Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spanish Empire

View on Wikipedia

The Spanish Empire,[b] sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy[c] or the Catholic Monarchy,[d][4][5][6] was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976.[7][8] In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale,[9] controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa, various islands in Asia and Oceania, as well as territory in other parts of Europe.[10] It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, becoming known as "the empire on which the sun never sets".[11] At its greatest extent in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Empire covered 13.7 million square kilometres (5.3 million square miles), making it one of the largest empires in history.[3]

Key Information

Beginning with the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus and continuing for over three centuries, the Spanish Empire would expand across the Caribbean Islands, half of South America, most of Central America and much of North America. In the beginning, Portugal was the only serious threat to Spanish hegemony in the New World. To end the threat of Portuguese expansion, Spain conquered Portugal and the Azores Islands from 1580 to 1582 during the War of the Portuguese Succession, resulting in the establishment of the Iberian Union, a forced union between the two crowns that lasted until 1640 when Portugal regained its independence from Spain. In 1700, Philip V became king of Spain after the death of Charles II, the last Habsburg monarch of Spain, who died without an heir.

The Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation—the first circumnavigation of the Earth—laid the foundation for Spain's Pacific empire and for Spanish control over the East Indies. The influx of gold and silver from the mines in Zacatecas and Guanajuato in Mexico and Potosí in Bolivia enriched the Spanish crown and financed military endeavors and territorial expansion. Spain was largely able to defend its territories in the Americas, with the Dutch, English, and French taking only small Caribbean islands and outposts, using them to engage in contraband trade with the Spanish populace in the Indies. Another crucial element of the empire's expansion was the financial support provided by Genoese bankers, who financed royal expeditions and military campaigns.[12]

The Bourbon monarchy implemented reforms like the Nueva Planta decrees, which centralized power and abolished regional privileges. Economic policies promoted trade with the colonies, enhancing Spanish influence in the Americas. Socially, tensions emerged between the ruling elite and the rising bourgeoisie, as well as divisions between peninsular Spaniards and Creoles in the Americas.[13] These factors ultimately set the stage for the independence movements that began in the early 19th century, leading to the gradual disintegration of Spanish colonial authority.[14] By the mid-1820s, Spain had lost its territories in Mexico, Central America, and South America. By 1900, it had also lost Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippine Islands, and Guam in the Mariana Islands following the Spanish–American War in 1898.[15]

Catholic Monarchs and origins of the empire

[edit]With the marriage of the heirs apparent to their respective thrones Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile created a personal union that most scholars[citation needed] view as the foundation of the Spanish monarchy. The union of the Crowns of Castile and Aragon joined the economic and military power of Iberia under one dynasty, the House of Trastámara. Their dynastic alliance was important for a number of reasons, ruling jointly over a number of kingdoms and other territories, mostly in the western Mediterranean region, under their respective legal and administrative status. They successfully pursued expansion in Iberia in the Christian conquest of the Muslim Emirate of Granada, completed in 1492, for which Valencia-born Pope Alexander VI gave them the title of the Catholic Monarchs. Ferdinand of Aragon was particularly concerned with expansion in France and Italy, as well as conquests in North Africa.[16]

With the Ottoman Turks controlling the choke points of the overland trade from Asia and the Middle East, both Spain and Portugal sought alternative routes. The Kingdom of Portugal had an advantage over the Crown of Castile, having earlier retaken territory from the Muslims. Following Portugal's earlier completion of the reconquest and its establishment of settled boundaries, it began to seek overseas expansion, first to the port of Ceuta (1415) and then by colonizing the Atlantic islands of Madeira (1418) and the Azores (1427–1452); it also began voyages down the west coast of Africa in the fifteenth century.[17] Its rival Castile laid claim to the Canary Islands (1402) and retook territory from the Moors in 1462. The Christian rivals Castile and Portugal came to formal agreements over the division of new territories in the Treaty of Alcaçovas (1479), as well as securing the crown of Castile for Isabella whose accession was challenged militarily by Portugal.

Following the voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492 and first major settlement in the New World in 1493, Portugal and Castile divided the world by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which gave Portugal Africa and Asia, and the Western Hemisphere to Spain.[18] The voyage of Columbus, a Genoese mariner, obtained the support of Isabella of Castile, sailing west in 1492, seeking a route to the Indies. Columbus unexpectedly encountered the New World, populated by peoples he named "Indians". Subsequent voyages and full-scale settlements of Spaniards followed, with gold beginning to flow into Castile's coffers. Managing the expanding empire became an administrative issue. The reign of Ferdinand and Isabella began the professionalization of the apparatus of government in Spain, which led to a demand for men of letters (letrados) who were university graduates (licenciados), of Salamanca, Valladolid, Complutense and Alcalá. These lawyer-bureaucrats staffed the various councils of state, eventually including the Council of the Indies and Casa de Contratación, the two highest bodies in metropolitan Spain for the government of the empire in the New World, as well as royal government in the Indies.

Early expansion: Canary Islands

[edit]

Portugal obtained several papal bulls that acknowledged Portuguese control over the discovered territories, but Castile also obtained from the Pope the safeguard of its rights to the Canary Islands with the bulls Romani Pontifex dated 6 November 1436 and Dominatur Dominus dated 30 April 1437.[19] The conquest of the Canary Islands, inhabited by Guanche people, began in 1402 during the reign of Henry III of Castile, by Norman nobleman Jean de Béthencourt under a feudal agreement with the crown. The conquest was completed with the campaigns of the armies of the Crown of Castile between 1478 and 1496, when the islands of Gran Canaria (1478–1483), La Palma (1492–1493), and Tenerife (1494–1496) were subjugated.[18] By 1504, more than 90 percent of the indigenous Canarians had been killed or enslaved.[20]

Rivalry with Portugal

[edit]The Portuguese tried in vain to keep secret their discovery of the Gold Coast (1471) in the Gulf of Guinea, but the news quickly caused a huge gold rush. Chronicler Pulgar wrote that the fame of the treasures of Guinea "spread around the ports of Andalusia in such way that everybody tried to go there".[21] Worthless trinkets, Moorish textiles, and above all, shells from the Canary and Cape Verde islands were exchanged for gold, slaves, ivory and Guinea pepper.

The War of the Castilian Succession (1475–79) provided the Catholic Monarchs with the opportunity not only to attack the main source of the Portuguese power, but also to take possession of this lucrative commerce. The Crown officially organized this trade with Guinea: every caravel had to secure a government license and to pay a tax on one-fifth of their profits (a receiver of the customs of Guinea was established in Seville in 1475—the ancestor of the future and famous Casa de Contratación).[22]

Castilian fleets fought in the Atlantic Ocean, temporarily occupying the Cape Verde islands (1476), conquering the city of Ceuta in the Tingitan Peninsula in 1476 (but retaken by the Portuguese),[e][f] and even attacked the Azores islands, being defeated at Praia.[g][h] The turning point of the war came in 1478, however, when a Castilian fleet sent by King Ferdinand to conquer Gran Canaria lost men and ships to the Portuguese who expelled the attack,[23] and a large Castilian armada—full of gold—was entirely captured in the decisive Battle of Guinea.[24][i]

The Treaty of Alcáçovas (4 September 1479), while assuring the Castilian throne to the Catholic Monarchs, reflected the Castilian naval and colonial defeat:[25] "War with Castile broke out waged savagely in the Gulf [of Guinea] until the Castilian fleet of thirty-five sail was defeated there in 1478. As a result of this naval victory, at the Treaty of Alcáçovas in 1479 Castile, while retaining her rights in the Canaries, recognized the Portuguese monopoly of fishing and navigation along the whole west African coast and Portugal's rights over the Madeira, Azores and Cape Verde islands [plus the right to conquer the Kingdom of Fez ]."[26] The treaty delimited the spheres of influence of the two countries,[27] establishing the principle of the Mare clausum.[28] It was confirmed in 1481 by the Pope Sixtus IV, in the papal bull Æterni regis (dated on 21 June 1481).[29]

However, this experience would prove to be profitable for future Spanish overseas expansion, because as the Spaniards were excluded from the lands discovered or to be discovered from the Canaries southward[30]—and consequently from the road to India around Africa[31]—they sponsored the voyage of Columbus towards the west (1492) in search of Asia to trade in its spices, encountering the Americas instead.[32] Thus, the limitations imposed by the Alcáçovas treaty were overcome and a new and more balanced division of the world would be reached in the Treaty of Tordesillas between both emerging maritime powers.[33]

New World voyages and Treaty of Tordesillas

[edit]

Seven months before the treaty of Alcaçovas, King John II of Aragon died, and his son Ferdinand II of Aragon, married to Isabella I of Castile, inherited the thrones of the Crown of Aragon. The two became known as the Catholic Monarchs, with their marriage a personal union that created a relationship between the Crown of Aragon and Castile, each with their own administrations, but ruled jointly by the two monarchs.[34]

Ferdinand and Isabella defeated the last Muslim king out of Granada in 1492 after a ten-year war. The Catholic Monarchs then negotiated with Christopher Columbus, a Genoese sailor attempting to reach Cipangu (Japan) by sailing west. Castile was already engaged in a race of exploration with Portugal to reach the Far East by sea when Columbus made his bold proposal to Isabella. In the Capitulations of Santa Fe, dated on 17 April 1492, Christopher Columbus obtained from the Catholic Monarchs his appointment as viceroy and governor in the lands already discovered[35] and that he might discover thenceforth;[36][37] thereby, it was the first document to establish an administrative organization in the Indies.[38] Columbus' discoveries began the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Spain's claim[39] to these lands was solidified by the Inter caetera papal bull dated 4 May 1493, and Dudum siquidem on 26 September 1493.

Since the Portuguese wanted to keep the line of demarcation of Alcaçovas running east and west along a latitude south of Cape Bojador, a compromise was worked out and incorporated in the Treaty of Tordesillas, dated on 7 June 1494, in which the world was split into two dividing Spanish and Portuguese claims. These actions gave Spain exclusive rights to establish colonies in all of the New World from north to south (later with the exception of Brazil, which Portuguese commander Pedro Álvares Cabral encountered in 1500), as well as the easternmost parts of Asia. The Treaty of Tordesillas was confirmed by Pope Julius II in the bull Ea quae pro bono pacis on 24 January 1506.[40]

The Treaty of Tordesillas[41] and the treaty of Cintra (18 September 1509)[42] established the limits of the Kingdom of Fez for Portugal, and the Castilian expansion was allowed outside these limits, beginning with the conquest of Melilla in 1497. Other European powers did not see the treaty between Castile and Portugal as binding on themselves. Francis I of France observed "The sun shines for me as for others and I should very much like to see the clause in Adam's will that excludes me from a share of the world."[43]

First settlements in the Americas

[edit]

Spanish settlement in the New World was based on a pattern of a large, permanent settlements with the entire complex of institutions and material life to replicate Castilian life in a different venue. Columbus's second voyage in 1493 had a large contingent of settlers and goods to accomplish that.[46] On Hispaniola, the city of Santo Domingo was founded in 1496 by Christopher Columbus's brother Bartholomew Columbus and became a stone-built, permanent city. Non-Castilians, such as Catalans and Aragonese, were often prohibited from migrating to the New World.

Following the settlement of Hispaniola, Europeans began searching elsewhere to begin new settlements, since there was little apparent wealth and the numbers of indigenous were declining due to the Taíno genocide. Those from the less prosperous Hispaniola were eager to search for new success in a new settlement. From there Juan Ponce de León conquered Puerto Rico (1508) and Diego Velázquez took Cuba. The Spanish enslaved and deported the entire Lucayan population of the Bahamas by around 1520, leading to their complete extinction.

Columbus encountered the mainland in 1498,[47] and the Catholic Monarchs learned of his discovery in May 1499. The first settlement on the mainland was Santa María la Antigua del Darién in Castilla de Oro (now Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia), settled by Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1510. In 1513, Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama, and led the first European expedition to see the Pacific Ocean from the West coast of the New World. In an action with enduring historical import, Balboa claimed the Pacific Ocean and all the lands adjoining it for the Spanish Crown.[48]

Navarre and struggles for Italy

[edit]

The Catholic Monarchs had developed a strategy of marriages for their children to isolate their rival, France. The Spanish princesses married the heirs of Portugal, England and the House of Habsburg. Following the same strategy, the Catholic Monarchs decided to support the Aragonese house of the Kingdom of Naples against Charles VIII of France in the Italian Wars beginning in 1494. Following Spanish victories at the Battles of Cerignola and Garigliano in 1503, France recognized Ferdinand's sovereignty over Naples through a treaty.[49]

After the death of Queen Isabella in 1504, and her exclusion of Ferdinand from a further role in Castile, Ferdinand married Germaine de Foix in 1505, cementing an alliance with France. Had that couple had a surviving heir, probably the Crown of Aragon would have been split from Castile, which was inherited by Charles, Ferdinand and Isabella's grandson.[50] Ferdinand joined the League of Cambrai against Venice in 1508. In 1511, he became part of the Holy League against France, seeing a chance at taking both Milan—to which he held a dynastic claim—and Navarre. In 1516, France agreed to a truce that left Milan in its control and recognized Spanish control of Upper Navarre, which had effectively been a Spanish protectorate following a series of treaties in 1488, 1491, 1493, and 1495.[51]

Campaigns in North Africa

[edit]With the Christian reconquest completed in the Iberian peninsula, Spain began trying to take territory in Muslim North Africa. It had conquered Melilla in 1497, and further expansionism policy in North Africa was developed during the regency of Ferdinand the Catholic in Castile, stimulated by Cardinal Cisneros. Several towns and outposts in the North African coast were conquered and occupied by Castile between 1505 and 1510: Mers El Kébir, Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera, Oran, Bougie, Tripoli, and Peñón of Algiers. On the Atlantic coast, Spain took possession of the outpost of Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña (1476) with support from the Canary Islands, and it was retained until 1525 with the consent of the Treaty of Cintra (1509).

The Spanish Habsburgs (1516–1700)

[edit]

As a result of the marriage politics of the Catholic Monarchs (in Spanish, Reyes Católicos), their Habsburg grandson Charles inherited the Castilian empire in the Americas and the possessions of the Crown of Aragon in the Mediterranean (including all of southern Italy), lands in Germany, the Low Countries, Franche-Comté, and Austria, starting the rule of the Spanish Habsburgs. The Austrian hereditary Habsburg domains were transferred to Ferdinand, brother of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whereas Spain and the remaining possessions were inherited by Charles's son, Philip II of Spain, at the abdication of the former in 1556.

The Habsburgs pursued several goals:

- Undermining the power of France and containing it in its eastern borders

- Defending Europe against Islam, notably the Ottoman Empire in the Ottoman–Habsburg wars

- Maintaining Habsburg hegemony in the Holy Roman Empire and defending the Roman Catholic Church against the Protestant Reformation

- Spreading (Catholic) Christianity to the unconverted indigenous of the New World and the Philippines

- Exploiting the resources of the Americas (gold, silver, sugar) and trading with Asia (porcelain, spices, silk)

- Excluding other European powers from the possessions it claimed in the New World

"I learnt a proverb here", said a French traveler in 1603: "Everything is dear in Spain except silver".[52] The problems caused by inflation were discussed by scholars at the School of Salamanca and the arbitristas. The natural resource abundance provoked a decline in entrepreneurship as profits from resource extraction are less risky.[53] The wealthy preferred to invest their fortunes in public debt (juros). The Habsburg dynasty spent the Castilian and American riches in wars across Europe on behalf of Habsburg interests, and declared moratoriums (bankruptcies) on their debt payments several times. These burdens led to a number of revolts across the Spanish Habsburg's domains, including their Spanish kingdoms.

Territorial expansion in the Americas

[edit]

During the Habsburg rule, the Spanish Empire significantly expanded its territories in the Americas, beginning with the conquest of the Aztec Empire; these conquests were achieved not by the Spanish army, but by small groups of adventurers—artisans, traders, gentry, and peasants—who operated independently under the crown's encomienda system.[54]

Defying the opposition of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, the governor of Hispaniola, Hernán Cortés organized an expedition of 550 conquistadors and sailed for the coast of Mexico in March 1519. The Castilians defeated a 10,000-strong Chontal Mayan army at Potonchán on 24 March and emerged triumphant against a larger force of 40,000 Mayans three days later. On 2 September, 360 Castilians and 2,300 Totonac Indigenous allies defeated a 20,000-strong Tlaxcalan army. Three days later, a 50,000-strong Otomi-Tlaxcalan force was defeated by Spanish arquebusier and cannon fire, and a Castilian cavalry charge. Thousands of Tlaxcalans joined the invaders against their Aztec rulers. Cortés's forces sacked the city of Cholula, massacring 6,000 inhabitants,[55] and later entered Emperor Moctezuma II's capital, Tenochtitlan, on 8 November. Velázquez sent a force led by Pánfilo de Narváez to punish the insubordinate Cortés for his unauthorized invasion of Mexico, but they were defeated at the Battle of Cempoala on 29 May 1520. Narváez was wounded and captured and 17 of his troops were killed; the rest joined Cortés. Meanwhile, Pedro de Alvarado triggered an Aztec uprising following the massacre in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, during which 400 Aztec nobles and 2,000 onlookers were killed. The Castilians were driven out of the Aztec capital, suffering heavy losses and losing all of their gold and guns during La Noche Triste.

On 8 July 1520, at Otumba, the Castilians and their allies, without artillery or arquebusiers, repelled 100,000 Aztecs armed with obsidian-bladed clubs. In August, 500 Castilians and 40,000 Tlaxcalans conquered the hilltop town of Tepeaca, an Aztec ally. Most of the inhabitants were either branded on the face with the letter "G" (for guerra, the Spanish word for "war") and enslaved by the Spanish, or sacrificed and eaten by the Tlaxcalans.[56] Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan in 1521 with a new invasion force and laid siege to the Aztec capital in May, which was suffering from a smallpox epidemic that killed thousands. The new emperor, Cuauhtémoc, defended Tenochtitlan with 100,000 warriors armed with slings, bows, and obsidian clubs. The first military encounter occurred after an advance along the causeway at Tlacopan by the armies of Alvarado and Cristóbal de Olid. While fighting on the causeway, the Spanish and their allies came under attack from both sides by Aztecs firing arrows from canoes. Thirteen Spanish brigantines sank 300 out of 400 enemy war canoes sent against them. The Aztecs tried to damage the Spanish vessels by hiding spears beneath the shallow water. The attackers breached the city and engaged in fighting with the Aztec defenders in the streets.

The Aztecs defeated the Spanish-Tlaxcalan forces at the Battle of Colhuacatonco on 30 June 1521. Following this Aztec victory, 53 Spanish prisoners were paraded to the tops of Tlatelolco's highest pyramids and publicly sacrificed.[57] In late July, the attackers resumed their assaults, resulting in the massacre of 800 Aztec civilians. By 29 July, the Spanish had reached Tlatelolco's center, raising their new flag atop the city's twin towers. Having exhausted their gunpowder, they attempted a catapult breach but failed. On 3 August, 12,000 more civilians were killed in another city section.[58] Alvarado's destruction of the aqueducts forced the Aztecs to drink from the lake, causing disease and thousands of deaths. Another major assault occurred on 12 August, during which many thousands of non-combatants were massacred in their shelters.[59] The following day, the city fell and Cuauhtémoc was captured. At least 100,000 Aztecs died during the siege, while 100 Spaniards and up to 30,000 of their Indigenous allies were killed or died from disease.

The fall of Tenochtitlan marked the beginning of Spanish colonial rule in Mexico, leading to the establishment of the Viceroyalty of New Spain in 1535. Following the conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521, Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado commenced the conquest of northern Central America in 1523. By 1528, most of the major Maya kingdoms had been subjugated, with only the Petén Basin remaining outside Spanish control. The last independent Maya kingdoms were finally defeated in 1697 during the Spanish conquest of Petén.

In 1532, Francisco Pizarro conquered the Inca Empire by capturing its leader Atahualpa during a surprise attack in Cajamarca that resulted in the massacre of thousands of Incas.[60] This conquest facilitated the establishment of the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1542, allowing Spain to exert control over territories in western South America, comprising present-day Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and parts of Chile and Argentina. In southern Chile, the Spanish faced resistance from the Mapuche people for centuries (Arauco War, lasting from the 1540s into the 1800s).

Reign of Philip II

[edit]Philip II of Spain (r. 1556–98) oversaw the colonization of the Philippines, which began in 1565 with the arrival of Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi, making him ruler of one of the first true globe-spanning empires. His victory in the War of the Portuguese Succession led to the annexation of Portugal in 1580, effectively integrating its overseas empire—encompassing coastal Brazil, the Persian Gulf area, and African and Indian coastal enclaves—into Spain's domain.[61] Philip II also reaffirmed Spanish control over the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Duchy of Milan through the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559. Italy became the core of Spain's power.[j]

Decline

[edit]By the mid-17th century, Spain's global empire burdened its economic, administrative, and military resources. Over the preceding century, Spanish troops had fought in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, suffering heavy casualties.[63] Despite its vast holdings, Spain's military lacked essential modernization and heavily relied on foreign suppliers.[63] Nevertheless, Spain possessed abundant bullion from the Americas, which played a crucial role in both sustaining its military endeavors and meeting the needs of its civilian population. During this period, Spain displayed limited military interest in its overseas colonies. The Criollo elites (colonial-born Spaniards) and mestizo and mulatto militia (of mixed Indigenous-Spanish and African-Spanish descent) provided only minimal protection, often assisted by more influential allies with vested interests in maintaining the balance of power and safeguarding the Spanish Empire from falling into enemy hands.[63]

The Spanish Bourbons (1700–1833)

[edit]

With the 1700 death of the childless Charles II of Spain, the crown of Spain was contested in the War of the Spanish Succession. Under the Treaties of Utrecht (11 April 1713) ending the war, the French prince of the House of Bourbon, Philippe of Anjou, grandchild of Louis XIV of France, became King Philip V of Spain. He retained the Spanish overseas empire in the Americas and the Philippines. The settlement gave spoils to those who had backed a Habsburg for the Spanish monarchy, ceding European territory of the Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Milan, and Sardinia to Austria; Sicily and parts of Milan to the Duchy of Savoy, and Gibraltar and Menorca to the Kingdom of Great Britain. The treaty also granted British merchants the exclusive right to sell slaves in Spanish America for thirty years, the asiento de negros, as well as licensed voyages to ports in Spanish colonial dominions and openings.[64]

Spain's economic and demographic recovery had begun slowly in the last decades of the Habsburg reign, as was evident from the growth of its trading convoys and the much more rapid growth of illicit trade during the period. (This growth was slower than the growth of illicit trade by northern rivals in the empire's markets.) However, this recovery was not then translated into institutional improvement, rather the "proximate solutions to permanent problems."[65] This legacy of neglect was reflected in the early years of Bourbon rule in which the military was ill-advisedly pitched into battle in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–20). Spain was defeated in Italy by an alliance of Britain, France, Savoy, and Austria. Following the war, the new Bourbon monarchy took a much more cautious approach to international relations, relying on a family alliance with Bourbon France, and continuing to follow a program of institutional renewal.

The crown program to enact reforms that promoted administrative control and efficiency in the metropole to the detriment of interests in the colonies, undermined creole elites' loyalty to the crown. When French forces of Napoleon Bonaparte invaded the Iberian peninsula in 1808, Napoleon ousted the Spanish Bourbon monarchy, placing his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne. There was a crisis of legitimacy of crown rule in Spanish America, leading to the Spanish American wars of independence (1808–1826).

Bourbon reforms

[edit]

The Spanish Bourbons' broadest intentions were to reorganize the institutions of empire to better administer it for the benefit of Spain and the crown. It sought to increase revenues and to assert greater crown control, including over the Catholic Church. Centralization of power (beginning with the Nueva Planta decrees against the realms of the Crown of Aragon) was to be for the benefit of the crown and the metropole and for the defense of its empire against foreign incursions.[66] From the viewpoint of Spain, the structures of colonial rule under the Habsburgs were no longer functioning to the benefit of Spain, with much wealth being retained in Spanish America and going to other European powers. The presence of other European powers in the Caribbean, with the English in Barbados (1627), St Kitts (1623–25), and Jamaica (1655); the Dutch in Curaçao, and the French in Saint Domingue (Haiti) (1697), Martinique, and Guadeloupe had broken the integrity of the closed Spanish mercantile system and established thriving sugar colonies.[67][43]

At the beginning of his reign, the first Spanish Bourbon, King Philip V, reorganized the government to strengthen the executive power of the monarch as was done in France, in place of the deliberative, Polysynodial System of Councils.[68]

Philip's government set up a ministry of the Navy and the Indies (1714) and established commercial companies, the Honduras Company (1714), a Caracas company; the Guipuzcoana Company (1728), and the most successful ones, the Havana Company (1740) and the Barcelona Trading Company (1755).

In 1717–18, the structures for governing the Indies, the Consejo de Indias and the Casa de Contratación, which governed investments in the cumbersome Spanish treasure fleets, were transferred from Seville to Cádiz, where foreign merchant houses had easier access to the Indies trade.[69] Cádiz became the one port for all Indies trading (see flota system). Individual sailings at regular intervals were slow to displace the traditional armed convoys, but by the 1760s there were regular ships plying the Atlantic from Cádiz to Havana and Puerto Rico, and at longer intervals to the Río de la Plata, where an additional viceroyalty was created in 1776. The contraband trade that was the lifeblood of the Habsburg empire declined in proportion to registered shipping (a shipping registry having been established in 1735).

Two upheavals registered unease within Spanish America and at the same time demonstrated the renewed resiliency of the reformed system: the Tupac Amaru uprising in Peru in 1780 and the rebellion of the comuneros of New Granada, both in part reactions to tighter, more efficient control.

18th-century economic conditions

[edit]

The 18th century was a century of prosperity for the overseas Spanish Empire as trade within grew steadily, particularly in the second half of the century, under the Bourbon reforms. Spain's victory in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias against a British expedition in the Caribbean port of Cartagena de Indias helped Spain secure its dominance of its possessions in the Americas until the 19th century. But different regions fared differently under Bourbon rule, and even while New Spain was particularly prosperous, it was also marked by steep wealth inequality. Silver production boomed in New Spain during the 18th century, with output more than tripling between the start of the century and the 1750s. The economy and the population both grew, both centered around Mexico City. But while mine owners and the crown benefited from the flourishing silver economy, most of the population in the rural Bajío faced rising land prices, falling wages. Eviction of many from their lands resulted.[70]

With a Bourbon monarchy came a repertory of Bourbon mercantilist ideas based on a centralized state, put into effect in the Americas slowly at first but with increasing momentum during the century. Shipping grew rapidly from the mid-1740s until the Seven Years' War (1756–63), reflecting in part the success of the Bourbons in bringing illicit trade under control. With the loosening of trade controls after the Seven Years' War, shipping trade within the empire once again began to expand, reaching an extraordinary rate of growth in the 1780s.

The end of Cádiz's monopoly of trade with the American colonies brought about very important changes, particularly a rebirth of Spanish manufactures. Most notable of those changes were both the beginning of Catalan participation in the Spanish slave trade, and the rapidly growing textile industry of Catalonia which by the mid-1780s saw the first signs of industrialization. This saw the emergence of a small, politically active commercial class in Barcelona. This isolated pocket of advanced economic development stood in stark contrast to the relative backwardness of most of the country. Most of the improvements were in and around some major coastal cities and the major islands such as Cuba, with its tobacco plantations, and a renewed growth of precious metals mining in South America.

Agricultural productivity remained low despite efforts to introduce new techniques to what was for the most part an uninterested, exploited peasant and laboring groups. Governments were inconsistent in their policies. Though there were substantial improvements by the late 18th century, Spain was still an economic backwater. Under the mercantile trading arrangements it had difficulty in providing the goods being demanded by the strongly growing markets of its empire, and providing adequate outlets for the return trade.

From an opposing point of view according to the "backwardness" mentioned above the naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt traveled extensively throughout the Spanish Americas, exploring and describing it for the first time from a modern scientific point of view between 1799 and 1804. In his work Political essay on the kingdom of New Spain containing researches relative to the geography of Mexico he says that the Amerindians of New Spain were wealthier than any Russian or German peasant in Europe.[71] According to Humboldt, despite the fact that Indian farmers were poor, under Spanish rule they were free and slavery was non-existent, their conditions were much better than any other peasant or farmer in northern Europe.[72]

Humboldt also published a comparative analysis of bread and meat consumption in New Spain compared to other cities in Europe such as Paris. Mexico City consumed 189 pounds of meat per person per year, in comparison to 163 pounds consumed by the inhabitants of Paris, the Mexicans also consumed almost the same amount of bread as any European city, with 363 kilograms of bread per person per year in comparison to the 377 kilograms consumed in Paris. Caracas consumed seven times more meat per person than in Paris. Von Humboldt also said that the average income in that period was four times the European income and also that the cities of New Spain were richer than many European cities.[71]

Contesting with other empires

[edit]

Bourbon institutional reforms under Philip V bore fruit militarily when Spanish forces easily retook Naples and Sicily from the Austrians at the Battle of Bitonto in 1734 during the War of the Polish Succession, and during the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–42) thwarted British efforts to capture the strategic cities of Cartagena de Indias, Santiago de Cuba and St. Augustine, although Spain's invasion of Georgia also ended in failure. The British suffered approximately 20,000 killed or wounded during the war while the Spanish suffered roughly 10,000.[73]

In 1742, the War of Jenkins' Ear merged with the larger War of the Austrian Succession, and King George's War in North America. The British, also occupied with France, were unable to capture Spanish treasure convoys, while Spanish privateers targeted British merchant shipping along the Triangle Trade routes and attacked the coast of North Carolina, levying tribute on the inhabitants. In Europe, Spain had been trying to divest Maria Theresa of the Duchy of Milan in northern Italy since 1741, but faced the opposition of Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia, and warfare in northern Italy remained indecisive throughout the period up to 1746. By the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle, Spain gained (indirectly) Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla in northern Italy.

Spain was defeated during the invasion of Portugal and lost both Havana and Manila to British forces towards the end of the Seven Years' War (1756–63).[74] In response, the Bourbon Reforms allowed for Spain to recover from these losses and Spanish forces recaptured Menorca, West Florida (present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida) and temporarily occupied the Bahamas during the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). However, a Franco-Spanish attempt to capture Gibraltar ended in failure.[citation needed]

During most of the 18th century, Spanish privateers, particularly from Santo Domingo, were the scourge of the Antilles, with Dutch, British, French and Danish vessels as their prizes.[75]

Rival empires in the Pacific Northwest

[edit]

Spain claimed all of North America in the Age of Discovery, but claims were not translated into occupation until a major resource was discovered and Spanish settlement and crown rule put in place. The French had established an empire in northern North America and took some islands in the Caribbean. The English established colonies on the eastern seaboard of North America and in northern North America and some Caribbean islands as well. In the eighteenth century, the Spanish crown realized that its territorial claims needed to be defended, particularly in the wake of its visible weakness during the Seven Years' War when Britain captured the important Spanish ports of Havana and Manila. Another important factor was that the Russian Empire had expanded into North America from the mid-eighteenth century, with fur trading settlements in what is now Alaska and forts as far south as Fort Ross, California. Great Britain was also expanding into areas that Spain claimed as its territory on the Pacific coast. Taking steps to shore up its fragile claims to California, Spain began planning California missions in 1769. Spain also began a series of voyages to the Pacific Northwest, where Russia and Great Britain were encroaching on claimed territory. The Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest, with Alessandro Malaspina and others sailing for Spain, came too late for Spain to assert its sovereignty in the Pacific Northwest.[76]

The Nootka Crisis (1789–1791) nearly brought Spain and Britain to war. It was a dispute over claims in the Pacific Northwest, where neither nation had established permanent settlements. The crisis could have led to war, but without French support Spain capitulated to British terms and negotiations took place with the Nootka Convention. Spain and Great Britain agreed to not establish settlements and allowed free access to Nootka Sound on the west coast of what is now Vancouver Island. Nevertheless, the outcome of the crisis was a humiliation for Spain and a triumph for Britain, as Spain had practically renounced all sovereignty on the North Pacific coast.[77]

In 1806, Baron Nikolai Rezanov attempted to negotiate a treaty between the Russian-American Company and the Viceroyalty of New Spain, but his unexpected death in 1807 ended any treaty hopes. Spain gave up its claims in the West of North America in the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819, ceding its rights there to the United States, allowing the U.S. to purchase Florida, and establishing a boundary between New Spain and the U.S. When the negotiations between the two nations were taking place, Spain's resources were stretched due to the Spanish American wars of independence.[78] Much of the present-day American Southwest later became part of Mexico after its independence from Spain; after the Mexican–American War, Mexico ceded to the U.S. present-day California, Texas, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and parts of Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and Wyoming for $15 million.

Loss of Spanish Louisiana

[edit]

The growth of trade and wealth in the colonies caused increasing political tensions as frustration grew with the improving but still restrictive trade with Spain. Alessandro Malaspina's recommendation to turn the empire into a looser confederation to help improve governance and trade so as to quell the growing political tensions between the élites of the empire's periphery and center was suppressed by a monarchy afraid of losing control. All was to be swept away by the tumult that was to overtake Europe at the turn of the 19th century with the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

The first major territory Spain was to lose in the 19th century was the vast Louisiana Territory, which had few European settlers. It stretched north to Canada and was ceded by France in 1763 under the terms of the Treaty of Fontainebleau. The French, under Napoleon, took back possession as part of the Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800 and sold it to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Napoleon's sale of the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803 caused border disputes between the United States and Spain that, with rebellions in West Florida (1810) and in the remainder of Louisiana at the mouth of the Mississippi River, led to their eventual cession to the United States.

Spanish American Wars of Independence

[edit]

In 1808, Napoleon managed to place the Spanish king under his control, effectively seizing power without facing resistance. This action sparked resistance from the Spanish people, leading to the Peninsular War. This conflict created a power vacuum lasting nearly a decade, followed by civil wars, transitions to a republic, and eventually the establishment of a liberal democracy. Spain lost all the colonial possessions in the first third of the century, except for Cuba, Puerto Rico and, isolated on the far side of the globe, the Philippines, Guam and nearby Pacific islands, as well as Spanish Sahara, parts of Morocco, and Spanish Guinea.

The wars of independence in Spanish America were triggered by another failed British attempt to seize Spanish American territory, this time in the Río de la Plata estuary in 1806. The viceroy retreated hastily to the hills when defeated by a small British force. However, when the Criollos' militias and colonial army decisively defeated the now reinforced British force in 1807, they promptly embarked on the path to securing their own independence, igniting independence movements across the continent. A long period of wars followed in the Americas, and the lack of Spanish troops in the colonies led to war between patriotic rebels and local Royalists. In South America this period of wars led to the independence of Argentina (1810), Gran Colombia (1810), Chile (1810), Paraguay (1811) and Uruguay (1815, but subsequently ruled by Brazil until 1828). José de San Martín campaigned for independence in Chile (1818) and in Peru (1821). Further north, Simón Bolívar led forces that won independence between 1811 and 1826 for the area that became Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia (then Upper Peru). Panama declared independence in 1821 and merged with the Republic of Gran Colombia (from 1821 to 1903). Mexico gained independence in 1821 after more than a decade of struggle, following the War of Independence that began in 1810. Mexico's independence led to the independence of Central American provinces—Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica—by 1823.

As in South America, the Mexican War of Independence was a struggle between Latin Americans fighting for independence and Latin Americans fighting to remain loyal to Spanish rule under King Ferdinand VII. Throughout the eleven years of fighting, Spain sent only 9,685 troops to Mexico.[79] Over the course of nine years, 20,000 Spanish soldiers were sent to reinforce the Spanish American Royalists in northern South America. However, disease and combat claimed the lives of 16,000–17,000 of these soldiers. Even within the Viceroyalty of Peru, the center of Spanish power in South America, the majority of the Royalist army consisted of Americans. After the Battle of Ayacucho in 1824, the captured Royalist army consisted of 1,512 Spanish Americans and only 751 Spaniards. Only 6,000 troops were sent to Peru directly from Spain, although others arrived from neighboring theaters of operation.[80] In 1829, Spain attempted to reconquer Mexico with only 3,000 troops.[81] In contrast, Spain demonstrated a greater military commitment in the Caribbean, sending 30,000 troops to Santo Domingo in 1861 and maintaining a force of 100,000 soldiers in Cuba in 1876.[82]

Last territories in the Americas and the Pacific (1833–1898)

[edit]

In the 1850s and 1860s, Spain engaged in colonial activities around the world, including on the west coast of South America (Chincha Islands War), in Vietnam (Cochinchina campaign), and in Mexico. In 1861, Spain annexed Santo Domingo, which had been independent from Spain since 1821[83][84] and from Haiti since 1844.[85][86] This led to a guerrilla war in 1863. By the time Spain withdrew from Santo Domingo in 1865, it had spent over 33 million pesos fighting insurgents, with 10,888 Spanish soldiers killed or wounded in action and 18,000 dead from all causes.[87] Dominicans who had sided with Spain relocated to Cuba, where they later played a key role in helping Cuban rebels defeat Spanish detachments and gain control of much of eastern Cuba during the Ten Years' War.[82]

In Cuba, the First War for Independence was fought from 1868 to 1878, resulting in between 100,000 and 150,000 Cuban deaths.[88] The Second War for Independence occurred between 1895 and 1898, during which approximately 300,000 Cubans died, with around 200,000 civilian deaths attributed to disease and famine caused by Spanish concentration camps.[89] Two contemporary sources estimated that by December 1895, the rebel army had lost between 29,850 and 42,800 men, and many Cuban generals were killed in combat.[89]

American sympathy for Cuban revolutionaries grew due to reports of atrocities and the sinking of USS Maine. On 25 April 1898, the U.S. declared war on Spain, marking the start of the Spanish-American War. The destruction of Spain's Pacific and Caribbean fleets at Manila Bay and Santiago de Cuba severed supply lines, leading to the surrender of Spanish garrisons in the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, the last two of which were the remaining territories of the empire in the Americas. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris (1898), which ceded Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the U.S. and sold the Philippines for US$20 million.[90] The following year, Spain then sold its remaining Pacific Ocean possessions to Germany in the German–Spanish Treaty, retaining only its African territories. On 2 June 1899, the second expeditionary battalion Cazadores of Philippines, the last Spanish garrison in the Philippines, which had been besieged in Baler, Aurora at war's end, was pulled out, effectively ending around 300 years of Spanish hegemony in the archipelago.[91]

Territories in Africa (1885–1976)

[edit]

By the end of the 17th century, only Melilla, Alhucemas, Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera (which had been taken again in 1564), and Ceuta (part of the Portuguese Empire since 1415, chose to retain their links to Spain once the Iberian Union ended. The formal allegiance of Ceuta to Spain was recognized by the Treaty of Lisbon in 1668), and Oran and Mers El Kébir remained Spanish territories in Africa. The latter cities were lost in 1708, reconquered in 1732 and sold by Charles IV in 1792.

In 1778, Fernando Pó (now Bioko), adjacent islets, and commercial rights to the mainland between the Niger and Ogooué rivers were ceded to Spain by the Portuguese in exchange for territory in South America (Treaty of El Pardo). In the 19th century, some Spanish explorers and missionaries would cross this zone, among them Manuel Iradier. In 1848, Spanish troops occupied the uninhabited Chafarinas Islands, anticipating a French move on the rocks located off the North-African coast.

In 1860, after the Tetuan War, Morocco paid Spain 100 million pesetas as war reparations and ceded Sidi Ifni to Spain as a part of the Treaty of Tangiers, on the basis of the old outpost of Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña, thought to be Sidi Ifni. The following decades of Franco-Spanish collaboration resulted in the establishment and extension of Spanish protectorates south of the city, and Spanish influence obtained international recognition in the Berlin Conference of 1884: Spain administered Sidi Ifni and Spanish Sahara jointly. Spain claimed a protectorate over the coast of Guinea from Cape Bojador to Cap Blanc, too, and even try to press a claim over the Adrar and Tiris regions in Mauritania. Río Muni became a protectorate in 1885 and a colony in 1900. Conflicting claims to the Guinea mainland were settled in 1900 by the Treaty of Paris, because of which Spain was left with a mere 26,000 km2 out of the 300,000 stretching east to the Ubangi River which they initially claimed.[92]

Following a brief war in 1893, Morocco paid war reparations of 20 million pesetas and Spain expanded its influence south from Melilla. In 1912, Morocco was divided between the French and Spanish. The Riffians rebelled, led by Abdelkrim, a former officer for the Spanish administration. The Battle of Annual (1921) during the Rif War was a major military defeat suffered by the Spanish army against Moroccan insurgents. A leading Spanish politician emphatically declared: "We are at the most acute period of Spanish decadence".[93] After the disaster of Annual, Spain began using German chemical weapons against the Moroccans. In September 1925, the Alhucemas landing by the Spanish Army and Navy with a small collaboration of an allied French contingent put an end to the Rif War. It is considered the first successful amphibious landing in history supported by seaborne air power and tanks.[94]

In 1923, Tangier was declared an international city under French, Spanish, British, and later Italian joint administration. In 1926, Bioko and Rio Muni were united as the colony of Spanish Guinea, a status that would last until 1959. In 1931, following the fall of the monarchy, the African colonies became part of the Second Spanish Republic. In 1934, during the government of Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, Spanish troops led by General Osvaldo Capaz landed in Sidi Ifni and carried out the occupation of the territory, ceded de jure by Morocco in 1860. Two years later, Francisco Franco, a general of the Army of Africa, rebelled against the republican government and started the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). During the Second World War the Vichy French presence in Tangier was overcome by that of Francoist Spain.

Spain lacked the wealth and the interest to develop an extensive economic infrastructure in its African colonies during the first half of the 20th century. However, through a paternalistic system, particularly on Bioko Island, Spain developed large cocoa plantations for which thousands of Nigerian workers were imported as laborers.

In 1956, when French Morocco became independent, Spain surrendered Spanish Morocco to the new nation, but retained control of Sidi Ifni, the Tarfaya region and Spanish Sahara. Moroccan Sultan (later King) Mohammed V was interested in these territories and unsuccessfully invaded Spanish Sahara in 1957, in the Ifni War, or in Spain, the Forgotten War (la Guerra Olvidada). In 1958, Spain ceded Tarfaya to Mohammed V and joined the previously separate districts of Saguia el-Hamra (in the north) and Río de Oro (in the south) to form the province of Spanish Sahara.

In 1959, the Spanish territory on the Gulf of Guinea was established with a status similar to the provinces of metropolitan Spain. As the Spanish Equatorial Region, it was ruled by a governor general exercising military and civilian powers. The first local elections were held in 1959, and the first Equatoguinean representatives were seated in the Spanish parliament. Under the Basic Law of December 1963, limited autonomy was authorized under a joint legislative body for the territory's two provinces. The name of the country was changed to Equatorial Guinea. In March 1968, under pressure from Equatoguinean nationalists and the United Nations, Spain announced that it would grant the country independence.

In 1969, under international pressure, Spain returned Sidi Ifni to Morocco. Spanish control of Spanish Sahara endured until the 1975 Green March prompted a withdrawal, under Moroccan military pressure. The future of this former Spanish colony remains uncertain.

The Canary Islands and Spanish cities in the African mainland are considered an equal part of Spain and the European Union but have a different tax system.

Morocco still claims Ceuta, Melilla, and plazas de soberanía even though they are internationally recognized as administrative divisions of Spain. Isla Perejil was occupied on 11 July 2002 by Moroccan Gendarmerie and troops, who were evicted by Spanish naval forces in a bloodless operation.

Imperial economic policy

[edit]

The Spanish Empire benefited from favorable factor endowments from its overseas possessions with their large, exploitable indigenous populations and rich mining areas.[95] Thus the crown attempted to create and maintain a classic closed mercantile system, warding off competitors and keeping wealth within the empire, specifically within the Crown of Castile. While in theory the Habsburgs were committed to maintaining a state monopoly, the reality was that the empire was a porous economic realm with widespread smuggling. In the 16th and 17th centuries under the Habsburgs, Spain's economic conditions gradually declined, especially in regards to the industrial development of its French, Dutch, and English rivals. Many of the goods being exported to the Empire originated from manufacturers in northwest Europe rather than in Spain. Illicit commercial activities became a part of the Empire's administrative structure. Supported by large flows of silver from the Americas, trade prohibited by Spanish mercantilist restrictions flourished as it provided a source of income to both crown officials and private merchants.[96] The local administrative structure in Buenos Aires, for example, was established through its oversight of both legal and illegal commerce.[97] The crown's pursuit of wars to maintain and expand territory, defend the Catholic faith, stamp out Protestantism, and beat back the Ottoman Turkish strength outstripped its ability to pay for it all, despite the huge production of silver in Peru and New Spain. Most of that flow paid mercenary soldiers in the European religious wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and paid foreign merchants for the consumer goods manufactured in northern Europe. Paradoxically, the wealth of the Indies impoverished Spain and enriched northern Europe, a course the Bourbon monarchs would later attempt to reverse in the eighteenth century.[98]

This was well acknowledged in Spain, with writers on political economy, the arbitristas, sending the crown lengthy analyses in the form of "memorials, of the perceived problems and with proposed solutions."[99][100] According to these thinkers, "Royal expenditure must be regulated, the sale of office halted, the growth of the church checked. The tax system must be overhauled, special concessions be made to agricultural laborers, rivers be made navigable and dry lands irrigated. In this way alone could Castile's productivity increase, its commerce restored, and its humiliating dependence on foreigners, on the Dutch and the Genoese, be brought to an end."[101]

Since the early days of the Caribbean and conquest era, the crown attempted to control trade between Spain and the Indies with restrictive policies enforced by the House of Trade (est. 1503) in Seville. Shipping was through particular ports in Castile: Seville, and subsequently Cádiz, Spanish America: Veracruz, Acapulco, Havana, Cartagena de Indias, and Callao/Lima, and the Philippines: Manila. There were very few Spanish settlers in the Indies in the very early period and Spain could supply sufficient goods to them. But as the Aztec and Inca empires were conquered in the early sixteenth century, and large deposits of silver found in both Mexico and Peru, Spanish immigration increased and the demand for goods rose far beyond Spain's ability to supply it. Since Spain had little capital to invest in the expanding trade and no significant commercial group, bankers and commercial houses in Genoa, Germany, the Netherlands, France, and England supplied both investment capital and goods in a supposedly closed system. Even in the sixteenth century, Spain recognized that the idealized closed system did not function in reality. Since the crown did not alter its restrictive structure or advocate fiscal prudence, despite the pleas of the arbitristas, the Indies trade remained nominally in the hands of Spain, but in fact enriched the other European countries.

The crown established the system of treasure fleets (Spanish: flota) to protect the conveyance of silver to Seville (later Cádiz). Produced in other European countries, Sevillian merchants conveyed consumer goods that were registered and taxed by the House of Trade, and then sent to the Indies. Other European commercial interests came to dominate supply, with Spanish merchant houses and their guilds (consulados) in both Spain and the Indies acting as mere middlemen, reaping a slice of the profits. However, those profits did not promote a manufacturing sector in Spain's economic development, and its economy continued to be based in agriculture. The wealth of the Indies led to prosperity in northern Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and England, which were both Protestant. As Spain's power weakened in the seventeenth century, England, the Netherlands, and the French took advantage overseas by seizing islands in the Caribbean, which became bases for a burgeoning contraband trade in Spanish America. Crown officials, who were supposed to suppress contraband trade, were quite often in cahoots with the foreigners, since it was a source of personal enrichment. In Spain, the crown itself participated in collusion with foreign merchant houses, since they paid fines "meant to establish a compensation to the state for losses through fraud." It became a calculated risk for merchant houses doing business, and for the crown it gained income that would have otherwise been lost. Foreign merchants were part of the supposed monopoly system of trade. The transfer of the House of Trade from Seville to Cádiz meant foreign merchant houses had even easier access to the Spanish trade.[103]

The Spanish imperial economy's major global impact was silver mining. The mines in Peru and Mexico were in the hands of a few elite mining entrepreneurs with access to capital and a stomach for the risk that mining entailed. They operated under a system of royal licensing, since the crown held the rights to subsoil wealth. Mining entrepreneurs assumed all the risk of the enterprise, while the crown gained a 20% slice of the profits, the royal fifth ("quinto real"). Further adding to the crown's revenues in mining was that it held a monopoly on the mercury supply, used for separating pure silver from silver ore in the patio process. The crown kept the price high, thereby depressing the volume of silver production.[104] Protecting its flow from Mexico and Peru as it transited to ports for shipment to Spain resulted early on in a convoy system (the flota) sailing twice a year. Its success can be judged by the fact that the silver fleet was captured only once, in 1628 by Dutch privateer Piet Hein. That loss resulted in the bankruptcy of the Spanish crown and an extended period of economic depression in Spain.[105]

One practice the Spanish used to gather workers for the mines was called repartimiento. This was a rotational forced labor system where indigenous pueblos were obligated to send laborers to work in Spanish mines and plantations for a set number of days out of the year. Repartimiento was not implemented to replace slave labor, but instead existed alongside free wage labor, slavery, and indentured labor. It was, however, a way for the Spanish to procure cheap labor, thus boosting the mining-driven economy.

The men who worked as repartimiento laborers were not always resistant to the practice. Some were drawn to the labor as a way to supplement the wages they earned cultivating fields so as to support their families and, of course, pay tributes. At first, a Spaniard could get repartimiento laborers to work for them with permission from a crown official, such as a viceroy, only on the basis that this labor was absolutely necessary to provide the country with important resources. This condition became laxer as the years went on, and various enterprises had repartimiento laborers who would work in dangerous conditions for long hours and low wages.[106]

During the Bourbon era, economic reforms sought to reverse the pattern that left Spain impoverished with no manufacturing sector and its colonies' need for manufactured goods supplied by other nations. It attempted to establish a closed trading system, but it was hampered by the terms of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. The treaty ending the War of the Spanish Succession, with a victory for the Bourbon French candidate for the throne, had a provision for British merchants to legally sell slaves with a license (Asiento de Negros) slaves to Spanish America. The provision undermined the possibility of a revamped Spanish monopoly system. The merchants also used the opportunity to engage in contraband trade of their manufactured goods. Crown policy sought to make legal trade more appealing than contraband by instituting free commerce (comercio libre) in 1778, whereby Spanish American ports could trade with each other, and they could trade with any port in Spain. It was aimed at revamping a closed Spanish system and outflanking the increasingly powerful British. Silver production revived in the eighteenth century, with production far surpassing the earlier output. The crown reduced the taxes on mercury, meaning that a greater volume of pure silver could be refined. Silver mining absorbed most of the available capital in Mexico and Peru, and the crown emphasized the production of precious metals, which were sent to Spain. There was some economic development in the Indies to supply food, but a diversified economy did not emerge.[104] The economic reforms of the Bourbon era both shaped and were themselves impacted by geopolitical developments in Europe. The Bourbon Reforms arose out of the War of the Spanish Succession. In turn, the crown's attempt to tighten its control over its colonial markets in the Americas led to further conflict with other European powers who were vying for access to them. After a sparking a series of skirmishes throughout the 1700s over its stricter policies, Spain's reformed trade system led to war with Britain in 1796.[107] In the Americas, meanwhile, economic policies enacted under the Bourbons had different impacts in different regions. On one hand, silver production in New Spain greatly increased and led to economic growth. But much of the profits of the revitalized mining sector went to mining elites and state officials, while in rural areas of New Spain conditions for rural workers deteriorated, contributing to social unrest that would impact subsequent revolts.[70]

Scientific investigations and expeditions

[edit]

The Spanish American Enlightenment produced a huge body of information on Spain's overseas empire via scientific expeditions. The most famous traveler in Spanish America was Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt, whose travel writings, especially Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain and scientific observations remain important sources for the history of Spanish America. Humboldt's expedition was authorized by the crown, but was self-funded from his personal fortune. The Bourbon crown promoted state-funded scientific work prior to the famous Humboldt expedition. Eighteenth-century clerics contributed to the expansion of scientific knowledge.[108] These include José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez,[109] and José Celestino Mutis.

The Spanish crown funded a number of important scientific expeditions: Botanical Expedition to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1777–78); Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada (1783–1816);[110] the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain (1787–1803);[111] which scholars are now examining afresh.[112] Although the crown funded a number of Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest to bolster claims to territory, lengthy transatlantic and transpacific Malaspina-Bustamante Expedition was for scientific purposes. The crown also funded the Balmis Expedition in 1804 to vaccinate colonial populations against smallpox.

Much of the research done in the eighteenth century was never published or otherwise disseminated, in part due to budgetary constraints on the crown. Starting in the late twentieth century, research on the history of science in Spain and the Spanish empire has blossomed, with primary sources being published in scholarly editions or reissued, as well the publication of a considerable number of important scholarly studies.[113]

Legacy

[edit]Although the Spanish Empire declined from its apogee in the late seventeenth century, it remained a wonder for other Europeans for its sheer geographical span. Writing in 1738, English author Samuel Johnson questioned, "Has heaven reserved, in pity to the poor,/No pathless waste or undiscovered shore,/No secret island in the boundless main,/No peaceful desert yet unclaimed by Spain?"[114]

The Spanish Empire left a huge linguistic, religious, political, cultural, and urban architectural legacy in the Western Hemisphere. With over 470 million native speakers today, Spanish is the second most spoken native language in the world, as result of the introduction of the language of Castile—Castilian, "Castellano" —from Iberia to Spanish America, later expanded by the governments of successor independent republics. In the Philippines, the Spanish–American War (1898) brought the islands under U.S. jurisdiction, with English being imposed in schools and Spanish becoming a secondary official language. Many indigenous languages throughout the empire were often lost either as indigenous populations were decimated by war and disease, or as indigenous people mixed with colonists, and the Spanish language was taught and spread over time.[115]

An important cultural legacy of the Spanish empire overseas is Roman Catholicism, which remains the main religious faith in Spanish America and the Philippines. Christian evangelization of indigenous peoples was a key responsibility of the crown and a justification for its imperial expansion. Although indigenous were considered neophytes and insufficiently mature in their faith for indigenous men to be ordained to the priesthood, the indigenous were part of the Catholic community of faith. Catholic orthodoxy was enforced by the Inquisition, particularly targeting crypto-Jews and Protestants. Not until after their independence in the nineteenth century did Spanish American republics allow religious toleration of other faiths. Observances of Catholic holidays often have strong regional expressions and remain important in many parts of Spanish America. Observances include Day of the Dead, Carnival, Holy Week, Corpus Christi, Epiphany, and national saints' days, such as the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico.

Politically, the colonial era has strongly influenced modern Spanish America. The territorial divisions of the empire in Spanish America became the basis for boundaries between new republics after independence and for state divisions within countries. It is often argued that the rise of caudillismo during and after Latin American independence movements created a legacy of authoritarianism in the region.[116] There was no significant development of representative institutions during the colonial era, and the executive power was often made stronger than the legislative power during the national period as a result.

This has led to a popular misconception that the colonial legacy has caused the region to have an extremely oppressed proletariat. Revolts and riots are often seen as evidence of this supposed extreme oppression. However, the culture of revolting against an unpopular government is not simply a confirmation of widespread authoritarianism. The colonial legacy did leave a political culture of revolt, but not always as a desperate last act. The civil unrest of the region is seen by some as a form of political involvement. While the political context of the political revolutions in Spanish America is understood to be one in which liberal elites competed to form new national political structures, so too were those elites responding to mass lower-class political mobilization and participation.[117]

Hundreds of towns and cities in the Americas were founded during the Spanish rule, with the colonial centers and buildings of many of them now designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites attracting tourists. The tangible heritage includes universities, forts, cities, cathedrals, schools, hospitals, missions, government buildings and colonial residences, many of which still stand today. A number of present-day roads, canals, ports or bridges sit where Spanish engineers built them centuries ago. The oldest universities in the Americas were founded by Spanish scholars and Catholic missionaries. The Spanish Empire also left a vast cultural and linguistic legacy. The cultural legacy is also present in the music, cuisine, and fashion, some of which have been granted the status of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

The long colonial period in Spanish America resulted in a mixing of indigenous peoples, Europeans, and Africans that were classified by race and hierarchically ranked, which created a markedly different society than the European colonies of North America. In concert with the Portuguese, the Spanish Empire laid the foundations of a truly global trade by opening up the great trans-oceanic trade routes and the exploration of unknown territories and oceans for the western knowledge. The Spanish dollar became the world's first global currency.[118]

One of the features of this trade was the exchange of a great array of domesticated plants and animals between the Old World and the New in the Columbian Exchange. Some cultivars that were introduced to the Americas included grapes, wheat, barley, apples and citrous fruits; animals that were introduced to the New World were horses, donkeys, cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and chickens. The Old World received from the Americas such things as maize, potatoes, chili peppers, tomatoes, tobacco, beans, squash, cacao (chocolate), vanilla, avocados, pineapples, chewing gum, rubber, peanuts, cashews, Brazil nuts, pecans, blueberries, strawberries, quinoa, amaranth, chia, agave and others. The result of these exchanges was to significantly improve the agricultural potential of not only in the Americas, but also that of Europe and Asia. Diseases brought by Europeans and Africans, such as smallpox, measles, typhus, and others, devastated almost all indigenous populations that had no immunity.

There were also cultural influences, which can be seen in everything from architecture to food, music, art and law, from southern Argentina and Chile to the United States of America together with the Philippines. The complex origins and contacts of different peoples resulted in cultural influences coming together in the varied forms evident today in the former colonial areas.

Gallery

[edit]-

A photo of Cathedral of Mexico City. It is one of the largest cathedrals in Americas, built on the ruins of the Aztec main square.

-

The clock of Comayagua Cathedral's bell tower in Honduras is one of the oldest clocks in Americas and the oldest still working in the world.[119] It was brought from the Alhambra Arab palace to the Spanish colonies during the 17th century.

-

Templo del Carmen in San Luis Potosí city, Mexico in January 2014. It is one of the largest churches in Americas.

-

Roof tiles are a common Hispanic American architectural element because Spanish colonization. Hospital Escuela Eva Perón in Granadero Baigorria, Santa Fe, Argentina.

-

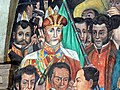

Detail of a Mural by Diego Rivera at the National Palace of Mexico showing the ethnic differences between Agustín de Iturbide, a criollo, and the multiracial Mexican court

See also

[edit]- Spanish Colonial architecture

- Society in the Spanish Colonial Americas

- Cartography of Latin America

- Colonialism

- Creole nationalism

- Governor-General of the Philippines

- Historiography of Colonial Spanish America

- History of Spain

- History of the Americas

- Black legend (Spain)

- List of countries that gained independence from Spain

- List of oldest buildings in the Americas

- Spain

- Spanish Viceroys of Aragon

- Spanish Viceroys of Catalonia

- Spanish Viceroys of Naples

- Spanish Viceroys of Navarre

- Spanish Viceroys of Sardinia

- Spanish Viceroys of Sicily

- Spanish Viceroys of Valencia

- Viceroys of New Granada

- Viceroys of New Spain

- Viceroys of Peru

- Viceroys of Río de la Plata

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Catholic Church was the State religion of the Spanish Empire, but the following religions were also present in the empire: Islam (Sunni Islam (Hanafi and Maliki [the latter until 1609] schools), Shia Islam, Crypto-Islam), Aztec religions, Inca religions, Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, Animism and Judaism (Crypto-Judaism).

- ^ Spanish: Imperio español

- ^ Spanish: Monarquía Hispánica

- ^ Spanish: Monarquía Católica

- ^ ... In August, the Duke besieged Ceuta [The city was simultaneously besieged by the moors and a Castilian army led by the Duke of Medina Sidónia] and took the whole city except the citadel, but with the arrival of Afonso V in the same fleet which led him to France, he preferred to leave the square. As a consequence, this was the end of the attempted settlement of Gibraltar by converts from Judaism ... which D. Enrique de Guzmán had allowed in 1474, since he blamed them for the disaster. See Ladero Quesada, Miguel Ángel (2000), "Portugueses en la frontera de Granada" in En la España Medieval, vol. 23 (in Spanish), p. 98, ISSN 0214-3038.

- ^ A dominated Ceuta by the Castilians would certainly have forced a share of the right to conquer the Kingdom of Fez (Morocco) between Portugal and Castile instead of the Portuguese monopoly recognized by the treaty of Alcáçovas. See Coca Castañer (2004), "El papel de Granada en las relaciones castellano-portuguesas (1369–1492)", in Espacio, tiempo y forma (in Spanish), Serie III, Historia Medieval, tome 17, p. 350: ... In that summer, D. Enrique de Guzmán crossed the Strait with five thousand men to conquer Ceuta, managing to occupy part of the urban area on the first thrust, but knowing that the Portuguese King was coming with reinforcements to the besieged [Portuguese], he decided to withdraw ...

- ^ A Castilian fleet attacked the Praia's Bay in Terceira Island but the landing forces were decimated by a Portuguese counter-attack because the rowers panicked and fled with the boats. See chronicler Frutuoso, Gaspar (1963)- Saudades da Terra (in Portuguese), Edição do Instituto Cultural de Ponta Delgada, volume 6, chapter I, p. 10. See also Cordeiro, António (1717)- Historia Insulana (in Portuguese), Book VI, Chapter VI, p. 257

- ^ This attack happened during the Castilian war of Succession. See Leite, José Guilherme Reis- Inventário do Património Imóvel dos Açores Breve esboço sobre a História da Praia (in Portuguese).

- ^ This was a decisive battle because after it, in spite of the Catholic Monarchs' attempts, they were unable to send new fleets to Guinea, Canary or to any part of the Portuguese empire until the end of the war. The Perfect Prince sent an order to drown any Castilian crew captured in Guinea waters. Even the Castilian navies which left to Guinea before the signature of the peace treaty had to pay the tax ("quinto") to the Portuguese crown when returned to Castile after the peace treaty. Isabella had to ask permission to Afonso V so that this tax could be paid in Castilian harbors. Naturally all this caused a grudge against the Catholic Monarchs in Andalusia.

- ^ Italian financiers from Milan and Genoa managed the crown's credit, while Italian generals, soldiers, and ships played a crucial role in supporting Spain's army and naval power. The Duchy of Milan served as Spain's main military base in Europe, blocking French expansion and facilitating troop movements via the Spanish Road. Milan's armaments industry provided war materials, and the Kingdom of Naples contributed recruits and taxes, which many Italians saw as exploitation for Spain's imperial ambitions, although Philip II insisted that the monarchy did not intend to exploit them.[62]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Monarchy nominally restored in 1947

- ^ Government proclaimed in 1936

- ^ a b Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia" (PDF). International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 492–502. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Fernández Álvarez, Manuel (1979). España y los españoles en los tiempos modernos (in Spanish). University of Salamanca. p. 128.

- ^ Schneider, Reinhold, 'El Rey de Dios', Belacqva (2002)

- ^ Hugh Thomas, 'World Without End: The Global Empire of Philip II', Penguin; first edition (2015)

- ^ Wright, Edmund, ed. (2015). A Dictionary of World History (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192807007.001.0001. ISBN 978-0191726927.

- ^ Echávez-Solano, Nelsy; Dworkin y Méndez, Kenya C., eds. (2007). Spanish and Empire. Nashville, Tenn.: Vanderbilt University Press. pp. xi–xvi. doi:10.2307/j.ctv16755vb.3. ISBN 978-0826515667. S2CID 242814420.