Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to List of mausolea.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of mausolea

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum may be considered a type of tomb, or the tomb may be considered to be within the mausoleum. This is a list of mausolea around the world.

Africa

[edit]Algeria

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania | Tipaza Province | A monumental tomb of the Numidian Berber king Juba II and Queen Cleopatra Selene II. |

|

| Madghacen | Batna Province | A royal Numidian mausoleum dating back to the 3rd century BC. |

|

| Jedars | South of Tiaret | A series of thirteen ancient monumental Berber mausoleums. |

|

| Tomb of Masinissa | El Khroub | The tomb of Masinissa, an ancient Numidian king. |

|

| Mausoleum of Sidi Abderrahmane Et-Thaalibi | Algiers | The tomb of the patron saint of Algiers, Sidi Abderrahmane Et-Thaalibi. |

|

| El Alia Cemetery | Oued Smar | A cemetery in Algiers that contains the graves of numerous Algerian historical figures, including former presidents. |

Benin

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Hubert Maga | Parakou | The tomb of Hubert Maga, the first President of Dahomey (now Benin). | |

| Mausoleum of Mathieu Kérékou | Natitingou | The resting place of Mathieu Kérékou, who served as President of Benin from 1972 to 1991 and again from 1996 to 2006.[1] |

|

Burundi

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Pierre Nkurunziza | Gitega | The resting place of Pierre Nkurunziza, President of Burundi from 2005 to 2020. The mausoleum is officially named Mausolée du Guide Suprême du Patriotisme (Mausoleum of the Supreme Guide of Patriotism).[2] |

Comoros

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Ahmed Abdallah | Domoni | The tomb of Ahmed Abdallah, the first, third, and fifth President of the Comoros. |

Republic of the Congo

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Marien Ngouabi | Brazzaville | A memorial and tomb for Marien Ngouabi, the third President of the Republic of the Congo. | |

| Mausoleum of Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza | Brazzaville | A large memorial containing the remains of the Italo-French explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza and his family. |

|

Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Laurent-Désiré Kabila | Kinshasa | The resting place of Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the third President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, located in front of the Palais de la Nation.[3] |

|

| Mausoleum of Joseph Kasa-Vubu | Tshela | The tomb of Joseph Kasa-Vubu, the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. |

Eswatini

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| King Sobhuza II Memorial Park | Lobamba | A memorial and mausoleum for King Sobhuza II, who reigned for 82 years, one of the longest verifiable reigns of any monarch in recorded history. |

|

Ethiopia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grave of Meles Zenawi | Holy Trinity Cathedral, Addis Ababa | The burial site of Meles Zenawi, who served as President and later Prime Minister of Ethiopia. The cathedral is the final resting place of many notable Ethiopians, including Emperor Haile Selassie. |

Gabon

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Omar Bongo | Franceville | A large, private mausoleum for Omar Bongo, who was President of Gabon for 42 years, from 1967 until his death in 2009.[4] | |

| Mausoleum of Léon M'ba | Libreville | A memorial tomb for Léon M'ba, the first President of Gabon. |

Ghana

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum | Accra | A memorial park and mausoleum dedicated to Kwame Nkrumah, the first President of Ghana and a leading figure in the pan-African movement. |

|

| Asomdwee Park | Accra | The burial site of John Atta Mills, the third President of the Fourth Republic of Ghana. |

|

Guinea

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camayanne Mausoleum | Within the Grand Mosque of Conakry, Conakry | The resting place of Guinea's national heroes, including Ahmed Sékou Touré, Samori Ture, and Alfa Yaya of Labé.[5] |

Guinea-Bissau

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Amílcar Cabral | Bissau | A memorial and tomb dedicated to Amílcar Cabral, an anti-colonial leader, intellectual, and diplomat. |

|

Ivory Coast

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Félix Houphouët-Boigny | Yamoussoukro | The family tomb of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the first President of Ivory Coast, located near the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro. |

Kenya

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Jomo Kenyatta | Nairobi | The resting place of Jomo Kenyatta, the first President of Kenya, located on the grounds of the Parliament Buildings. Access is generally restricted.[6] |

|

| Tom Mboya Mausoleum | Rusinga Island | A mausoleum dedicated to Tom Mboya, a prominent Kenyan trade unionist and politician who was assassinated in 1969. |

Liberia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centennial Pavilion | Monrovia | The final resting place of former president William Tubman. The pavilion is also used for presidential inaugurations. |

Malawi

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kamuzu Mausoleum | Lilongwe | A monumental marble and granite tomb dedicated to Malawi's first president, Hastings Kamuzu Banda.[7] |

|

| Bingu wa Mutharika Mausoleum | Thyolo District | A large, modern mausoleum known as "Mpumulo wa Bata" (Peaceful Rest), housing the remains of Bingu wa Mutharika, the third President of Malawi. |

Mozambique

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Praça dos Heróis Moçambicanos (Heroes' Square) | Maputo | A national monument and public square that serves as the burial site for Mozambique's national heroes, including Samora Machel and Eduardo Mondlane.[8] |

|

Namibia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heroes' Acre | Windhoek | An official war memorial of the Republic of Namibia. It includes a cemetery with the graves of national heroes and heroines, as well as an eternal flame and a large obelisk. |

|

Nigeria

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Nnamdi Azikiwe | Onitsha | A mausoleum dedicated to Nnamdi Azikiwe, the first President of Nigeria. |

|

| Tomb of Abubakar Tafawa Balewa | Bauchi | The final resting place of Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, the first and only Prime Minister of independent Nigeria. |

|

| Mausoleum of Sani Abacha | Kano | The tomb of Sani Abacha, the de facto President of Nigeria from 1993 to 1998. |

|

South Sudan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of John Garang | Juba | The final resting place of Dr. John Garang de Mabior, a Sudanese politician and revolutionary leader, and the first President of Southern Sudan.[9] |

|

Sudan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of The Mahdi | Omdurman | The tomb of Muhammad Ahmad, a Sudanese religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, on 29 June 1881, proclaimed himself the Mahdi. |

|

Tunisia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bourguiba mausoleum | Monastir | A monumental grave in Monastir, Tunisia, housing the remains of the former president Habib Bourguiba, the father of Tunisian independence. |

|

Togo

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Gnassingbé Eyadéma | Pya, Kara | The family mausoleum of Gnassingbé Eyadéma, who was the President of Togo from 1967 until his death in 2005. |

|

Zambia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embassy Park Presidential Burial Site | Lusaka | A national monument that serves as the burial site for the country's deceased presidents, including Levy Mwanawasa, Frederick Chiluba, and Michael Sata.[10] |

|

Zimbabwe

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Heroes' Acre | Harare | A national monument and burial ground administered by the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe. It includes the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. |

|

Asia

[edit]Afghanistan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomb of Ahmad Shah Durrani | Kandahar | The tomb of Ahmad Shah Durrani, the founder of the Durrani Empire. It is one of the most important historical monuments in Afghanistan. |

|

| Mausoleum of Abdur Rahman Khan | Kabul | A mausoleum located in Zarnegar Park in central Kabul, housing the tomb of the Emir of Afghanistan who ruled from 1880 to 1901. |

|

| Bagh-e Babur (Gardens of Babur) | Kabul | The final resting place of the first Mughal emperor, Babur. The garden complex also contains the tombs of other members of his family.[11] |

|

| Mausoleum of Mohammad Zahir Shah | Teppe Maranjan Hill, Kabul | The tomb of Mohammad Zahir Shah, the last King of Afghanistan, who reigned for 40 years. |

|

Armenia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arshakid Mausoleum | Aghdzk | A mausoleum dedicated to the Arsacid kings of Armenia, built in the 4th century. |

|

| Mausoleum of Turkmen Emirs | Argavand | A 15th-century mausoleum dedicated to the emirs of the Kara Koyunlu dynasty. |

|

| Mausoleum of Gregory of Tatev | Tatev Monastery | The tomb of Saint Gregory of Tatev, a 14th-century philosopher, theologian, and saint of the Armenian Apostolic Church. |

|

Azerbaijan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Momine Khatun Mausoleum | Nakhchivan | A 12th-century mausoleum, considered a masterpiece of Nakhchivan architecture. It was commissioned by Atabeg Jahan Pahlavan in honor of his mother. |

|

| Mausoleum of Yusif ibn Kuseyir | Nakhchivan | An octagonal mausoleum built in 1162, another prominent landmark of the Nakhchivan school of architecture. |

|

| Vagif Mausoleum | Shusha | A memorial to Molla Panah Vagif, an 18th-century Azerbaijani poet and vizier of the Karabakh Khanate.[12] |

|

| Nizami Mausoleum | Ganja | A monument built in honor of the 12th-century Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi. |

|

| Mausoleum of Heydar Aliyev | Alley of Honor, Baku | The resting place of Heydar Aliyev, the third President of Azerbaijan. |

|

Bangladesh

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman | Tungipara, Gopalganj | The tomb of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father and first President of Bangladesh. |

|

| Mausoleum of Three Leaders | Suhrawardy Udyan, Dhaka | The burial place of three prominent Bengali political leaders: A. K. Fazlul Huq, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, and Khawaja Nazimuddin. |

|

| Mausoleum of Ziaur Rahman | Chandrima Uddan, Dhaka | The tomb of Ziaur Rahman, the seventh President of Bangladesh. |

|

| Tomb of Shah Jalal | Sylhet | The shrine and tomb of Shah Jalal, a celebrated Sufi saint of Bengal. |

|

Brunei

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Mausoleum (Kubah Makam Diraja) | Bandar Seri Begawan | The final resting place of several Sultans of Brunei and members of the royal family.[13] |

|

| Mausoleum of Sultan Sharif Ali | Kota Batu | The tomb of Sharif Ali, the third Sultan of Brunei and the first to be a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. |

|

| Mausoleum of Sultan Bolkiah | Kota Batu | The tomb of Bolkiah, the fifth Sultan of Brunei, whose reign is considered a golden age in the country's history. |

|

China

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor | Xi'an, Shaanxi | The tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China, famous for being guarded by the Terracotta Army. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[14] |

|

| Ming Dynasty Tombs | Beijing | A collection of mausoleums built by the emperors of the Ming dynasty. This site is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. |

|

| Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum | Nanjing, Jiangsu | The tomb of Sun Yat-sen, the first president of the Republic of China. |

|

| Mausoleum of Mao Zedong | Tiananmen Square, Beijing | The final resting place of Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. |

|

| Mausoleum of Genghis Khan | Ordos City, Inner Mongolia | A cenotaph dedicated to Genghis Khan, where he is worshipped as a deity. His actual burial site remains unknown. |

|

India

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taj Mahal | Agra, Uttar Pradesh | A white marble mausoleum commissioned in 1632 by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan to house the tomb of his favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahal. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[15] |

|

| Humayun's Tomb | Delhi | The tomb of the Mughal Emperor Humayun, commissioned by his first wife, Empress Bega Begum. It was the first garden-tomb on the Indian subcontinent. |

|

| Akbar's tomb | Agra, Uttar Pradesh | The tomb of the Mughal emperor Akbar. Its construction was started by Akbar himself in 1605. |

|

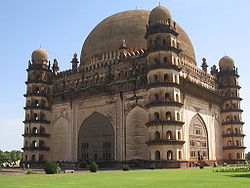

| Gol Gumbaz | Bijapur, Karnataka | The mausoleum of Mohammed Adil Shah, Sultan of Bijapur. It is noted for its massive dome, which is one of the largest in the world. |

|

| Tomb of Sher Shah Suri | Sasaram, Bihar | A mausoleum built in memory of the Pashtun emperor Sher Shah Suri, located in the middle of an artificial lake. |

|

Indonesia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grave of Sukarno (Makam Bung Karno) | Blitar, East Java | The burial site of Sukarno, the first President of Indonesia. |

|

| Astana Giribangun | Karanganyar Regency, Central Java | A mausoleum complex for the family of Suharto, the second President of Indonesia. |

|

| Imogiri | Imogiri, Central Java | A royal cemetery complex for the monarchs of the Mataram Sultanate and their descendants from Yogyakarta and Surakarta. |

|

| Mausoleum O. G. Khouw | Jakarta | A notable mausoleum of a prominent Peranakan Chinese aristocrat, O. G. Khouw. |

|

Iran

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomb of Cyrus the Great | Pasargadae | The final resting place of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. |

|

| Naqsh-e Rustam | Near Persepolis | Contains the rock-cut tombs of Achaemenid kings, including Darius the Great. |

|

| Imam Reza shrine | Mashhad | A vast complex that houses the tomb of the eighth Shia Imam, Ali al-Rida. It is a major pilgrimage site. |

|

| Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini | Tehran | A massive complex housing the tomb of Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran. |

|

| Tomb of Hafez (Hāfezieh) | Shiraz | A memorial hall and tomb dedicated to the celebrated Persian poet Hafez. |

|

Iraq

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imam Ali Shrine | Najaf | According to Shia belief, it contains the tomb of Ali ibn Abi Talib, the first Shia Imam and the fourth Rashidun Caliph. |

|

| Imam Husayn Shrine | Karbala | Houses the tomb of Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. It is one of the holiest sites for Shia Muslims. |

|

| Al-Kadhimiya Mosque | Kadhimiya, Baghdad | Contains the tombs of the seventh and ninth Shia Imams, Musa al-Kadhim and Muhammad al-Jawad. |

|

| Al-Askari Shrine | Samarra | Contains the tombs of the tenth and eleventh Shia Imams, Ali al-Hadi and Hasan al-Askari. |

|

Palestine

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| David's Tomb | Mount Zion, Jerusalem | A site considered by some to be the burial place of David, King of Israel. |

|

| Rachel's Tomb | Bethlehem | Revered as the burial place of the biblical matriarch Rachel. |

|

| Tomb of Samuel | Nabi Samwil | The traditional burial site of the biblical prophet Samuel. |

|

| Yad Avshalom | Kidron Valley, Jerusalem | An ancient monumental tomb, traditionally ascribed to Absalom, the rebellious son of King David. |

|

| Mausoleum of Yasser Arafat | Ramallah | The tomb of Yasser Arafat, former Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and President of the Palestinian National Authority. |

|

Japan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Musashi Imperial Graveyard | Hachiōji, Tokyo | A mausoleum complex which contains the tombs of Emperor Taishō, Empress Teimei, Emperor Shōwa, and Empress Kōjun. |

|

| Nikkō Tōshō-gū | Nikkō, Tochigi Prefecture | A UNESCO World Heritage Site and the final resting place of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. |

|

| Tsuki no wa no misasagi | Sennyū-ji, Kyoto | An imperial mausoleum containing the tombs of numerous Japanese emperors from the 13th to the 19th century. |

|

| Zuihōden | Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture | The mausoleum complex of Date Masamune and his heirs, powerful daimyō of the Sendai Domain. |

|

Jordan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Khazneh (The Treasury) | Petra | An elaborate temple carved out of sandstone, believed to be the mausoleum of the Nabataean King Aretas IV. It is a famous archaeological and tourist site. |

|

| Hashemite Family Cemetery | Amman | The royal cemetery of the Hashemite dynasty, the ruling royal family of Jordan. |

Kazakhstan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi | Turkistan | A monumental, unfinished mausoleum commissioned in 1389 by Timur to honor the Sufi mystic Khoja Ahmed Yasawi. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[16] |

|

| Aisha Bibi Mausoleum | Near Taraz | An 11th or 12th-century mausoleum dedicated to the noblewoman Aisha Bibi, a figure from a local legend. |

|

Kyrgyzstan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uzgen mausoleums | Uzgen | A complex of three mausoleums from the 11th and 12th centuries, built for the rulers of the Kara-Khanid Khanate. |

|

Malaysia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Makam Pahlawan (Heroes' Mausoleum) | National Mosque of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur | The burial ground for several Malaysian leaders and Prime Ministers. |

|

| Mahmoodiah Royal Mausoleum | Johor Bahru, Johor | The royal mausoleum for the Sultans of Johor and their families. |

|

| Al-Ghufran Royal Mausoleum | Kuala Kangsar, Perak | The final resting place for the royal family of Perak. |

|

Mongolia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sükhbaatar's mausoleum | Sükhbaatar Square, Ulaanbaatar | The former mausoleum for Damdin Sükhbaatar, a Mongolian revolutionary leader. His remains were later removed and cremated. |

|

Myanmar

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martyrs' Mausoleum | Yangon | A mausoleum dedicated to Aung San and other leaders of the pre-independence interim government who were assassinated in 1947. |

|

| Kandawmin Garden Mausolea | Yangon | A complex of mausoleums for Queen Supayalat, former UN Secretary-General U Thant, and other notable figures. |

|

| Konbaung tombs | Mandalay | A collection of tombs and mausoleums for the monarchs of the Konbaung dynasty. |

|

Pakistan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mazar-e-Quaid | Karachi | The final resting place of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. |

|

| Tomb of Allama Iqbal | Lahore | The mausoleum of Sir Muhammad Iqbal, the national poet of Pakistan, located in the Hazuri Bagh garden. |

|

| Tomb of Jahangir | Shahdara, Lahore | The 17th-century mausoleum built for the Mughal Emperor Jahangir.[17] |

|

| Data Durbar | Lahore | One of the largest Sufi shrines in South Asia, containing the tomb of the Sufi saint Ali Hujwiri. |

|

| Samadhi of Ranjit Singh | Lahore | A 19th-century mausoleum housing the funerary urns of the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh. |

|

Philippines

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quezon Memorial Circle | Quezon City | A national park and shrine containing the mausoleum of Manuel L. Quezon, the second President of the Philippines, and his wife, Aurora Quezon. |

|

| Aguinaldo Shrine | Kawit, Cavite | The ancestral home of Emilio Aguinaldo, the first President of the Philippines, where his remains are interred. |

|

| Marcos Museum and Mausoleum | Batac | The mausoleum houses the remains of Ferdinand E. Marcos, the tenth President of the Philippines. |

|

| Libingan ng mga Bayani (Cemetery of Heroes) | Taguig, Metro Manila | A national cemetery that houses the remains of Filipino presidents, national heroes, patriots, and soldiers. |

|

Singapore

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keramat Habib Noh | Tanjong Pagar | The mausoleum for Habib Noh, a highly revered 19th-century Sufi saint in Singapore.[18] |

|

| Keramat Iskandar Shah | Fort Canning Hill | The alleged burial place of Iskandar Shah, the last king of Singapura. |

|

South Korea

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty | Various locations | A collection of 40 tombs of members of the Korean Joseon dynasty. The sites are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. |

|

| Seoul National Cemetery | Seoul | A national cemetery that serves as the burial ground for Korean veterans, presidents, and other national figures. |

|

Syria

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umayyad Mosque | Damascus | The mosque is believed to contain the head of John the Baptist. It also houses the shrine of Saladin in an adjacent garden. |

|

| Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque | Damascus | The tomb of Zaynab bint Ali, the granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammad. A major pilgrimage site for Shia Muslims. |

|

| Sayyidah Ruqayya Mosque | Damascus | Contains the tomb of Sukayna bint Husayn (Ruqayya), the youngest daughter of Husayn ibn Ali. |

|

| Nabi Habeel Mosque | Near Zabadani | Believed by some to be the burial place of Abel, son of Adam and Eve. |

|

Taiwan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cihu Presidential Burial Place | Daxi District, Taoyuan | The temporary resting place of Chiang Kai-shek, former President of the Republic of China. |

|

| Touliao Mausoleum | Daxi District, Taoyuan | The temporary resting place of Chiang Ching-kuo, son of Chiang Kai-shek and former President of the Republic of China. |

|

Turkmenistan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Türkmenbaşy Ruhy Mosque | Gypjak, near Ashgabat | A large complex that includes the mausoleum of Saparmurat Niyazov, the first President of Turkmenistan.[19] |

|

| Mausoleum of Il-Arslan | Konye-Urgench | A 12th-century mausoleum, one of the few surviving monuments from the capital of the Khwarazmian Empire. |

|

Turkey

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anıtkabir | Ankara | The mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first President of the Republic of Turkey. It is a site of national pilgrimage.[20] |

|

| Mausoleum at Halicarnassus | Bodrum (ancient Halicarnassus) | The tomb of Mausolus, a satrap in the Persian Empire. It was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and the origin of the word "mausoleum". Only ruins remain today. |

|

| Mevlana Museum | Konya | The mausoleum of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet, Islamic scholar, and Sufi mystic. |

|

| Green Tomb (Yeşil Türbe) | Bursa | The mausoleum of the fifth Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed I. |

|

Uzbekistan

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gur-e-Amir | Samarkand | The mausoleum of the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), the founder of the Timurid Empire. |

|

| Shah-i-Zinda | Samarkand | A necropolis consisting of a series of mausoleums and other ritual buildings from the 9th to 15th centuries. It is believed to contain the tomb of Kusam ibn Abbas, a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad. |

|

| Samanid Mausoleum | Bukhara | The 10th-century resting place of Ismail Samani, a powerful ruler of the Samanid Empire. It is a masterpiece of Central Asian architecture. |

|

Vietnam

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum | Ba Đình Square, Hanoi | The final resting place of Ho Chi Minh, the revolutionary leader and first President of Vietnam. |

|

| Tomb of Tự Đức | Huế | An elegant complex of pavilions, a lake, and the tomb of the Nguyễn Emperor Tự Đức. |

|

| Tomb of Khải Định | Huế | An elaborate mausoleum for the Nguyễn Emperor Khải Định, known for its blend of Vietnamese and European architectural styles. |

|

Europe

[edit]Albania

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of the Albanian Royal Family | Tirana | The resting place of King Zog I, his wife Queen Géraldine, and other members of the Albanian royal family. |

|

Austria

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imperial Crypt (Kaisergruft) | Capuchin Church, Vienna | The principal place of entombment for the members of the House of Habsburg, containing the remains of 12 emperors and 18 empresses.[21] |

|

| Mausoleum of Emperor Ferdinand II | Graz | A monumental tomb complex built in the 17th century for the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II. |

|

Belgium

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of the Counts of Bossu | Boussu | A Renaissance-style chapel mausoleum designed by Jacques Du Brœucq for the Hénin-Liétard family. |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gazi Husrev-beg's Turbe | Sarajevo | The tomb of Gazi Husrev-beg, an Ottoman bey and military strategist who was a key figure in the history of Sarajevo. |

|

| Tomb of Alija Izetbegović | Kovači Cemetery, Sarajevo | The burial site of Alija Izetbegović, the first Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. |

|

Bulgaria

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battenberg Mausoleum | Sofia | The tomb of Prince Alexander I of Battenberg, the first prince of modern Bulgaria. |

|

| St George the Conqueror Chapel Mausoleum | Pleven | A memorial chapel and ossuary built in honor of the soldiers who died during the Siege of Plevna in 1877. |

|

| Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum | Sofia | The former resting place of the first communist leader of Bulgaria, Georgi Dimitrov. The building was demolished in 1999. |

|

Croatia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meštrović family mausoleum | Otavice | The final resting place of the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and his family, a significant work of art in its own right. |

|

| Jelačić family tomb | Zaprešić | The tomb of the influential Jelačić family, including Ban Josip Jelačić. |

|

| Tomb of Franjo Tuđman | Mirogoj Cemetery, Zagreb | The burial site of Franjo Tuđman, the first President of Croatia. |

|

Czech Republic

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Monument in Vítkov | Prague | Originally built as a memorial to the Czechoslovak Legionaries, it later housed the mausoleum of Klement Gottwald, the first communist president of Czechoslovakia. |

|

| Mausoleum of Yugoslavian Soldiers in Olomouc | Olomouc | A mausoleum and ossuary containing the remains of over 1,100 Yugoslav soldiers who died in Austro-Hungarian camps during World War I.[22] |

|

Finland

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juselius Mausoleum | Pori | A neo-Gothic mausoleum built in 1903 by the industrialist Fritz Arthur Jusélius in memory of his daughter Sigrid. It is famous for its original frescoes by Akseli Gallen-Kallela. |

|

France

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Panthéon | Paris | A monumental neoclassical building originally built as a church dedicated to St. Genevieve, it now functions as a secular mausoleum containing the remains of distinguished French citizens such as Voltaire, Rousseau, Victor Hugo, and Marie Curie. |

|

| Les Invalides | Paris | A complex of buildings containing museums and monuments, all relating to the military history of France. It contains the tomb of Napoleon Bonaparte. |

|

| Basilica of Saint-Denis | Saint-Denis, near Paris | A large medieval abbey church that served as the burial site for nearly every French king from the 10th to the 18th centuries. |

|

Germany

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bismarck Mausoleum | Friedrichsruh | The mausoleum of Prince Otto von Bismarck and his wife, Johanna von Puttkamer. |

|

| Mausoleum in the Schlosspark Charlottenburg | Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin | A neoclassical mausoleum that contains the tombs of members of the House of Hohenzollern, including King Frederick William III and Queen Louise.[23] |

|

| The Carstanjen Mausoleum | Bonn | A Grecian rotunda at Haus Carstanjen. |

|

Hungary

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kerepesi Cemetery | Budapest | A major national cemetery with numerous elaborate mausoleums, including those of prominent Hungarian figures like Lajos Kossuth, Ferenc Deák, and Lajos Batthyány. |

|

| Tomb of Gül Baba | Budapest | The tomb of Gül Baba, an Ottoman Bektashi dervish, poet, and companion of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. |

|

Italy

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Augustus | Rome | A large tomb built by the Roman Emperor Augustus in 28 BC for himself and his family. |

|

| Castel Sant'Angelo | Rome | Originally built as a mausoleum for the Roman Emperor Hadrian and his family. It was later used by the popes as a fortress and castle. |

|

| The Pantheon | Rome | An ancient Roman temple, now a church, which serves as the burial place for notable Italians, including the artist Raphael and several Italian kings. |

|

| Mausoleum of Theodoric | Ravenna | An ancient monument built by Theodoric the Great as his future tomb. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[24] |

|

Netherlands

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nieuwe Kerk | Delft | The burial site of the Dutch Royal Family since William the Silent in 1584. |

|

| Mausoleum of Wilhelm II | Huis Doorn, Doorn | The final resting place of the last German Emperor, Wilhelm II. |

|

Poland

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Karol Scheibler's Chapel | Old Cemetery, Łódź | An eclectic, richly decorated mausoleum of the industrialist Karol Scheibler, completed in 1888. |

|

| Powązki Military Cemetery | Warsaw | A military cemetery containing numerous tombs and monuments dedicated to Polish soldiers and national heroes. |

|

Romania

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mausoleum of Mărășești | Mărășești | A memorial dedicated to the Romanian soldiers who fought in World War I, containing the remains of over 5,000 soldiers.[25] |

|

| Tropaeum Traiani | Adamclisi | An ancient Roman monument built in AD 109 in Moesia Inferior, to commemorate Roman Emperor Trajan's victory over the Dacians. |

|

| Mausoleum in Carol Park | Carol Park, Bucharest | Originally built as a mausoleum for communist leaders, it now serves as a memorial for unknown soldiers. |

|

Russia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lenin's Mausoleum | Red Square, Moscow | The final resting place of Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution and first head of the Soviet Union. |

|

| Cathedral of the Archangel | Moscow Kremlin | The burial place of many of Russia's tsars and grand princes from the 14th to the 17th centuries, including Ivan the Terrible. |

|

| Peter and Paul Cathedral | Peter and Paul Fortress, Saint Petersburg | The burial place of most of the Russian emperors and empresses from Peter the Great to Nicholas II and his family. |

|

Serbia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oplenac | Topola | The Church of St. George, also known as Oplenac, is the mausoleum of the Serbian and Yugoslav royal house of Karađorđević. |

|

| Kuća cveća (House of Flowers) | Belgrade | The resting place of Josip Broz Tito, the leader of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. |

|

| Josif Pančić mausoleum | Pančić's Peak | The resting place of Josif Pančić, famed Serbian botanist and academic. |

|

Spain

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| El Escorial | San Lorenzo de El Escorial | A historical residence of the King of Spain. The Royal Crypt serves as the burial site for most of the Spanish monarchs since the 16th century. |

|

| Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen) | San Lorenzo de El Escorial | A monumental complex that includes a basilica and a mausoleum. It was the burial place of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco until 2019. |

|

Ukraine

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nikolay Pirogov's Mausoleum | Vinnytsia | A mausoleum-church where the embalmed body of the renowned scientist and surgeon Nikolay Pirogov is preserved.[26] |

|

United Kingdom

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Mausoleum, Frogmore | Frogmore, Windsor | The mausoleum for Queen Victoria and her consort, Albert, Prince Consort. |

|

| Hamilton Mausoleum | Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, Scotland | A large mausoleum built for Alexander Hamilton, 10th Duke of Hamilton. It is famous for its long-lasting echo. |

|

| Darnley Mausoleum | Kent | An 18th-century mausoleum designed by James Wyatt for the Earls of Darnley. |

|

| Mausoleum of Sir Richard and Lady Burton | Mortlake, London | A unique tomb in the shape of a Bedouin tent, designed by the explorer Richard Francis Burton for himself and his wife, Isabel. |

|

North America

[edit]Canada

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Royal Cemetery | Montreal, Quebec | Features several large, historic mausoleums, including the Molson and Notman family tombs. |

|

| Hart Massey's Mausoleum | Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto | A notable example of Prairie School architecture, designed by Sidney Badgley in 1907 for the prominent Massey family. |

|

Cuba

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Che Guevara Mausoleum | Santa Clara | A memorial complex housing the remains of the Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara and his fellow combatants. |

|

| José Martí Mausoleum | Santa Ifigenia Cemetery, Santiago de Cuba | A large, hexagonal tower serving as the tomb of José Martí, a Cuban national hero and a key figure in Latin American literature. |

|

Mexico

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angel of Independence (El Ángel) | Mexico City | A victory column and monument that also serves as a mausoleum for the heroes of the Mexican War of Independence. |

|

| Monumento a la Revolución | Mexico City | A monument commemorating the Mexican Revolution, which also houses the tombs of several revolutionary heroes, including Pancho Villa. |

|

United States

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grant's Tomb | New York City | The final resting place of Ulysses S. Grant, 18th President of the United States, and his wife, Julia Grant. It is the largest mausoleum in North America.[27] |

|

| Lincoln Tomb | Springfield, Illinois | The state historic site that serves as the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States, his wife, and three of their four sons. |

|

| James A. Garfield Memorial | Cleveland, Ohio | A monumental tomb and memorial for James A. Garfield, 20th President of the United States. |

|

| Stanford Mausoleum | Stanford University, California | The tomb of Leland Stanford, his wife Jane, and their son Leland Stanford Jr., located on the grounds of the university they founded. |

|

South America

[edit]Argentina

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buenos Aires Metropolitan Cathedral | Buenos Aires | Contains the mausoleum of General José de San Martín, one of the primary leaders of South America's struggle for independence. |

|

| La Recoleta Cemetery | Buenos Aires | A famous cemetery known for its numerous elaborate mausoleums, including the tomb of Eva Perón. |

|

| Mausoleum of Néstor Kirchner | Río Gallegos | A large, modern mausoleum for Néstor Kirchner, who was President of Argentina from 2003 to 2007. |

|

Bolivia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Peace | La Paz | Contains the mausoleum of Marshal Andrés de Santa Cruz, who served as President of Peru and Bolivia. |

|

Brazil

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monument to the Independence of Brazil | São Paulo | A monumental complex that includes a crypt and the mausoleum of Emperor Pedro I of Brazil and his two wives. |

|

| Imperial Mausoleum | Cathedral of Petrópolis, Petrópolis | The final resting place of Emperor Pedro II of Brazil and other members of the Brazilian imperial family. |

|

| JK Memorial | Brasília | The burial place of Juscelino Kubitschek, the President of Brazil who was the visionary behind the construction of Brasília. |

|

| Obelisk of São Paulo | São Paulo | A mausoleum dedicated to the students and soldiers killed in the Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932. |

|

Chile

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altar de la Patria | Santiago | A former mausoleum that housed the remains of Bernardo O'Higgins, the founding father of Chile. His remains were later moved to the Crypt of O'Higgins. |

|

Colombia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Cemetery of Bogotá | Bogotá | A large cemetery containing numerous elaborate mausoleums for many former presidents of Colombia and other notable figures. |

|

Paraguay

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Pantheon of the Heroes | Asunción | A national monument and mausoleum housing the remains of many of the country's major historical figures. |

|

Peru

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panteón de los Próceres | Lima | A crypt within the former church of the Real Convictorio de San Carlos that holds the remains of the heroes of the Peruvian War of Independence. |

|

| Presbítero Maestro Cemetery | Lima | A monumental cemetery famous for the large number of elaborate 19th and 20th-century mausoleums. |

|

Uruguay

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artigas Mausoleum | Plaza Independencia, Montevideo | An underground mausoleum dedicated to the national hero José Gervasio Artigas. His remains are kept in an urn in the center.[28] |

|

Venezuela

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Pantheon of Venezuela | Caracas | A former church that was converted into a national pantheon and serves as the final resting place for prominent Venezuelans, including Simón Bolívar. |

|

| Mausoleum of Hugo Chávez | Cuartel de la Montaña, Caracas | The final resting place of Hugo Chávez, who was President of Venezuela from 1999 to 2013. |

|

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrine of Remembrance | Melbourne | Originally built as a memorial to the men and women of Victoria who served in World War I, it now serves as a memorial for all Australians who have served in any war. |

|

| Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier | Australian War Memorial, Canberra | Located in the Hall of Memory, it holds the remains of an unidentified Australian soldier killed on the Western Front in World War I. |

|

New Zealand

[edit]| Mausoleum | Location | Description & Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Massey Memorial | Wellington | The final resting place of William Massey, a former Prime Minister of New Zealand, and his wife. |

|

| Savage Memorial | Bastion Point, Auckland | A memorial and tomb for Michael Joseph Savage, the first Labour Prime Minister of New Zealand. |

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Bénin: Mathieu Kérékou a été enterré dans sa ville natale de Natitingou". RFI (in French). 11 November 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Burundi's ex-president Pierre Nkurunziza is buried". BBC News. 17 July 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Laurent Kabila's Tomb | Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo | Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "Mausoleum, Mosque, Museum & Library | ENKA İnşaat ve Sanayi A.Ş." 2015-02-28. Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "Grand Mosque of Conakry - Islamic center in Conakry, Guinea". aroundus.com. Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ Nasubo, Fred (2023-04-04). "The Place of Jomo Kenyatta's Remains in Contemporary Kenyan Politics - The Elephant". Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "Kamuzu Mausoleum | Lilongwe, Malawi | Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "Monumento aos Heróis Moçambicanos: a história de um povo contada em uma parede". tsevele.co.mz (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "John Garang Mausoleum". Juba in the Making. Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "The occult, the president, and the body". Lusaka Times. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "agh-e Babur". UNESCO world heritage convenvion. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "https://shusha.gov.az/en/abide/vaqifin-meqberesi". shusha.gov.az (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 2025-09-14.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Royal Mausoleum". Brunei Tourism. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Taj Mahal". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Tombs of Jahangir, Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Keramat Habib Noh". Singapore Infopedia. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Saparmurat Niyazov". Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Anıtkabir". Official website of Anıtkabir. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Kaisergruft". Kaisergruft Wien. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Yugoslav Mausoleum". Tourism Olomouc. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Mausoleum". Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Early Christian Monuments of Ravenna". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Vrancea | Vrancea | Wine Region, Mountains, Earthquakes | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "Pirogov Museum". Official website of the Pirogov Museum. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "General Grant National Memorial". National Park Service. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "José Gervasio Artigas". Britannica. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

External links

[edit]Look up list of mausolea in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mausoleums.

List of mausolea

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

A mausoleum is a free-standing, above-ground structure constructed as a tomb to enclose the interred remains of one or more individuals, typically featuring elaborate architecture to serve as a lasting memorial, distinct from simpler underground tombs or crypts integrated into larger edifices.[1][2][3] The term originates from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (near modern Bodrum, Turkey), erected circa 350 BC for Mausolus, satrap of Caria, whose widow Artemisia II commissioned the vast edifice—adorned with sculptures by renowned Greek artists—that epitomized grandeur in funerary design and later inspired the word's adoption into Latin and English.[4][2][5] Such structures proliferated across civilizations, from ancient Persian and Egyptian influences to Renaissance revivals, often embodying cultural, religious, or political symbolism through materials like marble, intricate carvings, and monumental scale.[2][6]

Lists of mausolea catalog these edifices by region, era, or builder, highlighting exemplary cases that reflect evolving burial practices and societal values, such as the Taj Mahal's Mughal opulence or imperial Roman precedents that prioritized eternal commemoration over mere interment.[3][7] They underscore mausolea's role in preserving historical memory, though many face threats from decay, conflict, or neglect, prompting documentation efforts to safeguard architectural legacies amid modern cremation trends and space constraints in urban cemeteries.[8][9]

The Mausoleum of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, known as Bangabandhu, lies in Tungipara, Gopalganj District—his birthplace—commemorating the independence leader who mobilized mass resistance against Pakistani rule, culminating in the 1971 war declaration. Assassinated on 15 August 1975 alongside family members in a military coup, Rahman was reburied here in 1979; the mausoleum complex, designed by architects Ehsan Khan, Ishtiaque Jahir, and Iqbal Habib, includes a reflective pond, museum exhibiting his artifacts, and graves for relatives killed in the attack, drawing annual visits on national mourning days to underscore his role in founding the nation.[164][165] , Khwaja Nazimuddin (died 1964), and Suhrawardy (died 1963), whose advocacy for Bengali autonomy in undivided Bengal laid groundwork for later separatist sentiments leading to 1971. Established in the 1960s adjacent to the site's historic role in Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's 7 March 1971 speech rallying for independence, the domed structure with inscribed plaques highlights their tenures as Bengal's prime ministers under British and Pakistani rule, though their era predates the war itself.[168][169]

Definitions and Classification

Definition and Etymology

A mausoleum constitutes a freestanding, above-ground edifice engineered to permanently enclose and prominently display the remains of deceased persons, typically one or more, serving as a monumental repository distinct from subterranean burials or integrated crypts.[3] This empirical configuration emphasizes durability and visibility, as evidenced by archaeological criteria prioritizing structural integrity for long-term interment and public commemoration. In contemporary applications, the designation extends to communal variants erected within cemeteries, accommodating multiple crypts for collective above-ground entombment to optimize space and accessibility.[10] The nomenclature "mausoleum" derives directly from Mausolus, satrap of Caria under Persian suzerainty circa 377–353 BC, whose eponymous tomb in Halicarnassus established the archetype.[11] Erected by his sister-wife Artemisia II from roughly 353 to 351 BC, the edifice rose to about 40 meters in height on a podium, comprising a rectangular base girded by 36 columns, an entablature with sculptural friezes illustrating Amazonomachy and Centauromachy motifs, a 24-step pyramidal roof, and a crowning quadriga statue.[12] This Hellenistic synthesis of Lycian tomb elevation, Ionian columnar orders, and pyramidal capping influenced posterior sepulchral forms, with Romans generalizing the term for any lavish tomb evoking comparable splendor. Surviving fragments, including frieze panels recovered in the 19th century, substantiate its causal precedence in defining mausolea as ostentatious, externally oriented burial monuments.[13]Architectural and Functional Types

Mausolea are categorized architecturally by their predominant structural forms, which reflect influences from ancient monumental designs adapted for above-ground entombment. Pyramidal types, drawing from Egyptian precedents like the Pyramid of Djoser constructed around 2670 BCE as a royal tomb clad in limestone rising over 200 feet, feature a square base that tapers to an apex, emphasizing verticality and permanence.[14] These forms prioritize geometric solidity, often with minimal internal division to focus on the central sarcophagus. Classical columnar designs, prevalent in revival styles, employ freestanding or engaged columns—such as Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian orders—with capitals supporting entablatures and pediments, evoking temple-like grandeur and symmetry for structural support and aesthetic balance.[15] Domed variants utilize a hemispherical or onion-shaped roof over the chamber, providing expansive overhead coverage while distributing weight through pendentives or squinches, as seen in extensions of Byzantine engineering principles.[16] Modular contemporary forms, akin to cemetery vaults, consist of prefabricated crypt units stacked in grid-like arrays, allowing scalable construction with standardized seals for efficiency in public facilities.[17] Functionally, mausolea differ by interment capacity and purpose: individual units house single remains, typically reserved for rulers or elites in sealed crypts to ensure isolation and veneration, whereas collective types accommodate dynastic lines, families, or groups like war dead through multi-crypt layouts, as in estate or community structures holding unrelated individuals.[10] Durability is engineered via hermetically sealed chambers that isolate contents from soil moisture and atmospheric exposure, maintaining internal dryness and structural integrity over centuries when constructed with quality materials like granite or reinforced concrete.[3] Ventilation features, including manifold pipes or rear-wall vents, facilitate air circulation to mitigate decomposition gases and odors without compromising seals.[18] Anti-theft elements, such as wrought-iron grilles over openings and tamper-resistant crypt lids, deter intrusion while integrating with overall aesthetics.[19] Symbolic components enhance identification and commemoration, with inscriptions etched on facades or interiors recording names, dates, and achievements—often in durable materials like bronze—for posterity. Effigies or sculpted figures, depicting the deceased in reclined repose, convey themes of eternal rest and may adorn sarcophagi or niches, though their use varies by cultural context.[20] These elements, combined with geometric purity or ornamental restraint, underscore the mausoleum's role in preserving legacy against natural decay.[15]Cultural and Religious Perspectives

Perspectives in Abrahamic Faiths

In Judaism, burial practices emphasize simplicity and humility to avoid ostentation and potential idolatry, with traditional law mandating direct interment in the ground without above-ground structures like vaults or mausolea, as these are deemed contrary to core tenets of modesty in death.[21] Exceptions occur in ancient contexts, such as the elaborate tombs attributed to biblical kings like David, whose purported sepulcher on Mount Zion reflects royal precedent rather than normative practice, though modern observance strictly favors unmarked or minimally marked graves to underscore equality in mortality.[22] This doctrinal restraint stems from interpretations of scriptural commands against excessive commemoration, prioritizing spiritual legacy over physical monuments, with internal debates occasionally permitting earth-enclosed mausolea only if the body remains soil-buried.[22] Christian perspectives on mausolea diverge sharply between traditions, with early and Catholic practices endorsing the veneration of saints' tombs and relics as conduits for divine intercession, evidenced by basilica integrations of martyrs' remains from the 4th century onward, such as St. Peter's Basilica over the apostle's grave.[23] This cult, rooted in beliefs of bodily resurrection and miraculous efficacy, fostered elaborate sepulchral architecture across medieval Europe, yet provoked Reformation-era critiques as idolatrous excess, with Protestant reformers like John Calvin decrying relic worship as superstitious deviation from scriptural sola fide, leading to widespread iconoclastic destruction of saintly shrines by the 16th century.[24] Empirical patterns show Catholic continuity in relic-embedded altars and pilgrimage sites, contrasted by Protestant preference for unadorned graves, highlighting ongoing theological tensions over corporeal mediation versus direct divine access.[25] In Islam, prophetic traditions explicitly prohibit erecting structures over graves to avert shirk (associating partners with God), as articulated in hadiths such as Sahih al-Bukhari 1390, where Muhammad curses Jews and Christians for treating prophets' tombs as worship sites, and Sahih Muslim 529, forbidding plastering, building upon, or circumambulating graves.[26] This orthodoxy, emphasizing tawhid (divine unity) and equality in death, mandates leveling graves and bans mausolea, a stance rigorously enforced by Salafi and Wahhabi movements, which demolished sites like those in Saudi Arabia since the 1920s to counter perceived polytheistic drift.[27] Yet empirical divergences persist in Sufi-influenced regions, where folk veneration normalizes domed shrines for awliya (saints) as markers of barakah (blessing), fueling intra-Muslim debates between scriptural literalists viewing such builds as bid'ah (innovation) and cultural practitioners defending them as non-worshipful remembrance, though orthodox sources consistently deem the latter as erosion of prophetic intent.[26]Perspectives in Eastern and Indigenous Traditions

In Hindu tradition, samadhi shrines serve as memorials for enlightened ascetics who achieve moksha, marking the burial site of their physical remains as a locus of enduring spiritual presence rather than mere interment. These structures, derived from the yogic concept of samadhi as a state of meditative absorption, embody the belief that the guru's realized consciousness persists, facilitating devotees' access to transformative energy through pilgrimage and ritual.[28][29] Unlike standard cremation practices, burial in samadhi preserves the body intact to honor this continuity, as seen in sites dedicated to figures like Ramana Maharshi, whose 1950 samadhi at Arunachaleswara Temple draws ongoing veneration.[30] Buddhist stupas, originating as hemispherical mounds over the Buddha's relics circa 5th century BCE, function as symbolic repositories of enlightenment rather than tombs focused on individual decay. Encasing sarira (relics) or mantras, they represent the five elements and the path to nirvana, promoting spiritual purification and communal circumambulation for merit accumulation.[31][32] The Great Stupa at Sanchi, constructed around 3rd century BCE under Emperor Ashoka, exemplifies this, housing relics that sustain the sangha's connection to Shakyamuni Buddha's legacy.[33] Confucian-influenced Chinese imperial mausolea, such as the Ming Tombs complex near Beijing initiated in 1409 CE, underscore filial piety (xiao) and dynastic legitimacy via the Mandate of Heaven, wherein rulers' eternal repose affirmed cosmic harmony and ancestral oversight of successors. These vast complexes, often spanning thousands of acres with spirit ways and sacrificial altars, integrated geomancy (feng shui) to channel qi for posthumous influence, reinforcing social order through ritual maintenance by descendants.[34][35] Indigenous traditions worldwide emphasize mausolea-like structures for collective ancestral continuity, integrating burials into landscapes to preserve communal identity and ecological bonds. North American mound builders, active from circa 1000 BCE to 1500 CE, constructed earthen tumuli like Cahokia's Monk's Mound (built around 900-1100 CE) as platforms for elite interments and ceremonies, embedding remains with grave goods to invoke forebears' guidance in tribal governance and agriculture.[36][37] Similarly, Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings in the American Southwest, such as Mesa Verde's circa 600-1300 CE sites, housed communal tombs within architectural ensembles, fostering rituals that linked living kin to ancestral spirits for resource stewardship and social cohesion.[38]Secular and Political Uses

In the 20th century, secular mausolea emerged as instruments of state propaganda, particularly in authoritarian regimes, where the embalmed remains of leaders were enshrined in glass sarcophagi to evoke perpetual guidance and ideological continuity. Vladimir Lenin's Mausoleum in Moscow, constructed after his death on January 21, 1924, and opened to the public on August 1, 1924, set a precedent by displaying his preserved body adjacent to the Kremlin, linking the leader's legacy directly to governmental authority.[39] This approach symbolized an "eternal rule," detaching veneration from religious eschatology and instead serving to legitimize successor regimes through ritualized visitation.[40] The practice proliferated among hard-left governments, with Mao Zedong's body embalmed following his death on September 9, 1976, and placed in the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, completed and opened on the same date in 1977. Similar displays include Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi and the Kims in North Korea's Kumsusan Palace of the Sun, where embalming techniques, often Soviet-assisted, preserved bodies for public viewing to reinforce narratives of undiminished leadership influence.[41] These mausolea functioned as sites for controlled pilgrimages, where queues of visitors—over 100,000 in the initial weeks for Lenin's temporary display—underwent security checks and silence mandates, embedding state ideology through experiential deference.[42] Critics argue that such edifices cultivate personality cults, prioritizing symbolic immortality over practical governance, as evidenced by ongoing preservation debates in Russia, where a 2017 poll indicated 58% public support for Lenin's burial, suggesting imposed rather than organic reverence.[43] Resource allocation for maintenance, including specialized embalming and climate control, diverts funds from socioeconomic needs, with analysts noting that the propagandistic value—measured by visitor metrics often amplified by state organization—fails to yield verifiable causal benefits for regime stability amid declining ideological adherence.[44] Empirical data on attendance, while touted by authorities as indicators of loyalty, reflect logistical mobilization more than voluntary endorsement, underscoring the causal primacy of coercion in sustaining these displays.[45]Historical Development

Ancient Origins (Pre-Common Era)

The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, constructed circa 2630–2610 BCE during Egypt's Third Dynasty, represents one of the earliest monumental tombs functioning as a proto-mausoleum for Pharaoh Djoser. Built by architect Imhotep, it evolved from earlier flat-topped mastaba tombs into a six-tiered stepped structure over 60 meters tall, enclosing a burial chamber and ritual spaces to facilitate the king's ascent to the afterlife amid solar and stellar alignments. Succeeding Old Kingdom pyramids, such as the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza (circa 2580–2560 BCE), amplified this funerary architecture with smooth-sided forms reaching 146 meters in height, precise cardinal orientations, and internal features like granite sarcophagi and passages potentially aligned to celestial bodies for the pharaoh's eternal voyage. These edifices, quarried from millions of limestone blocks by corvée labor, embodied the ruler's semi-divine status and included protective inscriptions akin to curses deterring desecration, as evidenced by quarry marks and king lists correlating to archaeological strata.[46] In Mesopotamia, the Royal Cemetery at Ur uncovered circa 2600–2300 BCE pit tombs for Sumerian elites, including deep shafts lined with chambers containing gold-inlaid artifacts, musical instruments, and remains of sacrificed attendants—up to 74 in one burial—signaling precursors to mausolea through their emphasis on ruler veneration and communal sacrifice. Excavated by Leonard Woolley from 1922–1934, sites like Queen Puabi's tomb (PG 800) yielded cylinder seals and lapis lazuli headdresses, confirming elite status via stratigraphic dating and artifact typology tied to the Early Dynastic period.[47][48] Etruscan tumuli, emerging from the 9th century BCE in central Italy, featured earthen mounds over rock-hewn chamber tombs at necropolises like Banditaccia near Cerveteri, spanning Villanovan to Hellenistic phases until the 3rd century BCE. These hypogeal structures replicated living quarters with benches, frescoes, and sarcophagi for family groups, as revealed by continuous occupation layers and imported goods, prioritizing afterlife continuity for aristocrats in a non-pharaonic tradition.[49][50] The Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huangdi, initiated circa 246 BCE and completed by 210 BCE in modern Xi'an, China, scaled absolutism to unprecedented levels with an underground palace complex spanning 56 square kilometers, guarded by over 8,000 terracotta soldiers, horses, and chariots molded individually. Commanding 700,000 laborers including convicts and artisans, this pre-imperial endeavor—predating the emperor's unification in 221 BCE—mirrored his realm in mercury rivers and celestial models, per Sima Qian's records corroborated by pit excavations since 1974.[51][52]Medieval and Early Modern Periods

In the medieval period, mausolea proliferated in the Islamic world, often integrated into multifunctional complexes that combined funerary, educational, and religious functions, reflecting the era's emphasis on patronage of learning alongside commemoration. During the Seljuk and subsequent Timurid eras, structures like the mausoleum of Shajarat al-Durr in Cairo (1250), attached to a madrasa, set precedents for urban sultanate tombs blending scholarship and burial.[53] The Timurid Gawhar Shad complex in Herat (1417–1438) exemplified this, incorporating a madrasa, mosque, and mausoleum to honor the patroness while advancing theological education.[54] These designs underscored causal ties to feudal expansions, where rulers commissioned enduring monuments to legitimize dynastic authority amid fragmented polities. The Crusades (1095–1291) spurred architectural cross-pollination, introducing European builders to Islamic pointed arches and domes, which influenced Gothic funerary chapels and effigial tombs in churches.[55] In feudal Europe, standalone mausolea remained rare; instead, royal and noble burials occurred within abbeys and cathedrals, such as Westminster Abbey's role as a Plantagenet mausoleum from the 14th century, featuring elaborate effigies symbolizing hierarchical continuity.[56] Reading Abbey, founded by Henry I in 1121 as his burial site, similarly served feudal lords, integrating tombs into monastic settings to invoke spiritual intercession.[57] Transitioning to the early modern period, Renaissance innovations revived classical forms in mausolea, merging pagan iconography—such as Michelangelo's allegorical figures—with Christian eschatology in the Medici Chapels' New Sacristy (1520–1534), Florence, a ducal tomb emphasizing humanistic resurrection themes.[58] Absolutist regimes amplified this grandeur to project divine-right permanence; Philip II's El Escorial (1563–1584), Spain, functioned as monastery, palace, and Habsburg pantheon, its austere granite facade embodying centralized monarchical power.[59] In Ottoman and Mughal domains, expansive domes over mausolea evoked cosmic harmony and imperial eternity, aligning with absolutist cosmologies. Ottoman complexes, like those in the Süleymaniye Mosque (1550–1557), Istanbul, housed sultanic tombs under vaults symbolizing tawhid (divine unity). but avoid wiki; from [web:21]. Mughal Humayun's Tomb, Delhi (1569–1572), pioneered garden-mausolea with a double dome representing celestial order, influencing successors like the Taj Mahal.[60][61] These structures causally linked to absolutism by visually subordinating the ruler's legacy to universal hierarchies, deterring feudal fragmentation through architectural permanence.Industrial and Contemporary Era

The Industrial Era marked a shift in mausoleum design through the integration of mass-produced materials enabled by advancing manufacturing techniques, particularly in Victorian garden cemeteries established across Europe and North America from the 1830s onward. These landscaped burial grounds, such as London's Brompton Cemetery opened in 1840, incorporated ornate cast-iron elements like crypt doors and structural components, leveraging the durability and affordability of iron cast via industrial foundries.[62] In the United States, similar innovations appeared in cemeteries like those in New Orleans, where at least eight cast-iron mausolea, produced using prefabricated panels, were constructed in the mid-19th century to withstand humid conditions and reflect emerging industrial aesthetics.[63] Cast iron's use extended to grave vaults and fences in sites like Alabama's Victorian-era cemeteries, where it prevented soil erosion while allowing intricate, machine-replicated ornamentation.[64] Nationalism further propelled monumental mausolea as symbols of state unity and military heroism during the late 19th century. A prominent example is Grant's Tomb in New York City, completed on April 27, 1897, and designed by architect John Duncan in a neoclassical style using granite and marble; at 150 feet tall, it remains North America's largest mausoleum, enshrining Civil War general Ulysses S. Grant and his wife Julia as emblems of post-war reconciliation.[65] Such structures emphasized grandeur and permanence, often funded through public subscriptions to foster collective identity amid rapid urbanization and imperial expansion. In the 20th century, totalitarian regimes elevated mausolea to ideological shrines, incorporating scientific preservation methods for leaders' bodies to sustain cults of personality. Vladimir Lenin's Mausoleum in Moscow featured an initial wooden structure erected in 1924 following his January death, replaced by a permanent granite edifice completed in 1930 under architect Alexei Shchusev, where his embalmed corpse—maintained through ongoing chemical treatments and climate control—has been displayed continuously.[66][67] This model influenced similar facilities, such as those for Josip Broz Tito in Belgrade's House of Flowers mausoleum, dedicated in 1982 after his 1980 death, blending modernist architecture with preserved remains to symbolize regime continuity.[68] These sites prioritized reinforced concrete and state-orchestrated engineering over traditional materials, reflecting mass mobilization of resources for propaganda. Post-2000 developments have introduced limited experimentation with eco-mausolea using sustainable materials like recycled composites or low-impact concrete, though such designs remain rare and mostly confined to experimental green cemeteries rather than grand structures. Traditional mausolea continue to dominate contemporary national commemorations, often adapting industrial-era prefabrication for efficiency in politically symbolic burials.[69]Controversies and Destructions

Religious Iconoclasm and Theological Debates

In certain interpretations of Islamic theology, particularly those emphasizing strict monotheism (tawhid), the construction and veneration of mausolea over graves constitute shirk (associating partners with God) or bid'ah (innovation forbidden by prophetic tradition), prompting deliberate destructions justified by scriptural prohibitions such as hadiths warning against building structures on graves or turning them into places of worship.[70][71] These acts stem from a causal chain rooted in core texts like Sahih al-Bukhari, which records the Prophet Muhammad's leveling of graves and condemnation of their exaltation, viewed by adherents as a direct mandate to eradicate perceived idolatry rather than arbitrary violence.[72] In Timbuktu, Mali, Ansar Dine militants demolished at least 14 mausolea of Sufi saints in June-July 2012, explicitly targeting structures they deemed idolatrous under their enforcement of puritanical Islam, which aligns with fatwas against saint veneration as antithetical to tawhid.[73][70] Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, a key figure in these attacks, was convicted by the International Criminal Court in 2016 for the war crime of intentionally directing assaults on religious and historical buildings, receiving a nine-year sentence; his plea acknowledged participation but framed the motive as religious purification, underscoring the clash between theological imperatives and international legal norms that prioritize cultural preservation over doctrinal conformity.[74][75] Wahhabi authorities in Saudi Arabia leveled domes and mausolea in the Al-Baqi' Cemetery in Medina during 1925 and April 1926, following fatwas from local clerics prohibiting grave adornment and visitation rituals as forms of shirk, with the demolitions executed under orders to enforce hadith-based simplicity in burial practices.[76] This event, affecting sites associated with early Islamic figures including companions of the Prophet, reflected a consistent Salafi-Wahhabi stance against any elevation of graves that could foster superstition, as articulated in rulings by scholars like Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab.[77] The Islamic State (ISIS) similarly destroyed the Tomb of Jonah in Mosul, Iraq, in July 2014, and ancient shrines near Palmyra, Syria, in June 2015, invoking hadiths against tomb veneration as shirk and framing the acts as fulfilling prophetic commands to prevent polytheistic practices, thereby prioritizing scriptural literalism over archaeological value.[78][79] These destructions, often documented in ISIS propaganda as religious duties, illustrate a pattern where theological debates over grave sanctity—rooted in Sunni hadith traditions rejecting Sufi intercession—drive iconoclasm, independent of broader political strategies.[72]Political and Ideological Desecrations

In the aftermath of revolutions and regime shifts, mausolea housing remains of former rulers or ideologues frequently become targets for state-sponsored desecration, serving as symbolic acts to delegitimize predecessors and consolidate new power structures. Such actions often follow patterns observed across 20th-century upheavals, where successor regimes prioritize erasure of monarchical or authoritarian legacies to prevent veneration that could inspire counter-movements; for instance, post-1917 Bolshevik campaigns and post-1989 Eastern European transitions saw systematic targeting of imperial and communist burial sites, with over 70% of communist-era monuments in Poland and Hungary removed or altered by 2000 according to regional heritage inventories.[80] These desecrations typically involve looting for resources, structural demolition, or repurposing, driven by ideological rejection rather than mere neglect. A prominent example occurred in China during the chaotic warlord period of the Northern Expedition. In June 1928, forces under warlord Sun Dianying dynamited entrances to the Eastern Qing Tombs near Zunhua, Hebei, looting the underground palaces of Emperor Qianlong and Empress Dowager Cixi; artifacts removed included Cixi's three pearl-encrusted gold-thread quilts, jade burial suits, and thousands of jewels valued at millions in contemporary silver dollars, ostensibly to finance military operations amid factional strife.[81][82] This raid, executed under pretext of military drills, inflicted irreversible damage—such as water ingress from breached seals—exemplifying how power vacuums enable ideological opportunism, where Qing imperial symbols were plundered to sustain anti-republican warlords rather than purely revolutionary zeal. In post-communist Eastern Europe, similar motives drove assaults on mausolea tied to Soviet-aligned figures. Bulgaria's government targeted the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum in Sofia, completed in 1949 to house the embalmed body of the communist leader who died in 1949; after his remains were reburied in a cemetery in 1990 amid decommunization, four demolition attempts commenced on August 21, 1999, using 600 kg of explosives in initial blasts that failed to fully collapse the 1.5-meter-thick granite structure, necessitating mechanical excavation to complete razing by August 27.[83][84] The effort, costing approximately 1 million leva (about $500,000 USD at the time), symbolized a broader anti-communist purge, though technical failures highlighted the durability of such edifices built for permanence. The Soviet experience illustrates ironic reversals in these patterns. Early Bolshevik desecrations targeted tsarist mausolea, such as vandalizing sarcophagi in St. Petersburg's Peter and Paul Cathedral during 1918-1922 anti-religious campaigns, where imperial tombs were opened, relics dispersed, and sites repurposed to dismantle Romanov legitimacy; yet, by the 1930s, the regime preserved select structures like the fortress itself as museums for propaganda, while erecting and maintaining Lenin's Mausoleum on Red Square since 1924 as an embalmed ideological counter-symbol, revealing pragmatic preservation amid revolutionary iconoclasm to avoid total historical void. This duality—initial destruction followed by selective conservation—mirrors data from post-revolutionary contexts, where 40-60% of elite mausolea in transitioning states are altered within a decade, per analyses of 20th-century case studies.[85]Modern Threats from Development and Neglect