Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

History of India

View on Wikipedia

| History of India |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

Anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago.[1] The earliest known human remains in South Asia date to 30,000 years ago. Sedentariness began in South Asia around 7000 BCE; by 4500 BCE, settled life had spread,[2] and gradually evolved into the Indus Valley Civilisation, one of three early cradles of civilisation in the Old World,[3][4] which flourished between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE in present-day Pakistan and north-western India. Early in the second millennium BCE, persistent drought caused the population of the Indus Valley to scatter from large urban centres to villages. Indo-Aryan tribes moved into the Punjab from Central Asia in several waves of migration. The Vedic Period of the Vedic people in northern India (1500–500 BCE) was marked by the composition of their extensive collections of hymns (Vedas). The social structure was loosely stratified via the varna system, incorporated into the highly evolved present-day Jāti system. The pastoral and nomadic Indo-Aryans spread from the Punjab into the Gangetic plain. Around 600 BCE, a new, interregional culture arose; then, small chieftaincies (janapadas) were consolidated into larger states (mahajanapadas). Second urbanization took place, which came with the rise of new ascetic movements and religious concepts,[5] including the rise of Jainism and Buddhism. The latter was synthesized with the preexisting religious cultures of the subcontinent, giving rise to Hinduism.

Chandragupta Maurya overthrew the Nanda Empire and established the first great empire in ancient India, the Maurya Empire. India's Mauryan king Ashoka is widely recognised for the violent kalinga war and his historical acceptance of Buddhism and his attempts to spread nonviolence and peace across his empire. The Maurya Empire would collapse in 185 BCE, on the assassination of the then-emperor Brihadratha by his general Pushyamitra Shunga. Shunga would form the Shunga Empire in the north and north-east of the subcontinent, while the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom would claim the north-west and found the Indo-Greek Kingdom. Various parts of India were ruled by numerous dynasties, including the Gupta Empire, in the 4th to 6th centuries CE. This period, witnessing a Hindu religious and intellectual resurgence is known as the Classical or Golden Age of India. Aspects of Indian civilisation, administration, culture, and religion spread to much of Asia, which led to the establishment of Indianised kingdoms in the region, forming Greater India.[6][5] The most significant event between the 7th and 11th centuries was the Tripartite struggle centred on Kannauj. Southern India saw the rise of multiple imperial powers from the middle of the fifth century. The Chola dynasty conquered southern India in the 11th century. In the early medieval period, Indian mathematics, including Hindu numerals, influenced the development of mathematics and astronomy in the Arab world, including the creation of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system.[7]

Islamic conquests made limited inroads into modern Afghanistan and Sindh as early as the 8th century,[8] followed by the invasions of Mahmud Ghazni.[9] The Delhi Sultanate, established in 1206 by Central Asian Turks, ruled much of northern India in the 14th century. It was governed by various Turkic and Afghan dynasties, including the Indo-Turkic Tughlaqs.[10][11] The empire declined in the late 14th century following the invasions of Timur[12] and saw the advent of the Malwa, Gujarat, and Bahmani sultanates, the last of which split in 1518 into the five Deccan sultanates. The wealthy Bengal Sultanate also emerged as a major power, lasting over three centuries.[13] During this period, multiple strong Hindu kingdoms, notably the Vijayanagara Empire and Rajput states under the Kingdom of Mewar emerged and played significant roles in shaping the cultural and political landscape of India.[14][15]

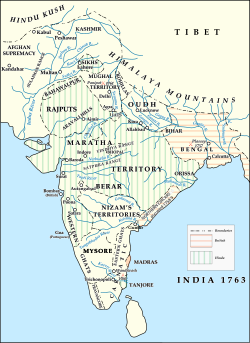

The early modern period began in the 16th century, when the Mughal Empire conquered most of the Indian subcontinent,[16] signaling the proto-industrialisation, becoming the biggest global economy and manufacturing power.[17][18][19] The Mughals suffered a gradual decline in the early 18th century, largely due to the rising power of the Marathas, who took control of extensive regions of the Indian subcontinent, and numerous Afghan invasions.[20][21][22] The East India Company, acting as a sovereign force on behalf of the British government, gradually acquired control of huge areas of India between the middle of the 18th and the middle of the 19th centuries. Policies of company rule in India led to the Indian Rebellion of 1857. India was afterwards ruled directly by the British Crown, in the British Raj. After World War I, a nationwide struggle for independence was launched by the Indian National Congress, led by Mahatma Gandhi. Later, the All-India Muslim League would advocate for a separate Muslim-majority nation state. The British Indian Empire was partitioned in August 1947 into the Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan, each gaining its independence.

Prehistoric era (before c. 3300 BCE)

[edit]This section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (July 2021) |

Paleolithic

[edit]Hominin expansion from Africa is estimated to have reached the Indian subcontinent approximately two million years ago, and possibly as early as 2.2 million years ago.[26][27][28] This dating is based on the known presence of Homo erectus in Indonesia by 1.8 million years ago and in East Asia by 1.36 million years ago, as well as the discovery of stone tools at Riwat in Pakistan.[27][29] Although some older discoveries have been claimed, the suggested dates, based on the dating of fluvial sediments, have not been independently verified.[28][30]

The oldest hominin fossil remains in the Indian subcontinent are those of Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis, from the Narmada Valley in central India, and are dated to approximately half a million years ago.[27][30] Older fossil finds have been claimed, but are considered unreliable.[30] Reviews of archaeological evidence have suggested that occupation of the Indian subcontinent by hominins was sporadic until approximately 700,000 years ago, and was geographically widespread by approximately 250,000 years ago.[30][28]

According to a historical demographer of South Asia, Tim Dyson:

Modern human beings—Homo sapiens—originated in Africa. Then, intermittently, sometime between 60,000 and 80,000 years ago, tiny groups of them began to enter the north-west of the Indian subcontinent. It seems likely that initially they came by way of the coast. It is virtually certain that there were Homo sapiens in the subcontinent 55,000 years ago, even though the earliest fossils that have been found of them date to only about 30,000 years before the present.[31]

According to Michael D. Petraglia and Bridget Allchin:

Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonisation of South Asia by modern humans originating in Africa. ... Coalescence dates for most non-European populations average to between 73–55 ka.[32]

Historian of South Asia, Michael H. Fisher, states:

Scholars estimate that the first successful expansion of the Homo sapiens range beyond Africa and across the Arabian Peninsula occurred from as early as 80,000 years ago to as late as 40,000 years ago, although there may have been prior unsuccessful emigrations. Some of their descendants extended the human range ever further in each generation, spreading into each habitable land they encountered. One human channel was along the warm and productive coastal lands of the Persian Gulf and northern Indian Ocean. Eventually, various bands entered India between 75,000 years ago and 35,000 years ago.[33]

Archaeological evidence has been interpreted to suggest the presence of anatomically modern humans in the Indian subcontinent 78,000–74,000 years ago,[34] although this interpretation is disputed.[35][36] The occupation of South Asia by modern humans, initially in varying forms of isolation as hunter-gatherers, has turned it into a highly diverse one, second only to Africa in human genetic diversity.[37]

According to Tim Dyson:

Genetic research has contributed to knowledge of the prehistory of the subcontinent's people in other respects. In particular, the level of genetic diversity in the region is extremely high. Indeed, only Africa's population is genetically more diverse. Related to this, there is strong evidence of 'founder' events in the subcontinent. By this is meant circumstances where a subgroup—such as a tribe—derives from a tiny number of 'original' individuals. Further, compared to most world regions, the subcontinent's people are relatively distinct in having practised comparatively high levels of endogamy.[37]

Neolithic

[edit]

Settled life emerged on the subcontinent in the western margins of the Indus River alluvium approximately 9,000 years ago, evolving gradually into the Indus Valley Civilisation of the third millennium BCE.[2][39] According to Tim Dyson: "By 7,000 years ago agriculture was firmly established in Baluchistan... [and] slowly spread eastwards into the Indus valley." Michael Fisher adds:[40]

The earliest discovered instance ... of well-established, settled agricultural society is at Mehrgarh in the hills between the Bolan Pass and the Indus plain (today in Pakistan) (see Map 3.1). From as early as 7000 BCE, communities there started investing increased labor in preparing the land and selecting, planting, tending, and harvesting particular grain-producing plants. They also domesticated animals, including sheep, goats, pigs, and oxen (both humped zebu [Bos indicus] and unhumped [Bos taurus]). Castrating oxen, for instance, turned them from mainly meat sources into domesticated draft-animals as well.[40]

Bronze Age (c. 3300 – 1800 BCE)

[edit]Indus Valley Civilisation

[edit]

The Bronze Age in the Indian subcontinent began around 3300 BCE.[citation needed] The Indus Valley region was one of three early cradles of civilisation in the Old World; the Indus Valley civilisation was the most expansive,[3] and at its peak, may have had a population of over five million.[4]

The civilisation was primarily centred in modern-day Pakistan, in the Indus river basin, and secondarily in the Ghaggar-Hakra River basin. The mature Indus civilisation flourished from about 2600 to 1900 BCE, marking the beginning of urban civilisation on the Indian subcontinent. It included cities such as Harappa, Ganweriwal, and Mohenjo-daro in modern-day Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, and Lothal in modern-day India.

Inhabitants of the ancient Indus River valley, the Harappans, developed new techniques in metallurgy and handicraft, and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin.[42] The civilisation is noted for its cities built of brick, and its roadside drainage systems, and is thought to have had some kind of municipal organisation. The civilisation also developed an Indus script, the earliest of the ancient Indian scripts, which is presently undeciphered.[43] This is the reason why Harappan language is not directly attested, and its affiliation is uncertain.[44]

After the collapse of Indus Valley civilisation, the inhabitants migrated from the river valleys of Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra, towards the Himalayan foothills of Ganga-Yamuna basin.[45]

Ochre Coloured Pottery culture

[edit]

During the 2nd millennium BCE, Ochre Coloured Pottery culture was in Ganga Yamuna Doab region. These were rural settlements with agriculture and hunting. They were using copper tools such as axes, spears, arrows, and swords, and had domesticated animals.[47]

Iron Age (c. 1800 – 200 BCE)

[edit]Vedic period (c. 1500 – 600 BCE)

[edit]Starting c. 1900 BCE, Indo-Aryan tribes moved into the Punjab from Central Asia in several waves of migration.[48][49] The Vedic period is when the Vedas were composed of liturgical hymns from the Indo-Aryan people. The Vedic culture was located in part of north-west India, while other parts of India had a distinct cultural identity. Many regions of the Indian subcontinent transitioned from the Chalcolithic to the Iron Age in this period.[50]

The Vedic culture is described in the texts of Vedas, still sacred to Hindus, which were orally composed and transmitted in Vedic Sanskrit. The Vedas are some of the oldest extant texts in India.[51] The Vedic period, lasting from about 1500 to 500 BCE,[52][53] contributed to the foundations of several cultural aspects of the Indian subcontinent.

Vedic society

[edit]

Historians have analysed the Vedas to posit a Vedic culture in the Punjab, and the upper Gangetic Plain.[50] The Peepal tree and cow were sanctified by the time of the Atharva Veda.[55] Many of the concepts of Indian philosophy espoused later, like dharma, trace their roots to Vedic antecedents.[56]

Early Vedic society is described in the Rigveda, the oldest Vedic text, believed to have been compiled during the 2nd millennium BCE,[57][58] in the north-western region of the Indian subcontinent.[59] At this time, Aryan society consisted of predominantly tribal and pastoral groups, distinct from the Harappan urbanisation which had been abandoned.[60] The early Indo-Aryan presence probably corresponds, in part, to the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture in archaeological contexts.[61][62]

At the end of the Rigvedic period, the Aryan society expanded from the north-western region of the Indian subcontinent into the western Ganges plain. It became increasingly agricultural and was socially organised around the hierarchy of the four varnas, or social classes.[63] This social structure was characterised by the exclusion of some indigenous peoples by labelling their occupations impure.[64] During this period, many of the previous small tribal units and chiefdoms began to coalesce into Janapadas (monarchical, state-level polities).[65]

Sanskrit epics

[edit]

The Sanskrit epics Ramayana and Mahabharata were composed during this period.[66] The Mahabharata remains the longest single poem in the world.[67] Historians formerly postulated an "epic age" as the milieu of these two epic poems, but now recognise that the texts went through multiple stages of development over centuries.[68] The existing texts of these epics are believed to belong to the post-Vedic age, between c. 400 BCE and 400 CE.[68][69]

Janapadas

[edit]

The Iron Age in the Indian subcontinent from about 1200 BCE to the 6th century BCE is defined by the rise of Janapadas, which are realms, republics and kingdoms—notably the Iron Age Kingdoms of Kuru, Panchala, Kosala and Videha.[70][71]

The Kuru Kingdom (c. 1200–450 BCE) was the first state-level society of the Vedic period, corresponding to the beginning of the Iron Age in north-western India, around 1200–800 BCE,[72] as well as with the composition of the Atharvaveda.[73] The Kuru state organised the Vedic hymns into collections and developed the srauta ritual to uphold the social order.[73] Two key figures of the Kuru state were king Parikshit and his successor Janamejaya, who transformed this realm into the dominant political, social, and cultural power of northern India.[73] When the Kuru kingdom declined, the centre of Vedic culture shifted to their eastern neighbours, the Panchala kingdom.[73] The archaeological PGW (Painted Grey Ware) culture, which flourished in north-eastern India's Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh regions from about 1100 to 600 BCE,[61] is believed to correspond to the Kuru and Panchala kingdoms.[73][74]

During the Late Vedic Period, the kingdom of Videha emerged as a new centre of Vedic culture, situated even farther to the East (in what is today Nepal and Bihar state);[62] reaching its prominence under the king Janaka, whose court provided patronage for Brahmin sages and philosophers such as Yajnavalkya, Aruni, and Gārgī Vāchaknavī.[75] The later part of this period corresponds with a consolidation of increasingly large states and kingdoms, called Mahajanapadas, across Northern India.

Second urbanisation (c. 600 – 200 BCE)

[edit]

The period between 800 and 200 BCE saw the formation of the Śramaṇa movement, from which Jainism and Buddhism originated. The first Upanishads were written during this period. After 500 BCE, the so-called "second urbanisation"[note 1] started, with new urban settlements arising at the Ganges plain.[77] The foundations for the "second urbanisation" were laid prior to 600 BCE, in the Painted Grey Ware culture of the Ghaggar-Hakra and Upper Ganges Plain; although most PGW sites were small farming villages, "several dozen" PGW sites eventually emerged as relatively large settlements that can be characterised as towns, the largest of which were fortified by ditches or moats and embankments made of piled earth with wooden palisades.[78]

The Central Ganges Plain, where Magadha gained prominence, forming the base of the Maurya Empire, was a distinct cultural area,[79] with new states arising after 500 BCE.[80][81] It was influenced by the Vedic culture,[82] but differed markedly from the Kuru-Panchala region.[83] It "was the area of the earliest known cultivation of rice in South Asia and by 1800 BCE was the location of an advanced Neolithic population associated with the sites of Chirand and Chechar".[84] In this region, the Śramaṇic movements flourished, and Jainism and Buddhism originated.[74]

Buddhism and Jainism

[edit]The time between 800 BCE and 400 BCE witnessed the composition of the earliest Upanishads,[85][86][87] which form the theoretical basis of classical Hinduism, and are also known as the Vedanta (conclusion of the Vedas).[88]

The increasing urbanisation of India in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE led to the rise of new ascetic or "Śramaṇa movements" which challenged the orthodoxy of rituals.[85] Mahavira (c. 599–527 BCE), proponent of Jainism, and Gautama Buddha (c. 563–483 BCE), founder of Buddhism, were the most prominent icons of this movement. Śramaṇa gave rise to the concept of the cycle of birth and death, the concept of samsara, and the concept of liberation.[89] Buddha found a Middle Way that ameliorated the extreme asceticism found in the Śramaṇa religions.[90]

Around the same time, Mahavira (the 24th Tirthankara in Jainism) propagated a theology that was to later become Jainism.[91] However, Jain orthodoxy believes the teachings of the Tirthankaras predates all known time and scholars believe Parshvanatha (c. 872 – c. 772 BCE), accorded status as the 23rd Tirthankara, was a historical figure. The Vedas are believed to have documented a few Tirthankaras and an ascetic order similar to the Śramaṇa movement.[92]

Mahajanapadas

[edit]

The period from c. 600 BCE to c. 300 BCE featured the rise of the Mahajanapadas, sixteen powerful kingdoms and oligarchic republics in a belt stretching from Gandhara in the north-west to Bengal in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent—including parts of the trans-Vindhyan region.[93] Ancient Buddhist texts, like the Aṅguttara Nikāya,[94] make frequent reference to these sixteen great kingdoms and republics—Anga, Assaka, Avanti, Chedi, Gandhara, Kashi, Kamboja, Kosala, Kuru, Magadha, Malla, Matsya (or Machcha), Panchala, Surasena, Vṛji, and Vatsa. This period saw the second major rise of urbanism in India after the Indus Valley Civilisation.[95]

Early "republics" or gaṇasaṅgha,[96] such as Shakyas, Koliyas, Mallakas, and Licchavis had republican governments. Gaṇasaṅghas,[96] such as the Mallakas, centered in the city of Kusinagara, and the Vajjika League, centred in the city of Vaishali, existed as early as the 6th century BCE and persisted in some areas until the 4th century CE.[97] The most famous clan amongst the ruling confederate clans of the Vajji Mahajanapada were the Licchavis.[98]

This period corresponds in an archaeological context to the Northern Black Polished Ware culture. Especially focused in the Central Ganges plain but also spreading across vast areas of the northern and central Indian subcontinent, this culture is characterised by the emergence of large cities with massive fortifications, significant population growth, increased social stratification, wide-ranging trade networks, construction of public architecture and water channels, specialised craft industries, a system of weights, punch-marked coins, and the introduction of writing in the form of Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts.[99][100] The language of the gentry at that time was Sanskrit, while the languages of the general population of northern India are referred to as Prakrits.

Many of the sixteen kingdoms had merged into four major ones by the time of Gautama Buddha. These four were Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala, and Magadha.[95]

Early Magadha dynasties

[edit]

Magadha formed one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas (Sanskrit: "Great Realms") or kingdoms in ancient India. The core of the kingdom was the area of Bihar south of the Ganges; its first capital was Rajagriha (modern Rajgir) then Pataliputra (modern Patna). Magadha expanded to include most of Bihar and Bengal with the conquest of Licchavi and Anga respectively,[101] followed by much of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Orissa. The ancient kingdom of Magadha is heavily mentioned in Jain and Buddhist texts. It is also mentioned in the Ramayana, Mahabharata and Puranas.[102] The earliest reference to the Magadha people occurs in the Atharva-Veda where they are found listed along with the Angas, Gandharis, and Mujavats. Magadha played an important role in the development of Jainism and Buddhism. Republican communities (such as the community of Rajakumara) are merged into Magadha kingdom. Villages had their own assemblies under their local chiefs called Gramakas. Their administrations were divided into executive, judicial, and military functions.

Early sources, from the Buddhist Pāli Canon, the Jain Agamas and the Hindu Puranas, mention Magadha being ruled by the Pradyota dynasty and Haryanka dynasty (c. 544–413 BCE) for some 200 years, c. 600–413 BCE. King Bimbisara of the Haryanka dynasty led an active and expansive policy, conquering Anga in what is now eastern Bihar and West Bengal. King Bimbisara was overthrown and killed by his son, Prince Ajatashatru, who continued the expansionist policy of Magadha. During this period, Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, lived much of his life in the Magadha kingdom. He attained enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, gave his first sermon in Sarnath and the first Buddhist council was held in Rajgriha.[103] The Haryanka dynasty was overthrown by the Shaishunaga dynasty (c. 413–345 BCE). The last Shishunaga ruler, Kalasoka, was assassinated by Mahapadma Nanda in 345 BCE, the first of the so-called Nine Nandas (Mahapadma Nanda and his eight sons).

Nanda Empire and Alexander's campaign

[edit]The Nanda Empire (c. 345–322 BCE), at its peak, extended from Bengal in the east, to the Punjab in the west and as far south as the Vindhya Range.[104] The Nanda dynasty built on the foundations laid by their Haryanka and Shishunaga predecessors.[105] Nanda empire have built a vast army, consisting of 200,000 infantry, 20,000 cavalry, 2,000 war chariots and 3,000 war elephants (at the lowest estimates).[106][107]

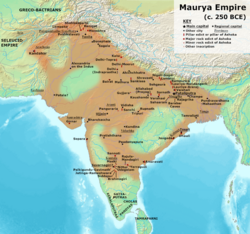

Maurya Empire

[edit]The Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE) unified most of the Indian subcontinent into one state, and was the largest empire ever to exist on the Indian subcontinent.[108] At its greatest extent, the Mauryan Empire stretched to the north up to the natural boundaries of the Himalayas and to the east into what is now Assam. To the west, it reached beyond modern Pakistan, to the Hindu Kush mountains in what is now Afghanistan. The empire was established by Chandragupta Maurya assisted by Chanakya (Kautilya) in Magadha (in modern Bihar) when he overthrew the Nanda Empire.[109]

Chandragupta rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India, and by 317 BCE the empire had fully occupied north-western India. The Mauryan Empire defeated Seleucus I, founder of the Seleucid Empire, during the Seleucid–Mauryan war, thus gained additional territory west of the Indus River. Chandragupta's son Bindusara succeeded to the throne around 297 BCE. By the time he died in c. 272 BCE, a large part of the Indian subcontinent was under Mauryan suzerainty. However, the region of Kalinga (around modern day Odisha) remained outside Mauryan control, perhaps interfering with trade with the south.[110]

Bindusara was succeeded by Ashoka, whose reign lasted until his death in about 232 BCE.[111] His campaign against the Kalingans in about 260 BCE, though successful, led to immense loss of life and misery. This led Ashoka to shun violence, and subsequently to embrace Buddhism.[110] The empire began to decline after his death and the last Mauryan ruler, Brihadratha, was assassinated by Pushyamitra Shunga to establish the Shunga Empire.[111]

Under Chandragupta Maurya and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single efficient system of finance, administration, and security. The Mauryans built the Grand Trunk Road, one of Asia's oldest and longest major roads connecting the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia.[112] After the Kalinga War, the Empire experienced nearly half a century of peace and security under Ashoka. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of scientific knowledge. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of Jainism increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism has been said to have been the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across India.[citation needed] Ashoka sponsored Buddhist missions across the Indo-Mediterranean, into Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West Asia, North Africa, and Mediterranean Europe.[113]

The Arthashastra written by Chanakya and the Edicts of Ashoka are the primary written records of the Mauryan times. Archaeologically, this period falls in the era of Northern Black Polished Ware. The Mauryan Empire was based on a modern and efficient economy and society in which the sale of merchandise was closely regulated by the government.[114] Although there was no banking in the Mauryan society, usury was customary. A significant amount of written records on slavery are found, suggesting a prevalence thereof.[115] During this period, a high-quality steel called Wootz steel was developed in south India and was later exported to China and Arabia.[116]

Sangam period

[edit]During the Sangam period Tamil literature flourished from the 3rd century BCE to the 4th century CE. Three Tamil dynasties, collectively known as the Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam: Chera dynasty, Chola dynasty, and the Pandya dynasty ruled parts of southern India.[118]

The Sangam literature deals with the history, politics, wars, and culture of the Tamil people of this period.[119] Unlike Sanskrit writers who were mostly Brahmins, Sangam writers came from diverse classes and social backgrounds and were mostly non-Brahmins.[120]

Around c. 300 BCE – c. 200 CE, Pathupattu, an anthology of ten mid-length book collections, which is considered part of Sangam Literature, were composed; the composition of eight anthologies of poetic works Ettuthogai as well as the composition of eighteen minor poetic works Patiṉeṇkīḻkaṇakku; while Tolkāppiyam, the earliest grammarian work in the Tamil language was developed.[121] Also, during Sangam period, two of the Five Great Epics of Tamil Literature were composed. Ilango Adigal composed Silappatikaram, which is a non-religious work, that revolves around Kannagi,[122] and Manimekalai, composed by Chithalai Chathanar, is a sequel to Silappatikaram, and tells the story of the daughter of Kovalan and Madhavi, who became a Buddhist Bhikkhuni.[123][124]

Classical period (c. 200 BCE – 650 CE)

[edit]-

Ancient India during the rise of the Shunga Empire from the North, Satavahana dynasty from the Deccan, and Pandyan dynasty and Chola dynasty from the southern part of India.

-

Great Chaitya in the Karla Caves. The shrines were developed over the period from the 2nd century BCE to the 5th century CE.

-

Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves is home to the Hathigumpha inscription, which was inscribed under Kharavela, then Emperor of Kalinga of the Mahameghavahana dynasty.

The time between the Maurya Empire in the 3rd century BCE and the end of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century CE is referred to as the "Classical" period of India.[127] The Gupta Empire (4th–6th century) is regarded as the Golden Age of India, although a host of kingdoms ruled over India in these centuries. Also, the Sangam literature flourished from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE in southern India.[128] During this period, India's economy is estimated to have been the largest in the world, having between one-third and one-quarter of the world's wealth, from 1 CE to 1000 CE.[129][130]

Early classical period (c. 200 BCE – 320 CE)

[edit]Shunga Empire

[edit]The Shungas originated from Magadha, and controlled large areas of the central and eastern Indian subcontinent from around 187 to 78 BCE. The dynasty was established by Pushyamitra Shunga, who overthrew the last Maurya emperor. Its capital was Pataliputra, but later emperors, such as Bhagabhadra, also held court at Vidisha, modern Besnagar.[131]

Pushyamitra Shunga ruled for 36 years and was succeeded by his son Agnimitra. There were ten Shunga rulers. However, after the death of Agnimitra, the empire rapidly disintegrated;[132] inscriptions and coins indicate that much of northern and central India consisted of small kingdoms and city-states that were independent of any Shunga hegemony.[133] The empire is noted for its numerous wars with both foreign and indigenous powers. They fought with the Mahameghavahana dynasty of Kalinga, Satavahana dynasty of Deccan, the Indo-Greeks, and possibly the Panchalas and Mitras of Mathura.

Art, education, philosophy, and other forms of learning flowered during this period including architectural monuments such as the Stupa at Bharhut and the renowned Great Stupa at Sanchi. The Shunga rulers helped to establish the tradition of royal sponsorship of learning and art. The script used by the empire was a variant of Brahmi and was used to write the Sanskrit language. The Shunga Empire played an imperative role in patronising Indian culture at a time when some of the most important developments in Hindu thought were taking place.

Satavahana Empire

[edit]The Śātavāhanas were based from Amaravati in Andhra Pradesh as well as Junnar (Pune) and Prathisthan (Paithan) in Maharashtra. The territory of the empire covered large parts of India from the 1st century BCE onward. The Sātavāhanas started out as feudatories to the Mauryan dynasty, but declared independence with its decline.

The Sātavāhanas are known for their patronage of Hinduism and Buddhism, which resulted in Buddhist monuments from Ellora (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) to Amaravati. They were one of the first Indian states to issue coins with their rulers embossed. They formed a cultural bridge and played a vital role in trade as well as the transfer of ideas and culture to and from the Indo-Gangetic Plain to the southern tip of India.

They had to compete with the Shunga Empire and then the Kanva dynasty of Magadha to establish their rule. Later, they played a crucial role to protect large part of India against foreign invaders like the Sakas, Yavanas and Pahlavas. In particular, their struggles with the Western Kshatrapas went on for a long time. The notable rulers of the Satavahana Dynasty Gautamiputra Satakarni and Sri Yajna Sātakarni were able to defeat the foreign invaders like the Western Kshatrapas and to stop their expansion. In the 3rd century CE, the empire was split into smaller states.[134]

Trade and travels to India

[edit]

The spice trade in Kerala attracted traders from all over the Old World to India. India's Southwest coastal port Muziris had established itself as a major spice trade centre from as early as 3,000 BCE, according to Sumerian records. Jewish traders arrived in Kochi, Kerala, India as early as 562 BCE.[135] The Greco-Roman world followed by trading along the incense route and the Roman-India routes.[136] During the 2nd century BCE Greek and Indian ships met to trade at Arabian ports such as Aden.[137] During the first millennium, the sea routes to India were controlled by the Indians and Ethiopians that became the maritime trading power of the Red Sea.

Indian merchants involved in spice trade took Indian cuisine to Southeast Asia, where spice mixtures and curries became popular with the native inhabitants.[138] Buddhism entered China through the Silk Road in the 1st or 2nd century CE.[139] Hindu and Buddhist religious establishments of South and Southeast Asia came to be centres of production and commerce as they accumulated capital donated by patrons. They engaged in estate management, craftsmanship, and trade. Buddhism in particular travelled alongside the maritime trade, promoting literacy, art, and the use of coinage.[140]

Kushan Empire

[edit]The Kushan Empire expanded out of what is now Afghanistan into the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under the leadership of their first emperor, Kujula Kadphises, about the middle of the 1st century CE. The Kushans were possibly a Tocharian speaking tribe,[141] one of five branches of the Yuezhi confederation.[142][143] By the time of his grandson, Kanishka the Great, the empire spread to encompass much of Afghanistan,[144] and then the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.[145]

Emperor Kanishka was a great patron of Buddhism; however, as Kushans expanded southward, the deities of their later coinage came to reflect its new Hindu majority.[146][147] Historian Vincent Smith said about Kanishka:

He played the part of a second Ashoka in the history of Buddhism.[148]

The empire linked the Indian Ocean maritime trade with the commerce of the Silk Road through the Indus valley, encouraging long-distance trade, particularly between China and Rome. The Kushans brought new trends to the budding and blossoming Gandhara art and Mathura art, which reached its peak during Kushan rule.[149] The period of peace under Kushan rule is known as Pax Kushana. By the 3rd century, their empire in India was disintegrating and their last known great emperor was Vasudeva I.[150][151]

Classical period (c. 320 – 650 CE)

[edit]Gupta Empire

[edit]The Gupta period was noted for cultural creativity, especially in literature, architecture, sculpture, and painting.[152] The Gupta period produced scholars such as Kalidasa, Aryabhata, Varahamihira, Vishnu Sharma, and Vatsyayana. The Gupta period marked a watershed of Indian culture: the Guptas performed Vedic sacrifices to legitimise their rule, but they also patronised Buddhism, an alternative to Brahmanical orthodoxy. The military exploits of the first three rulers – Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, and Chandragupta II – brought much of India under their leadership.[153] Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era. Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural centre and established it as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions.[154][155] The period of peace under Gupta rule is known as Pax Gupta.

The latter Guptas successfully resisted the northwestern kingdoms until the arrival of the Alchon Huns, who established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century CE, with their capital at Bamiyan.[156] However, much of the southern India including Deccan were largely unaffected by these events.[157][158]

Vakataka Empire

[edit]The Vākāṭaka Empire originated from the Deccan in the mid-third century CE. Their state is believed to have extended from the southern edges of Malwa and Gujarat in the north to the Tungabhadra River in the south as well as from the Arabian Sea in the western to the edges of Chhattisgarh in the east. They were the most important successors of the Satavahanas in the Deccan, contemporaneous with the Guptas in northern India and succeeded by the Vishnukundina dynasty.

The Vakatakas are noted for having been patrons of the arts, architecture and literature. The rock-cut Buddhist viharas and chaityas of Ajanta Caves (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) were built under the patronage of Vakataka emperor, Harishena.[159][160]

-

Buddhist monks praying in front of the Dagoba of Chaitya Cave 26 of the Ajanta Caves.

-

Buddhist "Chaitya Griha" or prayer hall, with a seated Buddha, Cave 26 of the Ajanta Caves.

-

Many foreign ambassadors, representatives, and travelers are included as devotees attending the Buddha's descent from Trayastrimsa Heaven; painting from Cave 17 of the Ajanta Caves.

Kamarupa Kingdom

[edit]

Samudragupta's 4th-century Allahabad pillar inscription mentions Kamarupa (Western Assam)[161] and Davaka (Central Assam)[162] as frontier kingdoms of the Gupta Empire. Davaka was later absorbed by Kamarupa, which grew into a large kingdom that spanned from Karatoya river to near present Sadiya and covered the entire Brahmaputra valley, North Bengal, parts of Bangladesh and, at times Purnea and parts of West Bengal.[163]

Ruled by three dynasties Varmanas (c. 350–650 CE), Mlechchha dynasty (c. 655–900 CE) and Kamarupa-Palas (c. 900–1100 CE), from their capitals in present-day Guwahati (Pragjyotishpura), Tezpur (Haruppeswara) and North Gauhati (Durjaya) respectively. All three dynasties claimed their descent from Narakasura.[citation needed] In the reign of the Varman king, Bhaskar Varman (c. 600–650 CE), the Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited the region and recorded his travels. Later, after weakening and disintegration (after the Kamarupa-Palas), the Kamarupa tradition was somewhat extended until c. 1255 CE by the Lunar I (c. 1120–1185 CE) and Lunar II (c. 1155–1255 CE) dynasties.[164] The Kamarupa kingdom came to an end in the middle of the 13th century when the Khen dynasty under Sandhya of Kamarupanagara (North Guwahati), moved his capital to Kamatapur (North Bengal) after the invasion of Muslim Turks, and established the Kamata kingdom.[165]

Pallava Empire

[edit]

The Pallavas, during the 4th to 9th centuries were, alongside the Guptas of the North, great patronisers of Sanskrit development in the South of the Indian subcontinent. The Pallava reign saw the first Sanskrit inscriptions in a script called Grantha.[166] Early Pallavas had different connexions to Southeast Asian countries. The Pallavas used Dravidian architecture to build some very important Hindu temples and academies in Mamallapuram, Kanchipuram and other places; their rule saw the rise of great poets. The practice of dedicating temples to different deities came into vogue followed by fine artistic temple architecture and sculpture style of Vastu Shastra.[167]

Pallavas reached the height of power during the reign of Mahendravarman I (571–630 CE) and Narasimhavarman I (630–668 CE) and dominated the Telugu and northern parts of the Tamil region until the end of the 9th century.[168]

Kadamba Empire

[edit]

Kadambas originated from Karnataka, was founded by Mayurasharma in 345 CE which at later times showed the potential of developing into imperial proportions. King Mayurasharma defeated the armies of Pallavas of Kanchi possibly with help of some native tribes. The Kadamba fame reached its peak during the rule of Kakusthavarma, a notable ruler with whom the kings of Gupta Dynasty of northern India cultivated marital alliances. The Kadambas were contemporaries of the Western Ganga Dynasty and together they formed the earliest native kingdoms to rule the land with absolute autonomy. The dynasty later continued to rule as a feudatory of larger Kannada empires, the Chalukya and the Rashtrakuta empires, for over five hundred years during which time they branched into minor dynasties (Kadambas of Goa, Kadambas of Halasi and Kadambas of Hangal).

Empire of Harsha

[edit]Harsha ruled northern India from 606 to 647 CE. He was the son of Prabhakarvardhana and the younger brother of Rajyavardhana, who were members of the Vardhana dynasty and ruled Thanesar, in present-day Haryana.

After the downfall of the prior Gupta Empire in the middle of the 6th century, North India reverted to smaller republics and monarchical states. The power vacuum resulted in the rise of the Vardhanas of Thanesar, who began uniting the republics and monarchies from the Punjab to central India. After the death of Harsha's father and brother, representatives of the empire crowned Harsha emperor in April 606 CE, giving him the title of Maharaja.[170] At the peak, his Empire covered much of North and Northwestern India, extended East until Kamarupa, and South until Narmada River; and eventually made Kannauj (in present Uttar Pradesh) his capital, and ruled until 647 CE.[171]

The peace and prosperity that prevailed made his court a centre of cosmopolitanism, attracting scholars, artists and religious visitors.[171] During this time, Harsha converted to Buddhism from Surya worship.[172] The Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited the court of Harsha and wrote a very favourable account of him, praising his justice and generosity.[171] His biography Harshacharita ("Deeds of Harsha") written by Sanskrit poet Banabhatta, describes his association with Thanesar and the palace with a two-storied Dhavalagriha (White Mansion).[173][174]

Early medieval period (c. 650 – 1200)

[edit]Early medieval India began after the end of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century CE.[127] This period also covers the "Late Classical Age" of Hinduism, which began after the collapse of the Empire of Harsha in the 7th century,[175] and ended in the 13th century with the rise of the Delhi Sultanate in Northern India;[176] the beginning of Imperial Kannauj, leading to the Tripartite struggle; and the end of the Later Cholas with the death of Rajendra Chola III in 1279 in Southern India; however some aspects of the Classical period continued until the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in the south around the 17th century.

From the fifth century to the thirteenth, Śrauta sacrifices declined, and support for Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Shaktism expanded in royal courts, while the support for Buddhism declined.[177] Lack of appeal among the rural masses, who instead embraced Brahmanical Hinduism formed in the Hindu synthesis, and dwindling financial support from trading communities and royal elites, were major factors in the decline of Buddhism.[178]

In the 7th century, Kumārila Bhaṭṭa formulated his school of Mimamsa philosophy and defended the position on Vedic rituals.[179]

From the 8th to the 10th century, three dynasties contested for control of northern India: the Gurjara Pratiharas of Malwa, the Palas of Bengal, and the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan. The Sena dynasty would later assume control of the Pala Empire; the Gurjara Pratiharas fragmented into various states, notably the Kingdom of Malwa, the Kingdom of Bundelkhand, the Kingdom of Dahala, the Tomaras of Haryana, and the Kingdom of Sambhar, these states were some of the earliest Rajput kingdoms;[180] while the Rashtrakutas were annexed by the Western Chalukyas.[181] During this period, the Chaulukya dynasty emerged; the Chaulukyas constructed the Dilwara Temples, Modhera Sun Temple, Rani ki vav[182] in the style of Māru-Gurjara architecture, and their capital Anhilwara (modern Patan, Gujarat) was one of the largest cities in the Indian subcontinent, with the population estimated at 100,000 in c. 1000. Patan's rise also marked the revival of Jainism in Gujarat during the times of Hemchandracharya. It became renowned for its collection of ancient Jain manuscripts and an important centre of Jain learning,[183] which drew the admiration of many scholars. British Indologist and Sanskritist Peter Peterson described the collection as follows:

I know of no town in India and only a few in the world which can boast of so great a store documents of venerable antiquity. They would be the pride and jealously guarded treasure of any University Library in Europe.[184]

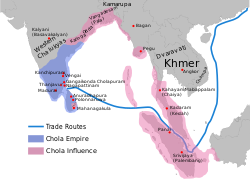

The Chola Empire emerged as a major power during the reign of Raja Raja Chola I and Rajendra Chola I who successfully invaded parts of Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka in the 11th century.[185] Lalitaditya Muktapida (r. 724–760) was an emperor of the Kashmiri Karkoṭa dynasty, which exercised influence in northwestern India from 625 until 1003, and was followed by Lohara dynasty. Kalhana in his Rajatarangini credits king Lalitaditya with leading an aggressive military campaign in Northern India and Central Asia.[186][187][188]

The Hindu Shahi dynasty ruled portions of eastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and Kashmir from the mid-7th century to the early 11th century. While in Odisha, the Eastern Ganga Empire rose to power; noted for the advancement of Hindu architecture, most notable being Jagannath Temple and Konark Sun Temple, as well as being patrons of art and literature.

-

Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya, and built by the third ruler of the Karkota dynasty, Lalitaditya Muktapida, in the 8th century

-

Konark Sun Temple at Konark, Orissa, built by Narasimhadeva I (1238–1264) of the Eastern Ganga dynasty

Later Gupta dynasty

[edit]

The Later Gupta dynasty ruled the Magadha region in eastern India between the 6th and 7th centuries AD. The Later Guptas succeeded the imperial Guptas as the rulers of Magadha, but there is no evidence connecting the two dynasties; these appear to be two distinct families.[189] The Later Guptas are so-called because the names of their rulers ended with the suffix "-gupta", which they might have adopted to portray themselves as the legitimate successors of the imperial Guptas.[190]

Chalukya Empire

[edit]The Chalukya Empire ruled large parts of southern and central India between the 6th and the 12th centuries, as three related yet individual dynasties. The earliest dynasty, known as the "Badami Chalukyas", ruled from Vatapi (modern Badami) from the middle of the 6th century. The Badami Chalukyas began to assert their independence at the decline of the Kadamba kingdom of Banavasi and rapidly rose to prominence during the reign of Pulakeshin II. The rule of the Chalukyas marks an important milestone in the history of South India and a golden age in the history of Karnataka. The political atmosphere in South India shifted from smaller kingdoms to large empires with the ascendancy of Badami Chalukyas. A Southern India-based kingdom took control and consolidated the entire region between the Kaveri and the Narmada Rivers. The rise of this empire saw the birth of efficient administration, overseas trade and commerce and the development of new style of architecture called "Chalukyan architecture". The Chalukya dynasty ruled parts of southern and central India from Badami in Karnataka between 550 and 750, and then again from Kalyani between 970 and 1190.

-

Galaganatha Temple at Pattadakal complex (UNESCO World Heritage) is an example of Badami Chalukya architecture

-

8th century Durga temple exterior view at Aihole complex. It includes Hindu, Buddhist and Jain temples and monuments

Rashtrakuta Empire

[edit]Founded by Dantidurga around 753,[191] the Rashtrakuta Empire ruled from its capital at Manyakheta for almost two centuries.[192] At its peak, the Rashtrakutas ruled from the Ganges-Yamuna Doab in the north to Cape Comorin in the south, a fruitful time of architectural and literary achievements.[193][194]

The early rulers of this dynasty were Hindu, but the later rulers were strongly influenced by Jainism.[195] Govinda III and Amoghavarsha were the most famous of the long line of able administrators produced by the dynasty. Amoghavarsha was also an author and wrote Kavirajamarga, the earliest known Kannada work on poetics.[192][196] Architecture reached a milestone in the Dravidian style, the finest example of which is seen in the Kailasanath Temple at Ellora. Other important contributions are the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal in Karnataka.

The Arab traveller Suleiman described the Rashtrakuta Empire as one of the four great Empires of the world.[197] The Rashtrakuta period marked the beginning of the golden age of southern Indian mathematics. The great south Indian mathematician Mahāvīra had a huge impact on medieval south Indian mathematicians.[198] The Rashtrakuta rulers also patronised men of letters in a variety of languages.[192]

Gurjara-Pratihara Empire

[edit]The Gurjara-Pratiharas were instrumental in containing Arab armies moving east of the Indus River. Nagabhata I defeated the Arab army under Junaid and Tamin during the Umayyad campaigns in India.[199] Under Nagabhata II, the Gurjara-Pratiharas became the most powerful dynasty in northern India. He was succeeded by his son Ramabhadra, who ruled briefly before being succeeded by his son, Mihira Bhoja. Under Bhoja and his successor Mahendrapala I, the Pratihara Empire reached its peak of prosperity and power. By the time of Mahendrapala, its territory stretched from the border of Sindh in the west to Bihar in the east and from the Himalayas in the north to around the Narmada River in the south.[200] The expansion triggered a tripartite power struggle with the Rashtrakuta and Pala empires for control of the Indian subcontinent.

By the end of the 10th century, several feudatories of the empire took advantage of the temporary weakness of the Gurjara-Pratiharas to declare their independence, notably the Kingdom of Malwa, the Kingdom of Bundelkhand, the Tomaras of Haryana, and the Kingdom of Sambhar[201] and the Kingdom of Dahala.[citation needed]

-

Sculptures near Teli ka Mandir, Gwalior Fort

-

Jainism-related cave monuments and statues carved into the rock face inside Siddhachal Caves, Gwalior Fort

-

Ghateshwara Mahadeva temple at Baroli Temples complex. Complex of eight temples, built by the Gurjara-Pratiharas, within a walled enclosure

Gahadavala dynasty

[edit]Gahadavala dynasty ruled parts of the present-day Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, during 11th and 12th centuries. Their capital was located at Varanasi.[203]

Karnat dynasty

[edit]

In 1097 AD, the Karnat dynasty of Mithila emerged on the Bihar/Nepal border area and maintained capitals in Darbhanga and Simraongadh. The dynasty was established by Nanyadeva, a military commander of Karnataka origin. Under this dynasty, the Maithili language started to develop with the first piece of Maithili literature, the Varna Ratnakara being produced in the 14th century by Jyotirishwar Thakur. The Karnats also carried out raids into Nepal. They fell in 1324 following the invasion of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq.[204][205]

Pala Empire

[edit]

The Pala Empire was founded by Gopala I.[206][207][208] It was ruled by a Buddhist dynasty from Bengal. The Palas reunified Bengal after the fall of Shashanka's Gauda Kingdom.[209]

The Palas were followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism,[210] they also patronised Shaivism and Vaishnavism.[211] The empire reached its peak under Dharmapala and Devapala. Dharmapala is believed to have conquered Kanauj and extended his sway up to the farthest limits of India in the north-west.[211]

The Pala Empire can be considered as the golden era of Bengal.[212] Dharmapala founded the Vikramashila and revived Nalanda,[211] considered one of the first great universities in recorded history. Nalanda reached its height under the patronage of the Pala Empire.[212][213] The Palas also built many viharas. They maintained close cultural and commercial ties with countries of Southeast Asia and Tibet. Sea trade added greatly to the prosperity of the Pala Empire.

Cholas

[edit]

Medieval Cholas rose to prominence during the middle of the 9th century and established the greatest empire South India had seen.[214] They successfully united the South India under their rule and through their naval strength extended their influence in the Southeast Asian countries such as Srivijaya.[185] Under Rajaraja Chola I and his successors Rajendra Chola I, Rajadhiraja Chola, Virarajendra Chola and Kulothunga Chola I the dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in South Asia and South-East Asia.[215][216] Rajendra Chola I's navies occupied the sea coasts from Burma to Vietnam,[217] the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Lakshadweep (Laccadive) islands, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula. The power of the new empire was proclaimed to the eastern world by the expedition to the Ganges which Rajendra Chola I undertook and by the occupation of cities of the maritime empire of Srivijaya in Southeast Asia, as well as by the repeated embassies to China.[218]

They dominated the political affairs of Sri Lanka for over two centuries through repeated invasions and occupation. They also had continuing trade contacts with the Arabs and the Chinese empire.[219] Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I gave political unity to the whole of Southern India and established the Chola Empire as a respected sea power.[220] Under the Cholas, the South India reached new heights of excellence in art, religion and literature. In all of these spheres, the Chola period marked the culmination of movements that had begun in an earlier age under the Pallavas. Monumental architecture in the form of majestic temples and sculpture in stone and bronze reached a finesse never before achieved in India.[221]

-

The granite gopuram (tower) of Brihadeeswarar Temple, 1010

-

Chariot detail at Airavatesvara Temple built by Rajaraja Chola II in the 12th century

-

The pyramidal structure above the sanctum at Brihadisvara Temple.

-

Brihadeeswara Temple Entrance Gopurams at Thanjavur

Western Chalukya Empire

[edit]The Western Chalukya Empire ruled most of the western Deccan, South India, between the 10th and 12th centuries.[223] Vast areas between the Narmada River in the north and Kaveri River in the south came under Chalukya control.[223] During this period the other major ruling families of the Deccan, the Hoysalas, the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, the Kakatiya dynasty and the Southern Kalachuris, were subordinates of the Western Chalukyas and gained their independence only when the power of the Chalukya waned during the latter half of the 12th century.[224]

The Western Chalukyas developed an architectural style known today as a transitional style, an architectural link between the style of the early Chalukya dynasty and that of the later Hoysala empire. Most of its monuments are in the districts bordering the Tungabhadra River in central Karnataka. Well known examples are the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi, the Mallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti, the Kallesvara Temple at Bagali, Siddhesvara Temple at Haveri, and the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi.[225] This was an important period in the development of fine arts in Southern India, especially in literature as the Western Chalukya kings encouraged writers in the native language of Kannada, and Sanskrit like the philosopher and statesman Basava and the great mathematician Bhāskara II.[226][227]

-

Ornate entrance to the closed hall from the south at Kalleshvara Temple at Bagali

-

Shrine wall relief, molding frieze and miniature decorative tower in Mallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti

-

Rear view showing lateral entrances of the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi

Late medieval period (c. 1200 – 1526)

[edit]The late medieval period is marked by repeated invasions by Muslim Central Asian nomadic clans,[228][229] the rule of the Delhi Sultanate, and by the growth of other states, built upon military technology of the sultanate.[230]

Delhi Sultanate

[edit]The Delhi Sultanate was a series of successive Islamic states based in Delhi, ruled by several dynasties of varying origins. The polity ruled over large parts of the Indian subcontinent from the 13th to early 16th centuries.[231] The sultanate was founded in the 12th and 13th centuries by Central Asian Turks, who invaded parts of northern India and established the state atop former Hindu holdings.[232] The subsequent Mamluk dynasty of Delhi managed to conquer large areas of northern India. The Khalji dynasty conquered much of central India while forcing the principal Hindu kingdoms of South India to become vassal states.[231]

The sultanate ushered in a period of Indian cultural renaissance. The resulting "Indo-Muslim" fusion of cultures left lasting syncretic monuments in architecture, music, literature, religion, and clothing. It is surmised that the language of Urdu was born during the period of the Delhi Sultanate. The sultanate was the only Indo-Islamic state to enthrone one of the few female rulers in India, Razia Sultana (r. 1236–1240).

While initially disruptive due to the passing of power from native Indian elites to Turkic Muslim elites, the Delhi Sultanate was responsible for integrating the Indian subcontinent into a growing world system, drawing India into a wider international network, which had a significant impact on Indian culture and society.[233] However, the Delhi Sultanate also caused large-scale destruction and desecration of temples in the Indian subcontinent.[234]

The Mongol invasions of India were successfully repelled by the Delhi Sultanate during the rule of Alauddin Khalji. A major factor in their success was their Turkic Mamluk slave army, who were highly skilled in the same style of nomadic cavalry warfare as the Mongols. It is possible that the Mongol Empire may have expanded into India were it not for the Delhi Sultanate's role in repelling them.[235] By repeatedly repulsing the Mongol raiders,[236] the sultanate saved India from the devastation waged on West and Central Asia. Soldiers from that region and learned men and administrators fleeing Mongol invasions of Iran migrated into the subcontinent, thereby creating a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north.[235]

A Turco-Mongol conqueror from Central Asia, Timur (Tamerlane), attacked the reigning sultan Nasir-u Din Mehmud of the Tughlaq dynasty in Delhi.[237] The sultan's army was defeated on 17 December 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins after Timur's army had killed and plundered for three days and nights. He ordered the whole city to be sacked except for the sayyids, scholars, and the "other Muslims" (artists); 100,000 war prisoners were said to have been put to death in one day.[238] The sultanate suffered significantly from the sacking of Delhi. Though revived briefly under the Sayyid and Lodi dynasties, it was but a shadow of the former. Lodi rule lasted in Delhi until the defeat of the last sultan, Ibrahim Khan Lodi, in 1526 to the forces of Babur.[239]

-

Qutb Minar, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, whose construction was begun by Qutb ud-Din Aibak, the first Sultan of Delhi.

Vijayanagara Empire

[edit]

The Vijayanagara Empire was established in 1336 by Harihara I and his brother Bukka Raya I of Sangama Dynasty,[240] which originated as a political heir of the Hoysala Empire, Kakatiya Empire,[241] and the Pandyan Empire.[242] The empire rose to prominence as a culmination of attempts by the south Indian powers to ward off Islamic invasions by the end of the 13th century. It lasted until 1646, although its power declined after a major military defeat in 1565 by the combined armies of the Deccan sultanates. The empire is named after its capital city of Vijayanagara, whose ruins surround present day Hampi, now a World Heritage Site in Karnataka, India.[243]

In the first two decades after the founding of the empire, Harihara I gained control over most of the area south of the Tungabhadra river and earned the title of Purvapaschima Samudradhishavara ("master of the eastern and western seas"). By 1374 Bukka Raya I, successor to Harihara I, had defeated the chiefdom of Arcot, the Reddys of Kondavidu, and the Sultan of Madurai and had gained control over Goa in the west and the Tungabhadra-Krishna doab in the north.[244][245]

Harihara II, the second son of Bukka Raya I, further consolidated the kingdom beyond the Krishna River and brought the whole of South India under the Vijayanagara umbrella.[246] The next ruler, Deva Raya I, emerged successful against the Gajapatis of Odisha and undertook important works of fortification and irrigation.[247] Italian traveller Niccolo de Conti wrote of him as the most powerful ruler of India.[248] Deva Raya II succeeded to the throne in 1424 and was possibly the most capable of the Sangama Dynasty rulers.[249] He quelled rebelling feudal lords as well as the Zamorin of Calicut and Quilon in the south. He invaded the island of Sri Lanka and became overlord of the kings of Burma at Pegu and Tanasserim.[250][251][252]

The Vijayanagara Emperors were tolerant of all religions and sects, as writings by foreign visitors show.[253] The kings used titles such as Gobrahamana Pratipalanacharya (literally, "protector of cows and Brahmins") and Hindurayasuratrana (lit, "upholder of Hindu faith") that testified to their intention of protecting Hinduism and yet were at the same time staunchly Islamicate in their court ceremonials and dress.[254] The empire's founders, Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, were devout Shaivas (worshippers of Shiva), but made grants to the Vaishnava order of Sringeri with Vidyaranya as their patron saint, and designated Varaha (an avatar of Vishnu) as their emblem.[255] Nobles from Central Asia's Timurid kingdoms also came to Vijayanagara.[256] The later Saluva and Tuluva kings were Vaishnava by faith, but worshipped at the feet of Lord Virupaksha (Shiva) at Hampi as well as Lord Venkateshwara (Vishnu) at Tirupati.[257] A Sanskrit work, Jambavati Kalyanam by King Krishnadevaraya, called Lord Virupaksha Karnata Rajya Raksha Mani ("protective jewel of Karnata Empire").[258] The kings patronised the saints of the dvaita order (philosophy of dualism) of Madhvacharya at Udupi.[259]

-

Photograph of the ruins of the Vijayanagara Empire at Hampi, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1868[260]

-

Gajashaala, or elephant's stable, was built by the Vijayanagar rulers for their war elephants.[261]

-

Vijayanagara marketplace at Hampi, along with the sacred tank located on the side of Krishna temple.

-

Stone temple car in Vitthala Temple at Hampi

The empire's legacy includes many monuments spread over South India, the best known of which is the group at Hampi. The previous temple building traditions in South India came together in the Vijayanagara Architecture style. The mingling of all faiths and vernaculars inspired architectural innovation of Hindu temple construction. South Indian mathematics flourished under the protection of the Vijayanagara Empire in Kerala. The south Indian mathematician Madhava of Sangamagrama founded the famous Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics in the 14th century which produced a lot of great south Indian mathematicians like Parameshvara, Nilakantha Somayaji and Jyeṣṭhadeva.[262] Efficient administration and vigorous overseas trade brought new technologies such as water management systems for irrigation.[263] The empire's patronage enabled fine arts and literature to reach new heights in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, and Sanskrit, while Carnatic music evolved into its current form.[264]

Vijayanagara went into decline after the defeat in the Battle of Talikota (1565). After the death of Aliya Rama Raya in the Battle of Talikota, Tirumala Deva Raya started the Aravidu dynasty, moved and founded a new capital of Penukonda to replace the destroyed Hampi, and attempted to reconstitute the remains of Vijayanagara Empire.[265] Tirumala abdicated in 1572, dividing the remains of his kingdom to his three sons, and pursued a religious life until his death in 1578. The Aravidu dynasty successors ruled the region but the empire collapsed in 1614, and the final remains ended in 1646, from continued wars with the Bijapur sultanate and others.[266][267][268] During this period, more kingdoms in South India became independent and separate from Vijayanagara. These include the Mysore Kingdom, Keladi Nayaka, Nayaks of Madurai, Nayaks of Tanjore, Nayakas of Chitradurga and Nayak Kingdom of Gingee – all of which declared independence and went on to have a significant impact on the history of South India in the coming centuries.[266]

Other kingdoms

[edit]-

Vijaya Stambha (Tower of Victory).

-

Temple inside Chittorgarh fort

-

Man Singh (Manasimha) palace at the Gwalior fort

-

Chinese manuscript Tribute Giraffe with Attendant, depicting a giraffe presented by Bengali envoys in the name of Sultan Saifuddin Hamza Shah of Bengal to the Yongle Emperor of Ming China

-

Mahmud Gawan Madrasa was built by Mahmud Gawan, the Wazir of the Bahmani Sultanate as the centre of religious as well as secular education

For two and a half centuries from the mid-13th century, politics in Northern India was dominated by the Delhi Sultanate, and in Southern India by the Vijayanagar Empire. However, there were other regional powers present as well. After fall of Pala Empire, the Chero dynasty ruled much of Eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand from the 12th to the 18th centuries.[269][270][271] The Reddy dynasty successfully defeated the Delhi Sultanate and extended their rule from Cuttack in the north to Kanchi in the south, eventually being absorbed into the expanding Vijayanagara Empire.[272]

In the north, the Rajput kingdoms remained the dominant force in Western and Central India. The Mewar dynasty under Maharana Hammir defeated and captured Muhammad Tughlaq with the Bargujars as his main allies. Tughlaq had to pay a huge ransom and relinquish all of Mewar's lands. After this event, the Delhi Sultanate did not attack Chittor for a few hundred years. The Rajputs re-established their independence, and Rajput states were established as far east as Bengal and north into the Punjab. The Tomaras established themselves at Gwalior, and Man Singh Tomar reconstructed the Gwalior Fort.[273] During this period, Mewar emerged as the leading Rajput state; and Rana Kumbha expanded his kingdom at the expense of the Sultanates of Malwa and Gujarat.[273][274] The next great Rajput ruler, Rana Sanga of Mewar, became the principal player in Northern India. His objectives grew in scope – he planned to conquer Delhi. But, his defeat in the Battle of Khanwa consolidated the new Mughal dynasty in India.[273] The Mewar dynasty under Maharana Udai Singh II faced further defeat by Mughal emperor Akbar, with their capital Chittor being captured. Due to this event, Udai Singh II founded Udaipur, which became the new capital of the Mewar kingdom. His son, Maharana Pratap of Mewar, firmly resisted the Mughals. Akbar sent many missions against him. He survived to ultimately gain control of all of Mewar, excluding the Chittor Fort.[275]

In the south, the Bahmani Sultanate in the Deccan, born from a rebellion in 1347 against the Tughlaq dynasty,[276] was the chief rival of Vijayanagara, and frequently created difficulties for them.[277] Starting in 1490, the Bahmani Sultanate's governors revolted, their independent states composing the five Deccan sultanates; Ahmadnagar declared independence, followed by Bijapur and Berar in the same year; Golkonda became independent in 1518 and Bidar in 1528.[278] Although generally rivals, they allied against the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565, permanently weakening Vijayanagar in the Battle of Talikota.[279][280]

In the East, the Gajapati Kingdom remained a strong regional power to reckon with, associated with a high point in the growth of regional culture and architecture. Under Kapilendradeva, Gajapatis became an empire stretching from the lower Ganga in the north to the Kaveri in the south.[281] In Northeast India, the Ahom Kingdom was a major power for six centuries;[282][283] led by Lachit Borphukan, the Ahoms decisively defeated the Mughal army at the Battle of Saraighat during the Ahom-Mughal conflicts.[284] Further east in Northeastern India was the Kingdom of Manipur, which ruled from their seat of power at Kangla Fort and developed a sophisticated Hindu Gaudiya Vaishnavite culture.[285][286][287]

The Sultanate of Bengal was the dominant power of the Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta, with a network of mint towns spread across the region. It was a Sunni Muslim monarchy with Indo-Turkic, Arab, Abyssinian and Bengali Muslim elites. The sultanate was known for its religious pluralism where non-Muslim communities co-existed peacefully. The Bengal Sultanate had a circle of vassal states, including Odisha in the southwest, Arakan in the southeast, and Tripura in the east. In the early 16th century, the Bengal Sultanate reached the peak of its territorial growth with control over Kamrup and Kamata in the northeast and Jaunpur and Bihar in the west. It was reputed as a thriving trading nation and one of Asia's strongest states. The Bengal Sultanate was described by contemporary European and Chinese visitors as a relatively prosperous kingdom and the "richest country to trade with". The Bengal Sultanate left a strong architectural legacy. Buildings from the period show foreign influences merged into a distinct Bengali style. The Bengal Sultanate was also the largest and most prestigious authority among the independent medieval Muslim-ruled states in the history of Bengal. Its decline began with an interregnum by the Suri Empire, followed by Mughal conquest and disintegration into petty kingdoms.

Bhakti movement and Sikhism

[edit]The Bhakti movement refers to the theistic devotional trend that emerged in medieval Hinduism[288] and later revolutionised in Sikhism.[289] It originated in the seventh-century south India (now parts of Tamil Nadu and Kerala), and spread northwards.[288] It swept over east and north India from the 15th century onwards, reaching its zenith between the 15th and 17th century.[290]

- The Bhakti movement regionally developed around different gods and goddesses, such as Vaishnavism (Vishnu), Shaivism (Shiva), Shaktism (Shakti goddesses), and Smartism.[291][292][293] The movement was inspired by many poet-saints, who championed a wide range of philosophical positions ranging from theistic dualism of Dvaita to absolute monism of Advaita Vedanta.[294][295]

- Sikhism is a monotheistic and panentheistic religion based on the spiritual teachings of Guru Nanak, the first Guru,[296] and the ten successive Sikh gurus. After the death of the tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, became the literal embodiment of the eternal, impersonal Guru, where the scripture's word serves as the spiritual guide for Sikhs.[297][298][299]

- Buddhism in India flourished in the Himalayan kingdoms of Namgyal Kingdom in Ladakh, Sikkim Kingdom in Sikkim, and Chutia Kingdom in Arunachal Pradesh of the Late medieval period.

-

Rang Ghar, built by Pramatta Singha in Ahom kingdom's capital Rangpur, is one of the earliest pavilions of outdoor stadia in the Indian subcontinent

-

Chittor Fort is the largest fort on the Indian subcontinent; it is one of the six Hill Forts of Rajasthan

-

Ranakpur Jain temple was built in the 15th century with the support of the Rajput state of Mewar

-

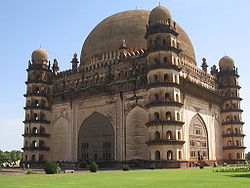

Gol Gumbaz built by the Bijapur Sultanate, has the second largest pre-modern dome in the world after the Byzantine Hagia Sophia

Early modern period (1526–1858)

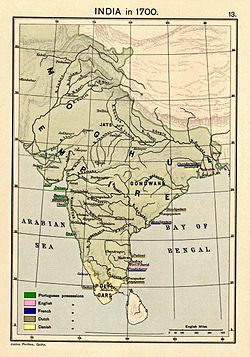

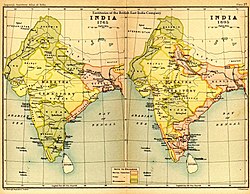

[edit]The early modern period of Indian history is dated from 1526 to 1858, corresponding to the rise and fall of the Mughal Empire, which inherited from the Timurid Renaissance. During this age India's economy expanded, relative peace was maintained and arts were patronised. This period witnessed the further development of Indo-Islamic architecture;[300][301] the growth of Marathas and Sikhs enabled them to rule significant regions of India in the waning days of the Mughal empire.[16] With the discovery of the Cape route in the 1500s, the first Europeans to arrive by sea and establish themselves, were the Portuguese in Goa and Bombay.[302]

Mughal Empire

[edit]In 1526, Babur swept across the Khyber Pass and established the Mughal Empire, which at its zenith covered much of South Asia.[304] However, his son Humayun was defeated by the Afghan warrior Sher Shah Suri in 1540, and Humayun was forced to retreat to Kabul. After Sher Shah's death, his son Islam Shah Suri and his Hindu general Hemu Vikramaditya established secular rule in North India from Delhi until 1556, when Akbar (r. 1556–1605), grandson of Babur, defeated Hemu in the Second Battle of Panipat on 6 November 1556 after winning Battle of Delhi. Akbar tried to establish a good relationship with the Hindus. Akbar declared "Amari" or non-killing of animals in the holy days of Jainism. He rolled back the jizya tax for non-Muslims. The Mughal emperors married local royalty, allied themselves with local maharajas, and attempted to fuse their Turko-Persian culture with ancient Indian styles, creating a unique Indo-Persian culture and Indo-Saracenic architecture.

Akbar married a Rajput princess, Mariam-uz-Zamani, and they had a son, Jahangir (r. 1605–1627).[305] Jahangir followed his father's policy. The Mughal dynasty ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600. The reign of Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658) was the golden age of Mughal architecture. He erected several large monuments, the most famous of which is the Taj Mahal at Agra.

It was one of the largest empires to have existed in the Indian subcontinent,[306] and surpassed China to become the world's largest economic power, controlling 24.4% of the world economy,[307] and the world leader in manufacturing,[308] producing 25% of global industrial output.[309] The economic and demographic upsurge was stimulated by Mughal agrarian reforms that intensified agricultural production,[310] and a relatively high degree of urbanisation.[311]

-

Fatehpur Sikri, near Agra, showing Buland Darwaza, the complex built by Akbar, the third Mughal emperor

-

Red Fort, Delhi, constructed in the year 1648

The Mughal Empire reached the zenith of its territorial expanse during the reign of Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), under whose reign India surpassed Qing China as the world's largest economy.[312][313] Aurangzeb was less tolerant than his predecessors, reintroducing the jizya tax and destroying several historical temples, while at the same time building more Hindu temples than he destroyed,[314] employing significantly more Hindus in his imperial bureaucracy than his predecessors, and advancing administrators based on ability rather than religion.[315] However, he is often blamed for the erosion of the tolerant syncretic tradition of his predecessors, as well as increasing religious controversy and centralisation. The English East India Company suffered a defeat in the Anglo-Mughal War.[316][317]

The Mughals suffered several blows due to invasions from Marathas, Rajputs, Jats and Afghans. In 1737, the Maratha general Bajirao of the Maratha Empire invaded and plundered Delhi. Under the general Amir Khan Umrao Al Udat, the Mughal Emperor sent 8,000 troops to drive away the 5,000 Maratha cavalry soldiers. Baji Rao easily routed the novice Mughal general. In 1737, in the final defeat of Mughal Empire, the commander-in-chief of the Mughal Army, Nizam-ul-mulk, was routed at Bhopal by the Maratha army. This essentially brought an end to the Mughal Empire.[citation needed] While Bharatpur State under Jat ruler Suraj Mal, overran the Mughal garrison at Agra and plundered the city.[318] In 1739, Nader Shah, emperor of Iran, defeated the Mughal army at the Battle of Karnal.[319] After this victory, Nader captured and sacked Delhi, carrying away treasures including the Peacock Throne.[320] Ahmad Shah Durrani commenced his own invasions as ruler of the Durrani Empire, eventually sacking Delhi in 1757.[321] Mughal rule was further weakened by constant native Indian resistance; Banda Singh Bahadur led the Sikh Khalsa against Mughal religious oppression; Hindu Rajas of Bengal, Pratapaditya and Raja Sitaram Ray revolted; and Maharaja Chhatrasal, of Bundela Rajputs, fought the Mughals and established the Panna State.[322] The Mughal dynasty was reduced to puppet rulers by 1757. Vadda Ghalughara took place under the Muslim provincial government based at Lahore to wipe out the Sikhs, with 30,000 Sikhs being killed, an offensive that had begun with the Mughals, with the Chhota Ghallughara,[323] and lasted several decades under its Muslim successor states.[324]

Maratha Empire

[edit]The Maratha kingdom was founded and consolidated by Chatrapati Shivaji.[325] However, the credit for making the Marathas formidable power nationally goes to Peshwa (chief minister) Bajirao I. Historian K.K. Datta wrote that Bajirao I "may very well be regarded as the second founder of the Maratha Empire".[326]

In the early 18th century, under the Peshwas, the Marathas consolidated and ruled over much of South Asia. The Marathas are credited to a large extent for ending Mughal rule in India.[327][328][329] In 1737, the Marathas defeated a Mughal army in their capital, in the Battle of Delhi. The Marathas continued their military campaigns against the Mughals, Nizam, Nawab of Bengal and the Durrani Empire to further extend their boundaries. At its peak, the domain of the Marathas encompassed most of the Indian subcontinent.[330] The Marathas even attempted to capture Delhi and discussed putting Vishwasrao Peshwa on the throne there in place of the Mughal emperor.[331]

The Maratha empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu in the south,[332] to Peshawar (modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan[333] [note 2]) in the north, and Bengal in the east. The Northwestern expansion of the Marathas was stopped after the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). However, the Maratha authority in the north was re-established within a decade under Peshwa Madhavrao I.[335]