Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

American Jews

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

American Jews (Hebrew: יהודים אמריקאים, romanized: Yehudim Amerikaim; Yiddish: אמעריקאנער אידן, romanized: Amerikaner Idn) or Jewish Americans are American citizens who are Jewish, whether by ethnicity, religion, or culture.[5] According to a 2020 poll conducted by Pew Research, approximately two thirds of American Jews identify as Ashkenazi, 3% identify as Sephardic, and 1% identify as Mizrahi. An additional 6% identify as some combination of the three categories, and 25% do not identify as any particular category.[6]

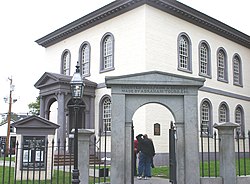

During the colonial era, Sephardic Jews who arrived via Portugal and via Brazil (Dutch Brazil) – see Congregation Shearith Israel – represented the bulk of America's then small Jewish population. While their descendants are a minority nowadays, they represent the remainder of those original American Jews along with an array of other Jewish communities, including more recent Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Beta Israel-Ethiopian Jews, various other Jewish ethnic groups, as well as a smaller number of gerim (converts). The American Jewish community manifests a wide range of Jewish cultural traditions, encompassing the full spectrum of Jewish religious observance.

Depending on religious definitions and varying population data, the United States has the largest or second largest Jewish community in the world, after Israel. As of 2020, the American Jewish population is estimated at 7.5 million people, accounting for 2.4% of the total US population. This includes 4.2 million adults who identify their religion as Jewish, 1.5 million Jewish adults who identify with no religion, and 1.8 million Jewish children.[1] It is estimated that up to 15 million Americans are part of the "enlarged" American Jewish population, accounting for 4.5% of the total US population, consisting of those who have at least one Jewish grandparent and would be eligible for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return.[7]

History

[edit]Jews were present in the Thirteen Colonies since the mid-17th century.[8][9] However, they were few in number, with at most 200 to 300 having arrived by 1700.[10] Those early arrivals were mostly Sephardi Jewish immigrants, of Western Sephardic (also known as Spanish and Portuguese Jewish) ancestry,[11] but by 1720, Ashkenazi Jews from diaspora communities in Central and Eastern Europe predominated.[10]

For the first time, the English Plantation Act 1740 permitted Jews to become British citizens and emigrate to the colonies. The first famous Jew in US history was Chaim Salomon, a Polish-born Jew who emigrated to New York and played an important role in the American Revolution. He was a successful financier who supported the patriotic cause and helped raise most of the money needed to finance the American Revolution.[12]

Despite some of them being denied the right to vote or hold office in local jurisdictions, Sephardi Jews became active in community affairs in the 1790s, after they were granted political equality in the five states where they were most numerous.[13] Until about 1830, Charleston, South Carolina had more Jews than anywhere else in North America. Large-scale Jewish immigration commenced in the 19th century, when, by mid-century, many German Jews had arrived, migrating to the United States in large numbers due to antisemitic laws and restrictions in their countries of birth.[14] They primarily became merchants and shop-owners. Gradually early Jewish arrivals from the east coast would travel westward, and in the fall of 1819 the first Jewish religious services west of the Appalachian Range were conducted during the High Holidays in Cincinnati, the oldest Jewish community in the Midwest. Gradually the Cincinnati Jewish community would adopt novel practices under the leadership Rabbi Isaac Meyer Wise, the father of Reform Judaism in the United States,[15] such as the inclusion of women in minyan.[16] A large community grew in the region with the arrival of German and Lithuanian Jews in the latter half of the 1800s, leading to the establishment of Manischewitz, one of the largest producers of American kosher products and now based in New Jersey, and the oldest continuously published Jewish newspaper in the United States, and second-oldest continuous published in the world, The American Israelite, established in 1854 and still extant in Cincinnati.[17] By 1880 there were approximately 250,000 Jews in the United States, many of them being the educated, and largely secular, German Jews, although a minority population of the older Sephardi Jewish families remained influential.

Jewish migration to the United States increased dramatically in the early 1880s, as a result of persecution and economic difficulties in parts of Eastern Europe. Most of these new immigrants were Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews, most of whom arrived from poor diaspora communities of the Russian Empire and the Pale of Settlement, located in modern-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova. During the same period, great numbers of Ashkenazic Jews also arrived from Galicia, at that time the most impoverished region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with a heavy Jewish urban population, driven out mainly by economic reasons. Many Jews also emigrated from Romania. Over 2,000,000 Jews landed between the late 19th century and 1924 when the Immigration Act of 1924 restricted immigration. Most settled in the New York metropolitan area, establishing the world's major concentrations of the Jewish population. In 1915, the circulation of the daily Yiddish newspapers was half a million in New York City alone, and 600,000 nationally. In addition, thousands more subscribed to the numerous weekly papers and the many magazines in Yiddish.[18]

At the beginning of the 20th century, these newly arrived Jews built support networks consisting of many small synagogues and Landsmanshaften (German and Yiddish for "Countryman Associations") for Jews from the same town or village. American Jewish writers of the time urged assimilation and integration into the wider American culture, and Jews quickly became part of American life. Approximately 500,000 American Jews (or half of all Jewish males between 18 and 50) fought in World War II, and after the war younger families joined the new trend of suburbanization. There, Jews became increasingly assimilated and demonstrated rising intermarriage. The suburbs facilitated the formation of new centers, as Jewish school enrollment more than doubled between the end of World War II and the mid-1950s, while synagogue affiliation jumped from 20% in 1930 to 60% in 1960; the fastest growth came in Reform and, especially, Conservative congregations.[19] More recent waves of Jewish emigration from Russia and other regions have largely joined the mainstream American Jewish community.

Americans of Jewish descent have been successful in many fields and aspects over the years.[20][21] The Jewish community in America has gone from being part of the lower class of society, with numerous employments barred to them,[22] to being a group with a high concentrations in members of the academia and a per capita income higher than the average in the United States.[23][24][25]

| < $30,000 | $30,000–49,999 | $50,000–99,999 | $100,000+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16% | 15% | 24% | 44% |

Self-identity

[edit]Scholars debate whether the historical experience of Jews in the United States has been such a unique experience as to validate American exceptionalism.[27] Korelitz (1996) shows how American Jews during the late 19th and early 20th centuries abandoned a racial definition of Jewishness in favor of one that embraced ethnicity. The key to understanding this transition from a racial self-definition to a cultural or ethnic one can be found in the Menorah Journal between 1915 and 1925. During this time contributors to the Menorah promoted a cultural, rather than a racial, religious, or other views of Jewishness as a means to define Jews in a world that threatened to overwhelm and absorb Jewish uniqueness. The journal represented the ideals of the menorah movement established by Horace M. Kallen and others to promote a revival in Jewish cultural identity and combat the idea of race as a means to define or identify peoples.[28]

Siporin (1990) states that the family folklore of ethnic Jews provides insights that illuminate collective history and transform it into art, and that these insights tell us how Jews have survived being uprooted and transformed. Many immigrant narratives bear a theme of the arbitrary nature of fate and the reduced state of immigrants in a new culture. By contrast, ethnic family narratives tend to show the ethnicity more in charge of his life, and perhaps in danger of losing his Jewishness altogether. Some stories show how a family member successfully negotiated the conflict between ethnic and American identities.[29] After 1960, memories of the Holocaust, together with the Six-Day War in 1967 had major impacts on fashioning Jewish ethnic identity. Some have argued that the Holocaust highlighted for Jews the importance of their ethnic identity at a time when other minorities were asserting their own.[30][31][32] The world's largest Jewish gathering outside of Israel occurred in Edison, central New Jersey, on December 1, 2024.[33]

Politics

[edit]| Election year |

Candidate of the Democratic Party |

% of Jewish vote to the Democratic Party |

Result of the Democratic Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 | Woodrow Wilson | 55 | Won |

| 1920 | James M. Cox | 19 | Lost |

| 1924 | John W. Davis | 51 | Lost |

| 1928 | Al Smith | 72 | Lost |

| 1932 | Franklin D. Roosevelt | 82 | Won |

| 1936 | 85 | Won | |

| 1940 | 90 | Won | |

| 1944 | 90 | Won | |

| 1948 | Harry Truman | 75 | Won |

| 1952 | Adlai Stevenson | 64 | Lost |

| 1956 | 60 | Lost | |

| 1960 | John F. Kennedy | 82 | Won |

| 1964 | Lyndon B. Johnson | 90 | Won |

| 1968 | Hubert Humphrey | 81 | Lost |

| 1972 | George McGovern | 65 | Lost |

| 1976 | Jimmy Carter | 71 | Won |

| 1980 | 45 | Lost | |

| 1984 | Walter Mondale | 67 | Lost |

| 1988 | Michael Dukakis | 64 | Lost |

| 1992 | Bill Clinton | 80 | Won |

| 1996 | 78 | Won | |

| 2000 | Al Gore | 79 | Lost |

| 2004 | John Kerry | 76 | Lost |

| 2008 | Barack Obama | 78 | Won |

| 2012 | 69 | Won | |

| 2016 | Hillary Clinton | 71[35] | Lost |

| 2020 | Joe Biden | 69[36] | Won |

| 2024 | Kamala Harris | 63[37] | Lost |

| Election year |

Candidate of the Republican Party |

% of Jewish vote to the Republican Party |

Result of the Republican Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 | Charles E. Hughes | 45 | Lost |

| 1920 | Warren G. Harding | 43 | Won |

| 1924 | Calvin Coolidge | 27 | Won |

| 1928 | Herbert Hoover | 28 | Won |

| 1932 | 18 | Lost | |

| 1936 | Alf Landon | 15 | Lost |

| 1940 | Wendell Willkie | 10 | Lost |

| 1944 | Thomas Dewey | 10 | Lost |

| 1948 | 10 | Lost | |

| 1952 | Dwight D. Eisenhower | 36 | Won |

| 1956 | 40 | Won | |

| 1960 | Richard Nixon | 18 | Lost |

| 1964 | Barry Goldwater | 10 | Lost |

| 1968 | Richard Nixon | 17 | Won |

| 1972 | 35 | Won | |

| 1976 | Gerald Ford | 27 | Lost |

| 1980 | Ronald Reagan | 39 | Won |

| 1984 | 31 | Won | |

| 1988 | George H. W. Bush | 35 | Won |

| 1992 | 11 | Lost | |

| 1996 | Bob Dole | 16 | Lost |

| 2000 | George W. Bush | 19 | Won |

| 2004 | 24 | Won | |

| 2008 | John McCain | 22 | Lost |

| 2012 | Mitt Romney | 30 | Lost |

| 2016 | Donald Trump | 24[35] | Won |

| 2020 | 30[36] | Lost | |

| 2024 | 36[38] | Won |

In New York City, while the German-Jewish community was well established 'uptown', the more numerous Jews who migrated from Eastern Europe faced tension 'downtown' with Irish and German Catholic neighbors, especially the Irish Catholics who controlled Democratic Party politics[39] at the time. Jews successfully established themselves in the garment trades and in the needle unions in New York. By the 1930s they were a major political factor in New York, with strong support for the most liberal programs of the New Deal. They continued as a major element of the New Deal Coalition, giving special support to the Civil Rights Movement. By the mid-1960s, however, the Black Power movement caused a growing separation between blacks and Jews, though both groups remained solidly in the Democratic camp.[40]

Earlier Jewish immigrants from Germany tended to be politically conservative, though many, including the devoutly Republican Louis Marshall, believed that Jews should not have a political direction at all.[41] Meanwhile, the wave of Jews from Eastern Europe starting in the early 1880s were generally more liberal or left-wing and became the political majority.[42] Many came to America with experience in the socialist, anarchist and communist movements as well as the Labor Bund, emanating from Eastern Europe. Many Jews rose to leadership positions in the early 20th century American labor movement and helped to found unions that played a major role in left-wing politics and, after 1936, in Democratic Party politics.[42]

American Jews generally leaned towards the Republican party in the second half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century. This was compounded by the strong Evangelical imagery used by William Jennings Bryan and other Populist Democrats, which caused fears of Antisemitism among American Jews. Additionally Republican candidates such as William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt were extremely popular with Jewish voters.[43] However, the majority of Jews have generally voted Democratic since at least 1916, when they voted 55% for Woodrow Wilson, and especially since 1928, when 72% supported the unsuccessful candidacy of Al Smith.[34]

With the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt, American Jews voted more solidly Democratic. They voted 90% for Roosevelt in the elections of 1940, and 1944, representing the highest of support, equaled only once since. In the election of 1948, Jewish support for Democrat Harry S. Truman dropped to 75%, with 15% supporting the new Progressive Party.[34] As a result of lobbying, and hoping to better compete for the Jewish vote, both major party platforms had included a pro-Zionist plank since 1944,[44][45] and supported the creation of a Jewish state; it had little apparent effect however, with 90% still voting other-than-Republican. In every election since, except for 1980, no Democratic presidential candidate has won with less than 67% of the Jewish vote. (In 1980, Carter obtained 45% of the Jewish vote. See below.)

During the 1952 and 1956 elections, Jewish voters cast 60% or more of their votes for Democrat Adlai Stevenson, while General Eisenhower garnered 40% of the Jewish vote for his reelection, the best showing to date for the Republicans since Warren G. Harding's 43% in 1920.[34] In 1960, 83% voted for Democrat John F. Kennedy against Richard Nixon, and in 1964, 90% of American Jews voted for Lyndon Johnson, over his Republican opponent, arch-conservative Barry Goldwater. Hubert Humphrey garnered 81% of the Jewish vote in the 1968 elections in his losing bid for president against Richard Nixon.[34]

During the Nixon re-election campaign of 1972, Jewish voters were apprehensive about George McGovern and only favored the Democrat by 65%, while Nixon more than doubled Republican Jewish support to 35%. In the election of 1976, Jewish voters supported Democrat Jimmy Carter by 71% over incumbent president Gerald Ford's 27%, but during the Carter re-election campaign of 1980, Jewish voters greatly abandoned the Democrat, with only 45% support, while Republican winner Ronald Reagan garnered 39%, and 14% went to independent (former Republican) John Anderson.[34][46]

During the Reagan re-election campaign of 1984, the Republican retained 31% of the Jewish vote, while 67% voted for Democrat Walter Mondale. The 1988 election saw Jewish voters favor Democrat Michael Dukakis by 64%, while George H. W. Bush polled a respectable 35%, but during Bush's re-election attempt in 1992, his Jewish support dropped to just 11%, with 80% voting for Bill Clinton and 9% going to independent Ross Perot. Clinton's re-election campaign in 1996 maintained high Jewish support at 78%, with 16% supporting Bob Dole and 3% for Perot.[34][46]

In the 2000 presidential election, Joe Lieberman became the first American Jew to run for national office on a major-party ticket when he was chosen as Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore's vice-presidential nominee. The elections of 2000 and 2004 saw continued Jewish support for Democrats Al Gore and John Kerry, a Catholic, remain in the high- to mid-70% range, while Republican George W. Bush's re-election in 2004 saw Jewish support rise from 19% to 24%.[46][47]

In the 2008 presidential election, 78% of Jews voted for Barack Obama, who became the first African American to be elected president.[48] Additionally, 83% of white Jews voted for Obama compared to just 34% of white Protestants and 47% of white Catholics, though 67% of those identifying with another religion and 71% identifying with no religion also voted Obama.[49]

In the February 2016 New Hampshire Democratic Primary, Bernie Sanders became the first Jewish candidate to win a state's presidential primary election.[50]

For congressional and senate races, since 1968, American Jews have voted about 70–80% for Democrats;[51] this support increased to 87% for Democratic House candidates during the 2006 elections.[52]

The first American Jew to serve in the Senate was David Levy Yulee, who was Florida's first Senator, serving 1845–1851 and again 1855–1861.

There were 19 Jews among the 435 US Representatives at the start of the 112th Congress;[53] 26 Democrats and 1 (Eric Cantor) Republican. While many of these Members represented coastal cities and suburbs with significant Jewish populations, others did not (for instance, Kim Schrier of Seattle, Washington; John Yarmuth of Louisville, Kentucky; and David Kustoff and Steve Cohen of Memphis, Tennessee). The total number of Jews serving in the House of Representatives declined from 31 in the 111th Congress.[54] John Adler of New Jersey, Steve Kagan of Wisconsin, Alan Grayson of Florida, and Ron Klein of Florida all lost their re-election bids, Rahm Emanuel resigned to become the President's Chief of Staff; and Paul Hodes of New Hampshire did not run for re-election but instead (unsuccessfully) sought his state's open Senate seat. David Cicilline of Rhode Island was the only Jewish American who was newly elected to the 112th Congress; he had been the Mayor of Providence. The number declined when Jane Harman, Anthony Weiner, and Gabby Giffords resigned during the 112th Congress.[citation needed]

As of January 2014[update], there were five openly gay men serving in Congress, and two are Jewish: Jared Polis of Colorado and David Cicilline of Rhode Island.[citation needed]

In November 2008, Cantor was elected as the House Minority Whip, the first Jewish Republican to be selected for the position.[55] In 2011, he became the first Jewish House Majority Leader. He served as Majority Leader until 2014, when he resigned shortly after his loss in the Republican primary election for his House seat.[citation needed]

In 2013, Pew found that 70% of American Jews identified with or leaned toward the Democratic Party, with just 22% identifying with or leaning toward the Republican Party.[56]

The 114th Congress included 10 Jews[57] among 100 U.S. Senators: nine Democrats (Michael Bennet, Richard Blumenthal, Brian Schatz, Benjamin Cardin, Dianne Feinstein, Jon Ossoff, Jacky Rosen, Charles Schumer, Ron Wyden), and Bernie Sanders, who became a Democrat to run for President but returned to the Senate as an Independent.[58]

In the 118th Congress, there are 28 Jewish US Representatives.[59] 25 are Democrats and the other 3 are Republicans. All 10 Jewish Senators are Democrats.[60]

Additionally, six members of President Joe Biden's cabinet were Jewish (Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Attorney General Merrick Garland, DNI Avril Haines, White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen).[61]

Participation in civil rights movements

[edit]Members of the American Jewish community have included prominent participants in civil rights movements. In the mid-20th century, there were American Jews who were among the most active participants in the Civil Rights Movement and feminist movements. A number of American Jews have also been active figures in the struggle for gay rights in America.

Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, stated the following when he spoke from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial during the famous March on Washington on August 28, 1963: "As Jews we bring to this great demonstration, in which thousands of us proudly participate, a twofold experience—one of the spirit and one of our history. ... From our Jewish historic experience of three and a half thousand years we say: Our ancient history began with slavery and the yearning for freedom. During the Middle Ages my people lived for a thousand years in the ghettos of Europe. ... It is for these reasons that it is not merely sympathy and compassion for the black people of America that motivates us. It is, above all and beyond all such sympathies and emotions, a sense of complete identification and solidarity born of our own painful historic experience."[62][63]

The Holocaust

[edit]During the World War II period, the American Jewish community was bitterly and deeply divided and as a result, it was unable to form a united front. Most Jews who had previously emigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe supported Zionism, because they believed that a return to their ancestral homeland was the only solution to the persecution and the genocide which were then occurring across Europe. One important development was the sudden conversion of many American Jewish leaders to Zionism late in the war.[64] The Holocaust was largely ignored by American media as it was happening. Reporters and editors largely did not believe the stories of atrocities which were coming out of Europe.[65]

The Holocaust had a profound impact on the Jewish community in the United States, especially after 1960 as Holocaust education improved, as Jews tried to comprehend what had happened during it, and especially as they tried to commemorate it and grapple with it when they looked to the future. Abraham Joshua Heschel summarized this dilemma when he attempted to understand Auschwitz: "To try to answer is to commit a supreme blasphemy. Israel enables us to bear the agony of Auschwitz without radical despair, to sense a ray [of] God's radiance in the jungles of history."[66]

International affairs

[edit]

Zionism became a well-organized movement in the U.S. with the involvement of leaders such as Louis Brandeis and the promise of a reconstituted homeland in the Balfour Declaration.[67] Jewish Americans organized large-scale boycotts of German merchandise during the 1930s to protest Nazi Germany. Franklin D. Roosevelt's leftist domestic policies received strong Jewish support in the 1930s and 1940s, as did his anti-Nazi foreign policy and his promotion of the United Nations. Support for political Zionism in this period, although growing in influence, remained a distinctly minority opinion among Jews in the United States until about 1944–45, when the early rumors and reports of the systematic mass murder of the Jews in Nazi-occupied countries became publicly known with the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps. The founding of the modern State of Israel in 1948 and recognition thereof by the American government[68][69] (following objections by American isolationists) was an indication of both its intrinsic support and its response to learning the horrors of the Holocaust.

This attention was based on a natural affinity toward and support for Israel in the Jewish community. The attention is also because of the ensuing and unresolved conflicts regarding the founding of Israel and the role for the Zionist movement going forward. A lively internal debate commenced, following the Six-Day War. The American Jewish community was divided over whether or not they agreed with the Israeli response; the great majority came to accept the war as necessary.[70] Similar tensions were aroused by the 1977 election of Menachem Begin and the rise of Revisionist policies, the 1982 Lebanon War and the continuing administrative governance of portions of the West Bank territory.[71] Disagreement over Israel's 1993 acceptance of the Oslo Accords caused a further split among American Jews;[72] this mirrored a similar split among Israelis and led to a parallel rift within the pro-Israel lobby, and even ultimately to the United States for its "blind" support of Israel.[72] Abandoning any pretense of unity, both segments began to develop separate advocacy and lobbying organizations. The liberal supporters of the Oslo Accord worked through Americans for Peace Now (APN), Israel Policy Forum (IPF) and other groups friendly to the Labour government in Israel. They tried to assure Congress that American Jewry was behind the Accord and defended the efforts of the administration to help the fledgling Palestinian Authority (PA), including promises of financial aid. In a battle for public opinion, IPF commissioned a number of polls showing widespread support for Oslo among the community.

In opposition to Oslo, an alliance of conservative groups, such as the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA), Americans For a Safe Israel (AFSI), and the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs (JINSA) tried to counterbalance the power of the liberal Jews. On October 10, 1993, the opponents of the Palestinian-Israeli accord organized at the American Leadership Conference for a Safe Israel, where they warned that Israel was prostrating itself before "an armed thug", and predicted and that the "thirteenth of September is a date that will live in infamy". Some Zionists also criticized, often in harsh language, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres, his foreign minister and chief architect of the peace accord. With the community so strongly divided, AIPAC and the Presidents Conference, which was tasked with representing the national Jewish consensus, struggled to keep the increasingly antagonistic discourse civil. Reflecting these tensions, Abraham Foxman from the Anti-Defamation League was asked by the conference to apologize for criticizing ZOA's Morton Klein. The conference, which under its organizational guidelines was in charge of moderating communal discourse, reluctantly censured some Orthodox spokespeople for attacking Colette Avital, the Labor-appointed Israeli Consul General in New York and an ardent supporter of that version of a peace process.[73]

Demographics

[edit]

As of 2020, the American Jewish population is, depending on the method of identification, either the largest in the world, or the second-largest in the world (after Israel). Precise population figures vary depending on whether Jews are accounted for based on halakhic considerations, or secular, political and ancestral identification factors. There were about four million adherents of Judaism in the US as of 2001, approximately 1.4% of the US population. According to the Jewish Agency, for the year 2023 Israel was home to 7.2 million Jews (46% of the world's Jewish population), while the United States contained 6.3 million (40.1%).[74]

According to Gallup and Pew Research Center findings, "at maximum 2.2% of the US adult population has some basis for Jewish self-identification."[75] In 2020, the demographers Arnold Dashefsky and Ira M. Sheskin estimated in the American Jewish Yearbook that the American Jewish population totaled 7.15 million, making up 2.17% of the country's 329.5 million inhabitants.[76][77] In the same year, the American Jewish population was estimated at 7.6 million people, accounting for 2.4% of the total US population, by other organization. This includes 4.9 million adults who identify their religion as Jewish, 1.2 million Jewish adults who identify with no religion, and 1.6 million Jewish children.[78]

According to a 2020 study by the Pew Research Center, the core American Jewish population is estimated at 7.5 million people, this includes 5.8 million Jewish adults.[79] The study found that the median age of the American Jewish population is 49, and around 18% of American Jewish are under the age of 30, while 49% of American Jewish are ages 50 and older.[80] The study found also that 9% of American Jewish identify as LGBT.[81]

The American Jewish Yearbook population survey had placed the number of American Jews at 6.4 million, or approximately 2.1% of the total population. This figure is significantly higher than the previous large scale survey estimate, conducted by the 2000–2001 National Jewish Population estimates, which estimated 5.2 million Jews. A 2007 study released by the Steinhardt Social Research Institute (SSRI) at Brandeis University presents evidence to suggest that both these figures may be underestimations with a potential 7.0–7.4 million Americans of Jewish descent.[82] Those higher estimates were however arrived at by including all non-Jewish family members and household members, rather than surveyed individuals.[83] In a 2019 study by Jews of Color Initiative it was found that approximately 12-15% of Jews in the United States, about 1,000,000 of 7,200,000 identify as multiracial and Jews of color.[84][85][86][87][88]

The overall population of Americans of Jewish descent is demographically characterized by an aging population composition and low fertility rates significantly below generational replacement.[83] However, the Orthodox Jewish population, concentrated in the Northeastern United States, has fertility rates when taken alone which are significantly higher than both generational replacement and that of the average U.S. population.

The National Jewish Population Survey of 1990 asked 4.5 million adult Jews to identify their denomination. The national total showed 38% were affiliated with the Reform tradition, 35% were Conservative, 6% were Orthodox, 1% were Reconstructionists, 10% linked themselves to some other tradition, and 10% said they are "just Jewish."[89] In 2013, Pew Research's Jewish population survey found that 35% of American Jews identified as Reform, 18% as Conservative, 10% as Orthodox, 6% who identified with other sects, and 30% did not identify with a denomination.[90] Pew's 2020 poll found that 37% affiliated with Reform Judaism, 17% with Conservative Judaism, and 9% with Orthodox Judaism. Young Jews are more likely to identify as Orthodox or as unaffiliated compared to older members of the Jewish community.[6]

Many Jews are concentrated in the Northeastern United States, particularly around New York City. The world's largest menorah is lit annually at Grand Army Plaza in Manhattan, while the largest menorah in New Jersey is similarly celebrated in Monroe Township, Middlesex County. Many Jews also live in South Florida, Los Angeles, and other large metropolitan areas, like Chicago, San Francisco, or Atlanta. The metropolitan areas of New York City, Los Angeles, and Miami contain nearly one quarter of the world's Jews[91] and the New York City metropolitan area itself contains around a quarter of all Jews living in the United States.

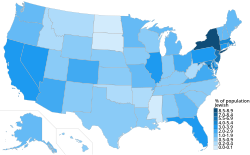

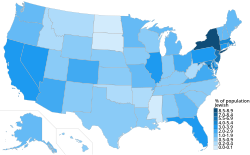

By state

[edit]According to a study published by demographers and sociologists Ira M. Sheskin and Arnold Dashefsky in the American Jewish Yearbook, the distribution of the Jewish population in 2024 was as follows:[92]

| State | Jewish Population (2024) | Percent Jewish | |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | 57,300 | 8.44% | |

| 1 | 1,672,025 | 8.54% | |

| 2 | 581,200 | 6.26% | |

| 3 | 318,450 | 4.55% | |

| 4 | 250,860 | 4.06% | |

| 5 | 141,500 | 3.91% | |

| 6 | 753,865 | 3.33% | |

| 7 | 1,259,315 | 3.23% | |

| 8 | 347,850 | 2.68% | |

| 9 | 85,330 | 2.67% | |

| 10 | 334,180 | 2.66% | |

| 11 | 117,900 | 2.01% | |

| 12 | 12,700 | 1.96% | |

| 13 | 165,260 | 1.90% | |

| 14 | 132,360 | 1.78% | |

| 15 | 18,950 | 1.73% | |

| 16 | 17,400 | 1.69% | |

| 17 | 70,105 | 1.66% | |

| 18 | 177,295 | 1.50% | |

| 19 | 20,900 | 1.49% | |

| 20 | 148,555 | 1.35% | |

| 21 | 18,460 | 1.32% | |

| 22 | 129,225 | 1.29% | |

| 23 | 68,855 | 1.20% | |

| 24 | 71,840 | 1.16% | |

| 25 | 88,530 | 1.13% | |

| 26 | 19,855 | 0.94% | |

| 27 | 99,795 | 0.92% | |

| 28 | 6,510 | 0.89% | |

| 29 | 48,515 | 0.82% | |

| 30 | 220,685 | 0.72% | |

| 31 | 9,900 | 0.69% | |

| 32 | 36,210 | 0.67% | |

| 33 | 17,590 | 0.60% | |

| 34 | 10,230 | 0.52% | |

| 35 | 19,870 | 0.43% | |

| 36 | 29,775 | 0.42% | |

| 37 | 31,205 | 0.40% | |

| 38 | 18,225 | 0.40% | |

| 39 | 13,030 | 0.38% | |

| 40 | 2,210 | 0.38% | |

| 41 | 18,080 | 0.35% | |

| 42 | 5,920 | 0.30% | |

| 43 | 3,170 | 0.28% | |

| 44 | 8,880 | 0.22% | |

| 45 | 6,385 | 0.20% | |

| 46 | 5,090 | 0.17% | |

| 47 | 2,940 | 0.17% | |

| 48 | 910 | 0.12% | |

| 49 | 2,885 | 0.10% | |

| 50 | 765 | 0.08% | |

| Total | 7,698,840 | 2.30% |

Significant Jewish population centers

[edit]| Rank | Metro area | Number of Jews | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (WJC)[91] | (ARDA)[93] | (WJC) | (ASARB) | |

| 1 | 1 | New York City | 1,750,000 | 2,028,200 |

| 2 | 3 | Miami | 535,000 | 337,000 |

| 3 | 2 | Los Angeles | 490,000 | 662,450 |

| 4 | 4 | Philadelphia | 254,000 | 285,950 |

| 5 | 6 | Chicago | 248,000 | 265,400 |

| 8 | 8 | San Francisco Bay Area | 210,000 | 218,700 |

| 6 | 7 | Boston | 208,000 | 261,100 |

| 8 | 5 | Baltimore–Washington | 165,000 | 276,445 |

| Rank | State | Percent Jewish |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | New York | 8.91 |

| 2 | New Jersey | 5.86 |

| 3 | District of Columbia | 4.25 |

| 4 | Massachusetts | 4.07 |

| 5 | Maryland | 3.99 |

| 6 | Florida | 3.28 |

| 7 | Connecticut | 3.28 |

| 8 | California | 3.18 |

| 9 | Nevada | 2.69 |

| 10 | Illinois | 2.31 |

| 11 | Pennsylvania | 2.29 |

The New York City metropolitan area is the second-largest Jewish population center in the world after the Tel Aviv metropolitan area in Israel.[91] Several other major cities have large Jewish communities, including Los Angeles, Miami, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco and Philadelphia.[94] In many metropolitan areas, the majority of Jewish families live in suburban areas. The Greater Phoenix area was home to about 83,000 Jews in 2002, and has been rapidly growing.[95] The greatest Jewish population on a per-capita basis for incorporated areas in the US are Kiryas Joel Village, New York (greater than 93% based on language spoken in home),[96] City of Beverly Hills, California (61%),[97] and Lakewood Township, New Jersey (59%),[98] with two of the incorporated areas, Kiryas Joel and Lakewood, having a high concentration of Haredi Jews, and one incorporated area, Beverly Hills, having a high concentration of non-Orthodox Jews.

The phenomenon of Israeli migration to the US is often termed Yerida. The Israeli immigrant community in America is less widespread. The significant Israeli immigrant communities in the United States are in the New York City metropolitan area, Los Angeles, Miami, and Chicago.[99]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development calculated an 'expatriate rate' of 2.9 persons per thousand, putting Israel in the mid-range of expatriate rates among the 175 OECD countries examined in 2005.[100]

According to the 2001 undertaking[101] of the National Jewish Population Survey, 4.3 million American Jews have some sort of strong connection to the Jewish community, whether religious or cultural.

Distribution of Jewish Americans

[edit]According to the North American Jewish Data Bank[102] the 104 counties and independent cities as of 2011[update] with the largest Jewish communities, as a percentage of population, were:

Assimilation and population changes

[edit]These parallel themes have facilitated the extraordinary economic, political, and social success of the American Jewish community, but also have contributed to widespread cultural assimilation.[103] More recently however, the propriety and degree of assimilation has also become a significant and controversial issue within the modern American Jewish community, with both political and religious skeptics.[104]

While not all Jews disapprove of intermarriage, many members of the Jewish community have become concerned that the high rate of interfaith marriage will result in the eventual disappearance of the American Jewish community. Intermarriage rates have risen from roughly 6% in 1950 and 25% in 1974,[105] to approximately 40–50% in the year 2000.[106] By 2013, the intermarriage rate had risen to 71% for non-Orthodox Jews.[107] This, in combination with the comparatively low birthrate in the Jewish community, has led to a 5% decline in the Jewish population of the United States in the 1990s. In addition to this, when compared with the general American population, the American Jewish community is slightly older.

A third of intermarried couples provide their children with a Jewish upbringing, and doing so is more common among intermarried families raising their children in areas with high Jewish populations.[108] The Boston area, for example, is exceptional in that an estimated 60% of children of intermarriages are being raised Jewish, meaning that intermarriage would actually be contributing to a net increase in the number of Jews.[109] As well, some children raised through intermarriage rediscover and embrace their Jewish roots when they themselves marry and have children.

In contrast to the ongoing trends of assimilation, some communities within American Jewry, such as Orthodox Jews, have significantly higher birth rates and lower intermarriage rates, and are growing rapidly. The proportion of Jewish synagogue members who were Orthodox rose from 11% in 1971 to 21% in 2000, while the overall Jewish community declined in number. [110] In 2000, there were 360,000 so-called "ultra-orthodox" (Haredi) Jews in USA (7.2%).[111] The figure for 2006 is estimated at 468,000 (9.4%).[111] Data from the Pew Center shows that, as of 2013, 27% of American Jews under the age of 18 live in Orthodox households, a dramatic increase from Jews aged 18 to 29, only 11% of whom are Orthodox. The UJA-Federation of New York reports that 60% of Jewish children in the New York City area live in Orthodox homes. In addition to economizing and sharing, many Haredi communities depend on government aid to support their high birth rate and large families. The Hasidic village of New Square, New York receives Section 8 housing subsidies at a higher rate than the rest of the region, and half of the population in the Hasidic village of Kiryas Joel, New York receive food stamps, while a third receive Medicaid.[112]

About half of the American Jews are considered to be religious. Out of this 2,831,000 religious Jewish population, 92% are non-Hispanic white, 5% Hispanic (Most commonly from Argentina, Venezuela, or Cuba), 1% Asian, 1% black and 1% Other (mixed-race etc.). Almost this many non-religious Jews exist in the United States.[113]

Race and ethnicity

[edit]

The United States Census Bureau classifies most American Jews as white.[114] Jewish people are culturally diverse and may be of any race, ethnicity, or national origin. Many Jews have culturally assimilated into and are phenotypically indistinguishable from the dominant local populations of regions like Europe, the Caucasus and the Crimea, North Africa, West Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, South, East, and Central Asia, and the Americas where they have lived for many centuries.[115][116][117] Most American Jews are Ashkenazi Jews who descend from Jewish populations of Central and Eastern Europe and are considered white unless they are Ashkenazi Jews of color.[citation needed] Many American Jews identify themselves as being both Jewish and white, while many solely identify as Jewish, resisting this identification.[118] Several commentators have observed that "many American Jews retain a feeling of ambivalence about whiteness".[119] Karen Brodkin explains this ambivalence as rooted in anxieties about the potential loss of Jewish identity, especially outside of intellectual elites.[120] Similarly, Kenneth Marcus observes a number of ambivalent cultural phenomena which have also been noted by other scholars, and he concludes that "the veneer of whiteness has not established conclusively the racial construction of American Jews".[121] The relationship between Jewish identity and white majority identity continues to be described as "complicated" for many American Jews, particularly Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews of European descent. The issue of Jewish whiteness may be different for many Mizrahi, Sephardi, Black, Asian, and Latino Jews, many of whom may never be considered white by society.[122] Many American white nationalists and white supremacists view all Jews as non-white, even if they are of European descent.[123] Some white nationalists believe that Jews can be white and a small number of white nationalists are Jewish.[124]

In 2013, the Pew Research Center's Portrait of Jewish Americans found that more than 90% of Jews who responded to its survey described themselves as being non-Hispanic whites, 2% described themselves as being black, 3% described themselves as being Hispanic, and 2% described themselves as having other racial or ethnic backgrounds.[125]

Jews by race, ancestry, or national origin

[edit]Asian American Jews

[edit]According to the Pew Research Center, fewer than 1% of American Jews in 2020 identified as Asian Americans. Around 1% of religious Jews identified as Asian American.[126]

A small but growing community of around 350 Indian American Jews lives in the New York City metropolitan area, in both New York state and New Jersey. Many are members of India's Bene Israel community.[127] The Indian Jewish Congregation of USA, headquartered in New York City, is the center of the organized community.[128]

Jews of European descent

[edit]Jews of European descent, often referred to as white Jews, are classified as white by the US census and have generally been classified as legally white throughout American history.[129] Many American Jews of European descent identify themselves as being both Jewish and white, while others solely identify themselves as being Jewish or identify as both Jewish and non-white.[130] However, Jews of European descent rarely identify as Jews of color and are rarely considered people of color in American society. According to the Pew Research Center, the majority of American Jews are non-Hispanic white Ashkenazi Jews.[126] Law professor David Bernstein has questioned the idea that American Jews were once considered non-white, writing that American Jews were "indeed considered white by law and by custom" despite the fact that they experienced "discrimination, hostility, assertions of inferiority and occasionally even violence." Bernstein notes that Jews were not targeted by laws against interracial marriage, were allowed to attend whites-only schools, and were classified as white in the Jim Crow South.[131] The sociologists Philip Q. Yang and Kavitha Koshy have also questioned what they call the "becoming white thesis", noting that most Jews of European descent have been legally classified as white since the first US census in 1790, were legally white for the purposes of the Naturalization Act of 1790 that limited citizenship to "free White person(s)", and that they could find no legislative or judicial evidence that American Jews had ever been considered non-white.[129]

Several commentators have observed that "many American Jews retain a feeling of ambivalence about whiteness".[132] Karen Brodkin explains this ambivalence as rooted in anxieties about the potential loss of Jewish identity, especially outside of intellectual elites.[133] Similarly, Kenneth Marcus observes a number of ambivalent cultural phenomena which have also been noted by other scholars, and he concludes that "the veneer of whiteness has not established conclusively the racial construction of American Jews".[134] The relationship between American Jews and white majority identity continues to be described as "complicated".[135] Many American white nationalists view Jews as non-white.[136]

Jews of Middle Eastern and North African descent

[edit]Jews of Middle Eastern and North African descent (often referred to as Mizrahi Jews) are classified as white by the US census. Mizrahi Jews sometimes identify as Jews of color, but often do not, and they may or may not be considered people of color by society. Syrian Jews rarely identify as Jews of color and are generally not considered Jews of color by society. Many Syrian Jews identify as white, Middle Eastern, or otherwise non-white rather than as Jews of color.[126]

African American Jews

[edit]The American Jewish community includes African American Jews and other American Jews who are of African descent, a definition which excludes North African Jewish Americans, who are currently classified by the US census as being white (although a new category was recommended by the Census Bureau for the 2020 census).[137] Estimates of the number of American Jews of African descent in the United States range from 20,000[138] to 200,000.[139] Jews of African descent belong to all American Jewish denominations. Like their other Jewish counterparts, some black Jews are atheists.

Notable African American Jews include Drake, Lenny Kravitz, Lisa Bonet, Sammy Davis Jr., Rashida Jones, Ros Gold-Onwude, Yaphet Kotto, Jordan Farmar, Taylor Mays, Daveed Diggs, Alicia Garza, Tiffany Haddish, and rabbis Capers Funnye and Alysa Stanton.

Relations between American Jews of African descent and other Jewish Americans are generally cordial.[citation needed] There are, however, disagreements with a specific minority of Black Hebrew Israelites community from among African Americans who consider themselves, but not other Jews, to be the true descendants of the ancient Israelites. Black Hebrew Israelites are generally not considered members of the mainstream Jewish community, because they have not formally converted to Judaism, and they are not ethnically related to other Jews. One such group, the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem, emigrated to Israel and was granted permanent residency status there.[140]

Hispanic and Latin American Jews

[edit]Hispanic Jews have lived in what is now the United States since colonial times. The earliest Hispanic Jewish settlers were Sephardi Jews from Spain and Portugal. Beginning in the 1500s, some of the Spanish settlers in what is now New Mexico and Texas were Crypto-Jews, but there was no organized Jewish presence.[141][142] Later waves of Sephardi immigration brought Judeo-Spanish speaking Jews from the Ottoman Empire, in what is now Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Libya, and Syria. These Spanish-speaking Sephardi Jews, as well as Sephardi Jews of European descent, such as the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, are sometimes considered culturally but not ethnically Hispanic.

Hispanic and Latin American Jews, particularly Hispanic and Latin American Ashkenazi Jews, often identify as white rather than as Jews of color. Some Jews with roots in Latin America may not identify as "Hispanic" or "Latino" at all, usually due to their recent European immigrant origins.[126] American Jews of Argentine, Brazilian, and Mexican descent are often Ashkenazi, but some are Sephardi.[143]

Jews divided by cultural or Jewish ethnic division groupings

[edit]| Ancestry | Population | % of US population |

|---|---|---|

| Ashkenazim[144] | 5,000,000–6,000,000 | 1.8–2.1% |

| Sephardim[145] | 300,000 | 0.086–0.086% |

| Mizrahim | 250,000 | 0.072–0.072% |

| Italkim[citation needed] | 200,000 | 0.057–0.057% |

| Bukharim | 50,000–60,000 | 0.014–0.017% |

| Juhurim | 10,000–40,000 | 0.003–0.011% |

| Turkos | 8,000 | 0.002–0.002% |

| Romanyotim | 6,500 | 0.002–0.002% |

| Beta Israel[146] | 1,000 | 0.0003% |

| Total[147] | 5,700,000–8,000,000 | 1.6–2.3% |

A majority of the Jewish population in the United States are Ashkenazi Jews who descend from diaspora Jewish populations of Central and Eastern Europe. Most American Ashkenazi Jews are non-Hispanic whites, but a minority are Jews of color, Hispanic/Latino, or both.

Largely expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in the late 15th century, Sephardi Jews carried a distinctive Jewish diasporic identity with them to the Americas (although in smaller numbers compared to the Ashkenazi Jewish diaspora) and all other places of their exiled settlement. They sometimes settled near existing Jewish communities, such as the one from former Kurdistan, or were the first in new frontiers, with their furthest reach via the Silk Road.[148] As a result of the more recent Jewish exodus from Arab lands, many of the Sephardim Tehorim from Western Asia and North Africa relocated to either Israel or France, where they form a significant portion of the Jewish communities today. Other significant communities of Sephardim Tehorim also migrated in more recent times from the Near East to New York City, Argentina, Costa Rica, Mexico, Montreal, Gibraltar, Puerto Rico, and Dominican Republic.[149] Because of poverty and turmoil in Latin America, another wave of Sephardic Jews joined other Latin Americans who migrated to the United States, Canada, Spain, and other countries of Europe.

Post-1948, Mizrahi Jewish, mostly thousands from Lebanese, Syrian and Egyptian Jewish descent, as well as some from other Middle East and North African Jewish communities migrated to the United States.

Since the 1990s, around 1000 Hebrew-speaking, Ethiopian Jews that had settled in Israel as Ethiopian Jews in Israel re-settled in the United States as Ethiopian Americans, with around half of the Ethiopian Jewish Israeli-American community living in New York.[150]

Socioeconomics

[edit]Education plays a major role as a part of Jewish identity. As Jewish culture puts a special premium on it and stresses the importance of cultivation of intellectual pursuits, scholarship, and learning, American Jews as a group tend to be better educated and earn more than Americans as a whole.[151][152][153][154] Jewish Americans also have an average of 14.7 years of schooling making them the most highly educated of all major religious groups in the United States.[155][156]

Forty-four percent (55% of Reform Jews) report family incomes of over $100,000 compared to 19% of all Americans, with the next highest group being Hindus at 43%.[157][158] And while 27% of Americans have a four-year university or postgraduate education, fifty-nine percent (66% of Reform Jews) of American Jews have, the second highest of any ethnic groups after Indian-Americans.[157][159][160] 75% of American Jews have achieved some form of post-secondary education if two-year vocational and community college diplomas and certificates are also included.[161][162][163][156]

31% of American Jews hold a graduate degree; this figure is compared with the general American population where 11% of Americans hold a graduate degree.[157] White collar professional jobs have been attractive to Jews and much of the community tend to take up professional white collar careers requiring tertiary education involving formal credentials where the respectability and reputability of professional jobs is highly prized within Jewish culture. While 46% of Americans work in professional and managerial jobs, 61% of American Jews work as professionals, many of whom are highly educated, salaried professionals whose work is largely self-directed in management, professional, and related occupations such as engineering, science, medicine, investment banking, finance, law, and academia.[164]

Much of the Jewish American community lead middle class lifestyles.[165] While the median household net worth of the typical American family is $99,500, among American Jews the figure is $443,000.[166][167] In addition, the median Jewish American income is estimated to be in the range of $97,000 to $98,000, nearly twice as high the American national median.[168] Either of these two statistics may be confounded by the fact that the Jewish population is on average older than other religious groups in the country, with 51% of polled adults over the age of 50 compared to 41% nationally.[159] Older people tend to both have higher income and be more highly educated. By 2016, Modern Orthodox Jews had a median household income of $158,000, while Open Orthodox Jews had a median household income at $185,000 (compared to the American median household income of $59,000 for 2016).[169]

According to a 2020 study by the Pew Research Center, 23% of American Jewish living in households with incomes of at least $200,000. Conservatives (27%) and Reforms (26%) are more likely to live in households with incomes of at least $200,000 than those who are Orthodox (16%).[170] The study found also that American Jews are a comparatively well-educated group, around 60% of them are college graduates. Reforms (64%) and Conservatives (55%) are more likely to obtain college or postgraduate education than those who are Orthodox (37%).[171]

As a whole, American and Canadian Jews donate more than $9 billion a year to charity. This reflects Jewish traditions of supporting social services as a way of living out the dictates of Jewish law. Most of the charities that benefit are not specifically Jewish organizations.[172]

While the median income of Jewish Americans is high, some Jewish communities have high levels of poverty. In the New York area, there are approximately 560,000 Jews living in poor or near-poor households, representing about 20% of the New York metropolitan Jewish community. Jewish people affected by poverty are disproportionately likely to be children, young adults, the elderly, people with low educational attainment, part-time workers, immigrants from the former Soviet Union, immigrants without American citizenship, Holocaust survivors, Orthodox families, and single adults including single parents.[173] Disability is a major factor in the socioeconomic status of disabled Jews. Disabled Jews are significantly more likely to be low-income compared to able-bodied Jews, while high-income Jews are significantly less likely to be disabled.[174][175] Secular Jews, Jews of no denomination, and people who identify as "just Jewish" are also more likely to live in poverty compared to Jews affiliated with a religious denomination.[176]

According to analysis by Gallup, American Jews have the highest well-being of any ethnic or religious group in America.[177][178]

The great majority of school-age Jewish students attend public schools, although Jewish day schools and yeshivas are to be found throughout the country. Jewish cultural studies and Hebrew language instruction is also commonly offered at synagogues in the form of supplementary Hebrew schools or Sunday schools.

From the early 1900s until the 1950s, quota systems were imposed at elite colleges and universities particularly in the Northeast, as a response to the growing number of children of recent Jewish immigrants; these limited the number of Jewish students accepted, and greatly reduced their previous attendance. Jewish enrollment at Cornell's School of Medicine fell from 40% to 4% between the world wars, and Harvard's fell from 30% to 4%.[179] Before 1945, only a few Jewish professors were permitted as instructors at elite universities. In 1941, for example, antisemitism drove Milton Friedman from a non-tenured assistant professorship at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[180] Harry Levin became the first Jewish full professor in the Harvard English department in 1943, but the Economics department decided not to hire Paul Samuelson in 1948. Harvard hired its first Jewish biochemists in 1954.[181]

According to Clark Kerr, Martin Meyerson in 1965 became the first Jew to serve, albeit temporarily, as the leader of a major American research university.[182] That year, Meyerson served as acting chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley, but was unable to obtain a permanent appointment as a result of a combination of tactical errors on his part and antisemitism on the UC Board of Regents.[182] Meyerson served as the president of the University of Pennsylvania from 1970 to 1981.

By 1986, a third of the presidents of the elite undergraduate final clubs at Harvard were Jewish.[180] Rick Levin was president of Yale University from 1993 to 2013, Judith Rodin was president of the University of Pennsylvania from 1994 to 2004 (and is currently president of the Rockefeller Foundation), Paul Samuelson's nephew, Lawrence Summers, was president of Harvard University from 2001 until 2006, and Harold Shapiro was president of Princeton University from 1992 until 2000.

American Jews at American higher education institutions

[edit]Public universities[183]

|

Private universities

|

Religion

[edit]

Observances and engagement

[edit]The American Jews' majority continues to identify themselves with Judaism and its main traditions, such as Conservative, Orthodox and Reform Judaism.[187][188] But, already in the 1980s, 20–30 percent of members of largest Jewish communities, such as of New York City, Chicago, Miami, and others, rejected a denominational label.[187]

According to the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey, 38% of Jews were affiliated with the Reform tradition, 35% were Conservative, 6% were Orthodox, 1% were Reconstructionists, 10% linked themselves to some other tradition, and 10% said they are "just Jewish".[189]

Jewish religious practice in America is quite varied. Among the 4.3 million American Jews described as "strongly connected" to Judaism, over 80% report some sort of active engagement with Judaism,[190] ranging from attending at daily prayer services on one end of the spectrum, to as little as attending only Passover Seders or lighting Hanukkah candles on the other.

According to a 2020 study by the Pew Research Center, 37% of American Jews identify as Reforms, 32% do not with a particular branch, 17% identify as Conservatives, 9% identify as Orthodox, and 4% are members of other Jewish branches, such as Reconstructionist or Humanist Judaism.[191] The survey found that Jews are far less religious than American adults as a whole, 8% of American Jews go to the synagogue at least once a month, 27% go few times a year, and 56% seldom or never go to the synagogue.[192]

A 2003 Harris Poll found that 16% of American Jews go to the synagogue at least once a month, 42% go less frequently but at least once a year, and 42% go less frequently than once a year.[193] The survey found that of the 4.3 million strongly connected Jews, 46% belong to a synagogue. Among those households who belong to a synagogue, 38% are members of Reform synagogues, 33% Conservative, 22% Orthodox, 2% Reconstructionist, and 5% other types.

Traditionally, Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews do not have different branches (Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, etc.) but usually remain observant and religious. However, their synagogues are generally considered Orthodox or Sephardic Haredim by non-Sephardic Jews. But, not all Sephardim are Orthodox; among the pioneers of Reform Judaism movement in the 1820s there was the Sephardic congregation Beth Elohim in Charleston, South Carolina.[194]

The survey discovered that Jews in the Northeast and Midwest are generally more observant than Jews in the South or West. Reflecting a trend also observed among other religious groups, Jews in the Northwestern United States are typically the least observant.

The 2008 American Religious Identification Survey found that around 3.4 million American Jews call themselves religious—out of a general Jewish population of about 5.4 million. The number of Jews who identify themselves as only culturally Jewish has risen from 20% in 1990 to 37% in 2008, according to the study. In the same period, the number of all US adults who said they had no religion rose from 8% to 15%. Jews are more likely to be secular than Americans in general, the researchers said. About half of all US Jews—including those who consider themselves religiously observant—claim in the survey that they have a secular worldview and see no contradiction between that outlook and their faith, according to the study's authors. Researchers attribute the trends among American Jews to the high rate of intermarriage and "disaffection from Judaism" in the United States.[195]

Religious beliefs

[edit]American Jews are more likely to be atheists or agnostics than most Americans, especially when they are compared with American Protestants or Catholics. A 2003 poll found that while 79% of Americans believe in God, only 48% of American Jews do, compared to 79% and 90% of American Catholics and Protestants respectively. While 66% of Americans said that they were "absolutely certain" of God's existence, 24% of American Jews said the same. And though 9% of Americans believe that there is no God (8% of American Catholics and 4% of American Protestants), 19% of American Jews believe that God does not exist.[193]

A 2009 Harris Poll showed that American Jews constitute the one religious group which is most accepting of the science of evolution, with 80% accepting evolution, compared to 51% for Catholics, 32% for Protestants, and 16% of born-again Christians.[196] They were also less likely to believe in supernatural phenomena such as miracles, angels, or heaven.

Christianity

[edit]A 2013 Pew Research Center report found that 1.7 million American Jewish adults, 1.6 million of whom were raised in Jewish homes or had Jewish ancestry, identified as Christians or Messianic Jews but also consider themselves ethnically Jewish. Another 700,000 American Christian adults considered themselves "Jews by affinity" or "grafted-in" Jews.[197][198] According to a 2020 study by the Pew Research Center, 19% of those who say they were raised Jewish, consider themselves Christian.[199]

A 2025 Pew Research Center report found that 7% of American adults who identify ethnically as Jewish were raised as Christians. Additionally, among those who were raised as religious Jews rather than in a Christian environment, 2% now identify as Christian.[200]

Buddhism

[edit]Jewish Buddhists[201] are overrepresented among American Buddhists; this is specifically the case among those Jews whose parents are not Buddhist, and those Jews who are without a Buddhist heritage, with between one fifth[202] and 30% of all American Buddhists identifying as Jewish[203] though only 2% of Americans are Jewish. Nicknamed Jubus, an increasing[citation needed] number of American Jews have started to adopt Buddhist spiritual practices, while at the same time, they are continuing to identify with and practice Judaism. It may be the individual practices both Judaism and Buddhism.[201] Notable American Jewish Buddhists include: Robert Downey Jr.[204] Allen Ginsberg,[205] Linda Pritzker,[206] Jonathan F.P. Rose,[207] Goldie Hawn[208] and daughter Kate Hudson, Steven Seagal, Adam Yauch of the rap group The Beastie Boys, and Garry Shandling. Film makers the Coen Brothers have been influenced by Buddhism as well for a time.[209]

Islam

[edit]A 2025 Pew Research Center report revealed that 1% of American Jewish adults who were raised in Judaism later identified as Muslim.[200]

Contemporary politics

[edit]

Today, American Jews are a distinctive and influential group in the nation's politics. Jeffrey S. Helmreich writes that the ability of American Jews to effect this through political or financial clout is overestimated,[210] that the primary influence lies in the group's voting patterns.[46]

"Jews have devoted themselves to politics with almost religious fervor," writes Mitchell Bard, who adds that Jews have the highest percentage voter turnout of any ethnic group (84% reported being registered to vote[211]).

Though the majority (60–70%) of the country's Jews identify as Democratic, Jews span the political spectrum, with those at higher levels of observance being far more likely to vote Republican than their less observant and secular counterparts.[212]

Owing to high Democratic identification in the 2008 United States presidential election, 78% of Jews voted for Democrat Barack Obama versus 21% for Republican John McCain, despite Republican attempts to connect Obama to Muslim and pro-Palestinian causes.[213] It has been suggested that running mate Sarah Palin's conservative views on social issues may have nudged Jews away from the McCain–Palin ticket.[46][213] In the 2012 presidential election, 69% of Jews voted for the Democratic incumbent President Obama.[214]

In 2019, after the 2016 election of Donald Trump, poll data from the Jewish Electorate Institute showed that 73% of Jewish voters felt less secure as Jews than before, 71% disapproved of Trump's handling of antisemitism (54% strongly disapprove), 59% felt that he bears "at least some responsibility" for the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting and Poway synagogue shooting, and 38% were concerned that Trump was encouraging right-wing extremism. Views of the Democratic and Republican parties were milder: 28% were concerned that Republicans were making alliances with white nationalists and tolerating antisemitism within their ranks, while 27% were concerned that Democrats were tolerating antisemitism within their ranks.[215]

In the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election, 77% of American Jews voted for Joe Biden, while 22% voted for Donald Trump.[216] A similar trend emerged in the 2024 Presidential Election, where 78% of American Jews voted for Kamala Harris while 22% voted for Donald Trump.[217]

Foreign policy

[edit]American Jews have displayed a very strong interest in foreign affairs, especially regarding Germany in the 1930s, and Israel since 1945.[218] Both major parties have made strong commitments in support of Israel. Dr. Eric Uslaner of the University of Maryland argues, with regard to the 2004 election: "Only 15% of Jews said that Israel was a key voting issue. Among those voters, 55% voted for Kerry (compared to 83% of Jewish voters not concerned with Israel)." Uslander goes on to point out that negative views of Evangelical Christians had a distinctly negative impact for Republicans among Jewish voters, while Orthodox Jews, traditionally more conservative in outlook as to social issues, favored the Republican Party.[219] A New York Times article suggests that the Jewish movement to the Republican party is focused heavily on faith-based issues, similar to the Catholic vote, which is credited for helping President Bush taking Florida in 2004.[220] However, Natan Guttman, The Forward's Washington bureau chief, dismisses this notion, writing in Moment that while "[i]t is true that Republicans are making small and steady strides into the Jewish community ... a look at the past three decades of exit polls, which are more reliable than pre-election polls, and the numbers are clear: Jews vote overwhelmingly Democratic,"[221] an assertion confirmed by the most recent presidential election results.

Jewish Americans were more strongly opposed to the Iraq War from its onset than any other ethnic group, or even most Americans. The greater opposition to the war was not simply a result of high Democratic identification among Jewish Americans, as Jewish Americans of all political persuasions were more likely to oppose the war than non-Jews who shared the same political leanings.[222][223]

Domestic issues

[edit]A 2013 Pew Research Center survey suggests that American Jews' views on domestic politics are intertwined with the community's self-definition as a persecuted minority who benefited from the liberties and societal shifts in the United States and feel obligated to help other minorities enjoy the same benefits. American Jews across age and gender lines tend to vote for and support politicians and policies which are supported by the Democratic Party. On the other hand, Orthodox American Jews have domestic political views which are more similar to those of their religious Christian neighbors.[224]

American Jews are largely supportive of LGBT rights with 79% responding in a 2011 Pew poll that homosexuality should be "accepted by society", while the overall average in the same 2011 poll among Americans of all demographic groups was that 50%.[225] A split on homosexuality exists by level of observance. Reform rabbis in America perform same-sex marriages as a matter of routine, and there are fifteen LGBT Jewish congregations in North America.[226] Reform, Reconstructionist and, increasingly, Conservative, Jews are far more supportive on issues like gay marriage than Orthodox Jews are.[227] A 2007 survey of Conservative Jewish leaders and activists showed that an overwhelming majority supported gay rabbinical ordination and same-sex marriage.[228] Accordingly, 78% of Jewish voters rejected Prop 8, the bill that banned gay marriage in California. No other ethnic or religious group voted as strongly against it.[229]

A 2014 Pew poll found that American Jews mostly support abortion rights, with 83% answering that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.[230]

In considering the trade-off between the economy and environmental protection, American Jews were significantly more likely than other religious groups (excepting Buddhism) to favor stronger environmental protection.[231]

Jews in America also overwhelmingly oppose current United States marijuana policy.[needs update] In 2009, eighty-six percent of Jewish Americans opposed arresting nonviolent marijuana smokers, compared to 61% for the population at large and 68% of all Democrats. Additionally, 85% of Jews in the United States opposed using federal law enforcement to close patient cooperatives for medical marijuana in states where medical marijuana is legal, compared to 67% of the population at large and 73% of Democrats.[232]

A 2014 Pew Research survey titled "How Americans Feel About Religious Groups", found that Jews were viewed the most favorably of all other groups, with a rating of 63 out of 100.[233] Jews were viewed most positively by fellow Jews, followed by white Evangelicals. Sixty percent of the 3,200 persons surveyed said they had ever met a Jew.[234]

Jewish American culture

[edit]Since the time of the last major wave of Jewish immigration to America (over 2,000,000 Jews from Eastern Europe who arrived between 1890 and 1924), Jewish secular culture in the United States has become integrated in almost every important way with the broader American culture. Many aspects of Jewish American culture have, in turn, become part of the wider culture of the United States.

Language

[edit]| Year | Hebrew | Yiddish |

|---|---|---|

| 1910a | — |

1,051,767

|

| 1920a | — |

1,091,820

|

| 1930a | — |

1,222,658

|

| 1940a | — |

924,440

|

| 1960a | 38,346 |

503,605

|

| 1970a | 36,112 |

438,116

|

| 1980[235] | 315,953

| |

| 1990[236] | 144,292 |

213,064

|

| 2000[237] | 195,374 |

178,945

|

| ^a Foreign-born population only[238] | ||

Most American Jews today are native English speakers. A variety of other languages are still spoken within some American Jewish communities that are representative of the various Jewish ethnic divisions from around the world that have come together to make up all of America's Jewish population.

Many of America's Hasidic Jews, being exclusively of Ashkenazi descent, are raised speaking Yiddish. Yiddish was once spoken as the primary language by most of the several million Ashkenazi Jews who migrated to the United States. It was, in fact, the original language in which The Forward was published. Yiddish has had an influence on American English, and words borrowed from it include chutzpah ('effrontery, gall'), nosh ('snack'), schlep ('drag'), schmuck ('an obnoxious, contemptible person', euphemism for 'penis'), and, depending on idiolect, hundreds of other terms. (See also Yinglish.)

Many Mizrahi Jews, including those from Arab countries such as Syria, Egypt, Iraq, Yemen, Morocco, Libya, etc. speak Arabic. There are communities of Mizrahim in Brooklyn. The town of Deal, New Jersey, is notably mostly Syrian-Jewish, with many of them Orthodox.[239]

The Persian Jewish community in the United States, notably the large community in and around Los Angeles and Beverly Hills, California, primarily speak Persian (see also Judeo-Persian) in the home and synagogue. They also support their own Persian language newspapers. Persian Jews also reside in eastern parts of New York such as Kew Gardens and Great Neck, Long Island.

Many recent Jewish immigrants from the Soviet Union speak primarily Russian at home, and there are several notable communities where public life and business are carried out mainly in Russian, such as in Brighton Beach in New York City and Sunny Isles Beach in Florida. 2010 estimates of the number of Jewish Russian-speaking households in the New York city area are around 92,000, and the number of individuals are somewhere between 223,000 and 350,000.[240] Another high population of Russian Jews can be found in the Richmond District of San Francisco where Russian markets stand alongside the numerous Asian businesses.

American Bukharan Jews speak Bukhori, a dialect of Tajik Persian. They publish their own newspapers such as the Bukharian Times and a large portion live in Queens, New York. Forest Hills in the New York City borough of Queens is home to 108th Street, which is called by some "Bukharian Broadway",[241] a reference to the many stores and restaurants found on and around the street that have Bukharian influences. Many Bukharians are also represented in parts of Arizona, Miami, Florida, and areas of Southern California such as San Diego.

There is a sizeable Mountain Jewish population in Brooklyn, New York, that speaks Judeo-Tat (Juhuri), a dialect of Persian.[242]

Classical Hebrew is the language of most Jewish religious literature, such as the Tanakh (Bible) and Siddur (prayerbook). Modern Hebrew is also the primary official language of the modern State of Israel, which further encourages many to learn it as a second language. Some recent Israeli immigrants to America speak Hebrew as their primary language.

There are a diversity of Hispanic Jews living in America. The oldest community is that of the Sephardi Jews of New Netherland. Their ancestors had fled Spain or Portugal during the Inquisition for the Netherlands, and then came to New Netherland. Though there is dispute over whether they should be considered Hispanic. Some Hispanic Jews, particularly in Miami and Los Angeles, immigrated from Latin America. The largest groups are those that fled Cuba after the communist revolution (known as Jewbans), Argentine Jews, and more recently, Venezuelan Jews. Argentina is the Latin American country with the largest Jewish population. There are a large number of synagogues in the Miami area that give services in Spanish. The last Hispanic Jewish community would be those that recently came from Portugal or Spain, after Spain and Portugal granted citizenship to the descendants of Jews who fled during the Inquisition. All the above listed Hispanic Jewish groups speak either Spanish or Ladino.

Jewish American literature

[edit]Although American Jews have contributed greatly to American arts in general, there still remains a distinctly Jewish American literature. Jewish American literature often explores the experience of being a Jew in America, and the conflicting pulls of secular society and history.

Popular culture

[edit]Yiddish theater was very well attended, and provided a training ground for performers and producers who moved to Hollywood in the 1920s. Many of the early Hollywood moguls and pioneers were Jewish.[243][244] They played roles in the development of radio and television networks, typified by William S. Paley who ran CBS.[245] Stephen J. Whitfield states that "The Sarnoff family was long dominant at NBC."[246]

Many individual Jews have made significant contributions to American popular culture.[247] There have been many Jewish American actors and performers, ranging from early 1900s actors, to classic Hollywood film stars, and culminating in many currently known actors. The field of American comedy includes many Jews. The legacy also includes songwriters and authors, for example the author of the song "Viva Las Vegas" Doc Pomus, or Billy the Kid composer Aaron Copland. Many Jews have been at the forefront of women's issues.

Sports

[edit]

The first generation of Jewish Americans who immigrated during the 1880–1924 peak period were not interested in baseball, the country's national pastime, and in some cases tried to prevent their children from watching or participating in baseball-related activities. Most were focused on making sure they and their children took advantage of education and employment opportunities. Despite the efforts of parents, Jewish children became interested in baseball quickly since it was already embedded in the broader American culture. The second generation of immigrants saw baseball as a means to celebrate American culture without abandoning their broader religious community. After 1924, many Yiddish newspapers began covering baseball, which they had not done previously.[249]

Government and military

[edit]