Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spice trade

View on Wikipedia

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in the Eastern World.[1] These spices found their way into the Near East before the beginning of the Christian era, with fantastic tales hiding their true sources.[1]

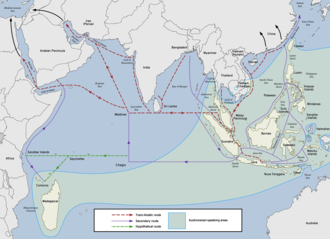

The maritime aspect of the trade was dominated by the Austronesian peoples in Southeast Asia, namely the ancient Indonesian sailors who established routes from Southeast Asia to Sri Lanka and India (and later China) by 1500 BC.[2] These goods were then transported by land toward the Mediterranean and the Greco-Roman world via the incense route and the Roman–India routes by Indian and Persian traders.[3] The Austronesian maritime trade lanes later expanded into the Middle East and eastern Africa by the 1st millennium AD, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar.

Within specific regions, the Kingdom of Axum (5th century BC – 11th century AD) had pioneered the Red Sea route before the 1st century AD. During the first millennium AD, Ethiopians became the maritime trading power of the Red Sea. By this period, trade routes existed from Sri Lanka (the Roman Taprobane) and India, which had acquired maritime technology from early Austronesian contact. By the mid-7th century AD, after the rise of Islam, Arab traders started plying these maritime routes and dominated the western Indian Ocean maritime routes.[citation needed]

Arab traders eventually took over conveying goods via the Levant and Venetian merchants to Europe until the rise of the Seljuk Turks in 1090. Later the Ottoman Turks held the route again by 1453 respectively. Overland routes helped the spice trade initially, but maritime trade routes led to tremendous growth in commercial activities to Europe. [citation needed]

The trade was changed by the Crusades and later the European Age of Discovery,[4] during which the spice trade, particularly in black pepper, became an influential activity for European traders.[5] From the 11th to the 15th centuries, the Italian maritime republics of Venice and Genoa monopolized the trade between Europe and Asia.[6] The Cape Route from Europe to the Indian Ocean via the Cape of Good Hope was pioneered by the Portuguese explorer navigator Vasco da Gama in 1498, resulting in new maritime routes for trade.[7]

This trade, which drove world trade from the end of the Middle Ages well into the Renaissance,[5] ushered in an age of European domination in the East.[7] Channels such as the Bay of Bengal served as bridges for cultural and commercial exchanges between diverse cultures[4] as nations struggled to gain control of the trade along the many spice routes.[1] In 1571 the Spanish opened the first trans-Pacific route between its territories of the Philippines and Mexico, served by the Manila Galleon. This trade route lasted until 1815. The Portuguese trade routes were mainly restricted and limited by the use of ancient routes, ports, and nations that were difficult to dominate. The Dutch were later able to bypass many of these problems by pioneering a direct ocean route from the Cape of Good Hope to the Sunda Strait in Indonesia.

Origins

[edit]

People in the Indian Ocean and Island Southeast Asia traded in spices, obsidian, seashells, gemstones and other high-value materials as early as the 10th millennium BC. The first to mention the trade in historical periods are the ancient Egyptians. In the 3rd millennium BC, they traded with the Land of Punt, which is believed to have been situated in an area encompassing northern Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea and the Red Sea coast of Sudan.[8][9]

The spice trade was initially associated with overland routes, but maritime routes proved to be the factor that helped the trade grow.[1] The first true maritime trade network in the Indian Ocean was by the Austronesian peoples of Maritime Southeast Asia.[10] They established trade routes with South India and Sri Lanka from around 1500 BC to 600 BC, ushering an exchange of material culture (like catamarans, outrigger boats, lashed-lug boats, sewn boats, and sampans) and cultigens (like coconuts, sandalwood, bananas, and sugarcane), as well as spices endemic to the Maluku Islands (cloves and nutmeg). It also connected the material cultures of India and China later on via the Maritime Silk Road. Ethnic groups in Indonesia in particular were trading in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa using catamaran and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the westerlies in the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded to reach as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by the first half of the first millennium AD. It continued into historic times, later becoming the Maritime Silk Road.[11][12][10][13][14][15][16][17]

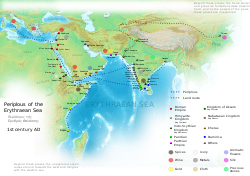

In the first millennium BC, Arabs, Phoenicians, and Indians were also engaged in sea and land trade in luxury goods such as spices, gold, precious stones, leather of exotic animals, ebony and pearls. Maritime trade was in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. The sea route in the Red Sea was from Bab-el-Mandeb to Berenice Troglodytica in Upper Egypt, from there inland to the Nile, and then by boat to Alexandria. Luxury goods like Indian spices, ebony, silk and fine textiles were traded along the overland Incense Route.[1]

In the second half of the first millennium BC the tribes of South and West Arabia took control over the land trade of spices from South Arabia to the Mediterranean Sea. These established Ma'in, Qataban, Hadhramaut, Sheba, and Himyar. In the north, the Nabateans took control of the trade route that crossed the Negev from Petra to Gaza. The trade enriched these tribes. South Arabia was called Eudaemon Arabia (the elated Arabia) by the ancient Greeks and was on the agenda of Alexander the Great before he died. Indians and the Arabs controlled the sea trade with India. In the late second century BC, the Greeks from the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt learned from the Indians how to sail directly from Aden to the west coast of India using the monsoon winds (as did Hippalus) and took control of the sea trade via Red Sea ports.[18]

Spices are discussed in biblical narratives, and there is literary evidence for their use in ancient Greek and Roman society. There is a record from Tamil texts of Greeks purchasing large sacks of black pepper from India, and many recipes in the 1st-century Roman cookbook Apicius make use of the spice. The trade in spices lessened after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but demand for ginger, black pepper, cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg revived the trade in later centuries.[19]

Arab trade and medieval Europe

[edit]

Rome played a part in the spice trade during the 5th century, but this role did not last through the Middle Ages.[1] The rise of Islam brought a significant change to the trade as Radhanite Jewish and Arab merchants, particularly from Egypt, eventually took over conveying goods via the Levant to Europe. At times, Jews enjoyed a virtual monopoly on the spice trade in large parts of Western Europe.[20]

The spice trade had brought great riches to the Abbasid Caliphate and inspired famous legends such as that of Sinbad the Sailor. These early sailors and merchants would often set sail from the port city of Basra and, after many ports of call, would return to sell their goods, including spices, in Baghdad. The fame of many spices such as nutmeg and cinnamon are attributed to these early spice merchants.[21][failed verification]

The Indian commercial connection with South East Asia proved vital to the merchants of Arabia and Persia during the 7th and 8th centuries.[22] Arab traders — mainly descendants of sailors from Yemen and Oman — dominated maritime routes throughout the Indian Ocean, tapping source regions in the Far East and linking to the secret "spice islands" (Maluku Islands and Banda Islands). The islands of Molucca also find mention in several records: a Javanese chronicle (1365) mentions the Moluccas and Maloko, and navigational works of the 14th and 15th centuries contain the first unequivocal Arab reference to Moluccas. Sulaima al-Mahr writes: "East of Timor [where sandalwood is found] are the islands of Bandam and they are the islands where nutmeg and mace are found. The islands of cloves are called Maluku ....."[23]

Moluccan products were shipped to trading emporiums in India, passing through ports like Kozhikode in Kerala and through Sri Lanka. From there they were shipped westward across the ports of Arabia to the Near East, to Ormus in the Persian Gulf and Jeddah in the Red Sea and sometimes to East Africa, where they were used for many purposes, including burial rites.[24] The Abbasids used Alexandria, Damietta, Aden and Siraf as entry ports to trade with India and China.[25] Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden paid tribute in form of musk, camphor, ambergris and sandalwood to Ibn Ziyad, the sultan of Yemen.[25]

Indian spice exports find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850), al-Ghafiqi (1150), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (14th century).[24] Chinese traveler Xuanzang mentions the town of Puri where "merchants depart for distant countries."[26]

From there, overland routes led to the Mediterranean coasts. From the 8th until the 15th century, maritime republics (Republic of Venice, Republic of Pisa, Republic of Genoa, Duchy of Amalfi, Duchy of Gaeta, Republic of Ancona and Republic of Ragusa[27]) held a monopoly on European trade with the Middle East. The silk and spice trade, involving spices, incense, herbs, drugs and opium, made these Mediterranean city-states extremely wealthy. Spices were among the most expensive and in-demand products of the Middle Ages, used in medicine as well as in the kitchen. They were all imported from Asia and Africa. Venetian and other navigators of maritime republics then distributed the goods through Europe.

Age of Discovery: a new route and a New World

[edit]

The Republic of Venice had become a formidable power and a key player in the Eastern spice trade.[28] Other powers, in an attempt to break the Venetian hold on spice trade, began to build up maritime capability.[1] Until the mid-15th century, trade with the East was achieved through the Silk Road, with the Byzantine Empire and the Italian city-states of Venice and Genoa acting as middlemen.

The first country to attempt to circumnavigate Africa was Portugal, which had, since the early 15th century, begun to explore northern Africa under Henry the Navigator. Emboldened by these early successes and eyeing a lucrative monopoly on a possible sea route to the Indies, the Portuguese first rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 on an expedition led by Bartolomeu Dias.[29] Just nine years later in 1497, on the orders of Manuel I of Portugal, four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama continued beyond to the eastern coast of Africa to Malindi and sailed across the Indian Ocean to Calicut, on the Malabar Coast in Kerala[7] in South India — the capital of the local Zamorin rulers. The wealth of the Indies was now open for the Europeans to explore; the Portuguese Empire was the earliest European seaborne empire to grow from the spice trade.[7]

In 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca for Portugal, then the center of Asian trade. East of Malacca, Albuquerque sent several diplomatic and exploratory missions, including to the Moluccas. Learning the secret location of the Spice Islands, mainly the Banda Islands, then the world source of nutmeg, he sent an expedition led by António de Abreu to Banda, where they were the first Europeans to arrive, in early 1512.[30] Abreu's expedition reached Buru, Ambon and Seram Islands, and then Banda.

From 1507 to 1515 Albuquerque tried to completely block Arab and other traditional routes that stretched from the shores of Western India to the Mediterranean Sea, through the conquest of strategic bases in the Persian Gulf and at the entry of the Red Sea. [citation needed]

By the early 16th century the Portuguese had complete control of the African sea route, which extended through a long network of routes that linked three oceans, from the Moluccas (the Spice Islands) in the Pacific Ocean limits, through Malacca, Kerala and Sri Lanka, to Lisbon in Portugal. [citation needed]

The Crown of Castile had organized the expedition of Christopher Columbus to compete with Portugal for the spice trade with Asia, but when Columbus landed on the island of Hispaniola (in what is now Haiti) instead of in the Indies, the search for a route to Asia was postponed until a few years later. After Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama in 1513, the Spanish Crown prepared a westward voyage by Ferdinand Magellan in order to reach Asia from Spain across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. On October 21, 1520, his expedition crossed the Strait of Magellan in the southern tip of South America, opening the Pacific to European exploration. On March 16, 1521, the ships reached the Philippines and soon after the Spice Islands, ultimately resulting decades later in the Manila Galleon trade, the first westward spice trade route to Asia. After Magellan's death in the Philippines, navigator Juan Sebastian Elcano took command of the expedition and drove it across the Indian Ocean and back to Spain, where they arrived in 1522 aboard the last remaining ship, the Victoria. For the next two-and-a-half centuries, Spain controlled a vast trade network that linked three continents: Asia, the Americas and Europe. A global spice route had been created: from Manila in the Philippines (Asia) to Seville in Spain (Europe), via Acapulco in Mexico (North America). [citation needed]

Cultural diffusion

[edit]

One of the most important technological exchanges of the spice trade network was the early introduction of maritime technologies to India, the Middle East, East Africa, and China by the Austronesian peoples. These technologies include the plank-sewn hulls, catamarans, outrigger boats, and possibly the lateen sail. This is still evident in Sri Lankan and South Indian languages. For example, Tamil paṭavu, Telugu paḍava, and Kannada paḍahu, all meaning "ship", are all derived from Proto-Hesperonesian *padaw, "sailboat", with Austronesian cognates like Javanese perahu, Kadazan padau, Maranao padaw, Cebuano paráw, Samoan folau, Hawaiian halau, and Māori wharau.[14][13][15]

Austronesians also introduced many Austronesian cultigens to southern India, Sri Lanka, and eastern Africa that figured prominently in the spice trade.[31] They include bananas,[32] Pacific domesticated coconuts,[33][34] Dioscorea yams,[35] wetland rice,[32] sandalwood,[36] giant taro,[37] Polynesian arrowroot,[38] ginger,[39] lengkuas,[31] tailed pepper,[40] betel,[12] areca nut,[12] and sugarcane.[41][42]

Hindu and Buddhist religious establishments of Southeast Asia came to be associated with economic activity and commerce as patrons, entrusted large funds which would later be used to benefit local economies by estate management, craftsmanship, and promotion of trading activities.[43] Buddhism, in particular, traveled alongside the maritime trade, promoting coinage, art, and literacy.[44] Islam spread throughout the East, reaching maritime Southeast Asia in the 10th century; Muslim merchants played a crucial part in the trade.[45] Christian missionaries, such as Saint Francis Xavier, were instrumental in the spread of Christianity in the East.[45] Christianity competed with Islam to become the dominant religion of the Moluccas.[45] However, the natives of the Spice Islands accommodated to aspects of both religions easily.[46]

The Portuguese colonial settlements saw traders, such as the Gujarati banias, South Indian Chettis, Syrian Christians, Chinese from Fujian province, and Arabs from Aden, involved in the spice trade.[47] Epics, languages, and cultural customs were borrowed by Southeast Asia from India, and later China.[4] Knowledge of Portuguese language became essential for merchants involved in the trade.[48] The colonial pepper trade drastically changed the experience of modernity in Europe, and in Kerala and it brought, along with colonialism, early capitalism to India's Malabar Coast, changing cultures of work and caste.[49]

Indian merchants involved in spice trade took Indian cuisine to Southeast Asia, notably present day Malaysia and Indonesia, where spice mixtures and black pepper became popular.[50] Conversely, Southeast Asian cuisine and crops was also introduced to India and Sri Lanka, where rice cakes and coconut milk-based dishes are still dominant.[31][33][32][39][51]

European people intermarried with Indians and popularized valuable culinary skills, such as baking, in India.[52] Indian food, adapted to the European palate, became visible in England by 1811 as exclusive establishments began catering to the tastes of both the curious and those returning from India.[53] Opium was a part of the spice trade, and some people involved in the spice trade were driven by opium addiction.[54][55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Spice Trade". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Dick-Read, Robert (July 2006). "Indonesia and Africa: questioning the origins of some of Africa's most famous icons". The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa. 2 (1): 23–45. doi:10.4102/td.v2i1.307.

- ^ Fage 1975: 164

- ^ a b c Donkin 2003

- ^ a b Corn & Glasserman 1999: Prologue

- ^ "Brainy IAS - Online & Offline Classes". Brainy IAS. 2018-03-03. Retrieved 2021-09-22.

- ^ a b c d Gama, Vasco da. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Simson Najovits, Egypt, trunk of the tree, Volume 2, (Algora Publishing: 2004), p. 258.

- ^ Rawlinson 2001: 11-12

- ^ a b c Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 978-3-319-33822-4.

- ^ Olivera, Baldomero; Hall, Zach; Granberg, Bertrand (31 March 2024). "Reconstructing Philippine history before 1521: the Kalaga Putuan Crescent and the Austronesian maritime trade network". SciEnggJ. 17 (1): 71–85. doi:10.54645/2024171ZAK-61.

- ^ a b c Zumbroich, Thomas J. (2007–2008). "The origin and diffusion of betel chewing: a synthesis of evidence from South Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond". eJournal of Indian Medicine. 1: 87–140. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b Doran, Edwin Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140.

- ^ a b Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 0-415-10054-2.[dead link]

- ^ a b Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-107-0.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- ^ Daniels, Christian; Menzies, Nicholas K. (1996). Needham, Joseph (ed.). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 3, Agro-Industries and Forestry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–185. ISBN 978-0-521-41999-4.

- ^ Shaw 2003: 426

- ^ The Medieval Spice Trade and the Diffusion of the Chile Gastronomica Spring 2007 Vol. 7 Issue 2

- ^ Rabinowitz, Louis (1948). Jewish Merchant Adventurers: A Study of the Radanites. London: Edward Goldston. pp. 150–212.

- ^ "The Third Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman – The Arabian Nights – The Thousand and One Nights – Sir Richard Burton translator". Classiclit.about.com. 2009-11-02. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Donkin 2003: 59

- ^ Donkin 2003: 88

- ^ a b Donkin 2003: 92

- ^ a b Donkin 2003: 91–92

- ^ Donkin 2003: 65

- ^ Armando Lodolini, Le repubbliche del mare, Roma, Biblioteca di storia patria, 1967.

- ^ Pollmer, Priv.Doz. Dr. Udo. "The spice trade and its importance for European expansion". Migration and Diffusion. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Bartolomeu Dias Retrieved November 29, 2007

- ^ Nathaniel's Nutmeg: How One Man's Courage Changed the Course of History, Milton, Giles (1999), pp. 5–7

- ^ a b c Hoogervorst, Tom (2013). "If Only Plants Could talk...: Reconstructing Pre-Modern Biological Translocations in the Indian Ocean" (PDF). In Chandra, Satish; Prabha Ray, Himanshu (eds.). The Sea, Identity and History: From the Bay of Bengal to the South China Sea. Manohar. pp. 67–92. ISBN 978-81-7304-986-6.

- ^ a b c Lockard, Craig A. (2010). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History. Cengage Learning. pp. 123–125. ISBN 978-1-4390-8520-2.

- ^ a b Gunn, Bee F.; Baudouin, Luc; Olsen, Kenneth M.; Ingvarsson, Pär K. (22 June 2011). "Independent Origins of Cultivated Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in the Old World Tropics". PLOS ONE. 6 (6) e21143. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621143G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021143. PMC 3120816. PMID 21731660.

- ^ Crowther, Alison; Lucas, Leilani; Helm, Richard; Horton, Mark; Shipton, Ceri; Wright, Henry T.; Walshaw, Sarah; Pawlowicz, Matthew; Radimilahy, Chantal; Douka, Katerina; Picornell-Gelabert, Llorenç; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Boivin, Nicole L. (14 June 2016). "Ancient crops provide first archaeological signature of the westward Austronesian expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (24): 6635–6640. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.6635C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1522714113. PMC 4914162. PMID 27247383.

- ^ Barker, Graeme; Hunt, Chris; Barton, Huw; Gosden, Chris; Jones, Sam; Lloyd-Smith, Lindsay; Farr, Lucy; Nyirí, Borbala; O'Donnell, Shawn (August 2017). "The 'cultured rainforests' of Borneo" (PDF). Quaternary International. 448: 44–61. Bibcode:2017QuInt.448...44B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.08.018.

- ^ Fox, James J. (2006). Inside Austronesian Houses: Perspectives on Domestic Designs for Living. ANU E Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-920942-84-7.

- ^ Matthews, Peter J. (1995). "Aroids and the Austronesians". Tropics. 4 (2/3): 105–126. Bibcode:1995Tropi...4..105M. doi:10.3759/tropics.4.105.

- ^ Spennemann, Dirk H.R. (1994). "Traditional Arrowroot Production and Utilization in the Marshall Islands". Journal of Ethnobiology. 14 (2): 211–234.

- ^ a b Viestad A (2007). Where Flavor Was Born: Recipes and Culinary Travels Along the Indian Ocean Spice Route. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8118-4965-4.

- ^ Ravindran, P.N. (2017). The Encyclopedia of Herbs and Spices. CABI. ISBN 978-1-78064-315-1.

- ^ Daniels, John; Daniels, Christian (April 1993). "Sugarcane in Prehistory". Archaeology in Oceania. 28 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1993.tb00309.x.

- ^ Paterson, Andrew H.; Moore, Paul H.; Tom L., Tew (2012). "The Gene Pool of Saccharum Species and Their Improvement". In Paterson, Andrew H. (ed.). Genomics of the Saccharinae. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 43–72. ISBN 978-1-4419-5947-8.

- ^ Donkin 2003: 67

- ^ Donkin 2003: 69

- ^ a b c Corn & Glasserman 1999

- ^ Corn & Glasserman 1999: 105

- ^ Collingham 56: 2006

- ^ Corn & Glasserman 1999: 203

- ^ Vinod Kottayil Kalidasan, 'The Routes of Pepper: Colonial Discourses around the Spice Trade in Malabar', Kerala Modernity: Ideasa, Spaces and Practices in Transition, Ed. Shiju Sam Varughese and Satheese Chandra Bose, New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2015. For the link: "Orient Blackswan PVT. LTD". Archived from the original on 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

- ^ Collingham 245: 2006

- ^ Dalby A (2002). Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23674-5.

- ^ Collingham 61: 2006

- ^ Collingham 129: 2006

- ^ "Opium Throughout History | The Opium Kings | FRONTLINE". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- ^ Burger, M. (2003), The Forgotten Gold? The Importance of the Dutch opium trade in the Seventeenth Century

Bibliography

[edit]- Collingham, Lizzie (December 2005). Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517241-6.

- Corn, Charles; Debbie Glasserman (March 1999). The Scents of Eden: A History of the Spice Trade. Kodansha America. ISBN 978-1-56836-249-6.

- Donkin, Robin A. (August 2003). Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87169-248-1.

- Fage, John Donnelly; et al. (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3.

- Rawlinson, Hugh George (2001). Intercourse Between India and the Western World: From the Earliest Times of the Fall of Rome. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1549-6.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- Kalidasan, Vinod Kottayil (2015). "Routes of Pepper: Colonial Discourses around Spice Trade in Malabar" in Kerala Modernity: Ideas, Spaces and Practices in Transition, Shiju Sam Varughese and Sathese Chandra Bose (Eds). Orient Blackswan, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-250-5722-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Borschberg, Peter (2017), "The Value of Admiral Matelieff's Writings for Studying the History of Southeast Asia, c. 1600–1620". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 48(3): 414–435. doi:10.1017/S002246341700056X.

- Keay, John (2006). The Spice Route: A History. University of California Press.

- Nabhan, Gary Paul: Cumin, Camels, and Caravans: A Spice Odyssey. [History of Spice Trade] University of California Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-520-26720-6 [Print]; ISBN 978-0-520-95695-7 [eBook]

- Pavo López, Marcos: Spices in maps. Fifth centenary of the first circumnavigation of the world. [History of the spice trade through old maps] e-Perimetron, vol 15, no.2 (2020)