Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Arabic

View on Wikipedia

Arabic[c] is a Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world.[13] The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns language codes to 32 varieties of Arabic, including its standard form of Literary Arabic, known as Modern Standard Arabic,[14] which is derived from Classical Arabic. This distinction exists primarily among Western linguists; Arabic speakers themselves generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, but rather refer to both as al-ʿarabiyyatu l-fuṣḥā (اَلعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ[15] "the eloquent Arabic") or simply al-fuṣḥā (اَلْفُصْحَىٰ).

Arabic is the third most widespread official language after English and French,[16] one of six official languages of the United Nations,[17] and the liturgical language of Islam.[18] Arabic is widely taught in schools and universities around the world and is used to varying degrees in workplaces, governments and the media.[18] During the Middle Ages, Arabic was a major vehicle of culture and learning, especially in science, mathematics and philosophy. As a result, many European languages have borrowed words from it. Arabic influence, mainly in vocabulary, is seen in European languages (mainly Spanish and to a lesser extent Portuguese, Catalan, and Sicilian) owing to the proximity of Europe and the long-lasting Arabic cultural and linguistic presence, mainly in Southern Iberia, during the Al-Andalus era. Maltese is a Semitic language developed from a dialect of Arabic and written in the Latin alphabet.[19] The Balkan languages, including Albanian, Greek, Serbo-Croatian, and Bulgarian, have also acquired many words of Arabic origin, mainly through direct contact with Ottoman Turkish.

Arabic has influenced languages across the globe throughout its history, especially languages where Islam is the predominant religion and in countries that were conquered by Muslims. The most markedly influenced languages are Persian, Turkish, Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu),[20] Kashmiri, Kurdish, Bosnian, Kazakh, Bengali, Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Maldivian, Pashto, Punjabi, Albanian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Sicilian, Spanish, Greek, Bulgarian, Tagalog, Sindhi, Odia,[21] Hebrew and African languages such as Hausa, Amharic, Tigrinya, Somali, Tamazight, and Swahili. Conversely, Arabic has borrowed some words (mostly nouns) from other languages, including its sister-language Aramaic, Persian, Greek, and Latin and to a lesser extent and more recently from Turkish, English, French, and Italian.

Arabic is spoken by as many as 380 million speakers, both native and non-native, in the Arab world,[1] making it the fifth most spoken language in the world[22] and the fourth most used language on the Internet in terms of users.[23][24] It also serves as the liturgical language of more than 2 billion Muslims.[17] In 2011, Bloomberg Businessweek ranked Arabic the fourth most useful language for business, after English, Mandarin Chinese, and French.[25] Arabic is written with the Arabic alphabet, an abjad script that is written from right to left.

Classical Arabic (and Modern Standard Arabic) is considered a conservative language among Semitic languages, it preserved the complete Proto-Semitic three grammatical cases and declension (ʾiʿrāb), and it was used in the reconstruction of Proto-Semitic since it preserves as contrastive 28 out of the evident 29 consonantal phonemes.[26]

Classification

[edit]Arabic is usually classified as a Central Semitic language. Linguists still differ as to the best classification of Semitic language sub-groups.[27] The Semitic languages changed between Proto-Semitic and the emergence of Central Semitic languages, particularly in grammar. Innovations of the Central Semitic languages—all maintained in Arabic—include:

- The conversion of the suffix-conjugated stative formation (jalas-) into a past tense.

- The conversion of the prefix-conjugated preterite-tense formation (yajlis-) into a present tense.

- The elimination of other prefix-conjugated mood/aspect forms (e.g., a present tense formed by doubling the middle root, a perfect formed by infixing a /t/ after the first root consonant, probably a jussive formed by a stress shift) in favor of new moods formed by endings attached to the prefix-conjugation forms (e.g., -u for indicative, -a for subjunctive, no ending for jussive, -an or -anna for energetic).

- The development of an internal passive.

There are several features which Classical Arabic, the modern Arabic varieties, as well as the Safaitic and Hismaic inscriptions share which are unattested in any other Central Semitic language variety, including the Dadanitic and Taymanitic languages of the northern Hejaz. These features are evidence of common descent from a hypothetical ancestor, Proto-Arabic.[28][29] The following features of Proto-Arabic can be reconstructed with confidence:[30]

- negative particles m * /mā/; lʾn */lā-ʾan/ to Classical Arabic lan

- mafʿūl G-passive participle

- prepositions and adverbs f, ʿn, ʿnd, ḥt, ʿkdy

- a subjunctive in -a

- t-demonstratives

- leveling of the -at allomorph of the feminine ending

- ʾn complementizer and subordinator

- the use of f- to introduce modal clauses

- independent object pronoun in (ʾ)y

- vestiges of nunation

On the other hand, several Arabic varieties are closer to other Semitic languages and maintain features not found in Classical Arabic, indicating that these varieties cannot have developed from Classical Arabic.[31][32] Thus, Arabic vernaculars do not descend from Classical Arabic:[33] Classical Arabic is a sister language rather than their direct ancestor.[28]

History

[edit]Old Arabic

[edit]Arabia had a wide variety of Semitic languages in antiquity. The term "Arab" was initially used to describe those living in Mesopotamia, Levant, Sinai, and the Arabian Peninsula, as perceived by geographers from ancient Greece.[13][34] In the southwest, various Central Semitic languages both belonging to and outside the Ancient South Arabian family (e.g. Southern Thamudic) were spoken. It is believed that the ancestors of the Modern South Arabian languages (non-Central Semitic languages) were spoken in southern Arabia at this time. To the north, in the oases of northern Hejaz, Dadanitic and Taymanitic held some prestige as inscriptional languages. In Najd and parts of western Arabia, a language known to scholars as Thamudic C is attested.[13]

In eastern Arabia, inscriptions in a script derived from ASA attest to a language known as Hasaitic. On the northwestern frontier of Arabia, various languages known to scholars as Thamudic B, Thamudic D, Safaitic, and Hismaic are attested. The last two share important isoglosses with later forms of Arabic, leading scholars to theorize that Safaitic and Hismaic are early forms of Arabic and that they should be considered Old Arabic.[13]

Linguists generally believe that "Old Arabic", a collection of related dialects that constitute the precursor of Arabic, first emerged during the Iron Age.[27] Previously, the earliest attestation of Old Arabic was thought to be a single 1st century CE inscription in Sabaic script at Qaryat al-Faw, in southern present-day Saudi Arabia. However, this inscription does not participate in several of the key innovations of the Arabic language group, such as the conversion of Semitic mimation to nunation in the singular. It is best reassessed as a separate language on the Central Semitic dialect continuum.[35]

It was also thought that Old Arabic coexisted alongside—and then gradually displaced—epigraphic Ancient North Arabian (ANA), which was theorized to have been the regional tongue for many centuries. ANA, despite its name, was considered a very distinct language, and mutually unintelligible, from "Arabic". Scholars named its variant dialects after the towns where the inscriptions were discovered (Dadanitic, Taymanitic, Hismaic, Safaitic).[27] However, most arguments for a single ANA language or language family were based on the shape of the definite article, a prefixed h-. It has been argued that the h- is an archaism and not a shared innovation, and thus unsuitable for language classification, rendering the hypothesis of an ANA language family untenable.[36] Safaitic and Hismaic, previously considered ANA, should be considered Old Arabic due to the fact that they participate in the innovations common to all forms of Arabic.[13]

The earliest attestation of continuous Arabic text in an ancestor of the modern Arabic script are three lines of poetry by a man named Garm(')allāhe found in En Avdat, Israel, and dated to around 125 CE.[37] This is followed by the Namara inscription, an epitaph of the Lakhmid king Imru' al-Qays bar 'Amro, dating to 328 CE, found at Namaraa, Syria. From the 4th to the 6th centuries, the Nabataean script evolved into the Arabic script recognizable from the early Islamic era.[38] There are inscriptions in an undotted, 17-letter Arabic script dating to the 6th century CE, found at four locations in Syria (Zabad, Jebel Usays, Harran, Umm el-Jimal). The oldest surviving papyrus in Arabic dates to 643 CE, and it uses dots to produce the modern 28-letter Arabic alphabet. The language of that papyrus and of the Qur'an is referred to by linguists as "Quranic Arabic", as distinct from its codification soon thereafter into "Classical Arabic".[27]

Classical Arabic

[edit]In late pre-Islamic times, a transdialectal and transcommunal variety of Arabic emerged in the Hejaz, which continued living its parallel life after literary Arabic had been institutionally standardized in the 2nd and 3rd century of the Hijra, most strongly in Judeo-Christian texts, keeping alive ancient features eliminated from the "learned" tradition (Classical Arabic).[39] This variety and both its classicizing and "lay" iterations have been termed Middle Arabic in the past, but they are thought to continue an Old Higazi register. It is clear that the orthography of the Quran was not developed for the standardized form of Classical Arabic; rather, it shows the attempt on the part of writers to record an archaic form of Old Higazi.[citation needed]

In the late 6th century AD, a relatively uniform intertribal "poetic koine" distinct from the spoken vernaculars developed based on the Bedouin dialects of Najd, probably in connection with the court of al-Ḥīra. During the first Islamic century, the majority of Arabic poets and Arabic-writing persons spoke Arabic as their mother tongue. Their texts, although mainly preserved in far later manuscripts, contain traces of non-standardized Classical Arabic elements in morphology and syntax.[citation needed]

Standardization

[edit]Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali (c. 603–689) is credited with standardizing Arabic grammar, or an-naḥw (النَّحو "the way"[40]), and pioneering a system of diacritics to differentiate consonants (نقط الإعجام nuqaṭu‿l-i'jām "pointing for non-Arabs") and indicate vocalization (التشكيل at-tashkīl).[41] Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi (718–786) compiled the first Arabic dictionary, Kitāb al-'Ayn (كتاب العين "The Book of the Letter ع"), and is credited with establishing the rules of Arabic prosody.[42] Al-Jahiz (776–868) proposed to Al-Akhfash al-Akbar an overhaul of the grammar of Arabic, but it would not come to pass for two centuries.[43] The standardization of Arabic reached completion around the end of the 8th century. The first comprehensive description of the ʿarabiyya "Arabic", Sībawayhi's al-Kitāb, is based first of all upon a corpus of poetic texts, in addition to Qur'an usage and Bedouin informants whom he considered to be reliable speakers of the ʿarabiyya.[44]

Spread

[edit]Arabic spread with the spread of Islam. Following the early Muslim conquests, Arabic gained vocabulary from Middle Persian and Turkish.[45] In the early Abbasid period, many Classical Greek terms entered Arabic through translations carried out at Baghdad's House of Wisdom.[45]

By the 8th century, knowledge of Classical Arabic had become an essential prerequisite for rising into the higher classes throughout the Islamic world, both for Muslims and non-Muslims. For example, Maimonides, the Andalusi Jewish philosopher, authored works in Judeo-Arabic—Arabic written in Hebrew script.[46]

Development

[edit]Ibn Jinni of Mosul, a pioneer in phonology, wrote prolifically in the 10th century on Arabic morphology and phonology in works such as Kitāb Al-Munṣif, Kitāb Al-Muḥtasab, and Kitāb Al-Khaṣāʾiṣ .[47]

Ibn Mada' of Cordoba (1116–1196) realized the overhaul of Arabic grammar first proposed by Al-Jahiz 200 years prior.[43]

The Maghrebi lexicographer Ibn Manzur compiled Lisān al-ʿArab (لسان العرب, "Tongue of Arabs"), a major reference dictionary of Arabic, in 1290.[48]

Neo-Arabic

[edit]Charles Ferguson's koine theory claims that the modern Arabic dialects collectively descend from a single military koine that sprang up during the Islamic conquests; this view has been challenged in recent times. Ahmad al-Jallad proposes that there were at least two considerably distinct types of Arabic on the eve of the conquests: Northern and Central (Al-Jallad 2009). The modern dialects emerged from a new contact situation produced following the conquests. Instead of the emergence of a single or multiple koines, the dialects contain several sedimentary layers of borrowed and areal features, which they absorbed at different points in their linguistic histories.[44] According to Veersteegh and Bickerton, colloquial Arabic dialects arose from pidginized Arabic formed from contact between Arabs and conquered peoples. Pidginization and subsequent creolization among Arabs and arabized peoples could explain relative morphological and phonological simplicity of vernacular Arabic compared to Classical and MSA.[49][50]

In around the 11th and 12th centuries in al-Andalus, the zajal and muwashah poetry forms developed in the dialectical Arabic of Cordoba and the Maghreb.[51]

Nahda

[edit]The Nahda was a cultural and especially literary renaissance of the 19th century in which writers sought "to fuse Arabic and European forms of expression."[52] According to James L. Gelvin, "Nahda writers attempted to simplify the Arabic language and script so that it might be accessible to a wider audience."[52]

In the wake of the industrial revolution and European hegemony and colonialism, pioneering Arabic presses, such as the Amiri Press established by Muhammad Ali (1819), dramatically changed the diffusion and consumption of Arabic literature and publications.[53] Rifa'a al-Tahtawi proposed the establishment of Madrasat al-Alsun in 1836 and led a translation campaign that highlighted the need for a lexical injection in Arabic, to suit concepts of the industrial and post-industrial age (such as sayyārah سَيَّارَة 'automobile' or bākhirah باخِرة 'steamship').[54][55]

In response, a number of Arabic academies modeled after the Académie française were established with the aim of developing standardized additions to the Arabic lexicon to suit these transformations,[56] first in Damascus (1919), then in Cairo (1932), Baghdad (1948), Rabat (1960), Amman (1977), Khartum (1993), and Tunis (1993).[57] They review language development, monitor new words and approve the inclusion of new words into their published standard dictionaries.

In 1997, a bureau of Arabization standardization was added to the Educational, Cultural, and Scientific Organization of the Arab League.[57] These academies and organizations have worked toward the Arabization of the sciences, creating terms in Arabic to describe new concepts, toward the standardization of these new terms throughout the Arabic-speaking world, and toward the development of Arabic as a world language.[57] This gave rise to what Western scholars call Modern Standard Arabic. From the 1950s, Arabization became a postcolonial nationalist policy in countries such as Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco,[58] and Sudan.[59]

Classical, Modern Standard and spoken Arabic

[edit]Arabic usually refers to Standard Arabic, which Western linguists divide into Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic.[60] It could also refer to any of a variety of regional vernacular Arabic dialects, which are not necessarily mutually intelligible.

Classical Arabic is the language found in the Quran, used from the period of Pre-Islamic Arabia to that of the Abbasid Caliphate. Classical Arabic is prescriptive, according to the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh) and the vocabulary defined in classical dictionaries (such as the Lisān al-ʻArab).[citation needed]

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) largely follows the grammatical standards of Classical Arabic and uses much of the same vocabulary. However, it has discarded some grammatical constructions and vocabulary that no longer have any counterpart in the spoken varieties and has adopted certain new constructions and vocabulary from the spoken varieties. Much of the new vocabulary is used to denote concepts that have arisen in the industrial and post-industrial era, especially in modern times.[61]

Due to its grounding in Classical Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic is removed over a millennium from everyday speech, which is construed as a multitude of dialects of this language. These dialects and Modern Standard Arabic are described by some scholars as not mutually comprehensible. The former are usually acquired in families, while the latter is taught in formal education settings. However, there have been studies reporting some degree of comprehension of stories told in the standard variety among preschool-aged children.[61]

The relation between Modern Standard Arabic and these dialects is sometimes compared to that of Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin vernaculars (which became Romance languages) in medieval and early modern Europe.[60]

MSA is the variety used in most current, printed Arabic publications, spoken by some of the Arabic media across North Africa and the Middle East, and understood by most educated Arabic speakers. "Literary Arabic" and "Standard Arabic" (فُصْحَى fuṣḥá) are less strictly defined terms that may refer to Modern Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.[citation needed]

Some of the differences between Classical Arabic (CA) and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) are as follows:[citation needed]

- Certain grammatical constructions of CA that have no counterpart in any modern vernacular dialect (e.g., the energetic mood) are almost never used in Modern Standard Arabic.[citation needed]

- Case distinctions are very rare in Arabic vernaculars. As a result, MSA is generally composed without case distinctions in mind, and the proper cases are added after the fact, when necessary. Because most case endings are noted using final short vowels, which are normally left unwritten in the Arabic script, it is unnecessary to determine the proper case of most words. The practical result of this is that MSA, like English and Standard Chinese, is written in a strongly determined word order and alternative orders that were used in CA for emphasis are rare. In addition, because of the lack of case marking in the spoken varieties, most speakers cannot consistently use the correct endings in extemporaneous speech. As a result, spoken MSA tends to drop or regularize the endings except when reading from a prepared text.[citation needed]

- The numeral system in CA is complex and heavily tied in with the case system. This system is never used in MSA, even in the most formal of circumstances; instead, a greatly simplified system is used, approximating the system of the conservative spoken varieties.[citation needed]

MSA uses much Classical vocabulary (e.g., dhahaba 'to go') that is not present in the spoken varieties, but deletes Classical words that sound obsolete in MSA. In addition, MSA has borrowed or coined many terms for concepts that did not exist in Quranic times, and MSA continues to evolve.[62] Some words have been borrowed from other languages—notice that transliteration mainly indicates spelling and not real pronunciation (e.g., فِلْم film 'film' or ديمقراطية dīmuqrāṭiyyah 'democracy').[citation needed]

The current preference is to avoid direct borrowings, preferring to either use loan translations (e.g., فرع farʻ 'branch', also used for the branch of a company or organization; جناح janāḥ 'wing', is also used for the wing of an airplane, building, air force, etc.), or to coin new words using forms within existing roots (استماتة istimātah 'apoptosis', using the root موت m/w/t 'death' put into the Xth form, or جامعة jāmiʻah 'university', based on جمع jamaʻa 'to gather, unite'; جمهورية jumhūriyyah 'republic', based on جمهور jumhūr 'multitude'). An earlier tendency was to redefine an older word although this has fallen into disuse (e.g., هاتف hātif 'telephone' < 'invisible caller (in Sufism)'; جريدة jarīdah 'newspaper' < 'palm-leaf stalk').[citation needed]

Colloquial or dialectal Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties which constitute the everyday spoken language. Colloquial Arabic has many regional variants; geographically distant varieties usually differ enough to be mutually unintelligible, and some linguists consider them distinct languages.[63] However, research indicates a high degree of mutual intelligibility between closely related Arabic variants for native speakers listening to words, sentences, and texts; and between more distantly related dialects in interactional situations.[64]

The varieties are typically unwritten. They are often used in informal spoken media, such as soap operas and talk shows,[66] as well as occasionally in certain forms of written media such as poetry and printed advertising.

Hassaniya Arabic, Maltese, and Cypriot Arabic are only varieties of modern Arabic to have acquired official recognition.[67] Hassaniya is official in Mali[68] and recognized as a minority language in Morocco,[69] while the Senegalese government adopted the Latin script to write it.[11] Maltese is official in (predominantly Catholic) Malta and written with the Latin script. Linguists agree that it is a variety of spoken Arabic, descended from Siculo-Arabic, though it has experienced extensive changes as a result of sustained and intensive contact with Italo-Romance varieties, and more recently also with English. Due to "a mix of social, cultural, historical, political, and indeed linguistic factors", many Maltese people today consider their language Semitic but not a type of Arabic.[70] Cypriot Arabic is recognized as a minority language in Cyprus.[71]

Status and usage

[edit]Diglossia

[edit]The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia, which is the normal use of two separate varieties of the same language, usually in different social situations. Tawleed is the process of giving a new shade of meaning to an old classical word. For example, al-hatif lexicographically means the one whose sound is heard but whose person remains unseen. Now the term al-hatif is used for a telephone. Therefore, the process of tawleed can express the needs of modern civilization in a manner that would appear to be originally Arabic.[72]

In the case of Arabic, educated Arabs of any nationality can be assumed to speak both their school-taught Standard Arabic as well as their native dialects, which depending on the region may be mutually unintelligible.[73][74][75][76][77] Some of these dialects can be considered to constitute separate languages which may have "sub-dialects" of their own.[78] When educated Arabs of different dialects engage in conversation (for example, a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), many speakers code-switch back and forth between the dialectal and standard varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence.

The issue of whether Arabic is one language or many languages is politically charged, in the same way it is for the varieties of Chinese, Hindi and Urdu, Serbian and Croatian, Scots and English, etc. In contrast to speakers of Hindi and Urdu who claim they cannot understand each other even when they can, speakers of the varieties of Arabic will claim they can all understand each other even when they cannot.[79]

While there is a minimum level of comprehension between all Arabic dialects, this level can increase or decrease based on geographic proximity: for example, Levantine and Gulf speakers understand each other much better than they do speakers from the Maghreb. The issue of diglossia between spoken and written language is a complicating factor: A single written form, differing sharply from any of the spoken varieties learned natively, unites several sometimes divergent spoken forms. For political reasons, Arabs mostly assert that they all speak a single language, despite mutual incomprehensibility among differing spoken versions.[80]

From a linguistic standpoint, it is often said that the various spoken varieties of Arabic differ among each other collectively about as much as the Romance languages.[81] This is an apt comparison in a number of ways. The period of divergence from a single spoken form is similar—perhaps 1500 years for Arabic, 2000 years for the Romance languages. Also, while it is comprehensible to people from the Maghreb, a linguistically innovative variety such as Moroccan Arabic is essentially incomprehensible to Arabs from the Mashriq, much as French is incomprehensible to Spanish or Italian speakers but relatively easily learned by them. This suggests that the spoken varieties may linguistically be considered separate languages.[citation needed]

Status in the Arab world vis-à-vis other languages

[edit]With the sole example of medieval linguist Abu Hayyan al-Gharnati – who, while a scholar of the Arabic language, was not ethnically Arab – medieval scholars of the Arabic language made no efforts at studying comparative linguistics, considering all other languages inferior.[82]

In modern times, the educated upper classes in the Arab world have taken a nearly opposite view. Yasir Suleiman wrote in 2011 that "studying and knowing English or French in most of the Middle East and North Africa have become a badge of sophistication and modernity and ... feigning, or asserting, weakness or lack of facility in Arabic is sometimes paraded as a sign of status, class, and perversely, even education through a mélange of code-switching practises."[83]

As a foreign language

[edit]Arabic has been taught worldwide in many elementary and secondary schools, especially Muslim schools. Universities around the world have classes that teach Arabic as part of their foreign languages, Middle Eastern studies, and religious studies courses. Arabic language schools exist to assist students to learn Arabic outside the academic world. There are many Arabic language schools in the Arab world and other Muslim countries. Because the Quran is written in Arabic and all Islamic terms are in Arabic, millions[84] of Muslims (both Arab and non-Arab) study the language.

Software and books with tapes are an important part of Arabic learning, as many of Arabic learners may live in places where there are no academic or Arabic language school classes available. Radio series of Arabic language classes are also provided from some radio stations.[85] A number of websites on the Internet provide online classes for all levels as a means of distance education; most teach Modern Standard Arabic, but some teach regional varieties from numerous countries.[86]

Vocabulary

[edit]Lexicography

[edit]Pre-modern Arabic lexicography

[edit]The tradition of Arabic lexicography extended for about a millennium before the modern period.[87] Early lexicographers (لُغَوِيُّون lughawiyyūn) sought to explain words in the Quran that were unfamiliar or had a particular contextual meaning, and to identify words of non-Arabic origin that appear in the Quran.[87] They gathered shawāhid (شَوَاهِد 'instances of attested usage') from poetry and the speech of the Arabs—particularly the Bedouin ʾaʿrāb (أَعْراب) who were perceived to speak the "purest," most eloquent form of Arabic—initiating a process of jamʿu‿l-luɣah (جمع اللغة 'compiling the language') which took place over the 8th and early 9th centuries.[87]

Kitāb al-'Ayn (c. 8th century), attributed to Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi, is considered the first lexicon to include all Arabic roots; it sought to exhaust all possible root permutations—later called taqālīb (تقاليب)—calling those that are actually used mustaʿmal (مستعمَل) and those that are not used muhmal (مُهمَل).[87] Lisān al-ʿArab (1290) by Ibn Manzur gives 9,273 roots, while Tāj al-ʿArūs (1774) by Murtada az-Zabidi gives 11,978 roots.[87]

This lexicographic tradition was traditionalist and corrective in nature—holding that linguistic correctness and eloquence derive from Qurʾānic usage, pre-Islamic poetry, and Bedouin speech—positioning itself against laḥnu‿l-ʿāmmah (لَحْن العامة), the solecism it viewed as defective.[87]

Western lexicography of Arabic

[edit]In the second half of the 19th century, the British Arabist Edward William Lane, working with the Egyptian scholar Ibrāhīm Abd al-Ghaffār ad-Dasūqī,[88] compiled the Arabic–English Lexicon by translating material from earlier Arabic lexica into English.[89] The German Arabist Hans Wehr, with contributions from Hedwig Klein,[90] compiled the Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart (1952), later translated into English as A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (1961), based on established usage, especially in literature.[91]

Modern Arabic lexicography

[edit]The Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo sought to publish a historical dictionary of Arabic in the vein of the Oxford English Dictionary, tracing the changes of meanings and uses of Arabic words over time.[92] A first volume of Al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr was published in 1956 under the leadership of Taha Hussein.[93] The project is not yet complete; its 15th volume, covering the letter ṣād, was published in 2022.[94]

Loanwords

[edit]

The most important sources of borrowings into (pre-Islamic) Arabic are from the related (Semitic) languages Aramaic,[95] which used to be the principal, international language of communication throughout the ancient Near and Middle East, and Ethiopic. Many cultural, religious and political terms have entered Arabic from Iranian languages, notably Middle Persian, Parthian, and (Classical) Persian,[96] and Hellenistic Greek (kīmiyāʼ has as origin the Greek khymia, meaning in that language the melting of metals; see Roger Dachez, Histoire de la Médecine de l'Antiquité au XXe siècle, Tallandier, 2008, p. 251), alembic (distiller) from ambix (cup), almanac (climate) from almenichiakon (calendar).

For the origin of the last three borrowed words, see Alfred-Louis de Prémare, Foundations of Islam, Seuil, L'Univers Historique, 2002. Some Arabic borrowings from Semitic or Persian languages are, as presented in De Prémare's above-cited book: [citation needed]

- madīnah/medina (مدينة, city or city square), a word of Aramaic origin ܡܕ݂ܝܼܢ݇ܬܵܐ məḏī(n)ttā (in which it means "state/city").[citation needed]

- jazīrah (جزيرة), as in the well-known form الجزيرة "Al-Jazeera", means "island" and has its origin in the Syriac ܓܵܙܲܪܬܵܐ gāzartā.[citation needed]

- lāzaward (لازورد) is taken from Persian لاژورد lājvard, the name of a blue stone, lapis lazuli. This word was borrowed in several European languages to mean (light) blue – azure in English, azur in French and azul in Portuguese and Spanish.[citation needed]

A comprehensive overview of the influence of other languages on Arabic is found in Lucas & Manfredi (2020).[97]

Influence on other languages

[edit]The influence of Arabic has been most important in Islamic countries, because it is the language of the Islamic sacred book, the Quran. Arabic is also an important source of vocabulary for languages such as Amharic, Azerbaijani, Baluchi, Bengali, Berber, Bosnian, Chaldean, Chechen, Chittagonian, Croatian, Dagestani, Dhivehi, English, German, Gujarati, Hausa, Hindi, Kazakh, Kurdish, Kutchi, Kyrgyz, Malay (Malaysian and Indonesian), Pashto, Persian, Punjabi, Rohingya, Romance languages (French, Catalan, Italian, Portuguese, Sicilian, Spanish, etc.) Saraiki, Sindhi, Somali, Sylheti, Swahili, Tagalog, Tigrinya, Turkish, Turkmen, Urdu, Uyghur, Uzbek, Visayan and Wolof, as well as other languages in countries where these languages are spoken.[97] Modern Hebrew has been also influenced by Arabic especially during the process of revival, as MSA was used as a source for modern Hebrew vocabulary and roots.[98]

English has many Arabic loanwords, some directly, but most via other Mediterranean languages. Examples of such words include admiral, adobe, alchemy, alcohol, algebra, algorithm, alkaline, almanac, amber, arsenal, assassin, candy, carat, cipher, coffee, cotton, ghoul, hazard, jar, kismet, lemon, loofah, magazine, mattress, sherbet, sofa, sumac, tariff, and zenith.[99] Other languages such as Maltese[100] and Kinubi derive ultimately from Arabic, rather than merely borrowing vocabulary or grammatical rules.

Terms borrowed range from religious terminology (like Berber taẓallit, "prayer", from salat (صلاة ṣalāh)), academic terms (like Uyghur mentiq, "logic"), and economic items (like English coffee) to placeholders (like Spanish fulano, "so-and-so"), everyday terms (like Hindustani lekin, "but", or Spanish taza and French tasse, meaning "cup"), and expressions (like Catalan a betzef, "galore, in quantity"). Most Berber varieties (such as Kabyle), along with Swahili, borrow some numbers from Arabic. Most Islamic religious terms are direct borrowings from Arabic, such as صلاة (ṣalāh), "prayer", and إمام (imām), "prayer leader".[citation needed]

In languages not directly in contact with the Arab world, Arabic loanwords are often transferred indirectly via other languages rather than being transferred directly from Arabic. For example, most Arabic loanwords in Hindustani and Turkish entered through Persian. Older Arabic loanwords in Hausa were borrowed from Kanuri. Most Arabic loanwords in Yoruba entered through Hausa.[citation needed]

Arabic words made their way into several West African languages as Islam spread across the Sahara. Variants of Arabic words such as كتاب kitāb ("book") have spread to the languages of African groups who had no direct contact with Arab traders.[101]

Since, throughout the Islamic world, Arabic occupied a position similar to that of Latin in Europe, many of the Arabic concepts in the fields of science, philosophy, commerce, etc. were coined from Arabic roots by non-native Arabic speakers, notably by Aramaic and Persian translators, and then found their way into other languages. This process of using Arabic roots, especially in Kurdish and Persian, to translate foreign concepts continued through to the 18th and 19th centuries, when swaths of Arab-inhabited lands were under Ottoman rule.[citation needed]

Spoken varieties

[edit]

- 1: Hassaniyya

- 9: Saidi Arabic

- 10: Chadian Arabic

- 11: Sudanese Arabic

- 13: Najdi Arabic

- 14: Levantine Arabic

- 17: Gulf Arabic

- 18: Baharna Arabic

- 19: Hijazi Arabic

- 20: Shihhi Arabic

- 21: Omani Arabic

- 22: Dhofari Arabic

- 23: Sanaani Arabic

- 25: Hadrami Arabic

- 26: Uzbeki Arabic

- 27: Tajiki Arabic

- 28: Cypriot Arabic

- 29: Maltese

- 30: Nubi

- Sparsely populated area or no indigenous Arabic speakers

- Solid area fill: variety natively spoken by at least 25% of the population of that area or variety indigenous to that area only

- Hatched area fill: minority scattered over the area

- Dotted area fill: speakers of this variety are mixed with speakers of other Arabic varieties in the area

Colloquial Arabic is a collective term for the spoken dialects of Arabic used throughout the Arab world, which differ radically from the literary language. The main dialectal division is between the varieties within and outside of the Arabian peninsula, followed by that between sedentary varieties and the much more conservative Bedouin varieties. All the varieties outside of the Arabian peninsula, which include the large majority of speakers, have many features in common with each other that are not found in Classical Arabic. This has led researchers to postulate the existence of a prestige koine dialect in the one or two centuries immediately following the Arab conquest, whose features eventually spread to all newly conquered areas. These features are present to varying degrees inside the Arabian peninsula. Generally, the Arabian peninsula varieties have much more diversity than the non-peninsula varieties, but these have been understudied.[citation needed]

Within the non-peninsula varieties, the largest difference is between the non-Egyptian North African dialects, especially Moroccan Arabic, and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is hardly comprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Libya (although the converse is not true, in part due to the popularity of Egyptian films and other media).[citation needed]

One factor in the differentiation of the dialects is influence from the languages previously spoken in the areas, which have typically provided many new words and have sometimes also influenced pronunciation or word order. However, a more weighty factor for most dialects is, as among Romance languages, retention (or change of meaning) of different classical forms. Thus Iraqi aku, Levantine and Peninsular fīh and North African kayən all mean 'there is', and all come from Classical Arabic forms (yakūn, fīhi, kā'in respectively), but now sound very different.[citation needed]

Koiné

[edit]According to Charles A. Ferguson,[102] the following are some of the characteristic features of the koiné that underlies all the modern dialects outside the Arabian peninsula. Although many other features are common to most or all of these varieties, Ferguson believes that these features in particular are unlikely to have evolved independently more than once or twice and together suggest the existence of the koine:

- Loss of the dual number except on nouns, with consistent plural agreement (cf. feminine singular agreement in plural inanimates).

- Change of a to i in many affixes (e.g., non-past-tense prefixes ti- yi- ni-; wi- 'and'; il- 'the'; feminine -it in the construct state).

- Loss of third-weak verbs ending in w (which merge with verbs ending in y).

- Reformation of geminate verbs, e.g., ḥalaltu 'I untied' → ḥalēt(u).

- Conversion of separate words lī 'to me', laka 'to you', etc. into indirect-object clitic suffixes.

- Certain changes in the cardinal number system, e.g., khamsat ayyām 'five days' → kham(a)s tiyyām, where certain words have a special plural with prefixed t.

- Loss of the feminine elative (comparative).

- Adjective plurals of the form kibār 'big' → kubār.

- Change of nisba suffix -iyy > i.

- Certain lexical items, e.g., jāb 'bring' < jāʼa bi- 'come with'; shāf 'see'; ēsh 'what' (or similar) < ayyu shayʼ 'which thing'; illi (relative pronoun).

- Merger of /dˤ/ ⟨ض⟩ and /ðˤ/ ⟨ظ⟩ in most or all positions.

Dialect groups

[edit]- Egyptian Arabic, spoken by 67 million people in Egypt.[103] It is one of the most understood varieties of Arabic, due in large part to the widespread distribution of Egyptian films and television shows throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

- Levantine Arabic, spoken by about 44 million people in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, and Turkey.[104]

- Lebanese Arabic is a variety of Levantine Arabic spoken primarily in Lebanon.

- Jordanian Arabic is a continuum of mutually intelligible varieties of Levantine Arabic spoken by the population of the Kingdom of Jordan.

- Palestinian Arabic is a name of several dialects of the subgroup of Levantine Arabic spoken by the Palestinians in Palestine, by Arab citizens of Israel and in most Palestinian populations around the world.

- Samaritan Arabic, spoken by only several hundred in the Nablus region.

- Cypriot Maronite Arabic, spoken in Cyprus by around 9,800 people (2013 UNSD).[105]

- Maghrebi Arabic, also called "Darija", spoken by about 70 million people in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. It also forms the basis of Maltese via the extinct Sicilian Arabic dialect.[106] Maghrebi Arabic is very hard to understand for Arabic speakers from the Mashriq or Mesopotamia, the most comprehensible being Libyan Arabic and the most difficult Moroccan Arabic. The others such as Algerian Arabic can be considered in between the two in terms of difficulty.

- Libyan Arabic, spoken in Libya and neighboring countries.

- Tunisian Arabic, spoken in Tunisia and north-eastern Algeria.

- Algerian Arabic, spoken in Algeria.

- Judeo-Algerian Arabic was spoken by Jews in Algeria until 1962, now it is spoken by a few elderly Algerian Jews in France and Israel.

- Moroccan Arabic, spoken in Morocco.

- Hassaniya Arabic (3 million speakers), spoken in Mauritania, Western Sahara, some parts of the Azawad in northern Mali, southern Morocco, and south-western Algeria.

- Andalusian Arabic, spoken in Spain until the 16th century.

- Siculo-Arabic (Sicilian Arabic), was spoken in Sicily and Malta between the end of the 9th century and the end of the 12th century and eventually evolved into the Maltese language.

- Maltese, spoken on the island of Malta, is the only fully separate standardized language to have originated from an Arabic dialect, the extinct Siculo-Arabic dialect, with independent literary norms. Maltese has evolved independently of Modern Standard Arabic and its varieties into a standardized language over the past 800 years in a gradual process of Latinisation.[107][108] Maltese is therefore considered an exceptional descendant of Arabic that has no diglossic relationship with Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.[109] Maltese is different from Arabic and other Semitic languages since its morphology has been deeply influenced by Romance languages, Italian and Sicilian.[110] It is the only Semitic language written in the Latin script. In terms of basic everyday language, speakers of Maltese are reported to be able to understand less than a third of what is said to them in Tunisian Arabic,[111] which is related to Siculo-Arabic,[106] whereas speakers of Tunisian are able to understand about 40% of what is said to them in Maltese.[112] This asymmetric intelligibility is considerably lower than the mutual intelligibility found between Maghrebi Arabic dialects.[113] Maltese has its own dialects, with urban varieties of Maltese being closer to Standard Maltese than rural varieties.[114]

- Mesopotamian Arabic, spoken by about 41.2 million people in Iraq (where it is called "Aamiyah"), eastern Syria and southwestern Iran (Khuzestan) and in the southeastern of Turkey (in the eastern Mediterranean, Southeastern Anatolia Region).

- North Mesopotamian Arabic is a spoken north of the Hamrin Mountains in Iraq, in western Iran, northern Syria, and in southeastern Turkey (in the eastern Mediterranean Region, Southeastern Anatolia Region, and southern Eastern Anatolia Region).[115]

- Judeo-Mesopotamian Arabic, also known as Iraqi Judeo Arabic and Yahudic, is a variety of Arabic spoken by Iraqi Jews of Mosul.

- Baghdad Arabic is the Arabic dialect spoken in Baghdad, and the surrounding cities and it is a subvariety of Mesopotamian Arabic.

- Baghdad Jewish Arabic is the dialect spoken by the Iraqi Jews of Baghdad.

- South Mesopotamian Arabic (Basrawi dialect) is the dialect spoken in southern Iraq, such as Basra, Dhi Qar, and Najaf.[116]

- Khuzestani Arabic, spoken in the Iranian province of Khuzestan. This is a mix of Southern Mesopotamian Arabic and Gulf Arabic.

- Khorasani Arabic, spoken in the Iranian province of Khorasan.

- Kuwaiti Arabic is a Gulf Arabic dialect spoken in Kuwait.

- Sudanese Arabic, spoken by 17 million people in Sudan and some parts of southern Egypt. Sudanese Arabic is quite distinct from the dialect of its neighbor to the north; rather, the Sudanese have a dialect similar to the Hejazi dialect.

- Juba Arabic, spoken in South Sudan and southern far Sudan.

- Gulf Arabic, spoken by around four million people, predominantly in Kuwait, Bahrain, some parts of Oman, eastern Saudi Arabia coastal areas and some parts of UAE and Qatar. Also spoken in Iran's Bushehr and Hormozgan provinces. Although Gulf Arabic is spoken in Qatar, most Qatari citizens speak Najdi Arabic (Bedawi).

- Omani Arabic, distinct from the Gulf Arabic of Eastern Arabia and Bahrain, spoken in Central Oman. With its oil wealth and mobility it has spread to various areas of the former Sultanate of Muscat, especially Zanzibar and the Swahili Coast.

- Hadhrami Arabic, spoken by around 8 million people, predominantly in Hadhramaut, and in parts of the Arabian Peninsula, South and Southeast Asia, and East Africa by Hadhrami descendants.

- Indonesian Arabic, spoken in Arab ethnic enclaves in Indonesia, especially along the north coast of Java. It has about 60,000 speakers according to a rough estimate in 2010.[117]

- Yemeni Arabic, spoken in Yemen, and southern Saudi Arabia by 15 million people. Similar to Gulf Arabic.

- Najdi Arabic, spoken by around 10 million people, mainly spoken in Najd, central and northern Saudi Arabia. Most Qatari citizens speak Najdi Arabic (Bedawi).

- Hejazi Arabic (6 million speakers), spoken in Hejaz, western Saudi Arabia.

- Saharan Arabic spoken in some parts of Algeria, Niger and Mali.

- Baharna Arabic (800,000 speakers), spoken by Bahrani Shias in Bahrain and Qatif, the dialect exhibits many big differences from Gulf Arabic. It is also spoken to a lesser extent in Oman.

- Judeo-Arabic dialects – these are the dialects spoken by the Jews that had lived or continue to live in the Arab World. As Jewish migration to Israel took hold, the language did not thrive and is now considered endangered. So-called Qəltu Arabic.

- Chadian Arabic, spoken in Chad, Sudan, some parts of South Sudan, Central African Republic, Niger, Nigeria, and Cameroon.

- Central Asian Arabic, spoken in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan by around 8,000 people.[118][119] Tajiki Arabic is highly endangered.[120]

- Shirvani Arabic, spoken in Azerbaijan and Dagestan until the 1930s, now extinct.

Phonology

[edit]While many languages have numerous dialects that differ in phonology, contemporary spoken Arabic is more properly described as a continuum of varieties.[121] Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), is the standard variety shared by educated speakers throughout Arabic-speaking regions. MSA is used in writing in formal print media and orally in newscasts, speeches and formal declarations of numerous types.[122]

Modern Standard Arabic has 28 consonant phonemes and 6 vowel phonemes. The four "emphatic" (pharyngealized) consonants /sˤ, dˤ, tˤ, ðˤ/ contrast with their non-emphatic counterparts /s, d, t, ð/, other consonants including the interdentals /θ, ð/, and the pharyngeals /ħ, ʕ/ are considered rare cross-linguistically. Some of these phonemes have coalesced in the various modern dialects, while new phonemes have been introduced through borrowing or phonemic splits. A "phonemic quality of length" applies to consonants as well as vowels.[123]

Grammar

[edit]

The grammar of Arabic has similarities with the grammar of other Semitic languages. Some of the typical differences between Standard Arabic (فُصْحَى) and vernacular varieties are a loss of morphological markings of grammatical case, changes in word order, a shift toward more analytic morphosyntax, loss of grammatical mood, and loss of the inflected passive voice.

Literary Arabic

[edit]As in other Semitic languages, Arabic has a complex and unusual morphology, i.e. method of constructing words from a basic root. Arabic has a nonconcatenative "root-and-pattern" morphology: A root consists of a set of bare consonants (usually three), which are fitted into a discontinuous pattern to form words. For example, the word for 'I wrote' is constructed by combining the root k-t-b 'write' with the pattern -a-a-tu 'I Xed' to form katabtu 'I wrote'.

Other verbs meaning 'I Xed' will typically have the same pattern but with different consonants, e.g. qaraʼtu 'I read', akaltu 'I ate', dhahabtu 'I went', although other patterns are possible, e.g. sharibtu 'I drank', qultu 'I said', takallamtu 'I spoke', where the subpattern used to signal the past tense may change but the suffix -tu is always used.

From a single root k-t-b, numerous words can be formed by applying different patterns:

- كَتَبْتُ katabtu 'I wrote'

- كَتَّبْتُ kattabtu 'I had (something) written'

- كَاتَبْتُ kātabtu 'I corresponded (with someone)'

- أَكْتَبْتُ 'aktabtu 'I dictated'

- اِكْتَتَبْتُ iktatabtu 'I subscribed'

- تَكَاتَبْنَا takātabnā 'we corresponded with each other'

- أَكْتُبُ 'aktubu 'I write'

- أُكَتِّبُ 'ukattibu 'I have (something) written'

- أُكَاتِبُ 'ukātibu 'I correspond (with someone)'

- أُكْتِبُ 'uktibu 'I dictate'

- أَكْتَتِبُ 'aktatibu 'I subscribe'

- نَتَكَتِبُ natakātabu 'we correspond each other'

- كُتِبَ kutiba 'it was written'

- أُكْتِبَ 'uktiba 'it was dictated'

- مَكْتُوبٌ maktūbun 'written'

- مُكْتَبٌ muktabun 'dictated'

- كِتَابٌ kitābun 'book'

- كُتُبٌ kutubun 'books'

- كَاتِبٌ kātibun 'writer'

- كُتَّابٌ kuttābun 'writers'

- مَكْتَبٌ maktabun 'desk, office'

- مَكْتَبَةٌ maktabatun 'library, bookshop'

- etc.

Nouns and adjectives

[edit]Nouns in Literary Arabic have three grammatical cases (nominative, accusative, and genitive [also used when the noun is governed by a preposition]); three numbers (singular, dual and plural); two genders (masculine and feminine); and three "states" (indefinite, definite, and construct). The cases of singular nouns, other than those that end in long ā, are indicated by suffixed short vowels (/-u/ for nominative, /-a/ for accusative, /-i/ for genitive).

The feminine singular is often marked by ـَة /-at/, which is pronounced as /-ah/ before a pause. Plural is indicated either through endings (the sound plural) or internal modification (the broken plural). Definite nouns include all proper nouns, all nouns in "construct state" and all nouns which are prefixed by the definite article اَلْـ /al-/. Indefinite singular nouns, other than those that end in long ā, add a final /-n/ to the case-marking vowels, giving /-un/, /-an/ or /-in/, which is also referred to as nunation or tanwīn.

Adjectives in Literary Arabic are marked for case, number, gender and state, as for nouns. The plural of all non-human nouns is always combined with a singular feminine adjective, which takes the ـَة /-at/ suffix.

Pronouns in Literary Arabic are marked for person, number and gender. There are two varieties, independent pronouns and enclitics. Enclitic pronouns are attached to the end of a verb, noun or preposition and indicate verbal and prepositional objects or possession of nouns. The first-person singular pronoun has a different enclitic form used for verbs (ـنِي /-nī/) and for nouns or prepositions (ـِي /-ī/ after consonants, ـيَ /-ya/ after vowels).

Nouns, verbs, pronouns and adjectives agree with each other in all respects. Non-human plural nouns are grammatically considered to be feminine singular. A verb in a verb-initial sentence is marked as singular regardless of its semantic number when the subject of the verb is explicitly mentioned as a noun. Numerals between three and ten show "chiasmic" agreement, in that grammatically masculine numerals have feminine marking and vice versa.

Verbs

[edit]Verbs in Literary Arabic are marked for person (first, second, or third), gender, and number. They are conjugated in two major paradigms (past and non-past); two voices (active and passive); and six moods (indicative, imperative, subjunctive, jussive, shorter energetic and longer energetic); the fifth and sixth moods, the energetics, exist only in Classical Arabic but not in MSA.[124] There are two participles, active and passive, and a verbal noun, but no infinitive.

The past and non-past paradigms are sometimes termed perfective and imperfective, indicating the fact that they actually represent a combination of tense and aspect. The moods other than the indicative occur only in the non-past, and the future tense is signaled by prefixing سَـ sa- or سَوْفَ sawfa onto the non-past. The past and non-past differ in the form of the stem (e.g., past كَتَبـ katab- vs. non-past ـكْتُبـ -ktub-), and use completely different sets of affixes for indicating person, number and gender: In the past, the person, number and gender are fused into a single suffixal morpheme, while in the non-past, a combination of prefixes (primarily encoding person) and suffixes (primarily encoding gender and number) are used. The passive voice uses the same person/number/gender affixes but changes the vowels of the stem.

The following shows a paradigm of a regular Arabic verb, كَتَبَ kataba 'to write'. In Modern Standard, the energetic mood, in either long or short form, which has the same meaning, is almost never used.

Derivation

[edit]Like other Semitic languages, and unlike most other languages, Arabic makes much more use of nonconcatenative morphology, applying many templates applied to roots, to derive words than adding prefixes or suffixes to words.

For verbs, a given root can occur in many different derived verb stems, of which there are about fifteen, each with one or more characteristic meanings and each with its own templates for the past and non-past stems, active and passive participles, and verbal noun. These are referred to by Western scholars as "Form I", "Form II", and so on through "Form XV", although Forms XI to XV are rare.

These stems encode grammatical functions such as the causative, intensive and reflexive. Stems sharing the same root consonants represent separate verbs, albeit often semantically related, and each is the basis for its own conjugational paradigm. As a result, these derived stems are part of the system of derivational morphology, not part of the inflectional system.

Examples of the different verbs formed from the root كتب k-t-b 'write' (using حمر ḥ-m-r 'red' for Form IX, which is limited to colors and physical defects):

| Form | Past | Meaning | Non-past | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | kataba | 'he wrote' | yaktubu | 'he writes' |

| II | kattaba | 'he made (someone) write' | yukattibu | "he makes (someone) write" |

| III | kātaba | 'he corresponded with, wrote to (someone)' | yukātibu | 'he corresponds with, writes to (someone)' |

| IV | ʾaktaba | 'he dictated' | yuktibu | 'he dictates' |

| V | takattaba | nonexistent | yatakattabu | nonexistent |

| VI | takātaba | 'he corresponded (with someone, esp. mutually)' | yatakātabu | 'he corresponds (with someone, esp. mutually)' |

| VII | inkataba | 'he subscribed' | yankatibu | 'he subscribes' |

| VIII | iktataba | 'he copied' | yaktatibu | 'he copies' |

| IX | iḥmarra | 'he turned red' | yaḥmarru | 'he turns red' |

| X | istaktaba | 'he asked (someone) to write' | yastaktibu | 'he asks (someone) to write' |

Form II is sometimes used to create transitive denominative verbs (verbs built from nouns); Form V is the equivalent used for intransitive denominatives.

The associated participles and verbal nouns of a verb are the primary means of forming new lexical nouns in Arabic. This is similar to the process by which, for example, the English gerund "meeting" (similar to a verbal noun) has turned into a noun referring to a particular type of social, often work-related event where people gather together to have a "discussion" (another lexicalized verbal noun). Another fairly common means of forming nouns is through one of a limited number of patterns that can be applied directly to roots, such as the "nouns of location" in ma- (e.g. maktab 'desk, office' < k-t-b 'write', maṭbakh 'kitchen' < ṭ-b-kh 'cook').

The only three genuine suffixes are as follows:

- The feminine suffix -ah; variously derives terms for women from related terms for men, or more generally terms along the same lines as the corresponding masculine, e.g. maktabah 'library' (also a writing-related place, but different from maktab, as above).

- The nisbah suffix -iyy-. This suffix is extremely productive, and forms adjectives meaning "related to X". It corresponds to English adjectives in -ic, -al, -an, -y, -ist, etc.

- The feminine nisbah suffix -iyyah. This is formed by adding the feminine suffix -ah onto nisba adjectives to form abstract nouns. For example, from the basic root š-r-k 'share' can be derived the Form VIII verb ishtaraka 'to cooperate, participate', and in turn its verbal noun ištirāk 'cooperation, participation' can be formed. This in turn can be made into a nisbah adjective ištirākiyy 'socialist', from which an abstract noun ishtirākiyyah 'socialism' can be derived. Other recent formations are jumhūriyyah 'republic' (lit. "public-ness", < jumhūr 'multitude, general public'), and the Gaddafi-specific variation jamāhīriyyah 'people's republic' (lit. "masses-ness", < jamāhīr 'the masses', pl. of jumhūr, as above).

Colloquial varieties

[edit]The spoken dialects have lost the case distinctions and make only limited use of the dual (it occurs only on nouns and its use is no longer required in all circumstances). They have lost the mood distinctions other than imperative, but many have since gained new moods through the use of prefixes (most often /bi-/ for indicative vs. unmarked subjunctive). They have also mostly lost the indefinite "nunation" and the internal passive.

The following is an example of a regular verb paradigm in Egyptian Arabic.

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | ||||||

| 1st | katáb-t | á-ktib | bá-ktib | ḥá-ktib | " | |

| 2nd | masculine | katáb-t | tí-ktib | bi-tí-ktib | ḥa-tí-ktib | í-ktib |

| feminine | katáb-ti | ti-ktíb-i | bi-ti-ktíb-i | ḥa-ti-ktíb-i | i-ktíb-i | |

| 3rd | masculine | kátab | yí-ktib | bi-yí-ktib | ḥa-yí-ktib | " |

| feminine | kátab-it | tí-ktib | bi-tí-ktib | ḥa-tí-ktib | ||

| Plural | ||||||

| 1st | katáb-na | ní-ktib | bi-ní-ktib | ḥá-ní-ktib | " | |

| 2nd | katáb-tu | ti-ktíb-u | bi-ti-ktíb-u | ḥa-ti-ktíb-u | i-ktíb-u | |

| 3rd | kátab-u | yi-ktíb-u | bi-yi-ktíb-u | ḥa-yi-ktíb-u | " | |

Writing system

[edit]

The Arabic alphabet derives from the Aramaic through Nabatean, to which it bears a loose resemblance like that of Coptic or Cyrillic scripts to Greek script. Traditionally, there were several differences between the Western (North African) and Middle Eastern versions of the alphabet—in particular, the faʼ had a dot underneath and qaf a single dot above in the Maghreb, and the order of the letters was slightly different (at least when they were used as numerals).

However, the old Maghrebi variant has been abandoned except for calligraphic purposes in the Maghreb itself, and remains in use mainly in the Quranic schools (zaouias) of West Africa. Arabic, like all other Semitic languages (except for the Latin-written Maltese, and the languages with the Ge'ez script), is written from right to left. There are several styles of scripts such as thuluth, muhaqqaq, tawqi, rayhan, and notably naskh, which is used in print and by computers, and ruqʻah, which is commonly used for correspondence.[125][126]

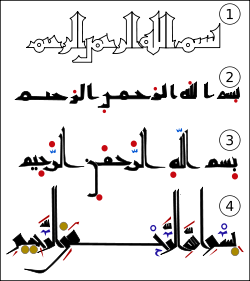

Originally Arabic was made up of only rasm without diacritical marks[127] Later diacritical points (which in Arabic are referred to as nuqaṯ) were added (which allowed readers to distinguish between letters such as b, t, th, n and y). Finally signs known as Tashkil were used for short vowels known as harakat and other uses such as final postnasalized or long vowels.

| Arabic Alphabet | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wikipedia

Romanization |

Value in MSA

(IPA) |

Contextual forms | Isolated form | No. | ||

| Final | Medial | Initial | ||||

| ā | /aː/ | ـا | ا | 1 | ||

| b | /b/ | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب | 2 |

| t | /t/ | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت | 3 |

| ṯ or th | /θ/ | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث | 4 |

| j | /d͡ʒ/* | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج | 5 |

| ḥ | /ħ/ | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح | 6 |

| ḵ or kh | /x/ | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ | 7 |

| d | /d/ | ـد | د | 8 | ||

| ḏ or dh | /ð/ | ـذ | ذ | 9 | ||

| r | /r/ | ـر | ر | 10 | ||

| z | /z/ | ـز | ز | 11 | ||

| s | /s/ | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س | 12 |

| š or sh | /ʃ/ | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش | 13 |

| ṣ | /sˤ/ | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص | 14 |

| ḍ | /dˤ/ | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض | 15 |

| ṭ | /tˤ/ | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط | 16 |

| ẓ | /ðˤ/ | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ | 17 |

| ʻ or ʕ | /ʕ/ | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع | 18 |

| ḡ or gh | /ɣ/ | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ | 19 |

| f | /f/ | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف | 20 |

| q | /q/ | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق | 21 |

| k | /k/ | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | ك | 22 |

| l | /l/ | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل | 23 |

| m | /m/ | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م | 24 |

| n | /n/ | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن | 25 |

| h | /h/ | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ﻩ | 26 |

| w and ū | /w/, /uː/ | ـو | و | 27 | ||

| y and ī | /j/, /iː/ | ـي | ـيـ | يـ | ي | 28 |

| ʾ or ʔ | /ʔ/ | ء | - | |||

Notes:

- Modern Standard Arabic (Literary Arabic) ⟨ج⟩ can be pronounced /d͡ʒ/ or /ʒ/ (or /g/ only in Egypt) depending on the speaker's regional dialect.

- The Hamza ⟨ء⟩ can be considered a letter and plays an important role in Arabic spelling but it is not considered part of the alphabet, it has different written forms depending on its position in the word, check Hamza.

Calligraphy

[edit]After Khalil ibn Ahmad al Farahidi finally fixed the Arabic script around 786, many styles were developed, both for the writing down of the Quran and other books, and for inscriptions on monuments as decoration.

Arabic calligraphy has not fallen out of use as calligraphy has in the Western world, and is still considered by Arabs as a major art form; calligraphers are held in great esteem. Being cursive by nature, unlike the Latin script, Arabic script is used to write down a verse of the Quran, a hadith, or a proverb. The composition is often abstract, but sometimes the writing is shaped into an actual form such as that of an animal. One of the current masters of the genre is Hassan Massoudy.[128]

In modern times the intrinsically calligraphic nature of the written Arabic form is haunted by the thought that a typographic approach to the language, necessary for digitized unification, will not always accurately maintain meanings conveyed through calligraphy.[129]

Romanization

[edit]There are a number of different standards for the romanization of Arabic, i.e. methods of accurately and efficiently representing Arabic with the Latin script. There are various conflicting motivations involved, which leads to multiple systems. Some are interested in transliteration, i.e. representing the spelling of Arabic, while others focus on transcription, i.e. representing the pronunciation of Arabic. (They differ in that, for example, the same letter ي is used to represent both a consonant, as in "you" or "yet", and a vowel, as in "me" or "eat".)

Some systems, e.g. for scholarly use, are intended to accurately and unambiguously represent the phonemes of Arabic, generally making the phonetics more explicit than the original word in the Arabic script. These systems are heavily reliant on diacritical marks such as "š" for the sound equivalently written sh in English. Other systems (e.g. the Bahá'í orthography) are intended to help readers who are neither Arabic speakers nor linguists with intuitive pronunciation of Arabic names and phrases.[citation needed]

These less "scientific" systems tend to avoid diacritics and use digraphs (like sh and kh). These are usually simpler to read, but sacrifice the definiteness of the scientific systems, and may lead to ambiguities, e.g. whether to interpret sh as a single sound, as in gash, or a combination of two sounds, as in gashouse. The ALA-LC romanization solves this problem by separating the two sounds with a prime symbol ( ′ ); e.g., as′hal 'easier'.

During the last few decades and especially since the 1990s, Western-invented text communication technologies have become prevalent in the Arab world, such as personal computers, the World Wide Web, email, bulletin board systems, IRC, instant messaging and mobile phone text messaging. Most of these technologies originally had the ability to communicate using the Latin script only, and some of them still do not have the Arabic script as an optional feature. As a result, Arabic speaking users communicated in these technologies by transliterating the Arabic text using the Latin script.

To handle those Arabic letters that cannot be accurately represented using the Latin script, numerals and other characters were appropriated. For example, the numeral "3" may be used to represent the Arabic letter ⟨ع⟩. There is no universal name for this type of transliteration, but some have named it Arabic Chat Alphabet or IM Arabic. Other systems of transliteration exist, such as using dots or capitalization to represent the "emphatic" counterparts of certain consonants. For instance, using capitalization, the letter ⟨د⟩, may be represented by d. Its emphatic counterpart, ⟨ض⟩, may be written as D.

Numerals

[edit]In most of present-day North Africa, the Western Arabic numerals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) are used. However, in Egypt and Arabic-speaking countries to the east of it, the Eastern Arabic numerals (٠ – ١ – ٢ – ٣ – ٤ – ٥ – ٦ – ٧ – ٨ – ٩) are in use. When representing a number in Arabic, the lowest-valued position is placed on the right, so the order of positions is the same as in left-to-right scripts. Sequences of digits such as telephone numbers are read from left to right, but numbers are spoken in the traditional Arabic fashion, with units and tens reversed from the modern English usage. For example, 24 is said "four and twenty" just like in the German language (vierundzwanzig) and Classical Hebrew, and 1975 is said "a thousand and nine-hundred and five and seventy" or, more eloquently, "a thousand and nine-hundred five seventy".

Arabic alphabet and nationalism

[edit]There have been many instances of national movements to convert Arabic script into Latin script or to Romanize the language. Currently, the only Arabic variety to use Latin script is Maltese.

Lebanon

[edit]The Beirut newspaper La Syrie pushed for the change from Arabic script to Latin letters in 1922. The major head of this movement was Louis Massignon, a French Orientalist, who brought his concern before the Arabic Language Academy in Damascus in 1928. Massignon's attempt at Romanization failed as the academy and population viewed the proposal as an attempt from the Western world to take over their country. Sa'id Afghani, a member of the academy, mentioned that the movement to Romanize the script was a Zionist plan to dominate Lebanon.[130][131] Said Akl created a Latin-based alphabet for Lebanese and used it in a newspaper he founded, Lebnaan, as well as in some books he wrote.

Egypt

[edit]After the period of colonialism in Egypt, Egyptians were looking for a way to reclaim and re-emphasize Egyptian culture. As a result, some Egyptians pushed for an Egyptianization of the Arabic language in which the formal Arabic and the colloquial Arabic would be combined into one language and the Latin alphabet would be used.[130][131] There was also the idea of finding a way to use Hieroglyphics instead of the Latin alphabet, but this was seen as too complicated to use.[130][131]

A scholar, Salama Musa agreed with the idea of applying a Latin alphabet to Arabic, as he believed that would allow Egypt to have a closer relationship with the West. He also believed that Latin script was key to the success of Egypt as it would allow for more advances in science and technology. This change in alphabet, he believed, would solve the problems inherent with Arabic, such as a lack of written vowels and difficulties writing foreign words that made it difficult for non-native speakers to learn.[130][131] Ahmad Lutfi As Sayid and Muhammad Azmi, two Egyptian intellectuals, agreed with Musa and supported the push for Romanization.[130][132]

The idea that Romanization was necessary for modernization and growth in Egypt continued with Abd Al-Aziz Fahmi in 1944. He was the chairman for the Writing and Grammar Committee for the Arabic Language Academy of Cairo.[130][132] This effort failed as the Egyptian people felt a strong cultural tie to the Arabic alphabet.[130][132] In particular, the older Egyptian generations believed that the Arabic alphabet had strong connections to Arab values and history, due to the long history of the Arabic alphabet (Shrivtiel, 189) in Muslim societies.

Sample text

[edit]| Modern Standard Arabic, Arabic script[133] | ALA-LC transliteration | English[134] |

|---|---|---|

يولد جميع الناس أحراراً متساوين في الكرامة والحقوق، وقد وهبوا عقلاً وضميراً وعليهم أن يعامل بعضهم بعضاً بروح الإخاء.

|

Yūlad jamīʻ al-nās aḥrār-an mutasāwīn fil-karāma-ti wal-huqūq-i, wa-qad wuhibū ʻaql-an wa-ḍamīr-an wa-ʻalayhim an yuʻāmil-u baʻduhum baʻd-an bi-rūh al-ikhāʼ-i. | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

See also

[edit]- Arabic Ontology

- Arabic diglossia

- Arabic language influence on the Spanish language

- Arabic Language International Council

- Arabic literature

- Arabic–English Lexicon

- Arabist

- A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic

- Glossary of Islam

- International Association of Arabic Dialectology

- List of Arab newspapers

- List of Arabic-language television channels

- List of Arabic given names

- List of countries where Arabic is an official language

- Arabic-based creole languages

- Varieties of Arabic

- List of French words of Arabic origin

- Replacement of loanwords in Turkish

Notes

[edit]- ^ The constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran recognizes the Arabic language as the language of Islam, giving it a formal status as the language of religion, and regulates its spreading within the Iranian national curriculum. The constitution declares in Chapter II: (The Official Language, Script, Calendar, and Flag of the Country) in Article 16 "Since the language of the Qur`an and Islamic texts and teachings is Arabic, ..., it must be taught after elementary level, in all classes of secondary school and in all areas of study."[4]

- ^ The constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan states in Article 31 No. 2 that "The State shall endeavour, as respects the Muslims of Pakistan (a) to make the teaching of the Holy Quran and Islamiat compulsory, to encourage and facilitate the learning of Arabic language ..."[5]

- ^ endonym: اَلْعَرَبِيَّةُ, romanized: al-ʿarabiyyah, pronounced [al ʕaraˈbijːa] ⓘ, or عَرَبِيّ, ʿarabīy, pronounced [ˈʕarabiː] ⓘ or [ʕaraˈbij]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Arabic at Ethnologue (28th ed., 2025)

- ^ Arabic at Ethnologue (28th ed., 2025)

- ^ "Eritrea", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 26 April 2023, retrieved 29 April 2023

- ^ Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran: Iran (Islamic Republic of)'s Constitution of 1979. – Article: 16 Official or national languages, 1979, retrieved 25 July 2018

- ^ Constitution of Pakistan: Constitution of Pakistan, 1973 – Article: 31 Islamic way of life, 1973, retrieved 13 June 2018

- ^ "Implementation of the Charter in Cyprus". Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People" (PDF). Knesset. 19 July 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "Mali". www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Niger : Loi n° 2001-037 du 31 décembre 2001 fixant les modalités de promotion et de développement des langues nationales". www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca (in French). Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Constitution of the Philippines, Article XIV, Sec 7: For purposes of communication and instruction, the official languages of the Philippines are Filipino and, until otherwise provided by law, English. The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein. Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.

- ^ a b "Decret n° 2005-980 du 21 octobre 2005". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (PDF) (2013 English version ed.). Constitutional Court of South Africa. 2013. ch. 1, s. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Al-Jallad, Ahmad (16 November 2015). "Al-Jallad. The earliest stages of Arabic and its linguistic classification". Routledge Handbook of Arabic Linguistics, forthcoming. p. 315. ISBN 9781315147062. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: ara". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2017). "The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity?" (PDF). Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. 11 (2): 117–145. doi:10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006. hdl:10023/12443. ISSN 2570-5857. S2CID 158624482. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Wright (2001:492)

- ^ a b "What are the official languages of the United Nations? - Ask DAG!". ask.un.org. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b World, I. H. "Arabic". IH World. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Maltese language". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Versteegh, Kees; Versteegh, C. H. M. (1997). The Arabic Language. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231111522.

... of the Qufdn; many Arabic loanwords in the indigenous languages, as in Urdu and Indonesian, were introduced mainly through the medium of Persian.

- ^ Bhabani Charan Ray (1981). "Appendix B Persian, Turkish, Arabic words generally used in Oriya". Orissa Under the Mughals: From Akbar to Alivardi : a Fascinating Study of the Socio-economic and Cultural History of Orissa. Orissan studies project, 10. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak. p. 213. OCLC 461886299.

- ^ Lane, James (2 June 2021). "The 10 Most Spoken Languages In The World". Babbel. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "Internet: most common languages online 2020". Statista. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Top Ten Internet Languages in The World - Internet Statistics". www.internetworldstats.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Mandarin Chinese Most Useful Business Language After English - Bloomberg Business". Bloomberg News. 29 March 2015. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Versteegh, Cornelis Henricus Maria "Kees" (1997). The Arabic Language. Columbia University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-231-11152-2.

- ^ a b c d Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin/Boston, 2011.

- ^ a b Al-Jallad 2020a, p. 8.

- ^ Huehnergard, John (2017). "Arabic in Its Semitic Context". In Al-Jallad, Ahmad (ed.). Arabic in Context: Celebrating 400 Years of Arabic at Leiden University. Brill. p. 13. doi:10.1163/9789004343047_002. ISBN 978-90-04-34304-7. OCLC 967854618.

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2015). An Outline of the Grammar of the Safaitic Inscriptions. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-28982-6. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Birnstiel 2019, p. 368.

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2021). "Connecting the Lines between Old (Epigraphic) Arabic and the Modern Vernaculars". Languages. 6 (4): 1. doi:10.3390/languages6040173. ISSN 2226-471X.

- ^ Versteegh 2014, p. 172.

- ^ Macdonald, Michael C. A. "Arabians, Arabias, and the Greeks_Contact and Perceptions". Literacy and Identity in Pre-Islamic Arabia. pp. 15–17. ISBN 9781003278818. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (January 2014). "Al-Jallad. 2014. On the genetic background of the Rbbl bn Hfʿm grave inscription at Qaryat al-Fāw". BSOAS. 77 (3): 445–465. doi:10.1017/S0041977X14000524.

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad. "Al-Jallad (Draft) Remarks on the classification of the languages of North Arabia in the 2nd edition of The Semitic Languages (eds. J. Huehnergard and N. Pat-El)".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad. "One wāw to rule them all: the origins and fate of wawation in Arabic and its orthography".

- ^ Nehmé, Laila (January 2010). ""A glimpse of the development of the Nabataean script into Arabic based on old and new epigraphic material", in M.C.A. Macdonald (ed), The development of Arabic as a written language (Supplement to the Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 40). Oxford: 47–88". Supplement to the Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies.

- ^ Lentin, Jérôme (30 May 2011). "Middle Arabic". Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill Reference. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Team, Almaany. "ترجمة و معنى نحو بالإنجليزي في قاموس المعاني. قاموس عربي انجليزي مصطلحات صفحة 1". www.almaany.com. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Leaman, Oliver (2006). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-32639-1.