Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Arkansas

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Mockingbird |

| Butterfly | Diana fritillary |

| Flower | Apple blossom |

| Insect | Western honeybee |

| Mammal | White-tailed deer |

| Tree | Pine tree |

| Vegetable | South Arkansas vine ripe pink tomato |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Milk |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Food | Pecan |

| Gemstone | Diamond |

| Mineral | Quartz |

| Rock | Bauxite |

| Soil | Stuttgart |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2003 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

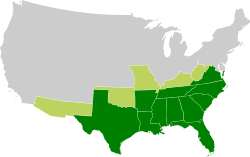

Arkansas (/ˈɑːrkənsɔː/ ⓘ AR-kən-saw[c]) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States.[11][12] It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma to the west. Its name derives from the Osage language, and refers to their relatives, the Quapaw people.[13] The state's diverse geography ranges from the mountainous regions of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains, which make up the U.S. Interior Highlands, to the densely forested land in the south known as the Arkansas Timberlands, to the eastern lowlands along the Mississippi River and the Arkansas Delta.

Previously part of French Louisiana and the Louisiana Purchase, the Territory of Arkansas was admitted to the Union as the 25th state on June 15, 1836.[14] Much of the Delta had been developed for cotton plantations, and landowners there largely depended on enslaved African Americans' labor. In 1861, Arkansas seceded from the United States and joined the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. On returning to the Union in 1868, Arkansas continued to suffer economically, due to its overreliance on the large-scale plantation economy. Cotton remained the leading commodity crop, and the cotton market declined. Because farmers and businessmen did not diversify and there was little industrial investment, the state fell behind in economic opportunity. In the late 19th century, the state instituted various Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise and segregate the African-American population. White interests dominated Arkansas's politics, with disenfranchisement of African Americans and refusal to reapportion the legislature; only after the federal legislation passed were more African Americans able to vote. During the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, Arkansas and particularly Little Rock were major battlegrounds for efforts to integrate schools. Following World War II in the 1940s, Arkansas began to diversify its economy and see prosperity. During the 1960s, the state became the base of the Walmart corporation, the world's largest company by revenue, headquartered in Bentonville.

Arkansas is the 29th largest by area and the 33rd most populous state, with a population of just over three million at the 2020 census.[15] The capital and most populous city is Little Rock, in the central part of the state, a hub for transportation, business, culture, and government. The northwestern corner of the state, namely the Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers Metropolitan Area, is a population, education, cultural, and economic center. The Fort Smith Metropolitan Area is also an economic center and is known for its historic sites related to western expansion and the persecution of Native Americans.[16] The largest city in the state's eastern part is Jonesboro. The largest city in the state's southeastern part is Pine Bluff.

In the 21st century, Arkansas's economy is based on service industries, aircraft, poultry, steel, and tourism, along with important commodity crops of cotton, soybeans and rice. The state supports a network of public universities and colleges, including two major university systems: Arkansas State University System and University of Arkansas System. Arkansas's culture is observable in museums, theaters, novels, television shows, restaurants, and athletic venues across the state.

Etymology

[edit]The name Arkansas initially applied to the Arkansas River. It derives from a French term, Arcansas, their plural term for their transliteration of akansa, an Algonquian term for the Quapaw people,[17] which is believed to translate to "south wind people".[18][19] These were a Dhegiha Siouan-speaking people who settled in Arkansas around the 13th century. Kansa is likely also the root term for Kansas, which was named after the related Kaw people.[17]

The name has been pronounced and spelled in a variety of ways.[c] In 1881, the state legislature defined the official pronunciation of Arkansas as having the final "s" be silent (as it would be in French). A dispute had arisen between the state's two senators over the pronunciation issue. One favored /ˈɑːrkənsɔː/ (AR-kən-saw), the other /ɑːrˈkænzəs/ (ar-KAN-zəs).[c]

In 2007, the state legislature passed a non-binding resolution declaring that the possessive form of the state's name is Arkansas's, which the state government has increasingly followed.[21][22]

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Early history

[edit]

Before European settlement of North America, Arkansas was inhabited by indigenous peoples for thousands of years. The Caddo, Osage, and Quapaw peoples encountered European explorers. The first of these Europeans was Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1541, who crossed the Mississippi and marched across central Arkansas and the Ozark Mountains. After finding nothing he considered of value and encountering native resistance the entire way, he and his men returned to the Mississippi River where de Soto fell ill. From his deathbed he ordered his men to massacre all the men of the nearby village of Anilco, who he feared had been plotting with a powerful polity down the Mississippi River, Quigualtam. His men obeyed and did not stop with the men, but were said to have massacred women and children as well. He died the following day in what is believed to be the vicinity of modern-day McArthur, Arkansas, in May 1542. His body was weighted down with sand and he was consigned to a watery grave in the Mississippi River under cover of darkness by his men. De Soto had attempted to deceive the native population into thinking he was an immortal deity, sun of the sun, in order to forestall attack by outraged Native Americans on his by then weakened and bedraggled army. In order to keep the ruse up, his men informed the locals that de Soto had ascended into the sky. His will at the time of his death listed "four Indian slaves, three horses and 700 hogs" which were auctioned off. The starving men, who had been living off maize stolen from natives, immediately started butchering the hogs and later, commanded by former aide-de-camp Moscoso, attempted an overland return to Mexico. They made it as far as Texas before running into territory too dry for maize farming and too thinly populated to sustain themselves by stealing food from the locals. The expedition promptly backtracked to Arkansas. After building a small fleet of boats they then headed down the Mississippi River and eventually on to Mexico by water.[23][24]

Later explorers included the French Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet in 1673, and Frenchmen Robert La Salle and Henri de Tonti in 1681.[25][26] Tonti established Arkansas Post at a Quapaw village in 1686, making it the first European settlement in the territory.[27] The early Spanish or French explorers of the state gave it its name, which is probably a phonetic spelling of the Illinois tribe's name for the Quapaw people, who lived downriver from them.[28][c] The name Arkansas has been pronounced and spelled in a variety of fashions. The region was organized as the Territory of Arkansaw on July 4, 1819, with the territory admitted to the United States as the state of Arkansas on June 15, 1836. The name was historically /ˈɑːrkənsɔː/, /ɑːrˈkænzəs/, and several other variants. Historically and modernly, the people of Arkansas call themselves either "Arkansans" or "Arkansawyers". In 1881, the Arkansas General Assembly passed Arkansas Code 1-4-105 (official text):

Whereas, confusion of practice has arisen in the pronunciation of the name of our state and it is deemed important that the true pronunciation should be determined for use in oral official proceedings.

And, whereas, the matter has been thoroughly investigated by the State Historical Society and the Eclectic Society of Little Rock, which have agreed upon the correct pronunciation as derived from history, and the early usage of the American immigrants.

Be it therefore resolved by both houses of the General Assembly, that the only true pronunciation of the name of the state, in the opinion of this body, is that received by the French from the native Indians and committed to writing in the French word representing the sound. It should be pronounced in three (3) syllables, with the final "s" silent, the "a" in each syllable with the Italian sound, and the accent on the first and last syllables. The pronunciation with the accent on the second syllable with the sound of "a" in "man" and the sounding of the terminal "s" is an innovation to be discouraged.

Citizens of the state of Kansas often pronounce the Arkansas River as /ɑːrˈkænzəs/, in a manner similar to the common pronunciation of the name of their state.

Settlers, such as fur trappers, moved to Arkansas in the early 18th century. These people used Arkansas Post as a home base and entrepôt.[27] During the colonial period, Arkansas changed hands between France and Spain following the Seven Years' War, although neither showed interest in the remote settlement of Arkansas Post.[29] In April 1783, Arkansas saw its only battle of the American Revolutionary War, a brief siege of the post by British Captain James Colbert with the assistance of the Choctaw and Chickasaw.[30]

Purchase and statehood

[edit]

Napoleon Bonaparte sold French Louisiana to the United States in 1803, including all of Arkansas, in a transaction known today as the Louisiana Purchase. French soldiers remained as a garrison at Arkansas Post. Following the purchase, the balanced give-and-take relationship between settlers and Native Americans began to change all along the frontier, including in Arkansas.[31] Following a controversy over allowing slavery in the territory, the Territory of Arkansas was organized on July 4, 1819.[c] Gradual emancipation in Arkansas was struck down by one vote, the Speaker of the House Henry Clay, allowing Arkansas to organize as a slave territory.[32]

Slavery became a wedge issue in Arkansas, forming a geographic divide that remained for decades. Owners and operators of the cotton plantation economy in southeast Arkansas firmly supported slavery, as they perceived slave labor as the best or "only" economically viable method of harvesting their commodity crops.[33] The "hill country" of northwest Arkansas was unable to grow cotton and relied on a cash-scarce, subsistence farming economy.[34]

As European Americans settled throughout the East Coast and into the Midwest, in the 1830s the United States government forced the removal of many Native American tribes to Arkansas and Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Additional Native American removals began in earnest during the territorial period, with final Quapaw removal complete by 1833 as they were pushed into Indian Territory.[36] The capital was relocated from Arkansas Post to Little Rock in 1821, during the territorial period.[37]

When Arkansas applied for statehood, the slavery issue was again raised in Washington, D.C. Congress eventually approved the Arkansas Constitution after a 25-hour session, admitting Arkansas on June 15, 1836, as the 25th state and the 13th slave state, having a population of about 60,000.[38] Arkansas struggled with taxation to support its new state government, a problem made worse by a state banking scandal and worse yet by the Panic of 1837.

Civil War and Reconstruction

[edit]

In early antebellum Arkansas, the southeast Arkansas slave-based economy developed rapidly. On the eve of the American Civil War in 1860, enslaved African Americans numbered 111,115 people, just over 25% of the state's population.[39] A plantation system based largely on cotton agriculture developed that, after the war, kept the state and region behind the nation for decades.[40] The wealth developed among planters of southeast Arkansas caused a political rift between the northwest and southeast.[41]

Many politicians were elected to office from the Family, the Southern rights political force in antebellum Arkansas. Residents generally wanted to avoid a civil war. When the Gulf states seceded in early 1861, delegates to a convention called to determine whether Arkansas should secede referred the question back to the voters for a referendum to be held in August.[41] Arkansas did not secede until Abraham Lincoln demanded Arkansas troops be sent to Fort Sumter to quell the rebellion there. On May 6, the members of the state convention, having been recalled by the convention president, voted to terminate Arkansas's membership in the Union and join the Confederate States of America.[41]

Arkansas held a very important position for the Rebels, maintaining control of the Mississippi River and surrounding Southern states. The bloody Battle of Wilson's Creek just across the border in Missouri shocked many Arkansans who thought the war would be a quick and decisive Southern victory. Battles early in the war took place in northwest Arkansas, including the Battle of Cane Hill, Battle of Pea Ridge, and Battle of Prairie Grove. Union general Samuel Curtis swept across the state to Helena in the Delta in 1862. Little Rock was captured the following year. The government shifted the state Confederate capital to Hot Springs, and then again to Washington from 1863 to 1865, for the remainder of the war. Throughout the state, guerrilla warfare ravaged the countryside and destroyed cities.[42] Passion for the Confederate cause waned after implementation of programs such as the draft, high taxes, and martial law.

Under the Military Reconstruction Act, Congress declared Arkansas restored to the Union in June 1868, after the Legislature accepted the 14th Amendment. The Republican-controlled reconstruction legislature established universal male suffrage (though temporarily disfranchising former Confederate Army officers, who were all Democrats), a public education system for blacks and whites, and passed general issues to improve the state and help more of the population. The State soon came under control of the Radical Republicans and Unionists, and led by Governor Powell Clayton, they presided over a time of great upheaval as Confederate sympathizers and the Ku Klux Klan fought the new developments, particularly voting rights for African Americans.

End of Reconstruction and late 19th century

[edit]In 1874, the Brooks-Baxter War, a political struggle between factions of the Republican Party shook Little Rock and the state governorship. It was settled only when President Ulysses S. Grant ordered Joseph Brooks to disperse his militant supporters.[43]

Following the Brooks-Baxter War, a new state constitution was ratified, re-enfranchising former Confederates and effectively bringing an end to Reconstruction.

In 1881, the Arkansas state legislature enacted a bill that adopted an official pronunciation of the state's name, to combat a controversy then simmering. (See Law and Government below.)

After Reconstruction, the state began to receive more immigrants and migrants. Chinese, Italian, and Syrian men were recruited for farm labor in the developing Delta region. None of these nationalities stayed long at farm labor; the Chinese especially, as they quickly became small merchants in towns around the Delta. Many Chinese became such successful merchants in small towns that they were able to educate their children at college.[44]

Construction of railroads enabled more farmers to get their products to market. It also brought new development into different parts of the state, including the Ozarks, where some areas were developed as resorts. In a few years at the end of the 19th century, for instance, Eureka Springs in Carroll County grew to 10,000 people, rapidly becoming a tourist destination and the fourth-largest city of the state. It featured newly constructed, elegant resort hotels and spas planned around its natural springs, considered to have healthful properties. The town's attractions included horse racing and other entertainment. It appealed to a wide variety of classes, becoming almost as popular as Hot Springs.

Rise of the Jim Crow laws and early 20th century

[edit]

In the late 1880s, the worsening agricultural depression catalyzed Populist and third party movements, leading to interracial coalitions. Struggling to stay in power, in the 1890s the Democrats in Arkansas followed other Southern states in passing legislation and constitutional amendments that disfranchised blacks and poor whites. In 1891 state legislators passed a requirement for a literacy test, knowing it would exclude many blacks and whites. At the time, more than 25% of the population could neither read nor write. In 1892, they amended the state constitution to require a poll tax and more complex residency requirements, both of which adversely affected poor people and sharecroppers, forcing most blacks and many poor whites from voter rolls.

By 1900 the Democratic Party expanded use of the white primary in county and state elections, further denying blacks a part in the political process. Only in the primary was there any competition among candidates, as Democrats held all the power. The state was a Democratic one-party state for decades, until after passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 to enforce constitutional rights.[45]

Between 1905 and 1911, Arkansas began to receive a small immigration of German, Slovak, and Scots-Irish from Europe. The German and Slovak peoples settled in the eastern part of the state known as the Prairie, and the Irish founded small communities in the southeast part of the state. The Germans were mostly Lutheran and the Slovaks were primarily Catholic. The Irish were mostly Protestant from Ulster, of Scots and Northern Borders descent. Some early 20th-century immigration included people from eastern Europe. Together, these immigrants made the Delta more diverse than the rest of the state. In the same years, some black migrants moved into the area because of opportunities to develop the bottomlands and own their own property.

Black sharecroppers began to try to organize a farmers' union after World War I. They were seeking better conditions of payment and accounting from white landowners of the area cotton plantations. Whites resisted any change and often tried to break up their meetings. On September 30, 1919, two white men, including a local deputy, tried to break up a meeting of black sharecroppers who were trying to organize a farmers' union. After a white deputy was killed in a confrontation with guards at the meeting, word spread to town and around the area.[citation needed] Hundreds of whites from Phillips and neighboring areas rushed to suppress the blacks, and started attacking blacks at large. Governor Charles Hillman Brough requested federal troops to stop what was called the Elaine massacre. White mobs spread throughout the county, killing an estimated 237 blacks before most of the violence was suppressed after October 1.[46] Five whites also died in the incident. The governor accompanied the troops to the scene; President Woodrow Wilson had approved their use.

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 flooded the areas along the Ouachita Rivers along with many other rivers.

Based on the order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt given shortly after the Empire of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, nearly 16,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from the West Coast of the United States and incarcerated in two internment camps in the Arkansas Delta.[47] The Rohwer Camp in Desha County operated from September 1942 to November 1945 and at its peak interned 8,475 prisoners.[47] The Jerome War Relocation Center in Drew County operated from October 1942 to June 1944 and held about 8,000.[47]

Fall of segregation

[edit]After the Supreme Court ruled segregation in public schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), some students worked to integrate schools in the state. The Little Rock Nine brought Arkansas to national attention in 1957 when the federal government had to intervene to protect African-American students trying to integrate a high school in the capital. Governor Orval Faubus had ordered the Arkansas National Guard to help segregationists prevent nine African-American students from enrolling at Little Rock's Central High School. After attempting three times to contact Faubus, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent 1,000 troops from the active-duty 101st Airborne Division to escort and protect the African-American students as they entered school on September 25, 1957. In defiance of federal court orders to integrate, the governor and city of Little Rock decided to close the high schools for the remainder of the school year. By the fall of 1959, the Little Rock high schools were completely integrated.[48]

Geography

[edit]

Boundaries

[edit]Arkansas borders Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, Oklahoma to the west, Missouri to the north, and Tennessee and Mississippi to the east. The United States Census Bureau classifies Arkansas as a southern state, sub-categorized among the West South Central States.[12] The Mississippi River forms most of its eastern border, except in Clay and Greene counties, where the St. Francis River forms the western boundary of the Missouri Bootheel, and in many places where the channel of the Mississippi has meandered (or been straightened by man) from its original 1836 course.[citation needed]

Terrain

[edit]

Arkansas can generally be split into two halves, the highlands in the northwest and the lowlands of the southeast.[49] The highlands are part of the Southern Interior Highlands, including The Ozarks and the Ouachita Mountains. The southern lowlands include the Gulf Coastal Plain and the Arkansas Delta.[50] This split can yield to a regional division into northwest, southwest, northeast, southeast, and central Arkansas. These regions are broad and not defined along county lines. Arkansas has seven distinct natural regions: the Ozark Mountains, Ouachita Mountains, Arkansas River Valley, Gulf Coastal Plain, Crowley's Ridge, and the Arkansas Delta, with Central Arkansas sometimes included as a blend of multiple regions.[51]

The southeastern part of Arkansas along the Mississippi Alluvial Plain is sometimes called the Arkansas Delta. This region is a flat landscape of rich alluvial soils formed by repeated flooding of the adjacent Mississippi. Farther from the river, in the southeastern part of the state, the Grand Prairie has a more undulating landscape. Both are fertile agricultural areas. The Delta region is bisected by a geological formation known as Crowley's Ridge. A narrow band of rolling hills, Crowley's Ridge rises 250 to 500 feet (76 to 152 m) above the surrounding alluvial plain and underlies many of eastern Arkansas's major towns.[52]

Northwest Arkansas is part of the Ozark Plateau including the Ozark Mountains, to the south are the Ouachita Mountains, and these regions are divided by the Arkansas River; the southern and eastern parts of Arkansas are called the Lowlands.[53] These mountain ranges are part of the U.S. Interior Highlands region, the only major mountainous region between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachian Mountains.[54] The state's highest point is Mount Magazine in the Ouachita Mountains,[55] which is 2,753 feet (839 m) above sea level.[6]

Arkansas is home to many caves, such as Blanchard Springs Caverns. The State Archeologist has catalogued more than 43,000 Native American living, hunting and tool-making sites, many of them Pre-Columbian burial mounds and rock shelters. Crater of Diamonds State Park near Murfreesboro is the world's only diamond-bearing site accessible to the public for digging.[56][57] Arkansas is home to a dozen Wilderness Areas totaling 158,444 acres (641.20 km2).[58] These areas are set aside for outdoor recreation and are open to hunting, fishing, hiking, and primitive camping. No mechanized vehicles nor developed campgrounds are allowed in these areas.[59]

Hydrology

[edit]

Arkansas has many rivers, lakes, and reservoirs within or along its borders. Major tributaries to the Mississippi River include the Arkansas River, the White River, and the St. Francis River.[60] The Arkansas is fed by the Mulberry and Fourche La Fave Rivers in the Arkansas River Valley, which is also home to Lake Dardanelle. The Buffalo, Little Red, Black and Cache Rivers are all tributaries to the White River, which also empties into the Mississippi. Bayou Bartholomew and the Saline, Little Missouri, and Caddo Rivers are all tributaries to the Ouachita River in south Arkansas, which empties into the Mississippi in Louisiana. The Red River briefly forms the state's boundary with Texas.[61] Arkansas has few natural lakes and many reservoirs,[quantify] such as Bull Shoals Lake, Lake Ouachita, Greers Ferry Lake, Millwood Lake, Beaver Lake, Norfork Lake, DeGray Lake, and Lake Conway.[62]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Arkansas's mix of warm temperate moist forest and subtropical bottomland is divided into three broad ecoregions: the Ozark, Ouachita-Appalachian Forests, the Mississippi Alluvial and Southeast USA Coastal Plains, and the Southeastern USA Plains.[63] The state is further divided into seven subregions: the Arkansas Valley, Boston Mountains, Mississippi Alluvial Plain, Mississippi Valley Loess Plain, Ozark Highlands, Ouachita Mountains, and the South Central Plains.[64] A 2010 United States Forest Service survey determined 18,720,000 acres (7,580,000 ha) of Arkansas's land is forestland, or 56% of the state's total area.[65] Dominant species in Arkansas's forests include Quercus (oak), Carya (hickory), Pinus echinata (shortleaf pine) and Pinus taeda (loblolly pine).[66][67]

Arkansas's plant life varies with its climate and elevation. The pine belt stretching from the Arkansas delta to Texas consists of dense oak-hickory-pine growth. Lumbering and paper milling activity is active throughout the region.[68] In eastern Arkansas, one can find Taxodium (cypress), Quercus nigra (water oaks), and hickories with their roots submerged in the Mississippi Valley bayous indicative of the Deep South. Saw palmetto and needle palm both range into Arkansas.[69] Nearby Crowley's Ridge is the only home of the tulip tree in the state, and generally hosts more northeastern plant life such as the beech tree.[70] The northwestern highlands are covered in an oak-hickory mixture, with Ozark white cedars, cornus (dogwoods), and Cercis canadensis (redbuds) also present. The higher peaks in the Arkansas River Valley play host to scores of ferns, including the Physematium scopulinum and Adiantum (maidenhair fern) on Mount Magazine.[71] The white-tailed deer is the official state mammal.[72]

Climate

[edit]

Arkansas generally has a humid subtropical climate. While not bordering the Gulf of Mexico, Arkansas, is still close enough to the warm, large body of water for it to influence the weather in the state. Generally, Arkansas, has hot, humid summers and slightly drier, mild to cool winters. In Little Rock, the daily high temperatures average around 93 °F (34 °C) with lows around 73 °F (23 °C) in July. In January highs average around 51 °F (11 °C) and lows around 32 °F (0 °C). In Siloam Springs in the northwest part of the state, the average high and low temperatures in July are 89 and 67 °F (32 and 19 °C) and in January the average high and low are 44 and 23 °F (7 and −5 °C). Annual precipitation throughout the state averages between about 40 and 60 inches (1,000 and 1,500 mm); it is somewhat wetter in the south and drier in the northern part of the state.[73] Snowfall is infrequent but most common in the northern half of the state.[60] The half of the state south of Little Rock is more apt to see ice storms. Arkansas's record high is 120 °F (49 °C) at Ozark on August 10, 1936; the record low is −29 °F (−34 °C) at Gravette, on February 13, 1905.[74]

Arkansas is known for extreme weather and frequent storms. A typical year brings thunderstorms, tornadoes, and hail. Occasional cold snaps stand to bring varying amounts of snow, as well as ice storms. Between both the Great Plains and the Gulf States, Arkansas, receives around 60 days of thunderstorms. Arkansas is located in Dixie alley, and very near tornado alley. As a result, a few of the most destructive tornadoes in U.S. history have struck the state. While sufficiently far from the coast to avoid a direct hit from a hurricane, Arkansas can often get the remnants of a tropical system, which dumps tremendous amounts of rain in a short time and often spawns smaller tornadoes.[citation needed]

| Monthly Normal High and Low Temperatures For Various Arkansas Cities | |||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fayetteville[75] | 44/24 (7/-4) |

51/29 (10/-2) |

59/38 (15/3) |

69/46 (20/8) |

76/55 (24/13) |

84/64 (29/18) |

89/69 (32/20) |

89/67 (32/19) |

81/59 (27/15) |

70/47 (21/9) |

57/37 (14/3) |

48/28 (9/-2) |

68/47 (20/8) |

| Jonesboro[76] | 45/26 (7/-3) |

51/30 (11/-1) |

61/40 (16/4) |

71/49 (22/9) |

80/58 (26/15) |

88/67 (31/19) |

92/71 (34/22) |

91/69 (33/20) |

84/61 (29/16) |

74/49 (23/9) |

60/39 (15/4) |

49/30 (10/-1) |

71/49 (21/9) |

| Little Rock[77] | 51/31 (11/-1) |

55/35 (13/2) |

64/43 (18/6) |

73/51 (23/11) |

81/61 (27/16) |

89/69 (32/21) |

93/73 (34/23) |

93/72 (34/22) |

86/65 (30/18) |

75/53 (24/12) |

63/42 (17/6) |

52/34 (11/1) |

73/51 (23/11) |

| Texarkana[78] | 53/31 (11/-1) |

58/34 (15/1) |

67/42 (19/5) |

75/50 (24/10) |

82/60 (28/16) |

89/68 (32/20) |

93/72 (34/22) |

93/71 (34/21) |

86/64 (30/18) |

76/52 (25/11) |

64/41 (18/5) |

55/33 (13/1) |

74/52 (23/11) |

| Monticello[79] | 52/30 (11/-1) |

58/34 (14/1) |

66/43 (19/6) |

74/49 (23/10) |

82/59 (28/15) |

89/66 (32/19) |

92/70 (34/21) |

92/68 (33/20) |

86/62 (30/17) |

76/50 (25/10) |

64/41 (18/5) |

55/34 (13/1) |

74/51 (23/10) |

| Fort Smith[80] | 48/27 (8/-2) |

54/32 (12/0) |

64/40 (17/4) |

73/49 (22/9) |

80/58 (26/14) |

87/67 (30/19) |

92/71 (33/21) |

92/70 (33/21) |

84/62 (29/17) |

75/50 (23/10) |

61/39 (16/4) |

50/31 (10/0) |

72/50 (22/10) |

| Average high °F/average low °F (average high °C/average low°C) | |||||||||||||

Cities and towns

[edit]

Little Rock has been Arkansas's capital city since 1821 when it replaced Arkansas Post as the capital of the Territory of Arkansas.[81] The state capitol was moved to Hot Springs and later Washington during the American Civil War when the Union armies threatened the city in 1862, and state government did not return to Little Rock until after the war ended. Today, the Little Rock–North Little Rock–Conway metropolitan area is the largest in the state, with a population of 724,385 in 2013.[82]

The Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers Metropolitan Area is the second-largest metropolitan area in Arkansas, growing at the fastest rate due to the influx of businesses and the growth of the University of Arkansas and Walmart.[83]

The state has eight cities with populations above 50,000 (based on 2010 census). In descending order of size, they are Little Rock, Fort Smith, Fayetteville, Springdale, Jonesboro, North Little Rock, Conway, and Rogers. Of these, only Fort Smith and Jonesboro are outside the two largest metropolitan areas. Other cities in Arkansas include Pine Bluff, Crossett, Bryant, Lake Village, Hot Springs, Bentonville, Texarkana, Sherwood, Jacksonville, Russellville, Bella Vista, West Memphis, Paragould, Cabot, Searcy, Van Buren, El Dorado, Blytheville, Harrison, Dumas, Rison, Warren, and Mountain Home.[84]

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Little Rock | Pulaski | 198,606 | 11 | Hot Springs | Garland | 36,915 | ||

| 2 | Fort Smith | Sebastian | 88,037 | 12 | Benton | Saline | 35,789 | ||

| 3 | Fayetteville | Washington | 85,257 | 13 | Sherwood | Pulaski | 31,081 | ||

| 4 | Springdale | Washington | 79,599 | 14 | Texarkana | Miller | 30,259 | ||

| 5 | Jonesboro | Craighead | 75,866 | 15 | Russellville | Pope | 29,318 | ||

| 6 | Rogers | Benton | 66,430 | 16 | Jacksonville | Pulaski | 28,513 | ||

| 7 | North Little Rock | Pulaski | 65,911 | 17 | Bella Vista | Benton | 28,511 | ||

| 8 | Conway | Faulkner | 65,782 | 18 | Paragould | Greene | 28,488 | ||

| 9 | Bentonville | Benton | 49,298 | 19 | Cabot | Lonoke | 26,141 | ||

| 10 | Pine Bluff | Jefferson | 42,984 | 20 | West Memphis | Crittenden | 24,860 | ||

Demographics

[edit]Population

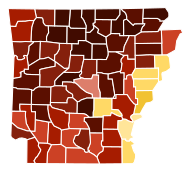

[edit]Right: Map showing population changes by county between 2000 and 2010. Blue indicates population gain, purple indicates population loss, and shade indicates magnitude.

The United States Census Bureau estimated that the population of Arkansas was 3,017,804 on July 1, 2019, a 3.49% increase since the 2010 United States census.[86] At the 2020 U.S. census, Arkansas had a resident population of 3,011,524.

From fewer than 15,000 in 1820, Arkansas's population grew to 52,240 during a special census in 1835, far exceeding the 40,000 required to apply for statehood.[87] Following statehood in 1836, the population doubled each decade until the 1870 census conducted following the American Civil War. The state recorded growth in each successive decade, although it gradually slowed in the 20th century.

It recorded population losses in the 1950 and 1960 censuses. This outmigration was a result of multiple factors, including farm mechanization, decreasing labor demand, and young educated people leaving the state due to a lack of non-farming industry in the state.[88] Arkansas again began to grow, recording positive growth rates ever since and exceeding two million by the 1980 census.[89] Arkansas's rate of change, age distributions, and gender distributions mirror national averages. Minority group data also approximates national averages. There are fewer people in Arkansas of Hispanic or Latino origin than the national average.[90] The center of population of Arkansas for 2000 was located in Perry County, near Nogal.[91]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 2,459 homeless people in Arkansas.[92][93]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 1,062 | — | |

| 1820 | 14,273 | 1,244.0% | |

| 1830 | 30,388 | 112.9% | |

| 1840 | 97,574 | 221.1% | |

| 1850 | 209,897 | 115.1% | |

| 1860 | 435,450 | 107.5% | |

| 1870 | 484,471 | 11.3% | |

| 1880 | 802,525 | 65.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,128,211 | 40.6% | |

| 1900 | 1,311,564 | 16.3% | |

| 1910 | 1,574,449 | 20.0% | |

| 1920 | 1,752,204 | 11.3% | |

| 1930 | 1,854,482 | 5.8% | |

| 1940 | 1,949,387 | 5.1% | |

| 1950 | 1,909,511 | −2.0% | |

| 1960 | 1,786,272 | −6.5% | |

| 1970 | 1,923,295 | 7.7% | |

| 1980 | 2,286,435 | 18.9% | |

| 1990 | 2,350,725 | 2.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,673,400 | 13.7% | |

| 2010 | 2,915,918 | 9.1% | |

| 2020 | 3,011,524 | 3.3% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 3,088,354 | [94] | 2.6% |

| Source: 1910–2020[95] | |||

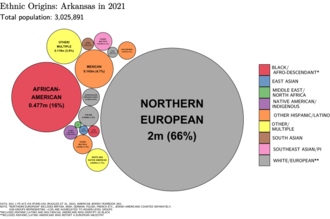

Race and ethnicity

[edit]Per the 2019 census estimates, Arkansas was 72.0% non-Hispanic white, 15.4% Black or African American, 0.5% American Indian and Alaska Native, 1.5% Asian, 0.4% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 0.1% some other race, 2.4% two or more races, and 7.7% Hispanic or Latin American of any race.[96] In 2011, the state was 80.1% white (74.2% non-Hispanic white), 15.6% Black or African American, 0.9% American Indian and Alaska Native, 1.3% Asian, and 1.8% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race made up 6.6% of the population.[90] As of 2011, 39.0% of Arkansas's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[97]

| Race and ethnicity[98] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 68.5% | 73.2% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 14.9% | 16.2% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[d] | — | 8.5% | ||

| Asian | 1.7% | 2.2% | ||

| Native American | 0.7% | 3.4% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.5% | 0.6% | ||

| Other | 0.3% | 1.1% | ||

Non-Hispanic White 40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%90%+Black or African American 40–50%50–60%60–70%

| Racial composition | 1990[99] | 2000[100] | 2010[101] | 2020[102] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 82.7% | 80.0% | 77.0% | 70.2% |

| African American | 15.9% | 15.7% | 15.4% | 15.1% |

| Asian | 0.5% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Native | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.9% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.5% |

| Other race | 0.3% | 1.5% | 3.4% | 4.5% |

| Two or more races | – | 1.3% | 2.0% | 7.1% |

European Americans have a strong presence in the northwestern Ozarks and the central part of the state. African Americans live mainly in the southern and eastern parts of the state. Arkansans of Irish, English and German ancestry are mostly found in the far northwestern Ozarks near the Missouri border. Ancestors of the Irish in the Ozarks were chiefly Scots-Irish, Protestants from Northern Ireland, the Scottish lowlands and northern England part of the largest group of immigrants from Great Britain and Ireland before the American Revolution. English and Scots-Irish immigrants settled throughout the back country of the South and in the more mountainous areas. Americans of English stock are found throughout the state.[103]

A 2010 survey of the principal ancestries of Arkansas's residents revealed the following:[104] 15.5% African American, 12.3% Irish, 11.5% German, 11.0% American, 10.1% English, 4.7% Mexican, 2.1% French, 1.7% Scottish, 1.7% Dutch, 1.6% Italian, and 1.4% Scots-Irish.

Most people identifying as "American" are of English descent or Scots-Irish descent. Their families have been in the state so long, in many cases since before statehood, that they choose to identify simply as having American ancestry or do not in fact know their ancestry. Their ancestry primarily goes back to the original 13 colonies and for this reason many of them today simply claim American ancestry. Many people who identify as of Irish descent are in fact of Scots-Irish descent.[105][106][107][108]

According to the American Immigration Council, in 2015, the top countries of origin for Arkansas' immigrants were Mexico, El Salvador, India, Vietnam, and Guatemala.[109]

According to the 2006–2008 American Community Survey, 93.8% of Arkansas's population (over the age of five) spoke only English at home. About 4.5% of the state's population spoke Spanish at home. About 0.7% of the state's population spoke another Indo-European language. About 0.8% of the state's population spoke an Asian language, and 0.2% spoke other languages.[clarification needed dubious]

Religion

[edit]Like most other Southern states, Arkansas is part of the Bible Belt and predominantly Protestant. The largest denominations by number of adherents in 2010 were the Southern Baptist Convention with 661,382; the United Methodist Church with 158,574; non-denominational Evangelical Protestants with 129,638; the Catholic Church with 122,662; and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 31,254. Other religions include Islam, Judaism, Wicca/Paganism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and some residents have no religious affiliation.[111]

In 2014, the Pew Research Center determined that 79% of the population was Christian, dominated by evangelicals in the Southern Baptist and independent Baptist churches. In contrast with many other states, the Catholic Church as of 2014 was not the largest Christian denomination in Arkansas. Of the unaffiliated population, 2% were atheist in 2014.[110] By 2020, the Public Religion Research Institute determined 71% of the population was Christian.[112] Arkansas continued to be dominated by evangelicals, followed by mainline Protestants and historically black or African American churches.

Economy

[edit]

Once a state with a cashless society in the uplands and plantation agriculture in the lowlands, Arkansas's economy has evolved and diversified. The state's gross domestic product (GDP) was $176.24 billion in 2023.[113] Six Fortune 500 companies are based in Arkansas, including the #1 company atop the list, the mega-retailer Walmart, founded by Sam Walton in 1962, and headquartered in Bentonville.[114] The per capita personal income in 2023 was $54,347, ranking 46th in the nation, and the median household income was $55,432, which ranked 47th.[115][116] The state's agriculture outputs are poultry and eggs, soybeans, sorghum, cattle, cotton, rice, hogs, and milk. Its industrial outputs are food processing, electric equipment, fabricated metal products, machinery, and paper products. Arkansas's mines produce natural gas, oil, crushed stone, bromine, and vanadium.[117] According to CNBC, Arkansas is the 20th-best state for business, with the 2nd-lowest cost of doing business, 5th-lowest cost of living, 11th-best workforce, 20th-best economic climate, 28th-best-educated workforce, 31st-best infrastructure and the 32nd-friendliest regulatory environment.[citation needed] Arkansas gained 12 spots in the best state for business rankings since 2011.[118] As of 2014, it was the most affordable state to live in.[citation needed]

As of July 2023, the state's unemployment rate was 2.6%; the preliminary rate for December 2023 is 3.4%.[119]

Industry and commerce

[edit]Arkansas's earliest industries were fur trading and agriculture, with development of cotton plantations in the areas near the Mississippi River. They were dependent on slave labor through the American Civil War.[120]

Today only about three percent of the population are employed in the agricultural sector,[121] it remains a major part of the state's economy, ranking 13th in the nation in the value of products sold.[122] Arkansas is the nation's largest producer of rice, broilers, and turkeys,[123] and ranks in the top three for cotton, pullets, and aquaculture (catfish).[122] Forestry remains strong in the Arkansas Timberlands, and the state ranks fourth nationally and first in the South in softwood lumber production.[124] Automobile parts manufacturers have opened factories in eastern Arkansas to support auto plants in other states. Bauxite was formerly a large part of the state's economy, mined mostly around Saline County.[125]

Tourism is also very important to the Arkansas economy; the official state nickname "The Natural State" was created for state tourism advertising in the 1970s, and is still used to this day. The state maintains 52 state parks and the National Park Service maintains seven properties in Arkansas. The completion of the William Jefferson Clinton Presidential Library in Little Rock has drawn many visitors to the city and revitalized the nearby River Market District. Many cities also hold festivals, which draw tourists to Arkansas culture, such as The Bradley County Pink Tomato Festival in Warren, King Biscuit Blues Festival, Ozark Folk Festival, Toad Suck Daze, and Tontitown Grape Festival.[126]

Transportation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Transportation in Arkansas is overseen by the Arkansas Department of Transportation (ArDOT), headquartered in Little Rock. Several main corridors pass through Little Rock, including Interstate 30 (I-30) and I-40 (the nation's 3rd-busiest trucking corridor).[127] Arkansas first designated a state highway system in 1924, and first numbered its roads in 1926. Arkansas had one of the first paved roads, the Dollarway Road, and one of the first members of the Interstate Highway System. The state maintains a large system of state highways today, in addition to eight Interstates and 20 U.S. Routes.

In northeast Arkansas, I-55 travels north from Memphis to Missouri, with a new spur to Jonesboro (I-555). Northwest Arkansas is served by the segment of I-49 from Fort Smith to the beginning of the Bella Vista Bypass. This segment of I-49 currently follows mostly the same route as the former section of I-540 that extended north of I-40.[128] The state also has the 13th largest state highway system in the nation.[129]

Arkansas is served by 2,750 miles (4,430 km) of railroad track divided among twenty-six railroad companies including three Class I railroads.[130] Freight railroads are concentrated in southeast Arkansas to serve the industries in the region. The Texas Eagle, an Amtrak passenger train, serves five stations in the state Walnut Ridge, Little Rock, Malvern, Arkadelphia, and Texarkana.

Arkansas also benefits from the use of its rivers for commerce. The Mississippi River and Arkansas River are both major rivers. The United States Army Corps of Engineers maintains the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, allowing barge traffic up the Arkansas River to the Port of Catoosa in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

There are four airports with commercial service: Clinton National Airport (formerly Little Rock National Airport or Adams Field), Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport, Fort Smith Regional Airport, and Texarkana Regional Airport, with dozens of smaller airports in the state.

Intercity bus services across the state are provided by Flixbus, Greyhound Lines, and Jefferson Lines.[131][132]

Public transit and community transport services for the elderly or those with developmental disabilities are provided by agencies such as the Central Arkansas Transit Authority and the Ozark Regional Transit, organizations that are part of the Arkansas Transit Association.

| Local transit map |

|---|

Government

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

As with the federal government of the United States, political power in Arkansas is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. Each officer's term is four years long. Office holders are term-limited to two full terms plus any partial terms before the first full term.[133]

Executive

[edit]The governor of Arkansas is Sarah Huckabee Sanders. Sanders is a Republican and was inaugurated on January 10, 2023.[134][135] The six other elected executive positions in Arkansas are lieutenant governor, secretary of state, attorney general, treasurer, auditor, and land commissioner.[136] The governor also appoints the leaders of various state boards, committees, and departments. Arkansas governors served two-year terms until a referendum lengthened the term to four years, effective with the 1986 election. Individuals elected to these offices are limited to a lifetime total of two four-year terms per office.

In Arkansas, the lieutenant governor is elected separately from the governor and thus can be from a different political party.[137]

Legislative

[edit]The Arkansas General Assembly is the state's bicameral bodies of legislators, composed of the Senate and House of Representatives. The Senate contains 35 members from districts of approximately equal population. These districts are redrawn decennially with each US census, and in election years ending in "2", the entire body is put up for reelection. Following the election, half of the seats are designated as two-year seats and are up for reelection again in two years, these "half-terms" do not count against a legislator's term limits. The remaining half serve a full four-year term. This staggers elections such that half the body is up for reelection every two years and allows for complete body turnover following redistricting.[138] Arkansas House members can serve a maximum of three two-year terms. House districts are redistricted by the Arkansas Board of Apportionment.

In the 2012 elections, Arkansas voters elected a 21–14 Republican majority in the Senate and the Republicans gained a 51–49 majority in the House of Representatives.[139] The 2012 elections established a Republican dominance in both bodies of legislature.

The Republican Party's majority status in the Arkansas State House of Representatives after the 2012 elections, is the party's first since 1874. Arkansas was the last state of the old Confederacy to not have Republican control of either chamber of its house since the American Civil War.[140]

Following the term limits changes, studies have shown that lobbyists have become less influential in state politics. Legislative staff, not subject to term limits, have acquired additional power and influence due to the high rate of elected official turnover.[133]

Judicial

[edit]Arkansas's judicial branch has five court systems: Arkansas Supreme Court, Arkansas Court of Appeals, Circuit Courts, District Courts and City Courts.

Most cases begin in district court, which is subdivided into state district court and local district court. State district courts exercise district-wide jurisdiction over the districts created by the General Assembly, and local district courts are presided over by part-time judges who may privately practice law. 25 state district court judges preside over 15 districts, with more districts created in 2013 and 2017. There are 28 judicial circuits of Circuit Court, with each contains five subdivisions: criminal, civil, probate, domestic relations, and juvenile court. The jurisdiction of the Arkansas Court of Appeals is determined by the Arkansas Supreme Court, and there is no right of appeal from the Court of Appeals to the high court. The Arkansas Supreme Court can review Court of Appeals cases upon application by either a party to the litigation, upon request by the Court of Appeals, or if the Arkansas Supreme Court feels the case should have been initially assigned to it. The twelve judges of the Arkansas Court of Appeals are elected from judicial districts to renewable six-year terms.

The Arkansas Supreme Court is the court of last resort in the state, composed of seven justices elected to eight-year terms. Established by the Arkansas Constitution in 1836, the court's decisions can be appealed to only the Supreme Court of the United States.

Federal

[edit]Both Arkansas's U.S. senators, John Boozman and Tom Cotton, are Republicans. The state has four seats in U.S. House of Representatives. All four seats are held by Republicans: Rick Crawford (1st district), French Hill (2nd district), Steve Womack (3rd district), and Bruce Westerman (4th district).[141]

Politics

[edit]| Party registration as of October 3, 2024[142][143] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total voters | Percentage | |||

| Nonpartisan | 1,581,556 | 87.59% | |||

| Republican | 140,291 | 7.47% | |||

| Democratic | 88,969 | 4.89% | |||

| Other | 851 | 0.05% | |||

| Total | 1,811,667 | 100.00% | |||

Arkansas governor Bill Clinton brought national attention to the state with a long speech at the 1988 Democratic National Convention endorsing Michael Dukakis. Some journalists suggested the speech was a threat to his ambitions; Clinton defined it "a comedy of error, just one of those fluky things".[144]

He won the Democratic nomination for president in 1992. Clinton presented himself as a "New Democrat" and used incumbent George H. W. Bush's broken promise against him to win the 1992 presidential election with 43.0% of the vote to Bush's 37.5% and independent billionaire Ross Perot's 18.9%.

Most Republican strength traditionally lay mainly in the northwestern part of the state, particularly Fort Smith and Bentonville, as well as North Central Arkansas around the Mountain Home area. In the latter area, Republicans have been known to get 90% or more of the vote, while the rest of the state was more Democratic. After 2010, Republican strength expanded further to the Northeast and Southwest and into the Little Rock suburbs. The Democrats are mostly concentrated to central Little Rock, the Mississippi Delta, the Pine Bluff area, and the areas around the southern border with Louisiana.

Arkansas has elected only three Republicans to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction: Tim Hutchinson, who was defeated after one term by Mark Pryor; John Boozman, who defeated incumbent Blanche Lincoln; and Tom Cotton, who defeated Pryor in 2014. Before 2013, the General Assembly had not been controlled by the Republican Party since Reconstruction, with the GOP holding a 51-seat majority in the state House and a 21-seat (of 35) in the state Senate following victories in 2012. Arkansas was one of the only states of the former Confederacy other than Florida and Virginia that sent two Democrats to the U.S. Senate for any period during the first decade of the 21st century.

In 2010, Republicans captured three of the state's four seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 2012, they won election to all four House seats. Arkansas held the distinction of having a U.S. House delegation composed entirely of military veterans (Rick Crawford, Army; Tim Griffin, Army Reserve; Steve Womack, National Guard; Tom Cotton, Army). When Pryor was defeated in 2014, the entire congressional delegation was in GOP hands for the first time since Reconstruction.

Reflecting the state's large evangelical population, Arkansas has a strong social conservative bent. In the aftermath of the landmark Supreme Court decision Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, Arkansas became one of nine states where abortion is banned.[145] Under the Arkansas Constitution, Arkansas is a right to work state. Its voters passed a ban on same-sex marriage in 2004, with 75% voting yes,[146] although that ban has been inactive since the Supreme Court protected same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Arkansas retains the death penalty. Authorized methods of execution include the electric chair.[147]

Military

[edit]The Strategic Air Command facility of Little Rock Air Force Base was one of eighteen silos in the command of the 308th Strategic Missile Wing (308th SMW), specifically one of the nine silos within its 374th Strategic Missile Squadron (374th SMS). The squadron was responsible for Launch Complex 374–7, site of the 1980 explosion of a Titan II Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) in Damascus, Arkansas.[148]

Taxation

[edit]Taxes are collected by the Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration.[149]

Health

[edit]

As of 2012, Arkansas, as with many Southern states, has a high incidence of premature death, infant mortality, cardiovascular deaths, and occupational fatalities compared to the rest of the United States.[150] The state is tied for 43rd with New York in percentage of adults who regularly exercise.[151] Arkansas is usually ranked as one of the least healthy states due to high obesity, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle rates,[150] but according to a Gallup poll, Arkansas made the most immediate progress in reducing its number of uninsured residents after the Affordable Care Act passed. The percentage of uninsured in Arkansas dropped from 22.5 in 2013 to 12.4 in August 2014.[152]

The Arkansas Clean Indoor Air Act, a statewide smoking ban excluding bars and some restaurants, went into effect in 2006.[153]

Healthcare in Arkansas is provided by a network of hospitals as members of the Arkansas Hospital Association. Major institutions with multiple branches include Baptist Health, Community Health Systems, and HealthSouth. The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) in Little Rock operates the UAMS Medical Center, a teaching hospital ranked as high performing nationally in cancer and nephrology.[154] The pediatric division of UAMS Medical Center is known as Arkansas Children's Hospital, nationally ranked in pediatric cardiology and heart surgery.[155] Together, these two institutions are the state's only Level I trauma centers.[156]

Education

[edit]Arkansas has 1,064 state-funded kindergartens, elementary, junior and senior high schools.[157]

The state supports a network of public universities and colleges, including two major university systems: Arkansas State University System and University of Arkansas System. The University of Arkansas, flagship campus of the University of Arkansas System in Fayetteville was ranked #63 among public schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report.[158] Other public institutions include Arkansas State University, University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, Arkansas Tech University, Henderson State University, Southern Arkansas University, and University of Central Arkansas across the state. It is also home to 11 private colleges and universities including Hendrix College, one of the nation's top 100 liberal arts colleges, according to U.S. News & World Report.[159]

In the 1920s the state required all children to attend public schools. The school year was set at 131 days, although some areas were unable to meet that requirement.[160][161]

Generally prohibited in the Western world at large, school corporal punishment is not unusual in Arkansas, with 20,083 public school students[e] paddled at least one time, according to government data for the 2011–12 school year.[162] The rate of corporal punishment in public schools is higher only in Mississippi.[162]

Media

[edit]As of 2010 many Arkansas local newspapers are owned by WEHCO Media, Alabama-based Lancaster Management, Kentucky-based Paxton Media Group, Missouri-based Rust Communications, Nevada-based Stephens Media, and New York-based GateHouse Media.[163]

Culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

The culture of Arkansas includes distinct cuisine, dialect, and traditional festivals. Sports are also very important to the culture, including football, baseball, basketball, hunting, and fishing. Perhaps the best-known aspect of Arkansas's culture is the stereotype that its citizens are shiftless hillbillies.[164] The reputation began when early explorers characterized the state as a savage wilderness full of outlaws and thieves.[165] The most enduring icon of Arkansas's hillbilly reputation is The Arkansas Traveller, a painted depiction of a folk tale from the 1840s.[166] Though intended to represent the divide between rich southeastern plantation Arkansas planters and the poor northwestern hill country, the meaning was twisted to represent a Northerner lost in the Ozarks on a white horse asking a backwoods Arkansan for directions.[167] The state also suffers from the racial stigma common to former Confederate states, with historical events such as the Little Rock Nine adding to Arkansas's enduring image.[168]

Art and history museums display pieces of cultural value for Arkansans and tourists to enjoy. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville was visited by 604,000 people in 2012, its first year.[169] The museum includes walking trails and educational opportunities in addition to displaying over 450 works covering five centuries of American art.[170] Several historic town sites have been restored as Arkansas state parks, including Historic Washington State Park, Powhatan Historic State Park, and Davidsonville Historic State Park.

Arkansas features a variety of native music across the state, ranging from the blues heritage of West Memphis, Pine Bluff, Helena–West Helena to rockabilly, bluegrass, and folk music from the Ozarks. Festivals such as the King Biscuit Blues Festival and Bikes, Blues, and BBQ pay homage to the history of blues in the state. The Ozark Folk Festival in Mountain View is a celebration of Ozark culture and often features folk and bluegrass musicians. Literature set in Arkansas such as I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou and A Painted House by John Grisham describe the culture at various time periods.

Sports and recreation

[edit]

Team sports and especially collegiate football are important to Arkansans. College football in Arkansas began from humble beginnings, when the University of Arkansas first fielded a team in 1894. Over the years, many Arkansans have looked to Arkansas Razorbacks football as the public image of the state.[171] Although the University of Arkansas is based in Fayetteville, the Razorbacks have always played at least one game per season at War Memorial Stadium in Little Rock in an effort to keep fan support in central and south Arkansas.

Arkansas State University became the second NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) (then known as Division I-A) team in the state in 1992 after playing in lower divisions for nearly two decades. The two schools have never played each other, due to the University of Arkansas's policy of not playing intrastate games.[172] Two other campuses of the University of Arkansas System are Division I members. The University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff is a member of the Southwestern Athletic Conference, a league whose members all play football in the second-level Football Championship Subdivision (FCS). The University of Arkansas at Little Rock, known for sports purposes as Little Rock, joined the Ohio Valley Conference in 2022 after playing in the Sun Belt Conference; unlike many other OVC members, it does not field a football program. The state's other Division I member is the University of Central Arkansas (UCA), which joined the ASUN Conference in 2021 after leaving the FCS Southland Conference. Because the ASUN does not plan to start FCS football competition until at least 2022, UCA football is competing in the Western Athletic Conference as part of a formal football partnership between the two leagues. Seven of Arkansas's smaller colleges play in NCAA Division II, with six in the Great American Conference and one in the MIAA. Two other small Arkansas colleges compete in NCAA Division III, in which athletic scholarships are prohibited. High school football also began to grow in Arkansas in the early 20th century.

Baseball runs deep in Arkansas and was popular before the state hosted Major League Baseball (MLB) spring training in Hot Springs from 1886 to the 1920s. Two minor league teams are based in the state. The Arkansas Travelers play at Dickey–Stephens Park in North Little Rock, and the Northwest Arkansas Naturals play in Arvest Ballpark in Springdale. Both teams compete in the Texas League.

Hunting continues in the state. The state created the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission in 1915 to regulate hunting.[173] Today a significant portion of Arkansas's population participates in hunting duck in the Mississippi flyway and deer across the state.[174] Ducks Unlimited has called Stuttgart, Arkansas, "the epicenter of the duck universe".[175] Millions of acres of public land are available for both bow and modern gun hunters.[174]

Fishing has always been popular in Arkansas,[176] and the sport and the state have benefited from the creation of reservoirs across the state. Following the completion of Norfork Dam, the Norfork Tailwater and the White River have become a destination for trout fishers. Several smaller retirement communities such as Bull Shoals, Hot Springs Village, and Fairfield Bay have flourished due to their position on a fishing lake. The National Park Service has preserved the Buffalo National River in its natural state and fly fishers visit it annually.

Attractions

[edit]

- Arkansas Post National Memorial at Gillett

- Blanchard Springs Caverns

- Bull Shoals Caverns

- Buffalo National River

- Quigley's Castle

- Mammoth Spring State Park

- Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum

- Fort Smith National Historic Site

- Hot Springs National Park

- Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

- Pea Ridge National Military Park

- President William Jefferson Clinton Birthplace Home National Historic Site

- Arkansas State Capitol Building

- List of Arkansas state parks

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988

- ^ The Geographic Names Index System (GNIS) of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) indicates that the official name of this feature is Magazine Mountain, not "Mount Magazine". Although not a hard and fast rule, generally "Mount X" is used for a peak and "X Mountain" is more frequently used for ridges, which better describes this feature. Magazine Mountain appears in the GNIS as a ridge,[5] with Signal Hill identified as its summit.[6] "Mount Magazine" is the name used by the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, which follows what the locals have used since the area was first settled.

- ^ a b c d e

The region was organized as the Territory of Arkansaw on July 4, 1819, but the territory was admitted to the United States as the state of Arkansas on June 15, 1836. The name was historically pronounced /ˈɑːrkənsɔː/, /ɑːrˈkænzəs/, and several other variants. The residents of Arkansas have called themselves either "Arkansans" or "Arkansawyers". In 1881, the Arkansas General Assembly passed the following concurrent resolution, now Arkansas Code April 1 105:[20]

Whereas, confusion of practice has arisen in the pronunciation of the name of our state and it is deemed important that the true pronunciation should be determined for use in oral official proceedings.

And, whereas, the matter has been thoroughly investigated by the State Historical Society and the Eclectic Society of Little Rock, which have agreed upon the correct pronunciation as derived from history, and the early usage of the American immigrants.

Be it therefore resolved by both houses of the General Assembly, that the only true pronunciation of the name of the state, in the opinion of this body, is that received by the French from the native Indians and committed to writing in the French word representing the sound. It should be pronounced in three (3) syllables, with the final "s" silent, the "a" in each syllable with the Italian sound, and the accent on the first and last syllables. The pronunciation with the accent on the second syllable with the sound of "a" in "man" and the sounding of the terminal "s" is discouraged by Arkansans.

Despite this, the state's name is still frequently mispronounced, especially by non-Americans; in fact, it is spelled in Cyrillic with the ar-KAN-zəs pronunciation.

Citizens of the state of Kansas often pronounce the Arkansas River as /ɑːrˈkænzəs/, in a manner similar to the common pronunciation of the name of their state.

- ^ Persons of Hispanic or Latino origin are not distinguished between total and partial ancestry.

- ^ This figure refers to only the number of students paddled, regardless of whether a student was spanked multiple times in a year, and does not refer to the number of instances of corporal punishment, which would be substantially higher.

References

[edit]- ^ "United States Census Quick Facts Arkansas". Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ "Household Income in States and Metropolitan Areas: 2023" (PDF). Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ "Mag". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Magazine Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ a b "Signal Hill". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ "United States Census Quick Facts Arkansas". Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ "Household Income in States and Metropolitan Areas: 2023" (PDF). Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ Blevins 2009, p. 2.

- ^ "2020 Arkansas Code Title 1 - General Provisions Chapter 4 - State Symbols, Motto, Etc. § 1-4-117. Official language". Justia US Law. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (1997) English Pronouncing Dictionary, 15th ed. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45272-4.

- ^ a b "Census Regions and Divisions of the United States" (PDF). Geography Division, United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ Lyon, Owen (Autumn 1950). "The Trail of the Quapaw". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 9 (3): 206–7. doi:10.2307/40017228. ISSN 0004-1823. JSTOR 40017228.

- ^ Cash, Marie (December 1943). "Arkansas Achieves Statehood". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 2 (4): 292–308. doi:10.2307/40018776. JSTOR 40018776.

- ^ "2020 Census Apportionment Results". The United States Census Bureau. April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Mailing Address: 301 Parker Ave Fort; Us, AR 72901 Phone: 479 783-3961 Contact. "Judge Isaac C. Parker - Fort Smith National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bright, William (2007). Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-806135984.

- ^ "Arkansas Secretary of State". www.sos.arkansas.gov. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ "Origin of Names of US States". Bureau of Indian Affairs. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ "Code". Arkansas State Legislature (1–4–105). AR, US: Assembly. Archived from the original (official text) on September 24, 2011.

- ^ Liberman, Mark (March 10, 2007). "Arkansas apostrophism". Language Log. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Declaring "Arkansas's" as the correct spelling of the possessive form of the name of our state (PDF) (House Concurrent Resolution). Arkansas House of Representatives. March 14, 2007.

- ^ Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. pp. 341–351. ISBN 9780820318882.

- ^ Davidson, James West. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection Volume 1. Mc Graw Hill, New York 2010, Chapter 1, p. 2,3

- ^ Sabo III, George (December 12, 2008). "First Encounters, Hernando de Soto in the Mississippi Valley, 1541–42". Retrieved May 3, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Fletcher 1989, p. 26.

- ^ a b Arnold 1992, p. 75.

- ^ "Linguist list 14.4". Listserv.linguistlist.org. February 11, 2003. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Arnold et al. 2002, p. 82.

- ^ Din, Gilbert C. (Spring 1981). "Arkansas Post in the American Revolution". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 40 (1): 17–28. doi:10.2307/40023280. JSTOR 40023280.

- ^ Arnold et al. 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Johnson 1965, p. 58.

- ^ Bolton, S. Charles (Spring 1999). "Slavery and the Defining of Arkansas". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 58 (1): 9. doi:10.2307/40026271. JSTOR 40026271.

- ^ Scroggs 1961, pp. 231–232.

- ^ "3c Arkansas Centennial state houses single". ' Smithsonian National Postal Museum. 1936. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ White 1962, p. 197.

- ^ Eno, Clara B. (Winter 1945). "Territorial Governors of Arkansas". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 4 (4): 278. doi:10.2307/40018362. JSTOR 40018362.

- ^ Scroggs 1961, p. 243.

- ^ Historical Census Browser, 1860 US Census, University of Virginia Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Arnold et al. 2002, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Bolton 1999, p. 22.

- ^ Arnold et al. 2002, p. 200.

- ^ "Brooks-Baxter War—Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ William D. Baker, Minority Settlement in the Mississippi River Counties of the Arkansas Delta, 1870–1930 Archived May 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Arkansas Preservation Commission. Retrieved May 14, 2008

- ^ "White Primary" System Bars Blacks from Politics—1900, The Arkansas News, Old State House, Spring 1987, p.3. Retrieved March 22, 2008. Archived January 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Elaine Massacre, Arkansas Encyclopedia of History and Culture; accessed April 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Japanese American Relocation Camps—Encyclopedia of Arkansas". encyclopediaofarkansas.net.

- ^ "Little Rock Nine—Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ Smith 1989, p. 15.

- ^ Smith 1989, pp. 15–17.

- ^ "Arkansas Regions". Discover Arkansas History. The Department of Arkansas Heritage. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ Smith 1989, p. 19.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project 1987, p. 6.

- ^ "Ozark Mountains". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ "Arkansas's Highpoint Information" (PDF). Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ "Crater of Diamonds: History of diamonds, diamond mining in Arkansas". Craterofdiamondsstatepark.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ "US Diamond Mines—Diamond Mining in the United States". Geology.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ "List Wilderness Areas in Arkansas". University of Montana College of Forestry and Conservation Wilderness Institute, Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. Archived from the original on December 31, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ Arkansas Atlas and Gazetteer. Yarmouth, Maine: DeLorme. 2004. p. 12.

- ^ a b Federal Writers' Project 1987, p. 8.

- ^ Smith 1989, p. 24.

- ^ Smith 1989, p. 25.

- ^ Ecological Regions of North America (PDF) (PDF). 1:10000000. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ Ecoregions of Arkansas (PDF) (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ "Forest Inventory and Analysis". United States Forest Service, Southern Research Station. 2010. Archived from the original (XLS) on December 1, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ Guldin, James M.; Technical Compiler (May 30–31, 1997). "Proceedings of the Symposium on Arkansas Forests: A Conference on the Results of the Recent Forest Survey of Arkansas". Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-41. Asheville, Nc: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. 125 P. 041. United States Forest Service: 74. doi:10.2737/SRS-GTR-41.

- ^ Dale, Edward E. Jr.; Ware, Stewart (April–June 2004). "Distribution of Wetland Tree Species in Relation to a Flooding Gradient and Backwater versus Streamside Location in Arkansas, U.S.A". Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 131 (2): 177–186. doi:10.2307/4126919. JSTOR 4126919.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project 1987, p. 13.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project 1987, p. 12.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project 1987, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project 1987, pp. 13–14.

- ^ "Animals of Arkansas". animalsaroundtheglobe.com. May 2, 2022. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ "Climate in Arkansas". City-data. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ "State Climate Records". State Climate Extremes Committee. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Climatic Data Center. July 23, 2012. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ "Climate—Fayetteville—Arkansas". U.S. Climate Data. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "Climate—Jonesboro—Arkansas". U.S. Climate Data. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2025.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Little Rock, AR". The Weather Channel. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "Climate—Texarkana—Texas". U.S. Climate Data. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "Climate—Monticello—Arkansas". U.S. Climate Data. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "Climate—Fort Smith—Arkansas". U.S. Climate Data. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Darlene (Spring 1954). "Arkansas Post". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 13 (1): 120. doi:10.2307/40037965. JSTOR 40037965.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original (XLS) on July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Estimates of Population Change for Metropolitan Statistical Areas and Rankings". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original (XLS) on July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Arkansas Cities by Population". www.arkansas-demographics.com. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ "Biggest US Cities By Population—Arkansas—2017 Populations". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019". 2010-2019 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. December 30, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Arnold et al. 2002, p. 106.