Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dharma

View on Wikipedia

Dharma (/ˈdɑːrmə/; Sanskrit: धर्म, pronounced [dʱɐrmɐ] ⓘ) is a key concept in various Indian religions. The term dharma does not have a single, clear translation and conveys a multifaceted idea. Etymologically, it comes from the Sanskrit dhr-, meaning to hold or to support, thus referring to law that sustains things—from one's life to society, and to the Universe at large. In its most commonly used sense, dharma refers to an individual's moral responsibilities or duties; the dharma of a farmer differs from the dharma of a soldier, thus making the concept of dharma dynamic. As with the other components of the Puruṣārtha, the concept of dharma is pan-Indian. The antonym of dharma is adharma.

In Hinduism, dharma denotes behaviour that is considered to be in accord with Ṛta—the "order and custom" that makes life and universe possible.[note 1] This includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living" according to the stage of life or social position. Dharma is believed to have a transtemporal validity, and is one of the Puruṣārtha. The concept of dharma was in use in the historical Vedic religion (1500–500 BCE), and its meaning and conceptual scope has evolved over several millennia.

In Buddhism, dharma (Pali: dhamma) refers to the teachings of the Buddha and to the true nature of reality (which the teachings point to). In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for specific "phenomena" and for the ultimate truth.[note 2] Dharma in Jainism refers to the teachings of Tirthankara (Jina) and the body of doctrine pertaining to purification and moral transformation. In Sikhism, dharma indicates the path of righteousness, proper religious practices, and performing moral duties.

Etymology

[edit]

The word dharma (/ˈdɑːrmə/)[3] has roots in the Sanskrit dhr-, which means to hold or to support, and is related to Latin firmus (firm, stable).[4] From this, it takes the meaning of "what is established or firm", and hence "law". It is derived from an older Vedic Sanskrit n-stem dharman-, with a literal meaning of "bearer, supporter", in a religious sense conceived as an aspect of Rta.[5]

In the Rigveda, the word appears as an n-stem, dhárman-, with a range of meanings encompassing "something established or firm" (in the literal sense of prods or poles). Figuratively, it means "sustainer" and "supporter" (of deities). It is semantically similar to the Greek themis ("fixed decree, statute, law").[6]

In Classical Sanskrit, and in the Vedic Sanskrit of the Atharvaveda, the stem is thematic: dhárma- (Devanagari: धर्म). In Prakrit and Pali, it is rendered dhamma. In some contemporary Indian languages and dialects it alternatively occurs as dharm.

In the 3rd century BCE the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka translated dharma into Greek and Aramaic and he used the Greek word eusebeia (εὐσέβεια, piety, spiritual maturity, or godliness) in the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription and the Kandahar Greek Edicts.[7] In the former, he used the Aramaic word קשיטא (qšyṭ’; truth, rectitude).[8]

Definition

[edit]Dharma is a concept of central importance in Indian philosophy and Indian religions.[15] It has multiple meanings in Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism.[16] It is difficult to provide a single concise definition for dharma, as the word has a long and varied history and straddles a complex set of meanings and interpretations.[17] There is no equivalent single-word synonym for dharma in western languages.[18]

There have been numerous, conflicting attempts to translate ancient Sanskrit literature with the word dharma into German, English and French. The concept, claims Paul Horsch, has caused exceptional difficulties for modern commentators and translators.[19] For example, while Grassmann's translation of Rig-Veda identifies seven different meanings of dharma,[20] Karl Friedrich Geldner in his translation of the Rig-Veda employs 20 different translations for dharma, including meanings such as "law", "justice", "righteousness", "order", "duty", "custom", "quality", and "model", among others.[19] However, the word dharma has become a widely accepted loanword in English, and is included in all modern unabridged English dictionaries.

The term dharma derives from the Sanskrit root "dhr̥", which means "to support, hold, or bear". It is the thing that regulates the course of change by not participating in change, but that principle which remains constant.[21] Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, the widely cited resource for definitions and explanation of Sanskrit words and concepts of Hinduism, offers[22] numerous definitions of the word dharma, such as that which is established or firm, steadfast decree, statute, law, practice, custom, duty, right, justice, virtue, morality, ethics, religion, religious merit, good works, nature, character, quality, property. Yet, each of these definitions is incomplete, while the combination of these translations does not convey the total sense of the word. In common parlance, dharma means "right way of living" and "path of rightness".[21] Dharma also has connotations of order, and when combined with the word sanātana, it can also be described as eternal truth.[23]

The meaning of the word dharma depends on the context, and its meaning has evolved as ideas of Hinduism have developed through history. In the earliest texts and ancient myths of Hinduism, dharma meant cosmic law, the rules that created the universe from chaos, as well as rituals; in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas and the Epics, the meaning became refined, richer, and more complex, and the word was applied to diverse contexts.[24] In certain contexts, dharma designates human behaviours considered necessary for order of things in the universe, principles that prevent chaos, behaviours and action necessary to all life in nature, society, family as well as at the individual level.[1][24][25][note 1] Dharma encompasses ideas such as duty, rights, character, vocation, religion, customs and all behaviour considered appropriate, correct or morally upright.[26] For further context, the word varnasramdharma is often used in its place, defined as dharma specifically related to the stage of life one is in.[27] The concept of Dharma is believed to have a transtemporal validity.[28]

The antonym of dharma is adharma (Sanskrit: अधर्म),[29] meaning that which is "not dharma". As with dharma, the word adharma includes and implies many ideas; in common parlance, adharma means that which is against nature, immoral, unethical, wrong or unlawful.[30]

In Buddhism, dharma incorporates the teachings and doctrines of the founder of Buddhism, the Buddha.

History

[edit]According to Pandurang Vaman Kane, author of the book History of Dharmaśāstra, the word dharma appears at least fifty-six times in the hymns of the Rigveda, as an adjective or noun. According to Paul Horsch, the word dharma has its origin in Vedic Hinduism.[19] The hymns of the Rigveda claim Brahman created the universe from chaos, they hold (dhar-) the earth and sun and stars apart, they support (dhar-) the sky away and distinct from earth, and they stabilise (dhar-) the quaking mountains and plains.[19][31]

The Deities, mainly Indra, then deliver and hold order from disorder, harmony from chaos, stability from instability – actions recited in the Veda with the root of word dharma.[24] In hymns composed after the mythological verses, the word dharma takes expanded meaning as a cosmic principle and appears in verses independent of deities. It evolves into a concept, claims Paul Horsch, that has a dynamic functional sense in Atharvaveda for example, where it becomes the cosmic law that links cause and effect through a subject.[19] Dharma, in these ancient texts, also takes a ritual meaning. The ritual is connected to the cosmic, and "dharmani" is equated to ceremonial devotion to the principles that deities used to create order from disorder, the world from chaos.[32]

Past the ritual and cosmic sense of dharma that link the current world to mythical universe, the concept extends to an ethical-social sense that links human beings to each other and to other life forms. It is here that dharma as a concept of law emerges in Hinduism.[33][34]

Dharma and related words are found in the oldest Vedic literature of Hinduism, in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, and the Epics; the word dharma also plays a central role in the literature of other Indian religions founded later, such as Buddhism and Jainism.[24] According to Brereton, Dharman occurs 63 times in Rig-veda; in addition, words related to Dharman also appear in Rig-veda, for example once as dharmakrt, 6 times as satyadharman, and once as dharmavant, 4 times as dharman and twice as dhariman.[35]

Indo-European parallels for "dharma" are known, but the only Iranian equivalent is Old Persian darmān, meaning "remedy". This meaning is different from the Indo-Aryan dhárman, suggesting that the word "dharma" did not play a major role in the Indo-Iranian period. Instead, it was primarily developed more recently under the Vedic tradition.[35]

It is thought that the Daena of Zoroastrianism, also meaning the "eternal Law" or "religion", is related to Sanskrit "dharma".[36] Ideas in parts overlapping to Dharma are found in other ancient cultures: such as Chinese Tao, Egyptian Maat, Sumerian Me.[21]

Eusebeia and dharma

[edit]

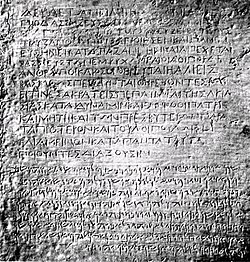

In the mid-20th century, an inscription of the Indian Emperor Asoka from the year 258 BCE was discovered in Afghanistan, the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription. This rock inscription contains Greek and Aramaic text. According to Paul Hacker,[37] on the rock appears a Greek rendering for the Sanskrit word dharma: the word eusebeia.[37]

Scholars of Hellenistic Greece explain eusebeia as a complex concept. Eusebia means not only to venerate deities, but also spiritual maturity, a reverential attitude toward life, and includes the right conduct toward one's parents, siblings and children, the right conduct between husband and wife, and the conduct between biologically unrelated people. This rock inscription, concludes Paul Hacker, suggests dharma in India, about 2300 years ago, was a central concept and meant not only religious ideas, but ideas of right, of good, of one's duty toward the human community.[37][38]

Rta, maya and dharma

[edit]The evolving literature of Hinduism linked dharma to two other important concepts: Ṛta and Māyā. Ṛta in Vedas is the truth and cosmic principle which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it.[39][40] Māyā in Rig-veda and later literature means illusion, fraud, deception, magic that misleads and creates disorder,[41] thus is contrary to reality, laws and rules that establish order, predictability and harmony. Paul Horsch suggests Ṛta and dharma are parallel concepts, the former being a cosmic principle, the latter being of moral social sphere;[19] while Māyā and dharma are also correlative concepts, the former being that which corrupts law and moral life, the later being that which strengthens law and moral life.[39][42]

Day proposes dharma is a manifestation of Ṛta, but suggests Ṛta may have been subsumed into a more complex concept of dharma, as the idea developed in ancient India over time in a nonlinear manner.[43] The following verse from the Rigveda is an example where rta and dharma are linked:

O Indra, lead us on the path of Rta, on the right path over all evils...

— RV 10.133.6

Hinduism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Dharma is an organising principle in Hinduism that applies to human beings in solitude, in their interaction with human beings and nature, as well as between inanimate objects, to all of cosmos and its parts.[21] It refers to the order and customs which make life and universe possible, and includes behaviours, rituals, rules that govern society, and ethics.[1][note 1] Hindu dharma includes the religious duties, moral rights and duties of each individual, as well as behaviours that enable social order, right conduct, and those that are virtuous.[44] Dharma, according to Van Buitenen,[45] is that which all existing beings must accept and respect to sustain harmony and order in the world. It is neither the act nor the result, but the natural laws that guide the act and create the result to prevent chaos in the world. It is innate characteristic, that makes the being what it is. It is, claims Van Buitenen, the pursuit and execution of one's nature and true calling, thus playing one's role in cosmic concert. In Hinduism, it is the dharma of the bee to make honey, of cow to give milk, of sun to radiate sunshine, of river to flow.[45] In terms of humanity, dharma is the need for, the effect of and essence of service and interconnectedness of all life.[21][37] This includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living".[46]

In its true essence, dharma means for a Hindu to "expand the mind". Furthermore, it represents the direct connection between the individual and the societal phenomena that bind the society together. In the way societal phenomena affect the conscience of the individual, similarly may the actions of an individual alter the course of the society, for better or for worse. This has been subtly echoed by the credo धर्मो धारयति प्रजा: meaning dharma is that which holds and provides support to the social construct.[citation needed]

In Hinduism, dharma generally includes various aspects:

- Sanātana Dharma, the eternal and unchanging principals of dharma.[47]

- Varṇ āśramā dharma, one's duty at specific stages of life or inherent duties.[48]

- Svadharma, one's own individual or personal duty.[49][50]

- Āpad dharma, dharma prescribed at the time of adversities.[50]

- Sadharana dharma, moral duties irrespective of the stages of life.[51][note 3]

- Yuga dharma, dharma which is valid for a yuga, an epoch or age as established by Hindu tradition and thus may change at the conclusion of its time.[16][53]

In Vedas and Upanishads

[edit]The history section of this article discusses the development of dharma concept in Vedas. This development continued in the Upanishads and later ancient scripts of Hinduism. In Upanishads, the concept of dharma continues as universal principle of law, order, harmony, and truth. It acts as the regulatory moral principle of the Universe. It is explained as law of righteousness and equated to satya (Sanskrit: सत्यं, truth),[19][54] in hymn 1.4.14 of Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, as follows:

Nothing is higher than dharma. The weak overcomes the stronger by dharma, as over a king. Truly that dharma is the Truth (Satya); Therefore, when a man speaks the Truth, they say, "He speaks the Dharma"; and if he speaks Dharma, they say, "He speaks the Truth!" For both are one.

— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4.xiv[19][54]

Dharma and Mimamsa

[edit]Mimamsa, developed through commentaries on its foundational texts, particularly the Mimamsa Sutras attributed to Jaimini, emphasizes "the desire to know dharma" as the central concern, defining dharma as what connects a person with the highest good, always yet to be realized. While some schools associate dharma with post-mortem existence, Mimamsakas focus on the continual renewal and realization of a ritual world through adherence to Vedic injunctions. They assert that the ultimate good is essentially inaccessible to perception and can only be understood through language, reflecting confidence in Vedic injunctions and the reality of language as a means of knowing.[55]

Mimamsa addresses the delayed results of actions (like wealth or heaven) through the concept of apurva or adrsta, an unseen force that preserves the connection between actions and their outcomes. This ensures that Vedic sacrifices, though their results are delayed, are effective and reliable in guiding toward dharma.[56]

In the Epics

[edit]The Hindu religion and philosophy, claims Daniel Ingalls, places major emphasis on individual practical morality. In the Sanskrit epics, this concern is omnipresent.[57] In Hindu Epics, the good, morally upright, law-abiding king is referred to as "dharmaraja".[58]

Dharma is at the centre of all major events in the life of Dasharatha, Rama, Sita, and Lakshman in Ramayana. In the Ramayana, Dasharatha upholds his dharma by honoring a promise to Kaikeyi, resulting in his beloved son Rama's exile, even though it brings him immense personal suffering.[59]

In the Mahabharata, dharma is central, and it is presented through symbolism and metaphors. Near the end of the epic, Yama referred to as dharma in the text, is portrayed as taking the form of a dog to test the compassion of Yudhishthira, who is told he may not enter paradise with such an animal. Yudhishthira refuses to abandon his companion, for which he is then praised by dharma.[60] The value and appeal of the Mahabharata, according to Ingalls, is not as much in its complex and rushed presentation of metaphysics in the 12th book.[59] Indian metaphysics, he argues, is more eloquently presented in other Sanskrit scriptures. Instead, the appeal of Mahabharata, like Ramayana, lies in its presentation of a series of moral problems and life situations, where there are usually three answers:[59] one answer is of Bhima, which represents brute force, an individual angle representing materialism, egoism, and self; the second answer is of Yudhishthira, which appeals to piety, deities, social virtue, and tradition; the third answer is of introspective Arjuna, which falls between the two extremes, and who, claims Ingalls, symbolically reveals the finest moral qualities of man. The Epics of Hinduism are a symbolic treatise about life, virtues, customs, morals, ethics, law, and other aspects of dharma.[61] There is extensive discussion of dharma at the individual level in the Epics of Hinduism; for example, on free will versus destiny, when and why human beings believe in either, the strong and prosperous naturally uphold free will, while those facing grief or frustration naturally lean towards destiny.[62] The Epics of Hinduism illustrate various aspects of dharma with metaphors.[63]

According to 4th-century Vatsyayana

[edit]According to Klaus Klostermaier, 4th-century CE Hindu scholar Vātsyāyana explained dharma by contrasting it with adharma.[64] Vātsyāyana suggested that dharma is not merely in one's actions, but also in words one speaks or writes, and in thought. According to Vātsyāyana:[64][65]

- Adharma of body: hinsa (violence), steya (steal, theft), pratisiddha maithuna (sexual indulgence with someone other than one's partner)

- Dharma of body: dana (charity), paritrana (succor of the distressed) and paricarana (rendering service to others)

- Adharma from words one speaks or writes: mithya (falsehood), parusa (caustic talk), sucana (calumny) and asambaddha (absurd talk)

- Dharma from words one speaks or writes: satya (truth and facts), hitavacana (talking with good intention), priyavacana (gentle, kind talk), svadhyaya (self-study)

- Adharma of mind: paradroha (ill will to anyone), paradravyabhipsa (covetousness), nastikya (denial of the existence of morals and religiosity)

- Dharma of mind: daya (compassion), asprha (disinterestedness), and sraddha (faith in others)

According to Patanjali Yoga

[edit]In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali the dharma is real; in the Vedanta it is unreal.[66]

Dharma is part of yoga, suggests Patanjali; the elements of Hindu dharma are the attributes, qualities and aspects of yoga.[66] Patanjali explained dharma in two categories: yamas (restraints) and niyamas (observances).[64]

The five yamas, according to Patanjali, are: abstain from injury to all living creatures, abstain from falsehood (satya), abstain from unauthorised appropriation of things-of-value from another (acastrapurvaka), abstain from coveting or sexually cheating on your partner, and abstain from expecting or accepting gifts from others.[67] The five yama apply in action, speech and mind. In explaining yama, Patanjali clarifies that certain professions and situations may require qualification in conduct. For example, a fisherman must injure a fish, but he must attempt to do this with least trauma to fish and the fisherman must try to injure no other creature as he fishes.[68]

The five niyamas (observances) are cleanliness by eating pure food and removing impure thoughts (such as arrogance or jealousy or pride), contentment in one's means, meditation and silent reflection regardless of circumstances one faces, study and pursuit of historic knowledge, and devotion of all actions to the Supreme Teacher to achieve perfection of concentration.[69]

Sources

[edit]Dharma is an empirical and experiential inquiry for every man and woman, according to some texts of Hinduism.[37][70] For example, Apastamba Dharmasutra states:

Dharma and Adharma do not go around saying, "That is us." Neither do gods, nor gandharvas, nor ancestors declare what is Dharma and what is Adharma.

— Apastamba Dharmasutra[71]

In other texts, three sources and means to discover dharma in Hinduism are described. These, according to Paul Hacker, are:[72] First, learning historical knowledge such as Vedas, Upanishads, the Epics and other Sanskrit literature with the help of one's teacher. Second, observing the behaviour and example of good people. The third source applies when neither one's education nor example exemplary conduct is known. In this case, "atmatusti" is the source of dharma in Hinduism, that is the good person reflects and follows what satisfies his heart, his own inner feeling, what he feels driven to.[72]

Dharma, life stages and social stratification

[edit]Some texts of Hinduism outline dharma for society and at the individual level. Of these, the most cited one is Manusmriti, which describes the four Varnas, their rights and duties.[73] Most texts of Hinduism, however, discuss dharma with no mention of Varna (caste).[74] Other dharma texts and Smritis differ from Manusmriti on the nature and structure of Varnas.[73] Yet, other texts question the very existence of varna. Bhrigu, in the Epics, for example, presents the theory that dharma does not require any varnas.[75] In practice, medieval India is widely believed to be a socially stratified society, with each social strata inheriting a profession and being endogamous. Varna was not absolute in Hindu dharma; individuals had the right to renounce and leave their Varna, as well as their asramas of life, in search of moksa.[73][76] While neither Manusmriti nor succeeding Smritis of Hinduism ever use the word varnadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas), or varnasramadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas and asramas), the scholarly commentary on Manusmriti use these words, and thus associate dharma with varna system of India.[73][77] In 6th-century India, even Buddhist kings called themselves "protectors of varnasramadharma" – that is, dharma of varna and asramas of life.[73][78]

At the individual level, some texts of Hinduism outline four āśramas, or stages of life as individual's dharma. These are:[79] (1) brahmacārya, the life of preparation as a student, (2) gṛhastha, the life of the householder with family and other social roles, (3) vānprastha or aranyaka, the life of the forest-dweller, transitioning from worldly occupations to reflection and renunciation, and (4) sannyāsa, the life of giving away all property, becoming a recluse and devotion to moksa, spiritual matters. Patrick Olivelle suggests that "ashramas represented life choices rather than sequential steps in the life of a single individual" and the vanaprastha stage was added before renunciation over time, thus forming life stages.[80]

The four stages of life complete the four human strivings in life, according to Hinduism.[81] Dharma enables the individual to satisfy the striving for stability and order, a life that is lawful and harmonious, the striving to do the right thing, be good, be virtuous, earn religious merit, be helpful to others, interact successfully with society. The other three strivings are Artha – the striving for means of life such as food, shelter, power, security, material wealth, and so forth; Kama – the striving for sex, desire, pleasure, love, emotional fulfilment, and so forth; and Moksa – the striving for spiritual meaning, liberation from life-rebirth cycle, self-realisation in this life, and so forth. The four stages are neither independent nor exclusionary in Hindu dharma.[81]

Dharma and poverty

[edit]According to Adam Bowles,[82] Shatapatha Brahmana verse 11.1.6.24 links social prosperity and dharma through water. It claims that waters come from rains; when rains are abundant, there is prosperity on the earth, and this prosperity enables people to follow Dharma – moral and lawful life. In times of distress, of drought, of poverty, everything suffers, including relations between human beings and the human ability to live according to dharma.[82]

In Rajadharmaparvan 91.34-8, the relationship between poverty and dharma reaches a full circle. A land with less moral and lawful life suffers distress, and as distress rises it causes more immoral and unlawful life, which further increases distress.[82][83] Those in power must follow the raja dharma (that is, dharma of rulers), because this enables the society and the individual to follow dharma and achieve prosperity.[84]

Dharma and law

[edit]The notion of dharma as duty or propriety is found in India's ancient legal and religious texts. Common examples of such use are pitri dharma (meaning a person's duty as a father), putra dharma (a person's duty as a son), raj dharma (a person's duty as a king) and so forth.[28] In Hindu philosophy, justice, social harmony, and happiness requires that people live per dharma. The Dharmashastra is a record of these guidelines and rules.[85] The available evidence suggest India once had a large collection of dharma related literature (sutras, shastras); four of the sutras survive and these are now referred to as Dharmasutras.[71] Along with laws of Manu in Dharmasutras, exist parallel and different compendium of laws, such as the laws of Narada and other ancient scholars.[86][87] These different and conflicting law books are neither exclusive, nor do they supersede other sources of dharma in Hinduism. These Dharmasutras include instructions on education of the young, their rites of passage, customs, religious rites and rituals, marital rights and obligations, death and ancestral rites, laws and administration of justice, crimes, punishments, rules and types of evidence, duties of a king, as well as morality.[71]

Buddhism

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Buddhism held the Hindu view of Dharma as "cosmic law", as in the working of Karma.[1] The term Dharma (Pali: dhamma) later came to refer to the teachings of the Buddha (pariyatti); the practice (paṭipatti) of the Buddha's teachings is then comprehended as Dharma.[1][88] In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for "phenomena".[88][2]

Buddha's teachings

[edit]For practising Buddhists, references to dharma (dhamma in Pali) particularly as "the dharma", generally means the teachings of the Buddha, commonly known throughout the East as Buddhadharma. It includes especially the discourses on the fundamental principles (such as the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path), as opposed to the parables and to the poems. The Buddha's teachings explain that in order to end suffering, dharma, or the right thoughts, understanding, actions and livelihood, should be cultivated.[89]

The status of dharma is regarded variably by different Buddhist traditions. Some regard it as an ultimate truth, or as the fount of all things which lie beyond the "three realms" (Sanskrit: tridhatu) and the "wheel of becoming" (Sanskrit: bhavachakra). Others, who regard the Buddha as simply an enlightened human being, see the dharma as the essence of the "84,000 different aspects of the teaching" (Tibetan: chos-sgo brgyad-khri bzhi strong) that the Buddha gave to various types of people, based upon their individual propensities and capabilities.

Dharma refers not only to the sayings of the Buddha, but also to the later traditions of interpretation and addition that the various schools of Buddhism have developed to help explain and to expound upon the Buddha's teachings. For others still, they see the dharma as referring to the "truth", or the ultimate reality of "the way that things really are" (Tibetan: Chö).

The dharma is one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism in which practitioners of Buddhism seek refuge, or that upon which one relies for his or her lasting happiness. The Three Jewels of Buddhism are the Buddha, meaning the mind's perfection of enlightenment, the dharma, meaning the teachings and the methods of the Buddha, and the Sangha, meaning the community of practitioners who provide one another guidance and support.

Chan Buddhism

[edit]Dharma is employed in Chan Buddhism in a specific context in relation to transmission of authentic doctrine, understanding and bodhi; recognised in dharma transmission.

Theravada Buddhism

[edit]In Theravada Buddhism obtaining ultimate realisation of the dhamma is achieved in three phases; learning, practising and realising.[90]

In Pali:

Jainism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

The word dharma in Jainism is found in all its key texts. It has a contextual meaning and refers to a number of ideas. In the broadest sense, it means the teachings of the Jinas,[1] or teachings of any competing spiritual school,[91] a supreme path,[92] socio-religious duty,[93] and that which is the highest mangala (holy).[94]

The Tattvartha Sutra, a major Jain text, mentions daśa dharma (lit. 'ten dharmas') with referring to ten righteous virtues: forbearance, modesty, straightforwardness, purity, truthfulness, self-restraint, austerity, renunciation, non-attachment, and celibacy.[95] Ācārya Amṛtacandra, author of the Jain text, Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya writes:[96]

A right believer should constantly meditate on virtues of dharma, like supreme modesty, in order to protect the Self from all contrary dispositions. He should also cover up the shortcomings of others.

— Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya (27)

Dharmāstikāya

[edit]The term dharmāstikāya (Sanskrit: धर्मास्तिकाय) also has a specific ontological and soteriological meaning in Jainism, as a part of its theory of six dravya (substance or a reality). In the Jain tradition, existence consists of jīva (soul, ātman) and ajīva (non-soul, anātman), the latter consisting of five categories: inert non-sentient atomic matter (pudgalāstikāya), space (ākāśa), time (kāla), principle of motion (dharmāstikāya), and principle of rest (adharmāstikāya).[97][98] The use of the term dharmāstikāya to mean motion and to refer to an ontological sub-category is peculiar to Jainism, and not found in the metaphysics of Buddhism and various schools of Hinduism.[98]

Sikhism

[edit]

For Sikhs, the word dharam (Punjabi: ਧਰਮ, romanized: dharam) means the path of righteousness and proper religious practice.[99] Guru Granth Sahib connotes dharma as duty and moral values.[100] The 3HO movement in Western culture, which has incorporated certain Sikh beliefs, defines Sikh Dharma broadly as all that constitutes religion, moral duty and way of life.[101]

In Sangam literature

[edit]Several works of the Sangam and post-Sangam period, many of which are of Hindu or Jain origin, emphasizes on dharma. Most of these texts are based on aṟam, the Tamil term for dharma. The ancient Tamil moral text of the Tirukkuṟaḷ or Kural, a text probably of Jain or Hindu origin,[102][103][104][105][106] despite being a collection of aphoristic teachings on dharma (aram), artha (porul), and kama (inpam),[107][108] is completely and exclusively based on aṟam.[109] The Naladiyar, a Jain text of the post-Sangam period, follows a similar pattern as that of the Kural in emphasizing aṟam or dharma.[110]

Dharma in symbols

[edit]

The importance of dharma to Indian civilization is illustrated by India's decision in 1947 to include the Ashoka Chakra, a depiction of the dharmachakra (the "wheel of dharma"), as the central motif on its flag.[111]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c From the Oxford Dictionary of World Religions: "In Hinduism, dharma is a fundamental concept, referring to the order and custom which make life and a universe possible, and thus to the behaviours appropriate to the maintenance of that order."[1]

- ^ David Kalupahana: "The old Indian term dharma was retained by the Buddha to refer to phenomena or things. However, he was always careful to define this dharma as "dependently arisen phenomena" (paticca-samuppanna-dhamma) ... In order to distinguish this notion of dhamma from the Indian conception where the term dharma meant reality (atman), in an ontological sense, the Buddha utilised the conception of result or consequence or fruit (attha, Sk. artha) to bring out the pragmatic meaning of dhamma."[2]

- ^ The common duties of Sadharana-dharma is based on the idea that, individuals (Jiva) are born with a number of debts, hence through common moral duties prescribed in the Sadharana dharma would help to repay one's debts to the humanity.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Bowker, John (June 8, 2018). "Dharma". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b Kalupahana, David (1986) The Philosophy of the Middle Way. SUNY Press, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Barnhart, R. K. (ed.) (1998) Chambers Dictionary of Etymology.

- ^ Day 1982, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Brereton 2004.

- ^ "How did the 'Ramayana' and 'Mahabharata' come to be (and what has 'dharma' got to do with it)?". 13 December 2018.

- ^ Hiltebeitel 2011, pp. 36–37.

- ^ see below:

- Van Buitenen (1957);

- Fitzgerald, James (2004), "Dharma and its Translation in the Mahābhārata", Journal of Indian philosophy, 32(5), pp. 671–685; Quote – "virtues enter the general topic of dharma as 'common, or general, dharma', ..."

- ^ see:

- Frawley, David (2009), Yoga and Ayurveda: Self-Healing and Self-Realization, ISBN 978-0-9149-5581-8; Quote – "Yoga is a dharmic approach to the spiritual life...";

- Harvey, Mark (1986), The Secular as Sacred?, Modern Asian Studies, 20(2), pp. 321–331.

- ^ Jackson, Bernard S. (1975), "From dharma to law", The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Summer, 1975), pp. 490–512.

- ^ Flood 1994, "Chapter 3"; Quote – "Rites of passage are dharma in action."; "Rites of passage, a category of rituals,..."

- ^ Coward 2004; Quote – "Hindu stages of life approach (ashrama dharma)..."

- ^ see:

- Creel, Austin (1975), "The Reexamination of Dharma in Hindu Ethics", Philosophy East and West, 25(2), pp. 161–173; Quote – "Dharma pointed to duty, and specified duties..";

- Trommsdorff, Gisela (2012), Development of "agentic" regulation in cultural context: the role of self and world views, Child Development Perspectives, 6(1), pp. 19–26; Quote – "Neglect of one's duties (dharma – sacred duties toward oneself, the family, the community, and humanity) is seen as an indicator of immaturity."

- ^ Dhand, Arti (17 December 2002). "The Dharma of Ethics, the Ethics of Dharma: Quizzing the Ideals of Hinduism". Journal of Religious Ethics. 30 (3): 351. doi:10.1111/1467-9795.00113. ISSN 1467-9795.

- ^ a b "dharma". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Van Buitenen 1957, p. 36.

- ^ See:

- ^ a b c d e f g h Horsch 2004.

- ^ Hermann Grassmann, Worterbuch zum Rig-veda (German Edition), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1636-7

- ^ a b c d e Rosen 2006, pp. 34–45.

- ^ see:

- "Dharma" Monier Monier-Williams, Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary (2008 revision), pp. 543–544;

- Carl Cappeller (1999), Monier-Williams: A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Etymological and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-81-206-0369-1, pp. 510–512.

- ^ Jacobs 2010, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d see:

- English translated version by Jarrod Whitaker: Horsch, Paul, (December 2004) "From Creation Myth to World Law: the Early History of Dharma", Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 32, Issue 5–6, pp. 423–448; Original peer-reviewed publication in German: Horsch, Paul, (1967) "Vom Schoepfungsmythos zum Weltgesetz", Asiatische Studien: Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Asiankunde, Volume 21, pp. 31–61;

- English translated version by Donald R. Davis: Paul Hacker, (2006) "Dharma in Hinduism", Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 34, Issue 5, pp. 479–496; Original peer-reviewed publication in German: Paul Hacker, (1965) "Dharma im Hinduismus" Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft und Religionswissenschaft Volume 49, pp. 93–106.

- ^ see:

- Bowker (2018); "...the order and custom which make life and a universe possible, and thus to the behaviours appropriate to the maintenance of that order".

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, 2007.[full citation needed]

- ^ see:

- Albrecht Wezler, "Dharma in the Veda and the Dharmaśāstras", Journal of Indian Philosophy, December 2004, Volume 32, Issue 5–6, pp. 629–654

- Johannes Heesterman (1978). "Veda and Dharma", in W. D. O'Flaherty (ed.), The Concept of Duty in South Asia, New Delhi: Vikas, ISBN 978-0-7286-0032-4, pp. 80–95

- K. L. Seshagiri Rao (1997), "Practitioners of Hindu Law: Ancient and Modern", Fordham Law Review, Volume 66, pp. 1185–1199.

- ^ Jacobs 2010, p. 58.

- ^ a b Kumar & Choudhury 2021.

- ^ see

- ^ see:

- Flood (1998), pp. 30–54 and 151–152;

- Coward (2004);

- Van Buitenen (1957), p. 37.

- ^ RgVeda 6.70.1, 8.41.10, 10.44.8, for secondary source see Karl Friedrich Geldner, Der Rigveda in Auswahl (2 vols.), Stuttgart; and Harvard Oriental Series, 33–36, Bd. 1–3: 1951.

- ^ Horsch 2004, pp. 430–431.

- ^ Horsch 2004, pp. 430–432.

- ^ P. Thieme, Gedichte aus dem Rig-Veda, Reclam Universal-Bibliothek Nr. 8930, p. 52.

- ^ a b Brereton (2004); "There are Indo-European parallels to dhárman (cf. Wennerberg 1981: 95f.), but the only Iranian equivalent is Old Persian darmān, 'remedy', which has little bearing on Indo-Aryan dhárman. There is thus no evidence that IIr. *dharman was a significant culture word during the Indo-Iranian period." (p. 449) "The origin of the concept of dharman rests in its formation. It is a Vedic, rather than an Indo-Iranian word, and a more recent coinage than many other key religious terms of the Vedic tradition. Its meaning derives directly from dhr 'support, uphold, give foundation to' and therefore 'foundation' is a reasonable gloss in most of its attestations." (p. 485).

- ^ Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2011). The Religion Toolkit: A Complete Guide to Religious Studies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 324. ISBN 978-1-4443-4371-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Hacker 2006.

- ^ Etienne Lamotte, Bibliothèque du Museon 43, Louvain, 1958, p. 249.

- ^ a b Koller 1972, pp. 136–142.

- ^ Holdrege, Barbara (2004), "Dharma" in: Mittal & Thursby (eds.) The Hindu World, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21527-7, pp. 213–248.

- ^ "Māyā" Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, ISBN 978-81-206-0369-1

- ^ Northrop, F. S. C. (1949), "Naturalistic and cultural foundations for a more effective international law", Yale Law Journal, 59, pp. 1430–1441.

- ^ Day 1982, pp. 42–44.

- ^ "Dharma", The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (2013), Columbia University Press, Gale, ISBN 978-0-7876-5015-5

- ^ a b Van Buitenen 1957.

- ^ see:

- "Dharma", The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (2013), Columbia University Press, Gale, ISBN 978-0-7876-5015-5;

- Rosen (2006), "Chapter 3".

- ^ "Sanatana dharma". Encyclopædia Britannica, 18 Jun. 2009. Accessed 14 September 2021.

- ^ Conlon 1994, p. 50.

- ^ Fritzman 2015, p. 326.

- ^ a b Grimes 1996, p. 112.

- ^ Kumar & Choudhury 2021, p. 8.

- ^ Grimes 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Grimes 1996, p. 112-113.

- ^ a b Johnston, Charles, The Mukhya Upanishads: Books of Hidden Wisdom, Kshetra, ISBN 978-1-4959-4653-0, p. 481, for discussion: pp. 478–505.

- ^ Arnold, Daniel (Summer 2024), "Kumārila", in Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, archived from the original on 8 Jul 2024, retrieved 2024-04-11

- ^ Junankar, N. S. (1982). "The Mīmāṃsā Concept of Dharma". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 10 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1007/BF00200183. ISSN 0022-1791. JSTOR 23444178.

- ^ Ingalls 1957, p. 43.

- ^ Fitzgerald, James L. (2004) The Mahābhārata: Vol. 7, Book 11: The Book of Women; Book 12: The Book of Peace, Part 1. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226252506. p. 124. OCLC 59170383

- ^ a b c Ingalls 1957, pp. 41–48.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 17: Mahaprasthanika Parva: Section 3". Archived from the original on Jan 13, 2024 – via Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ There is considerable amount of literature on dharma-related discussion in Hindu Epics: of Egoism versus Altruism, Individualism versus Social Virtues and Tradition; for examples, see:

- Meyer, Johann Jakob (1989), Sexual life in ancient India, ISBN 81-208-0638-7, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 92–93; Quote – "In Indian literature, especially in Mahabharata over and over again is heard the energetic cry – Each is alone. None belongs to anyone else, we are all but strangers to strangers; (...), none knows the other, the self belongs only to self. Man is born alone, alone he lives, alone he dies, alone he tastes the fruit of his deeds and his ways, it is only his work that bears him company. (...) Our body and spiritual organism is ever changing; what belongs, then, to us? (...) Thus, too, there is really no teacher or leader for anyone, each is his own Guru, and must go along the road to happiness alone. Only the self is the friend of man, only the self is the foe of man; from others nothing comes to him. Therefore, what must be done is to honor, to assert one's self..."; Quote – "(in parts of the epic), the most thoroughgoing egoism and individualism is stressed..."

- Piper, Raymond F. (1954), "In Support of Altruism in Hinduism", Journal of Bible and Religion, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jul., 1954), pp. 178–183

- Ganeri, J. (2010), A Return to the Self: Indians and Greeks on Life as Art and Philosophical Therapy, Royal Institute of Philosophy supplement, 85(66), pp. 119–135.

- ^ Ingalls (1957), pp. 44–45; Quote – "(...)In the Epic, free will has the upper hand. Only when a man's effort is frustrated or when he is overcome with grief does he become a predestinarian (believer in destiny)."; Quote – "This association of success with the doctrine of free will or human effort (purusakara) was felt so clearly that among the ways of bringing about a king's downfall is given the following simple advice: 'Belittle free will to him, and emphasise destiny.'" (Mahabharata 12.106.20).

- ^ Smith, Huston (2009) The World Religions, HarperOne, ISBN 978-0-06-166018-4; For summary notes: Background to Hindu Literature Archived 2004-09-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Klostermaier, Klaus. Chapter 3: "Hindu dharma", A survey of Hinduism, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-88706-807-3.

- ^ Gautama's Nyāyasūtras, with Vātsyāyana-Bhāṣya. 2 vols. Translated by Ganganatha Jha. Oriental Books. 1939.

- ^ a b Woods 1914, p. [page needed].

- ^ Woods 1914, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Woods 1914, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Woods 1914, pp. 181–191.

- ^ Kumarila Bhatta, Tantravarttika, Anandasramasamskrtagranthavalih, Vol. 97, pp. 204–205. (in Sanskrit); For an English Translation, see Ganganatha Jha (tr.) (1924), Bibliotheca Indica, Work No. 161, Vol. 1.

- ^ a b c Olivelle 1999, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Hacker 2006, pp. 487–489.

- ^ a b c d e Hiltebeitel 2011, pp. 215–227.

- ^ Thapar, R. (1995), The first millennium BC in northern India, Recent perspectives of early Indian history, 80–141.

- ^ Trautmann, Thomas R. (Jul 1964), "On the Translation of the Term Varna", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 7(2) pp. 196–201.

- ^ see:

- Van Buitenen (1957), pp. 38–39.

- Koller (1972), pp. 131–144.

- ^ Kane, P.V. (1962), History of Dharmasastra (Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law in India), Volume 1, pp. 2–10.

- ^ Olivelle, P. (1993). The Asrama System: The history and hermeneutics of a religious institution, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Widgery 1930.

- ^ Glucklich, Ariel (2008). The strides of Vishnu: Hindu culture in historical perspective. Oxford: Oxford University press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-19-531405-2.

- ^ a b see:

- Koller (1972), pp. 131–144.

- Potter (1958), pp. 49–63.

- Goodwin (1955), pp. 321–344.

- ^ a b c Bowles, Adam (2007), "Chapter 3", Dharma, Disorder, and the Political in Ancient India, Brill's Indological Library (Book 28), ISBN 978-90-04-15815-3.

- ^ Derrett, J. D. M. (1959), "Bhu-bharana, bhu-palana, bhu-bhojana: an Indian conundrum", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 22, pp. 108–123.

- ^ Gonda, Jan, "Ancient Indian Kingship from the Religious Point of View", Numen, Vol. 3, Issue 1 (Jan., 1956), pp. 36–71.

- ^ Gächter, Othmar (1998). "Anthropos". Anthropos Institute.

- ^ Davis, Donald Jr. (September 2006) "A Realist View of Hindu Law", Ratio Juris. Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 287–313.

- ^ Lariviere, Richard W. (2003), The Naradasmrti, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- ^ a b "dhamma", The New Concise Pali English Dictionary.

- ^ Brown, Hannah Jean (2019). "Key Tenets of Classical Buddhist Dharma Leave Space for the Practice of Abortion and are Upheld by Contemporary Japanese Buddhist Mizuko Kuyo Remembrance Rituals". Journal of Religion and Health. 58 (2): 477. doi:10.1007/s10943-019-00763-4. PMID 30673995.

- ^ a b Lee Dhammadharo, Ajaan (1994). "What is the Triple Gem? – Dhamma: Good Dhamma is of three sorts". Translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. p. 33.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 100.

- ^ Clarke, Peter B.; Beyer, Peter (2009). The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. Taylor & Francis. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-135-21100-4.

- ^ Brekke, Torkel (2002). Makers of Modern Indian Religion in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-19-925236-7.

- ^ Cort 2001, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 128.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Cort, John E. (1998). Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History. State University of New York Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-7914-3786-5.

- ^ a b Paul Dundas (2003). The Jains (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5.

- ^ Rinehart, Robin (2014), in Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies, ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8, Oxford University Press, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Cole, W. Owen (2014), in Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies, ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8, Oxford University Press, p. 254.

- ^ Dusenbery, Verne (2014), in Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies, ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8, Oxford University Press, pp. 560–568.

- ^ Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 156–171. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

- ^ Lal, Mohan (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 4333–4334, 4341–4342. ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2012). Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–154. ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8.

- ^ Iraianban, Swamiji (1997). Ambrosia of Thirukkural. Abhinav Publications. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-7017-346-5.

- ^ Purnalingam Pillai 2015, p. 75.

- ^ Blackburn, Stuart (April 2000). "Corruption and Redemption: The Legend of Valluvar and Tamil Literary History". Modern Asian Studies. 34 (2). Cambridge University Press: 453. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00003632. S2CID 144101632.

- ^ Sanjeevi, N. (2006). First All India Tirukkural Seminar Papers (2nd ed.). Chennai: University of Madras. p. 82.

- ^ Velusamy, N.; Faraday, Moses Michael, eds. (2017). Why Should Thirukkural Be Declared the National Book of India? (in Tamil and English) (1st ed.). Chennai: Unique Media Integrators. p. 55. ISBN 978-93-85471-70-4.

- ^ Purnalingam Pillai 2015, p. 70.

- ^ Narula, S. (2006), International Journal of Constitutional Law, 4(4), pp. 741–751.

Sources

[edit]- Brereton, Joel P. (December 2004). "Dhárman In The Rgveda". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 32 (5–6): 449–489. doi:10.1007/s10781-004-8631-8. ISSN 0022-1791. S2CID 170807380.

- Conlon, Frank F. (1994). "Hindu revival and Indian womanhood: The image and status of women in the writings of Vishnubawa Brahamachari". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 17 (2): 43–61. doi:10.1080/00856409408723205.

- Cort, John E. (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9.

- Coward, Harold (2004). "Hindu bioethics for the twenty-first century". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 291 (22): 2759–2760. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2759.

- Day, Terence P. (1982). The Conception of Punishment in Early Indian Literature. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-919812-15-4.

- Flood, Gavin (1994). "Hinduism". In Jean Holm; John Bowker (eds.). Rites of Passages. A&C Black. ISBN 1-85567-102-6.

- Flood, Gavin (1998). "Chapter 2, Making moral decisions". In Paul Bowen (ed.). Themes and issues in Hinduism. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-33851-1.

- Fritzman, J.M. (2015). "The Bhagavadgītā, Sen, and Anderson". International Journal of the Philosophical Traditions of the East. 25 (4): 319–338. doi:10.1080/09552367.2015.1102693. S2CID 146705129.

- Goodwin, William F. (Jan 1955). "Ethics and Value in Indian Philosophy". Philosophy East and West. 4 (4): 321–344. doi:10.2307/1396742. JSTOR 1396742.

- Grimes, John A. (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791430677.

- Hacker, Paul (October 2006). "Dharma in Hinduism". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 34 (5). Translated by Donald R. Davis: 479–496. doi:10.1007/s10781-006-9002-4. JSTOR 23497312.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2011). Dharma: Its Early History in Law, Religion, and Narrative. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-539423-8.

- Horsch, Paul (December 2004). "From Creation Myth to World Law: the Early History of Dharma". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 32 (5–6). Translated by Jarrod Whitaker: 423–448. doi:10.1007/s10781-004-8628-3. JSTOR 23497148.

- Ingalls, Daniel H. H. (Apr–Jul 1957). "Dharma and Moksa". Philosophy East and West. 7 (1/2): 41–48. doi:10.2307/1396833. JSTOR 1396833.

- Jacobs, Stephen (2010). Hinduism Today. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826440273.

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011). Acharya Umasvami's Tattvārthsūtra. Vikalp Printers. ISBN 978-81-903639-2-1.

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012). Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya. Vikalp Printers. ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5.

- Koller, J. M. (1972). "Dharma: an expression of universal order". Philosophy East and West. 22 (2): 131–144. doi:10.2307/1398120. JSTOR 1398120.

- Kumar, Shailendra; Choudhury, Sanghamitra (2021) [Published online: 27 Dec 2020]. Meissner, Richard (ed.). "Ancient Vedic Literature and Human Rights: Resonances and Dissonances". Cogent Social Sciences. 7 (1). 1858562. doi:10.1080/23311886.2020.1858562. ISSN 2331-1886. S2CID 234164343.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1999). Dharmasūtras: The Law Codes of Ancient India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283882-2.

- Potter, Karl H. (Apr–Jul 1958). "Dharma and Mokṣa from a Conversational Point of View". Philosophy East and West. 8 (1/2): 49–63. doi:10.2307/1397421. JSTOR 1397421.

- Purnalingam Pillai, M. S. (2015). Tamil Literature. Chennai: International Institute of Tamil Studies.

- Rocher, Ludo (2003). "Chapter 4, The Dharmasastra". In Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-21535-6.

- Rosen, Steven (2006). Essential Hinduism. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-99006-0.

- Van Buitenen, J. A. B. (Apr–Jul 1957). "Dharma and Moksa". Philosophy East and West. 7 (1/2): 33–40. doi:10.2307/1396832. JSTOR 1396832.

- Widgery, Alban G. (Jan 1930). "The Principles of Hindu Ethics". International Journal of Ethics. 40 (2): 232–245. doi:10.1086/intejethi.40.2.2377977.

- Woods, James Haughton (1914). The yoga-system of Patanjali. Harvard University Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Sanatana Dharma: an advanced text book of Hindu religion and Ethics. Central Hindu College, Benaras. 1904.

- Dasgupta, Surendranath (1955) [1949]. A History of Indian Philosophy: Indian Pluralism. Vol. IV. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–11.

- Murthy, K. Krishna. "Dharma – Its Etymology." The Tibet Journal, Vol. XXI, No. 1, Spring 1966, pp. 84–87.

- Olivelle, Patrick (2009). Dharma: Studies in Its Semantic, Cultural and Religious History. Delhi: MLBD. ISBN 978-81-208-3338-8.

External links

[edit]- India Glossary – Dharma (archived 28 February 2010)

- Buddhism A–Z: "D" Entries Archived 2012-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Rajiv Malhotra, Dharma Is Not The Same As Religion (huffingtonpost.com)

Dharma

View on GrokipediaDharma (Sanskrit: धर्म; Pali: धम्म) is a central concept in the Indic traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, denoting the underlying order of the cosmos, the duties that sustain social and natural harmony, and the moral principles guiding individual conduct toward righteousness and liberation. Derived from the Sanskrit verbal root dhṛ ("to uphold" or "to support"), the term originally signified the eternal laws (dharmāṇi sanatā) that maintain universal stability, as reflected in the Rigveda where it aligns with ṛta, the principle of cosmic truth and regularity.[1][2] In Hinduism, dharma manifests as svadharma—personal duties tied to one's social class (varṇa) and life stage (āśrama)—prescribing ethical actions to preserve societal order and fulfill karmic obligations.[3] Buddhism reinterprets it as dhamma, the Buddha's teachings encapsulating the natural law of impermanence, suffering, and non-self, serving as the path to enlightenment.[1] In Jainism, dharma emphasizes non-violence (ahiṃsā) and ethical discipline as the means to purify the soul and escape the cycle of rebirth, while in Sikhism, it underscores righteous living, honest labor, and devotion to the divine will.[4][5] These traditions share dharma's causal role in upholding reality through adherence to truth-derived duties, though interpretations vary, with no single universal doctrine dominating across them.[2]

Etymological and Conceptual Foundations

Etymology

The term dharma derives from the Sanskrit root dhṛ ("to hold," "to support," or "to uphold"), traceable to the Proto-Indo-European root dʰer- ("to hold firmly, support"), which conveys foundational stability and maintenance.[6] This root yields cognates such as Latin firmus ("firm, stable," from dʰer-mo-) and Greek thrónos ("throne," implying a supported seat of power).[7] In Sanskrit, the nominal form dhárman- (neuter) or dharmán- (masculine) emerges as a thematic derivative, denoting that which upholds or establishes order. Earliest attestations of dharma occur in the Rigveda, composed around 1500–1200 BCE, where it signifies the sustaining forces or eternal laws (dharmāṇi sanā́tāni) that maintain cosmic harmony, paralleling ṛta as the intrinsic order of truth and regularity in the universe. In this context, dharma often describes ritual acts or divine ordinances that reinforce the stability of natural and sacrificial processes against chaos.[8] During the middle and late Vedic periods (circa 1200–500 BCE), dharma's semantics evolve from primary emphases on ritual sustenance and cosmic fixtures to broader connotations of normative decree, moral propriety, and obligatory conduct, as seen in texts like the Brāhmaṇas and early Upaniṣads.[9] This shift marks dharma as a principle bridging impersonal order with human agency in upholding societal and ethical structures.[10]Core Definitions and Polysemy

Dharma denotes the foundational principle of upholding or sustaining the inherent order of existence, serving as the cosmic law that preserves the stability of natural and universal structures.[11] This sense emphasizes dharma's role in maintaining reality's coherence, where deviations disrupt causal sequences leading to disorder.[8] Righteousness constitutes another core dimension, defined as deliberate conformity to this order through actions that align individual conduct with observable natural patterns, thereby averting entropy in moral and physical domains.[12] Duty represents the practical application, encompassing obligations tailored to sustain equilibrium within specific relational contexts, functioning as behavioral rules that enforce reciprocity and prevent systemic breakdown.[13] The concept's polysemy arises from its dual operation across universal and particular registers, enabling adaptive yet principled responses to varying scales of order. Universal dharma, often termed sanatana dharma, articulates timeless axioms governing all entities, independent of temporal or situational variance, as the immutable framework underpinning cosmic and ethical invariance. Particular dharma, or svadharma, contextualizes these universals into individualized mandates, derived from positional factors like role or circumstance, ensuring that localized duties reinforce rather than contradict the broader causal architecture.[14] This layered structure mitigates conflicts between general principles and specific exigencies, prioritizing alignment with sustaining forces over rigid uniformity. Causally, dharma operates as a regulatory mechanism fostering social cohesion and personal efficacy by linking adherence to outcomes of harmony and prosperity, with non-conformance yielding discord and decline.[15] Empirical indicators include the protracted endurance of Indic civilizational frameworks, which have withstood successive invasions and transformations while retaining ethical continuities traceable to at least 1500 BCE, attributable in part to dharma's embedded incentives for mutual obligation and adaptive governance.[16][17] This resilience underscores dharma's function not as abstract ideal but as a verifiable contributor to long-term societal viability, where collective fidelity to order-preserving norms correlates with reduced internal fragmentation.Historical Development

Pre-Vedic and Vedic Origins

The concept of dharma emerges in the earliest Vedic texts as a principle integral to upholding ṛta, the objective cosmic order governing natural cycles, seasonal rhythms, and ritual efficacy, with the Rigveda dated to circa 1500–1200 BCE based on linguistic and archaeological correlations.[18] In these hymns, dharma—derived from the verbal root dhṛ meaning "to uphold" or "sustain"—denotes the stable, supportive force that maintains ṛta against chaos, often manifested through precise sacrificial actions (yajña) that align human conduct with universal regularity.[19] This linkage positions dharma not as abstract morality but as causal mechanism ensuring the perpetuation of order, where deviations invite disorder (anṛta)./5_Anantasri.pdf) Textual evidence from the Rigveda records dharma approximately 56 times, frequently in contexts intertwining it with satyam (truth as foundational reality), portraying both as emergent from primordial austerity to regulate post-creational laws./5_Anantasri.pdf) For instance, cosmogonic passages describe ṛta and its sustaining dharma as arising after the initial undifferentiated state, imposing structure on phenomena like day-night alternation and moral reciprocity, thereby extending cosmic regularity to nascent social norms among Vedic communities.[20] This formulation underscores a realist ontology: dharma affirms verifiable, law-like invariance in reality, reliant on empirical observation of natural patterns rather than subjective whim. Pre-Vedic cosmological precursors to dharma lack direct attestation due to the oral-pre-literate nature of earlier traditions, but conceptual affinities appear in reconstructed proto-Indo-Iranian motifs of ordered creation, where ritual sustenance of harmony parallels Avestan aša (truth-order), suggesting continuity from migratory steppe cultures into the Indian subcontinent around 2000 BCE.[21] However, Vedic texts prioritize ṛta's self-evident governance over speculative anthropogeny, with dharma as ritual enactment countering disruptive forces. In contrast to māyā—depicted in Rigvedic hymns as the gods' dynamic, illusory crafting power (e.g., Indra's shape-shifting feats)—dharma embodies enduring stability, rejecting relativism by grounding human and divine agency in unyielding causal laws observable in ritual outcomes and ecological consistency.[8] This distinction establishes dharma's primacy in Vedic realism, where truth (satyam) and order (ṛta) demand conformity for coherence, prefiguring ethical imperatives without later metaphysical overlays.[19]Upanishadic and Brahmanical Expansions

In the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, composed circa 700 BCE, dharma evolves from Vedic ritual prescriptions to an internalized ethical and metaphysical principle embodying cosmic order and interdependence.[22] The text portrays dharma as the cohesive force binding disparate elements, where "this righteousness (dharma) is like honey to all beings, and all beings are like honey to this righteousness," highlighting mutual sustenance among phenomena.[23] This interdependence underscores dharma's role as a self-evident truth (satya), guiding conduct through observable effects rather than exclusive reliance on priestly rites, with its essence tied to the immortal Self (ātman) pervading all.[23] Dharma here functions as an inner directive for ethical alignment with universal reality, distinct from external sacrifices, as it consists of scriptural injunctions (śruti and smṛti), practiced virtues, and invisible potencies (apūrva) that manifest empirically in worldly stability, such as the earth's firmness.[23] This shift reflects causal realism: ethical adherence sustains harmony by integrating individual actions with broader reciprocity, fostering piety akin to ordered devotion grounded in the observed unity of existence over ritual mechanics alone.[24] Brahmanical expansions in the Dharma-sūtras, dating from approximately 600 BCE to 200 BCE, further systematize dharma by codifying varna-specific duties, linking abstract ethics to practical social functions for empirical stability.[25] Works like the Gautama Dharma-sūtra delineate obligations—Brahmins for teaching and rituals, Kshatriyas for protection, Vaiśyas for production, and Śūdras for service—positing these as reciprocal roles derived from qualities (guṇa) and actions (karma), which prevent disorder by specializing labor and upholding societal cohesion.[26] Such prescriptions aim at causal outcomes: adherence yields observed harmony in ancient communities, mirroring cosmic principles and averting fragmentation through structured interdependence.[27]Epic and Puranic Formulations

In the Indian epics, particularly the Mahabharata and Ramayana, dharma is dramatized through narratives of moral dilemmas known as dharma-samkata, where characters confront conflicting duties that underscore dharma's context-dependent application rather than rigid universals. These stories illustrate dharma as a pragmatic framework responsive to individual roles, social positions, and foreseeable consequences of actions, prioritizing causal outcomes over abstract ideals. For instance, in the Ramayana, Rama faces a dharma-samkata between personal affection for Sita and his rajadharma as king, ultimately prioritizing public welfare by adhering to societal expectations of royal conduct, even at personal cost.[28] Similarly, the Mahabharata abounds with such conflicts, as seen in Yudhishthira's adherence to truthfulness leading to unintended harms, revealing dharma's inherent tensions in real-world application.[29] Central to the Mahabharata's formulation is the Bhagavad Gita, embedded in its Bhishma Parva, where Krishna advises Arjuna amid his battlefield reluctance to fight kin. Krishna emphasizes svadharma—one's duty aligned with inherent qualities (svabhava) and social role—over performative adherence to others' duties, stating that imperfect fulfillment of one's own dharma surpasses perfect execution of another's.[30] [31] This counsel prioritizes action (karma) detached from ego-driven results, recognizing causal chains where inaction or misaligned duty disrupts cosmic and social order. Scholarly estimates date the Gita's composition between the 5th century BCE and 2nd century CE, reflecting its evolution within epic layers.[32] Such teachings highlight dharma's realism: duties vary by varna (e.g., a kshatriya's martial obligation) and circumstance, with ethical choices evaluated by long-term effects rather than immediate sentiment.[33] Puranic texts expand epic dharma by integrating it with bhakti (devotion), adapting it for broader accessibility beyond elite ritualism. In the Vishnu Purana, dharma is framed as upheld through loving surrender to Vishnu, where devotional acts fulfill duties while transcending karmic binds, making ethical conduct viable for masses via personal divine relation rather than scholastic mastery.[34] This synthesis renders dharma practical for varied practitioners, emphasizing bhakti's role in resolving dilemmas through divine guidance.[35] Epic and Puranic conceptions influenced governance, paralleling rajadharma in Kautilya's Arthashastra (circa 300 BCE), which mandates kings to protect subjects, administer justice, and prioritize collective welfare—mirroring epic kings like Rama or Yudhishthira whose duties extend to societal stability over personal gain.[36] [37] These texts evidence dharma's operationalization in statecraft, where rulers' adherence ensures order amid conflicting imperatives.[38]Dharma in Hinduism

Scriptural Sources in Vedas and Smritis

In the Vedic corpus, dharma emerges as a principle sustaining ṛta, the cosmic order governing natural and moral phenomena, with yajña (ritual sacrifice) serving as the primary mechanism for its maintenance. The Rigveda uses dhárman to signify supportive ordinances or laws that align human actions with this eternal rhythm, as seen in hymns invoking deities to enforce righteous conduct amid chaos.[8] The Yajurveda extends this by detailing procedural formulas for sacrifices, positioning dharma as karma-mārga, the path of dutiful action that ritually upholds ṛta against disorder.[39] The Atharvaveda incorporates dharma into protective rites and charms, broadening it to include spells for harmony in daily life and societal stability.[40] Smṛti texts systematize Vedic dharma into codified duties, with the Manusmṛti (composed circa 200 BCE to 200 CE) exemplifying this by enumerating sources such as śruti (Vedic revelation), smṛti itself, ācāra (practices of the virtuous), and ātmatuṣṭi (personal conviction aligned with conscience).[41] This text frames dharma as an operational ethic derived from primordial injunctions, emphasizing its role in guiding conduct to preserve cosmic and social equilibrium without deviation from revealed norms. Other Smṛtis, like the Yājñavalkya Smṛti, reinforce this by compiling ritual and ethical prescriptions, ensuring dharma's applicability across contexts while rooted in Vedic primacy.[42] The Pūrva Mīmāṃsā school exegetically prioritizes dharma as the realm of Vedic rituals (karma-kāṇḍa), interpreting it as eternal injunctions (vidhi) that generate apūrva, a subtle potency yielding fruits like heavenly rewards through precise observance.[43] This ritual-centric view posits dharma's efficacy in action over speculation, with texts like Jaimini's Mīmāṃsā Sūtras (circa 300 BCE) arguing that Vedic commands alone validate duties, dismissing deities as nominal for ritual validity. In synthesis with Uttara Mīmāṃsā (Vedānta), dharma acquires metaphysical depth, as articulated in Śaṅkara's commentaries, where ethical adherence aligns the practitioner with Brahman, transcending ritual to realize non-dual essence while provisional duties aid preparatory purification.[44] Patañjali's Yoga Sūtras (compiled circa 2nd–4th century CE) integrate dharma into practical discipline via yama (universal restraints like non-violence and truthfulness) and niyama (personal observances such as purity and contentment), forming the foundational limbs for citta-śuddhi (mind purification) essential to yoga's soteriological path.[45] These precepts operationalize dharma as self-restraint and cultivation, countering kleśas (afflictions) to facilitate samādhi, with their observance yielding both worldly harmony and progress toward kaivalya (isolation of pure consciousness).[46]Varnashrama Dharma and Social Order

Varnashrama Dharma constitutes the structural framework within Hindu tradition for organizing society through the division of labor into four varnas (functional classes) and four ashrams (life stages), each with prescribed duties aimed at maintaining interdependence and order. The varna system originates in the Rigveda's Purusha Sukta (10.90), which metaphorically describes the cosmic Purusha (primordial being) from whose mouth emerge the Brahmins, tasked with teaching, ritual performance, and knowledge preservation; from whose arms the Kshatriyas, responsible for governance, protection, and warfare; from whose thighs the Vaishyas, focused on agriculture, trade, and wealth generation; and from whose feet the Shudras, dedicated to manual labor and service to the other varnas.[47] This delineation aligns societal roles with inherent aptitudes, fostering specialization that sustains collective welfare without centralized coercion. The ashrama system complements varna by sequencing individual duties across life phases: Brahmacharya emphasizes celibate study under a guru to acquire Vedic knowledge and self-discipline; Grihastha involves marriage, family sustenance, and economic contribution to support the other ashrams through alms and progeny; Vanaprastha entails gradual withdrawal from worldly affairs for mentoring and forest-dwelling contemplation; and Sannyasa prioritizes renunciation and pursuit of moksha (liberation).[48] Together, varnashrama prescribes duties contingent on both functional aptitude and temporal stage, theorizing that such alignment minimizes conflict by channeling human inclinations toward productive ends rather than indiscriminate ambition. Empirical records indicate this system's contribution to societal cohesion in pre-colonial India, where decentralized kingdoms maintained continuity over millennia—from the Vedic period circa 1500 BCE through the Gupta Empire's peak in the 4th-5th centuries CE—despite external invasions, yielding advancements in mathematics (e.g., Aryabhata's heliocentric insights in 499 CE) and textual preservation without widespread internal upheavals. Oral transmission of the Vedas remained intact for over 3,000 years, verifiable through phonetic consistency across recensions, attributable to Brahmin specialization in memorization and ritual.[47] In contrast, historical egalitarian experiments, such as certain post-colonial collectivizations, correlated with economic disruptions and famines (e.g., India's 1960s shortages amid policy shifts away from traditional agrarian roles), underscoring the causal efficacy of aptitude-based specialization in averting resource misallocation. Critiques portraying varnashrama as rigidly hereditary overlook textual provisions for mobility based on guna (innate qualities) and karma (actions), as articulated in the Bhagavad Gita 4.13: "The four categories of occupations were created by Me according to people’s qualities and activities."[49] Instances include Vishwamitra's elevation from Kshatriya to Brahmin through ascetic rigor and Valmiki's transformation from a hunter to sage via penance, demonstrating exceptions for demonstrated aptitude over natal origin.[33] This flexibility, rooted in functional merit, underpinned the system's resilience, enabling knowledge custodianship amid dynastic changes and averting the societal entropy observed in less stratified ancient civilizations like Mesopotamia's frequent collapses.[49]Ethical and Legal Dimensions

The Dharma-shastras constitute a corpus of ancient Indian texts that codify positive law, deriving authority from scriptural smriti traditions and established customs to regulate social conduct, familial relations, and dispute resolution.[50] These treatises, including works attributed to Manu and Yajnavalkya, prescribe enforceable norms on inheritance, contracts, and penalties, functioning as a jurisprudence that integrates moral imperatives with practical governance.[51] Unlike purely revelatory shruti, the Dharma-shastras adapt Vedic principles to societal exigencies, emphasizing judicial processes where kings or assemblies adjudicated based on evidence and precedent.[52] Central to this legal framework is dandaniti, the science of punishment and state enforcement, which views danda (coercive sanction) as essential for upholding dharma against violations that disrupt cosmic and social order.[53] In Kautilya's Arthashastra (circa 4th century BCE, with later redactions), dandaniti integrates dharma with realpolitik, mandating rulers to impose graduated penalties—fines, corporal punishment, or exile—proportional to offenses, thereby deterring chaos and preserving societal stability.[54] This approach posits punishment not merely as retribution but as a corrective mechanism aligned with karma, where state intervention mirrors natural causal consequences to enforce ethical compliance.[55] Ethically, dharma prioritizes moral law within the purusharthas—the quartet of human aims encompassing dharma (righteousness), artha (prosperity), kama (pleasure), and moksha (liberation)—serving as the foundational restraint to prevent the unchecked pursuit of material goals from inducing societal decay.[56] Texts assert that subordinating artha and kama to dharma sustains long-term order, as ethical lapses erode trust and invite retribution through violated causal chains, evidenced in scriptural warnings of dynastic collapse absent righteous rule.[57] This prioritization fostered enduring traditions of communal trust, where customary adjudication minimized disputes without expansive bureaucracies, contrasting with critiques of inherent inequalities in varnashrama frameworks.[58] Criticisms portraying dharma-based systems as perpetuating hierarchy overlook empirical patterns where traditional social controls correlated with lower reported deviance; for instance, post-colonial declines in familial and caste-based oversight paralleled rises in cognizable offenses, from 367.5 per 100,000 in 2014 to 379.3 in 2017, suggesting dharma's integrative ethics contributed to restraint in pre-modern contexts.[59] Such mechanisms, rooted in reciprocal duties, empirically supported lower violent crime prevalence in cohesive communities adhering to scriptural norms, countering narratives of systemic oppression by highlighting functional stability over egalitarian ideals unsubstantiated by historical data.[60]Intersections with Life Stages and Poverty