy, reducing dry well risks, while directional and horizontal drilling techniques, pioneered in the U.S. in the 1980s, allowed access to extended reservoirs.[45] The convergence of horizontal drilling with multi-stage hydraulic fracturing—refined from early 1940s concepts but commercialized for shale in the late 1990s by Mitchell Energy in the Barnett Shale—sparked the U.S. shale revolution around 2005.[46][47] This unlocked vast tight oil resources, boosting U.S. crude production from 5.0 million barrels per day in 2008 to 9.3 million by 2017, overtaking Saudi Arabia as the world's top producer by 2018 and flooding global markets to suppress prices below $50 per barrel in 2015-2016.[48][49] Parallel deepwater advancements, including dynamic positioning systems, subsea production tiebacks, and managed pressure drilling developed in the 1990s, enabled exploitation of ultra-deep reservoirs over 7,000 feet water depth, with fields like Brazil's pre-salt layers and U.S. Gulf of Mexico projects such as Chevron's Anchor (first oil in 2024) adding billions of barrels to recoverable reserves.[50][51] These innovations, driven by private R&D amid post-crisis incentives, expanded global supply by over 10 million barrels per day since 2000, countering depletion fears and diluting OPEC's pricing power through elastic non-OPEC responses.[52]Operational Structure

Upstream: Exploration and Production

The upstream sector of the petroleum industry involves the search for and extraction of crude oil and natural gas reserves. This phase includes exploration activities such as geological and geophysical surveys to identify potential hydrocarbon deposits, followed by drilling exploratory wells to confirm the presence of commercially viable quantities. Production then entails developing fields through production wells to bring hydrocarbons to the surface.[53][54] Exploration begins with acquiring leases or rights to explore acreage onshore or offshore, often guided by surface geology, gravity, magnetic, and seismic surveys. Seismic technology, particularly 3D and 4D imaging, has revolutionized subsurface mapping by providing detailed acoustic images of rock layers to pinpoint traps where oil and gas accumulate. Wildcat wells, drilled in unproven areas, carry high risk, with success rates historically around 1 in 10, though advanced data analytics and machine learning improve targeting accuracy. Once a discovery is made, appraisal wells delineate the reservoir's extent and characteristics to assess economic feasibility.[54][55][56] Production phases typically start with primary recovery, relying on natural reservoir pressure to drive oil to the wellbore, yielding 5-15% of original oil in place. Secondary recovery methods, such as water or gas injection, maintain pressure and sweep hydrocarbons toward producers, recovering an additional 20-40%. Enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques, including thermal, chemical, or CO2 injection, target remaining reserves in mature fields. Unconventional resources like shale oil require hydraulic fracturing combined with horizontal drilling to access tight formations, enabling production from low-permeability rocks.[57][58][59] In 2024, global crude oil production reached approximately 101.8 million barrels per day, led by the United States at 13.2 million barrels per day, primarily from shale plays in the Permian Basin, followed by Saudi Arabia and Russia. These figures reflect technological advancements that have shifted production dynamics toward non-OPEC nations, with U.S. output setting records through efficient drilling and completion operations. Offshore production, accounting for about 30% of global supply, involves complex subsea systems and floating platforms in deepwater environments.[60][61][62]Midstream: Transportation, Storage, and Logistics

The midstream sector of the petroleum industry encompasses the transportation of crude oil and natural gas from upstream production facilities to downstream refineries and markets, primarily via pipelines, tankers, rail, and trucks, as well as interim storage in tanks and terminals to manage supply fluctuations. Pipelines constitute the predominant mode, handling over 65% of global crude oil transportation volume due to their efficiency and lower per-barrel costs compared to alternatives. In 2023, the crude oil pipeline transport market was valued at approximately $69.91 billion, reflecting steady growth driven by expanded networks in producing regions.[63][64] Global oil pipeline infrastructure spans about 504,000 kilometers, facilitating bulk movement across continents, with major networks concentrated in North America, Russia, and the Middle East. These systems operate under high pressure to propel viscous crude over long distances, minimizing evaporation losses and contamination risks inherent in alternative methods. Maritime transport via oil tankers complements pipelines for seaborne trade, accounting for the majority of intercontinental shipments; the global tanker fleet comprises roughly 7,500 vessels with a combined deadweight tonnage exceeding 679 million tons as of 2024, enabling the carriage of over 2 billion tons of crude annually. Very large crude carriers (VLCCs), typically 200,000–500,000 DWT, dominate long-haul routes from producers like Saudi Arabia to consumers in Asia and Europe. Rail and truck transport serve niche roles, particularly for short-haul or remote shale plays, but represent less than 5% of total volume due to higher costs and logistical constraints.[65][66][67] Storage infrastructure buffers production variability and geopolitical disruptions, with commercial terminals worldwide numbering around 7,935 and offering approximately 1.6 million cubic meters of capacity for crude and products. Floating-roof tanks predominate to reduce vapor emissions, while underground caverns provide secure, large-scale options in salt domes. Strategic petroleum reserves (SPRs) augment commercial capacity for national security; the United States maintains the largest at 714 million barrels in four Gulf Coast sites, designed for rapid release during supply crises. Other major holders include China (over 500 million barrels estimated) and Japan, collectively ensuring IEA members cover at least 90 days of net imports. Logistics coordination integrates these elements through real-time monitoring via SCADA systems, optimizing throughput amid bottlenecks like pipeline bottlenecks in export hubs or tanker queuing at chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz. Aging infrastructure and regulatory hurdles, including permitting delays for expansions, pose ongoing challenges, as evidenced by Permian Basin constraints limiting U.S. output growth in 2024.[68][69][70][71]Downstream: Refining, Processing, and Distribution

The downstream sector transforms crude oil into marketable products through refining and processing, followed by distribution to consumers and industries. Refineries separate crude oil via fractional distillation into fractions such as naphtha, kerosene, diesel, and heavy residues based on boiling points, yielding initial products comprising about 40-50% gasoline precursors from typical crudes.[8] Conversion processes like catalytic cracking then break heavier hydrocarbons into lighter, higher-value fuels; this method applies heat, pressure, and catalysts to achieve yields up to 50% gasoline from heavy feeds, significantly increasing efficiency over simple distillation.[8][72] Additional treatments, including hydrocracking and reforming, further upgrade products by adding hydrogen or rearranging molecules to meet specifications for octane rating and sulfur content.[8] Global refining capacity stood at 103.80 million barrels per day in 2024, with China and the United States leading additions amid expansions in Asia.[73] The Jamnagar Refinery in India operates as the largest single complex at 1.24 million barrels per day, processing heavy crudes into fuels and petrochemical feedstocks.[74] Processing extends to petrochemical production, where refinery outputs like naphtha serve as inputs for plastics and chemicals, accounting for roughly 10-15% of refined output in integrated facilities.[75] Distribution channels move refined products from refineries to markets via pipelines for bulk transport, tanker ships for international trade, and trucks for final delivery to retail sites.[76] In the United States, pipelines handle over 70% of refined product movement to terminals, where blending occurs before trucking to gasoline stations.[77] Marketing encompasses wholesale supply to industries and retail sales, with major integrated firms like ExxonMobil and Shell managing networks of thousands of outlets worldwide.[76] This segment generated refining margins averaging $8.37 per barrel in May 2025, reflecting volatility tied to crude prices and demand.[78]Economic Significance

Global Supply Chains and Market Dynamics

The petroleum industry's global supply chains encompass extraction primarily in the Middle East, North America, and Russia, followed by transportation via pipelines and supertankers, and refining concentrated in importing regions like Asia and Europe. In 2024, worldwide crude oil production reached approximately 101.8 million barrels per day (bpd), with the United States leading at 21.7 million bpd, accounting for 22% of the total, driven largely by shale developments in the Permian Basin.[62][60] Saudi Arabia and Russia followed with 11.13 million bpd and 10.75 million bpd, respectively, while non-OPEC+ producers like the US and Canada contributed to supply growth amid OPEC+ cuts.[62] International trade volumes in 2024 saw China as the largest importer at 11.1 million bpd, sourcing heavily from Russia, which displaced traditional Middle Eastern suppliers due to discounted prices post-Ukraine invasion sanctions.[79] Key export hubs include Saudi Arabia's Ras Tanura terminal and US Gulf Coast ports, with seaborne crude shipments totaling around 2 billion metric tons annually, vulnerable to chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz, through which 20% of global oil flows.[80] Midstream logistics rely on very large crude carriers (VLCCs) for long-haul routes from the Persian Gulf to Asia, while pipelines like Russia's Druzhba and the US Keystone connect regional producers to refineries.[81] Market dynamics are shaped by benchmark prices, with Brent crude averaging $80.52 per barrel in 2024, reflecting a balance between OPEC+ production restraint and surging non-OPEC output.[82] OPEC's share of global crude production stood at 26.1% in 2024, down from higher levels due to US shale's elasticity, which added flexibility and lowered break-even costs, pressuring cartel pricing power.[83] OPEC+ implemented voluntary cuts totaling 3.66 million bpd extended into 2025 to counter weak demand and high inventories, yet non-OPEC growth, forecasted at 1.5 million bpd, sustained downward price pressure amid slowing Chinese economic expansion.[84] Futures markets on exchanges like NYMEX and ICE facilitate hedging, with WTI-Brent spreads averaging under $5 per barrel, underscoring interconnected global pricing.[85] The oil and gas industry generally lacks a strong economic moat because it is fundamentally a commodity business where prices are determined by global supply and demand dynamics, rather than by individual companies. This results in limited enduring pricing power or structural barriers to protect returns for most participants.[86][87] Shale production's rise since 2010 transformed dynamics by making the US a net exporter, reducing global import dependence on OPEC and enabling rapid response to price signals, unlike slower conventional field developments.[88] This shift eroded OPEC's market share from over 40% a decade prior to under 25% by 2024, prompting strategic output hikes to regain influence despite short-term revenue losses for members like Saudi Arabia.[89] Geopolitical events, including sanctions on Russia and Iran, amplified volatility, with 2022-2024 supply disruptions pushing prices above $100 per barrel temporarily before easing on ample spare capacity.[90] Demand-side factors, particularly Asia's 60% share of global consumption growth, drive chain reconfiguration toward lighter crudes suitable for petrochemicals.[84]Contributions to Employment and National Economies

The petroleum industry directly employs approximately 12.4 million workers worldwide in upstream supply activities as of 2023, encompassing exploration, drilling, and production roles, with additional indirect and induced jobs amplifying the total economic footprint through supply chains and local spending.[91] These figures reflect growth driven by new project developments amid sustained global demand, though employment varies by region, with concentrations in oil-producing nations where the sector often serves as a primary economic driver.[92] In the United States, the oil and natural gas industry supports 9.8 million jobs, equivalent to 5.6 percent of total national employment, including 384,000 direct upstream positions in 2024; this includes high-wage roles in extraction, with average annual earnings exceeding those in manufacturing by about 50 percent due to technical demands.[93] [94] The sector's multiplier effect generates further employment in ancillary industries like equipment manufacturing and logistics, contributing to regional booms in states such as Texas and North Dakota, where petroleum activities have historically offset declines in other extractive sectors.[93] For national economies, petroleum dominates fiscal revenues in major producers; in Saudi Arabia, oil extraction accounts for 46 percent of GDP, funding public expenditures and sovereign wealth accumulation despite diversification efforts under Vision 2030 that elevated non-oil activities to 50 percent of real GDP by 2023.[95] [96] In resource-dependent economies like those of OPEC members, petroleum exports comprise over 70 percent of total exports in aggregate, enabling infrastructure investments and social programs while exposing budgets to price volatility, as evidenced by Saudi Arabia's 4.3 percent GDP contraction in 2023 amid production cuts. [97] This reliance underscores causal linkages between reserves, production capacity, and state capacity, with revenues directly financing up to 60 percent of government budgets in peak years.[98]Innovation Spillovers and Value-Added Industries

The petroleum industry's value-added segments, especially petrochemicals, transform low-value crude oil and natural gas liquids into high-value derivatives such as ethylene, propylene, and aromatics, which form the basis for plastics, rubbers, adhesives, and pharmaceuticals. Globally, the petrochemical market reached $584.5 billion in value in 2022, accounting for about 12% of oil demand and projected to grow amid rising consumption in packaging, electronics, and automotive applications.[99] In the United States, petrochemical operations contribute over $220 billion annually to GDP and sustain more than 373,000 direct and indirect jobs, with capital investments exceeding $12.5 billion in recent years.[100] These sectors amplify economic returns, as processed outputs command premiums far exceeding raw hydrocarbon prices—e.g., a barrel of naphtha feedstock yields polymers worth multiples of its input cost—while fostering ancillary industries like synthetic textiles and fertilizers.[100] Innovation spillovers from petroleum R&D extend beyond energy, transferring technologies and expertise to non-oil sectors via personnel mobility, licensing, and collaborative initiatives. During the Cold War (1940s–1980s), major oil firms including Exxon, Mobil, Texaco, and Schlumberger funded seismic data processing advancements, spilling over to U.S. computing and semiconductors through investments (e.g., Exxon's stake in Zilog) and key personnel like physicist John Bardeen from Gulf Oil and engineer Gordon Teal to Texas Instruments, which developed tools like the TIAC system in 1962 for digital signal processing later adopted broadly.[101] In earth sciences, airborne magnetic surveys pioneered for hydrocarbon prospecting identified the Chicxulub impact crater in 1978, informing paleontology on dinosaur extinction, while cable-free seismometers enhanced earthquake monitoring, as deployed with over 900 nodes at Mount St. Helens in 2014.[102] Medical applications include reservoir simulation models adapted for MRI interpretation via Norwegian firm IRIS's $1.1 million project, and fiber-optic sensors from well monitoring repurposed by Opsens for precise arterial pressure gauging in cardiac care.[102] Subsea remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), refined for offshore drilling, supported oceanographic research through the SERPENT project since 2002, revealing deep-sea ecosystems inaccessible otherwise.[102] In space exploration, oilfield percussion drills enabled the Mars rover Curiosity's 2.5-inch boreholes in 2013, and diving suit leak-detection systems influenced NASA spacesuits via Oceaneering.[102] Renewable energy benefits from high-temperature drilling bits, as Baker Hughes supplied for Iceland's geothermal fields exceeding 570°F, and CO2 capture techniques from enhanced oil recovery applied to emissions mitigation.[102] Such transfers, often undocumented in aggregate, underscore the sector's externalities in bolstering technological progress across domains.[101]Geopolitical Dimensions

Resource Nationalism and OPEC Influence

Resource nationalism in the petroleum industry involves governments enhancing state control over oil and gas resources through measures such as nationalization, increased taxation, royalty hikes, and mandates for local content or technology transfer from international oil companies (IOCs). This phenomenon has occurred in cycles, driven by high commodity prices that embolden producers to renegotiate terms or expropriate assets, often at the expense of foreign investment efficiency. A prominent wave emerged in the 1970s amid rising oil prices, with countries like Algeria, Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, and Venezuela nationalizing foreign-held concessions, shifting from concessionary systems to production-sharing agreements that retained greater resource rents for the state.[103][104] The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), founded on September 14, 1960, in Baghdad by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela, amplified resource nationalist tendencies by enabling collective bargaining against IOCs, which previously dominated pricing and production via long-term concessions. OPEC's strategy of coordinating output quotas among members—controlling approximately 40% of global oil supply—allows it to influence prices by restricting supply during low-price periods or expanding it amid gluts, as seen in the 1973 Arab oil embargo that quadrupled crude prices from about $3 to $12 per barrel in response to Western support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War. This mechanism has empowered member governments to capture higher fiscal revenues, funding state expansion, but it has also introduced market volatility, with quotas often undermined by cheating or non-OPEC competition like U.S. shale.[105][106][107] OPEC's evolution into OPEC+ in late 2016, incorporating non-OPEC producers like Russia and accounting for over 50% of global output, extended this influence to stabilize prices post-shale boom and amid demand shocks. By 2025, OPEC+ continued quota adjustments, such as a modest 137,000 barrels per day increase for November, to balance supply amid geopolitical tensions and slowing demand growth. Resource nationalism intersects with OPEC dynamics as members leverage the cartel's pricing power to justify aggressive policies; however, empirical evidence shows such measures frequently deter investment, leading to production declines in nationalized firms like Venezuela's PDVSA, where output fell from over 3 million barrels per day in the early 2000s to under 1 million by 2020 due to expropriations and mismanagement. In contrast, moderated nationalism in Latin America post-2014 oil bust has correlated with renewed foreign investment to offset fiscal strains in state operators.[108][109][103]Wars, Sanctions, and Supply Disruptions

The 1973 OPEC oil embargo, initiated by Arab members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) in response to Western support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War, targeted the United States and other nations, halting oil exports and imposing production cuts that reduced global supply by approximately 5 million barrels per day.[41] This action quadrupled crude oil prices from about $3 per barrel to nearly $12 per barrel by early 1974, triggering widespread energy shortages, inflation, and economic recessions in importing countries.[110] The embargo highlighted petroleum's role as a geopolitical weapon, with OAPEC leveraging control over 60% of global exports to enforce political objectives, though long-term effects included accelerated non-OPEC production and energy conservation measures.[111] The Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988) severely disrupted oil production in both belligerents, which together accounted for over 10% of global supply prior to the conflict. Iraq's exports halted almost entirely in the early phases due to attacks on its Gulf loading facilities, while Iranian strikes and an initial oil workers' strike reduced Iran's output to near zero, contributing to a 5–7% global supply shortfall and exacerbating the 1979 energy crisis with prices surging to $40 per barrel.[112] Over the war's duration, repeated targeting of oil infrastructure—such as Iraq's strikes on Iran's Kharg Island terminal and Iran's assaults on Iraqi tankers—led to fluctuating but persistently lower exports, with Iran's production averaging below 2 million barrels per day against a pre-war capacity of over 5 million.[113] These disruptions strained global markets but were mitigated by increased Saudi output and drawdowns from strategic reserves, underscoring the vulnerability of concentrated production in the Persian Gulf.[114] Iraq's invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990, seized control of Kuwait's 2.5 million barrels per day production alongside Iraq's own 3.5 million, removing about 4.5–5 million barrels per day from the market and driving Brent crude prices above $40 per barrel.[115] The conflict prompted UN sanctions and a U.S.-led coalition response, culminating in Operation Desert Storm in January 1991, after which retreating Iraqi forces ignited over 600 Kuwaiti oil wells, releasing millions of barrels of crude and smoke that disrupted regional weather and required months to extinguish.[116] Post-liberation recovery was slow, with Kuwaiti output remaining halved for years, though global prices moderated due to spare capacity from OPEC members like Saudi Arabia; the episode reinforced perceptions of oil as a motivator for conflict, with Iraq citing Kuwait's overproduction and alleged theft from shared fields as pretexts.[117] Subsequent U.S.-led sanctions and the 2003 Iraq invasion further interrupted Iraqi production, which fell to under 2 million barrels per day amid insurgency attacks on pipelines and facilities, representing a temporary 3–4% global supply hit before rebounding with foreign investment.[118] In parallel, targeted sanctions have constrained exports from other producers: U.S. measures reimposed on Iran in 2018 after withdrawal from the JCPOA reduced its exports from 2.5 million barrels per day to about 0.5 million by 2020, though evasion tactics like ship-to-ship transfers sustained sales primarily to China, limiting broader supply shocks to roughly 1–1.5% of global volumes.[119] Similarly, U.S. sanctions on Venezuela since 2017–2019 halved its output from over 2 million to under 1 million barrels per day by 2020, exacerbating domestic decline from mismanagement and forcing discounted sales to buyers like China and India.[120] The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine prompted Western sanctions, including an EU seaborne oil import ban and G7 price cap implemented in December 2022, which curtailed Russia's seaborne crude exports by about 1 million barrels per day initially while redirecting volumes to Asia via shadow fleets.[121] Russian oil revenues declined post-price cap despite stable production around 10 million barrels per day, as discounts eroded margins, contributing to volatile global prices peaking near $130 per barrel in March 2022 before stabilizing; these measures avoided severe shortages through non-sanctioned buyers absorbing redirected supply but heightened shipping risks and insurance costs.[122] Ongoing enforcement, including recent 2025 U.S. actions against entities like Rosneft, continues to pressure Russia's energy sector, potentially tightening supply if evasion networks falter.[123] Across these episodes, disruptions have repeatedly demonstrated that while short-term price spikes ensue, market resilience via spare capacity and substitution often tempers long-term impacts, though risks persist from chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz.[124]Energy Security and Strategic Independence

The pursuit of energy security in the petroleum industry centers on ensuring reliable access to crude oil and refined products amid risks of supply interruptions, price volatility, and geopolitical coercion. Nations achieve strategic independence by bolstering domestic extraction capabilities, diversifying import sources, and maintaining emergency stockpiles to mitigate vulnerabilities inherent in global trade dependencies. Historical precedents, such as the 1973 OPEC embargo that withheld Arab oil exports to the United States and allies, demonstrated how coordinated production cuts could weaponize petroleum, spiking prices from $3 to $12 per barrel and triggering recessions.[125] This event catalyzed the establishment of the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) in 1975, with a capacity of 714 million barrels stored in Gulf Coast salt caverns to buffer against future shocks.[126] Domestic production expansions have proven pivotal for independence, as exemplified by the U.S. shale revolution initiated in the mid-2000s through hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. U.S. crude oil output rose from 5.0 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2008 to 13.3 million bpd by 2023, surpassing Saudi Arabia to become the world's largest producer and enabling net petroleum exports starting in September 2019.[127] This shift reduced U.S. import reliance from over 60% of consumption in the early 2000s to near self-sufficiency, enhancing resilience against foreign manipulations and contributing to a record net energy surplus of 8.5 quadrillion Btu in 2023.[128] Similarly, Norway's North Sea developments since the 1970s have secured over 90% domestic supply coverage, insulating it from broader market turbulence.[129] OPEC and its allies (OPEC+) exert substantial influence over global supply security by controlling approximately 40% of production capacity and over 80% of proven reserves, enabling quota adjustments that stabilize or constrict output to defend prices.[105] [130] Such interventions, including voluntary cuts of 2.2 million bpd announced in 2023, can exacerbate shortages during demand spikes or sanctions, as seen in responses to U.S. shale gains.[131] Geopolitical disruptions further highlight risks: Western sanctions on Russian oil post-2022 Ukraine invasion reduced Moscow's exports to Europe by over 90% from pre-war levels, forcing rerouting to Asia and contributing to Brent crude averaging $100 per barrel in early 2022.[132] Europe's heavy import dependence—62.5% of total energy in 2022, with oil comprising about 60% of fossil fuel imports—amplified vulnerabilities during the crisis, driving wholesale prices to record highs and prompting emergency measures like the EU's REPowerEU plan to cut Russian reliance by 2027.[133] [134] Countries lacking robust reserves or production, such as Germany (importing 95% of its oil), faced acute exposure, underscoring how strategic independence requires not only reserves like the SPR—deployed 180 million barrels in 2022 to temper inflation—but also sustained investment in upstream capabilities to counter cartel dominance and adversarial suppliers.[125] [135]Technological Advancements

Exploration and Reservoir Characterization

Exploration begins with geological and geophysical assessments to identify prospective basins and traps capable of holding hydrocarbons. Surface indicators, such as natural oil seeps or structural features like anticlines, guide initial site selection, but subsurface imaging via seismic reflection surveys dominates modern practice. These surveys generate acoustic waves—using vibrators on land or air guns offshore—that propagate downward, reflect off rock interfaces, and are recorded by geophones or hydrophones to construct images of stratigraphic layers and potential reservoirs up to several kilometers deep.[136][137] Two-dimensional (2D) seismic lines provided early linear profiles, but three-dimensional (3D) surveys, widespread since the 1990s, offer volumetric data for precise fault and horizon mapping, reducing dry hole risks. Four-dimensional (4D) time-lapse seismic monitors reservoir changes over production phases. Complementary methods include gravity and magnetic surveys for basin-scale anomalies, though seismic remains paramount for structural detail. Advances in the 2020s integrate artificial intelligence for automated fault detection and full waveform inversion, improving resolution in complex geology like subsalt or shale plays.[138][56] Exploratory drilling tests these prospects; wildcat wells, drilled without prior production nearby, yield commercial success rates of approximately 27% from 2020 to 2024, up from 21% in 2010-2014, reflecting refined targeting amid fewer wells drilled overall.[139] Reservoir characterization quantifies discovered accumulations' properties—porosity, permeability, saturation, pressure, and fluid types—to estimate recoverable volumes and inform development. Porosity, the void fraction in rock matrix, typically spans 5% to 25% in conventional sandstone or carbonate reservoirs, directly governing storage capacity; higher values correlate with coarser grains but diminish with compaction or cementation.[140] Permeability, quantifying interconnectivity of pores for fluid flow, ranges from 100 to 500 millidarcies in viable zones, with fractures enabling higher effective rates in tight formations.[141] Techniques encompass wireline logging (e.g., gamma ray, resistivity, sonic tools) during appraisal wells to derive petrophysical logs, core extraction for lab-measured properties, and pressure transient analysis for dynamic behavior.[142] Integration via geostatistical modeling and seismic inversion constructs heterogeneous 3D models, incorporating uncertainty from sparse data points. Relative permeability curves assess multiphase flow (oil, gas, water), while saturation profiles via nuclear magnetic resonance logging distinguish movable hydrocarbons. Machine learning enhances prediction of facies distribution and upscaling from core to seismic scales, optimizing recovery forecasts in heterogeneous reservoirs.[143][56] Accurate characterization underpins economic viability, as overestimation risks stranded assets, with empirical validation through pilot production essential given inherent geological variability.[144]Extraction and Recovery Techniques

Petroleum extraction begins with primary recovery, where natural reservoir energy drives oil to the surface through production wells, typically recovering 5 to 15 percent of the original oil in place (OOIP).[145][146] This phase relies on mechanisms such as solution gas drive, where dissolved gas expands and pushes oil upward; gas cap drive, involving expansion of a free gas layer; and aquifer water drive, where encroaching water displaces oil.[147] Recovery factors vary by reservoir characteristics, with solution gas drives often yielding lower rates around 5 to 10 percent due to rapid pressure depletion.[148] Secondary recovery techniques, applied after primary depletion, maintain reservoir pressure and sweep oil toward wells, boosting total recovery to 20 to 40 percent of OOIP.[149] Common methods include waterflooding, which injects water to displace oil and restore pressure, and immiscible gas injection, using nitrogen or produced gas to achieve similar effects.[150] These approaches improve volumetric sweep efficiency but leave significant oil trapped due to viscous fingering, gravity segregation, and capillary forces.[151] Enhanced oil recovery (EOR), or tertiary recovery, targets residual oil bypassed by prior methods, potentially increasing overall recovery to 30 to 60 percent of OOIP through mobility control, interfacial tension reduction, and wettability alteration.[145] Thermal EOR, suited for heavy oils, employs steam injection to lower viscosity or in-situ combustion to generate heat via controlled burning.[152] Chemical EOR uses polymers for viscosity enhancement, surfactants for tension reduction, or alkaline agents for soap generation to liberate trapped oil.[153] Miscible gas injection, often with CO2 or hydrocarbons, achieves near-complete miscibility to minimize trapping, adding 4 to 15 percentage points beyond secondary recovery.[154] Global average recovery from conventional reservoirs stands at approximately 35 percent, with EOR implementation varying by economic viability and reservoir suitability.[152] Modern extraction increasingly incorporates advanced drilling techniques, particularly for unconventional tight oil and shale reservoirs, where vertical wells prove inefficient. Horizontal drilling extends the wellbore laterally through the pay zone, maximizing reservoir contact, often paired with hydraulic fracturing to create conductive fractures in low-permeability rock.[155][156] This combination has enabled recovery from formations previously uneconomic, though initial recovery rates remain low at 5 to 10 percent due to complex fracture networks and rapid decline curves.[157] Offshore extraction employs similar principles but utilizes subsea completions, floating platforms, and directional drilling to access deepwater reservoirs, with recovery enhanced by managed pressure drilling and real-time monitoring.[158]Refining, Safety, and Efficiency Improvements