Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Greek cuisine

View on Wikipedia

Greek cuisine is the cuisine of Greece and the Greek diaspora.[1] In common with many other cuisines of the Mediterranean, it is founded on the triad of wheat, olive oil, and wine.[2] It uses vegetables, olive oil, grains, fish, and meat, including pork, poultry, veal and beef, lamb, rabbit, and goat. Other important ingredients include[3] pasta (such as hilopites),[4] cheeses,[5] herbs, lemon juice,[6] olives and olive oil,[7] and yogurt. Bread made of wheat is ubiquitous; other grains, notably barley, are also used, especially for paximathia. Common dessert ingredients include nuts, honey, fruits, sesame, and filo pastries. It continues traditions from Ancient Greek and Byzantine cuisine,[8] while incorporating Asian, Turkish, Balkan, and Italian influences.[9]

History

[edit]

Greek cuisine is part of the culture of Greece and is recorded in images and texts from ancient times.[10][11][12] Its influence spread to ancient Rome and then throughout Europe and beyond.[13]

Ancient Greek cuisine was characterized by its frugality and was founded on the "Mediterranean triad": wheat, olive oil, and wine, with meat being rarely eaten and fish being more common.[14] This trend in Greek diet continued in Cyprus and changed only fairly recently when technological progress has made meat more available.[15] Wine and olive oil have always been a central part of it and the spread of grapes and olive trees in the Mediterranean and further afield is correlated with Greek colonization.[16][17]

The Spartan diet was also marked by its frugality. A notorious staple of the Spartan diet was melas zomos (black soup), made by boiling the pigs' legs, blood of pigs, olive oil, bay leaf, chopped onion, salt, water, and vinegar as an emulsifier to keep the blood from coagulation during the cooking process. The army of Sparta mainly ate this as part of their subsistence diet. This dish was noted by the Spartans' Greek contemporaries, particularly Athenians and Corinthians, as proof of the Spartans' different way of living.

Byzantine cuisine was similar to ancient cuisine, with the addition of new ingredients, such as caviar, nutmeg and basil. Lemons, prominent in Greek cuisine and introduced in the second century, were used medicinally before being incorporated into the diet. Fish continued to be an integral part of the diet for coastal dwellers. Culinary advice was influenced by the theory of humors, first put forth by the ancient Greek doctor Claudius Aelius Galenus.[18] Byzantine cuisine benefited from Constantinople's position as a global hub of the spice trade.[19]

Overview

[edit]

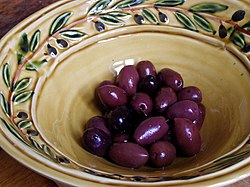

The most characteristic and ancient element of Greek cuisine is olive oil, which is used in most dishes. It is produced from the olive trees prominent throughout the region, and adds to the distinctive taste of Greek food. The olives themselves are also widely eaten. The basic grain in Greece is wheat, though barley is also grown. Important vegetables include tomatoes, aubergine (eggplant), potato, green beans, okra, green peppers (capsicum), and onions. Honey in Greece is mainly honey from the nectar of fruit trees and citrus trees: lemon, orange, bigarade (bitter orange) trees, thyme honey, and pine honey. Mastic, an aromatic, ivory-coloured plant resin, is grown on the Aegean island of Chios.

Greek cuisine uses some flavorings more often than other Mediterranean cuisines do, namely oregano, mint, garlic, onion, dill, cumin, and bay laurel leaves. Other common herbs and spices include basil, thyme and fennel seed. Parsley is also used as a garnish on some dishes. Many Greek recipes, especially in the northern parts of the country,[20][21][22] use "sweet" spices in combination with meat, such as cinnamon, allspice and cloves in stews.[23][24][25]

The climate and terrain has tended to favour the breeding of goats and sheep over cattle, and thus beef dishes are uncommon. Fish dishes are common in coastal regions and on the islands. A great variety of cheese types are used in Greek cuisine, including Feta, Kasseri, Kefalotyri, Graviera, Anthotyros, Manouri, Metsovone, Ladotyri (cheese with olive oil), Kalathaki (a specialty from the island of Limnos), Katiki Domokou (creamy cheese, suitable for spreads), Mizithra and many more.[26]

Dining out is common in Greece. The taverna and estiatorio are widespread, serving home cooking at affordable prices to both locals and tourists.[27][28][29][30] Locals largely eat Greek cuisine.[31][32][33][34][35]

Common street foods include souvlaki, gyros, various pitas and roast corn.[36]

Fast food became popular in the 1970s, with some chains, such as Goody's and McDonald's serving international food like hamburgers,[37] and others serving Greek foods such as souvlaki, gyros, tiropita, and spanakopita.

Since 2013, Greece for its Mediterranean diet has been added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[38]

Origins

[edit]Many dishes can be traced back to ancient Greece: lentil soup, fasolada (though the modern version is made with white beans and tomatoes, both New World plants), tiganites, retsina (white or rosé wine flavored with pine resin) and pasteli (baked sesame-honey bar); some to the Hellenistic and Roman periods: loukaniko (dried pork sausage); and Byzantium: feta cheese, avgotaraho (cured fish roe), moustalevria and paximadi (traditional hard bread baked from wheat, barley and rye).[39] There are also many ancient and Byzantine dishes which are no longer consumed: porridge (hilós in Greek) as the main staple, fish sauce (garos), and salt water mixed into wine.[40][41][42]

Some dishes are borrowed from Italian and adapted to Greek tastes: pastitsio (pasticcio), pastitsada (pasticciata), stifado (stufato), salami, macaronia, mandolato, and more.[43]

Some Greek dishes are inherited from Ottoman cuisine, which combined influences from Persian, Levantine, Arabian, Turkish and Byzantine cuisines: meze, kadaifi, halva, and loukoumi.

In the 20th century, French cuisine had a major influence on Greek cooking,[44][45][46] largely due to the French-trained chef Nikolaos Tselementes, who created the modern Greek pastitsio; he also created the modern Greek version of moussaka by combining an existing eggplant dish with a French-style gratin topping. Greek chef Zisis Kerameas[47][48] has recognized for his contribution to Greek cuisine and as culinary arts teacher (1970–2000) at public vocational tourism professions schools.

Regions

[edit]Distinct from the mainstream regional cuisines are:[49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57]

- Cuisine of the Aegean islands (including Kykladítiki from Kyklades, Rhodítiki from Rhodes and other Dodecanese islands, and the Cuisine of Lesbos island).

- Cuisine of Argolis, Cuisine of Patras, Arcadian and Maniot cuisines, parts of the Cuisine of Peloponnesean.[58]

- Cuisine of the Ionian islands (Heptanisiakí), a lot of Italian influence.

- Ipirótiki (Epirotic cuisine).

- Kritikí (Cretan cuisine).[59][60][61]

- Kypriakí (Cypriot cuisine).

- Makedonikí (Macedonian cuisine).[62][63]

- Mikrasiatikí, from the Greeks of Asia Minor descent, including Polítiki (from Constantinople), from the tradition of the Greeks from Constantinople, a cuisine with significant Anatolian/Ottoman influence.[64][65][66]

- Pontiakí (Pontic Greek cuisine), found anywhere there are Pontic Greeks (Greeks from the Black Sea region).

- Thrakiótiki (Thracian cuisine).

Some ethnic minorities living in Greece also have their own cuisine. One example is the Aromanians and their Aromanian cuisine.

Typical dishes

[edit]Typical home-cooked meals include seasonal vegetables stewed with olive oil,[67] herbs, and tomato sauce known as lathera. Vegetables used in these dishes include green beans, peas, okra, cauliflower, spinach, leeks and others.[68][69][70]

Many food items are wrapped in filo pastry, either in bite-size triangles or in large sheets: kotopita (chicken pie), spanakopita (spinach and cheese pie), hortopita (greens pie), kimadopita (ground meat pie) also known as kreatopita (meat pie), kolokythopita (zucchini pie), and others. They have countless variations of pitas (savory pies).[71]

Apart from the Greek dishes that can be found all over Greece, there are also many regional dishes.[72][73]

North-Western and Central Greece (Epirus, Thessaly and Roumeli/Central Greece) have a strong tradition of filo-based dishes, such as some special regional pitas.

Greek cuisine uses seeds and nuts in everything from pastry to main dishes.[74]

A typical Greek-style breakfast,[55][75][76][77] and brunch,[78][79][80][81] consists of Greek coffee, frappé coffee, mountain tea, hot milk, fruit juice, rusks, bread, butter, honey, jam,[82] fresh fruits, koulouri (sesame bread ring, a type of simit), Greek strained yogurt,[83] bougatsa, tiropita, spanakopita, boiled eggs,[84][85][86][87][88] fried eggs,[89][90] omelette,[91][92] strapatsada, piroski, croissant,[93] tsoureki. A popular meal for breakfast is bougatsa provided mainly by bougatsadika shops selling bougatsa, pies, pastries, beverages. Traditional Greek breakfast was also providing in special dairy shops called galaktopoleia (milk shops)[94][95] have dairy products, milk, butter, yoghurt, sweets, honey, beverages, whereas today very few galaktopoleia shops exist.

The list of Greek dishes includes dishes found in all of Greece as well as some regional ones.[96][97][98][99]

Appetizers

[edit]

Selected appetizers are:[100]

- Antzougies,[101]

- Avgotaracho,[102] Bottarga, flathead mullet caught in lagoons with the well known the European and Greek Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) Avgotaracho Messolongiou from the Messolonghi-Etoliko Lagoons. The whole mature ovaries are removed from the fish, washed with water, salted with natural sea salt,[103] dried under the sun, and sealed in melted beeswax.

- Florina peppers,[104][105][106] it can be roasted, sliced and served by adding olive oil and garlic.

- Toursi (pickle),[107][108] with the well known the pickled peppers and mixed pickle.

- Feta topped with olive oil and oregano[109]

- Flogeres, crispy filo wrapped around a filling of goat cheese, herbs, sun-dried tomato, or ground meat.

- Sardeles psites (roasted sardines),[110]

- Htapodi sti schara (octopus on the grill),[111][112]

- Patatokeftedes,[113] patato fritters.

- Tirokroketes,[114][115] cheese fritters (fried cheese balls) also known as tirokeftedes.

- Bourekakia,[116][117][118] mini rolls filled with cheese or ground meat or vegetables.

- Kolokithokeftedes,[119][120][121][122][123] pumpkin fritters.

- Saganaki,[124][125] fried kefalograviera cheese.

- Melitzanes tiganites,[126] fried eggplants.

- Bouyiourdi,[127][128][129][118]

- Kafteri piperia (hot pepper),[130][131][132][133] with the well known the hot pepper tsouska, grilled or roasted chili pepper served with olive oil and vinegar.

- Lakerda,[134][135][136][137] pickled raw fish that is typically prepared with steaks of mature Atlantic bonito.

- Loutza

- Olives,[138][139][140]

- Kolokithakia tiganita,[141][142][143] fried cucurbita.

- Koxloi,[144][145] escargot, also is a main course.

- Htapodi ksidato,[146] octopus marinated in vinegar.

- Steamed mussels,[147][148][149][150]

- Omelette,[151][152]

- Strapatsada,[153][154][87] also known as kagianas, scrambled eggs (omelette) with tomato.

- Sfougato,[155][156][157][158] oven-baked omelette with eggs, grated zucchini, scallions (green onions), dill, feta cheese, kefalotyri or other type cheese, with the well known the sfougato from the islands of Mytilene, Santorini, Crete, it is also served as breakfast.

- Kalamarakia tiganita,[159][160][161][162][163] fried squid slices served with a lemon wedge.

- Dolmades,[164][165][166] also known as dolmadakia or sarmadakia, stuffed grape leaves.

- Ofti potato,[167][168] baked patato with coarse salt, dried oregano, olive oil, served with olives, chopped dried onion and lemon.

- Tomatokeftedes,[169][170] tomato fritters wider well known throughout the island of Santorini.

- Staka me ayga (staka with eggs),[171][172] a Cretan dish consisting of poached or fried eggs and local staka (a type of buttery cream mixed with flour).

- Gigantes plaki or gigandes plaki,[173][174][175][176] baked Greek Gigantes beans with tomato sauce and herbs, also is a main course. The cooking method plaki is food on a roasting tin that is baked or roasted in the oven with extra virgin olive oil, tomatoes, vegetables, and herbs, with the well-known gigantes beans plaki and fish plaki.[177]

- Marides tiganites,[178][179] small-sized whitebait fish (spicara smaris) that are lightly dusted with flour, then fried.

- Skordopsomo,[180] garlic bread made with a combination of sliced bread, olive oil, garlic, salt,[181] pepper, oregano, and basil.

- Garides saganaki,[182][183][184] sautéed shrimps that are deglazed with the ouzo, then doused in tomato sauce, and topped with crumbled feta.

- Dakos,[185][186][187] a traditional Cretan food features a slice of soaked dried bread or barley rusk (paximadi) topped with chopped tomatoes and crumbled feta or mizithra cheese, dried oregano and a few splashes of olive oil. Dakos is also deemed as a salad.

- Sikotakia (livers),[188] fried lamb or chicken small liver slices with olive oil and oregano. Also it serves as main dish known as "Tigania" which refers to the shallow pan in which the meal (pork or chicken or lamp) is cooked.

- Loukaniko (sausage),[189][190] Greek traditional sausage made from pork or lamb and typically flavored with orange peel, fennel seed, and various other dried herbs and seeds, and sometimes smoked over aromatic woods. They are also often flavored with greens, especially leeks.

- Fava,[191][192] yellow split peas that are cooked with onions and various spices until they transform into a creamy purée. It uses as a dip or a main course dish, with the well known the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) certified Fava Santorinis (Lathyrus clymenum).[193]

- Tsouknidopita (nettle pie),[194][195]

- Spanakopita (spinach pie),[196][197][198] spinach pie.

- Kimadopita (ground meat pie),[199] also known as Kreatopita (meat pie).[200]

- Hortopita (greens pie),[201][202] pie filled with a variety of wild or cultivated greens.

- Pitarakia,[203][204] mini half-moon-shaped mizithra cheese pies from the island of Milos.

- Kolokithopita (pumpkin pie),[205][206] savory pie with pumpkin and feta filling which is placed between two layers of phyllo pastry.

- Sfakiani pita or Sfakianopita (Sfakian pie),[207][208][209][210] traditional Cretan pan-fried thin flat pie from Sfakia stuffed with mizithra cheese drizzled with honey sometimes with sesame seeds, also served as a dessert.

- Tiropita (cheese pie),[211][212][213] pie with Greek feta cheese, also well known is Tiropitakia[214] which are mini cheese pies made with phyllo triangles stuffed with Greek feta cheese, and Tiropitakia Kourou[215] which has Kourou dough.

- Piroski or Pirozhki,[216][217] fried pita has filling of feta cheese or Greek Protected Destination of Origin (PDO) certified kasseri cheese or ground meat or mashed potato or other filling or mix filling. Serving hot. Most in the past time, also less still today, piroski can be found in Greece in specialty shops selling piroski exclusively.[218][219]

Salads

[edit]

In the Greek cuisine, appetizers are also the salads. Selected salads are:

- Horiatiki salad,[220][186][221][222] village's salad, a salad with pieces of tomatoes, cucumbers, onion, feta cheese (usually served as a slice on top of the other ingredients), and olives and dressed with oregano and olive oil.

- Horta salad,[223][224][225][226][227][228][229][230][231] greens salad, boiled Greek edible greens dressed with olive oil and fresh lemon juice, greens are like antidia (endives), vlita (amaranth greens), myronia (wild chervil), radikia (chicory), seskoula (chard), armyrithra, glistrida, styfnos, zoxos, asparagus.[232]

- Dakos,[185][186][187] or ntakos, traditional Cretan salad and appetizer.

- Pikantiki (also known as politiki), made with white cabbage and purple cabbage finely chopped, pickled Florina peppers, carrot, celery, parsley, finely chopped garlic, lemon juice, white vinegar, olive oil, salt.

- Lahanosalata,[233][234][235] cabbage salad, thinly chopped cabbage with salt, olive oil and lemon or vinegar juice.

- Kaparosalata,[236][237][238] caper salad with the well known the caper salad of the islands of Sifnos and Syros.

- Ampelofasoula,[239][240] cowpea salad.

- Kounoupidi (cauliflower),[241] salad with boiled cauliflower.

- Patatosalata,[242][243] potato salad with boiled potato.

- Patzarosalata,[244] beet salad with boiled beet.

- Brokolo (broccoli), salad with boiled broccoli.

- Aggouro-ntomata, cucumber with tomato.[221][245][246]

- Fasolia mavromatika,[247] black-eyed pea.

- Marouli,[248] lettuce salad.

- Tonosalata,[249] tuna salad.

Spreads and dips

[edit]

In the Greek cuisine, appetizers are also the spreads and dips, belong also to Greek sauces. Selected spreads and dips are:

- Olive paste,[250] tapenade.

- Rosiki,[251] boiled potatoes, carrot, cucumber, mayonnaise, pea.

- Kipourou, gardener's salad, cabbage, carrot, radish, mayonnaise.

- Kopanisti,[252][253][254] feta cheese, grilled red sweet peppers, olive oil, fresh garlic.

- Melitzanosalata (eggplant salad),[255][256] eggplant spread and dip (eggplant salads and appetizers).

- Skordalia,[257][258][259] garlic spread and dip from mashed potatoes, olive oil, vinegar, raw garlic.

- Tirokafteri,[260][261] spread and dip from feta cheese, yogurt, hot peppers, olive oil, and vinegar.

- Paprika,[262] sweet paprika, concentrate tomato paste, roasted red pepper (Florina pepper), feta cheese, olive oil.

- Taramosalata,[263][264] spread and dip from taramás fish roe mixed with olive oil, lemon juice, and a starchy base of bread or potatoes.

- Feta cheese sauce,[265] creamy sauce made from feta cheese, finely chopped garlic, crushed garlic, olive oil, lemon juice, oregano, thyme.

- Tzatziki,[266][267][268] spread and dip, strained yogurt or diluted yogurt mixed with cucumbers, garlic, salt, olive oil, sometimes with vinegar or lemon juice, and herbs such as dill, mint, parsley and thyme.

Soups

[edit]

Selected soups are:[269][270][271][272][273][274][275]

- Fasolada,[276][277][278][279][280] soup of dry white beans, olive oil, and vegetables.

- Fakes,[281] lentil soup.

- Hortosoupa (greens soup),[282] vegetable soup that comes in numerous versions.

- Avgolemono,[283] made with whisked eggs[284] and lemon juice that are combined in a broth. It is also a sauce.

- Youvarlakia,[285][286] soup from balls of ground meat, rice,[287] finished with avgolemono (the creamy egg and lemon sauce), cooked in a pot.

- Kotosoupa (chicken soup),[288][289] made from chicken broth, tender chicken cuts, various root vegetables, and rice, using many time avgolemono sause.

- Kremidosoupa (onion soup),[290]

- Kreatosoupa (meat soup),[291][292][293]

- Kakavia,[294][295] soup made from fishes, onions, potatoes, olive oil, and vegetables.

- Kokkinisto kritharaki,[296][297] also known as manestra soup, made from orzo (kritharaki, also known as manestra), onion, tomato sauce, olive oil.

- Magiritsa,[298][299][300] thick soup made with lamb offal (intestines, heart, and liver), dill, avgolemono sauce (egg and lemon beaten together), onion and rice, associated with the tradition where following the Resurrection on Greek Orthodox Easter Sunday people eat magiritsa soup.

- Ntomatosoupa (tomato soup),[301] with Greek ingredients.

- Patsas,[302][303] tripe soup made from lamb, sheep, or pork tripe as key ingredients, most use animal's head or feet and enrich the broth with garlic, onions, lemon juice, and vinegar.

- Revithosoupa (chickpea soup),[304][305] also known as revithada.

- Psarosoupa (fish soup),[306][307]

- Trahanas,[308][309][310][311] tarhana soup.

- Hilos,[312][313][314] porridge, it is typically for breakfast.

Dishes

[edit]

Selected dishes are:[315]

- Agkinares, cardoon has various recipes.[316]

- Fasolakia,[317][318][319] green beans that are simmered in olive oil with other vegetable ingredients, belongs to ladera which literally translating to "oily", vegetable dishes cooked in olive oil.[320]

- Arakas (pea),[321] belongs to ladera dishes, with the well-known dish "Arakas me Agkinares".[322]

- Bamies (okra),[323][324] belongs to ladera dishes.

- Briam,[325][326] also known as tourlou, belongs to ladera dishes, typically made from eggplants, zucchini, onions, potatoes, tomatoes, garlic, parsley.

- Gemista or Yemista,[327][328][329][330][331] "filled with" in Greek, baked stuffed bell peppers and tomatoes with rice or ground beef or both, onions, mint, parsley, olive oil.

- Lahanodolmades,[332][333] baked stuffed light green cabbage rolls with rice or ground beef or both, onions, mint, parsley, avgolemono sauce.

- Lahanorizo,[334] rice and cabbage, onions, fresh herbs, and the optional addition of tomato sauce.

- Prasorizo (leek and rice),[335] made from rice, chopped sweet leeks, olive oil, garlic, dill.

- Spanakorizo (spinach and rice),[336][337][338]

- Apaki,[339] cured pork meat. Left to marinate for two or three days in vinegar, the meat is then smoked with aromatic herbs and various spices. Apaki can be cooked on its own or added to other dishes.

- Stifado (stew),[340][341] casserole cooked with baby onions, tomatoes, wine or vinegar, olive oil, bay leaf, black pepper, meat such as pork, goat, rabbit, wild hare, beef, snails, tripe, octopus.

- Potatoes Yachni,[342][343][344][345] potatoes stew, potatoes simmered in a tomato sauce with onions, garlic, herbs and spices.

- Pastitsio,[346][347] baked pasta dish with ground meat and béchamel sauce.

- Astakomakaronada (lobster with spaghetti),[348][349] lobster meat that is coupled with a flavorful tomato-based sauce and served over pasta.

- Kokkinisto kritharaki,[296][297][350][351] tomato orzo (kritharaki, also known as manestra) stew.

- Makaronia me kima (spaghetti with ground meat),[352][353][354][355]

- Garidomakaronada (shrimps with spaghetti),[356][357]

- Melitzanes Papoutsakia,[358][359][360] baked eggplants stuffed with ground beef and topping it with a smooth béchamel sauce. The dish is called papoutsakia (little shoes) because its shape resembles little shoes.

- Kolokithakia gemista (stuffed zucchini), zucchini stuffed with rice and sometimes meat and cooked on the stovetop or in the oven.

- Spetsofai,[361][362] made with spicy country sausages, sweet peppers, onion, garlic, olive oil, in a rich tomato sauce.

- Giouvetsi,[363] pieces of lamb (or beef) and small noodles such as orzo, all cooked together in a tomato sauce with garlic and oregano.

- Gyros,[364] pork meat or chicken cooked on a vertical rotisserie, onions, tomato, lettuce, fried potatoes, sauces like tzatziki rolled in a pita bread.[365]

- Gogges (also called goggizes or gogglies),[366][367][368] a type of egg-free pasta made in the Peloponnese, especially in Argolis and Laconia.

- Hilopites,[369][370] traditional Greek pasta made from flour, eggs, milk, and salt, with the well known the hilopites Matsata.[371]

- Pastitsada,[372][373][374][375]

- Bourdeto,[376]

- Sofigado,[377][378][374][375] rabbit giouvetsi (stew) from the island of Kefalonia.

- Sofrito,[379][380][374][381][382] beef rump lightly fried with plenty of garlic and velvety sauce, from the island of Corfu.

- Mastelo,[383][384] roast lamb from the island of Sifnos.

- Roasted chicken with potatoes or rice,[385][386][387]

- Kleftiko,[388][389][390] slow-roasted leg of lamb or lamb shoulder wrapped in parchment paper with potatoes, bell peppers, onions, feta cheese, marinated with olive oil, lemon juice, garlic, fresh rosemary and herbs.

- Mousakas,[391][392][393] also known as moussaka, sliced tender eggplant cut lengthwise, or potato-based, lamb ground meat, topped with a thick layer of béchamel sauce.

- Moshari kokkinisto,[394][395] stewed veal meat, onions, garlic, olive oil, tomato sauce, served accompanied by basmati rice,[396][397] or pasta or potatoes or potato purée.[398] Kokkinisto is cooking meat or pasta, usually beef, pork, poultry, orzo, braised in tomato sauce.

- Keftedakia,[399][400][401] meat fritters, fried meatballs from lean ground beef with eggs, onions, garlic, parsley, mint, it also make them using half ground beef and half ground pork. A well known version is the shish kiofte (also known as kofta kebab) made from lamb.[402]

- Giaourtlou lamp kebab or Yiaourtlou lamp kebab,[403] traditional recipe from Asia Minor and Constantinople made from spicy ground lamb kofta kebab, yogurt sauce, tomato sauce.

- Soutzoukakia,[404] oblong shaped meatballs made with beef ground meat or mixed (beef, pork, lamp)[405] or chicken.[406]

- Soutzoukakia Smyrneika (Smyrna meatballs),[407][408][409][410][411][412] oblong shaped beef meatballs made with cumin and cinnamon, then simmered in a rich tomato sauce.

- Biftekia,[413][414][415][416][417] Greek-version burger patties made with a combination of ground pork, beef, or lamb,[418] and the meat is mixed with onions, breadcrumbs, eggs, parsley leaves finely chopped and oregano. They can grilled, baked or fried.

- Arni souvlas, whole lamb on the spit baked with rotisserie (electric- or gas-powered heating rotisserie) or over flaming charcoals (barbecue), specifically following the culinary tradition on Greek Orthodox Easter Sunday.[419][420][421][422]

- Arnaki sto fourno me patates (oven-baked lamb with potatoes),[423][424][425][426]

- Katsikaki ston fourno (oven-baked goat),[427]

- Paidakia,[428][429][430][431] ribs, with the well-knon the lamb chops.

- Gida vrasti (boiled goat),[432][433]

- Hirino me selino,[434][435][436] pork meat with celery.

- Souvlaki,[437][438][439][440] with the well known the souvlaki pita.[441]

- Kontosouvli,[442][443]

- Souvla,[444] large pieces of meat cooked on a long skewer over flaming charcoals (barbecue). It is also a technique of cooking meat. Also Antikristo[445] is a traditional technique of cooking meat on the island of Crete.

- Kokoretsi,[446][447] a dish consisting of lamb or goat intestines wrapped around seasoned offal, including sweetbreads, hearts, lungs, or kidneys, and grilled.

- Tigania,[448] pan-fried pork or chicken. The name "tigania" refers to the shallow pan in which the meal is cooked.

- Fagri sti schara (red porgy on the grill),[449]

- Gavros tiganitos (fried anchovy),[450]

- Gopes tiganites (fried boops boops),[451]

- Bakaliaros (merluccius merluccius),[452][453][454] cod fish, the most well-known recipe is the fried bakaliaros mainly served with skordalia dip and fried potatoes.

- Soupies (cuttlefish),[455][456]

- Xiphias or Xifias,[457][458] a species of swordfish.

Desserts and pastries

[edit]

Selected desserts and pastries (sweet and savory) are:[315]

- Amygdalopita (almond pie),[459][460][461] almond cake made with ground almonds, flour, butter, eggs and pastry cream.

- Amygdalota,[462][463][464][465][466][467][468] traditional sweet has several versions made from almonds, sugar and flower water.

- Akanés,[469][470][471] from Serres.

- Armenonville,[472][473][474] from Thessaloniki.

- Ashure,[475][468] also known as varvara.

- Avgato,[476][477] a spoon sweet of plum from the island of Skopelos.

- Akoumia,[478][479] a traditional dessert type of loukouma (donut) that is prepared on the island of Symi.

- Baklava,[480][481][482][483]

- Babas, rum baba.

- Gianniotikos Balkavas,[484][485] type of Baklava from Ioannina.

- Giaourtopita (yogurt pie),[486] yogurt cake with syrup.

- Bougatsa krema (bougatsa cream),[487][488][489][490]

- Copenhagen,[491] cake made off of two layers of filo, syrup, spread with butter, with a cream filling in between.

- Fanouropita,[492][493]

- Frigania,[494][495] from the island of Zakynthos.

- Fritoura,[496][468][497] from the island of Zakynthos.

- Flogeres,[498]

- Melomakarona,[499] they are also known as finikia.[500]

- Galaktoboureko,[501][502] custard cake with syrup.

- Galatopita (milk pie),[503][504][505][506] milk cake.

- Halvadopita (halva pie),[507] nougat pie, with the well-known the halvadopita from the islands of Chios and Syros.

- Hamalia,[508][509] a traditional dessert from the islands of Skiathos, Alonnisos and Skopelos.

- Kalitsounia or Lichnarakia,[510][511][512][513] from the island of Crete.

- Karydopita (walnut pie),[514][515] walnut cake.

- Karpouzopita (watermelon pie),[516][517] watermelon cake from the island of Milos.

- Kolokythopita (pumpkin pie),[518][519][520][521] sweet pie with yellow or red pumpkin.

- Krema (cream),[522][523] a traditional custard sweet with the well-known made with vanilla, chocolate, yogurt.

- Koliva,[524][525][526] boiled wheat kernels, honey, sesame seeds, walnuts, raisins, anise, almonds, pomegranate seeds, with powdered sugar on top. It is used as a ritual dish liturgically in the Eastern Orthodox Church religion, mostly prepared for commemorations of the dead, funerals, memorials.

- Koufeto,[527][528]

- Koufeto,[529][530][531] known as Koufeto of Milos, spoon sweet from the island of Milos.

- Koulourakia,[532]

- Kourampiedes,[533][534]

- Kydonopasto,[535][536]

- Korne,[537] Greek cream-filled puff pastry cone.

- Loukoumi,[538][539]

- Masourakia,[540][541] from the island of Chios.

- Melekouni,[542] from the island of Rhodes.

- Muhallebi or Mahallebi.[543]

- Moustalevria,[544][545][546]

- Moustokouloura,[547][548] grape must cookies.

- Mpezedes,[468][549] also known as mareges.

- Mandola,[550] almond candy from the island of Corfu.

- Mosaiko (mosaic),[551][552] also known as kormos or salami.

- Mamoulia,[553][554][555] traditional cookies from the islands of Chios and Crete.

- Melitinia,[556][557] a traditional dessert from the island of Santorini made from sweet cheese, sugar, eggs, a hint of mastic.

- Misokofti,[558][559] a traditional pudding-like dessert type of mustalevria from the island of Symi that's made with a combination of ripe fragosika (prickly pear) pulp, niseste (corn starch), and sugar.

- Pasteli,[560] sesame seed candy made from sesame seeds, sugar or honey pressed into a bar.

- Loukoumades,[561][562][563][564] fried balls of dough that are often spiced with cinnamon and drizzled with honey.

- Fouskakia,[565] a version of loukoumades from the island of Skopelos.

- Diples,[566] pastry sheets that are rolled, deep-fried, and doused or drizzled with a thick, honey-based syrup.

- Pastafrola,[567] also well known as pasta flora.

- Patouda,[568][569][570][571] cookies from the island of Crete combine flaky dough with a sweet nut-based filling.

- Petimezopita (petimezi pie),[572][573][574] grape syrup cake.

- Rizogalo,[575][576]

- Roxakia,[577][578][579]

- Sfoliatsa,[580] from the island of Syros.

- Stafidopsomo (raisin bread),[581]

- Sousamopita (sesame pie),[582] sesame cake with syrup.

- Sokolatopita (chocolate pie),[583][584] chocolate cake with syrup.

- Spatoula,[585][586] from Kalabaka, walnut cake with diplomat cream.

- Samsades,[587][588] a traditional dessert from the island of Limnos consisting of filo (phyllo dough) that's rolled around a filling of nuts, baked, and then drenched in sugar or honey syrup, thyme honey, or grape must (petimezi).

- Sykomaida,[589][590][591][592] a traditional dessert of fig cake from the island of Corfu made from dried figs, ground almonds or walnuts, ouzo, cinnamon, cloves, and fennel seeds.

- Poniro,[593][594]

- Spoon sweets,[595][596][597][598]

- Rodinia,[599][600] small rolls of marzipan that are wrapped with a layer of wiped cream and on their center have a whole cherry.

- Tiganita,[601][602][603] also known as laggita,[604] very thin tiganita is a Greek-style Crêpe,[605][606][607][608] thicker and fluffier tiganita is a Greek-style Pancake.[609]

- Tsoureki,[610]

- Vasilopita,[611] Greek New Year's cake with a coin or a trinket baked inside of it.

- Yogurt mousse,[612][613] mousse made from sheep's yoghurt.

- Strained yogurt with honey,[614][83] walnuts often added.

- Komposta,[615] made from peach, apple, pear or other fruits.

- Halvas with tahini,[616][617][618]

- Halvas with semolina,[619][620][621]

- Halvas sapoune,[622] also known as jelly halva, with the well known the Halvas Farsalon.

- Kariokes,[623][624] small sized walnut-filled chocolates and shaped like crescents.

- Kantaifi,[625][626]

- Kiounefe,[627][628][629]

- Kazan Dibi,[630]

- Revani,[631][632]

- Cretan Kserotigano,[633][634][635] sweet fritter from the island of Crete.

- Patsavouropita,[636][637] traditional filo pie sweet with a custard or savory with cheese filling.

- Portokalopita (orange pie),[638][639] orange cake with syrup.

- Milopita (apple pie),[640][641][642] apple cake.

- Melopita (honey pie),[643][644] honey cake, traditionally associated with the island of Sifnos.

- Saliaroi or Saliaria,[645] from Kozani.

- Samali,[646] extra syrupy Greek semolina cake with mastic. One of the traditional well-known sweets from Constantinople such as the Keşkül that is an almond-based milk pudding, Firin Sütlaç that is oven-baked rice pudding, Tavukgöğsü that is pudding made with shredded chicken breast.

- Trigona Panoramatos,[647][648][649][650] from the Panorama, Thessaloniki.

- Touloumba or Tulumba

- Ypovrihio or Ypovrichio,[651] means submarine in Greek, also known as vanilia or mastiha, a white chewy sweet that is served on a spoon dipped in a tall glass of cold water.

- Fetoydia,[652]

- Venizelika,[468] from the island of Limnos.

- Zoumero,[653] chocolate cake originating from Chania made with flour, baking powder, eggs, vanilla, and cocoa powder.

- Candied fruits,[654]

- Dried fruits,[655]

Drinks and beverages

[edit]

Selected drinks and beverages are:[656][657][658][659][660][661]

- Greek mountain tea

- Greek coffee,[662][663][664][665]

- Frappé coffee,[666][667] invented in Thessaloniki in 1957.[668][669][670][671]

- Freddo cappuccino,[672][673]

- Esspreso freddo,[674][675][676] iced coffee combines espresso and ice merely serve coffee over ice blends the two ingredients until the coffee is slightly chilled.

- Salepi,[677]

- Ouzo,[678][679][680]

- Retsina,[681]

- Tsipouro,[682]

- Tsikoudia,[683]

- Gin,[684][685][686][687]

- Liqueur,[688]

- Beer, Beer in Greece.[689][690][691][692][693]

- Souma,[694] from island of Chios.

- Tentura,[695] liqueur that hails from Patras.

- Kumquat, liqueur produced mainly on the island of Corfu.

- Kitron, or Kitro,[696] liqueur produced on the island of Naxos.

- Fatourada,[697] orange-flavored liqueur from the Greek island of Kythira.

- Mineral water, from several recognized water sources from Greece.[698][699][700]

- Sparkling mineral water, mineral carbonated water from sources from Greece.[698][699][700]

- Mastika, or mastiha, liqueur that is made with mastiha, mostly Chios Mastiha.[701]

- Soumada,[702] a non-alcoholic, syrupy, almond-based beverage that is produced on the island of Crete.

- Rakomelo,[703] made by combining raki or tsipouro - two types of grape pomace brandy - with honey and several spices, such as cinnamon, cardamom, or other regional herbs. It is produced in Crete and other islands of the Aegean Sea.

- Metaxa,[704] made from brandy, a secret combination of botanicals, and the aromatic and carefully selected Muscat wines from the island of Samos.

- Wine,[705][706][707][708][709][710] Greece has approximately 200 vine varieties[711] with the well-known,[712][713][714][715][716][717] Agiorgitiko,[718] Anthemis,[719] Assyrtiko,[720] Athiri, Begleri Ikaria,[721] Debina,[722] Fokiano Ikaria,[723] Kidonitsa,[724] Kotsifali,[725] Lagorthi, Limnio, Liatiko, Limniona,[726] Malagousia,[727] Mandilaria, Mantinia,[728] Mavrodafni, Mavrotragano,[729] Moschofilero,[730] Muscat of Limnos,[731] Naousa,[732] Negoska, Nemea,[733] Oinomelo,[734] Patras,[735] Roditis,[736] Rodola,[737] Romeiko, Samos nectar,[738] Samos Vin Doux,[739] Savatiano,[740] Vidiano,[741] Vilana,[742] Vinsanto (Visanto),[743][744] Xinomavro.[745]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^

- Tainter, Donna R.; Grenis, Anthony T. (1993). Spices and Seasonings: A Food Technology Handbook. New York: Wiley-VCH. p. 223.

- "Dictionary of Greek cuisine from Alpha to Omega letter" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- "Greece Gastronomy Map". Greek National Tourism Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023 – via Issuu.

- "Special quality identifying mark for the Greek cuisine - Evaluation Guide for catering business" (PDF) (in Greek). Ministry of Tourism. 2020. pp. 1–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2021.

- "The 10 best cuisines in the world - Where is Greece" (in Greek). 4 May 2023. Archived from the original on 8 May 2023.

- ^

- Renfrew, Colin (1972). The Emergence of Civilization; The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium B.C. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 280. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00011853.

- "Greek wine and culture". winesofgreece.org (in Greek). 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023.

- "A historical retrospective on Greece's wines". greekwinefederation.gr (in Greek). Greek Wine Federation. 30 June 2022. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023.

- ^

- "List of the Greece's PDO (Protected Designation of Origin)-certified and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication)-certified products and specifications: Fruits, Vegetables, Nuts, Legumes" (in Greek). Ministry of Rural Development and Food. Archived from the original on 11 January 2024.

- "Sustainability on the plate: Ingredients used in Greek food and recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^

- "Cusina Caruso: 12 secrets for proper boiling of pasta" (in Greek). 26 June 2024. Archived from the original on 26 June 2024.

- "The correct boiling of pasta" (in Greek). 21 June 2023. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- Tsiropoulou, Evi (4 October 2024). "Pasta: What is the right way to re-heat them?" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 October 2024.

- ^

- "List of the Greece's PDO (Protected Designation of Origin)-certified and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication)-certified products and specifications: Cheeses" (in Greek). Ministry of Rural Development and Food. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024.

- "21 Greek Protected Destination of Origin (PDO) cheeses" (in Greek). 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- "52 light cheeses that we eat on a diet and they are all Greek" (in Greek). 15 May 2024. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024.

- ^

- "The art of ladolemono (olive oil-lemon dressing) sauce: All the secrets for the most popular Greek dressing" (in Greek). 31 August 2018. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- "The right ladolemono (olive oil-lemon dressing) sauce for the food" (in Greek). 17 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022.

- Ismyrnoglou, Nena. "4 light ladolemono version sauces for each cooking" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 July 2024.

- ^

- "List of the Greece's PDO (Protected Designation of Origin)-certified and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication)-certified products and specifications: Oils and Olives" (in Greek). Ministry of Rural Development and Food. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023.

- "Olive: History, tradition, roots and identity" (in Greek). 5 November 2022. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022.

- "Greek Liquid Gold: Authentic Extra Virgin Olive Oil". Archived from the original on 22 May 2024.

- ^

- "Ancient Greek cuisine: The "healthy in body" in practice" (in Greek). 5 October 2021. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021.

- "Discrimination in professional kitchens is an ancient history" (in Greek). 8 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023.

- ^

- "33 famous Italian desserts" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 23 June 2024.

- "Italian Cuisine: 13 Italian dishes you must try" (in Greek). 15 December 2023. Archived from the original on 4 January 2023.

- "The Italian gastronomic culture" (in Greek). 17 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- "The Cypriot gastronomic culture" (in Greek). 1 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- "Over 4,000 Cypriot cuisine recipes". kathimerini.com.cy (in Greek). Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- "Cypriot nutrition and gastronomy" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 21 March 2023.

- ^ "The eating habits of the ancient Greeks" (in Greek). 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Ancient Athens, What did the Ancient Athenians eat?" (in Greek). 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023.

- ^ "Symposium: Ancient Greek and Byzantine gastronomy" (in Greek). 8 May 2011. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020.

- ^ Mallos, Tess (1978). Greek Cookbook. Dee Why: Summit Books. ISBN 0-7271-0287-7.

- ^ Renfrew, Colin (1972). The Emergence of Civilization; The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium B.C. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 280. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00011853.

- ^ "Why Cypriot and Greek Food are Similar Yet Different". 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023.

- ^ Katz, Solomon H.; McGovern, Patrick; Fleming, Stuart James (1996). Origins and Ancient History of Wine (Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology). London: Routledge. p. x. doi:10.4324/9780203392836. ISBN 90-5699-552-9.

- ^ Wilson, Nigel Guy (2006). Encyclopedia of ancient Greece. New York: Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 0-415-97334-1.

- ^ Civitello, Linda (2011). Cuisine and Culture: A History of Food and People. New York: Wiley. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-470-40371-6.

- ^ Kiple, Kenneth F. (2007). A movable feast: ten millennia of food globalization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-521-79353-7.

- ^ "Makedonia and Thrace: Products of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI)" (PDF) (in Greek). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Eastern Makedonia and Thrace: Local products". emtgreece.com (in Greek and English). Archived from the original on 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Peppers (spice) of the world: The known, the special and how to use them" (in Greek). 17 July 2023. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "How to cook with spices: 6 tips and the necessary tools" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Curry and other masala: Everything about Indian spice blends" (in Greek). 9 June 2023. Archived from the original on 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Meat: Do we salt before or after baking?" (in Greek). 6 July 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Cheeses in Greece". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Taverna food: 30 recipes from tavernas of Athens" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 22 May 2024.

- ^ "City of Athens: Gastronomy Culture". cityfestival.thisisathens.org (in Greek and English). Athens. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

Athens Cocktail Week, Athens Street Food Festival, World of Beer Festival, Athens Wine Selfie, Food & Wine Museum Sessions

- ^ "The Flame Festival" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Athens Coffee Festival" (in Greek and English). Archived from the original on 11 September 2024.

- ^ Veloudaki, Afroditi; Zota, Konstantina, eds. (2014). Dietary Guidelines for Adults (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: Prolepsis Institute of Preventive Medicine, Environmental and Occupational Health. pp. 1–245. ISBN 978-960-503-555-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2024 – via Asclepius Medical Association of Trikala.

- ^ "The Greek tavern food in 30 recipes" (in Greek). 5 June 2019. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024.

- ^ "When and how Greeks eat". Ultimate Guide to Greek Food. Archived from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "What to eat when it's heatwave weather: tips and instructions" (in Greek). 11 July 2023. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024.

- ^ "10 tips for smart refrigerator maintenance" (in Greek). 19 October 2023. Archived from the original on 4 November 2024.

- ^ "The Best Burgers in Athens - the Street Food That Became an Art" (in Greek and English). Archived from the original on 6 July 2024.

- ^ Tsakiri, Tonia (25 May 2011). "Goody's won the "war" against McDonald's" (in Greek). To Vima. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ^ "UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH): Listing of ICH and Register, Greece". UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. Archived from the original on 9 November 2024.

- ^ "Sustainability on the plate: Stale bread" (in Greek). 29 May 2024. Archived from the original on 6 June 2024.

- ^ "What our ancient ancestors ate and drank?" (in Greek). 2 January 2021. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024.

- ^ Maria Gkirtzi (7 July 2014). "Ancient and Byzantine flavours through different perspectives (Part A)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 8 November 2023.

- ^ Psaliou, Xenia (2021). The diet of the Greeks from ancient times until today (PDF) (Bachelor's degree thesis) (in Greek). Hellenic Mediterranean University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2024.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew; Dalby, Rachel (2017). Gifts of the gods: a history of food in Greece. London: Reaktion Books. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-78023-854-8. OCLC 1026820535.

- ^ Zoi Parasidi (14 November 2020). "What is the new identity of Greek cuisine?" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 29 March 2023.

- ^ Karagianni, Vasiliki (2011). The history and the development of Greek culinary art (PDF) (Bachelor's degree thesis) (in Greek). Patras: Technological Educational Institute of Western Greece. pp. 1–57. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Greek cuisine as a tool to promote tourism and exports" (in Greek). 25 May 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024.

- ^ "Zisis Kerameas: The Teacher" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 5 December 2023.

- ^ "Annual Symposium: 30 years of the Culinary Professionals Greece". culinaryprofessionals.gr (in Greek). 1 April 2024. Archived from the original on 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Greece Gastronomy Map". Greek National Tourism Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023 – via Issuu.

- ^ "Local cuisines in Greece" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 23 September 2023 – via Issuu.

- ^ "Greek gastronomy guide, regions of Greece". greekgastronomyguide.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Gastronomy & Wine Tourism and the network of Gastronomic Communities". greekgastronomyguide.gr. Archived from the original on 22 September 2024.

- ^ "Gastronomic Communities - Gastronomy & Wine Tourism". greekgastronomyguide.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on 22 September 2024.

- ^ "Taste Atlas: second in the world for Greek cuisine - The 3 dishes that stood out" (in Greek). 13 December 2023. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Greek Breakfast". greekbreakfast.gr (in Greek and English). Archived from the original on 29 February 2024.

- ^ "The Greek breakfast experience". discovergreece.com. 15 March 2023. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Recipes from the local cuisines of Greece" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Messinian Food, Food, Recipes, Traditional Tools, Preparation Techniques". messiniandiet.gr (in Greek and English). Virtual Museum of the Messinian Diet. Archived from the original on 18 May 2025.

- ^ "The whole of Crete: Local flavours from restaurants, taverns, coffee shops". Gourmet (BHMA Gourmet) (in Greek). No. 34. Athens: To Vima. 2009. pp. 6–63.

- ^ "Cretan Gastronomy recipes". cretangastronomy.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 August 2024.

- ^ "The tour of Crete in 20 kafenia (coffee shops)" (in Greek). 23 August 2024. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024.

- ^ "Greek Macedonian cuisine". macedoniancuisine-pkm.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Thessaloniki: 23 recipes from the most fusion cuisine in Greece" (in Greek). 7 October 2022. Archived from the original on 6 December 2023.

- ^ "The gastronomy of Politiki Cuisine" (in Greek). 12 May 2015. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024.

- ^ "The magnificent Politiki Cuisine" (in Greek). 3 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- ^ "15 traditional recipes from the Constantinople, for the summer" (in Greek). 19 August 2022. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Cooking with less oil: 6 ways to do it" (in Greek). 5 July 2024. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024.

- ^ "List of the Greece's PDO (Protected Designation of Origin)-certified and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication)-certified products and specifications: Fruits, Vegetables, Nuts, Legumes" (in Greek). Ministry of Rural Development and Food. Archived from the original on 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Authentic Greek Cuisine Awards" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Greece Gastronomy". Greek National Tourism Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023 – via Issuu.

- ^ "Culinary Cultural Heritage of Greece: The Pie" (PDF) (in Greek and English). Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports. 2016. pp. 1–122. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2024 – via Greece’s National Intangible Cultural Heritage Registry.

- ^ Kartsagkouli, Ntiana (30 April 2023). "The Greek History through food" (in Greek). To Vima. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023.

- ^ "The Gastronomic Guide of Greece is being drafted" (in Greek). 31 May 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024.

- ^ Vasilopoulou, Effie; Dilis, Vardis; Trichopoulou, Antonia (2013). "Nutrition claims: A potentially important tool for the endorsement of Greek Mediterranean traditional foods". Mediterranean Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 6 (2): 105–111. doi:10.1007/s12349-013-0123-5. S2CID 72718788.

- ^ "Greek Breakfast - Handbook for Hoteliers" (in Greek). Hellenic Chamber of Hotels. pp. 1–116. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023 – via Issuu.

- ^ "Breakfast: 32 recipes to get the day off" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Greek breakfast options" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 7 April 2024.

- ^ "Recipes for breakfast and brunch" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 11 June 2024.

- ^ "How to prepare an unforgettable brunch at home (+ 43 recipes)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 11 June 2024.

- ^ "31 places for brunch meals" (in Greek). 12 November 2021. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Fasting breakfast: 7 complete suggestions for Holy Week" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Jams: 24 favorite recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Yogurt desserts: 27 light recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Learn all about eggs and make 35 unique recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 19 September 2024.

- ^ "How to boil an egg perfectly (depending on how you eat it)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Cusina Caruso: All the secrets for the egg exact boiling times and the ideal peeling" (in Greek). 16 October 2024. Archived from the original on 4 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Summer eggs: 55 special easy recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 21 August 2024.

- ^ "Scrambled eggs and 8 different ways to make them" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 31 March 2023.

- ^ Ismyrnoglou, Nena (2 September 2022). "Fried eggs (eyes) and 9 great ways to make them" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 21 August 2024.

- ^ Pistikou, Magda (5 October 2023). "The perfect fried eggs (eyes) and 10 professional secrets" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 11 September 2024.

- ^ Stamatiadou, Angela (9 July 2024). "Omelette: Its history, many origins and versions-celebrities" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "The ultimate toast with omelette" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Single-serving baked goods: Kouign Amann, Pastel de nata, Cruffin (croissant and muffin), Bostock (brioche with almonds), Cardamom bun (kardemummabullar), Cannelé, Palmier" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 13 June 2024.

- ^ Papastamou, Georgia (8 February 2022). "In the old milk shops of Athens" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 September 2024.

- ^ Konstantinidou, Vivi (14 April 2022). "Galaktoboureko, where does it come from?" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 September 2024.

- ^ "Greek cuisine is the modern epic of Greece" (in Greek). Ta Nea. 22 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018.

- ^ "The unique oil dishes of the Greek cuisine" (in Greek). 25 August 2021. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022.

- ^ "Mezedopolia: The temples of Greek cuisine" (in Greek). 3 June 2022. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022.

- ^ Konstantinidou, Vivi (20 August 2024). "The Greece of meze: What do they eat in Mytilene, what in Tyrnavos and what in Crete?" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 21 August 2024.

- ^ "Appetizers - Mezedes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 23 September 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Antzougia". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Avgotaracho Messolongiou". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "25 secrets about salt in the kitchen" (in Greek). 7 August 2016. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Florina peppers". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Florina peppers for all year round recipe" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 22 June 2024.

- ^ "How do we easily remove the peel of the pepper" (in Greek). 4 July 2024. Archived from the original on 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Vegetable pickles in 10 different versions from all over Greece" (in Greek). 28 November 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Torshis: mezes" (in Greek). 1 August 2024. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024.

- ^ "Feta". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Sardeles psites (roasted sardines)". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 October 2024.

- ^ "Grilled Octopus (Chtapodi or Htapodi sti schara)". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Octopus: 30 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Potato fritters" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Tirokroketes". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Chef on Air on Sky TV: Tirokeftedes". chefonair.gr (in Greek). Chef on Air. 5 April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Bourekakia of cheese" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ Papadopoulou, Themis. "Smyrna bourekakia" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b "10 appetizers with cheese" (in Greek). 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Kolokithokeftedes: 11 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Kolokithokeftedes (pumpkin fritters): 10 repipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Pumpkin fritters VS Tomato fritters: 25 recipes and all the secrets to make them" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 12 June 2024.

- ^ "Keftedes: 3 fritter recipes for summer feasts". 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Vegetable-balls: 37 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 8 July 2024.

- ^ "Saganaki". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022.

- ^ "Cheeses ideal for fried cheese and 10 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Eggplants in the pan in 2 ways" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Bouyiourdi" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Bouyiourdi by chef Christoforos Peskias" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Saganaki, Bouyiourdi, Omelets: 12 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Hot peppers" (in Greek). 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Paprika, bukovo (crushed red pepper), chili, and other peppers" (in Greek). 19 May 2017. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "18 types of peppers and how "hot" they are" (in Greek). 20 September 2021. Archived from the original on 5 July 2024.

- ^ "12 secrets for cultivation of pepper" (in Greek). 22 May 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Lakerda". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024.

- ^ "Handmade lakerda step by step by chef Lefteris Lazarou" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 27 September 2024.

- ^ Soylios, Giannis. "Lakerda recipe" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Homemade lakerda step by step from the chef Niki Chrysanthidou" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 November 2024.

- ^ "List of the Greece's PDO (Protected Designation of Origin)-certified and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication)-certified products and specifications: Oils and Olives" (in Greek). Ministry of Rural Development and Food. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023.

- ^ "Best rated Greek Olives". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ Vassilopoulou, Maria (23 October 2025). "How to Make Homemade Olives". Archived from the original on 23 October 2025.

- ^ "Kolokithakia tigantita". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Zucchini in 46 ways" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Pumpkins in the pan with staka and mint" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Kohli bourbouristi". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Oily and garlicky koxlioi (snails) with amaranth greens and zucchini blossoms" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Οctopus marinated in vinegar - wine" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Mydia". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Steamed mussels in wine and mustard" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ Makrionitou, Nikoleta (15 March 2024). "Shells: Species, how to cook them and what to watch out for" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Cusina Caruso: Steamed Marinier Mussels, their Secrets & the Busting of a Myth" (in Greek). 7 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Omelleta". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Brunch meals". tasty-guide.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 November 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Strapatsada". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Kagianas (Strapatsada): 12 unique recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Sfougato". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ Spanoudaki, Kyveli. "Sfougato from Mytilene" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ Ismyrnoglou, Nena. "Sfougato with zucchini and fresh scallions" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Sustainability on the plate: Pumpkin" (in Greek). 29 May 2023. Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Kalamarakia tiganita". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Fried squid with spiced semolina" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 7 December 2022.

- ^ "Kalamarakia on CNN's List of the World's Best Fried Food". 19 May 2022. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Squid: How to clean, fry and roast them" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Squids: 25 recipes for the weekend" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Dolmadakia: 17 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Dolmadakia yalanci" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Dolmadakia, sarmadakia or giaprakia yalanci" (in Greek). 1 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Ofti patato" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 25 September 2024.

- ^ Kassapaki, Vaggelio (1 November 2015). "Ofti potatoes stuffed with cheeses". cretangastronomy.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Tomatokeftedes". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Tomatokeftedes (tomato fritters)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 13 June 2024.

- ^ "Staka with eggs". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024.

- ^ Mitarea, Niki (30 March 2024). "Cretan staka: You can make it at home" (in Greek). LiFO. Archived from the original on 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Gigandes plaki". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ Ismyrnoglou, Nena. "Gigantes plaki with herbs" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 18 September 2024.

- ^ Ismyrnoglou, Nena. "Gigantes plaki with fresh tomato, mint and bukovo" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Cusina Caruso: Gigantes beans - Roasted butter beans from Prespes Lakes". Archived from the original on 26 June 2024.

- ^ Makrionitou, Nikoleta. "Plaki: Its history and 7 Greek recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Marides tiganites". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023.

- ^ Stamatiadou, Angela; Tzialla, Christina. "Fish in the pan: 14 recipes for anchovy, sardines, roe and more" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Skordopsomo". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "25 Secrets of salt in the kitchen" (in Greek). 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Garides saganaki". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Shrimps Saganaki" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 30 March 2023.

- ^ "Shrimps: 23 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Dakos". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 23 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Top 100 Salads in the World". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Dakos the Cretan, the Greek: 18 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Sikotakia with olive oil and oregano" (in Greek). 5 March 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Loukaniko". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Recipes with Sausages" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 21 February 2024.

- ^ "Fava". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Fava throughout Greece: All Greek varieties and 15 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Fava Santorinis". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Tsouknidopita". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 6 September 2024.

- ^ Eksiel, Robbie (4 November 2022). "Mission in Pindos: Traditional nettle pie with handmade dough, the recipe" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Spanakopita". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Spanakopita: 18 recipes for the traditional Greek pie" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 17 April 2024.

- ^ "The best spinach pies in Athens: Which ones stand out and why" (in Greek). 15 September 2023. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Kimadopita: 6 recipes from Smyrna, Thrace, Pontus" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 September 2024.

- ^ "Kreatopita (meat pie)". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 October 2024.

- ^ "Hortopita". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Traditional hortopita recipe" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Pitarakia". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Traditional Pitarakia of Milos" (in Greek). 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Kolokithopita". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Kolokithopita pie: 10 special sweet and savory recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ Mathioudaki, Eva. "Sfakiani pie with thyme honey" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ Delidimou, Katerina. "Sfakia Pie (Sfakianì Pita)". culinaryflavors.gr (in Greek and English). Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ Kati, Antonia. "Pan-fried sfakiani pie" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ Konstantinidou, Vivi. "Traditional pies: 3 legendary recipes from Crete" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Tiropita". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Tiropita: 32 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 22 March 2023.

- ^ Papastamou, Georgia (15 October 2024). "Cheese pie is not just one: 10 delicious versions" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Tiropitakia: 25 recipes from all over Greece" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 26 September 2023.

- ^ "Tiropitakia Kourou with yogurt" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Piroski from Pontus" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Piroski with ground meat step by step" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Where to eat good cheese pies and piroskoi in Piraeus, Greece" (in Greek). LiFO. 6 November 2022. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023.

- ^ ""Piroski" in the renovated Modiano Market in Thessaloniki" (in Greek). Makedonia. 8 May 2023. Archived from the original on 11 May 2023.

- ^ "Greek salad (Horiatiki salata)". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b "How to preserve tomatoes for longer" (in Greek). 5 June 2024. Archived from the original on 5 June 2024.

- ^ "From 20 Greek places: How they make the Greek horiatiki salad all over the country" (in Greek). 26 June 2024. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Hortas: 6 secrets from cleaning to cooking" (in Greek). 30 April 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023.

- ^ "Horta: All the secrets from cleaning to cooking and 25 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ "The known and unknown Greek horta and how to cook them" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Learn to distinguish summer horta (leafy greens)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Sustainability on the plate: Leaf celery, celery, celery root" (in Greek). 19 February 2024. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Lettuce: This is the best way to store it" (in Greek). 8 May 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Picking wild leafy greenss: Complete guide to identify them" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 23 May 2024.

- ^ Makrionitou, Nikoleta (13 April 2023). "Greek spring leafy greens: Known and unknown species" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Sustainability on the plate: Asparagus" (in Greek). 27 March 2024. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Asparagus: 40 recipes with the vegetable loved by the ancient Greeks". Archived from the original on 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Lahanosalata". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Cabbage salad with yoghurt sauce" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 3 August 2021.

- ^ "Cabbage salad with sour apple and yoghurt sauce" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 3 October 2023.

- ^ "Kaparosalata". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 10 September 2024.

- ^ Koustoudis, Asterios. "Caper salad in 2 ways" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 15 September 2024.

- ^ Lebesi-Narli, Maro. "Kapari salad from Sifnos island" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Ampelofasoula with tomato, olive oil and lemon" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Ampelofassoula or Louvi (Fresh Black Eyed Peas) and Marida (Picarel)". Archived from the original on 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Cauliflower: 20 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Patatosalata". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Potato salad with pickled samphire and graviera cheese" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Pantzarosalata". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ Konstantinidou, Vivi (4 September 2024). "Explainer: Everything you need to know about Greek tomatoes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 September 2024.

- ^ "What tomatoes can we find in Greece?" (in Greek). 20 August 2023. Archived from the original on 15 August 2024.

- ^ "Black-eyed peas in 18 nutritious recipes" (in Greek). 9 May 2024. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024.

- ^ Mais, Eleni; Mais, Loxandra. "Politiki lettuce salad" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Tonosalata". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Olive paste with oregano" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Russian salad, the original (or Olivier salad)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 29 October 2018.

- ^ "Kopanisti". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 25 August 2024.

- ^ Makrionitou, Nikoleta. "Kopanisti: Cycladic cheese" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 7 April 2024.

- ^ Rentoulas, Angelos (26 November 2014). "Kopanisti of Mykonos: The most rock cheese" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Melitzanosalata". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Melinatzosalates: 8 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Skordalia". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Two Greek skordalia for the cod of 25th of March" (in Greek). LiFO. 25 March 2024. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Greek Spreads: Taramasalata, Tzatziki, Spicy Cheese, Eggplant & Garlic Dip". 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Tirokafteri". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Tirokafteri" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Paprika, bukovo (crushed red pepper), chili, and other peppers" (in Greek). 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Taramosalata". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022.

- ^ "Taramosalata" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ Kontomitros, Nikos (19 August 2022). "Feta cheese sauce" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Tzatziki". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Tzatziki: The secrets" (in Greek). 25 June 2021. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Tzatziki recipe and how to make it" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Secrets for cooking the soup" (in Greek). 23 January 2019. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Winter soups" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Vegetable soups: The most delicious combinations and 20 top recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 19 September 2024.

- ^ "The right skimming in cooking with a pot" (in Greek). 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- ^ "The map of Greek legumes: Places famous for their lentils, chickpeas and beans" (in Greek). 25 January 2024. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Legumes: How to soak them and make them correctly mushy - soaking and boiling times" (in Greek). 15 April 2024. Archived from the original on 6 June 2024.

- ^ "10+1 secrets for cooking legumes" (in Greek). 21 May 2019. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Fasolada". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024.

- ^ Ismyrnoglou, Nena. "Fasolada soup (video)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Fasolada soup: All the secrets and 13 delicious recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Traditional fasolada soup" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 February 2024.

- ^ "Classic and traditional fasolada soup" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Fakes". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Hortosoupa". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Avgolemono (soup)". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 October 2024.

- ^ "Eggs: What to look out for when buying them, according to Hellenic Food Authority (EFET)" (in Greek). 28 August 2025. Archived from the original on 6 September 2025.

- ^ "Youvarlakia". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Yuvarlakia: 11 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 March 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Rice: How do we reheat it without drying it out?" (in Greek). 1 November 2024. Archived from the original on 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Kotosoupa". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Chicken soup: 17 recipes we cook all the time" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 23 December 2024.

- ^ "French onion soup" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Kreatosoupa". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ Driskas, Vaggelis. "Kreatosoupa (meat soup)" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 27 March 2024.

- ^ "How to make soups like those made by "Epiros" in Varvakeio Market (Central Municipal Athens Market)" (in Greek). LiFO. 16 February 2024. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024.

- ^ "Kakavia". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "The perfect Kakavia" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Kritharaki". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 19 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Greek Manestra". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Magiritsa". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Magiritsa soup: 23 special recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 11 May 2024.

- ^ "The ultimate guide to Greek Easter". 8 April 2023. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Aromatic tomato soup" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 4 October 2023.

- ^ "Patsas". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022.

- ^ "The veal patsas of Tsarouhas" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Revithia soup: 9 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 19 October 2023.

- ^ Mastora, Dora (10 December 2021). "The perfect chickpea recipe" (in Greek). LiFO. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Psarosoupa". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023.

- ^ "Fish soup: 15 unique recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Trahana". TasteAtlas. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024.

- ^ "The types of trachanas" (in Greek). 12 February 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Trahanas: 21 recipes" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 18 February 2024.

- ^ "We cook trahanas: The times, the herbs and all the secrets" (in Greek). 13 February 2019. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Porridge with yoghurt, oats, apple and cocoa" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Porridge with tahini and fresh fruit" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 5 January 2024.

- ^ "Homemade muesli with spices and dried fruit" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 26 February 2024.