Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of regions of the United States

View on Wikipedia

This is a list of some of the ways regions are defined in the United States. Many regions are defined in law or regulations by the federal government; others by shared culture and history, and others by economic factors.

Interstate regions

[edit]Census Bureau-designated regions and divisions

[edit]

Since 1950, the United States Census Bureau defines four statistical regions, with nine divisions.[1][2] The Census Bureau region definition is "widely used [...] for data collection and analysis",[3] and is the most commonly used classification system.[4][5][6][7]

Puerto Rico and other US territories are not part of any census region or census division.[8]

Federal Reserve Banks

[edit]

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 divided the country into twelve districts with a central Federal Reserve Bank in each district. These twelve Federal Reserve Banks together form a major part of the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States. Missouri is the only U.S. state to have two Federal Reserve locations within its borders, but several other states are also divided between more than one district.

- Boston

- New York

- Philadelphia

- Cleveland

- Richmond

- Atlanta

- Chicago

- St. Louis

- Minneapolis

- Kansas City

- Dallas

- San Francisco

Time zones

[edit]

- UTC−12:00 (Baker Island, Howland Island)

- Samoa Time Zone (American Samoa, Jarvis Island, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll, Palmyra Atoll)

- Hawaii–Aleutian Time Zone (Hawaii, Aleutian Islands (Alaska), Johnston Atoll)

- Alaska Time Zone (Alaska, excluding Aleutian Islands)

- Pacific Time Zone

- Arizona Time Zone (excluding the Navajo Nation)[9]

- Mountain Time Zone (excluding most parts of Arizona)

- Central Time Zone

- Eastern Time Zone

- Atlantic Time Zone (Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands)

- Chamorro Time Zone (Guam, Northern Mariana Islands)

- Wake Island Time Zone (Wake Island)

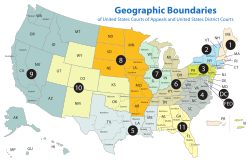

Courts of Appeals circuits

[edit]

- First Circuit

- Second Circuit

- Third Circuit

- Fourth Circuit

- Fifth Circuit

- Sixth Circuit

- Seventh Circuit

- Eighth Circuit

- Ninth Circuit

- Tenth Circuit

- Eleventh Circuit

- D.C. Circuit

The Federal Circuit is not a regional circuit. Its jurisdiction is nationwide but based on the subject matter.

Agency administrative regions

[edit]In 1969, the Office of Management and Budget published a list of ten "Standard Federal Regions",[10] to which federal agencies could be restructured as a means of standardizing government administration nationwide. Despite a finding in 1977 that this restructuring did not reduce administrative costs as initially expected,[11] and the complete rescinding of the standard region system in 1995,[12] several agencies continue to follow the system, including the Environmental Protection Agency[13] and the Department of Housing and Urban Development.[14]

Regions and office locations

[edit]

Region I

[edit]Office location: Boston

States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont

Region II

[edit]Office location: New York City

States: New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands

Region III

[edit]Office location: Philadelphia

States: Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia

Region IV

[edit]Office location: Atlanta

States: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee

Region V

[edit]Office location: Chicago

States: Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin

Region VI

[edit]Office location: Dallas

States: Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas

Region VII

[edit]Office location: Kansas City

States: Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska

Region VIII

[edit]Office location: Denver

States: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming

Region IX

[edit]Office location: San Francisco

States: Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa

Region X

[edit]Office location: Seattle

States: Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington

Bureau of Economic Analysis regions

[edit]

The Bureau of Economic Analysis defines regions for comparison of economic data.[15]

- New England: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont

- Mideast: Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C.

- Great Lakes: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin

- Plains: Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota

- Southeast: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia

- Southwest: Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas

- Rocky Mountain: Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming

- Far West: Alaska, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington

Unofficial regions

[edit]Multi-state regions

[edit]- American Frontier

- Appalachia

- Ark-La-Tex

- Auto Alley

- Backcountry

- Black Dirt Region

- Border states:

- The Californias

- Calumet Region

- The Carolinas

- Cascadia

- Central United States

- Coastal states

- Colorado Plateau

- Columbia Basin

- Contiguous United States

- The Dakotas

- Deep South

- Deseret

- Delmarva Peninsula

- Dixie

- Dixie Alley

- Driftless Area

- East Coast

- Eastern United States

- Flyover country

- Four Corners

- Great American Desert

- Great Appalachian Valley

- Great Basin

- Great Lakes Region

- Great Plains

- Gulf Coast

- Heartland

- High Plains

- Interior Plains

- Intermountain States

- Kentuckiana

- Llano Estacado

- Lower 48

- Michiana

- Mid-Atlantic states

- Middle America

- Mid-South states

- Midwestern United States

- Mississippi Delta

- Mojave Desert

- Mormon Corridor

- New England

- Nickajack

- North Woods

- Northeastern United States

- Northern United States

- Northwestern United States

- Ohio Valley

- Old South

- Old Southwest

- Ozarks

- Pacific Northwest

- Palouse

- Piedmont

- Piney Woods

- Rocky Mountains

- Siouxland

- Southeastern United States

- Southern United States

- Southwestern United States

- Tidewater

- Tornado Alley

- Trans-Appalachia

- Trans-Mississippi

- Twin Tiers

- Upland South

- Upper Midwest

- Virginias

- Waxhaws

- West Coast

- Western United States

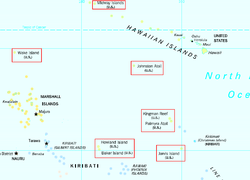

Multi-territory regions

[edit]- Mariana Islands (Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands)

- Samoan Islands (American Samoa, except Swains Island)[note 1]

- Virgin Islands (the Spanish Virgin Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands)[note 2]

The Belts

[edit]Interstate megalopolises

[edit]Interstate metropolitan areas

[edit]- Central Savannah River Area (part of Georgia and South Carolina)

- Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area (Washington, D.C. and parts of Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania)

- Washington metropolitan area (District of Columbia and parts of Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia)

- Greater Boston (parts of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire)

- Charlotte metropolitan area (parts of North Carolina and South Carolina)

- Chattanooga Metropolitan Area

- Chicago metropolitan area (parts of Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin)

- Cincinnati metropolitan area (parts of Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky)

- Columbus-Auburn-Opelika (GA-AL) Combined Statistical Area (parts of Georgia and Alabama)

- Delaware Valley (parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland)

- Evansville, IN–KY Metropolitan Statistical Area (parts of Indiana and Kentucky)

- Fargo–Moorhead (parts of North Dakota and Minnesota)

- Fort Smith metropolitan area (parts of Arkansas and Oklahoma)

- Front Range Urban Corridor (parts of Colorado and Wyoming)

- Greater Grand Forks (part of Minnesota and North Dakota)

- Hartford-Springfield (parts of Connecticut and Massachusetts)

- Kansas City metropolitan area (parts of Missouri and Kansas)

- Louisville metropolitan area (Kentuckiana) (parts of Kentucky and Indiana)

- Memphis metropolitan area (parts of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi)

- Michiana (parts of Michigan and Indiana)

- Minneapolis–Saint Paul (the Twin Cities) (parts of Minnesota and Wisconsin)

- New York metropolitan area (parts of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania)

- Omaha–Council Bluffs metropolitan area (parts of Nebraska and Iowa)

- Portland metropolitan area (parts of Oregon and Washington)

- Quad Cities (parts of Iowa and Illinois)

- Greater St. Louis (parts of Missouri and Illinois)

- Texarkana metropolitan area (parts of Texas and Arkansas)

- Tri-Cities (parts of Tennessee and Virginia)

- Twin Ports (Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin)

- Hampton Roads region (parts of Virginia and North Carolina)

- Youngstown–Warren–Boardman metropolitan statistical area (parts of Ohio and Pennsylvania)

Intrastate and intraterritory regions

[edit]Alabama

[edit]

Regions of Alabama include:

- Alabama Gulf Coast

- Canebrake

- Greater Birmingham

- Black Belt

- Central Alabama

- Lower Alabama

- Mobile Bay

- North Alabama

- Northeast Alabama

- Northwest Alabama

- South Alabama

Alaska

[edit]

Regions of Alaska include:

- Alaska Interior

- Alaska North Slope

- Alaska Panhandle

- Aleutian Islands

- Arctic Alaska

- Gold Belt

- The Bush

- Kenai Peninsula

- Matanuska-Susitna Valley

- Seward Peninsula

- Southcentral Alaska

- Southwest Alaska

- Tanana Valley

- Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta

American Samoa

[edit]

Regions of American Samoa include:

Arizona

[edit]

Regions of Arizona include:

- Arizona Strip

- Dinetah

- Grand Canyon

- North Central Arizona

- Northeast Arizona

- Northern Arizona

- Phoenix metropolitan area

- Southern Arizona

Arkansas

[edit]

Regions of Arkansas include:

- Arkansas Delta

- Arkansas River Valley

- Arkansas Timberlands

- Central Arkansas

- Crowley's Ridge

- Northwest Arkansas

- South Arkansas

California

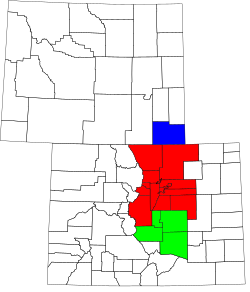

[edit]Colorado

[edit]

Regions of Colorado include:

- Central Colorado (part of Southern Rocky Mountains)

- Colorado Eastern Plains (part of High Plains)

- Colorado Mineral Belt (part of Southern Rocky Mountains)

- Colorado Piedmont (parts of the Front Range Urban Corridor and Colorado High Plains)

- Colorado Plateau (multi-state region)

- Colorado Western Slope (parts of Southern Rocky Mountains and Colorado Plateau)

- Denver Metropolitan Area (part of Front Range Urban Corridor)

- Four Corners Region (multi-state region of Colorado Plateau)

- Front Range Urban Corridor (multi-state region)

- High Plains (multi-state region of Great Plains)

- Mesa Verde

- North Central Colorado Urban Area (part of Front Range Urban Corridor)

- Northwestern Colorado (part of Southern Rocky Mountains)

- San Luis Valley

- South-Central Colorado

- South Central Colorado Urban Area (part of Front Range Urban Corridor)

- Southern Rocky Mountains (multi-state region of Rocky Mountains)

- Southwestern Colorado (parts of Southern Rocky Mountains and Colorado Plateau)

Connecticut

[edit]

Connecticut has nine official planning regions, which operate as councils of governments and are recognized as county equivalents by the U.S. Census Bureau. The nine regions are:

- Capitol Region

- Greater Bridgeport

- Lower Connecticut River Valley

- Naugatuck Valley

- Northeastern Connecticut

- Northwest Hills

- South Central Connecticut

- Southeastern Connecticut

- Western Connecticut

Some of Connecticut's informal regions include:

- Coastal Connecticut

- Connecticut panhandle/Gold Coast

- Farmington Valley

- Housatonic Valley

- Litchfield Hills

- Quiet Corner

Delaware

[edit]

Regions of Delaware include:

- "Upstate" or "Up North":

- Delaware Valley, also known as "Above the Canal" (referring to the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal)

"Slower Lower":

- Cape Region

- Central Kent

- Delaware coast

District of Columbia

[edit]Florida

[edit]

Directional regions of Florida include:

- Central Florida

- East Florida

- North Central Florida

- North Florida

- Northwest Florida

- Northeast Florida

- South Florida

- Southwest Florida

- West Florida

Local vernacular regions of Florida include:

- Big Bend

- Emerald Coast

- First Coast

- Florida Heartland

- Florida Keys

- Florida Panhandle

- Forgotten Coast

- Glades

- Gold Coast

- Halifax area (also Surf Coast and Fun Coast)

- Red Hills

- Nature Coast

- Space Coast

- Suncoast

- Tampa Bay Area

- Treasure Coast

Georgia

[edit]Regions of Georgia include:

- Atlanta metropolitan area

- Central Georgia

- Central Savannah River Area

- Colonial Coast

- Gold Belt

- Golden Isles of Georgia

- North Georgia

- North Georgia mountains (Northeast Georgia)

- Southern Rivers

- Southeast Georgia

- Wiregrass Region

Physiographic regions

[edit]Physiographic regions of Georgia include:

Guam

[edit]Regions of Guam include:

Hawaii

[edit]

Regions of Hawaii include:

- Hawaiʻi Island (Big Island)

- Kahoʻolawe

- Kauaʻi

- Kaʻula

- Lānaʻi

- Maui

- Molokaʻi

- Niʻihau

- Northwestern Hawaiian Islands[note 4]

- Oʻahu

Idaho

[edit]Regions of Idaho include:

- Central Idaho

- Eastern Idaho

- Idaho Panhandle

- Magic Valley

- North Central Idaho

- Palouse Hills

- Southern Idaho

- Southwestern Idaho

- Treasure Valley

Illinois

[edit]Regions of Illinois include:

- Central Illinois

- Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area

- Chicago metropolitan area

- Driftless Area

- Forgottonia

- Metro-East

- Metro Lakeland

- Military Tract of 1812

- Northern Illinois

- Northwestern Illinois

- Peoria, Illinois metropolitan area

- Quad Cities

- Rock River Valley

- Shawnee Hills

- Southern Illinois (sometimes, Little Egypt)

- Tri-State Area

- Wabash Valley

Indiana

[edit]

Regions of Indiana include:

- East Central Indiana

- Indianapolis metropolitan area

- Michiana

- Northern Indiana

- Northwest Indiana

- Southern Indiana

- Southwestern Indiana

- Wabash Valley

Iowa

[edit]

Regions of Iowa include:

- Coteau des Prairies

- Des Moines metropolitan area

- Dissected Till Plains

- Driftless Area

- Great River Road

- Honey Lands

- Iowa Great Lakes

- Loess Hills

- Omaha–Council Bluffs metropolitan area

- Quad Cities

- Siouxland

Kansas

[edit]Regions of Kansas include:

- East-Central Kansas

- Flint Hills

- High Plains

- Kansas City Metropolitan Area

- Missouri Rhineland

- North Central Kansas

- Osage Plains

- Ozarks

- Red Hills

- Santa Fe Trail

- Smoky Hills

- Southeast Kansas

Kentucky

[edit]Regions of Kentucky include:

- Bluegrass

- Cumberland Plateau or Eastern Coal Field

- Golden Triangle

- Jackson Purchase

- Pennyroyal Plateau

- Western Coal Field

Louisiana

[edit]

Regions of Louisiana include:

- Central Louisiana (Cen-La)

- Florida Parishes

- "French Louisiana" (Acadiana and Greater New Orleans)

- Greater New Orleans

- North Louisiana

- Southwest Louisiana

Maine

[edit]Regions of Maine include:

- Acadia

- Down East

- High Peaks / Maine Highlands

- Hundred-Mile Wilderness

- Kennebec Valley

- Maine Highlands

- Maine Lake Country

- Maine North Woods

- Mid Coast

- Penobscot Bay

- Southern Maine Coast

- Western Maine Mountains

Maryland

[edit]

Regions of Maryland include:

- Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area

- Capital region

- Chesapeake Bay

- Eastern Shore of Maryland

- Patapsco Valley

- Southern Maryland

- Western Maryland

Regions of Maryland shared with other states include:

- Allegheny Mountains

- Atlantic coastal plain

- Blue Ridge Mountains

- Cumberland Valley

- Delaware Valley

- Delmarva Peninsula consists of Maryland's and Virginia's Eastern Shore and all of Delaware

- Piedmont (United States)

- Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians

Massachusetts

[edit]

Regions of Massachusetts include:

- Central Massachusetts

- Northeastern Massachusetts

- Southeastern Massachusetts

- Western Massachusetts

- The Berkshires (shown in map)

- Housatonic Valley

- Pioneer Valley

- Quabbin-Swift River Valley

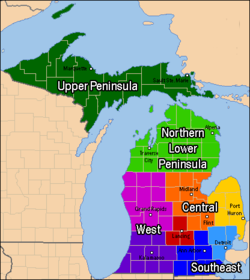

Michigan

[edit]

Regions of Michigan include:

Lower Peninsula

[edit]Upper Peninsula

[edit]Minnesota

[edit]

Regions of Minnesota include:

- Arrowhead Region

- Boundary Waters

- Buffalo Ridge

- Central Minnesota

- Coulee Region

- Iron Range

- Minnesota River Valley

- North Shore

- Northwest Angle

- Pipestone Region

- Red River Valley

- Southeast Minnesota

- Twin Cities Metro

Mississippi

[edit]Regions of Mississippi include:

Missouri

[edit]

Regions of Missouri include:

- Boonslick

- Bootheel

- Dissected Till Plains

- Kansas City Metropolitan Area

- Lead Belt

- Little Dixie

- Ozarks

- Platte Purchase

- St. Louis Metropolitan Area

Montana

[edit]Regions of Montana include:

- Big Horn Mountains

- Eastern Montana

- Glacier Country

- Glacier National Park

- Regional designations of Montana

- The Flathead

- Two Medicine

- Western Montana

- Yellowstone National Park

Nebraska

[edit]

Regions of Nebraska include:

Nevada

[edit]Regions of Nevada include:

New Hampshire

[edit]Regions of New Hampshire include:

- Connecticut River Valley

- Dartmouth-Lake Sunapee Region (overlaps with Connecticut River Valley)

- Great North Woods Region

- Lakes Region

- Merrimack Valley

- Monadnock Region (overlaps with Connecticut River Valley)

- Seacoast Region

- White Mountains

New Jersey

[edit]Regions of New Jersey include:

New Mexico

[edit]Regions of New Mexico include:

New York

[edit]

The ten regions of New York, as defined by the Empire State Development Corporation:

- Capital District – counties : Albany, Columbia, Greene, Warren, Washington, Saratoga, Schenectady, Rensselaer

- Central New York – counties: Cortland, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oswego, Madison

- Finger Lakes – counties: Orleans, Genesee, Wyoming, Monroe, Livingston, Wayne, Ontario, Yates, Seneca

- Hudson Valley – counties: Sullivan, Ulster, Dutchess, Orange, Putnam, Rockland, Westchester

- Long Island – counties: Nassau, Suffolk

- Mohawk Valley – counties: Oneida, Herkimer, Fulton, Montgomery, Otsego, Schoharie

- New York City – counties (boroughs): New York (Manhattan), Bronx (The Bronx), Queens (Queens), Kings (Brooklyn), Richmond (Staten Island)

- North Country – counties : St. Lawrence, Lewis, Jefferson, Hamilton, Essex, Clinton, Franklin

- Southern Tier – counties: Steuben, Schuyler, Chemung, Tompkins, Tioga, Chenango, Broome, Delaware

- Western New York – counties: Niagara, Erie, Chautauqua, Cattaraugus, Allegany

Regions of New York state include:

- Downstate New York

- Upstate New York

North Carolina

[edit]

Regions of North Carolina include:

- Eastern North Carolina

- Central North Carolina

- Western North Carolina

North Dakota

[edit]Regions of North Dakota include:

- Badlands

- Drift Prairie

- Missouri Escarpment

- Missouri Plateau (Missouri Coteau in French)

- Red River Valley

Northern Mariana Islands

[edit]

Regions of the Northern Mariana Islands include:

Ohio

[edit]

Regions of Ohio include:

- Allegheny Plateau

- Appalachian Ohio

- Cincinnati-Northern Kentucky metropolitan area

- Columbus, Ohio metropolitan area

- Connecticut Western Reserve (historic)

- Firelands

- Great Black Swamp (shared with Indiana)

- Knobs

- Lake Erie Islands

- Miami Valley

- Northeast Ohio (often used interchangeably with Greater Cleveland, but also includes the counties of Ashtabula, Portage, Summit, Trumbull, Mahoning and Columbiana.)

- Northwest Ohio

- Pennyroyal

Oklahoma

[edit]

Regions of Oklahoma include:

- Central Oklahoma

- Cherokee Outlet

- Green Country

- Choctaw Country

- Little Dixie

- Northwestern Oklahoma

- Panhandle

- South Central Oklahoma

- Southwestern Oklahoma

Oregon

[edit]

Regions of Oregon include:

- Cascade Range

- Central Oregon

- Columbia Plateau

- Columbia River

- Columbia River Gorge

- Eastern Oregon

- Goose Lake Valley

- Harney Basin

- High Desert

- Hood River Valley

- Mount Hood Corridor

- Northwest Oregon

- Oregon Coast

- Palouse

- Portland metropolitan area

- Rogue Valley

- Southern Oregon

- Treasure Valley

- Tualatin Valley

- Warner Valley

- Western Oregon

- Willamette Valley

Pennsylvania

[edit]Regions of Pennsylvania include:

- Allegheny National Forest

- Coal Region

- Cumberland Valley

- Delaware River Valley

- Dutch Country

- Endless Mountains

- Highlands Region

- Laurel Highlands

- Lehigh Valley

- Lenapehoking

- Northern Tier

- Northeastern Pennsylvania

- Philadelphia metropolitan area

- Philadelphia Main Line

- Pittsburgh metropolitan area

- Slate Belt

- South Central Pennsylvania

- Susquehanna Valley

- The Poconos

- Western Pennsylvania

- Wyoming Valley

Puerto Rico

[edit]

Regions of Puerto Rico include:

Rhode Island

[edit]Regions of Rhode Island include:

South Carolina

[edit]Regions of South Carolina include:

- The Lowcountry

- The Midlands

- The Upstate

- Travel/Tourism locations

- Other geographical distinctions:

South Dakota

[edit]

Regions of South Dakota include:

- Badlands

- Black Hills

- Coteau des Prairies

- East River and West River, divided by the Missouri River

Tennessee

[edit]The Grand Divisions of Tennessee include:

- East Tennessee

- Middle Tennessee

- West Tennessee

- Other geographical distinctions:

Texas

[edit]

Regions of Texas include:

- Apacheria

- Brazos Valley

- Central Texas

- Comancheria

- Gulf Coast

- East Texas

- North Texas

- South Texas

- Southeast Texas

- Texas Midwest/West-Central Texas (includes Abilene, San Angelo, Brownwood, Texas)

- Texas Urban Triangle (Houston to San Antonio to Dallas-Fort Worth)

- West Texas

- Concho Valley

- Edwards Plateau

- Llano Estacado (a portion of northwest Texas)

- Permian Basin

- South Plains (includes 24 counties south of the Texas Panhandle and north of the Permian Basin)

- Texas Panhandle (pictured)

- Trans-Pecos

- Great Plains

U.S. Minor Outlying Islands

[edit]

Regions of United States Minor Outlying Islands include:

- Baker Island

- Howland Island

- Jarvis Island

- Johnston Island

- Kingman Reef

- Midway Atoll

- Navassa Island[note 5]

- Palmyra Atoll

- Wake Island[note 6]

U.S. Virgin Islands

[edit]Regions of United States Virgin Islands include:

Utah

[edit]Regions of Utah include:

- Cache Valley

- Colorado Plateau

- Dixie

- Great Salt Lake Desert

- Mojave Desert

- San Rafael Swell

- Uinta Mountains

- Wasatch Back

- Wasatch Front

- Wasatch Range

Vermont

[edit]Regions of Vermont include:

Virginia

[edit]

Regions of Virginia include:

- Eastern Shore

- Greater Richmond Region

- Hampton Roads

- Historic Triangle

- Northern Neck

- Northern Virginia

- Piedmont region of Virginia

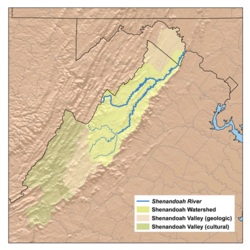

- Shenandoah Valley

- South Hampton Roads

- Southside Virginia

- Southwest Virginia

- Tidewater

- Tri-Cities

- Tsenacommacah

- Virginia Peninsula

Washington

[edit]Regions of Washington include:

- Central Washington

- Columbia Plateau

- Eastern Washington

- Kitsap Peninsula

- Long Beach Peninsula

- Okanogan Country

- Olympic Mountains

- Olympic Peninsula

- Puget Sound

- San Juan Islands

- Skagit Valley

- Southwest Washington

- Tri-Cities

- Walla Walla Valley

- Western Washington

- Yakima Valley

West Virginia

[edit]Regions of West Virginia include:

- Eastern Panhandle

- North Central West Virginia

- Northern Panhandle

- Potomac Highlands

- Southern West Virginia

Wisconsin

[edit]

Wisconsin is divided into five geographic regions:

Wyoming

[edit]Regions of Wyoming include:

See also

[edit]- Geography of the United States

- Historic regions of the United States

- List of metropolitan areas of the United States

- Media market, e.g., Nielsen Designated Market Area

- Political divisions of the United States

- Regional stock exchanges of the United States

- United States territory

- Vernacular geography

- U.S. Caribbean region

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ This region also includes the Independent State of Samoa, which is not a part of the United States

- ^ This region also includes the British Virgin Islands, which is not a part of the United States

- ^ Claimed by Tokelau[16]

- ^ Midway Atoll, part of the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, is not politically part of Hawaii; it is one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands

- ^ Claimed by Haiti

- ^ Claimed by the Marshall Islands

References

[edit]- ^ "Statistical Groupings of States and Counties" (PDF). census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ United States Census Bureau, Geography Division. "Census Regions and Divisions of the United States" (PDF). Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ "The National Energy Modeling System: An Overview 2003" (Report #: DOE/EIA-0581, October 2009). United States Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration.

- ^ "The most widely used regional definitions and follow those of the U.S. Bureau of the Census." Seymour Sudman and Norman M. Bradburn, Asking Questions: A Practical Guide to Questionnaire Design (1982). Jossey-Bass: p. 205.

- ^ "Perhaps the most widely used regional classification system is one developed by the U.S. Census Bureau." Dale M. Lewison, Retailing, Prentice Hall (1997): p. 384. ISBN 978-0-13-461427-4

- ^ "[M]ost demographic and food consumption data are presented in this four-region format." Pamela Goyan Kittler, Kathryn P. Sucher, Food and Culture, Cengage Learning (2008): p.475. ISBN 9780495115410

- ^ "Census Bureau Regions and Divisions with State FIPS Codes" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "Geographic Terms and Concepts - Census Divisions and Census Regions". US Census Bureau. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "No DST in Most of Arizona". www.timeanddate.com. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Standard Federal Regions, Office of Management and Budget, 1969, Circular A-105

- ^ Office of Management and Budget (August 17, 1977), Standardized Federal Regions: Little Effect on Agency Management of Personnel, Government Accountability Office, FPCD-77-39

- ^ 60 FR 15171

- ^ Williams, Dennis C. (March 1993), Why Are Our Regional Offices and Labs Located Where They Are? A Historical Perspective on Siting, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- ^ HUD's Regions, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, September 20, 2017

- ^ "BEA Regions". Bureau of Economic Analysis. February 18, 2004. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook - American Samoa. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

External links

[edit]List of regions of the United States

View on GrokipediaOfficial Interstate Regions

U.S. Census Bureau Regions and Divisions

The U.S. Census Bureau delineates the United States into four main regions—Northeast, Midwest, South, and West—and further subdivides these into nine divisions for the purpose of organizing and presenting statistical data from censuses and surveys.[1] This framework, with the nine divisions originating in the 1910 Census population report (excluding Alaska and Hawaii, added later), provides a consistent geographic basis for aggregating data on population, economy, and demographics.[5] The four broader regions emerged as groupings of these divisions in the mid-20th century to facilitate national-level analysis, remaining stable without structural alterations following the 2020 Census, which primarily refined urban-rural classifications and sub-county boundaries rather than regional delineations.[6] These regions and divisions serve as standard geographic units for federal statistical reporting, enabling comparisons across states with similar historical, geographic, or economic traits while supporting policy formulation, resource allocation, and congressional apportionment computations that rely on state-level data aggregated regionally.[7] The Census Bureau established this system to address the need for summary units beyond states and counties, ensuring data comparability over time since the divisions' inception over a century ago.[3] No substantive changes to the regional or divisional composition occurred post-2020, preserving the framework for ongoing decennial and economic censuses.[8] The following table outlines the four regions, their constituent divisions, and assigned states or equivalents:| Region | Division | States/Territories |

|---|---|---|

| Northeast | New England | Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont[2] |

| Northeast | Middle Atlantic | New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania[2] |

| Midwest | East North Central | Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin[3] |

| Midwest | West North Central | Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota[3] |

| South | South Atlantic | Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia[3] |

| South | East South Central | Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee[3] |

| South | West South Central | Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas[3] |

| West | Mountain | Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming[3] |

| West | Pacific | Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington[3] |

Federal Reserve Bank Districts

The Federal Reserve System divides the contiguous United States, along with certain territories, into 12 districts to decentralize central banking functions, as provided under the Federal Reserve Act signed into law on December 23, 1913.[9] These districts were outlined in 1914 by the Reserve Bank Organization Committee, which selected boundaries based on contemporaneous patterns of trade, industry, and financial flows to ensure effective regional representation and responsiveness to economic conditions, deliberately crossing state lines where necessary to capture integrated commercial areas.[10] [11] The delineations prioritize practical economic oversight over political subdivisions, with district lines drawn at the county level, leading to splits in seven states; no major revisions have occurred since, though U.S. territories like Puerto Rico were later assigned to District 2, and Alaska and Hawaii to District 12 upon statehood.[12] Each Federal Reserve Bank operates independently within its district under oversight from the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., implementing open market operations to influence national monetary policy, supervising depository institutions for compliance and safety, providing liquidity through discount window lending, processing payments and settlements, and producing data-driven analyses of local economic indicators—such as employment, manufacturing, and agriculture—to inform Federal Open Market Committee deliberations.[13] [14] [15] This structure fosters input from diverse regional perspectives, mitigating risks of centralized bias in policy formulation.[16] The districts, numbered 1 through 12 with headquarters in designated cities, encompass the following primary areas (noting county-level exceptions for split states like Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Missouri, and New Mexico):| District | Headquarters | Primary Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boston, Massachusetts | Connecticut (excluding Fairfield County), Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont |

| 2 | New York, New York | New York; northern New Jersey (12 counties); Fairfield County, Connecticut; Puerto Rico; U.S. Virgin Islands |

| 3 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Delaware; southern New Jersey; Pennsylvania |

| 4 | Cleveland, Ohio | Most of Kentucky; most of Ohio; 44 western Pennsylvania counties; 19 northern West Virginia counties |

| 5 | Richmond, Virginia | District of Columbia; most of Maryland; North Carolina; South Carolina; Virginia; 50 southern West Virginia counties |

| 6 | Atlanta, Georgia | Alabama; Florida; Georgia; most of Louisiana; most of Mississippi; Tennessee |

| 7 | Chicago, Illinois | Illinois; Indiana; Iowa; Michigan; Wisconsin |

| 8 | St. Louis, Missouri | Arkansas; southern half of Illinois and Indiana; most of Kentucky; northern Mississippi; entire Missouri; western Tennessee |

| 9 | Minneapolis, Minnesota | Upper Peninsula of Michigan; Minnesota; Montana; North Dakota; South Dakota; northwestern Wisconsin |

| 10 | Kansas City, Missouri | Colorado; Kansas; western Missouri; Nebraska; Oklahoma; Wyoming |

| 11 | Dallas, Texas | Northern Louisiana; most of New Mexico; Texas (excluding El Paso County) |

| 12 | San Francisco, California | Alaska; Arizona; California; Guam; Hawaii; Idaho; Nevada; Oregon; Utah; Washington; American Samoa; Northern Mariana Islands[17][18] |

Standard Time Zones

The standard time zones of the United States were codified in the Standard Time Act of 1918, which divided the nation into five zones—Eastern, Central, Mountain, Pacific, and Alaska—to synchronize railroad operations and facilitate interstate commerce by aligning local solar time with practical economic needs rather than rigid 15-degree longitude meridians.[19] [20] Zone boundaries, defined by the Interstate Commerce Commission and later the Department of Transportation, incorporate adjustments for state lines, metropolitan areas, and transportation corridors to minimize disruptions in trade and daily coordination.[21] The Uniform Time Act of 1966 amended these provisions to mandate uniform daylight saving time (DST) observance—advancing clocks one hour from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November—across observing areas, while permitting states or territories to opt out via legislation approved by the Secretary of Transportation.[21] [22] The Energy Policy Act of 2005 further extended the DST period by approximately one month, shifting the start to the second Sunday in March and the end to the first Sunday in November, effective from 2007, to promote energy conservation through extended evening daylight for commerce.[23] These zones span multiple states or territories, reflecting causal alignments with approximate 15-degree longitude bands (roughly one hour apart) centered on meridians 75°W for Eastern, 90°W for Central, 105°W for Mountain, and 120°W for Pacific, though irregular boundaries prioritize functional unity over solar precision. Most states observe DST, but exemptions apply: Hawaii remains on Hawaii Standard Time year-round due to its equatorial latitude minimizing seasonal light variation, and Arizona (excluding the Navajo Nation) forgoes DST to maintain consistent agricultural and construction schedules in its arid climate.[21] [24]| Time Zone | UTC Offset (Standard/DST) | States/Territories Primarily Covered |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern | -5 / -4 | Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia (plus eastern portions of Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan)[25] |

| Central | -6 / -5 | Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Wisconsin (plus western portions of Florida panhandle, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Tennessee, Texas)[25] |

| Mountain | -7 / -6 | Arizona, Colorado, Idaho (southern), Montana, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming (plus western portions of Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Texas)[25] |

| Pacific | -8 / -7 | California, Nevada (most), Oregon, Washington (plus northern Idaho)[25] |

| Alaska | -9 / -8 | Most of Alaska (excluding Aleutian Islands west of 169°30'W)[25] |

| Hawaii-Aleutian | -10 / -10 (Hawaii; -9/-8 Aleutians) | Hawaii; Aleutian Islands (Alaska, observing DST)[25] |

U.S. Courts of Appeals Circuits

The United States Courts of Appeals exercise appellate jurisdiction over decisions from the 94 federal district courts, organized into 13 circuits as defined by federal statute. These circuits, established primarily by the Judiciary Act of 1891, divide the country into regional groups of states and territories to manage caseloads efficiently, prioritizing judicial administration over perfect geographic cohesion—for instance, the Ninth Circuit spans a vast Pacific expanse including Alaska and Hawaii. Boundaries are codified in 28 U.S.C. § 41 and have remained largely unchanged since the division of the former Fifth Circuit into the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits, effective October 1, 1981, to address growing dockets in the Southeast. The structure supports federalism by decentralizing appellate review while ensuring uniformity under Supreme Court oversight, with circuits reflecting 19th-century expansions and post-Civil War reorganizations rather than modern demographic shifts.[26][27][28] Twelve of the circuits cover geographic regions, while the thirteenth, the Federal Circuit, has nationwide subject-matter jurisdiction over specialized cases such as patents, international trade, and claims against the United States, without territorial boundaries tied to states. Each regional circuit includes multiple district courts, with judges appointed for life under Article III of the Constitution to insulate rulings from political pressures. Caseloads vary significantly; for example, the Ninth Circuit handles over 12,000 appeals annually due to its population density, compared to fewer than 1,500 in the First Circuit.[29][28] The following table enumerates the regional circuits and their constituent states and territories:| Circuit | States and Territories |

|---|---|

| First | Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Puerto Rico[26] |

| Second | Connecticut, New York, Vermont[26] |

| Third | Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virgin Islands[26] |

| Fourth | Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia[26] |

| Fifth | Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas[26] |

| Sixth | Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, Tennessee[26] |

| Seventh | Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin[26] |

| Eighth | Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota[26] |

| Ninth | Alaska, Arizona, California, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Northern Mariana Islands, Oregon, Washington[26] |

| Tenth | Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah, Wyoming[26] |

| Eleventh | Alabama, Florida, Georgia[26] |

| District of Columbia | District of Columbia[26] |

Bureau of Economic Analysis Regions

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), a principal agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce, delineates eight economic regions encompassing all states and the District of Columbia to aggregate and analyze subnational economic indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP), personal income by major source, compensation of employees, and full- and part-time employment. These regions enable comparisons of economic growth, productivity, and industry contributions across areas with shared market characteristics, supporting policy analysis and forecasting grounded in empirical data on production, earnings, and interregional trade. Established following the 1950 Census, the groupings reflect cross-sectional similarities in socioeconomic profiles, including income levels, employment patterns, and commodity production, rather than arbitrary geographic boundaries.[30][31][32] BEA regions differ from Census Bureau divisions by emphasizing economic interdependencies—such as supply chain linkages and labor market flows—over demographic or cultural homogenizations, allowing for more precise tracking of real economic activity decoupled from political subdivisions. For instance, regional GDP estimates, released quarterly, capture value added by industry (e.g., manufacturing in the Great Lakes versus services in the Far West), with chained 2017 dollars used to adjust for inflation and reveal underlying productivity trends. Personal income data, comprising wages, proprietor income, and transfer receipts, further highlight disparities, such as the Mideast region's concentration of finance and professional services contributing over 20% of national totals in recent years. These metrics remained structurally consistent post-2020 Census revisions, as BEA prioritizes continuity in time-series comparability for longitudinal analysis.[33] The regions and their constituent states are as follows:| Region | States and District |

|---|---|

| New England | Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont |

| Mideast | Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania |

| Great Lakes | Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin |

| Plains | Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota |

| Southeast | Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia |

| Southwest | Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas |

| Rocky Mountain | Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming |

| Far West | Alaska, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Washington |

Other Federal Agency Administrative Regions

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) divides the United States into ten administrative regions to facilitate the enforcement of environmental laws, pollution control, and resource management, with boundaries designed for logistical efficiency rather than strict alignment with state lines or Census divisions. Region 1, based in Boston, encompasses Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Region 2, in New York City, includes New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; Region 3, in Philadelphia, covers Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia; Region 4, in Atlanta, serves Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee; Region 5, in Chicago, handles Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin; Region 6, in Dallas, oversees Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas; Region 7, in Lenexa, Kansas, includes Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska; Region 8, in Denver, manages Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming; Region 9, in San Francisco, addresses Arizona, California, Guam, Hawaii, Nevada, and American Samoa; and Region 10, in Seattle, covers Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.[34] These regions enable coordinated responses to issues like air quality and hazardous waste, though their groupings sometimes aggregate states with divergent industrial profiles, such as pairing energy-dependent Texas with agricultural Oklahoma in Region 6. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) employs a similar ten-region framework for administering health programs, grants, and policy implementation, with adjustments to prioritize public health delivery over geographic uniformity. HHS Region 1 mirrors EPA's New England coverage (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont); Region 2 includes New Jersey and New York; Region 3 covers Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia; Region 4 serves Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; Region 5 handles Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin; Region 6 encompasses Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas; Region 7 includes Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska; Region 8 manages Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming; Region 9 addresses Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Guam, American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau; and Region 10 covers Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.[35] Established under the 1953 Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (reorganized as HHS in 1980), these divisions support targeted interventions in areas like Medicare oversight and disease surveillance, but critics note they can impose uniform federal standards that underemphasize regional variations in healthcare access and demographics, such as urban density in Region 2 versus rural expanses in Region 7.[35] The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), under the Department of Homeland Security, structures its operations across ten regions optimized for rapid disaster response, recovery coordination, and preparedness training, drawing on a model refined since its 1979 consolidation. FEMA Region 1 aligns with New England states (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont); Region 2 includes New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; Region 3 covers Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia; Region 4 serves Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and the U.S. Virgin Islands (overlapping with HHS); Region 5 handles Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin; Region 6 encompasses Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas; Region 7 includes Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and the tribal nations within; Region 8 manages Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Wyoming, and tribal areas; Region 9 addresses Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Guam, American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of Palau; and Region 10 covers Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and tribal lands.[36] This setup, updated minimally in the 2020s for enhanced logistics amid events like Hurricane Helene in 2024, prioritizes hazard-prone clusters—evident in Region 4's focus on southeastern storm corridors—but has drawn scrutiny for occasionally sidelining state-specific risks, such as California's wildfires versus Idaho's floods, in favor of centralized command.[36]Geographic and Physiographic Regions

Major Physiographic Provinces and Divisions

The physiographic divisions of the contiguous United States, as classified by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), consist of eight major divisions based on Nevin M. Fenneman's 1946 framework, which emphasizes geological structure, landform evolution through erosion and tectonics, and rock composition observed via field mapping and topographic analysis. These divisions aggregate 25 provinces and 86 sections, prioritizing causal factors like uplift, sedimentation, and glacial action over political lines, enabling predictions of soil fertility, mineral deposits, and hydrology from elevation gradients and stratigraphic data. For instance, average elevations range from near sea level in coastal plains to over 10,000 feet in mountain systems, correlating with seismic stability and resource types such as sedimentary basins for oil or crystalline shields for iron ore.[37][38] The Laurentian Upland represents the southern extension of the Precambrian Canadian Shield, featuring resistant igneous and metamorphic rocks eroded to low rolling hills and exposed bedrock, with elevations typically under 1,500 feet shaped by multiple Pleistocene glaciations that deposited till and created lakes. It spans northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan's Upper Peninsula, where thin, acidic soils from glacial scour limit agriculture but support mining of ancient ore bodies.[39] The Atlantic Plain comprises unconsolidated Quaternary sediments overlying older coastal deposits, forming flat to gently sloping lowlands with minimal relief, often below 500 feet, dissected by rivers and fringed by barrier islands due to subsidence and sea-level fluctuations. This division extends along the eastern seaboard from New York to Florida, encompassing Delaware, Maryland, and parts of the Carolinas, where sandy aquifers and peat soils facilitate groundwater storage but heighten vulnerability to storm surges.[39] The Appalachian Highlands encompass folded and faulted Paleozoic sedimentary rocks uplifted during the Alleghenian orogeny, resulting in parallel ridges, valleys, and dissected plateaus with elevations reaching 6,684 feet at Mount Mitchell, eroded over 200 million years into a mature landscape of quartzite caps and shale slopes. It covers areas from New York through Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Virginia, and into Tennessee and Georgia, influencing linear drainage patterns and coal-rich strata from Carboniferous swamps.[39] The Interior Plains, including the Great Plains and Central Lowland, feature thick sequences of Phanerozoic sedimentary rocks gently dipping westward, with flat to undulating surfaces at 500–5,000 feet elevation, shaped by fluvial aggradation and eolian deposition rather than recent tectonics. This expansive division underlies states from the Dakotas southward to Texas and eastward to Ohio and Illinois, where chernozem soils from loess cover support extensive grasslands and fossil aquifers like the Ogallala Formation.[39] The Interior Highlands consist of uplifted Paleozoic plateaus and mountains, including the Ozark and Ouachita systems, with elevations up to 2,753 feet at Magazine Mountain, characterized by karst topography, stream dissection, and resistant sandstone ridges from Ouachita folding. Confined to Missouri, Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma, these features stem from the same orogenic events as the Appalachians but preserved by less erosion, yielding cherty soils and lead-zinc deposits.[39] The Rocky Mountain System arises from Laramide orogeny-driven uplift of Precambrian cores overlain by younger sediments, producing high, asymmetric ranges with peaks exceeding 14,000 feet, such as Mount Elbert at 14,440 feet, flanked by fault-block margins and alpine glaciers. It traverses Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico, where thin atmospheric pressure at altitude correlates with sparse vegetation and metallic mineral veins from igneous intrusions.[39] The Intermontane Basins, or Basin and Range Province, exhibit extensional tectonics fragmenting the crust into horst-and-graben structures since the Miocene, with alternating narrow ranges and broad basins at 4,000–6,000 feet average elevation, internally drained by playas and arroyos. Predominant in Nevada, Utah, and parts of Idaho, California, and Oregon, this division's north-south trending faults drive seismic activity and concentrate evaporite minerals in closed basins.[39] The Pacific Mountain System integrates subduction-related volcanism and strike-slip faulting, forming coastal ranges, the Sierra Nevada batholith, and Cascade volcanoes with elevations to 14,505 feet at Mount Whitney, featuring granitic intrusions, lava flows, and deep canyons from rapid uplift. It parallels the Pacific from Washington through Oregon and California, where plate convergence causes frequent earthquakes and fertile volcanic soils supporting coniferous forests.[39]Hydrologic and Climatic Regions

The United States is divided into 21 major hydrologic regions by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), using a hierarchical system of hydrologic unit codes (HUCs) that delineate drainage basins based on natural topographic divides and water flow patterns, with regions numbered from 01 (New England) to 21 (Texas Gulf). These units facilitate analysis of surface water resources, encompassing successively smaller subregions, basins, and watersheds down to 12-digit HUCs covering areas as small as 10,000 acres. The Mississippi River Basin, spanning HUC regions 05 (Upper Mississippi), 06 (Missouri), 07 (Lower Mississippi), 10 (Arkansas-White-Red), and parts of others, drains 41% of the contiguous U.S. with a total area of 1,150,000 square miles, channeling precipitation from the Rockies eastward to the Gulf of Mexico and influencing flood dynamics across the Midwest and South Central states.[40][41][42] In contrast, the Great Basin (HUC region 16) forms an endorheic system of interior drainage covering 200,000 square miles across Nevada, Utah, and adjacent states, where rivers like the Humboldt terminate in saline lakes such as the Great Salt Lake due to evaporation exceeding inflow, resulting in minimal surface outflow to oceans. The Colorado River Basin (HUC regions 11, 14, and 18) aggregates 246,000 square miles from the Rockies through the Southwest, sustaining arid ecosystems via snowmelt-driven flows averaging 15 million acre-feet annually at Lee's Ferry, Arizona, though allocations strain under variable monsoonal and winter precipitation. These basins highlight causal roles of topography in directing water: continental divides like the Rockies funnel moisture into exorheic systems eastward while isolating closed basins westward, amplifying regional water scarcity where evaporation rates exceed 2,000 mm yearly in lowlands.[43][44] Climatic regions, adapted from the Köppen-Geiger classification by agencies like NOAA, segment the U.S. into zones defined by temperature thresholds (e.g., coldest month above 0°C for temperate C/D groups) and precipitation regimes (e.g., dry months below 1/25 of annual total for arid B types), revealing patterns driven by latitude, elevation, and orographic effects. The Southeast features humid subtropical (Cfa) conditions with mean annual precipitation of 1,200–1,600 mm and summer highs exceeding 30°C, fostering dense vegetation but prone to hurricanes; the Midwest exhibits humid continental (Dfa/Dfb) climates with 600–1,200 mm precipitation, cold winters averaging -10°C in January, and hot summers up to 25°C July means, supporting agriculture via freeze-thaw cycles. The Pacific Northwest displays marine west coast (Cfb) traits with mild temperatures (January 5°C, July 18°C) and heavy winter rainfall over 1,000 mm from Pacific storms, while the Southwest's semi-arid (BSk/BWh) zones receive under 300 mm annually, with diurnal temperature swings amplified by low humidity.[45][46] Topography exerts deterministic influence on these variabilities: the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains intercept Pacific moisture, yielding orographic precipitation exceeding 2,000 mm on windward slopes (e.g., Washington Cascades) but casting rain shadows leeward, where Great Basin aridity stems from descending dry air with precipitation dropping below 250 mm, as subsidence warms adiabatically by 10°C per kilometer descent. This elevational barrier similarly desiccates the Great Plains eastward of the Rockies, contrasting with moister Atlantic-influenced zones, underscoring how uplift and barrier effects override latitudinal gradients in fostering distinct hydrologic-climatic provinces.[47][48]Natural Resource Belts

The Appalachian and Illinois Basin Coal Belts encompass a vast area from northern Pennsylvania southward through West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and into Alabama for the Appalachian portion, with the Illinois Basin extending across Illinois, western Kentucky, southwestern Indiana, and parts of western Pennsylvania and Tennessee. These regions hold significant bituminous and subbituminous coal reserves, shaped by ancient sedimentary basins. From 1972 to 2021, the Appalachian Basin produced 31% of total U.S. coal output, while the Illinois Basin accounted for 14%, reflecting their role in powering industrial and electric generation needs.[49][50] The Permian Basin Oil and Gas Belt, spanning 66 counties in western Texas and southeastern New Mexico, contains stacked hydrocarbon formations like the Wolfcamp and Bone Spring shales, enabling high-volume extraction via horizontal drilling and fracking. Between 2020 and 2024, ten Permian counties drove 93% of U.S. crude oil production growth, with output from Lea and Eddy Counties in New Mexico alone adding nearly 1 million barrels per day to national totals. In 2024, the Permian contributed over 6 million barrels per day of crude oil and condensate, bolstering U.S. energy independence through interior basin dominance.[51][52] The Mesabi-Marquette Iron Ore Belt includes the Mesabi Range in northeastern Minnesota and the Marquette Range in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, featuring Precambrian banded iron formations processed mainly as taconite pellets. U.S. iron ore production reached an estimated 44 million tons in 2023, with nearly all domestic output derived from these ranges via open-pit mining and beneficiation. This concentration supports steelmaking feedstock, with Minnesota operations alone yielding over 90% of the national total in recent years.[53][54] The Pacific Northwest Timber Belt, primarily Washington and Oregon's coastal and Cascade forests, dominates U.S. softwood production with Douglas fir, hemlock, and cedar stands on federal, state, and private lands. In recent assessments, these states lead national lumber output, with Oregon and Washington harvesting millions of board feet annually to supply construction and manufacturing, underscoring renewable resource extraction in temperate rainforest zones.[55] These belts highlight resource endowments in geologically favorable interior and western interiors, where extraction volumes exceed coastal contributions, enabling raw material self-reliance for national industry.[56]Cultural, Economic, and Unofficial Multi-State Regions

Historical and Cultural Regions

Historical and cultural regions of the United States arose from colonial settlement patterns, ethnic migrations, and economic adaptations that created enduring multi-state identities distinct from federal administrative divisions. Early English Puritans in the 1630s founded compact townships in New England, fostering a Yankee culture of self-reliance, literacy, and communal governance that spread westward via Yankee migrations into upstate New York and the Upper Midwest by the early 19th century.[57] In contrast, the South developed a Cavalier tradition among English gentry descendants, emphasizing hierarchical agrarian societies, personal honor, and resistance to centralized authority, as seen in Virginia's Tidewater plantations established after 1607.[58] These divergences, rooted in transatlantic cultural imports rather than later ideological constructs, were amplified by the frontier process described in Frederick Jackson Turner's 1893 thesis, which argued that successive westward settlements democratized institutions while adapting eastern norms to new environments, such as turning New England mercantilism into Midwest commercial farming.[59] The Midwest Heartland, encompassing states from Ohio to Minnesota, crystallized in the 19th century through waves of German, Scandinavian, and Irish immigrants who introduced Lutheran work ethics and smallholder agriculture, blending with Yankee influences to form a yeoman ethos of practicality and isolationism; by 1900, foreign-born residents comprised over 20% of the population in states like Wisconsin and Minnesota.[60] Further west, the Spanish Borderlands—stretching from Florida to California—bear legacies of 16th- to 18th-century Spanish missions and presidios, where Hispanic ranching economies and Catholic syncretism with indigenous practices persisted despite U.S. annexation after 1848, shaping bilingual enclaves in New Mexico and southern Texas with populations over 40% Hispanic by the early 20th century.[61] These regions' boundaries, often fluid and contested in popular narratives, reflect causal drivers like soil suitability and kinship networks more than media portrayals that oversimplify them into binary North-South conflicts, ignoring ethnic mosaics evident in 1880 census data showing clustered immigrant origins.[62] Post-Civil War industrialization carved the Rust Belt across Great Lakes states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois, where steel and auto manufacturing boomed from 1870 to 1950, employing millions in unionized factories before declining due to global competition and labor rigidities; manufacturing jobs fell 28% between 1950 and 1980 as firms relocated southward.[63] Concurrently, the Sun Belt emerged in the Southeast and Southwest through post-World War II migrations drawn by air-conditioned amenities, defense contracts, and lower taxes, with net inflows of 3 million from the Northeast and Midwest between 1950 and 1970, boosting populations in Florida, Texas, and Arizona by over 50% in some metro areas via causal factors like reduced transport costs and suburban sprawl.[64] These shifts, documented in Bureau of Labor Statistics data, underscore how economic dislocations propelled cultural realignments, with Rust Belt communities retaining blue-collar solidarity amid deindustrialization while Sun Belt arrivals diluted traditional agrarian ties in favor of service-oriented individualism.[65]Agricultural and Economic Belts

The agricultural belts of the United States are informal regions delineated by dominant crop and livestock production patterns, as tracked by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), reflecting adaptations to local soil fertility, precipitation levels, and temperature regimes that enable specialized, high-yield farming. These belts emerged from 19th- and 20th-century settlement patterns and technological advancements, such as hybrid seeds and mechanization, prioritizing cash crops suited to export markets and domestic feed demands over diversified subsistence. Unlike physiographic divisions based solely on geology and hydrology, agricultural belts emphasize economic outputs driven by farmer decisions, with USDA data showing concentrations where yields exceed national averages due to optimal environmental matches— for instance, the Corn Belt's loess soils and long growing seasons support over 90% of U.S. corn acreage in just a few states. Corn Belt: Encompassing core states like Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Nebraska, and Minnesota, this region produces the majority of U.S. corn for grain, with 2023 output reaching a record 15.3 billion bushels at an average yield of 177.3 bushels per acre, driven by intensive row cropping on flat, fertile plains. Iowa alone accounted for about 19% of national production, harvesting over 2.8 billion bushels, while Illinois contributed roughly 15%, underscoring the belt's role in supplying 30% of global corn exports for animal feed, ethanol, and food processing. These efficiencies stem from market-responsive practices, including precision agriculture and crop rotation with soybeans, which have sustained yields despite variable weather, contributing to U.S. agricultural trade surpluses exceeding $20 billion annually in grains.[66][67] Wheat Belt: Primarily in the Great Plains, including Kansas, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and parts of Montana and South Dakota, this belt divides into winter wheat areas (sown in fall for early harvest) and spring wheat zones, with 2023 U.S. production totaling about 1.9 billion bushels, led by Kansas at over 300 million bushels from hard red winter varieties suited to semi-arid conditions. Winter wheat dominates 70-80% of output, thriving on the region's wheatgrasses and minimal irrigation needs, enabling exports of milling-quality grain to over 30 countries; North Dakota's spring wheat yields averaged 48 bushels per acre in recent years, reflecting dryland farming adaptations that prioritize drought-resistant cultivars over irrigated alternatives elsewhere.[68][69] Cotton Belt: Spanning 17 southern states from Texas to the Carolinas, with peak production in Texas (over 5 million bales in 2024), Georgia, Mississippi, and Arkansas, this belt yielded 14.41 million bales of upland cotton in 2024, concentrated in the Delta and Southeast subregions where black clay soils and 200+ frost-free days support boll weevil-resistant varieties. Texas produced about 45% of the national total, leveraging mechanized harvesting and genetically modified seeds to achieve yields of 800-900 pounds per acre, bolstering U.S. exports that captured 40% of the global market share despite competition from synthetic fibers.[70][71] Dairy Belt: Centered in the Upper Midwest, particularly Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, this region specializes in milk production from Holstein herds grazing improved pastures, with Wisconsin ranking first nationally at over 31 billion pounds of milk in 2023, followed by Minnesota's 10.5 billion pounds, facilitated by cool climates and corn silage feeds from adjacent belts. These states account for about 25% of U.S. dairy output, emphasizing cooperative models and export-oriented cheese production, where farm-scale efficiencies—averaging 25,000 pounds per cow annually—outpace warmer regions requiring more supplemental feed.[72] The Cotton Belt overlaps geographically with the Bible Belt in southeastern states like Mississippi and Alabama, where agricultural economies intertwine with cultural patterns, sustaining rural communities through crop revenues exceeding $5 billion annually while highlighting adaptations to subtropical humidity via pest management and varietal selection. Overall, these belts underpin U.S. food security, generating over $100 billion in farm cash receipts from field crops and livestock in 2023, with productivity gains from private-sector innovations outstripping public subsidies in causal impact on output.Interstate Megalopolises and Metropolitan Statistical Areas

The Northeast Megalopolis, often termed BosWash, encompasses a continuous urban corridor from Boston, Massachusetts, to Washington, D.C., spanning approximately 500 miles and integrating multiple metropolitan areas across Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, with a combined population exceeding 50 million as of recent estimates driven by economic interdependence and infrastructure links like Interstate 95.[73] This region exemplifies agglomeration economies, where proximity fosters higher productivity, innovation, and GDP concentration, contributing over 20% of U.S. economic output through sectors like finance, technology, and government.[74] In the Southeast, the Piedmont Crescent, also known as the Piedmont Atlantic Megaregion, links urban centers from Richmond, Virginia, through the Carolinas to Atlanta, Georgia, and extending influences into Alabama and Tennessee, characterized by interconnected highways like I-85 and shared economic activities in manufacturing, logistics, and services, supporting a population of around 25 million.[74] The Texas Triangle forms another prominent interstate cluster, centered on Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin, covering over 70,000 square miles across Texas with a population surpassing 20 million as of 2021 data, bolstered by energy, aerospace, and tech industries that leverage intraregional trade and labor mobility along corridors like I-35.[75] These megalopolises highlight causal benefits of urban density, including specialized labor pools and knowledge spillovers, which empirical studies link to sustained per capita income growth exceeding national averages.[74] Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) provide the official federal framework for delineating interstate economic integration, defined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) as regions with at least one urban core of 50,000 or more residents, plus adjacent counties where at least 25% of the employed population commutes to the core, enabling cross-state boundaries when commuting data from the American Community Survey confirms ties.[76] OMB's July 2023 revisions, based on 2020 Census data, updated these delineations to reflect post-pandemic shifts while maintaining criteria for interstate components, resulting in 392 MSAs nationwide, of which dozens span states, such as the New York-Newark-Jersey City MSA across New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (population 19.6 million in 2020).[77][76] Prominent interstate MSAs underscore productivity hubs; for instance, the Chicago-Naperville-Elgin MSA integrates Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin with 9.4 million residents, driven by manufacturing and logistics commuting patterns, while the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria MSA covers the District of Columbia, Virginia, Maryland, and West Virginia, encompassing 6.4 million people focused on federal and professional services.[76] The Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington MSA spans Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, with 6.2 million inhabitants linked by pharmaceutical and education sectors.[78] These areas, updated in 2023 to incorporate new commuting thresholds without altering core interstate linkages, facilitate targeted federal resource allocation and reveal how cross-border economic ties enhance resilience and output, countering notions that deconcentration reduces efficiency.[77][79]| MSA Name | States Spanned | 2020 Population (millions) |

|---|---|---|

| New York-Newark-Jersey City | NY, NJ, PA | 19.6 |

| Chicago-Naperville-Elgin | IL, IN, WI | 9.4 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria | DC, VA, MD, WV | 6.4 |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington | PA, NJ, DE, MD | 6.2 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Newton | MA, NH | 4.9 |