Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

English language

View on Wikipedia

| English | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɪŋɡlɪʃ/ ING-lish[1] |

| Native to | The English-speaking world, including the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Commonwealth Caribbean, South Africa and others |

| Speakers | L1: 380 million (2021)[2] |

| Dialects | (full list) |

| |

| Manually coded English (multiple systems) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | en |

| ISO 639-2 | eng |

| ISO 639-3 | eng |

| Glottolog | stan1293 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABA |

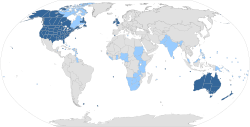

Regions where English is the native language of the majority

Regions where English is an official or widely spoken language, but not a majority native language | |

English is a West Germanic language that emerged in early medieval England and has since become a global lingua franca.[4][5][6] The namesake of the language is the Angles, one of the Germanic peoples who migrated to Britain after the end of Roman rule. English is the most spoken language in the world, primarily due to the global influences of the former British Empire (succeeded by the Commonwealth of Nations) and the United States. It is the most widely learned second language in the world, with more second-language speakers than native speakers. However, English is only the third-most spoken native language, after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish.[3]

English is either the official language, or one of the official languages, in 57 sovereign states and 30 dependent territories, making it the most geographically widespread language in the world. In the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, it is the dominant language for historical reasons without being explicitly defined by law.[7] It is a co-official language of the United Nations, the European Union, and many other international and regional organisations. It has also become the de facto lingua franca of diplomacy, science, technology, international trade, logistics, tourism, aviation, entertainment, and the Internet.[8] Ethnologue estimated that there were over 1.4 billion speakers worldwide as of 2021[update].[3]

Old English emerged from a group of West Germanic dialects spoken by the Anglo-Saxons, and written with a runic system (the futhorc), although the transition to a Latin-based script began early on. Late Old English borrowed some grammar and core vocabulary from Old Norse, a North Germanic language.[9][10][11] Then, Middle English borrowed vocabulary extensively from French dialects, which are the source of approximately 28 percent of Modern English words, and from Latin, which is the source of an additional 28 percent.[12] While Latin and the Romance languages are thus the source for a majority of its lexicon taken as a whole, English grammar and phonology retain a family resemblance with the Germanic languages, and most of its basic everyday vocabulary remains Germanic in origin. English exists on a dialect continuum with Scots; it is next-most closely related to Low Saxon and Frisian.

Classification

[edit]English is a member of the Indo-European language family, belonging to the West Germanic branch of Germanic languages.[13] Owing to their descent from a shared ancestor language known as Proto-Germanic, English and other Germanic languages – which include Dutch, German, and Swedish[14] – have characteristic features in common, including a division of verbs into strong and weak classes, the use of modal verbs, and sound changes affecting Proto-Indo-European consonants known as Grimm's and Verner's laws.[15]

Old English was one of several Ingvaeonic languages, which emerged from a dialect continuum spoken by West Germanic peoples during the 5th century in Frisia, on the coast of the North Sea. Old English emerged among the Ingvaeonic speakers on the British Isles following their migration there, while the other Ingvaeonic languages (Frisian and Old Low German) developed in parallel on the continent.[16] Old English evolved into Middle English, which in turn evolved into Modern English.[17] Particular dialects of Old and Middle English also developed into other Anglic languages, including Scots[18] and the extinct Fingallian and Yola dialects of Ireland.[19]

English was isolated from other Germanic languages on the continent and diverged considerably in vocabulary, syntax, and phonology as a result. It is not mutually intelligible with any continental Germanic language – though some, such as Dutch and Frisian, show strong affinities with it, especially in its earlier stages.[20][page needed] English and Frisian were traditionally considered more closely related to one another than they were to other West Germanic languages, but most modern scholarship does not recognise a particular affinity between them.[21] Though they exhibited similar sound changes not otherwise found around the North Sea at that time, the specific changes appeared in English and Frisian at different times – a pattern uncharacteristic for languages sharing a unique phylogenetic ancestor.[22][23]

History

[edit]Proto-Germanic to Old English

[edit]

[Listen! We have heard of the glory in bygone days of the folk-kings of the spear-Danes ...][24]

Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon) was the earliest form of the English language, spoken from c. 450 to c. 1150. Old English developed from a set of West Germanic dialects, sometimes identified as Anglo-Frisian or North Sea Germanic, that were originally spoken along the coasts of Frisia, Lower Saxony and southern Jutland by Germanic peoples known to the historical record as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.[25] From the 5th century, the Anglo-Saxons settled Britain as the Roman economy and administration collapsed. By the 7th century, Old English had become dominant in Britain – replacing the Common Brittonic and British Latin previously spoken during the Roman occupation,[26][27][28] which ultimately left little influence on English. England and English (originally Ænglaland and Ænglisc) are both named after the Angles.[29]

Old English was divided into two Anglian dialects (Mercian and Northumbrian) and two Saxon dialects (Kentish and West Saxon).[30] Through the influence exerted by the kingdom of Wessex, and the educational reforms instated by King Alfred during the 9th century, the West Saxon dialect became the standard written variety.[31] The epic poem Beowulf is written in West Saxon, and the earliest English poem, Cædmon's Hymn, is written in Northumbrian.[32] Modern English developed mainly from Mercian, but the Scots language developed from Northumbrian. During the earliest period of Old English, a few short inscriptions were made using a runic alphabet.[33] By the 6th century, a Latin alphabet had been adopted. Written with half-uncial letterforms, it included the runic letters wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨þ⟩, and the modified Latin letters eth ⟨ð⟩, and ash ⟨æ⟩.[33][34]

Old English is a markedly different from Modern English, such that 21st-century English speakers are entirely unable to understand Old English without special training. Its grammar was similar to that of modern German: nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs had many more inflectional endings and forms, and word order was much freer than in Modern English. Modern English has case forms in pronouns (he, him, his) and has a few verb inflections (speak, speaks, speaking, spoke, spoken), but Old English had case endings in nouns as well, and verbs had more person and number endings.[35][36][37]

Influence of Old Norse

[edit]Between the 8th and 11th centuries, the English spoken in some regions underwent significant changes due to contact with Old Norse, a North Germanic language. Several waves of Norsemen colonising the northern British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries put Old English speakers in constant contact with Old Norse. Norse influence was strongest in the north-eastern varieties of Old English spoken in the Danelaw surrounding York; today these features are still particularly present in Scots and Northern English. The centre of Norse influence was Lindsey, located in the Midlands. After Lindsey was incorporated into the Anglo-Saxon polity in 920, English spread extensively throughout the region. An element of Norse influence that continues in all English varieties today is the third person pronoun group beginning with th- (they, them, their) which replaced the Anglo-Saxon pronouns with h- (hie, him, hera).[38]

Other Norse loanwords include give, get, sky, skirt, egg, and cake, typically displacing a native Anglo-Saxon equivalent. Old Norse in this era retained considerable mutual intelligibility with some dialects of Old English, particularly northern ones.[39]

Middle English

[edit]Englischmen þeyz hy hadde fram þe bygynnyng þre manner speche, Souþeron, Northeron, and Myddel speche in þe myddel of þe lond, ... Noþeles by comyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes, and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys asperyed, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbytting.

[Although, from the beginning, Englishmen had three manners of speaking, southern, northern and midlands speech in the middle of the country, ... Nevertheless, through intermingling and mixing, first with Danes and then with Normans, amongst many the country language has arisen, and some use strange stammering, chattering, snarling, and grating gnashing.]

The Middle English period is often defined as beginning with the Norman Conquest in 1066. During the centuries that followed, English was heavily influenced by the form of Old French spoken by the new Norman ruling class that had migrated to England (known as Old Norman). Over the following decades of contact, members of the middle and upper classes, whether native English or Norman, became increasingly bilingual. By 1150 at the latest, bilingual speakers represented a majority of the English aristocracy, and monolingual French speakers were nearly non-existent.[41] The French spoken by the Norman elite in England eventually developed into the Anglo-Norman language.[42] The division between Old to Middle English can also be placed during the composition of the Ormulum (c. late 12th century), a work by the Augustinian canon Orrm which highlights blending of Old English and Anglo-Norman elements in the language for the first time.[43][44]

As the lower classes, who represented the vast majority of the population, remained monolingual English speakers, a primary influence of Norman was as a lexical superstratum, introducing a wide range of loanwords related to politics, legislation and prestigious social domains.[11] For instance, the French word trône appears for the first time, from which the English word throne is derived.[45] Middle English also greatly simplified the inflectional system, probably in order to reconcile Old Norse and Old English, which were inflectionally different but morphologically similar. The distinction between nominative and accusative cases was lost except in personal pronouns, the instrumental case was dropped, and the use of the genitive case was limited to indicating possession. The inflectional system regularised many irregular inflectional forms,[46] and gradually simplified the system of agreement, making word order less flexible.[47]

Middle English literature includes Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (c. 1400), and Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (1485). In the Middle English period, the use of regional dialects in writing proliferated, and dialect traits were even used for effect by authors such as Chaucer.[48] In the first translation of the entire Bible into English by John Wycliffe (1382), Matthew 8:20 reads: "Foxis han dennes, and briddis of heuene han nestis."[49] Here the plural suffix -n on the verb have is still retained, but none of the case endings on the nouns are present.

Early Modern English

[edit]

The period of Early Modern English, lasting between 1500 and 1700, was characterised by the Great Vowel Shift (1350–1700), inflectional simplification, and linguistic standardisation. The Great Vowel Shift affected the stressed long vowels of Middle English. It was a chain shift, meaning that each shift triggered a subsequent shift in the vowel system. Mid and open vowels were raised, and close vowels were broken into diphthongs. For example, the word bite was originally pronounced as the word beet is today, and the second vowel in the word about was pronounced as the word boot is today. The Great Vowel Shift explains many irregularities in spelling since English retains many spellings from Middle English, and it also explains why English vowel letters have very different pronunciations from the same letters in other languages.[50][51]

English began to rise in prestige, relative to Norman French, during the reign of Henry V. Around 1430, the Court of Chancery in Westminster began using English in its official documents, and a new standard form of Middle English, known as Chancery Standard, developed from the dialects of London and the East Midlands. In 1476, William Caxton introduced the printing press to England and began publishing the first printed books in London, expanding the influence of this form of English.[52]

Literature in Early Modern English includes the works of William Shakespeare and the 1611 King James Version (KJV) of the Bible. Even after the vowel shift the language still sounded different from Modern English: for example, the consonant clusters /kn ɡn sw/ in knight, gnat, and sword were still pronounced. Many of the grammatical features that a modern reader of Shakespeare might find quaint or archaic represent the distinct characteristics of Early Modern English.[53] Matthew 8:20 in the KJV reads: "The Foxes have holes and the birds of the ayre have nests."[54] This exemplifies the loss of case and its effects on sentence structure (replacement with subject–verb–object word order, and the use of of instead of the non-possessive genitive), and the introduction of loanwords from French (ayre) and word replacements (bird, originally meaning 'nestling', which had replaced Old English fugol).[54]

Spread of Modern English

[edit]By the late 18th century, the British Empire had spread English through its colonies and geopolitical dominance. Commerce, science and technology, diplomacy, art, and formal education all contributed to English becoming the first truly global language. English also facilitated worldwide international communication.[55][4] English was adopted in parts of North America, parts of Africa, Oceania, and many other regions. When they obtained political independence, some of the newly independent states that had multiple indigenous languages opted to continue using English as the official language to avoid the political and other difficulties inherent in promoting any one indigenous language above the others.[56][57][58] In the 20th century the growing economic and cultural influence of the United States and its status as a superpower following the Second World War has, along with worldwide broadcasting in English by the BBC[59] and other broadcasters, caused the language to spread across the planet much faster.[60][61] In the 21st century, English is more widely spoken and written than any language has ever been.[62]

As Modern English developed, explicit norms for standard usage were published, and spread through official media such as public education and state-sponsored publications. In 1755, Samuel Johnson published his Dictionary of the English Language, which introduced standard spellings of words and usage norms. In 1828, Noah Webster published the American Dictionary of the English language to try to establish a norm for speaking and writing American English that was independent of the British standard. Within Britain, non-standard or lower class dialect features were increasingly stigmatised, leading to the quick spread of the prestige varieties among the middle classes.[63]

In modern English, the loss of grammatical case is almost complete (it is now found only in pronouns, such as he and him, she and her, who and whom), and subject–verb–object word order is mostly fixed.[63] Some changes, such as the use of do-support, have become universalised. (Earlier English did not use the word do as a general auxiliary as Modern English does; at first it was only used in question constructions, and even then was not obligatory.[64] Now, do-support with the verb have is becoming increasingly standardised.) The use of progressive forms in -ing, appears to be spreading to new constructions, and forms such as "had been being built" are becoming more common. Regularisation of irregular forms also slowly continues (e.g. dreamed instead of dreamt), and analytical alternatives to inflectional forms are becoming more common (e.g. more polite instead of politer). British English is also undergoing change under the influence of American English, fuelled by the strong presence of American English in the media.[65][66][67]

Geographical distribution

[edit]

As of 2016[update], 400 million people spoke English as their first language, and 1.1 billion spoke it as a second language.[69] English is the largest language by number of speakers, spoken by communities on every continent.[70] Estimates of second language and foreign-language speakers vary greatly depending on how proficiency is defined, from 470 million to more than 1 billion.[7] In 2003, David Crystal estimated that non-native speakers outnumbered native speakers by a ratio of three-to-one.[71]

Three circles model

[edit]Braj Kachru has categorised countries into the Three Circles of English model, according to how the language historically spread in each country, how it is acquired by the populace, and the range of uses it has there – with a country's classification able to change over time.[72][73]

"Inner-circle" countries have large communities of native English speakers; these include the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand, where the majority speaks English – and South Africa, where a significant minority speaks English. The countries with the most native English speakers are, in descending order, the United States (at least 231 million),[74] the United Kingdom (60 million),[75][76][77] Canada (19 million),[78] Australia (at least 17 million),[79] South Africa (4.8 million),[80] Ireland (4.2 million), and New Zealand (3.7 million).[81] In these countries, children of native speakers learn English from their parents, and local people who speak other languages and new immigrants learn English to communicate in their neighbourhoods and workplaces.[82] Inner-circle countries are the base from which English spreads to other regions of the world.[72]

"Outer-circle" countries – such as the Philippines,[83] Jamaica,[84] India, Pakistan, Singapore,[85] Malaysia, and Nigeria[86][87] – have much smaller proportions of native English speakers, but use of English as a second language in education, government, or domestic business is significant, and its use for instruction in schools and official government operations is routine.[88] These countries have millions of native speakers on dialect continua, which range from English-based creole languages to standard varieties of English used in inner-circle countries. They have many more speakers who acquire English as they grow up through day-to-day use and exposure to English-language broadcasting, especially if they attend schools where English is the language of instruction. Varieties of English learned by non-native speakers born to English-speaking parents may be influenced, especially in their grammar, by the other languages spoken by those learners – with most including words rarely used by native speakers in inner-circle countries, as well as grammatical and phonological differences from inner-circle varieties.[82]

"Expanding-circle" countries are where English is taught as a foreign language[89] – though the character of English as a first, second, or foreign language in a given country is often debatable, and may change over time.[88] For example, in countries like the Netherlands, an overwhelming majority of the population can speak English,[90] and it is often used in higher education and to communicate with foreigners.[91]

Pluricentric English

[edit]English is a pluricentric language, which means that no one national authority sets the standard for use of the language.[92][93][94][95] Spoken English, including English used in broadcasting, generally follows national pronunciation standards that are established by custom rather than by regulation. International broadcasters are usually identifiable as coming from one country rather than another through their accents,[96] but newsreader scripts are also composed largely in international standard written English. The norms of standard written English are maintained purely by the consensus of educated English speakers around the world, without any oversight by any government or international organisation.[97]

American listeners readily understand most British broadcasting, and British listeners readily understand most American broadcasting. Most English speakers around the world can understand radio programmes, television programmes, and films from many parts of the English-speaking world.[98] Both standard and non-standard varieties of English can include both formal or informal styles, distinguished by word choice and syntax and use both technical and non-technical registers.[99]

The settlement history of the English-speaking inner circle countries outside Britain helped level dialect distinctions and produce koiné forms of English in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.[100] The majority of immigrants to the United States without British ancestry rapidly adopted English after arrival. Now the majority of the United States population are monolingual English speakers.[74][101]

- Australia has no official languages at the federal or state level.[102]

- In Canada, English and French share an official status at the federal level.[103][104] English has official or co-official status in six provinces and three territories, while three provinces have none and Quebec's only official language is French.[105]

- English is the official second language of Ireland, while Irish is the first.[106]

- While New Zealand is majority English-speaking, its two official languages are Māori[107] and New Zealand Sign Language.[108]

- The United Kingdom does not have an official language. In Wales and Northern Ireland, English is co-official alongside Welsh[109] and Irish[110] respectively. Neither Scotland nor England have an official language.

- In the United States, English was designated the official language of the country by Executive Order 14224 in 2025.[111] English has additional official or co-official status at the state level in 32 states, and all 5 territories;[112] 18 states and the District of Columbia have no official language.

English as a global language

[edit]

Modern English is sometimes described as the first global lingua franca,[60][115] or as the first world language.[116][117] English is the world's most widely used language in newspaper publishing, book publishing, international telecommunications, scientific publishing, international trade, mass entertainment, and diplomacy.[117] Parity with French as a language of diplomacy had been achieved by Treaty of Versailles negotiations in 1919.[118] By the time the United Nations was founded at the end of World War II, English had become pre-eminent;[119] it is one of six official languages of the United Nations.[120] and is now the main worldwide language of diplomacy and international relations.[121] Many other worldwide international organisations, including the International Olympic Committee, specify English as a working language or official language of the organisation. Many regional international organisations, such as the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN),[61] and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) use English as their sole working language, despite most members not being countries with a majority of native English speakers. While the EU allows member states to designate any of the national languages as an official language of the Union, in practice English is the main working language of EU organisations.[122] English serves as the basis for the required controlled natural languages[123] Seaspeak and Airspeak, used as international languages of seafaring[124] and aviation.[125]

English is the most frequently taught foreign language in the world.[60][61] Most people learning English do so for practical reasons, as opposed to ideological reasons.[126] In EU countries, English is the most widely spoken foreign language in 19 of the 25 member states where it is not an official language (that is, the countries other than Ireland and Malta). In a 2012 official Eurobarometer poll (conducted when the UK was still a member of the EU), 38 percent of the EU respondents outside the countries where English is an official language said they could speak English well enough to have a conversation in that language. The next most commonly mentioned foreign language, French (which is the most widely known foreign language in the UK and Ireland), could be used in conversation by 12 percent of respondents.[127] The global influence of English has led to concerns about language death,[128] and to claims of linguistic imperialism,[129] and has provoked resistance to the spread of English; however, the number of speakers continues to increase because many people around the world think English provides them with better employment opportunities and increased quality of life.[130]

Working knowledge of English has become a requirement in a number of occupations and professions such as medicine[131] and computing. Though it formerly had parity with French and German in scientific research, English now dominates the field.[132] Its importance in scientific publishing is such that over 80 percent of scientific journal articles indexed by Chemical Abstracts in 1998 were written in English, as were 90 percent of all articles in natural science publications by 1996, and 82 percent of articles in humanities publications by 1995.[133]

As decolonisation proceeded throughout the British Empire in the 1950s and 1960s, former colonies often did not reject English but rather continued to use it as independent countries setting their own language policies.[57][58][134] For example, English is one of the official languages of India. Many Indians have shifted from associating the language with colonialism to associating it with economic progress.[135] English is widely used in media and literature, with India being the third-largest publisher of English-language books in the world, after the US and UK.[136] However, less than 5 percent of the population speak English fluently, with the country's native English speakers numbering in the low hundreds of thousands.[137][138] In 2004, David Crystal claimed India had the largest population of people able to speak or understand English in the world,[139] though most scholars estimate the US remains home to a larger English-speaking population.[140] Many English speakers in Africa have become part of an "Afro-Saxon" language community that unites Africans from different countries.[141] Regarding its future development, it is considered most likely that English will continue to function as a koiné language, with a standard form that unifies speakers around the world.[142]

Phonology

[edit]English phonology and phonetics differ from one dialect to another, usually without interfering with mutual communication. Phonological variation affects the inventory of phonemes (speech sounds that distinguish meaning), and phonetic variation consists in differences in pronunciation of the phonemes.[143] This overview mainly describes Received Pronunciation (RP) and General American (GA), the standard varieties of the United Kingdom and the United States respectively.[144][145][146]

Consonants

[edit]Most English dialects share the same 24 consonant phonemes (or 26, if marginal /x/ and glottal stop /ʔ/ are included). The consonant inventory shown below is valid for California English,[147] and for RP.[148]

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | (ʔ) | ||||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | |||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | (x) | h | |||||||

| Approximant | Central | ɹ | j | w | |||||||||||||

| Lateral | l | ||||||||||||||||

For pairs of obstruents (stops, affricates, and fricatives) such as /p b/, /tʃ dʒ/, and /s z/, the first is fortis (strong) and the second is lenis (weak). Fortis obstruents, such as /p tʃ s/ are pronounced with more muscular tension and breath force than lenis consonants, such as /b dʒ z/, and are always voiceless. Lenis consonants are partly voiced at the beginning and end of utterances, and fully voiced between vowels. Fortis stops such as /p/ have additional articulatory or acoustic features in most dialects: they are aspirated [pʰ] when they occur alone at the beginning of a stressed syllable, often unaspirated in other cases, and often unreleased [p̚] or pre-glottalised [ʔp] at the end of a syllable. In a single-syllable word, a vowel before a fortis stop is shortened: e.g. nip has a noticeably shorter vowel (phonetically, not phonemically) than nib [nɪˑb̥] (see below).[149]

- Lenis stops: bin [b̥ɪˑn], about [əˈbaʊt], nib [nɪˑb̥]

- Fortis stops: pin [pʰɪn]; spin [spɪn]; happy [ˈhæpi]; nip [nɪp̚] or [nɪʔp]

In RP, the lateral approximant /l/ has two main allophones (pronunciation variants): the clear or plain [l], as in light, and the dark or velarised [ɫ], as in full.[150] GA has dark l in most cases.[151]

- Clear l: RP light [laɪt]

- Dark l: RP and GA full [fʊɫ], GA light [ɫaɪt]

All sonorants (liquids /l, r/ and nasals /m, n, ŋ/) devoice when following a voiceless obstruent, and they are syllabic when following a consonant at the end of a word.[152]

- Voiceless sonorants: clay [kl̥eɪ̯]; snow RP [sn̥əʊ̯], GA [sn̥oʊ̯]

- Syllabic sonorants: paddle [ˈpad.l̩], button [ˈbʌt.n̩]

Vowels

[edit]| RP | GA | Word |

|---|---|---|

| iː | i | need |

| ɪ | bid | |

| e | ɛ | bed |

| æ | back | |

| ɑː | ɑ | bra |

| ɒ | box | |

| ɔ, ɑ | cloth | |

| ɔː | paw | |

| uː | u | food |

| ʊ | good | |

| ʌ | but | |

| ɜː | ɜɹ | bird |

| ə | comma | |

The pronunciation of vowels varies a great deal between dialects and is one of the most detectable aspects of a speaker's accent. The accompanying table below lists the vowel phonemes in RP and GA, with example words from lexical sets. The vowels are represented with symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet; those given for RP are standard in British dictionaries and other publications.[153]

In RP, vowel length is phonemic; long vowels are marked with a triangular colon ⟨ː⟩ in the table above, such as the vowel of need [niːd] as opposed to bid [bɪd].[154] In GA, vowel length is non-distinctive.[155]

In both RP and GA, vowels are phonetically shortened before fortis consonants in the same syllable, like /t tʃ f/, but not before lenis consonants like /d dʒ v/ or in open syllables: thus, the vowels of rich [rɪtʃ], neat [nit], and safe [seɪ̯f] are noticeably shorter than the vowels of ridge [rɪˑdʒ], need [niˑd], and save [seˑɪ̯v], and the vowel of light [laɪ̯t] is shorter than that of lie [laˑɪ̯]. Because lenis consonants are frequently voiceless at the end of a syllable, vowel length is an important cue as to whether the following consonant is lenis or fortis.[156]

The vowel /ə/ only occurs in unstressed syllables and is more open in quality in stem-final positions.[157][158] Some dialects do not contrast /ɪ/ and /ə/ in unstressed positions, such that rabbit and abbot rhyme and Lenin and Lennon are homophonous, a dialectal feature called the weak vowel merger.[159] GA /ɜr/ and /ər/ are realised as an r-coloured vowel [ɚ], as in further [ˈfɚðɚ] (phonemically /ˈfɜrðər/), which in RP is realised as [ˈfəːðə] (phonemically /ˈfɜːðə/).[160]

Phonotactics

[edit]An English syllable includes a syllable nucleus consisting of a vowel sound. Syllable onset and coda (start and end) are optional. A syllable can start with up to three consonant sounds, as in sprint /sprɪnt/, and end with up to five, as in (for some dialects) angsts /aŋksts/. This gives an English syllable a structure of (CCC)V(CCCCC) – where C represents a consonant and V a vowel. The word strengths /strɛŋkθs/ is thus close to the most complex syllable possible in English. The consonants that may appear together in onsets or codas are restricted, as is the order in which they may appear. Onsets can only have four types of consonant clusters: a stop and approximant, as in play; a voiceless fricative and approximant, as in fly or sly; s and a voiceless stop, as in stay; and s, a voiceless stop, and an approximant, as in string.[161] Clusters of nasal and stop are only allowed in codas. Clusters of obstruents always agree in voicing, and clusters of sibilants and of plosives with the same point of articulation are prohibited. Several consonants have limited distributions: /h/ can only occur in syllable-initial position, and /ŋ/ only in syllable-final position.[162]

Stress, rhythm, and intonation

[edit]Stress plays an important role in English. Certain syllables are stressed, while others are unstressed. Stress is a combination of duration, intensity, vowel quality, and sometimes changes in pitch. Stressed syllables are pronounced longer and louder than unstressed syllables, and vowels in unstressed syllables are frequently reduced while vowels in stressed syllables are not.[163]

Stress in English is phonemic. For instance, the word contract is stressed on the first syllable (/ˈkɒntrækt/ KON-trakt) when used as a noun, but on the last syllable (/kənˈtrækt/ kən-TRAKT) for most meanings (for example, "reduce in size") when used as a verb.[164][165][166] Here stress is connected to vowel reduction: in the noun "contract" the first syllable is stressed and has the unreduced vowel /ɒ/, but in the verb "contract" the first syllable is unstressed and its vowel is reduced to /ə/. Stress is also used to distinguish between words and phrases, so that a compound word receives a single stress unit, but the corresponding phrase has two: e.g. "a burnout" (/ˈbɜːrnaʊt/) versus "to burn out" (/ˈbɜːrn ˈaʊt/), and "a hotdog" (/ˈhɒtdɒɡ/) versus "a hot dog" (/ˈhɒt ˈdɒɡ/).[167]

In terms of rhythm, English is generally described as a stress-timed language, meaning that the amount of time between stressed syllables tends to be equal.[168] Stressed syllables are pronounced longer, but unstressed syllables (syllables between stresses) are shortened. Vowels in unstressed syllables are shortened as well, and vowel shortening causes changes in vowel quality: vowel reduction.[169]

Regional variation

[edit]| United States |

Canada | Republic of Ireland |

Northern Ireland |

Scotland | England | Wales | South Africa |

Australia | New Zealand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| father–bother merger | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| /ɒ/ is unrounded | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| /ɜr/ is pronounced [ɚ] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| cot–caught merger | Possibly | Yes | Possibly | Yes | Yes | |||||

| fool–full merger | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| /t, d/ flapping | Yes | Yes | Possibly | Often | Rarely | Rarely | Rarely | Rarely | Yes | Often |

| trap–bath split | Possibly | Possibly | Often | Yes | Yes | Often | Yes | |||

| non-rhoticity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| close vowels for /æ, ɛ/ | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| /l/ can always be pronounced [ɫ] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| /ɑː/ is fronted before /r/ | Possibly | Possibly | Yes | Yes |

| Lexical set | RP | GA | Can | Sound change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THOUGHT | /ɔː/ | /ɔ/ or /ɑ/ | /ɑ/ | cot–caught merger |

| CLOTH | /ɒ/ | lot–cloth split | ||

| LOT | /ɑ/ | father–bother merger | ||

| PALM | /ɑː/ | |||

| BATH | /æ/ | /æ/ | trap–bath split | |

| TRAP | /æ/ |

Varieties of English vary the most in pronunciation of vowels. The best-known national varieties used as standards for education in non-English-speaking countries are British (BrE) and American (AmE). Countries such as Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and South Africa have their own standard varieties which are less often used as standards for education internationally.[170]

English has undergone many historical sound changes, some of them affecting all varieties, and others affecting only a few. Most standard varieties are affected by the Great Vowel Shift, which changed the pronunciation of long vowels, but a few dialects have slightly different results. In North America, a number of chain shifts such as the Northern Cities Vowel Shift and Canadian Shift have produced very different vowel landscapes in some regional accents.[171]

Some dialects have fewer or more consonant phonemes and phones than the standard varieties. Some conservative varieties like Scottish English have a voiceless [ʍ] sound in whine that contrasts with the voiced [w] in wine, but most other dialects pronounce both words with voiced [w], a dialect feature called wine–whine merger. The voiceless velar fricative sound /x/ is found in Scottish English, which distinguishes loch /lɔx/ from lock /lɔk/. Accents like Cockney with "h-dropping" lack the glottal fricative /h/, and dialects with th-stopping and th-fronting like African-American Vernacular and Estuary English do not have the dental fricatives /θ, ð/, but replace them with dental or alveolar stops /t, d/ or labiodental fricatives /f, v/.[172][173] Other changes affecting the phonology of local varieties are processes such as yod-dropping, yod-coalescence, and reduction of consonant clusters.[174][page needed]

GA and RP vary in their pronunciation of historical /r/ after a vowel at the end of a syllable (in the syllable coda). GA is a rhotic dialect, meaning that it pronounces /r/ at the end of a syllable, but RP is non-rhotic, meaning that it loses /r/ in that position. English dialects are classified as rhotic or non-rhotic depending on whether they elide /r/ like RP or keep it like GA.[175]

There is complex dialectal variation in words with the open front and open back vowels /æ ɑː ɒ ɔː/. These four vowels are only distinguished in RP, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. In GA, these vowels merge to three /æ ɑ ɔ/,[176] and in Canadian English, they merge to two /æ ɑ/.[177]

Grammar

[edit]Typical for an Indo-European language, English grammar follows accusative morphosyntactic alignment. Unlike other Indo-European languages, English has largely abandoned the inflectional case system in favour of analytic constructions. Only the personal pronouns retain morphological case more strongly than any other word class. English distinguishes at least seven major word classes: verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, determiners (including articles), prepositions, and conjunctions. Some analyses add pronouns as a class separate from nouns, and subdivide conjunctions into subordinators and coordinators, and add the class of interjections.[178] English also has a rich set of auxiliary verbs, such as have and do, expressing the categories of mood and aspect. Questions are marked by do-support, wh-movement (fronting of question words beginning with wh-) and word order inversion with some verbs.[179]

Some traits typical of Germanic languages persist in English, such as the distinction between irregularly inflected strong stems inflected through ablaut (i.e. changing the vowel of the stem, as in the pairs speak / spoke and foot / feet) and weak stems inflected through affixation (such as love / loved, hand / hands).[180] Vestiges of the case and gender system are found in the pronoun system (he / him, who / whom); similarly, traces of more complex verb conjugation are seen in the inflection of the copula verb to be.[180]

The seven word classes are exemplified in this sample sentence:[181]

| The | chairman | of | the | committee | and | the | loquacious | politician | clashed | violently | when | the | meeting | started. |

| Det. | Noun | Prep. | Det. | Noun | Conj. | Det. | Adj. | Noun | Verb | Advb. | Conj. | Det. | Noun | Verb |

Nouns and noun phrases

[edit]English nouns are only inflected for number and possession. New nouns can be formed through derivation or compounding. They are semantically divided into proper nouns (names) and common nouns. Common nouns are in turn divided into concrete and abstract nouns, and grammatically into count nouns and mass nouns.[182]

Most count nouns are inflected for plural number through the use of the plural suffix -s, but a few nouns have irregular plural forms. Mass nouns can only be pluralised through the use of a count noun classifier, e.g. "one loaf of bread", "two loaves of bread".[183]

Regular plural formation:

- Singular: cat, dog

- Plural: cats, dogs

Irregular plural formation:

- Singular: man, woman, foot, fish, ox, knife, mouse

- Plural: men, women, feet, fish, oxen, knives, mice

Possession can be expressed either by the possessive enclitic -s (also traditionally called a genitive suffix), or by the preposition of. Historically the -s possessive has been used for animate nouns, whereas the of possessive has been reserved for inanimate nouns. Today this distinction is less clear, and many speakers use -s also with inanimates. Orthographically the possessive -s is separated from a singular noun with an apostrophe. If the noun is plural formed with -s the apostrophe follows the -s.[179]

Possessive constructions:

- With -s: "The woman's husband's child"

- With of: "The child of the husband of the woman"

Nouns can form noun phrases (NPs) where they are the syntactic head of the words that depend on them such as determiners, quantifiers, conjunctions or adjectives.[184] Noun phrases can be short, such as the man, composed only of a determiner and a noun. They can also include modifiers such as adjectives (e.g. red, tall, all) and specifiers such as determiners (e.g. the, that). But they can also tie together several nouns into a single long NP, using conjunctions such as and, or prepositions such as with, e.g. "the tall man with the long red trousers and his skinny wife with the spectacles" (this NP uses conjunctions, prepositions, specifiers, and modifiers). Regardless of length, an NP functions as a syntactic unit.[179] For example, the possessive enclitic can, in cases which do not lead to ambiguity, follow the entire noun phrase, as in "The President of India's wife", where the enclitic follows India and not President.

The class of determiners is used to specify the noun they precede in terms of definiteness, where the marks a definite noun and a or an an indefinite one. A definite noun is assumed by the speaker to be already known by the interlocutor, whereas an indefinite noun is not specified as being previously known. Quantifiers, which include one, many, some and all, are used to specify the noun in terms of quantity or number. The noun must agree with the number of the determiner, e.g. one man (sg.) but all men (pl.). Determiners are the first constituents in a noun phrase.[185]

Adjectives

[edit]English adjectives are words such as good, big, interesting, and Canadian that most typically modify nouns, denoting characteristics of their referents (e.g. "a red car"). As modifiers, they come before the nouns they modify and after determiners.[186] English adjectives also function as predicative complements (e.g. "the child is happy").[187]

In Modern English, adjectives are not inflected so as to agree in form with the noun they modify, as in most other Indo-European languages. For example, in the phrases "the slender boy", and "many slender girls", the adjective slender does not change form to agree with either the number or gender of the noun.[188]

Some adjectives are inflected for degree of comparison, with the positive degree unmarked, the suffix -er marking the comparative, and -est marking the superlative: "a small boy", "the boy is smaller than the girl", "that boy is the smallest". Some adjectives have irregular suppletive comparative and superlative forms, such as good, better, and best. Other adjectives have comparatives formed by periphrastic constructions, with the adverb more marking the comparative, and most marking the superlative: happier or more happy, the happiest or most happy.[189] There is some variation among speakers regarding which adjectives use inflected or periphrastic comparison, and some studies have shown a tendency for the periphrastic forms to become more common at the expense of the inflected form.[190]

Determiners

[edit]English determiners are words such as the, each, many, some, and which, occurring most typically in noun phrases before the head nouns and any modifiers and marking the noun phrase as definite or indefinite.[191] They often agree with the noun in number. They do not typically inflect for degree of comparison.

Pronouns, case, and person

[edit]English pronouns conserve many traits of case and gender inflection. The personal pronouns retain a difference between subjective and objective case in most persons (I/me, he/him, she/her, we/us, they/them) as well as an animateness distinction in the third person singular (distinguishing it from the three sets of animate third person singular pronouns) and an optional gender distinction in the animate third person singular (distinguishing between feminine she/her, epicene they/them, and masculine he/him.[192][193] The subjective case corresponds to the Old English nominative case, and the objective case is used in the sense both of the previous accusative case (for a patient, or direct object of a transitive verb), and of the Old English dative case (for a recipient or indirect object of a transitive verb).[194][195] The subjective is used when the pronoun is the subject of a finite clause, otherwise the objective is used.[196] While grammarians such as Henry Sweet[197] and Otto Jespersen[198] noted that the English cases did not correspond to the traditional Latin-based system, some contemporary grammars, including The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, retain traditional nominative and accusative labels for the cases.[199]

Possessive pronouns exist in dependent and independent forms; the dependent form functions as a determiner specifying a noun (as in my chair), while the independent form can stand alone as if it were a noun (e.g. "the chair is mine").[200] Grammatical person in English no longer distinguishes between formal and informal pronouns of address, with the second person singular familiar pronoun thou that previously existed in the language having fallen almost entirely out of use by the 18th century.[201]

Both the second and third persons share pronouns between the plural and singular:

- Plural and singular are always identical (you, your, yours) in the second person (except in the reflexive form: yourself/yourselves) in most dialects. Some dialects have introduced innovative second person plural pronouns, such as y'all (found in Southern American English and African-American Vernacular English), youse (found in Australian English), or ye (in Hiberno-English).

- In the third person, the they/them series of pronouns (they, them, their, theirs, themselves) are used in both plural and singular, and are the only pronouns available for the plural. In the singular, the they/them series (sometimes with the addition of the singular-specific reflexive form themself) serve as a gender-neutral set of pronouns. These pronouns are becoming more accepted, especially as part of the LGBTQ culture.[192][202][203]

| Person | Subjective case | Objective case | Dependent possessive | Independent possessive | Reflexive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st, singular | I | me | my | mine | myself |

| 2nd, singular | you | you | your | yours | yourself |

| 3rd, singular | he/she/it/they | him/her/it/them | his/her/its/their | his/hers/its/theirs | himself/herself/itself/themself/themselves |

| 1st, plural | we | us | our | ours | ourselves |

| 2nd, plural | you | you | your | yours | yourselves |

| 3rd, plural | they | them | their | theirs | themselves |

Pronouns are used to refer to entities deictically or anaphorically. A deictic pronoun points to some person or object by identifying it relative to the speech situation – for example, the pronoun I identifies the speaker, and the pronoun you, the addressee. Anaphoric pronouns such as that refer back to an entity already mentioned or assumed by the speaker to be known by the audience, for example in the sentence "I already told you that". The reflexive pronouns are used when the oblique argument is identical to the subject of a phrase (e.g. "he sent it to himself" or "she braced herself for impact").[204]

Prepositions

[edit]Prepositional phrases (PP) are phrases composed of a preposition and one or more nouns, e.g. "with the dog", "for my friend", "to school", "in England".[205] English prepositions have a wide range of uses – including describing movement, place, and other relations between entities, as well as functions that are syntactic in nature, like introducing complement clauses and oblique arguments of verbs.[205] For example, in the phrase "I gave it to him", the preposition to marks the indirect object of the verb to give. Traditionally words were only considered prepositions if they governed the case of the noun they preceded, for example causing the pronouns to use the objective rather than subjective form, "with her", "to me", "for us". But some contemporary grammars no longer consider government of case to be the defining feature of the class of prepositions, rather defining prepositions as words that can function as the heads of prepositional phrases.[206]

Verbs and verb phrases

[edit]English verbs are inflected for tense and aspect and marked for agreement with a third person present singular subject. Only the copula verb to be is still inflected for agreement with the plural and first and second person subjects.[189] Auxiliary verbs such as have and be are paired with verbs in the infinitive, past, or progressive forms. They form complex tenses, aspects, and moods. Auxiliary verbs differ from other verbs in that they can be followed by the negation, and in that they can occur as the first constituent in a question sentence.[207][208]

Most verbs have six inflectional forms. The primary forms are a plain present, a third person singular present, and a preterite (past) form. The secondary forms are a plain form used for the infinitive, a gerund-participle and a past participle.[209] The verb to be – which among other uses in English functions as the primary auxiliary verb indicating the imperfective aspect (e.g. "I am going"), as well as the copula[210] – is the only verb to retain some of its original conjugation, and takes different inflectional forms depending on the subject. The first person present form is am, the third person singular form is is, and the form are is used in the second person singular and all three plurals. The only verb past participle is been and its gerund-participle is being.[211]

| Inflection | Strong | Regular |

|---|---|---|

| Plain present | take | love |

| 3rd person sg. present |

takes | loves |

| Preterite | took | loved |

| Plain (infinitive) | take | love |

| Gerund–participle | taking | loving |

| Past participle | taken | loved |

Tense, aspect, and mood

[edit]English has two primary tenses, past (preterite) and non-past. The preterite is inflected by using the preterite form of the verb, which for the regular verbs includes the suffix -ed, and for the strong verbs either the suffix -t or a change in the stem vowel. The non-past form is unmarked except in the third person singular, which takes the suffix -s.[207]

| Present | Preterite | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | I run | I ran |

| Second person | You run | You ran |

| Third person | John runs | John ran |

English does not have future verb forms.[212] The future tense is expressed periphrastically with one of the auxiliary verbs will or shall.[213] Many varieties also use a near future constructed with the phrasal verb "be going to" (going-to future).[214]

| Future | |

|---|---|

| First person | "I will run" |

| Second person | "You will run" |

| Third person | "John will run" |

Further aspectual distinctions are shown by auxiliary verbs, primarily have and be, which show the contrast between a perfect and non-perfect past tense ("I have run" vs. "I was running"), and compound tenses such as preterite perfect ("I had been running") and present perfect ("I have been running").[215]

For the expression of mood, English uses a number of modal auxiliaries, such as can, may, will, shall and the past tense forms could, might, would, should. There are also subjunctive and imperative moods, both based on the plain form of the verb (i.e. without the third person singular -s), for use in subordinate clauses (e.g. subjunctive: "It is important that he run every day"; imperative Run!).[213]

An infinitive form, that uses the plain form of the verb and the preposition to, is used for verbal clauses that are syntactically subordinate to a finite verbal clause. Finite verbal clauses are those that are formed around a verb in the present or preterite form. In clauses with auxiliary verbs, they are the finite verbs and the main verb is treated as a subordinate clause.[216] For example, "he has to go" where only the auxiliary verb have is inflected for time and the main verb to go is in the infinitive, or in a complement clause such as "I saw him leave", where the main verb is see, which is in a preterite form, and leave is in the infinitive.

Phrasal verbs

[edit]English also makes frequent use of constructions traditionally called phrasal verbs, verb phrases that are made up of a verb root and a preposition or particle that follows the verb. The phrase then functions as a single predicate. In terms of intonation the preposition is fused to the verb, but in writing it is written as a separate word. Examples of phrasal verbs are "to get up", "to ask out", "to get together", and "to put up with". The phrasal verb frequently has a highly idiomatic meaning that is more specialised and restricted than what can be simply extrapolated from the combination of verb and preposition complement (e.g. lay off meaning terminate someone's employment).[217] Some grammarians do not consider this type of construction to form a syntactic constituent and hence refrain from using the term "phrasal verb". Instead, they consider the construction simply to be a verb with a prepositional phrase as its syntactic complement, e.g. "he woke up in the morning" and "he ran up in the mountains" are syntactically equivalent.[218]

Adverbs

[edit]The function of adverbs is to modify the action or event described by the verb by providing additional information about the manner in which it occurs.[179] Many English adverbs are derived from adjectives by appending the suffix -ly. For example, in the phrase "the woman walked quickly", the adverb quickly is derived from the adjective quick. Some commonly used adjectives have irregular adverbial forms, such as good, which has the adverbial form well.[219]

Syntax

[edit]

Modern English syntax is moderately analytic.[220] It has developed features such as modal verbs and word order as resources for conveying meaning. Auxiliary verbs mark constructions such as questions, negative polarity, the passive voice and progressive aspect.[221]

Basic constituent order

[edit]English has moved from the Germanic verb-second (V2) word order to being almost exclusively subject–verb–object (SVO).[222] The combination of SVO order and use of auxiliary verbs often creates clusters of two or more verbs at the centre of the sentence, such as "he had been hoping to try opening it".[223]

In most sentences, English only marks grammatical relations through word order.[224] The subject constituent precedes the verb and the object constituent follows it. The grammatical roles of each constituent are marked only by the position relative to the verb:

| The dog | bites | the man |

| S | V | O |

| The man | bites | the dog |

| S | V | O |

An exception is found in sentences where one of the constituents is a pronoun, in which case it is doubly marked, both by word order and by case inflection, where the subject pronoun precedes the verb and takes the subjective case form, and the object pronoun follows the verb and takes the objective case form.[225] The example below demonstrates this double marking in a sentence where both object and subject are represented with a third person singular masculine pronoun:

| He | hit | him |

| S | V | O |

Indirect objects (IO) of ditransitive verbs can be placed either as the first object in a double object construction (S V IO O), such as "I gave Jane the book" or in a prepositional phrase, such as "I gave the book to Jane".[226]

Clause syntax

[edit]English sentences may be composed of one or more clauses, that may in turn be composed of one or more phrases (e.g. noun phrases, verb phrases, prepositional phrases). A clause is built around a verb and includes its constituents, such as any noun or prepositional phrases. Within a sentence, there is always at least one main clause (or matrix clause) whereas other clauses are subordinate to a main clause. Subordinate clauses may function as arguments of the verb in the main clause. For example, in the phrase "I think (that) you are lying", the main clause is headed by the verb think, the subject is I, but the object of the phrase is the subordinate clause "(that) you are lying". The subordinating conjunction that shows that the clause that follows is a subordinate clause, but it is often omitted.[227] Relative clauses are clauses that function as a modifier or specifier to some constituent in the main clause: For example, in the sentence "I saw the letter that you received today", the relative clause "that you received today" specifies the meaning of the word letter, the object of the main clause. Relative clauses can be introduced by the pronouns who, whose, whom, and which as well as by that (which can also be omitted).[228] In contrast to many other Germanic languages there are no major differences between word order in main and subordinate clauses.[229]

Auxiliary verb constructions

[edit]English auxiliary verbs are relied upon for many functions, including the expression of tense, aspect, and mood. Auxiliary verbs form main clauses, and the main verbs function as heads of a subordinate clause of the auxiliary verb. For example, in the sentence "the dog did not find its bone", the clause "find its bone" is the complement of the negated verb did not. Subject–auxiliary inversion is used in many constructions, including focus, negation, and interrogative constructions.[230]

The verb do can be used as an auxiliary even in simple declarative sentences, where it usually serves to add emphasis, as in "I did shut the fridge." However, in the negated and inverted clauses referred to above, it is used because the rules of English syntax permit these constructions only when an auxiliary is present. Modern English does not allow the addition of the negating adverb not to an ordinary finite lexical verb, as in *"I know not" – it can only be added to an auxiliary (or copular) verb, hence if there is no other auxiliary present when negation is required, the auxiliary do is used, to produce a form like "I do not (don't) know." The same applies in clauses requiring inversion, including most questions – inversion must involve the subject and an auxiliary verb, so it is not possible to say *"Know you him?"; grammatical rules require "Do you know him?"[231]

Negation is done with the adverb not, which precedes the main verb and follows an auxiliary verb. A contracted form of not -n't can be used as an enclitic attaching to auxiliary verbs and to the copula verb to be. Just as with questions, many negative constructions require the negation to occur with do-support, thus in Modern English "I don't know him" is the correct answer to the question "Do you know him?", but not *"I know him not", although this construction may be found in older English.[232]

Passive constructions also use auxiliary verbs. A passive construction rephrases an active construction in such a way that the object of the active phrase becomes the subject of the passive phrase, and the subject of the active phrase is either omitted or demoted to a role as an oblique argument introduced in a prepositional phrase. They are formed by using the past participle either with the auxiliary verb to be or to get, although not all varieties of English allow the use of passives with get. For example, putting the sentence "she sees him" into the passive becomes "he is seen (by her)", or "he gets seen (by her)".[233]

Questions

[edit]Both yes/no questions and wh-questions in English are mostly formed using subject–auxiliary inversion ("Am I going tomorrow?", "Where can we eat?"), which may require do-support ("Do you like her?", "Where did he go?"). In most cases, interrogative words (or wh-words) – which include who, what, when, where, why, and how – appear in a fronted position. For example, in the question "What did you see?", the word what appears as the first constituent despite being the grammatical object of the sentence. When the wh-word is the subject or forms part of the subject, no inversion occurs (e.g. "Who saw the cat?"). Prepositional phrases can also be fronted when they are the questions theme (e.g. "To whose house did you go last night?"). The personal interrogative pronoun who is the only interrogative pronoun to still show inflection for case, with the variant whom serving as the objective case form, although this form may be going out of use in many contexts.[234]

Discourse level syntax

[edit]While English is a subject-prominent language, at the discourse level it tends to use a topic–comment structure, where the known information (topic) precedes the new information (comment). Because of the strict SVO syntax, the topic of a sentence generally has to be the grammatical subject of the sentence. In cases where the topic is not the grammatical subject of the sentence, it is often promoted to subject position through syntactic means. One way of doing this is through a passive construction, "the girl was stung by the bee". Another way is through a cleft sentence where the main clause is demoted to be a complement clause of a copula sentence with a dummy subject such as it or there, e.g. "it was the girl that the bee stung", "there was a girl who was stung by a bee".[235] Dummy subjects are also used in constructions where there is no grammatical subject such as with impersonal verbs (e.g. "it is raining") or in existential clauses ("there are many cars on the street"). Through the use of these complex sentence constructions with informationally vacuous subjects, English is able to maintain both a topic–comment sentence structure and a SVO syntax.[236]

Focus constructions emphasise a particular piece of new or salient information within a sentence, generally through allocating the main sentence level stress on the focal constituent. For example, "the girl was stung by a bee" (emphasising it was a bee and not, for example, a wasp that stung her), or "the girl was stung by a bee" (contrasting with another possibility, for example that it was the boy).[237] Topic and focus can also be established through syntactic dislocation, either preposing or postposing the item to be focused on relative to the main clause. For example, "That girl over there, she was stung by a bee", emphasises the girl by preposition, but a similar effect could be achieved by postposition, "she was stung by a bee, that girl over there", where reference to the girl is established as an afterthought.[238]

Cohesion between sentences is achieved through the use of deictic pronouns as anaphora (e.g. "that is exactly what I mean" where that refers to some fact known to both interlocutors, or then used to locate the time of a narrated event relative to the time of a previously narrated event).[239] Discourse markers such as oh, so, or well, also signal the progression of ideas between sentences and help to create cohesion. Discourse markers are often the first constituents in sentences. Discourse markers are also used for stance taking in which speakers position themselves in a specific attitude towards what is being said, for example, "no way is that true!" (the idiomatic marker "no way!" expressing disbelief), or "boy! I'm hungry" (the marker boy expressing emphasis). While discourse markers are particularly characteristic of informal and spoken registers of English, they are also used in written and formal registers.[240]

Vocabulary

[edit]The English lexicon consists of around 170,000 words (or 220,000, if counting obsolete words), according to an estimate based on the 1989 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.[241] Over one-half are nouns, one-quarter are adjectives, and one-seventh are verbs. Another estimate – which includes scientific jargon, prefixed and suffixed words, loanwords of extremely limited use, technical acronyms, etc. – counts around 1 million total English words.[242]

English borrows vocabulary quickly from many languages and other sources. Early studies of English vocabulary by lexicographers (scholars who study vocabulary and compile dictionaries) were impeded by a lack of comprehensive data on actual vocabulary in use from high-quality linguistic corpora[243] (collections of actual written texts and spoken passages). Many statements published before the end of the 20th century about the growth of English vocabulary over time, the dates of first use of various words in English, and the sources of English vocabulary will have to be corrected as new computerised analyses of linguistic corpus data become available.[244][245]

Word-formation processes

[edit]English forms new words from existing words or roots in its vocabulary through a variety of processes. One of the most productive processes in English is conversion,[246] using a word with a different grammatical role, for example using a noun as a verb or a verb as a noun. Another productive word-formation process is nominal compounding,[242][245] producing compound words such as babysitter or ice cream or homesick.[246]

Formation of new words, called neologisms, based on Greek or Latin roots (for example television or optometry) is a highly productive process in modern European languages like English, so much so that it is often difficult to determine in which language a neologism originated. For this reason, American lexicographer Philip Gove attributed many such words to the "international scientific vocabulary" (ISV) when compiling Webster's Third New International Dictionary (1961). Another active word-formation process in English is that of acronyms, which result from pronouncing abbreviations of longer phrases as single words, e.g. NATO, laser, scuba.[247]

Word origins

[edit]Throughout its history, English has been a particularly frequent borrower of loanwords from other languages.[249] West Germanic words in use since the Anglo-Saxon period still comprise most of the language's core vocabulary, as well as most of its most frequently used words.[250][251][242] Many sentences can be constructed without loanwords, but not without core Anglo-Saxon vocabulary.[252] English has formal and informal speech registers; informal registers, including child-directed speech, tend to be made up predominantly of Anglo-Saxon vocabulary, while Latinate vocabulary appears more frequently in legal, scientific, and academic writing.[253][254]

Prolonged and intense contact with French has resulted in English having a very high proportion of Latinate words – with French loanwords borrowed during different stages of the language's history comprising 28 percent of the English lexicon.[255] In all periods of its history, English has also borrowed words from Latin directly,[245][242] representing another 28 percent of the lexicon.[256] In turn, many of these words had originally entered Latin from Greek. Greek and Latin stems remain highly productive sources for new literary, technical, and scientific vocabulary in English.[257]

Loanwords from Old Norse primarily entered English between the 8th and 11th centuries, during the Norse colonisation of eastern and northern England, and typically displaced an Anglo-Saxon equivalent. Many represent core vocabulary – including give, get, sky, skirt, egg, and cake.[258][39]

English loans in other languages

[edit]

English has had a strong influence on the vocabulary of other languages.[255][259] The influence of English comes from such factors as opinion leaders in other countries knowing the English language, the role of English as a world lingua franca, and the large number of books and films that are translated from English into other languages.[260] That pervasive use of English leads to a conclusion in many places that English is an especially suitable language for expressing new ideas or describing new technologies. Among varieties of English, it is especially American English that influences other languages.[261] Some languages, such as Chinese, write words borrowed from English mostly as calques, while others, such as Japanese, readily take in English loanwords written in sound-indicating script.[262] Dubbed films and television programmes are an especially fruitful source of English influence on languages in Europe.[262]

Orthography

[edit]Since the 9th century, English has been written using the English alphabet, which uses the Latin script. Anglo-Saxon runes were previously used to write Old English, but only in short inscriptions; the overwhelming majority of attested writings in Old English are in the Old English Latin alphabet.[33]

English orthography is multi-layered and complex, with elements of French, Latin, and Greek spelling on top of the native Germanic system.[263] Further complications have arisen through sound changes with which the orthography has not kept pace.[50] Compared to European languages for which official organisations have promoted spelling reforms, English has spelling that is a less consistent indicator of pronunciation, and standard spellings of words that are more difficult to guess from knowing how a word is pronounced.[264] There are also systematic spelling differences between British and American English. These situations have prompted proposals for spelling reform in English.[265]

Although letters and speech sounds do not have a one-to-one correspondence in standard English spelling, spelling rules that take into account syllable structure, phonetic changes in derived words, and word accent are reliable for most English words.[266] Moreover, standard English spelling shows etymological relationships between related words that would be obscured by a closer correspondence between pronunciation and spelling – for example, the words photograph, photography, and photographic,[266] or the words electricity and electrical. While few scholars agree with Chomsky and Halle (1968) that conventional English orthography is "near-optimal",[263] there is a rationale for current English spelling patterns.[267] The standard orthography of English is the most widely used writing system in the world.[268] Standard English spelling is based on a graphomorphemic segmentation of words into written clues of what meaningful units make up each word.[269]

Readers of English can generally rely on the correspondence between spelling and pronunciation to be fairly regular for letters or digraphs used to spell consonant sounds. The letters b, d, f, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, v, w, y, z represent, respectively, the phonemes /b, d, f, h, dʒ, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, v, w, j, z/. The letters c and g normally represent /k/ and /ɡ/, but there is also a soft c pronounced /s/, and a soft g pronounced /dʒ/. The differences in the pronunciations of the letters c and g are often signalled by the following letters in standard English spelling. Digraphs used to represent phonemes and phoneme sequences include ch for /tʃ/, sh for /ʃ/, th for /θ/ or /ð/, ng for /ŋ/, qu for /kw/, and ph for /f/ in Greek-derived words. The single letter x is generally pronounced as /z/ in word-initial position and as /ks/ otherwise. There are exceptions to these generalisations, often the result of loanwords being spelled according to the spelling patterns of their languages of origin[266] or residues of proposals by scholars in the early period of Modern English to follow the spelling patterns of Latin for English words of Germanic origin.[270]

For the vowel sounds of the English language, however, correspondences between spelling and pronunciation are more irregular. There are many more vowel phonemes in English than there are single vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u, y, and very rarely w). As a result, some "long vowels" are often indicated by combinations of letters (like the oa in boat, the ow in how, and the ay in stay), or the historically based silent e (as in note and cake).[267]

The consequence of this complex orthographic history is that learning to read and write can be challenging in English. It can take longer for school pupils to become independently fluent readers of English than of many other languages, including Italian, Spanish, and German.[271] Nonetheless, there is an advantage for learners of English reading in learning the specific sound-symbol regularities that occur in the standard English spellings of commonly used words.[266] Such instruction greatly reduces the risk of children experiencing reading difficulties in English.[272][273] Making primary school teachers more aware of the primacy of morpheme representation in English may help learners learn more efficiently to read and write English.[274]

English writing also includes a system of punctuation marks that is similar to those used in most alphabetic languages around the world. The purpose of punctuation is to mark meaningful grammatical relationships in sentences to aid readers in understanding a text and to indicate features important for reading a text aloud.[275]

Dialects, accents, and varieties

[edit]Dialectologists identify many English dialects, which usually refer to regional varieties that differ from each other in terms of patterns of grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. The pronunciation of particular areas distinguishes dialects as separate regional accents. The major native dialects of English are often divided by linguists into the two extremely general categories of British English (BrE) and North American English (NAE).[276]

Britain and Ireland

[edit]

The fact that English has been spoken in England for 1,500 years explains why England has a great wealth of regional dialects.[277] Within the United Kingdom, Received Pronunciation (RP), an educated accent associated originally with South East England, has been traditionally used as a broadcast standard and is considered the most prestigious of British accents. The spread of RP (also known as BBC English) through the media has caused many traditional dialects of rural England to recede, as youths adopt the traits of the prestige variety instead of traits from local dialects. At the time of the 1950–61 Survey of English Dialects, grammar and vocabulary differed across the country, but a process of lexical attrition has led most of this variation to disappear.[278]

Nonetheless, this attrition has mostly affected dialectal variation in grammar and vocabulary. In fact, only 3% of the English population actually speak RP, the remainder speaking in regional accents and dialects with varying degrees of RP influence.[279] There is also variability within RP, particularly along class lines between Upper and Middle-class RP speakers and between native RP speakers and speakers who adopt RP later in life.[280] Within Britain, there is also considerable variation along lines of social class; some traits, though exceedingly common, are nonetheless considered "non-standard" and associated with lower-class speakers and identities. An example of this is h-dropping, which was historically a feature of lower-class London English, particularly Cockney, and can now be heard in the local accents of most parts of England. However, it remains largely absent in broadcasting and among the upper crust of British society.[281]

English in England can be divided into four major dialect regions: South East English, South West English (also known as West Country English), Midlands English and Northern English. Within each of these regions, several local dialects exist: within the Northern region, there is a division between the Yorkshire dialects, the Geordie dialect (spoken around Newcastle, in Northumbria) and the Lancashire dialects, which include the urban subdialects of Manchester (Mancunian) and Liverpool (Scouse). Having been the centre of Danish occupation during the Viking invasions of England, Northern English dialects, particularly the Yorkshire dialect, retain Norse features not found in other English varieties.[282] In the West Midlands, dialects such as Black Country (Yam Yam), and by less extent Birmingham (Brummie), preserve archaic features from Early Modern and Middle English, retaining Germanic elements such as specific grammatical structures and vocabulary.[283]