Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cell (biology)

View on Wikipedia

| Cell | |

|---|---|

A eukaryotic cell as in animals (left) and a prokaryotic cell as in bacteria (right) | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D002477 |

| TH | H1.00.01.0.00001 |

| FMA | 686465 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all forms of life or organisms. The term comes from the Latin word cellula meaning 'small room'. A biological cell basically consists of a semipermeable cell membrane enclosing cytoplasm that contains genetic material. Most cells are only visible under a microscope. Except for highly-differentiated cell types (examples include red blood cells and gametes) most cells are capable of replication, and protein synthesis. Some types of cell are motile. Cells emerged on Earth about four billion years ago.

All organisms are grouped into prokaryotes, and eukaryotes. Prokaryotes are single-celled, and include archaea, and bacteria. Eukaryotes can be single-celled or multicellular, and include protists, plants, animals, most types of fungi, and some species of algae. All multicellular organisms are made up of many different types of cell. The diploid cells that make up the body of a plant or animal are known as somatic cells, and in animals excludes the haploid gametes.

Prokaryotic cells lack the membrane-bound nucleus present in eukaryotic cells, and instead have a nucleoid region. In eukaryotic cells the nucleus is enclosed in the nuclear membrane. Eukaryotic cells contain other membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria, which provide energy for cell functions, and chloroplasts, in plants that create sugars by photosynthesis. Other non-membrane-bound organelles may be proteinaceous such as the ribosomes present (though different) in both groups. A unique membrane-bound prokaryotic organelle the magnetosome has been discovered in magnetotactic bacteria.

Cells were discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665, who named them after their resemblance to cells in a monastery. Cell theory, developed in 1839 by Matthias Jakob Schleiden and Theodor Schwann, states that all organisms are composed of one or more cells, that cells are the fundamental unit of structure and function in all organisms, and that all cells come from pre-existing cells.

Types

[edit]

Organisms are broadly grouped into eukaryotes, and prokaryotes. Eukaryotic cells possess a membrane-bound nucleus, and prokaryotic cells lack a nucleus but have a nucleoid region.[1] Prokaryotes are single-celled organisms, whereas eukaryotes can be either single-celled or multicellular. Single-celled eukaryotes include microalgae such as diatoms. Multicellular eukaryotes include all animals, and plants, most fungi, and some species of algae.[2][3][4]

Prokaryotes

[edit]

All prokaryotes are single-celled and include bacteria and archaea, two of the three domains of life.[5] Prokaryotic cells were likely the first form of life on Earth,[6][7] characterized by having vital biological processes including cell signaling. They are simpler and smaller than eukaryotic cells, lack a nucleus, and the other usually present membrane-bound organelles.[8] Prokaryotic organelles are simple structures typically non-membrane-bound.[9]

Bacteria

[edit]Bacteria are enclosed in a cell envelope, that protects the interior from the exterior.[10] It generally consists of a plasma membrane covered by a cell wall which, for some bacteria, is covered by a third gelatinous layer called a bacterial capsule. The capsule may be polysaccharide as in pneumococci, meningococci or polypeptide as Bacillus anthracis or hyaluronic acid as in streptococci. Mycoplasma only possess the cell membrane.[11] The cell envelope gives rigidity to the cell and separates the interior of the cell from its environment, serving as a protective mechanical and chemical filter.[12] The cell wall consists of peptidoglycan and acts as an additional barrier against exterior forces.[13][12] The cell wall acts to protect the cell mechanically and chemically from its environment, and is an additional layer of protection to the cell membrane. It also prevents the cell from expanding and bursting (cytolysis) from osmotic pressure due to a hypotonic environment.[14]

The DNA of a bacterium typically consists of a single circular chromosome that is in direct contact with the cytoplasm in a region called the nucleoid. Some bacteria contain multiple circular or even linear chromosomes.[15][16][17] The cytoplasm also contains ribosomes and various inclusions where transcription takes place alongside translation.[18][19] Extrachromosomal DNA as plasmids, are usually circular and encode additional genes, such as those of antibiotic resistance.[20] Linear bacterial plasmids have been identified in several species of spirochete bacteria, including species of Borrelia which causes Lyme disease.[21] The prokaryotic cytoskeleton in bacteria is involved in the maintenance of cell shape, polarity and cytokinesis.[22]

Compartmentalization is a feature of eukaryotic cells but some species of bacteria, have protein-based organelle-like microcompartments such as gas vesicles, and carboxysomes, and encapsulin nanocompartments.[23][24][25][26] Certain membrane-bound prokaryotic organelles have also been discovered. They include the magnetosome of magnetotactic bacteria,[24] and the anammoxosome of anammox bacteria.[27][28]

Cell-surface appendages can include flagella, and pili, protein structures that facilitate movement and communication between cells.[29] The flagellum stretches from the cytoplasm through the cell membrane and extrudes through the cell wall.[30] Fimbriae are short attachment pili, the other type of pilus is the longer conjugative type.[31] Fimbriae are formed of an antigenic protein called pilin, and are responsible for the attachment of bacteria to specific receptors on host cells. [32]

Most prokaryotes are the smallest of all organisms, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm in diameter.[33] The largest bacterium known, Thiomargarita magnifica, is visible to the naked eye with an average length of 1 cm, but can be as much as 2 cm[34] [35]

Archaea

[edit]Archaea are enclosed in a cell envelope consisting of a plasma membrane and a cell wall. An exception to this is the Thermoplasma that only has the cell membrane.[11] The cell membranes of archaea are unique, consisting of ether-linked lipids. The prokaryotic cytoskeleton has homologues of eukaryotic actin and tubulin.[22] A unique form of metabolism in the archaean is methanogenesis. Their cell-surface appendage equivalent of the flagella is the differently structured and unique archaellum.[36][31] The DNA is contained in a circular chromosome in direct contact with the cytoplasm, in a region known as the nucleoid. Ribosomes are also found freely in the cytoplasm, or attached to the cell membrane where DNA processing takes place.[18][37]

The archaea are noted for their extremophile species, and many are selectively evolved to thrive in extreme heat, cold, acidic, alkaline, or high salt conditions.[38] There are no known archaean pathogens.[39]

Eukaryotes

[edit]Eukaryotes can be single-celled, as in diatoms (microscopic algae), or multicellular. Animals, plants, most fungi, and some algae are multicellular.[40] Eukaryotes are distinguished by the presence of a membrane-bound nucleus.[41] The nucleus gives the eukaryote its name, which means "true nut" or "true kernel", where "nut" means the nucleus.[42] Eukaryotic cells can be 2 to 1000 times larger in diameter than a typical prokaryote.[43]

| Property | Archaea | Bacteria | Eukaryota |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell membrane | Ether-linked lipids | Ester-linked lipids | Ester-linked lipids |

| Cell wall | Glycoprotein, or S-layer; rarely pseudopeptidoglycan | Peptidoglycan, S-layer, or no cell wall | Various structures |

| Gene structure | Circular chromosomes, similar translation and transcription to Eukaryota | Circular chromosomes, unique translation and transcription | Multiple, linear chromosomes, but translation and transcription similar to Archaea |

| Internal cell structure | No membrane-bound organelles (?[44]) or nucleus | No membrane-bound organelles or nucleus | Membrane-bound organelles and nucleus |

| Metabolism[45] | Various, including diazotrophy, with methanogenesis unique to Archaea | Various, including photosynthesis, aerobic and anaerobic respiration, fermentation, diazotrophy, and autotrophy | Photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and fermentation; no diazotrophy |

| Reproduction | Asexual reproduction, horizontal gene transfer | Asexual reproduction, horizontal gene transfer | Sexual and asexual reproduction |

| Protein synthesis initiation | Methionine | Formylmethionine | Methionine |

| RNA polymerase | One | One | Many |

| EF-2/EF-G | Sensitive to diphtheria toxin | Resistant to diphtheria toxin | Sensitive to diphtheria toxin |

Multicellular organisms are made up of many different types of cell known overall as somatic cells.[46] Typical plant cells include parenchyma cells including transfer cells, and collenchyma cells. Animal cells include all those that make up the four main tissue types of epithelium – a number of different epithelial cells; connective tissue such as osteoblasts in bone, and chondrocytes in cartilage; nervous tissue including different brain cells and nerves, and muscle tissue having different muscle cells.[1] The number of cells in these tissues vary with species. Studies on the human have estimated a total cell count at around 30 trillion cells (~36 trillion cells in the male, and ~28 trillion in the female).[47][48]

Eukaryotic cells

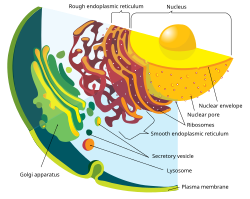

[edit]The cells of eukaryotes have a cell membrane that surrounds a gel-like cytoplasm; it contains the cytoskeleton, the cell nucleus, the endomembrane system, and organelles including mitochondria, and the Golgi apparatus.

Cell membrane

[edit]The cell membrane, or plasma membrane, is a selectively permeable membrane as an outer boundary of the cell that encloses the cytoplasm.[49] The membrane serves to separate and protect a cell from its surrounding environment and is made mostly from a lipid bilayer of phospholipids, which are amphiphilic (partly hydrophobic and partly hydrophilic), and is sometimes referred to as a fluid mosaic membrane.[50] Embedded within the cell membrane is a macromolecular structure called the porosome the universal secretory portal in cells and a variety of protein molecules that act as channels and pumps that move different molecules into and out of the cell.[18] The membrane is semi-permeable, and selectively permeable, in that it can either let a substance (molecule or ion) pass through freely, to a limited extent or not at all.[51] Cell surface receptors embedded in the membrane allow cells to detect external signaling molecules such as hormones.[52]

Underlying, and attached to the cell membrane is the cell cortex, the outermost part of the actin cytoskeleton.[53] Its thickness varies with cell type and physiology.

Cytoplasm

[edit]The membrane encloses the cytoplasm of the cell. It is made up of two main components, the cytosol, and the protein filaments that make up the cytoskeleton.[54][55] The cytosol is a gel-like substance made up of water, ions, and non-essential biomolecules. The network of filaments and microtubules of the cytoskeleton gives shape and support to the cell, and has a part in organising the cell components. The cytoplasm surrounds all the organelles of the cell.[54][55]

Cytoskeleton

[edit]The cytoskeleton acts to organize and maintain the cell's shape; anchors organelles in place; helps during endocytosis, the uptake of external materials by a cell, and cytokinesis, the separation of daughter cells after cell division; and moves parts of the cell in processes of growth and mobility. The cytoskeleton is composed of microtubules, intermediate filaments and microfilaments. In a neuron the intermediate filaments are known as neurofilaments. There are a great number of proteins associated with them, each controlling a cell's structure by directing, bundling, and aligning filaments. The outermost part of the cytoskeleton is the cell cortex, or actin cortex, a thin layer of cross-linked actomyosins.[53]

The centrosome is the cytoskeleton organizer in the animal cell that produces the microtubules of a cell—a key component of the cytoskeleton.[56] It directs the transport through the ER and the Golgi apparatus.[57] Centrosomes are composed of two centrioles which lie perpendicular to each other in which each has an organization like a cartwheel, which separate during cell division and help in the formation of the mitotic spindle.[56]

Organelles

[edit]Organelles are parts of the cell that are specialized for carrying out one or more vital functions.[18] There are several types of organelles in a cell held in the gelatinous cytosol of the cytoplasm that fills the cell and surrounds the organelles, forming 30%–50% of a cell volume.[58] Most organelles vary in size and/or number based on the growth of the host cell.[59]

Nucleus

[edit]

The cell nucleus is the largest organelle in the animal cell.[60] It houses the cell's chromosomes, and is the place where almost all DNA replication and RNA synthesis (transcription) occur. The nucleus is spherical and separated from the cytoplasm by a double membrane called the nuclear envelope, space between these two membrane is called perinuclear space. The nuclear envelope isolates and protects a cell's DNA from various molecules that could accidentally damage its structure or interfere with its processing. During processing, DNA is transcribed, or copied into a special RNA, called messenger RNA (mRNA). This mRNA is then transported out of the nucleus, where it is translated into a specific protein molecule. The nucleolus is a specialized region within the nucleus where ribosome subunits are assembled.[18] Cells use DNA for their long-term information storage that is encoded in its DNA sequence.[18] RNA is used for information transport (e.g., mRNA) and enzymatic functions (e.g., ribosomal RNA). Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules are used to add amino acids during protein translation.[61] Mitochondria have their own DNA (mitochondrial DNA).[62] The mitochondrial genome is a circular DNA molecule distinct from nuclear DNA. Although the mitochondrial DNA is very small compared to nuclear chromosomes,[18] it codes for 13 proteins involved in mitochondrial energy production and specific tRNAs.[63]

The DNA of each cell is its genetic material, and is organized in multiple linear molecules, called chromosomes, that are coiled around histone proteins and housed in the cell nucleus.[41][64] In humans, the nuclear genome is divided into 46 linear chromosomes, including 22 homologous chromosome pairs and a pair of sex chromosomes. The nucleus is a membrane-bound organelle. Other organelles in the cell have specific functions such as mitochondria which provide the cell's energy.[65]

Golgi apparatus

[edit]The Golgi apparatus processes and packages the macromolecules, such as proteins and lipids, that are synthesized by the cell. It is organized as a stack of plate-like structures known as cisternae.[66]

Mitochondria

[edit]Mitochondria generate energy for the cell. Mitochondria are self-replicating double membrane-bound organelles that occur in various numbers, shapes, and sizes in the cytoplasm of the cell.[18] Respiration occurs in the cell mitochondria, which generate the cell's energy by oxidative phosphorylation, using oxygen to release energy stored in cellular nutrients (typically pertaining to glucose) to generate ATP (aerobic respiration).[67] Mitochondria multiply by binary fission.[68]

Lysosomes

[edit]Lysosomes contain enzymes (acid hydrolases). They digest excess or worn-out organelles, food particles, and engulfed viruses or bacteria. Lysosomes are optimally active in an acidic environment. The cell could not house these destructive enzymes if they were not contained in a membrane-bound system.[18][69]

Peroxisomes

[edit]Peroxisomes have enzymes that rid the cell of toxic peroxides,

Vacuoles

[edit]Vacuoles sequester waste products. Some cells, most notably Amoeba, have contractile vacuoles, which can pump water out of the cell if there is too much water.[70]

Endomembrane system

[edit]

The endomembrane system consists of all the different internal membranes of the cell. These membranes are held in the cell's cytoplasm and divide the various organelles.

Endoplasmic reticulum

[edit]The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a transport network for molecules targeted for certain modifications and specific destinations, as compared to molecules that float freely in the cytoplasm. The ER has two forms: the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), which has ribosomes on its surface that secrete proteins into the ER, and the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER), which lacks ribosomes.[18]

A ribosome is a large complex of RNA and protein molecules.[18] They each consist of two subunits, one larger than the other, and act as an assembly line where RNA from the nucleus is used to synthesise proteins from amino acids. Ribosomes can be found either floating freely or bound to a membrane of the rough endoplasmatic reticulum.[71]

The smooth ER plays a role in calcium sequestration and release, and helps in synthesis of lipid.[72]

Cells of major eukaryote groups

[edit]Animal cells

[edit]

All the cells in an animal body develop from one totipotent diploid cell called a zygote. During the development of an animal, the cells differentiate into the specialised tissues and organs of the organism. (An exception is the simple sponge). The estimated cell count in a typical adult human body is around 30 trillion cells. Different groups of cells differentiate from the three germ layers. Differentiation results in structural or functional changes to the typical eukaryotic cell.

Some types of specialised cell are localised to a particular animal group. Vertebrates for example have specialised, structurally changed cells including muscle cells. The cell membrane of a skeletal muscle cell or of a cardiac muscle cell is termed the sarcolemma.[73] And the cytoplasm is termed the sarcoplasm. Skeletal muscle cells also become multinucleated. Populations of animal groups evolve to become distinct species, where sexual reproduction is isolated. The many species of vertebrates for example have other unique characteristics by way of additional specialised cells. In some species of electric fish for example modified muscle cells or nerve cells have specialised to become electerocytes capable of creating and storing electrical energy for future release, as in stunning prey, or use in electrolocation.[74] These are large flat cells in the electric eel, and electric ray in which thousands are stacked into an electric organ comparable to a voltaic pile.[75]

Organelles are parts of the cell that are specialized for carrying out one or more vital functions, analogous to the organs of the human body (such as the heart, lung, and kidney, with each organ performing a different function).[18] In addition to the organelles shared by all eukaryotes, animal cells often have cilia or flagella.[76][77] Many animal cells are ciliated and most cells except red blood cells have primary cilia. Primary cilia play important roles in chemosensation and mechanosensation.[78] Each cilium may be "viewed as a sensory cellular antennae that coordinates a large number of cellular signaling pathways, sometimes coupling the signaling to ciliary motility or alternatively to cell division and differentiation."[79] Ciliated cells in the respiratory epithelium play an important role in the movement of mucus. Some animal cells have flagella such as flagellated protists and sperm cells, that enable movement.[76] Invertebrate planarians have ciliated excretory flame cells.[80] Other excretory cells also found in planarians are solenocytes that are long and flagellated.

Plant cells

[edit]

Other types of organelle specific to plant cells, are pigment-containing plastids, especially chloroplasts that contain chlorophyll, and large water-storing vacuoles.

Chloroplasts capture the sun's energy to make carbohydrates through photosynthesis.[81]Chromoplasts contain fat-soluble carotenoid pigments such as orange carotene and yellow xanthophylls which helps in synthesis and storage. Leucoplasts are non-pigmented plastids and helps in storage of nutrients.[82] Plastids divide by binary fission. Vacuoles in plant cells store water. They are liquid filled spaces surrounded by a membrane.[83]The vacuoles of plant cells are usually larger than those of animal cells.They are described as liquid filled spaces and are surrounded by a membrane.[83] Vacuoles of plant cells are surrounded by a membrane which transports ions against concentration gradients.[84]

Algal cells

[edit]Algae members are photoautotrophs able to use photosynthesis to produce energy. Photosynthesis is made possible by the use of plastids, organelles in the cytoplasm known as chloroplasts. Algal photoautotrophs include red algae.[85]

Alginate is a polysaccharide found in the matrix of the cell walls of brown algae, and have many important uses in the food industry, and in pharmacology.[86]

Fungal cells

[edit]The cells of fungi have in addition to the shared eukaryotic organelles a spitzenkörper in their endomembrane system, associated with hyphal tip growth. It is a phase-dark body that is composed of an aggregation of membrane-bound vesicles containing cell wall components, serving as a point of assemblage and release of such components intermediate between the Golgi and the cell membrane. The spitzenkörper is motile and generates new hyphal tip growth as it moves forward.[87]

Protist cells

[edit]The cells of protists may be bounded only by a cell membrane, or may in addition have a cell wall, or may be covered by a pellicle (in ciliates), a test (in testate amoebae), or a frustule (in diatoms).

Some protists such as amoebae may feed on other organisms and ingest food by phagocytosis. Vacuoles known as phagosomes in the cytoplasm may be used to draw in and incorporate the captured particles. Other types of protists are photoautotrophs, providing themselves with energy by photosynthesis.[88] Most protists are motile and generate movement with cilia, flagella, or pseudopodia.[88]

Physiology

[edit]

Replication

[edit]

During cell division, part of the cell cycle, a single cell, the mother cell divides into two daughter cells. This leads to growth in multicellular organisms (the growth of tissue) and to procreation (vegetative reproduction) in unicellular organisms. Prokaryotic cells divide by binary fission, while eukaryotic cells usually undergo a process of nuclear division, called mitosis, followed by division of the cell, called cytokinesis. A diploid cell may undergo meiosis to produce haploid cells, usually four. Haploid cells serve as gametes in multicellular organisms, fusing to form new diploid cells.[89]

DNA replication, or the process of duplicating a cell's genome,[18] always happens when a cell divides through mitosis or binary fission.[89] This occurs during the S (synthesis) phase of the cell cycle.

In meiosis, the DNA is replicated only once, while the cell divides twice. DNA replication only occurs before meiosis I. DNA replication does not occur when the cells divide the second time, in meiosis II.[90] Replication, like all cellular activities, requires specialized proteins.[18]

DNA repair

[edit]All cells contain enzyme systems that scan for DNA damage and carry out repair. Diverse repair processes have evolved in all organisms. Repair is vital to maintain DNA integrity, avoid cell death and errors of replication that could lead to mutation. Repair processes include nucleotide excision repair, DNA mismatch repair, non-homologous end joining of double-strand breaks, recombinational repair and light-dependent repair (photoreactivation).[91]

Growth and metabolism

[edit]Between successive cell divisions, cells grow through the functioning of cellular metabolism. Cell metabolism is the process by which individual cells process nutrient molecules. Metabolism has two distinct divisions: catabolism, in which the cell breaks down complex molecules to produce energy and reducing power, and anabolism, in which the cell uses energy and reducing power to construct complex molecules and perform other biological functions.[92]

Complex sugars can be broken down into simpler sugar molecules called monosaccharides such as glucose. Once inside the cell, glucose is broken down to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP),[18] a molecule that possesses readily available energy, through two different pathways. In plant cells, chloroplasts create sugars by photosynthesis, using the energy of light to join molecules of water and carbon dioxide.[93]

Protein synthesis

[edit]Cells are capable of synthesizing new proteins, which are essential for the modulation and maintenance of cellular activities. This process involves the formation of new protein molecules from amino acid building blocks based on information encoded in DNA/RNA. Protein synthesis generally consists of two major steps: transcription and translation.[61]

Transcription is the process where genetic information in DNA is used to produce a complementary RNA strand. This RNA strand is then processed to give messenger RNA (mRNA), which is free to migrate into the cytoplasm. mRNA molecules bind to protein-RNA complexes called ribosomes located in the cytosol, where they are translated into polypeptide sequences. The ribosome mediates the formation of a polypeptide sequence based on the mRNA sequence. The mRNA sequence directly relates to the polypeptide sequence by binding to transfer RNA (tRNA) adapter molecules in binding pockets within the ribosome.[61] The new polypeptide then folds into a functional three-dimensional protein molecule.

Motility

[edit]Unicellular organisms can move in order to find food or escape predators. Common mechanisms of motion include flagella and cilia.[31]

In multicellular organisms, cells can move during processes such as wound healing, the immune response and cancer metastasis. For example, in wound healing in animals, white blood cells move to the wound site to kill the microorganisms that cause infection. Cell motility involves many receptors, crosslinking, bundling, binding, adhesion, motor and other proteins.[94] The process is divided into three steps: protrusion of the leading edge of the cell, adhesion of the leading edge and de-adhesion at the cell body and rear, and cytoskeletal contraction to pull the cell forward. Each step is driven by physical forces generated by unique segments of the cytoskeleton.[95][94]

Navigation, control and communication

[edit]In August 2020, scientists described one way cells—in particular cells of a slime mold and mouse pancreatic cancer-derived cells—are able to navigate efficiently through a body and identify the best routes through complex mazes: generating gradients after breaking down diffused chemoattractants which enable them to sense upcoming maze junctions before reaching them, including around corners.[96][97][98]

Death

[edit]Cell death is the event of a biological cell ceasing to carry out its functions. This may be the result of the natural process of old cells dying and being replaced by new ones, as in programmed cell death, or may result from factors such as diseases, localized injury, exposure to a toxic substance, or the death of the host organism. Apoptosis or Type I cell-death, and autophagy or Type II cell-death are both forms of programmed cell death, while necrosis is a non-physiological process that occurs as a result of infection or injury.[99][100]

Cell ancestry traces back in an unbroken lineage for over 3 billion years. The immortality of a cell lineage depends on the maintenance of cell division potential,[101] which may be lost because of cell damage, terminal differentiation as occurs in nerve cells, or programmed cell death during development. Maintenance of division potential over successive generations depends on the avoidance and the accurate repair of cellular damage, particularly DNA damage. Sexual processes provide an opportunity for effective repair of DNA damage in the germ line by homologous recombination.[101][102]

Multicellularity

[edit]Cell differentiation

[edit]

Multicellular organisms are organisms that consist of more than one cell, in contrast to single-celled organisms.[103] Microorganisms cloned from a single cell can form visible microbial colonies. A microbial consortium of two or more species of microorganisms can form a biofilm community,[104] such as dental plaque. The cell-to-cell adhesion found in microbial colonies may have been the first evolutionary step toward more complex multicellular organisms.[105]

In complex multicellular organisms, cells specialize into different cell types that are adapted to particular functions.[106] In animals, major cell types include skin cells, muscle cells, neurons, blood cells, fibroblasts, stem cells, and others. Cell types differ both in appearance and function, yet are genetically identical. Cells are able to be of the same genotype but of different cell type due to the differential expression of the genes they contain.[107]

Most distinct cell types arise from a single totipotent cell, called a zygote, that differentiates into hundreds of different cell types during the course of development. Differentiation of cells is driven by different environmental cues (such as cell–cell interaction) and intrinsic differences (such as those caused by the uneven distribution of molecules during division).[108]

Signaling

[edit]Cell signaling is the process by which a cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Typically, the signaling process involves three components: the first messenger (the ligand), the receptor, and the signal itself.[109] Most cell signaling is chemical in nature, and can occur with neighboring cells or more distant targets. Signal receptors are complex proteins or tightly bound multimer of proteins, located in the plasma membrane or within the interior.[110]

Each cell is programmed to respond to specific extracellular signal molecules, and this process is the basis of development, tissue repair, immunity, and homeostasis. Individual cells are able to manage receptor sensitivity including turning them off, and receptors can become less sensitive when they are occupied for long durations.[110] Errors in signaling interactions may cause diseases such as cancer, autoimmunity, and diabetes.[111]

Origin of multicellularity

[edit]Multicellularity has evolved independently at least 25 times,[112] including in some prokaryotes, like cyanobacteria, myxobacteria, actinomycetes, or Methanosarcina. However, complex multicellular organisms evolved only in six eukaryotic groups: animals, fungi, brown algae, red algae, green algae, and plants.[113] It evolved repeatedly for plants (Chloroplastida), once or twice for animals, once for brown algae, and perhaps several times for fungi, slime molds, and red algae.[114] Multicellularity may have evolved from colonies of interdependent organisms, from cellularization, or from organisms in symbiotic relationships.[115]

The first evidence of multicellularity is from cyanobacteria-like organisms that lived between 3 and 3.5 billion years ago.[112] Other early fossils of multicellular organisms include the contested Grypania spiralis and the fossils of the black shales of the Palaeoproterozoic Francevillian Group Fossil B Formation in Gabon.[116]

The evolution of multicellularity from unicellular ancestors has been replicated in the laboratory, in evolution experiments using predation as the selective pressure.[112]

Origins

[edit]The origin of cells has to do with the origin of life, which began the history of life on Earth.

Origin of life

[edit]

Small molecules needed for life may have been carried to Earth on meteorites, created at deep-sea vents, or synthesized by lightning in a reducing atmosphere. There is little experimental data defining what the first self-replicating forms were. RNA may have been the earliest self-replicating molecule, as it can both store genetic information and catalyze chemical reactions.[117] This process required an enzyme to catalyze the RNA reactions, which may have been the early peptides that formed in hydrothermal vents.[118]

Cells emerged around 4 billion years ago.[119][120] The first cells were most likely heterotrophs. The early cell membranes were probably simpler and more permeable than modern ones, with only a single fatty acid chain per lipid. Lipids spontaneously form bilayered vesicles in water, and could have preceded RNA.[121][122]

First eukaryotes

[edit]

Eukaryotic cells were created some 2.2 billion years ago in a process called eukaryogenesis. This is widely agreed to have involved symbiogenesis, in which archaea and bacteria came together to create the first eukaryotic common ancestor.[123] However, the sequence of the steps involved has been disputed.[citation needed] It evolved into a population of single-celled organisms that included the last eukaryotic common ancestor, gaining capabilities along the way.[124][125]

This cell had a new level of complexity and capability, with a nucleus[126][124] and facultatively aerobic mitochondria.[123] It featured at least one centriole and cilium, sex (meiosis and syngamy), peroxisomes, and a dormant cyst with a cell wall of chitin and/or cellulose.[127][125] The last eukaryotic common ancestor gave rise to the eukaryotes' crown group, containing the ancestors of animals, fungi, plants, and a diverse range of single-celled organisms.[128][129] The plants were created around 1.6 billion years ago with a second episode of symbiogenesis that added chloroplasts, derived from cyanobacteria.[123]

History of research

[edit]

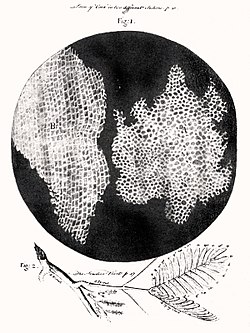

In 1665, Robert Hooke examined a thin slice of cork under his microscope, and saw a structure of small enclosures. He wrote "I could exceeding plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a honeycomb, but that the pores of it were not regular".[130] To further support his theory, Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann studied cells of both animal and plants. What they discovered were significant differences between the two types of cells. This put forth the idea that cells were fundamental to both plants and animals.[131]

- 1632–1723: Antonie van Leeuwenhoek taught himself to make lenses, constructed basic optical microscopes and drew protozoa, such as Vorticella from rain water, and bacteria from his own mouth.[132]

- 1665: Robert Hooke discovered cells in cork, then in living plant tissue using an early microscope. In his book Micrographia he coined the term cell (from Latin cellula, meaning "small room") since they resembled the cells of a monastery[133][134][135][136][132]

- 1839: Theodor Schwann[137] and Matthias Jakob Schleiden elucidated the principle that plants and animals are made of cells, concluding that cells are a common unit of structure and development, founding the cell theory.[138][139]

- 1855: Rudolf Virchow stated that new cells come from pre-existing cells by cell division (omnis cellula ex cellula).

- 1931: Ernst Ruska built the first transmission electron microscope at the University of Berlin.[140] By 1935, he had built an electron microscope with twice the resolution of a light microscope, revealing previously unresolvable organelles.

- 1981: Lynn Margulis published Symbiosis in Cell Evolution detailing how eukaryotic cells were created by symbiogenesis.[141]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Cooper, Geoffrey M. (2000). "The Origin and Evolution of Cells". The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "Prokaryote structure". khanacademy. Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ Knoll, Andrew H. (2011). "The Multiple Origins of Complex Multicellularity". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 39: 217–239. Bibcode:2011AREPS..39..217K. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100209.

- ^ "24.1B: Fungi Cell Structure and Function". Biology LibreTexts. 15 July 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2025.

- ^ Cole, Laurence A. (2016-01-01), Cole, Laurence A. (ed.), "Chapter 13 - Evolution of Chemical, Prokaryotic, and Eukaryotic Life", Biology of Life, Academic Press, pp. 93–99, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-809685-7.00013-7, ISBN 978-0-12-809685-7, retrieved 2025-08-16

- ^ "Evolutionary History of Prokaryotes". courses.lumenlearning.com. Biology for Majors II. Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ Poole, Anthony; Jeffares, Daniel; Penny, David (1999). "Early evolution: prokaryotes, the new kids on the block". BioEssays. 21 (10): 880–889. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199910)21:10<880::AID-BIES11>3.0.CO;2-P. ISSN 1521-1878. PMID 10497339.

- ^ Fowler, Samantha; Roush, Rebecca; Wise, James (2013-04-25). "3.2 Comparing Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells - Concepts of Biology | OpenStax". openstax.org. Retrieved 2025-08-22.

- ^ Grant, Carly R.; et al. (October 2018). "Organelle Formation in Bacteria and Archaea". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 34: 217–238. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060908. PMID 30113887.

- ^ Silhavy, Thomas J.; Kahne, Daniel; Walker, Suzanne (2010-05-01). "The Bacterial Cell Envelope". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (5) a000414. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 2857177. PMID 20452953.

- ^ a b Barton, Larry L. (2005). Structural and Functional Relationships in Prokaryotes. SpringerLink: Springer e-Books. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-387-27125-5.

- ^ a b Fuertes-Rabanal, María; et al. (July 2, 2025). "Cell walls: a comparative view of the composition of cell surfaces of plants, algae, and microorganisms". Journal of Experimental Botany. 76 (10): 2614–2645. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae512. PMC 12223506. PMID 39705009.

- ^ Seltmann, Guntram; Holst, Otto (2013). The Bacterial Cell Wall. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-662-04878-8.

- ^ Prasad, Krishna Kant; Prasad, Nooralabettu Krishna (2010). Downstream Process Technology: A New Horizon In Biotechnology. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-81-203-4040-4.

- ^ Egan, Elizabeth S.; Fogel, Michael A.; Waldor, Matthew K. (2005). "MicroReview: Divided genomes: negotiating the cell cycle in prokaryotes with multiple chromosomes". Molecular Microbiology. 56 (5): 1129–1138. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04622.x. PMID 15882408.

- ^ "Genome Packaging in Prokaryotes | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- ^ "The difference between nucleus and nucleoid". BYJUS. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o

This article incorporates public domain material from "What Is a Cell?". Science Primer. NCBI. 30 March 2004. Archived from the original on 2009-12-08. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

This article incorporates public domain material from "What Is a Cell?". Science Primer. NCBI. 30 March 2004. Archived from the original on 2009-12-08. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ "7.6C: Prokaryotic Transcription and Translation Are Coupled". Biology LibreTexts. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ Henkin, Tina M.; Peters, Joseph E. (2020). Snyder and Champness Molecular Genetics of Bacteria. ASM Books (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 181–189. ISBN 978-1-55581-975-0.

- ^ "Karyn's Genomes: Borrelia burgdorferi". 2can on the EBI-EMBL database. European Bioinformatics Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- ^ a b Erickson HP (February 2017). "The discovery of the prokaryotic cytoskeleton: 25th anniversary". Mol Biol Cell. 28 (3): 357–358. doi:10.1091/mbc.E16-03-0183. PMC 5341718. PMID 28137947.

- ^ McDowell HB, Hoiczyk E (March 2022). "Bacterial Nanocompartments: Structures, Functions, and Applications". J Bacteriol. 204 (3) e00346-21: e0034621. doi:10.1128/JB.00346-21. PMC 8923211. PMID 34606372.

- ^ a b Murat, D; Byrne, M; Komeili, A (October 2010). "Cell biology of prokaryotic organelles". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (10) a000422. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000422. PMC 2944366. PMID 20739411.

- ^ Stewart, Katie L.; Stewart, Andrew M.; Bobik, Thomas A. (2020-10-06). "Prokaryotic Organelles: Bacterial Microcompartments in E. coli and Salmonella". EcoSal Plus. 9 (1) 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP–0025–2019. doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0025-2019. PMC 7552817. PMID 33030141.

- ^ Adamiak N, Krawczyk KT, Locht C, Kowalewicz-Kulbat M (2021). "Archaeosomes and Gas Vesicles as Tools for Vaccine Development". Front Immunol. 12 746235. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.746235. PMC 8462270. PMID 34567012.

- ^ de Almeida, NM; Neumann, S; Mesman, RJ; Ferousi, C; Keltjens, JT; Jetten, MS; Kartal, B; van Niftrik, L (July 2015). "Immunogold Localization of Key Metabolic Enzymes in the Anammoxosome and on the Tubule-Like Structures of Kuenenia stuttgartiensis". Journal of Bacteriology. 197 (14): 2432–41. doi:10.1128/JB.00186-15. PMC 4524196. PMID 25962914.

- ^ Saier Jr., Milton H.; Bogdanov, Mikhail V. (2013). "Membranous Organelles in Bacteria". Microbial Physiology. 23 (1–2): 5–12. doi:10.1159/000346496. PMID 23615191.

- ^ Kim, K. W. (2017). "Electron microscopic observations of prokaryotic surface appendages". Journal of Microbiology. 55 (12): 919–926. doi:10.1007/s12275-017-7369-4. PMID 29214488.

- ^ Cohen-Bazire, Germaine; London, Jack (August 1967). "Basal Organelles of Bacterial Flagella". Journal of Bacteriology. 94 (2): 458–465. doi:10.1128/jb.94.2.458-465.1967. PMC 315060. PMID 6039362.

- ^ a b c Beeby, Morgan; et al. (May 2020). "Propulsive nanomachines: the convergent evolution of archaella, flagella and cilia". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 44 (3): 253–304. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuaa006. PMID 32149348.

- ^ Wilson, Brenda A.; et al. (2020). Bacterial Pathogenesis: A Molecular Approach. ASM Books (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-55581-941-5.

- ^ Black, Jacquelyn G. (2004). Microbiology. New York Chichester: Wiley. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-471-42084-2.

- ^ Volland, Jean-Marie; et al. (June 24, 2022). "A centimeter-long bacterium with DNA contained in metabolically active, membrane-bound organelles". Science. 376 (6600): 1453–1458. Bibcode:2022Sci...376.1453V. bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.02.16.480423. doi:10.1126/science.abb3634. eISSN 1095-9203. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35737788. S2CID 249990020.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth. "Largest bacterium ever discovered has unexpectedly complex cells". Science. science.org. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ van Wolferen, Marleen; Pulschen, Andre Arashiro; Baum, Buzz; Gribaldo, Simonetta; Albers, Sonja-Verena (November 2022). "The cell biology of archaea". Nature Microbiology. 7 (11): 1744–1755. doi:10.1038/s41564-022-01215-8. ISSN 2058-5276. PMC 7613921. PMID 36253512.

- ^ Ménétret, Jean-François; Schaletzky, Julia; Clemons, William M.; et al. (December 2007). "Ribosome binding of a single copy of the SecY complex: implications for protein translocation" (PDF). Molecular Cell. 28 (6): 1083–1092. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.034. PMID 18158904. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ Rampelotto, Pabulo Henrique (2013). "Extremophiles and Extreme Environments". Life. 3 (3): 482–485. Bibcode:2013Life....3..482R. doi:10.3390/life3030482. PMC 4187170. PMID 25369817.

- ^ Duller S, Moissl-Eichinger C (August 2024). "Archaea in the Human Microbiome and Potential Effects on Human Infectious Disease". Emerg Infect Dis. 30 (8): 1505–13. doi:10.3201/eid3008.240181. PMC 11286065. PMID 39043386.

- ^ Lodé, Thierry (2012-10-19). "For Quite a Few Chromosomes More: The Origin of Eukaryotes…". Journal of Molecular Biology. 423 (2): 135–142. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2012.07.005. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 22796299.

- ^ a b Visible Body, part of Cengage Learning. "Eukaryotic Chromosomes". www.visiblebody.com. Retrieved 2025-09-11.

- ^ "More on Eukaryote Morphology". ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2025-09-03.

- ^ Bartee, Lisa; Shriner, Walter; Creech, Catherine (2017). "Comparing Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells". OpenOregon Educational Resources.

- ^ Heimerl T, Flechsler J, Pickl C, Heinz V, Salecker B, Zweck J, Wanner G, Geimer S, Samson RY, Bell SD, Huber H, Wirth R, Wurch L, Podar M, Rachel R (13 June 2017). "A Complex Endomembrane System in the Archaeon Ignicoccus hospitalis Tapped by Nanoarchaeum equitans". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8 1072. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01072. PMC 5468417. PMID 28659892.

- ^ Jurtshuk P (1996). "Bacterial Metabolism". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. PMID 21413278.

- ^ "Somatic Cells". www.genome.gov. Retrieved 19 September 2025.

- ^ Hatton, Ian A.; Galbraith, Eric D.; Merleau, Nono S. C.; Miettinen, Teemu P.; Smith, Benjamin McDonald; Shander, Jeffery A. (2023-09-26). "The human cell count and size distribution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (39) e2303077120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12003077H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2303077120. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 10523466. PMID 37722043.

- ^ "Human Cell data". humancelltreemap.mis.mpg.de. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ "Inside the Cell" (PDF). publications.nigms.nih.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ Singer, S. J.; Nicolson, Garth L. (February 18, 1972). "The Fluid Mosaic Model of the Structure of Cell Membranes: Cell membranes are viewed as two-dimensional solutions of oriented globular proteins and lipids". Science. 175 (4023): 720–731. doi:10.1126/science.175.4023.720. PMID 4333397.

- ^ Stillwell, William (April 26, 2013). "Membrane Transport". An Introduction to Biological Membranes. pp. 305–337. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52153-8.00014-3. ISBN 978-0-444-52153-8. PMC 7182113.

- ^ Guyton, Arthur C.; Hall, John E. (2016). Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 930–937. ISBN 978-1-4557-7005-2. OCLC 1027900365.

- ^ a b Zhu H, Miao R, Wang J, Lin M (March 2024). "Advances in modeling cellular mechanical perceptions and responses via the membrane-cytoskeleton-nucleus machinery". Mechanobiol Med. 2 (1) 100040. doi:10.1016/j.mbm.2024.100040. PMC 12082147. PMID 40395451.

- ^ a b "Cytoplasm, Cytosol and Cytoskeleton". Journal of Clinical Research and Medicine. 5 (5). 28 September 2022. doi:10.31038/JCRM.2022552.

- ^ a b Alberts, Bruce (2015). Molecular biology of the cell (6th ed.). New York: Garland science, Taylor and Francis group. p. 642. ISBN 978081534464-3.

- ^ a b Prigent, Claude; Uzbekov, Rustem (2022). "Duplication and Segregation of Centrosomes during Cell Division". Cells. 11 (15) 2445. doi:10.3390/cells11152445. PMC 9367774. PMID 35954289.

- ^ Gurel, Pinar S.; et al. (July 21, 2014). "Connecting the Cytoskeleton to the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi". Current Biology. 24 (14): R660 – R672. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2015.03.021. PMC 4678951. PMID 25869000.

- ^ Vekilov, P. G.; et al. (2008). "Metastable mesoscopic phases in concentrated protein solutions". In Franzese, Giancarlo; Rubi, Miguel (eds.). Aspects of Physical Biology: Biological Water, Protein Solutions, Transport and Replication. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 752. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-3-540-78764-8.

- ^ Marshall, Wallace F. (2020). "Scaling of Subcellular Structures". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 36: 219–236. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-020520-113246. PMC 8562892. PMID 32603615.

- ^ Khan, Yusuf S.; Farhana, Aisha (2025). "Histology, Cell". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ a b c Colville, Thomas P.; Bassert, Joanna M. (2015). Clinical Anatomy and Physiology for Veterinary Technicians (3rd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-0-323-22793-3.

- ^ Allen, John F. (February 14, 2003). "Why chloroplasts and mitochondria contain genomes". Comparative and Functional Genomics. 4 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1002/cfg.245. PMC 2447392. PMID 18629105.

- ^ Boore, Jeffrey L. (April 1999). "Animal mitochondrial genomes Open Access". Nucleic Acids Research. 27 (8): 1767–1780. doi:10.1093/nar/27.8.1767. PMC 148383. PMID 10101183.

- ^ Visible Body, part of Cengage Learning. "Eukaryotic vs. Prokaryotic Chromosomes". www.visiblebody.com. Retrieved 2025-09-11.

- ^ Gabaldón, Toni; Pittis, Alexandros A. (2015). "Origin and evolution of metabolic sub-cellular compartmentalization in eukaryotes". Biochimie. 119: 262–268. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2015.03.021. PMC 4678951. PMID 25869000.

- ^ Short, Ben; Barr, Francis A. (August 14, 2000). "The Golgi apparatus". Current Biology. 10 (16): R583 – R585. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.R583S. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00644-8. PMID 10985372.

- ^ Beard, Daniel A. (September 9, 2005). "A Biophysical Model of the Mitochondrial Respiratory System and Oxidative Phosphorylation". PLOS Computational Biology. 1 (4): e36. Bibcode:2005PLSCB...1...36B. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010036. PMC 1201326. PMID 16163394.

- ^ Steven, Alasdair; et al. (2016). Molecular Biology of Assemblies and Machines. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-134-98282-0.

- ^ Soto, Ubaldo; et al. (1993). "Peroxisomes and Lysosomes". In LeBouton, Albert V. (ed.). Molecular & Cell Biology of the Liver. CRC Press. pp. 181–211. ISBN 978-0-8493-8891-0.

- ^ Pappas, George D.; Brandt, Philip W. (1958). "The Fine Structure of the Contractile Vacuole in Ameba". The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 4 (4): 485–488. doi:10.1083/jcb.4.4.485. ISSN 0095-9901. JSTOR 1603216. PMC 2224495. PMID 13563556.

- ^ Ménétret, Jean-François; Schaletzky, Julia; Clemons, William M.; et al. (December 2007). "Ribosome binding of a single copy of the SecY complex: implications for protein translocation" (PDF). Molecular Cell. 28 (6): 1083–1092. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.034. PMID 18158904. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ Pavelka, M.; Roth, J. (2010). "Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum". Functional Ultrastructure. Vienna: Springer. pp. 42–43. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-99390-3_23. ISBN 978-3-211-99389-7.

- ^ Roberts, MD; Haun, CT; Vann, CG; Osburn, SC; Young, KC (2020). "Sarcoplasmic Hypertrophy in Skeletal Muscle: A Scientific "Unicorn" or Resistance Training Adaptation?". Frontiers in Physiology. 11 816. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.00816. PMC 7372125. PMID 32760293.

- ^ Markham MR (July 2013). "Electrocyte physiology: 50 years later". J Exp Biol. 216 (Pt 13): 2451–8. Bibcode:2013JExpB.216.2451M. doi:10.1242/jeb.082628. PMID 23761470.

- ^ Mauro A (April 1969). "The role of the Voltaic pile in the Galvani-Volta controversy concerning animal vs. metallic electricity". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 24 (2): 140–50. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xxiv.2.140. PMID 4895861.

- ^ a b Mitchell, D. R. (2007). "The evolution of eukaryotic cilia and flagella as motile and sensory organelles". Eukaryotic Membranes and Cytoskeleton. Adv Exp Med Biology. Vol. 607. pp. 130–40. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74021-8_11. ISBN 978-0-387-74020-1. PMC 3322410. PMID 17977465.

- ^ Zhang, Qing; Hu, Jinghua; Ling, Kun (2013-09-10). "Molecular views of Arf-like small GTPases in cilia and ciliopathies". Experimental Cell Research. Special Issue: Small GTPases. 319 (15): 2316–2322. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.03.024. ISSN 0014-4827. PMC 3742637. PMID 23548655.

- ^ Haycraft, Courtney J.; Serra, Rosa (2008-01-01), "Chapter 11 Cilia Involvement in Patterning and Maintenance of the Skeleton", Current Topics in Developmental Biology, Ciliary Function in Mammalian Development, 85, Academic Press: 303–332, doi:10.1016/s0070-2153(08)00811-9, ISBN 978-0-12-374453-1, PMC 3107512, PMID 19147010

- ^ Satir, P.; Christensen, Søren T. (June 2008). "Structure and function of mammalian cilia". Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 129 (6): 687–693. doi:10.1007/s00418-008-0416-9. PMC 2386530. PMID 18365235. 1432-119X.

- ^ "41.8: Excretion Systems - Flame Cells of Planaria and Nephridia of Worms". Biology LibreTexts. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ Björn, Lars Olof; Govindjee (2009). "The evolution of photosynthesis and chloroplasts". Current Science. 96 (11 June 10, 2009): 1466–1474. JSTOR 24104775.

- ^ Sato, N. (2006). "Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids". In Wise, R. R.; Hoober, J. K. (eds.). The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol. 23. Springer. pp. 75–102. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4061-0_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3.

- ^ a b Lew, Kristi; Fitzpatrick, Brad (2021). Plant Cells (Third ed.). Infobase Holdings, Inc. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-1-64693-728-8.

- ^ Etxeberria, Ed; et al. (July 2012). "In and out of the plant storage vacuole". Plant Science. 190: 52–61. Bibcode:2012PlnSc.190...52E. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.03.010. PMID 22608519.

- ^ Yoon, Hwan Su; Hackett, Jeremiah D.; Ciniglia, Claudia; Pinto, Gabriele; Bhattacharya, Debashish (May 2004). "A Molecular Timeline for the Origin of Photosynthetic Eukaryotes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (5): 809–818. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh075. ISSN 1537-1719. PMID 14963099.

- ^ Abka-Khajouei R, Tounsi L, Shahabi N, Patel AK, Abdelkafi S, Michaud P (May 2022). "Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates". Mar Drugs. 20 (6): 364. doi:10.3390/md20060364. PMC 9225620. PMID 35736167.

- ^ Steinberg G (March 2007). "Hyphal growth: a tale of motors, lipids, and the Spitzenkörper". Eukaryotic Cell. 6 (3): 351–60. doi:10.1128/EC.00381-06. PMC 1828937. PMID 17259546.

- ^ a b "8.16E: Cell Structure, Metabolism, and Motility". Biology LibreTexts. 23 June 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2025.

- ^ a b Vega, Leslie; White, Bret (2019). Fundamentals of Genetics. Ed-tech Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-83947-450-7.

- ^ Campbell Biology – Concepts and Connections. Pearson Education. 2009. p. 138.

- ^ Snustad, D. Peter; Simmons, Michael J. (2015). "DNA repair mechanisms". Principles of Genetics (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 333–336. ISBN 978-1-119-14228-7.

- ^ Smolin, Lori A.; Grosvenor, Mary B. (2019). Nutrition: Science and Applications (4 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-119-49527-7.

- ^ Alberts, B.; et al. (2002). "Chloroplasts and Photosynthesis". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. Retrieved 2025-10-04.

- ^ a b Ananthakrishnan, R.; Ehrlicher, A. (June 2007). "The forces behind cell movement". International Journal of Biological Sciences. 3 (5). Biolsci.org: 303–317. doi:10.7150/ijbs.3.303. PMC 1893118. PMID 17589565.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). Garland Science. pp. 973–975. ISBN 0-8153-4072-9.

- ^ Willingham, Emily. "Cells Solve an English Hedge Maze with the Same Skills They Use to Traverse the Body". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "How cells can find their way through the human body". phys.org. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Tweedy, Luke; Thomason, Peter A.; Paschke, Peggy I.; Martin, Kirsty; Machesky, Laura M.; Zagnoni, Michele; Insall, Robert H. (August 2020). "Seeing around corners: Cells solve mazes and respond at a distance using attractant breakdown". Science. 369 (6507) eaay9792. doi:10.1126/science.aay9792. PMID 32855311. S2CID 221342551. Archived from the original on 2020-09-12. Retrieved 2020-09-13.

- ^ D'Arcy, Mark S. (June 2019). "Cell death: a review of the major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy". Cell Biology International. 43 (6): 582–592. doi:10.1002/cbin.11137. PMID 30958602.

- ^ Yuan, J.; Ofengeim, D. (2024). "A guide to cell death pathways". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 25 (5): 379–395. doi:10.1038/s41580-023-00689-6. PMID 38110635.

- ^ a b Bernstein, C.; et al. (2000). "Cell Immortality: Maintenance of Cell Division Potential". Cell Immortalization. Progress in Molecular and Subcellular Biology. Vol. 24. pp. 23–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-06227-2_2. ISBN 978-3-642-08491-1. PMID 10547857.

- ^ Avise, J. C. (October 1993). "Perspective: The evolutionary biology of aging, sexual reproduction, and DNA repair". Evolution. 47 (5): 1293–1301. Bibcode:1993Evolu..47.1293A. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb02155.x. PMID 28564887.

- ^ Becker, Wayne M.; et al. (2009). The world of the cell. Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-321-55418-5.

- ^ Pátková, Irena; et al. (2012). "Developmental plasticity of bacterial colonies and consortia in germ-free and gnotobiotic settings". BMC Microbiology. 12 178. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-178. PMC 3583141. PMID 22894147.

- ^ Niklas, Karl J.; Newman, Stuart A. (January 2013). "The origins of multicellular organisms". Evolution & Development. 15 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1111/ede.12013. PMID 23331916.

- ^ Zeng, Hongkui (2022). "What is a cell type and how to define it?". Cell. 185 (15): 2739–2755. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.031. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 9342916. PMID 35868277.

- ^ Aruni, A. Wilson; Ramadass, P. (2019). Animal Tissue Culture. MJP Publisher. pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-81-8094-056-9.

- ^ Deasy, Bridget M. (2009). "Asymmetric Behavior in Stem Cells". In Rajasekhar, V. K.; Vemuri, M. C. (eds.). Regulatory Networks in Stem Cells. Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine. Humana Press. pp. 13–22. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-227-8_2. ISBN 978-1-60327-227-8.

- ^ Nair, Arathi; et al. (July 4, 2019). "Conceptual Evolution of Cell Signaling". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (13): 3292. doi:10.3390/ijms20133292. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 6651758. PMID 31277491.

- ^ a b Alberts, Bruce; et al. (2002). "General Principles of Cell Communication". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science.

- ^ Infante, Deliana (December 2, 2024). "How Dysregulated Cell Signaling Causes Disease". News-Medical.Net. Retrieved 2025-10-05.

- ^ a b c Grosberg, R. K.; Strathmann, R. R. (2007). "The evolution of multicellularity: A minor major transition?" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 38: 621–654. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.114735. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ^ Popper, Zoë A.; Michel, Gurvan; Hervé, Cécile; et al. (2011). "Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: from algae to flowering plants" (PDF). Annual Review of Plant Biology. 62 (1): 567–590. Bibcode:2011AnRPB..62..567P. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103809. hdl:10379/6762. PMID 21351878. S2CID 11961888. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-07-29. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ^ Bonner, John Tyler (1998). "The Origins of Multicellularity" (PDF). Integrative Biology. 1 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6602(1998)1:1<27::AID-INBI4>3.0.CO;2-6. ISSN 1093-4391. Archived from the original (PDF, 0.2 MB) on March 8, 2012.

- ^ Niklas, Karl J. (January 2014). "The evolutionary-developmental origins of multicellularity". American Journal of Botany. 101 (1): 6–25. Bibcode:2014AmJB..101....6N. doi:10.3732/ajb.1300314. PMID 24363320.

- ^ Albani, Abderrazak El; Bengtson, Stefan; Canfield, Donald E.; et al. (July 2010). "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature. 466 (7302): 100–104. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..100A. doi:10.1038/nature09166. PMID 20596019. S2CID 4331375.

- ^ Orgel, L. E. (December 1998). "The origin of life--a review of facts and speculations". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 23 (12): 491–495. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01300-0. PMID 9868373.

- ^ Chatterjee, S. (2023). "The RNA World: Reality or Dogma?". From Stardust to First Cells. Springer, Cham. pp. 97–107. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-23397-5_10. ISBN 978-3-031-23397-5.

- ^ Dodd, Matthew S.; Papineau, Dominic; Grenne, Tor; et al. (1 March 2017). "Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates". Nature. 543 (7643): 60–64. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...60D. doi:10.1038/nature21377. PMID 28252057. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ Betts, Holly C.; Puttick, Mark N.; Clark, James W.; Williams, Tom A.; Donoghue, Philip C. J.; Pisani, Davide (20 August 2018). "Integrated genomic and fossil evidence illuminates life's early evolution and eukaryote origin". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (10): 1556–1562. Bibcode:2018NatEE...2.1556B. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0644-x. PMC 6152910. PMID 30127539.

- ^ Griffiths, G. (December 2007). "Cell evolution and the problem of membrane topology". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 8 (12): 1018–1024. doi:10.1038/nrm2287. PMID 17971839. S2CID 31072778.

- ^ "First cells may have emerged because building blocks of proteins stabilized membranes". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ a b c d Latorre, A.; Durban, A; Moya, A.; Pereto, J. (2011). "The role of symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution". In Gargaud, Muriel; López-Garcìa, Purificacion; Martin, H. (eds.). Origins and Evolution of Life: An astrobiological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 326–339. ISBN 978-0-521-76131-4. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ a b Weiss, Madeline C.; Sousa, F. L.; Mrnjavac, N.; et al. (2016). "The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor" (PDF). Nature Microbiology. 1 (9): 16116. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.116. PMID 27562259. S2CID 2997255.

- ^ a b Strassert, Jürgen F. H.; Irisarri, Iker; Williams, Tom A.; Burki, Fabien (25 March 2021). "A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 1879. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.1879S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. PMC 7994803. PMID 33767194.

- ^ McGrath, Casey (31 May 2022). "Highlight: Unraveling the Origins of LUCA and LECA on the Tree of Life". Genome Biology and Evolution. 14 (6) evac072. doi:10.1093/gbe/evac072. PMC 9168435.

- ^ Leander, B. S. (May 2020). "Predatory protists". Current Biology. 30 (10): R510 – R516. Bibcode:2020CBio...30.R510L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.052. PMID 32428491. S2CID 218710816.

- ^ Gabaldón, T. (October 2021). "Origin and Early Evolution of the Eukaryotic Cell". Annual Review of Microbiology. 75 (1): 631–647. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062213. PMID 34343017. S2CID 236916203.

- ^ Woese, C.R.; Kandler, Otto; Wheelis, Mark L. (June 1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–4579. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ Hooke, Robert (1665). "Observation 18". Micrographia.

- ^ Maton, Anthea (1997). Cells Building Blocks of Life. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 44-45 The Cell Theory. ISBN 978-0-13-423476-2.

- ^ a b Gest, H. (2004). "The discovery of microorganisms by Robert Hooke and Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, fellows of the Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 58 (2): 187–201. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2004.0055. PMID 15209075. S2CID 8297229.

- ^ "History of the Cell: Discovering the Cell". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2025-08-01.

- ^ "The Origins Of The Word 'Cell'". National Public Radio. September 17, 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-08-05. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

- ^ "cellŭla". A Latin Dictionary. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. 1879. ISBN 978-1-9998557-8-9. Archived from the original on 2021-08-07. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^ Hooke, Robert (1665). Micrographia: ... London: Royal Society of London. p. 113.

... I could exceedingly plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey-comb, but that the pores of it were not regular [...] these pores, or cells, [...] were indeed the first microscopical pores I ever saw, and perhaps, that were ever seen, for I had not met with any Writer or Person, that had made any mention of them before this ...

– Hooke describing his observations on a thin slice of cork. See also: Robert Hooke Archived 1997-06-06 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Schwann, Theodor (1839). Mikroskopische Untersuchungen über die Uebereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachsthum der Thiere und Pflanzen. Berlin: Sander.

- ^ "4.3: Studying Cells - Cell Theory". Biology LibreTexts. 2018-07-05. Retrieved 2025-08-01.

- ^ Ribatti, Domenico (2018-03-01). "An historical note on the cell theory". Experimental Cell Research. 364 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.01.038. ISSN 0014-4827. PMID 29391153.

- ^ Ernst Ruska (January 1980). The Early Development of Electron Lenses and Electron Microscopy. Applied Optics. Vol. 25. Translated by T. Mulvey. p. 820. Bibcode:1986ApOpt..25..820R. doi:10.1364/AO.25.000820. ISBN 978-3-7776-0364-3.

- ^ Cornish-Bowden, Athel (7 December 2017). "Lynn Margulis and the origin of the eukaryotes". Journal of Theoretical Biology. The origin of mitosing cells: 50th anniversary of a classic paper by Lynn Sagan (Margulis). 434: 1. Bibcode:2017JThBi.434....1C. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.09.027. PMID 28992902.

External links

[edit]- "The Inner Life of the Cell". XVIVO website. – 2006 animation of molecular mechanisms inside cells

Cell (biology)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Key Characteristics

In biology, a cell is defined as the smallest structural and functional unit of life capable of independent reproduction and metabolism.[4] All living organisms are composed of one or more cells, which serve as the fundamental building blocks for tissues, organs, and entire multicellular bodies.[1] Cells exhibit several universal key characteristics that distinguish them as the basis of life: compartmentalization through a plasma membrane that separates the internal environment from the external one, enabling controlled exchanges; metabolism, involving enzymatic chemical reactions to process nutrients and generate energy, often stored as ATP; growth and responsiveness to environmental stimuli via receptors and signaling pathways; reproduction through cell division, ensuring propagation; and heredity encoded by DNA, which directs cellular structure, function, and inheritance.[6] These properties allow cells to maintain homeostasis, adapt to changes, and sustain life processes autonomously or in coordination within multicellular organisms.[5] Cells manifest in diverse forms, including unicellular organisms that exist as single, self-sufficient entities, such as bacteria (prokaryotes) and amoebae (eukaryotic protists), which perform all life functions independently.[7][8] In multicellular organisms like humans or plants, specialized cells collaborate, with examples including neurons for signal transmission or leaf cells for photosynthesis, yet each retains the core ability to divide and differentiate when needed.[1] Notably, viruses are distinguished from cells as non-cellular entities; they lack metabolism, independent reproduction, and cellular structures, instead relying on host cells to replicate their genetic material.[9] Cell sizes vary significantly by type, providing insight into their complexity and function. Prokaryotic cells, such as bacteria, typically range from 0.1 to 5 μm in diameter, reflecting their simpler organization. Eukaryotic cells, found in animals, plants, and fungi, are generally larger, measuring 10 to 100 μm, which accommodates membrane-bound organelles and greater internal compartmentalization. These scale differences underscore the evolutionary divergence between cell types while highlighting the cell's role as life's minimal viable unit.[5]Cell Theory

Cell theory, a cornerstone of modern biology, was formulated in the 19th century through the pioneering work of several key scientists. In 1838, German botanist Matthias Jakob Schleiden observed under the microscope that all plant tissues are aggregates of individual cells, proposing that the cell is the fundamental unit of plant structure and development; this insight was published in his seminal paper "Beiträge zur Phytogenesis" (Contributions to Phytogenesis).[10] Building on Schleiden's findings, German physiologist Theodor Schwann extended the concept to animals in 1839, demonstrating through detailed microscopic examinations that animal tissues similarly consist of cells and exhibit comparable growth patterns to plants; his comprehensive treatise, "Mikroskopische Untersuchungen über die Übereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachstum der Tiere und Pflanzen" (Microscopical Researches into the Accordance in the Structure and Growth of Animals and Plants), laid the groundwork for the theory's initial principles.[11] These contributions by Schleiden and Schwann established the unifying idea that cells form the basic building blocks of all living organisms.[12] The theory was completed in 1855 by German pathologist Rudolf Virchow, who, through his studies of tissue pathology and cell division, asserted that all cells originate from pre-existing cells—a principle encapsulated in his famous axiom "omnis cellula e cellula" (every cell from a cell); this was articulated in his lectures and subsequent publication "Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre" (Cellular Pathology as Based Upon Physiological and Pathological Histology).[13] Virchow's addition refuted earlier notions of spontaneous generation and emphasized cellular continuity in health and disease. The resulting classical cell theory comprises three core tenets: all living organisms are composed of one or more cells; the cell is the basic unit of structure, function, and organization in organisms; and all cells arise from pre-existing cells via division. Cell theory profoundly impacts biology by providing a unified framework that connects the structure and function of life across scales, from unicellular microbes to complex multicellular organisms; it underpins disciplines such as cytology, which examines cellular structures and processes, and microbiology, which investigates cellular life at the microscopic level.[15] In the modern era, the theory has been extended to incorporate advances in genetics and biochemistry: cells carry hereditary information through DNA, which is replicated and transmitted during division; moreover, cells serve as the primary sites for metabolic activities, including energy flow via processes like cellular respiration and information processing through molecular signaling.[16] Apparent exceptions, such as syncytia—multinucleated cytoplasmic masses in structures like skeletal muscle or certain fungi—do not contradict the theory, as they form through fusion of individual cells and function as single, albeit complex, cellular units with coordinated nuclear activity.[17]History of Cell Research

Early Discoveries

The invention of the compound microscope in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, building on earlier simple lenses, enabled the first glimpses into the microscopic world, though initial instruments suffered from poor magnification and image distortion. In 1665, English scientist Robert Hooke published Micrographia, detailing his observations of thin slices of cork viewed through a microscope with up to 50x magnification; he described the honeycomb-like compartments as "cells," likening them to small rooms, and noted their porous structure composed of rigid walls. These were actually the empty lignified cell walls of dead plant tissue from cork oak (Quercus suber), marking the first documented use of the term "cell" in biology.[18][19] Concurrently in the 1660s, Italian physician Marcello Malpighi employed early microscopes to examine plant and animal tissues, revealing intricate structures such as the vascular bundles in plants and the capillary networks connecting arteries and veins in frog lungs, which he described in works like De pulmonibus (1661). His studies of insect anatomy, including the tubular structures now known as Malpighian tubules, demonstrated that tissues in both plants and animals consisted of organized, minute components, laying groundwork for comparative histology. A decade later, in the 1670s, Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek crafted superior single-lens microscopes achieving 270x magnification and over 1 μm resolution; in letters to the Royal Society, he reported observing "animalcules"—tiny, motile organisms—in samples of pond water, rainwater, and dental plaque, which included protozoa like Paramecium and the first sightings of bacteria such as those in the mouth. These findings, published in Philosophical Transactions starting in 1677, expanded the known diversity of life and confirmed the ubiquity of microscopic entities.[20] Early microscopy's limitations, including chromatic and spherical aberrations that blurred images and restricted resolution to about 1-2 μm, fueled debates on cellular continuity; observers like 18th-century microscopists often misinterpreted tissue as a continuous fibrous network rather than discrete units, as finer details such as cell boundaries in living animal tissues remained elusive. In 1831, Scottish botanist Robert Brown advanced these observations by identifying a dark, opaque structure—the nucleus—within the cells of orchid (Orchidaceae) epidermal tissue during studies of fertilization, naming it in a presentation to the Linnean Society and emphasizing its consistent presence across plant cells. This discovery, detailed in his 1833 publication, highlighted internal cellular organization previously overlooked.[21][22] Building on these advances, the 1830s saw the formulation of cell theory. In 1838, German botanist Matthias Jakob Schleiden proposed that all plant tissues are composed of cells and that cells are the fundamental units of plant life. The following year, Theodor Schwann extended this idea to animals, stating that all living organisms are made up of cells. In 1855, Rudolf Virchow added the crucial insight that all cells arise from preexisting cells, completing the classical cell theory. These principles unified the understanding of life at the cellular level.[23] The transition to the 19th century brought pivotal improvements, such as achromatic lenses developed by Joseph Jackson Lister in the 1830s, which corrected color fringing and spherical distortion to achieve resolutions below 1 μm, enabling clearer views of dynamic cellular processes and paving the way for detailed investigations of cell division and morphology.[24]Development of Modern Understanding