Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shia Islam

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

Shia Islam[a] is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib (r. 656–661) as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood to have been usurped by a number of Muhammad's companions at the meeting of Saqifa, during which they appointed Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) as caliph instead. As such, Sunni Muslims believe Abu Bakr, Umar (r. 634–644), Uthman (r. 644–656) and Ali to be 'rightly-guided caliphs', whereas Shia Muslims regard only Ali as the legitimate successor.

Shia Muslims believe that the imamate continued through Ali's sons, Hasan and Husayn, after which various Shia branches developed and recognized different imams. They revere the ahl al-bayt, the family of Muhammad, maintaining that they possess divine knowledge. Shia holy sites include the shrine of Ali in Najaf, the shrine of Husayn in Karbala, and other mausoleums of the ahl al-bayt. Later events, such as Husayn's martyrdom in the Battle of Karbala (680 CE), further influenced the development of Shia Islam, contributing to the formation of a distinct religious sect with its own rituals and shared collective memory.[1]

Shia Islam is followed by 10–15%[2] of all Muslims, numbering at an estimated 200–300 million followers worldwide as of 2025. The three main Shia branches are Twelverism, Isma'ilism, and Zaydism. Shia Muslims form a majority of the population in Iran, Iraq, and Azerbaijan, as well as about half of the citizen population of Bahrain.[3] Significant Shia communities are also found in Lebanon, Kuwait, Turkey, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan and the Indian subcontinent. Iran stands as the world's only country where Shia Islam forms the foundation of both its laws and governance system.[4]

Terminology

[edit]The word Shia (or Shīʿa) (/ˈʃiːə/) (Arabic: شيعيّ, romanized: shīʿī, pl. shīʿiyyūn) is derived from شيعة علي, shīʿat ʿAlī, 'followers of Ali'.[5][6][7] Shia Islam is also referred to in English as Shiism (or Shīʿism) (/ˈʃiːɪz(ə)m/), and Shia Muslims as Shiites (or Shīʿites) (/ˈʃiːaɪt/).[8]

The term Shia was first used during Muhammad's lifetime.[9] At present, the word refers to the Muslims who believe that the leadership of the Muslim community after Muhammad belongs to ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law, and his successors.[10] Nawbakhti states that the term Shia refers to a group of Muslims who at the time of Muhammad and after him regarded ʿAlī as the Imam and caliph.[10][11] Al-Shahrastani expresses that the term Shia refers to those who believe that ʿAlī is designated as the heir, Imam, and caliph by Muhammad[10][12] and that ʿAlī's authority is maintained through his descendants.[10][13] For the adherents of Shia Islam, this conviction is implicit in the Quran and the history of Islam. Shia Muslim scholars emphasize that the notion of authority is linked to the family of the Abrahamic prophets as the Quranic verses 3:33 and 3:34 show: "Indeed, Allah chose Adam, Noah, the family of Abraham, and the family of ’Imrân above all people. They are descendants of one another. And Allah is All-Hearing, All-Knowing."[14]

History

[edit]The original Shia identity referred to the followers of Imam ʿAlī,[15] and Shia theology was formulated after the hijra (8th century CE).[16] The first Shia governments and societies were established by the end of the 9th century CE. The 10th century CE has been referred to by the scholar of Islamic studies Louis Massignon as "the Shiite Ismaili century in the history of Islam".[17]

Origins

[edit]

The Shia, originally known as the "partisans" of ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, Muhammad's cousin and Fatima's husband, first emerged as a distinct movement during the First Fitna from 656 to 661 CE. Shia doctrine holds that ʿAlī was meant to lead the community after Muhammad's death in 632. Historians dispute over the origins of Shia Islam, with many Western scholars positing that Shia Islam began as a political faction rather than a truly religious movement.[18][19] Other scholars disagree, considering this concept of religious-political separation to be an anachronistic application of a Western concept.[20]

Shia Muslims believe that Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his heir during a speech at Ghadir Khumm.[21] The point of contention between different Muslim sects arises when Muhammad, whilst giving his speech, gave the proclamation "Anyone who has me as his mawla, has ʿAlī as his mawla".[10][22][23][24] Some versions add the additional sentence "O God, befriend the friend of ʿAlī and be the enemy of his enemy".[25] Sunnis maintain that Muhammad emphasized the deserving friendship and respect for ʿAlī. In contrast, Shia Muslims assert that the statement unequivocally designates ʿAlī as Muhammad's appointed successor.[10][26][27][28] Shia sources also record further details of the event, such as stating that those present congratulated ʿAlī and acclaimed him as Amir al-Mu'minin ("commander of the believers").[25]

When Muhammad died in 632 CE, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib and Muhammad's closest relatives made the funeral arrangements. While they were preparing his body, Abū Bakr, ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, and Abu Ubaidah ibn al Jarrah met with the leaders of Medina and elected Abū Bakr as the first rāshidūn caliph. Abū Bakr served from 632 to 634, and was followed by Umar (634–644) and ʿUthmān (644–656).[21]

With the murder of ʿUthmān in 657 CE, the Muslims of Medina invited ʿAlī to become the fourth caliph as the last source,[29] and he established his capital in Kufa.[5] ʿAlī's rule over the early Islamic empire, between 656 CE to 661 CE, was often contested.[21] Tensions eventually led to the First Fitna, the first major civil war between Muslims within the empire, which began as a series of revolts fought against ʿAlī. While the rebels had previously affirmed the legitimacy of ʿAlī's khilafāʾ (caliphate), they later turned against ʿAlī and fought him.[29]

Tensions escalated into the Battle of the Camel in 656, where Ali's forces emerged victorious against Aisha, Talhah, and al-Zubayr. The Battle of Siffin in 657 turned the tide against ʿAlī, who lost due to arbitration issues with Muawiyah, the governor of Damascus.[21] ʿAlī withdrew to Kufa, overcoming the Kharijis, a faction that had transformed from supporters to bitter rivals, at Nahrawan in 658. In 661, ʿAlī was assassinated by a Khariji assassin in Kufa while in the act of prostration during prayer (sujud). Subsequently, Muawiyah asserted his claim to the caliphate.[31][30]

Hasan, Husayn, and Karbala

[edit]

Upon the death of ʿAlī, his elder son Ḥasan became leader of the Muslims of Kufa. After a series of skirmishes between the Kufa Muslims and the army of Muawiyah, Ḥasan ibn Ali agreed to cede the caliphate to Muawiyah and maintain peace among Muslims upon certain conditions: The enforced public cursing of ʿAlī, e.g. during prayers, should be abandoned; Muawiyah should not use tax money for his own private needs; There should be peace, and followers of Ḥasan should be given security and their rights; Muawiyah will never adopt the title of Amir al-Mu'minin ("commander of the believers"); Muawiyah will not nominate any successor.[32][33] Ḥasan then retired to Medina, where in 670 CE he was poisoned by his wife Ja'da bint al-Ash'ath, after being secretly contacted by Muawiyah who wished to pass the caliphate to his own son Yazid and saw Ḥasan as an obstacle.[34]

Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, ʿAlī's younger son and brother to Ḥasan, initially resisted calls to lead the Muslims against Muawiyah and reclaim the caliphate. In 680 CE, Muawiyah died and passed the caliphate to his son Yazid, thus breaking the treaty with Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī. Yazid asked Husayn to swear allegiance (bay'ah) to him. ʿAlī's faction, having expected the caliphate to return to ʿAlī's line upon Muawiyah's death, saw this as a betrayal of the peace treaty and so Ḥusayn rejected this request for allegiance. There was a groundswell of support in Kufa for Ḥusayn to return there and take his position as caliph and Imam, so Ḥusayn collected his family and followers in Medina and set off for Kufa.[21]

En route to Kufa, Husayn was blocked by an army of Yazid's men, which included people from Kufa, near Karbala. Rather than surrendering, Husayn and his followers chose to fight. In the Battle of Karbala, Ḥusayn and approximately 72 of his family members and followers were killed, and Husayn's head was delivered to Yazid in Damascus. The Shi'a community regard Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī as a martyr (shahid), and count him as an Imam from the Ahl al-Bayt. The Battle of Karbala and martyrdom of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī is often cited as the definitive separation between the Shia and Sunnī sects of Islam. Ḥusayn is the last Imam following ʿAlī mutually recognized by all branches of Shia Islam.[35] The martyrdom of Husayn and his followers is commemorated on the Day of Ashura, occurring on the tenth day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar.[21]

Imamate of the Ahl al-Bayt

[edit]

Later, most denominations of Shia Islam, including Twelvers and Ismāʿīlīs, became Imamis.[10][37][38] Shia Muslims believe that Imams are the spiritual and political successors to Muhammad.[39] Imams are human individuals who not only rule over the Muslim community with justice, but also are able to keep and interpret the divine law and its esoteric meaning. The words and deeds of Muhammad and the Imams are a guide and model for the community to follow; as a result, they must be free from error and sin, and must be chosen by divine decree (nass) through Muhammad.[40][41] According to this view peculiar to Shia Islam, there is always an Imam of the Age, who is the divinely appointed authority on all matters of faith and law in the Muslim community. ʿAlī was the first Imam of this line, the rightful successor to Muhammad, followed by male descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah.[39][42]

This difference between following either the Ahl al-Bayt (Muhammad's family and descendants) or pledging allegiance to Abū Bakr has shaped the Shia–Sunnī divide on the interpretation of some Quranic verses, hadith literature (accounts of the sayings and living habits attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad during his lifetime), and other areas of Islamic belief throughout the history of Islam. For instance, the hadith collections venerated by Shia Muslims are centered on narrations by members of the Ahl al-Bayt and their supporters, while some hadith transmitted by narrators not belonging to or supporting the Ahl al-Bayt are not included.

Those of Abu Hurairah, for example, Ibn Asakir in his Taʿrikh Kabir, and Muttaqi in his Kanzuʿl-Umma report that ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb lashed him, rebuked him, and forbade him to narrate ḥadīth from Muhammad. ʿUmar is reported to have said: "Because you narrate hadith in large numbers from the Holy Prophet, you are fit only for attributing lies to him. (That is, one expects a wicked man like you to utter only lies about the Holy Prophet.) So you must stop narrating hadith from the Prophet; otherwise, I will send you to the land of Dus." (An Arab clan in Yemen, to which Abu Hurairah belonged).

According to Sunnī Muslims, ʿAlī was the fourth successor to Abū Bakr, while Shia Muslims maintain that ʿAlī was the first divinely sanctioned "Imam", or successor of Muhammad. The seminal event in Shia history is the martyrdom at the Battle of Karbala of ʿAlī's son, Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, and 71 of his followers in 680 CE, who led a non-allegiance movement against the defiant caliph.

It is believed in Twelver and Ismāʿīlī branches of Shia Islam that divine wisdom (ʿaql) was the source of the souls of the prophets and Imams, which bestowed upon them esoteric knowledge (ḥikmah), and that their sufferings were a means of divine grace to their devotees.[43][44] Although the Imam was not the recipient of a divine revelation (waḥy), he had a close relationship with God, through which God guides him, and the Imam, in turn, guides the people. Imamate, or belief in the divine guide, is a fundamental belief in the Twelver and Ismāʿīlī branches of Shia Islam, and is based on the concept that God would not leave humanity without access to divine guidance.[45]

Imam Mahdi, last Imam of the Shia

[edit]

In Shia Islam, Imam Mahdi is regarded as the prophesied eschatological redeemer of Islam who will rule for seven, nine, or nineteen years (according to differing interpretations) before the Day of Judgment and will rid the world of evil. According to Islamic tradition, the Mahdi's tenure will coincide with the Second Coming of Jesus (ʿĪsā), who is to assist the Mahdi against the Masih ad-Dajjal (literally, the "false Messiah" or Antichrist). Jesus, who is considered the Masih ("Messiah") in Islam, will descend at the point of a white arcade east of Damascus, dressed in yellow robes with his head anointed. He will then join the Mahdi in his war against the Dajjal, where it is believed the Mahdi will slay the Dajjal and unite humankind.

Dynasties

[edit]In the century following the Battle of Karbala (680 CE), as various Shia-affiliated groups diffused in the emerging Islamic world, several nations arose based on a Shia leadership or population.

- Idrisids (788–985 CE): a Zaydi dynasty in what is now Morocco.

- Qarmatians (899–1077 CE): an Ismaili Iranian dynasty. Their headquarters were in Eastern Arabia and Bahrain. It was founded by Abu Sa'id al-Jannabi.

- Buyids (934–1055 CE): a Twelver Iranian dynasty. at its peak consisted of large portions of Iran and Iraq.

- Uqaylids (990–1096 CE): a Shia Arab dynasty with several lines that ruled in various parts of al-Jazira, northern Syria and Iraq.

- Ilkhanate (1256–1335): a Persianate Mongol khanate established in Iran in the 13th century, considered a part of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanate was based, originally, on Genghis Khan's campaigns in the Khwarezmid Empire in 1219–1224, and founded by Genghis's grandson, Hulagu, in territories in Western and Central Asia which today comprise most of Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and Pakistan. The Ilkhanate initially embraced many religions, but was particularly sympathetic to Buddhism and Christianity. Later Ilkhanate rulers, beginning with Ghazan in 1295, chose Islam as the state religion; his brother Öljaitü promoted Shia Islam.[46]

- Bahmanids (1347–1527): a Shia Muslim state of the Deccan Plateau in Southern India, and one of the great medieval Indian kingdoms.[47] Bahmanid Sultanate was the first independent Islamic kingdom in Southern India.[48]

Fatimid Caliphate

[edit]

- Fatimids (909–1171 CE): Controlled much of North Africa, the Levant, parts of Arabia, and the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The group takes its name from Fāṭimah, Muhammad's daughter, from whom they claim descent.

- In 909 CE, the Shia military leader Abu Abdallah al-Shiʻi overthrew the Sunni rulers in North Africa, an event which led to the foundation of the Fatimid Caliphate.[49]

- Al-Qaid Jawhar ibn Abdallah (Arabic: جوهر; fl. 966–d. 992) was a Shia Fatimid general. Under the command of Caliph al-Muʻizz, he led the conquest of North Africa and then of Egypt,[50] founded the city of Cairo[51] and the al-Azhar Mosque. A Greek slave by origin, he was freed by al-Muʻizz.[52]

Safavid Empire

[edit]

A major turning point in the history of Shia Islam was the dominion of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) in Persia. This caused a number of changes in the Muslim world:

- The ending of the relative mutual tolerance between Sunnis and Shias that existed from the time of the Mongol conquests onwards and the resurgence of antagonism between the two groups.

- Initial dependence of Shia clerics on the state followed by the emergence of an independent body of ulama capable of taking a political stand different from official policies.[55]

- The growth in importance of Persian centers of Islamic education and religious learning, which resulted in the change of Twelver Shia Islam from being a predominantly Arab phenomenon to become predominantly Persian.[56]

- The growth of the Akhbari school of thought, which taught that only the Quran, ḥadīth literature, and sunnah (accounts of the sayings and living habits attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad during his lifetime) are to be bases for verdicts, rejecting the use of reasoning.

With the fall of the Safavids, the state in Iran—including the state system of courts with government-appointed judges (qāḍī)—became much weaker. This gave the sharīʿa courts of mujtahid an opportunity to fill the legal vacuum and enabled the ulama to assert their judicial authority. The Usuli school of thought also increased in strength at this time.[57]

-

The declaration of Twelver Shīʿīsm as the state religion of Safavids

-

A monument commemorating the Battle of Chaldiran, where more than 7,000 Muslims of the Shia and Sunnī sects killed each other

Beliefs

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: cluttered, inconsistent, and confusing. (October 2022) |

Shia Islam encompasses various denominations and subgroups,[5] all bound by the belief that the leader of the Muslim community (Ummah) should hail from Ahl al-Bayt, the family of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[21] It embodies a completely independent system of religious interpretation and political authority in the Muslim world.[58][59]

Alī: Muhammad's rightful successor

[edit]

Shia Muslims believe that just as a prophet is appointed by God alone, only God has the prerogative to appoint the successor to his prophet. They believe God chose ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib to be Muhammad's successor and the first caliph (Arabic: خليفة, romanized: khalifa) of Islam. Shia Muslims believe that Muhammad designated Ali as his successor by God's command in several instances, but most notably at Eid Al Ghadir.[60][61] Additionally, ʿAlī was Muhammad's first-cousin, closest living male relative, and his son-in-law, having married Muhammad's daughter, Fāṭimah.[29][30]

Profession of faith (Shahada)

[edit]

The Shia version of the Shahada (Arabic: الشهادة), the Islamic profession of faith, differs from that of the Sunnīs.[62] The Sunnī version of the Shahada states La ilaha illallah, Muhammadun rasulullah (Arabic: لَا إِلٰهَ إِلَّا الله مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ الله, lit. 'There is no god except God, Muhammad is the messenger of God'); Shia Muslims add the phrase Ali-un-Waliullah (Arabic: علي ولي الله, lit. 'Ali is the friend of God'). The basis for the Shia belief in ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as the Wali of God is derived from the Qur'anic verse 5:55.

This additional phrase to the declaration of faith embodies the Shia emphasis on the inheritance of authority through Muhammad's family and lineage. The three clauses of the Shia version of the Shahada thus address the fundamental Islamic beliefs of Tawḥīd (Arabic: تَوْحِيد, lit. 'oneness of God'), Nubuwwah (Arabic: نبوة, lit. 'prophethood'), and Imamah (Arabic: إمامة, lit. 'Imamate or leadership').[63]

Infallibility (Ismah)

[edit]Ismah (Arabic: عِصْمَة, romanized: 'Iṣmah or 'Isma, lit. 'protection') is the concept of infallibility or "divinely bestowed freedom from error and sin" in Islam.[64] Muslims believe that Muhammad, along with the other prophets and messengers, possessed ismah. Twelver and Ismāʿīlī Shia Muslims also attribute the quality to Imams as well as to Fāṭimah, daughter of Muhammad, in contrast to the Zaydī Shias, who do not attribute ismah to the Imams.[65] Though initially beginning as a political movement, infallibility and sinlessness of the Imams later evolved as a distinct belief of (non-Zaydī) Shia Islam.[66]

According to Shia Muslim theologians, infallibility is considered a rational, necessary precondition for spiritual and religious guidance. They argue that since God has commanded absolute obedience from these figures, they must only order that which is right. The state of infallibility is based on the Shia interpretation of the verse of purification.[67][68] Thus, they are the most pure ones, the only immaculate ones preserved from, and immune to, all uncleanness.[69] It does not mean that supernatural powers prevent them from committing a sin, but due to the fact that they have absolute belief in God, they refrain from doing anything that is a sin.[64]

They[who?] also have complete knowledge of God's will. They are in possession of all knowledge brought by the angels (Arabic: ملائِكة, romanized: malāʾikah) to the prophets (Arabic: أنبياء, romanized: anbiyāʼ) and the messengers (Arabic: رُسل, romanized: rusul). Their knowledge encompasses the totality of all times. Thus, they are believed to act without fault in religious matters.[70] Shi'a Muslims regard ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as the successor of Muhammad, not only ruling over the entire Muslim community in justice, but also in interpreting the Islamic faith, practices, and its esoteric meaning. ʿAlī is regarded as a "perfect man" (Arabic: الإنسان الكامل, romanized: al-insan al-kamil) similar to Muhammad, according to the Shia perspective.[71]

Occultation (Ghaybah)

[edit]

The Occultation is an eschatological belief held in various denominations of Shia Islam concerning a messianic figure, the hidden and last Imam known as "the Mahdi", that one day shall return on Earth and fill the world with justice. According to the doctrine of Twelver Shia Islam, the main goal of Imam Mahdi will be to establish an Islamic state and to apply Islamic laws that were revealed to Muhammad. The Quran does not contain verses on the Imamate, which is the basic doctrine of Shia Islam.[72]

Some Shia subsects, such as the Zaydism and Nizari Isma'ilism, do not believe in the idea of Occultation. The groups that believe in it differ as to which lineage of the Imamate is valid and, therefore, which individual has gone into Occultation. They believe many signs will indicate the time of his return.

Twelver Shia Muslims believe that the prophesied Mahdi and 12th Shia Imam, Hujjat Allah al-Mahdi, is already on Earth in Occultation, and will return at the end of time. Ṭayyibi Ismāʿīlīs and Fatimid/Bohra/Dawoodi Bohra believe the same but for their 21st Ṭayyib, At-Tayyib Abi l-Qasim, and also believe that a Da'i al-Mutlaq ("Unrestricted Missionary") maintains contact with him. Sunnī Muslims believe that the future Mahdi has not yet arrived on Earth.[73][better source needed]

Hadith tradition

[edit]Shia Muslims believe that the status of Ali is supported by numerous ḥadīth reports, including the Hadith of the pond of Khumm, Hadith of the two weighty things, Hadith of the pen and paper, Hadith of the invitation of the close families, and Hadith of the Twelve Successors. In particular, the Hadith of the Cloak is often quoted to illustrate Muhammad's feeling towards ʿAlī and his family by both Sunnī and Shia scholars. Shia Muslims prefer to study and read the hadith attributed to the Ahl al-Bayt and close associates, and most have their own separate hadith canon.[74][75]

Holy Relics (Tabarruk)

[edit]Shia Muslims believe that the armaments and sacred items of all of the Abrahamic prophets, including Muhammad, were handed down in succession to the Imams of the Ahl al-Bayt. Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the 6th Shia Imam, in Kitab al-Kafi mentions that "with me are the arms of the Messenger of Allah. It is not disputable."[76]

Further, he claims that with him is the sword of the Messenger of God, his coat of arms, his Lamam (pennon), and his helmet. In addition, he mentions that with him is the flag of the Messenger of God, the victorious. With him is the Staff of Moses, the ring of Solomon, son of David, and the tray on which Moses used to offer his offerings. With him is the name that whenever the Messenger of God would place it between the Muslims and pagans, no arrow from the pagans would reach the Muslims. With him is a similar object that the angels brought.[76]

Al-Ṣādiq also narrated that the passing down of armaments is synonymous with receiving the Imamat (leadership), similar to how the Ark of the Covenant in the house of the Israelites signaled prophethood.[76] Imam Ali al-Ridha narrates that wherever the armaments among us would go, knowledge would also follow and the armaments would never depart from those with knowledge (Imamat).[76]

Other doctrines

[edit]Doctrine about necessity of acquiring knowledge

[edit]According to Muhammad Rida al-Muzaffar, God gives humans the faculty of reason and argument. Also, God orders humans to think carefully about creation, while he refers to all creations as his signs of power and glory. These signs encompass all of the universe. Furthermore, there is an analogy of humans as the little world and the universe as the large world. God does not accept the faith of those who follow him without thinking and only with imitation, but God also blames them for such actions. In other words, humans have to think about the universe with reason and intellect, a faculty bestowed on us by God. Since there is more insistence on the faculty of intellect among Shia Muslims, even evaluating the claims of someone who claims prophecy is based on the intellect.[77][78]

Practices

[edit]

Shia religious practices, such as prayers, differ only slightly from the Sunnīs. While all Muslims pray five times daily, Shia Muslims have the option of combining Dhuhr with Asr and Maghrib with Isha', as there are three distinct times mentioned in the Quran. The Sunnīs tend to combine only under certain circumstances.

Holidays

[edit]Shia Muslims celebrate the following annual holidays:

- Eid ul-Fitr, which marks the end of fasting during the month of Ramadan

- Eid al-Adha, which marks the end of the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca

- Eid al-Ghadeer, which is the anniversary of the Ghadir Khum, the occasion when Muhammad announced Ali's Imamate before a multitude of Muslims.[79] Eid al-Ghadeer is held on the 18th of Dhu al-Hijjah.

- The Mourning of Muharram and the Day of Ashura for Shia Muslims commemorate the martyrdom of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, brother of Ḥasan and grandson of Muhammad, who was killed by the army of Yazid ibn Muawiyah in Karbala (central Iraq). Ashura is a day of deep mourning which occurs on the 10th of Muharram.

- Arba'een commemorates the suffering of the women and children of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī's household. After Ḥusayn was killed, they were marched over the desert, from Karbala (central Iraq) to Shaam (Damascus, Syria). Many children (some of whom were direct descendants of Muhammad) died of thirst and exposure along the route. Arbaein occurs on the 20th of Safar, 40 days after Ashura.

- Mawlid, Muhammad's birth date. Unlike Sunnī Muslims, who celebrate the 12th of Rabi' al-awwal as Muhammad's day of birth or death (because they assert that his birth and death both occur in this week), Shia Muslims celebrate Muhammad's birthday on the 17th of the month, which coincides with the birth date of Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the 6th Shia Imam.[80]

- Fāṭimah's birthday on 20th of Jumada al-Thani. This day is also considered as the "'women and mothers' day"[81]

- ʿAlī's birthday on 13th of Rajab.

- Mid-Sha'ban is the birth date of the 12th and final Twelver imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi. It is celebrated by Shia Muslims on the 15th of Sha'aban.

- Laylat al-Qadr, anniversary of the night of the revelation of the Quran.

- Eid al-Mubahila celebrates a meeting between the Ahl al-Bayt (household of Muhammad) and a Christian deputation from Najran. Al-Mubahila is held on the 24th of Dhu al-Hijjah.

Holy sites

[edit]

After Mecca and Medina, the two holiest cities of Islam, the cities of Najaf, Karbala, Mashhad and Qom are the most revered by Shia Muslims.[83][84] The Sanctuary of Imām ʿAlī in Najaf, the Shrine of Imam Ḥusayn in Karbala, The Sanctuary of Imam Reza in Mashhad and the Shrine of Fāṭimah al-Maʿṣūmah in Qom are very essential for Shia Muslims. Other venerated pilgrimage sites include the Kadhimiya Mosque in Kadhimiya, Al-Askari Mosque in Samarra, the Sahla Mosque, the Great Mosque of Kufa, the Jamkaran Mosque in Qom, and the Tomb of Daniel in Susa.

Most of the Shia sacred places and heritage sites in Saudi Arabia have been destroyed by the Al Saud-Wahhabi armies of the Ikhwan, the most notable being the tombs of the Imams located in the Al-Baqi' cemetery in 1925.[85] In 2006, a bomb destroyed the shrine of Al-Askari Mosque.[86] (See: Anti-Shi'ism).

Purity

[edit]Shia orthodoxy, particularly in Twelver Shi'ism, has considered non-Muslims as agents of impurity (Najāsat). This categorization sometimes extends to kitābῑ, individuals belonging to the People of the Book, with Jews explicitly labeled as impure by certain Shia religious scholars.[87][88][89] Armenians in Iran, who have historically played a crucial role in the Iranian economy, received relatively more lenient treatment.[88]

Shi'ite theologians and mujtahids (jurists), such as Muḥammad Bāqir Majlisῑ, held that Jews' impurity extended to the point where they were advised to stay at home on rainy or snowy days to prevent contaminating their Shia neighbors. Ayatollah Khomeini, Supreme Leader of Iran from 1979 to 1989, asserted that every part of an unbeliever's body, including hair, nails, and bodily secretions, is impure. However, the current leader of Iran, ʿAlī Khameneʾī, stated in a fatwa that Jews and other Peoples of the Book are not inherently impure, and touching the moisture on their hands does not convey impurity.[87][90][89]

Demographics

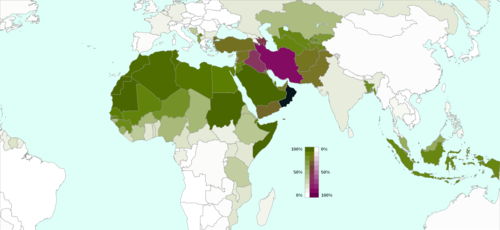

[edit]

Shia Islam is the second largest branch of Islam.[92] It is estimated that 10–13%[93][94][95] of the global Muslim population are Shias. They may number up to 154–200 million as of 2009.[94] In 1985, Shia Muslims were estimated to be 21% of the Muslim population in South Asia, although the total number is difficult to estimate.[96]

Shia Muslims form a distinct majority of the population in three countries of the Muslim world: Iran, Iraq, and Azerbaijan.[97][98] A c. 2008 estimate asserted that Shia Muslims constituted 36.3% of the entire population (and 38.6% of the Muslim population) of the Middle East.[99]

Estimates have placed the proportion of Shia Muslims in Lebanon between 27% and 45% of the population,[97][100] 30–35% of the citizen population in Kuwait (no figures exist for the non-citizen population),[101][102] over 20% in Turkey,[94][103] 5–20% of the population in Pakistan,[104][94] and 10–19% of Afghanistan's population,[105][106] and 45% in Bahrain.[107][108]

Saudi Arabia hosts a number of distinct Shia communities, including the Twelver Baharna in the Eastern Province and Nakhawila of Medina, and the Ismāʿīlī Sulaymani and Zaydī Shias of Najran. Estimations put the number of Shia citizens at roughly 15% of the local population.[109] Approximately 40% of the population of Yemen are Shia Muslims.[110][111]

Significant Shia communities exist in the coastal regions of West Sumatra and Aceh in Indonesia (see Tabuik).[112] The Shia presence is negligible elsewhere in Southeast Asia, where Muslims are predominantly Shāfiʿī Sunnīs.

A significant Shia minority is present in Nigeria, made up of modern-era converts to a Shia movement centered around Kano and Sokoto states.[94][95][113] Several African countries like Kenya,[114] South Africa,[115] Somalia,[116] etc. hold small minority populations of various Shia subsects, primarily descendants of immigrants from South Asia during the colonial period, such as the Khoja.[117]

Significant populations worldwide

[edit]Figures indicated in the first three columns below are based on the October 2009 demographic study by the Pew Research Center report, Mapping the Global Muslim Population.[94][95]

| Country | Article | Shia population in 2009 (Pew)[94][95] | Percent of population that is Shia in 2009 (Pew)[94][95] | Percent of global Shia population in 2009 (Pew)[94][95] | Population estimate ranges and notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam in Iran | 66,000,000–69,500,000 | 90–95 | 37–40 | ||

| Shia Islam in the Indian subcontinent | 25,272,000 | 15 | 15 | A 2023 census estimate was that Shia made up about 15-20% of Pakistan's population.[118] | |

| Shi'a Islam in Iraq | 19,000,000–24,000,000 | 55–65 | 10–11 | ||

| Shia Islam in the Indian subcontinent | 12,300,000–18,500,000 | 1.3–2 | 9–14 | ||

| Shia Islam in Yemen | 7,000,000–8,000,000 | 35–40 | ~5 | Majority following Zaydi Shia sect. | |

| Shi'a Islam in Turkey | 6,000,000–9,000,000 | ~10–15 | ~3–4 | Majority following Alevi Shia sect. | |

| Islam in Azerbaijan | 4,575,000–5,590,000 | 45–55 | 2–3 | Azerbaijan is majority Shia.[119][120][121] A 2012 work noted that in Azerbaijan, among believers of all faiths, 10% identified as Sunni, 30% identified as Shia, and the remainder of followers of Islam simply identified as Muslim.[121] | |

| Shi'a Islam in Afghanistan | 3,000,000 | 15 | ~2 | A reliable census has not been taken in Afghanistan in decades, but about 20% of Afghan population is Shia, mostly among ethnic Tajik and Hazara minorities.[122] | |

| Islam in Syria | 2,400,000 | 13 | ~2 | Majority following Alawites Shia sect. | |

| Shi'a Islam in Lebanon | 2,100,000 | 31.2 | <1 | In 2020, the CIA World Factbook stated that Shia Muslims constitute 31.2% of Lebanon's population.[123] | |

| Shi'a Islam in Saudi Arabia | 2,000,000 | ~6 | |||

| Shi'a Islam in Nigeria | <2,000,000 | <1 | <1 | Estimates range from as low as 2% of Nigeria's Muslim population to as high as 17% of Nigeria's Muslim population.[b] Some, but not all, Nigerian Shia are affiliated with the banned Islamic Movement in Nigeria, an Iranian-inspired Shia organization led by Ibrahim Zakzaky.[124] | |

| Islam in Tanzania | ~1,500,000 | ~2.5 | <1 | ||

| Shi'a Islam in Kuwait | 500,000–700,000 | 20–25 | <1 | Among Kuwait's estimated 1.4 million citizens, about 30% are Shia (including Ismaili and Ahmadi, whom the Kuwaiti government count as Shia). Among Kuwait's large expatriate community of 3.3 million noncitizens, about 64% are Muslim, and among expatriate Muslims, about 5% are Shia.[126] | |

| Islam in Bahrain | 400,000–500,000 | 65–70 | <1 | ||

| Shi'a Islam in Tajikistan | ~400,000 | ~4 | <1 | Shi'a Muslims in Tajikistan are predominantly Nizari Ismaili | |

| Islam in Germany | ~400,000 | ~0.5 | <1 | ||

| Islam in the United Arab Emirates | ~300,000 | ~3 | <1 | ||

| Islam in the United States Shia Islam in the Americas |

~225,000 | ~0.07 | <1 | Shi'a form a majority amongst Arab Muslims in many American cities, e.g. Lebanese Shi'a forming the majority in Detroit.[127] | |

| Islam in the United Kingdom | ~125,000 | ~0.2 | <1 | ||

| Islam in Qatar | ~100,000 | ~3.5 | <1 | ||

| Islam in Oman | ~100,000 | ~2 | <1 | As of 2015, about 5% of Omanis are Shia (compared to about 50% Ibadi and 45% Sunni).[128] |

Major denominations or branches

[edit]The Shia community throughout its history split over the issue of the Imamate. The largest branch are the Twelvers, followed by the Zaydīs and the Ismāʿīlīs. Each subsect of Shia Islam follows its own line of Imamate. All mainstream Twelver and Ismāʿīlī Shia Muslims follow the same school of thought, the Jaʽfari jurisprudence, named after Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the 6th Shia Imam. Shia clergymen and jurists usually carry the title of mujtahid (i.e., someone authorized to issue legal opinions in Shia Islam).

Twelver

[edit]Twelver Shia Islam is the largest branch of Shia Islam,[129][92][130][131][132][133] and the terms Shia Muslim and Shia often refer to the Twelvers by default. The designation Twelver is derived from the doctrine of believing in twelve divinely ordained leaders, known as "the Twelve Imams". Twelver Shia are otherwise known as Imami or Jaʿfari; the latter term derives from Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the 6th Shia Imam, who elaborated the Twelver jurisprudence.[134] Twelver Shia constitute the majority of the population in Iran (90%),[135] Iraq (65%) and Azerbaijan (55%).[5][136] Significant populations also exist in Afghanistan, Bahrain (40% of Muslims) and Lebanon (27–29% of Muslims).[137][138]

Doctrine

[edit]Twelver doctrine is based on five principles.[61] These five principles known as Usul ad-Din are as follow:[139]

- Monotheism: God is one and unique;

- Justice: the concept of moral rightness based on ethics, fairness, and equity, along with the punishment of the breach of these ethics;

- Prophethood: the institution by which God sends emissaries, or prophets, to guide humankind;

- Leadership: a divine institution which succeeded the institution of Prophethood. Its appointees (Imams) are divinely appointed;

- Resurrection and Last Judgment: God's final assessment of humanity.

Books

[edit]Besides the Quran, which is the sacred text common to all Muslims, Twelver Shias derive scriptural and authoritative guidance from collections of sayings and traditions (hadith) attributed to Muhammad and the Twelve Imams. Below is a list of some of the most prominent of these books:

- Nahj al-Balagha by Ash-Sharif Ar-Radhi[140] – the most famous collection of sermons, letters & narration attributed to Ali, the first Imam regarded by Shias

- Kitab al-Kafi by Muhammad ibn Ya'qub al-Kulayni[141]

- Wasa'il al-Shiʻah by al-Hurr al-Amili

The Twelve Imams

[edit]According to the theology of Twelvers, the successor of Muhammad is an infallible human individual who not only rules over the Muslim community with justice but also is able to keep and interpret the divine law (sharīʿa) and its esoteric meaning. The words and deeds of Muhammad and the Twelve Imams are a guide and model for the Muslim community to follow; as a result, they must be free from error and sin, and Imams must be chosen by divine decree (nass) through Muhammad.[40][41] The twelfth and final Imam is Hujjat Allah al-Mahdi, who is believed by Twelvers to be currently alive and hidden in Occultation.[45]

Jurisprudence

[edit]The Twelver jurisprudence is called Jaʽfari jurisprudence. In this school of Islamic jurisprudence, the sunnah is considered to be comprehensive of the oral traditions of Muhammad and their implementation and interpretation by the Twelve Imams. There are three schools of Jaʿfari jurisprudence: Usuli, Akhbari, and Shaykhi; the Usuli school is by far the largest of the three. Twelver groups that do not follow the Jaʿfari jurisprudence include Alevis, Bektashi, and Qizilbash.

The five pillars of Islam to the Jaʿfari jurisprudence are known as Usul ad-Din:

- Tawḥīd: unity and oneness of God;

- Nubuwwah: prophethood of Muhammad;

- Muʿad: resurrection and final judgment;

- ʿAdl: justice of God;

- Imamah: the rightful place of the Shia Imams.

In Jaʿfari jurisprudence, there are eight secondary pillars, known as Furu ad-Din, which are as follows:[139]

- Salat (prayer);

- Sawm (fasting);

- Hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca;

- Zakāt (alms giving to the poor);

- Jihād (struggle) for the righteous cause;

- Directing others towards good;

- Directing others away from evil;

- Khums (20% tax on savings yearly, after deduction of commercial expenses).

According to Twelvers, defining and interpretation of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) is the responsibility of Muhammad and the Twelve Imams. Since the 12th Imam is currently in Occultation, it is the duty of Shia clerics to refer to the Islamic literature, such as the Quran and hadith, and identify legal decisions within the confines of Islamic law to provide means to deal with current issues from an Islamic perspective. In other words, clergymen in Twelver Shia Islam are believed to be the guardians of fiqh, which is believed to have been defined by Muhammad and his twelve successors. This process is known as ijtihad and the clerics are known as marjaʿ, meaning "reference"; the labels Allamah and Ayatollah are in use for Twelver clerics.

Islamists

[edit]Islamist Shia (Persian: تشیع اخوانی) is a new denomination within Twelver Shia Islam greatly inspired by the political ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood and mysticism of Ibn Arabi. It sees Islam as a political system and differs from the other mainstream Usuli and Akhbari groups in favoring the idea of the establishment of an Islamic state in Occultation under the rule of the 12th Imam.[142][143] Hadi Khosroshahi was the first person to identify himself as ikhwani (Islamist) Shia Muslim.[144]

Because of the concept of the hidden Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, Shia Islam is inherently secular in the age of Occultation, therefore Islamist Shia Muslims had to borrow ideas from Sunnī Islamists and adjust them in accordance with the doctrine of Shia Islam.[145] Its foundations were laid during the Persian Constitutional Revolution at the start of 20th century in Qajar Empire (1905–1911), when Fazlullah Nouri supported the Persian king Ahmad Shah Qajar against the will of Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, the Usuli marjaʿ of the time.[146]

Ismāʿīlī

[edit]Ismāʿīlīs, otherwise known as Sevener, derive their name from their acceptance of Ismāʿīl ibn Jaʿfar as the divinely appointed spiritual successor (Imam) to Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the 6th Shia Imam, wherein they differ from the Twelvers, who recognize Mūsā al-Kāẓim, younger brother of Ismāʿīl, as the true Imam.

After the death or Occultation of Muhammad ibn Imam Ismāʿīl in the 8th century CE, the teachings of Ismāʿīlīsm further transformed into the belief system as it is known today, with an explicit concentration on the deeper, esoteric meaning (bāṭin) of the Islamic faith. With the eventual development of Twelver Shia Islam into the more literalistic (zahīr) oriented Akhbari and later Usuli schools of thought, Shia Islam further developed in two separate directions: the metaphorical Ismāʿīlī group focusing on the mystical path and nature of God and the divine manifestation in the personage of the "Imam of the Time" as the "Face of God", with the more literalistic Twelver group focusing on divine law (sharī'ah) and the deeds and sayings (sunnah) attributed to Muhammad and his successors (the Ahl al-Bayt), who as A'immah were guides and a light (nūr) to God.[147]

Though there are several subsects amongst the Ismāʿīlīs, the term in today's vernacular generally refers to the Shia Imami Ismāʿīlī Nizārī community, often referred to as the Ismāʿīlīs by default, who are followers of the Aga Khan and the largest group within Ismāʿīlīsm. Another Shia Imami Ismāʿīlī community are the Dawudi Bohras, led by a Da'i al-Mutlaq ("Unrestricted Missionary") as representative of a hidden Imam. While there are many other branches with extremely differing exterior practices, much of the spiritual theology has remained the same since the days of the faith's early Imams. In recent centuries, Ismāʿīlīs have largely been an Indo-Iranian community,[148] but they can also be found in India, Pakistan, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia,[149] Yemen, Jordan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, East and South Africa, and in recent years several Ismāʿīlīs have emigrated to China,[150] Western Europe (primarily in the United Kingdom), Australia, New Zealand, and North America.[151]

Ismāʿīlī Imams

[edit]In the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī interpretation of Shia Islam, the Imam is the guide and the intercessor between humans and God, and the individual through whom God is recognized. He is also responsible for the esoteric interpretation of the Quran (taʾwīl). He is the possessor of divine knowledge and therefore the "Prime Teacher". According to the "Epistle of the Right Path", a Persian Ismāʿīlī prose text from the post-Mongol period of Ismāʿīlī history, by an anonymous author, there has been a chain of Imams since the beginning of time, and there will continue to be an Imam present on the Earth until the end of time. The worlds would not exist in perfection without this uninterrupted chain of Imams. The proof (hujja) and gate (bāb) of the Imam are always aware of his presence and are witness to this uninterrupted chain.[152]

After the death of Ismāʿīl ibn Jaʿfar, many Ismāʿīlīs believed that one day the eschatological figure of Imam Mahdi, whom they believed to be Muhammad ibn Imam Ismāʿīl, would return and establish an age of justice. One group included the violent Qarmatians, who had a stronghold in Bahrain. In contrast, some Ismāʿīlīs believed the Imamate did continue, and that the Imams were in Occultation and still communicated and taught their followers through a network of Da'i ("Missionaries").

In 909 CE, Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah, a claimant to the Ismāʿīlī Imamate, established the Fatimid Caliphate. During this period, three lineages of Imams were formed. The first branch, known today as the Druze, began with Al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh.[153] Born in 985 CE, he ascended as ruler at the age of eleven. When in 1021 CE his mule returned without him, soaked in blood, a religious group that was forming in his lifetime broke off from mainstream Ismāʿīlīsm and did not acknowledge his successor.[153]

Later to be known as the Druze, they believe Al-Ḥākim to be God incarnate[154] and the prophesied Mahdi on Earth, who would one day return and bring justice to the world.[155] The Druze faith further split from Ismāʿīlīsm as it developed into a distinct monotheistic Abrahamic religion and ethno-religious group with its own unique doctrines,[153] and finally separated from both Ismāʿīlīsm and Islam altogether.[153] Thus, the Druze do not identify themselves as Muslims,[153] and are not considered as such by Muslims either.[153][156][157][158][159]

The second split occurred between Nizārī and Musta‘lī Ismāʿīlīs following the death of Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah in 1094 CE. His rule was the longest of any caliph in any Islamic empire. Upon his death, his sons, Nizār (the older) and Al-Musta‘lī (the younger), fought for political and spiritual control of the dynasty. Nizār was defeated and jailed, but according to the Nizārī tradition his son escaped to Alamut, where the Iranian Ismāʿīlī had accepted his claim.[160] From here on, the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī community has continued with a present, living Imam.

The Musta‘lī Ismāʿīlīs split between the Ṭayyibi and the Ḥāfiẓi; Ṭayyibi Ismāʿīlīs, also known as "Bohras", are further divided between Dawudi Bohras, Sulaymani Bohras, and Alavi Bohras. The former denomination claims that At-Tayyib Abi l-Qasim, son of Al-Amir bi-Ahkami l-Lah, and the Imams following him went into a period of anonymity (Dawr-e-Satr) and appointed a Da'i al-Mutlaq ("Unrestricted Missionary") to guide the community, in a similar manner as the Ismāʿīlīs had lived after the death of Muhammad ibn Imam Ismāʿīl. The latter denomination claims that the ruling Fatimid caliph was the Imam, and they died out with the fall of the Fatimid Empire.

Pillars

[edit]Ismāʿīlīs have categorized their practices which are known as seven pillars:

|

Contemporary leadership

[edit]The Nizārīs place importance on a scholarly institution because of the existence of a present Imam. The Imam of the Age defines the jurisprudence, and his guidance may differ with Imams previous to him because of different times and circumstances. For Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs, the current Imam is Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV. The Nizārī line of Imams has continued to this day as an uninterrupted chain.

Divine leadership has continued in the Bohra branch through the institution of the "Missionary" (Da'i). According to the Bohra tradition, before the last Imam, At-Tayyib Abi l-Qasim, went into seclusion, his father, the 20th Al-Amir bi-Ahkami l-Lah, had instructed Al-Hurra Al-Malika the Malika (Queen consort) in Yemen to appoint a vicegerent after the seclusion—the Da'i al-Mutlaq ("Unrestricted Missionary"), who as the Imam's vicegerent has full authority to govern the community in all matters both spiritual and temporal while the lineage of Musta‘lī-Ṭayyibi Imams remains in seclusion (Dawr-e-Satr). The three branches of Musta‘lī Ismāʿīlīs (Dawudi Bohras, Sulaymani Bohras, and Alavi Bohras) differ on who the current "Unrestricted Missionary" is.[citation needed]

Zaydī

[edit]

Zaydism, otherwise known as Zaydiyya or as Zaydi Shia Islam, is a branch of Shia Islam named after Zayd ibn ʿAlī. Followers of the Zaydī school of jurisprudence are called Zaydīs or occasionally Fivers. However, there is also a group called Zaydī Wāsiṭīs who are Twelvers (see below). Zaydīs constitute roughly 42–47% of the population of Yemen.[161][162]

Doctrine

[edit]The Zaydīs, Twelvers, and Ismāʿīlīs all recognize the same first four Imams; however, the Zaydīs consider Zayd ibn ʿAlī as the 5th Imam. After the time of Zayd ibn ʿAlī, the Zaydīs believed that any descendant (Sayyid) of Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī or Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī could become the next Imam, after fulfilling certain conditions.[163] Other well-known Zaydī Imams in history were Yahya ibn Zayd, Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya, and Ibrahim ibn Abdullah.

The Zaydī doctrine of Imamah does not presuppose the infallibility of the Imam, nor the belief that the Imams are supposed to receive divine guidance. Moreover, Zaydīs do not believe that the Imamate must pass from father to son but believe it can be held by any Sayyid descended from either Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī or Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī (as was the case after the death of the former). Historically, Zaydīs held that Zayd ibn ʿAlī was the rightful successor of the 4th Imam since he led a rebellion against the Umayyads in protest of their tyranny and corruption. Muhammad al-Baqir did not engage in political action, and the followers of Zayd ibn ʿAlī maintained that a true Imam must fight against corrupt rulers.

Jurisprudence

[edit]In matters of Islamic jurisprudence, Zaydīs follow the teachings of Zayd ibn ʿAlī, which are documented in his book Majmu'l Fiqh (in Arabic: مجموع الفِقه). Al-Ḥādī ila'l-Ḥaqq Yaḥyā, the first Zaydī Imam and founder of the Zaydī State in Yemen, is regarded as the codifier of Zaydī jurisprudence, and as such most Zaydī Shias today are known as Hadawis.

Timeline

[edit]The Idrisids (Arabic: الأدارسة) were Arab[164] Zaydī Shias[165] whose dynasty, named after its first sultan, Idris I, ruled in the western Maghreb from 788 to 985 CE. Another Zaydī State was established in the region of Gilan, Deylaman, and Tabaristan (northern Iran) in 864 CE by the Alavids;[166] it lasted until the death of its leader at the hand of the Samanids in 928 CE. Roughly forty years later, the Zaydī State was revived in Gilan and survived under Hasanid leaders until 1126 CE. Afterwards, from the 12th to 13th centuries, the Zaydī Shias of Deylaman, Gilan, and Tabaristan then acknowledged the Zaydī Imams of Yemen or rival Zaydī Imams within Iran.[167]

The Buyids were initially Zaydī Shias,[168] as were the Banu Ukhaidhir rulers of al-Yamama in the 9th and 10th centuries.[169] The leader of the Zaydī community took the title of caliph; thus, the ruler of Yemen was known by this title. Al-Hadi Yahya bin al-Hussain bin al-Qasim ar-Rassi, a descendant of Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī, founded the Zaydī Imamate at Sa'dah in 893–897 CE, and the Rassid dynasty continued to rule over Yemen until the middle of the 20th century, when the republican revolution of 1962 deposed the last Zaydī Imam. See: Arab Cold War.

The founding Zaydī branch in Yemen was the Jarudiyya. With increasing interaction with the Ḥanafī and Shāfiʿī schools of Sunnī jurisprudence, there was a shift from the Jarudiyya group to the Sulaimaniyya, Tabiriyya, Butriyya, and Salihiyya.[170] Zaydī Shias form the second dominant religious group in Yemen. Currently, they constitute about 40–45% of the population in Yemen; Jaʿfaris and Ismāʿīlīs constitute the 2–5%.[171] In Saudi Arabia there are over 1 million Zaydī Shias, primarily in the western provinces.

Currently, the most prominent Zaydī political movement is the Houthi movement in Yemen,[172] known by the name of Shabab al-Mu'mineen ("Believing Youth") or Ansar Allah ("Partisans of God").[173] In 2014–2015, Houthis took over the Yemeni government in Sana'a, which led to the fall of the Saudi Arabian-backed government of Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi.[172][173][174] Houthis and their allies gained control of a significant part of Yemen's territory, and resisted the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen seeking to restore Hadi in power.[172][173] (See: Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict). Both the Houthis and the Saudi Arabian-led coalition were being attacked by the Sunnī Islamist militant group and Salafi-jihadist terrorist organization ISIL/ISIS/IS/Daesh.[175][176][177][178][179][180]

Persecution of Shia Muslims

[edit]

The history of Shia–Sunni relations has often involved religious discrimination, persecution, and violence, dating back to the earliest development of the two competing sects. At various times throughout the history of Islam, Shia groups and minorities have faced persecution perpetrated by Sunnī Muslims.[181][182][183][184]

Militarily established and holding control over the Umayyad government, many Sunnī rulers perceived the Shias as a threat—both to their political and religious authority.[185] The Sunnī rulers under the Umayyad dynasty sought to marginalize the Shia minority, and later the Abbasids turned on their Shia allies and imprisoned, persecuted, and killed them. The persecution of Shia Muslims throughout history by their Sunnī co-religionists has often been characterized by brutal and genocidal acts. Comprising only about 10–15% of the global Muslim population,[92] Shia Muslims remain a marginalized community to this day in many Sunnī-dominant Arab countries, and are denied the rights to practice their religion and freely organize.[186]

In 1514, the Ottoman sultan Selim I (1512–1520) ordered the massacre of 40,000 Alevis and Bektashi (Anatolian Shia Muslims).[187] According to Jalal Al-e-Ahmad, "Sultan Selim I carried things so far that he announced that the killing of one Shia had as much otherworldly reward as killing 70 Christians."[188] In 1802, the Al Saud-Wahhabi armies of the Ikhwan from the First Saudi State (1727–1818) attacked and sacked the city of Karbala, the Shia shrine in Najaf (eastern region of Iraq) that commemorates the martyrdom and death of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī.[189]

During the rule of Saddam Hussein's Ba'athist Iraq, Shia political activists were arrested, tortured, expelled or killed, as part of a crackdown launched after an assassination attempt against Iraq's Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz in 1980.[190][191] In March 2011, the Malaysian government declared Shia Islam a "deviant" sect and banned Shia Muslims from promoting their faith to other Muslims, but left them free to practice it themselves privately.[192][193]

The most recent campaign of anti-Shia oppression was the Islamic State organization's persecution of Shias in its territories in Northern Iraq,[177][194][178][195] which occurred alongside the persecution of various religious groups and the genocide of Yazidis by the same organization.[177][178][179][180]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˈʃiːə/ /ˈɪzlɑːm, ˈɪzlæm/

- ^ A 2019 Council on Foreign Relations article states: "Nobody really knows the size of the Shia population in Nigeria. Credible estimates that its numbers range between 2 and 3 percent of Nigeria's population, which would amount to roughly four million."[124] A 2019 BBC News article said that "Estimates of [Nigerian Shia] numbers vary wildly, ranging from less than 5% to 17% of Nigeria's Muslim population of about 100 million."[125]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Armajani, Jon (2020). Shia Islam and Politics: Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon. Lanham, MD: Lexington. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-7936-2136-8.

- ^ See

- "Shiʿi". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

In the early 21st century some 10–13 percent of the world's 1.6 billion Muslims were Shiʿi.

- "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

The Pew Forum's estimate of the Shia population (10–13%) is in keeping with previous estimates, which generally have been in the range of 10–15%. Some previous estimates, however, have placed the number of Shias at nearly 20% of the world's Muslim population.

- "Shia". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Archived from the original on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

Shi'a Islam is the second largest branch of the tradition, with up to 200 million followers who comprise around 15% of all Muslims worldwide...

- Jalil Roshandel (2011). Iran, Israel and the United States. Praeger Security International. p. 15. ISBN 9780313386985.

The majority of the world's Islamic population, which is Sunni, accounts for over 75 percent of the Islamic population; the other 10 to 20 percent is Shia.

- "Shiʿi". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "وثيقة بحرينية: الشيعة أقل من النصف". Al Jazeera. 4 July 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

كشفت وثيقة بحرينية رسمية حديثة أن نسبة المواطنين السنة من إجمالي مواطني البلاد تعادل 51%، في حين توقفت نسبة الطائفة الشيعية عند 49%

[A recent official Bahraini document revealed that the percentage of Sunni citizens out of the country’s total citizens is 51%, while the percentage of the Shiite community stopped at 49%..] - ^ Armajani 2020, pp. 1–3.

- ^ a b c d The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th ed., Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998, ISBN 0-85229-663-0, Vol. 10, p. 738

- ^ Duncan S. Ferguson (2010). Exploring the Spirituality of the World Religions: The Quest for Personal, Spiritual and Social Transformation. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4411-4645-8.

- ^ Wehr, Hans. "Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic" (4th ed.). p. 598.

- ^ "Difference Between The Meaning Of Shia And Shiite? However the term Shiite is being used less and is considered less proper than simply using the term "Shia"". English forums. 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Ṭabataba'i 1977, p. 34

- ^ a b c d e f g Foody, Kathleen (September 2015). Jain, Andrea R. (ed.). "Interiorizing Islam: Religious Experience and State Oversight in the Islamic Republic of Iran". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 83 (3). Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Academy of Religion: 599–623. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfv029. eISSN 1477-4585. ISSN 0002-7189. JSTOR 24488178. LCCN sc76000837. OCLC 1479270.

For Shiʿi Muslims, Muhammad not only designated ʿAlī as his friend, but appointed him as his successor—as the "lord" or "master" of the new Muslim community. ʿAlī and his descendants would become known as the Imams, divinely guided leaders of the Shiʿi communities, sinless, and granted special insight into the Qurʾanic text. The theology of the Imams that developed over the next several centuries made little distinction between the authority of the Imams to politically lead the Muslim community and their spiritual prowess; quite to the contrary, their right to political leadership was grounded in their special spiritual insight. While in theory, the only just ruler of the Muslim community was the Imam, the Imams were politically marginal after the first generation. In practice, Shiʿi Muslims negotiated varied approaches to both interpretative authority over Islamic texts and governance of the community, both during the lifetimes of the Imams themselves and even more so following the disappearance of the twelfth and final Imam in the ninth century.

- ^ Sobhani & Shah-Kazemi 2001, p. 97

- ^ Sobhani & Shah-Kazemi 2001, p. 98

- ^ Vaezi, Ahmad (2004). Shia political thought. London: Islamic Centre of England. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-904934-01-1. OCLC 59136662.

- ^ Cornell 2007, p. 218

- ^ "Shiʻite Islam", by Allamah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i, translated by Sayyid Husayn Nasr, State University of New York Press, 1975, p. 24

- ^ Dakake (2008), pp. 1–2

- ^ In his "Mutanabbi devant le siècle ismaëlien de l'Islam", in Mém. de l'Inst Français de Damas, 1935, p.

- ^ See: Lapidus p. 47, Holt p. 72

- ^ Francis Robinson, Atlas of the Islamic World, p. 23.

- ^ Jafri, S.H. Mohammad. "The Origin and Early Development of Shiʻa Islam", Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-19-579387-1

- ^ a b c d e f g Martin, Richard C. (2003). "Shīʿa". Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. New York: Macmillan reference USA. pp. 621–624. ISBN 978-0-02-865603-8.

- ^ Newman, Andrew J. Shiʿi. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Esposito, John. "What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam". Oxford University Press, 2002 | ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 40

- ^ "From the article on Shii Islam in Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Oxfordislamicstudies.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ a b Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (2014). "Ghadīr Khumm". In Kate Fleet; Gundrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Ghadīr Khumm. Encyclopaedia of Islam Three. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27419.

- ^ Olawuyi, Toyib (2014). On the Khilafah of Ali over Abu Bakr. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4928-5884-3. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^ "The Shura Principle in Islam – by Sadek Sulaiman". www.alhewar.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Sunnis and Shia: Islam's ancient schism". BBC News. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, Wendy Doniger, Consulting Editor, Merriam-Webster, Inc., Springfield, MA 1999, ISBN 0-87779-044-2, LoC: BL31.M47 1999, p. 525

- ^ a b c "Esposito, John. "What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam" Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 46

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th ed., Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998, ISBN 0-85229-663-0, Vol. 10, p. tid738

- ^ ""Solhe Emam Hassan"-Imam Hassan Sets Peace". Archived from the original on 11 March 2013.

- ^ تهذیب التهذیب. p. 271.

- ^ Madelung, Wilfred (2003). "Ḥasan b. ʿAli b. Abi Ṭāleb". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Discovering Islam: making sense of Muslim history and society (2002) Akbar S. Ahmed

- ^ Mustafa, Ghulam (1968). Religious trends in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. p. 11. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

Similarly, swords were also placed on the Idols, as it is related that Harith b. Abi Shamir, the Ghassanid king, had presented his two swords, called Mikhdham and Rasub, to the image of the goddess, Manat....to note that the famous sword of Ali, the fourth caliph, called Dhu-al-Fiqar, was one of these two swords

- ^ "Lesson 13: Imam's Traits". Al-Islam.org. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015.

- ^ Goldziher, I.; van Arendonk, C.; Tritton, A.S. (2012). "Ahl al- Bayt". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Ahl al-BMatt. Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_0378.

- ^ a b "امامت از منظر متکلّمان شیعی و فلاسفه اسلامی". پرتال جامع علوم انسانی (in Persian). Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b Nasr (1979), p. 10

- ^ a b Momen 1985, p. 174

- ^ عسکری, سید مرتضی. ولایت علی در قرآن کریم و سنت پیامبر، مرکز فرهنگی انتشاراتی منیر، چاپ هفتم.

- ^ Corbin 1993, pp. 45–51

- ^ Nasr (1979), p. 15

- ^ a b Gleave, Robert (2004). "Imamate". Encyclopaedia of Islam and the Muslim world; vol.1. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-865604-5.

- ^ "نقد و بررسى گرایش ایلخانان به اسلام و تشیّع". پرتال جامع علوم انسانی (in Persian). Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ "The Five Kingdoms of the Bahmani Sultanate". orbat.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ^ Ansari, N.H. Bahmanid Dynasty. Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2006.

- ^ Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- ^ Chodorow, Stanley; Knox, MacGregor; Shirokauer, Conrad; Strayer, Joseph R.; Gatzke, Hans W. (1994). The Mainstream of Civilization. Harcourt Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-15-501197-7.

The architect of his military system was a general named Jawhar, an islamicized Greek slave who had led the conquest of North Africa and then of Egypt

- ^ Fossier, Robert; Sondheimer, Janet; Airlie, Stuart; Marsack, Robyn (1997). The Cambridge illustrated history of the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-521-26645-1.

When the Sicilian Jawhar finally entered Fustat in 969 and the following year founded the new dynastic capital, Cairo, 'The Victorious', the Fatimids ...

- ^ Saunders, John Joseph (1990). A History of Medieval Islam. Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-415-05914-5.

Under Muʼizz (955-975) the Fatimids reached the height of their glory, and the universal triumph of Isma ʻilism appeared not far distant. The fourth Fatimid Caliph is an attractive character: humane and generous, simple and just, he was a good administrator, tolerant and conciliatory. Served by one of the greatest generals of the age, Jawhar al-Rumi, a former Greek slave, he took fullest advantage of the growing confusion in the Sunnite world.

- ^ a b Masters, Bruce (2009). "Baghdad". In Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Facts On File. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1. LCCN 2008020716. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Stanford J. Shaw; Ezel Kural Shaw (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Francis Robinson, Atlas of the Muslim World, p. 49.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 123

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 130, 191

- ^ "Druze and Islam". americandruze.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ "Ijtihad in Islam". AlQazwini.org. Archived from the original on 2 January 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 15

- ^ a b Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (20 July 2005). Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). "Shiʻite Doctrine". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of the Middle East". Mideastweb.org. 14 November 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ "اضافه شدن نام حضرت علی (ع) به شهادتین". fa. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b Dabashi (2006). Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundatation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Transaction Publishers. p. 463. ISBN 978-1412839723.

- ^ Francis Robinson, Atlas of the Muslim World, p. 47.

- ^ "Shīʿite". Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Quran 33:33

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 155

- ^ Corbin (1993), pp. 48, 49

- ^ Corbin (1993), p. 48

- ^ "How do Sunnis and Shias differ theologically?". BBC. 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014.

- ^ Nasr, Sayyed Hossein. Expectation of the Millennium: Shiìsm in History, State University of New York Press, 1989, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-88706-843-0

- ^ "Compare Shia and Sunni Islam". ReligionFacts. 17 March 2004. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ "The Complete Idiot's Guide to World Religions", Brandon Toropov, Father Luke Buckles, Alpha; 3rd ed., 2004, ISBN 978-1-59257-222-9, p. 135

- ^ Shiʻite Islam, by Allamah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i (1979), pp. 41–44 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c d Al-Kulayni, Abu Jaʼfar Muhammad ibn Yaʼqub (2015). Kitab al-Kafi. South Huntington, NY: The Islamic Seminary Inc. ISBN 978-0-9914308-6-4.[page needed]

- ^ Allamah Muhammad Rida Al Muzaffar (1989). The faith of Shia Islam. Ansariyan Qum. p. 1.

- ^ "The Beliefs of Shia Islam – Chapter 1". Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ^ Sanders, Paula (1994). Ritual, politics, and the city in Fatimid Cairo. SUNY Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0791417812.

- ^ Trawicky, Bernard; Wilhelme Gregory, Ruth (2002). Anniversaries and holidays. American Library Association. p. 233. ISBN 978-0838910047.

- ^ "Lady Fatima inspired women of Iran to emerge as an extraordinary force". 18 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (2 June 2007). "Inside Iran's Holy Money Machine". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "Karbala and Najaf: Shia holy cities". 20 April 2003.

- ^ Escobar, Pepe (24 May 2002). "Knocking on heaven's door". Central Asia/Russia. Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 3 June 2002. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

according to a famous hadith... 'our sixth imam, Imam Sadeg, says that we have five definitive holy places that we respect very much. The first is Mecca... second is Medina... third... is in Najaf. The fourth... in Kerbala. The last one belongs to... Qom.'

- ^ Louėr, Laurence (2008). Transnational Shia politics: religious and political networks in the Gulf. Columbia University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0231700405.

- ^ Dabrowska, Karen; Hann, Geoff (2008). Iraq Then and Now: A Guide to the Country and Its People. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 239. ISBN 978-1841622439. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017.

- ^ a b Tsadik, Daniel (1 October 2010), "Najāsat", Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, Brill, retrieved 8 January 2024

- ^ a b Litvak, Meir (2017). Constructing nationalism in Iran: from the Qajars to the Islamic Republic. Routledge studies in modern history. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-138-21322-7.

- ^ a b Moreen, Vera B. (1 October 2010), "Shiʽa and the Jews", Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, Brill, retrieved 8 January 2024

- ^ "Jews and Wine in Shiite Iran – Some Observations on the Concept of Religious Impurity". Association for Iranian Studies. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "Jurisprudence and Law – Islam: Reorienting the Veil". University of North Carolina. 2009.

- ^ a b c "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

The Pew Forum's estimate of the Shia population (10–13%) is in keeping with previous estimates, which generally have been in the range of 10–15%.

- ^ "Shīʿite". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

In the early 21st century some 10–13 percent of the world's 1.6 billion Muslims were Shiʿi.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

Of the total Muslim population, 10–13% are Shia Muslims and 87–90% are Sunni Muslims. Most Shias (between 68% and 80%) live in just four countries: Iran, Pakistan, India and Iraq.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009). Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population (PDF). Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 277

- ^ a b "Foreign Affairs – When the Shiites Rise – Vali Nasr". Mafhoum.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Quick guide: Sunnis and Shias". BBC News. 11 December 2006. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008.

- ^ Atlas of the Middle East (Second ed.). Washington, DC: National Geographic. 2008. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1-4262-0221-6.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2010". U.S. Government Department of State. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report for 2012". US State Department. 2012.

- ^ "The New Middle East, Turkey, and the Search for Regional Stability" (PDF). Strategic Studies Institute. April 2008. p. 87. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2015.

- ^ Shankland, David (2003). The Alevis in Turkey: The Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1606-7.

- ^ "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

Religion: The overwhelming majority of the population (96.3 percent) is Muslim, of whom approximately 95 percent are Sunni and 5 percent Shia.

- ^ "Shia women too can initiate divorce" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

Religion: Virtually the entire population is Muslim. Between 80 and 85 percent of Muslims are Sunni and 15 to 19 percent, Shia.

- ^ "Afghanistan". Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Factbook on Afghanistan. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

Religions: Sunni Muslim 80%, Shia Muslim 19%, other 1%

- ^ Al Jazeera: [], 1973, retrieved 14 February 2021

- ^ Joyce, Miriam (2012). Bahrain from the Twentieth Century to the Arab Spring. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-137-03178-5.

- ^ al-Qudaihi, Anees (24 March 2009). "Saudi Arabia's Shia press for rights". BBC Arabic Service. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ Merrick, Jane; Sengupta, Kim (20 September 2009). "Yemen: The land with more guns than people". The Independent. London. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ^ Sharma, Hriday (30 June 2011). "The Arab Spring: The Initiating Event for a New Arab World Order". E-international Relations. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020.

In Yemen, Zaidists, a Shia offshoot, constitute 30% of the total population

- ^ Leonard Leo. International Religious Freedom (2010): Annual Report to Congress. Diane Publishing. pp. 261–. ISBN 978-1-4379-4439-6. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Paul Ohia (16 November 2010). "Nigeria: 'No Settlement With Iran Yet'". This Day. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- ^ Charton-Bigot, Helene; Rodriguez-Torres, Deyssi (2010). Nairobi Today: the Paradox of a Fragmented City. African Books Collective. p. 239. ISBN 978-9987080939.

- ^ Heinrich Matthée (2008). Muslim Identities and Political Strategies: A Case Study of Muslims in the Greater Cape Town Area of South Africa, 1994–2000. kassel university press GmbH. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-3-89958-406-6. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- ^ Yasurō Hase; Hiroyuki Miyake; Fumiko Oshikawa (2002). South Asian migration in comparative perspective, movement, settlement and diaspora. Japan Center for Area Studies, National Museum of Ethnology. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Pakistan". US Department of State. 2023.

- ^ Reynolds, James (12 August 2012). "Why Azerbaijan is closer to Israel than Iran". BBC.

- ^ Umutlu, Ayseba. "Islam's gradual resurgence in post-Soviet Azerbaijan".

- ^ a b Bedford, Sofie (2016). Ismayilov, Murad; Graham, Norman A. (eds.). Turkish–Azerbaijani Relations: One Nation – Two States?. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 978-1138650817.

- ^ Massoud, Waheed (6 December 2011). "Why have Afghanistan's Shias been targeted now?". BBC.

- ^ "Lebanon". CIA World Factbook. 2020.

- ^ a b Campbell, John (10 July 2019). "More Trouble Between Nigeria's Shia Minority and the Police". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ Tangaza, Haruna Shehu (5 August 2019). "Islamic Movement in Nigeria: The Iranian-inspired Shia group". BBC.

- ^ "2018 Report on International Religious Freedom: Kuwait". Office of International Religious Freedom, United States Department of State.

- ^ Aswad, B. and Abowd, T., 2013. Arab Americans. Race and Ethnicity: The United States and the World, pp. 272–301.

- ^ Erlich, Reese (4 August 2015). "Mitigating Sunni-Shia conflict in 'the world's most charming police state'". Agence France-Presse.

- ^ Newman, Andrew J. (2013). "Introduction". Twelver Shiism: Unity and Diversity in the Life of Islam, 632 to 1722. Edinburgh University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7486-7833-4. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Guidère, Mathieu (2012). Historical Dictionary of Islamic Fundamentalism. Scarecrow Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-8108-7965-2.

- ^ Tabataba'i (1979), p. 76

- ^ God's rule: the politics of world religions, p. 146, Jacob Neusner, 2003

- ^ Esposito, John. What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam, Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 40

- ^ Cornell 2007, p. 237

- ^ "Esposito, John. "What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam" Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 45.

- ^ "Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan – Presidential Library – Religion" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2011.

- ^ Esposito, John. "What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam" Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 45

- ^ "Challenges For Saudi Arabia Amidst Protests in the Gulf – Analysis". Eurasia Review. 25 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012.

- ^ a b Richter, Joanne (2006). Iran: the Culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 7. ISBN 978-0778791423.