Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reformation

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Reformation |

|---|

|

| Protestantism |

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

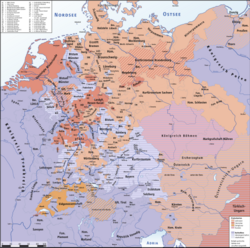

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation,[1] was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church hierarchy. Towards the end of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism. It is considered one of the events that signified the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period in Europe.[2]

The Reformation is usually dated from Martin Luther's publication of the Ninety-five Theses in 1517, which gave birth to Lutheranism. Prior to Martin Luther and other Protestant Reformers, there were earlier reform movements within Western Christianity. The end of the Reformation era is disputed among modern scholars.

In general, the Reformers argued that justification was based on faith in Jesus alone and not both faith and arising charitable acts, as in the Catholic view.[3]: 23 In the Lutheran, Anglican and Reformed view, good works were seen as fruits of living faith and part of the process of sanctification which was distinct from justification.[4][5] Protestantism also introduced new ecclesiology. The general points of theological agreement by the different Protestant groups have been more recently summarized as the three solae, though various Protestant denominations disagree on doctrines such as the nature of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, with Lutherans accepting a corporeal presence and the Reformed accepting a spiritual presence.[6][7]

The spread of Gutenberg's printing press provided the means for the rapid dissemination of religious materials in the vernacular. The initial movement in Saxony, Germany, diversified, and nearby other reformers such as the Swiss Huldrych Zwingli and the French John Calvin developed the Continental Reformed tradition. Within a Reformed framework, Thomas Cranmer and John Knox led the Reformation in England and the Reformation in Scotland, respectively, giving rise to Anglicanism and Presbyterianism.[8][9][10] The period also saw the rise of non-Catholic denominations with quite different theologies and politics to the Magisterial Reformers (Lutherans, Reformed, and Anglicans): so-called Radical Reformers such as the various Anabaptists, who sought to return to the practices of early Christianity.[11][12][13] The Counter-Reformation comprised the Catholic response to the Reformation, with the Council of Trent clarifying ambiguous or disputed Catholic positions and abuses that had been subject to critique by reformers.[14] The consequent European wars of religion saw the deaths of between seven and seventeen million people.

Terminology

[edit]

In the 16th-century context, the term mainly covers four major movements: Lutheranism, Calvinism, the Radical Reformation, and the Catholic Reformation or Counter-Reformation. Since the late 20th century, historians often use the plural of the term to emphasize that the Reformation was not a uniform and coherent historical phenomenon but the result of parallel movements.[15]

Anglican theologian Alister McGrath explains the term "Reformation" as "an interpretative category—a way of mapping out a slice of history in which certain ideas, attitudes, and values were developed, explored, and applied". Historian John Bossy criticized the term Reformation[16] for "wrongly implying that bad religion was giving way to good," but also because it has "little application to actual social behaviour and little or no sensitivity to thought, feeling or culture."[17] A French scholar has noted "no Reformation term is indisputable" and that "Reformation studies has revealed that 'Protestants' and 'Catholics' were not as homogenous as once thought."[18]

Specific terminology includes:

- "Protestant Reformation" excludes the Renaissance and early modern Catholic reform movements.

- "Magisterial Reformation" has a narrower sense, as it refers only to mainstream Protestantism, primarily Lutheranism, Anglicanism and Calvinism, contrasting it with more radical ideas such as the Anabaptists'.[19][11][12]

- "Catholic Reformation" is distinguished by the historian Massimo Firpo from Counter-Reformation. In his view, Catholic Reformation was "centered on the care of souls ..., episcopal residence, the renewal of the clergy, together with the charitable and educational roles of the new religious orders", whereas Counter-Reformation was "founded upon the defence of orthodoxy, the repression of dissent, the reassertion of ecclesiastical authority".[20]

- Some historians have also suggested a persisting "Erasmian Reformation."[note 1]

Several aspects of the Reformation, such as changes in the arts, music, rituals, and communities are frequently presented in specialised studies.[22]

The historian Peter Marshall emphasizes that the "call for 'reform' within Christianity is about as old as the religion itself, and in every age there have been urgent attempts to bring it about". Charlemagne employed a "rhetoric of reform".[note 2] Medieval examples include the Cluniac Reform in the 10th–11th centuries, and the 11th-century Gregorian Reform,[24] both striving against lay influence over church affairs.[25][26] When demanding a church reform, medieval authors mainly adopted a conservative and utopian approach, expressing their admiration for a previous "golden age" or "apostolic age" when the Church had allegedly been perfect and free of abuses.[27]

When considered as a historical time period, both the starting and ending date of the Reformation have always been debated.[28] The most commonly used starting date is 31 October 1517—the day when the German theologian Martin Luther (d. 1546) allegedly nailed up a copy of his disputation paper on indulgences and papal power known as the Ninety-five Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg in Electoral Saxony.[note 3][31] Calvinist historians often propose that the Reformation started when the Swiss priest Huldrych Zwingli (d. 1531) first preached against abuses in the Church in 1516.[32] The end date of the Reformation is even more disputed: considered as political/martial strife, 25 September 1555 (when the Peace of Augsburg was accepted), 23 May 1618 and 24 October 1648 (when the Thirty Years' War began and ended, respectively) are the most commonly mentioned terminuses. The Reformation has always been presented as one of the most crucial episodes of the early modern period, or even regarded as the event separating the modern era from the Middle Ages.[33]

The term Protestant, though initially purely political in nature, later acquired a broader sense, referring to a member of any Western church that subscribed to the main Reformation (or anti-Catholic) principles.[34] Six princes of the Holy Roman Empire and rulers of fourteen Imperial Free Cities, who issued a protest (or dissent) against the edict of the Diet of Speyer (1529), were the first individuals to be called Protestants.[34] The edict reversed concessions made to the Lutherans with the approval of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V three years earlier.

Background

[edit]Calamities

[edit]

Europe experienced a period of dreadful calamities from the early 14th century. These culminated in a devastating pandemic known as the Black Death, which killed about one-third of Europe's population.[35] Around 1500, the population of Europe was about 60–85 million people—no more than 75 percent of the mid-14th-century demographic maximum.[36] Due to a shortage of workforce, the landlords began to restrict the rights of their tenants which led to rural revolts that often ended with a compromise.[37]

The constant fear of unexpected death was mirrored by popular artistic motifs, such as the allegory of danse macabre ('dance of death'). The fear also contributed to the growing popularity of Masses for the dead.[38] Already detectable among early Christians, these ceremonies indicated a widespread belief in purgatory—a transitory state for souls that needed purification before entering heaven.[39] Fear of malevolent magical practice was also growing, and witch hunts intensified.[40]

At the end of the 15th century, the sexually transmitted infection known as syphilis spread throughout Europe for the first time. Syphilis destroyed its victims' looks with ulcers and scabs before killing them. Along with the French invasion of Italy, syphilis contributed to the success of the charismatic preacher Girolamo Savonarola (d. 1498) who called for a moral renewal in Florence. He was arrested and executed for heresy, but his meditations remained a popular reading.[41]

Late Medieval Christianity

[edit]

Lay community

[edit]Historian John Bossy (as summarized by Eamon Duffy[43]) emphasized that "medieval Christianity had been fundamentally concerned with the creation and maintenance of peace in a violent world. 'Christianity' in medieval Europe denoted neither an ideology nor an institution, but a community of believers whose religious ideal—constantly aspired to if seldom attained—was peace and mutual love."[note 4][45]

The Catholic Church taught that entry into heaven required dying in a state of grace.[39] Based on Christ's parable on the Last Judgement, the Church emphasized the performance of charitable acts by the baptized faithful, such as feeding the hungry and visiting the sick, as an important co-condition of salvation.[46]

Villagers and urban laypeople were frequently members of confraternities (such as the Archconfraternity of the Gonfalone),[47][48][note 5] mutual-support guilds associated with a saint, or religious fraternities (such as the Third Order of Saint Francis). The faithful made pilgrimages to saints' shrines,[51] but the proliferation in the saints' number undermined their reputation.[note 6][53] There was a strong non-theological Biblical awareness,[note 7] especially of the Gospels and Psalms.

New religious movements promoted the deeper involvement of laity in religious practices. The communal fraternities of the Brethren of the Common Life did not encourage lay brothers to become priests[57] and often placed their houses under the protection of urban authorities.[58] They were closely associated with the devotio moderna, a new method of Catholic spirituality with a special emphasis on the education of laypeople.[59] A leader of the movement the Dutch Wessel Gansfort (d. 1489) attacked abuses of indulgences.[60]

Church buildings were richly decorated with paintings, sculptures, and stained glass windows. While Romanesque and Gothic art made a clear distinction between the supernatural and the human, Renaissance artists depicted God and the saints in a more human way.[61] Historian Caroline Walker Bynum has written of 'a sort of religious materialism' in the period: 'a frenzied conviction that the divine tended to erupt into matter'.[62]

Sources of authority

[edit]The sources of religious authority included the Bible and its authoritative commentaries, apostolic tradition, decisions by ecumenical councils, scholastic theology, and papal authority. Catholics regarded the Vulgate as the Bible's authentic Latin translation. Commentators applied several methods of interpretations to resolve contradictions within the Bible.[note 8] Apostolic tradition verified religious practices with unclear Biblical foundations or which required deduction, such as infant baptism.[64]: 22, 23, 28 The ecumenical councils' decisions were binding to all Catholics. The crucial elements of mainstream Christianity had been first summarised in the Nicene Creed in 325. Its western text contained a unilateral addition which contributed to the schism between Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[65] The Creed contained the dogma of Trinity about one God uniting three equal persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.[66][67] Church authorities acknowledged that an individual might exceptionally receive direct revelations from God but maintained that a genuine revelation could not challenge traditional religious principles.[note 9][69] Preaching was an important part of bishops' and priests' responsibilities.[note 10]

Clergy

[edit]Western Christianity displayed a remarkable unity. This was the outcome of the Gregorian Reform that established papal supremacy over the Catholic Church, and achieved the legal separation of the Catholic clergy from laity.[70][note 11] Clerical celibacy was reinforced through the prohibition of clerical marriage; ecclesiastical courts were granted exclusive jurisdiction over clerics, and also over matrimonial causes.[73] Priests were ordained by bishops in accordance with the principle of apostolic succession—a claim to the uninterrupted transmission of their consecrating power from Christ's Apostles through generations of bishops.[74] Bishops, abbots, abbesses, and other prelates might possess remarkable wealth.[75] Some of the ecclesiastic leaders also functioned as local secular princes, such as the prince-bishops in Kingdom of Germany and the English County Palatine of Durham, and the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Knights in their Baltic Ordensstaat. Other prelates might be regents or the power behind the throne.[note 12][76] Believers were expected to pay the tithe (one tenth of their income) to the Church.[77] Pluralism—the practice of holding multiple Church offices (or benefices)—was not unusual. This led to non-residence, and the absent priests' deputies were often poorly educated and underpaid.[78]

The clergy consisted of two major groups, the regular clergy and the secular clergy. Regular clerics lived under a monastic rule within the framework of a religious order;[79] secular clerics were responsible for pastoral care. The Church was a hierarchical organisation. The pope was elected by high-ranking clergymen, the cardinals, and assisted by the professional staff of the Roman Curia. Secular clerics were organised into territorial units known as dioceses, each ruled by a bishop or archbishop.[note 13] Each diocese was divided into parishes headed by parish priests who administered most sacraments to the faithful.[80] These were sacred rites thought to transfer divine grace to humankind. The Council of Florence declared baptism, confirmation, marriage, extreme unction, penance, the Eucharist, and priestly ordination as the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church.[81] Women were not ordained priests but could live as nuns in convents after taking the three monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.[82]

Papacy

[edit]

The authority of the papacy was based on a well-organised system of communication and bureaucracy.[83] The popes claimed the power of binding and loosing that Christ had reportedly granted to Peter the Apostle (d. c. 66), and offered indulgence—the reduction of the penalty in both this world (penance) and in Purgatory to contrite and pardoned sinners who e.g. gave alms or went on pilgrimages.[84] The popes also granted dispensations to institutions or individuals, exempting them from certain provisions of canon law (or ecclesiastic law).[note 14][78]

From 1309 to 1417, the papacy was in turmoil: various election controversies resulted in the Western Schism (1378-1417) leading to, at the end, three rival claimant Popes. At the Council of Constance, one of the three popes resigned, his two rivals were deposed, and the newly elected Martin V (r. 1417–1431) was acknowledged as the legitimate pope throughout Catholic Europe.[85] The relative authority of popes and ecumenical councils was in contest.

The Renaissance popes were also secular rulers: as princes of the Papal States in Italy, the popes were deeply involved in the power struggles of the peninsula, and the Italian noble houses vied for election. These popes frequently caused scandal: Pope Alexander VI (r. 1492–1503) appointed his relatives, among them his own illegitimate sons to high offices; Pope Julius II (r. 1503–1513) took up arms to recover papal territories lost during his predecessors' reign,[86] prompting the underground satire Julius Excluded from Heaven.

In the early Age of Exploration, a succession of popes (Nicholas V, Sixtus IV, Alexander VI) successfully arbitrated territorial disputes between Spain and Portugal outside Europe, notably with the papal bull Inter caetera (1493) drawing a line through South America to separate their trade and colonial regions.[87][88] The Spanish and Portuguese conquests and developing trade networks contributed to the global expansion of Catholicism.[note 15][89]

The popes were generous patrons of art and architecture. Julius II ordered the demolition of the ruined 4th-century St. Peter's Basilica in preparation for the building of a new Renaissance basilica, creating a financial problem.[90]

Partial and failed institutional reforms

[edit]The necessity of a church reform in capite et membris ('in head and limbs') was frequently discussed at the ecumenical councils from the late 13th century. However, many high stakeholders—popes, prelates, abbots and kings—preferred the status quo because they did not want to lose privileges or revenues.[91] The system of papal dispensations proved a continual obstacle to the implementation of each revived reform attempt, as the Holy See had regularly granted privileges or immunities.[78]

Within regular clergy, the so-called "congregations of strict observance" spread. These were monastic communities that returned to the strict interpretation of their order's rule.[note 16] Reformist bishops tried to discipline their clergy through regular canonical visitations but their attempts mainly failed due to the resistance of autonomous institutions such as cathedral chapters. Neither could they exercise authority over non-resident clerics who had received their benefice from the papacy.[93] On the eve of the Reformation, the Fifth Council of the Lateran was the last occasion when efforts to introduce a far-reaching reform from above could have achieved but it was dissolved in 1517 without making decisions on the issues that would soon come to the fore.[94]

Humanism

[edit]

A new intellectual movement known as Humanism emerged in the Late Middle Ages. The Humanists' slogan ad fontes! ('back to the sources!') demonstrated their enthusiasm for Classical texts and textual criticism.[95] The rise of the Ottoman Empire led to the mass immigration of Byzantine scholars to Western Europe, and many of them brought manuscripts previously unknown to western scholarship. This led to the rediscovery of the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato (347/348 BC). Plato's ideas about an ultimate reality lying beyond visible reality posed a serious challenge to scholastic theologians' rigorous definitions. Textual criticism called into question the reliability of some of the fundamental texts of papal privilege: humanist scholars, like Nicholas of Cusa (d. 1464) proved that one of the basic documents of papal authority, the allegedly 4th-century Donation of Constantine was a medieval forgery.[96]

As the manufacturing of paper from rags and the printing machine with movable type were spreading in Europe, books could be bought at a reasonable price from the 15th century.[note 17] Demand for religious literature was especially high.[98] The German inventor Johannes Gutenberg (d. 1468) first published a two-volume printed version of the Vulgata in the early 1450s.[99] High and Low German, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, Czech and Catalan translations of the Bible were published between 1466 and 1492; in France, the Bible's abridged French versions gained popularity.[100] Laypeople who read the Bible could challenge their priests' sermons, as it happened already in 1515.[101]

Completed by Jerome (d. 420), the Vulgate contained the Septuagint version of the Old Testament.[102] The systematic study of Biblical manuscripts revealed that Jerome had sometimes misinterpreted his sources of translation.[note 18][103] A series of Latin-Greek editions of the New Testament was completed by the Dutch humanist Erasmus (d. 1536). These new Latin translations challenged some scriptural proof texts for some Catholic dogmas.[note 19][106]

Dissidents

[edit]

After Arianism—a Christological doctrine condemned as heresy at ecumenical councils—disappeared in the late 7th century, no major disputes menaced the theological unity of the Western Church. Religious enthusiasts could organise their followers into nonconformist groups but they disbanded after their founder died.[note 20] The Waldensians were a notable exception. Due to their efficient organisation, they survived not only the death of their founder Peter Waldo (d. c. 1205), but also a series of anti-heretic crusades. They rejected the clerics' monopoly of public ministry, and allowed all trained members of their community, men and women alike, to preach.[108]

The Western Schism reinforced a general desire for church reform. The Oxford theologian John Wycliffe (d. 1384) was one of the most radical critics.[109] He attacked pilgrimages, the veneration of saints, and the doctrine of transubstantiation.[110] He regarded the Church as an exclusive community of those chosen by God to salvation,[111] and argued that the state could seize the corrupt clerics' endowments.[112] Known as Lollards, Wycliffe's followers rejected images, clerical celibacy and the purchase of indulgences by crusading lords. The Parliament of England passed a law against heretics, but Lollard communities survived the purges.[111][113]

Wycliffe's theology had a marked impact on the Prague academic Jan Hus (d. 1415). He delivered popular sermons against the clerics' wealth and temporal powers, for which he was summoned to the Council of Constance. Although the German king Sigismund of Luxemburg (r. 1410–1437) had granted him safe conduct, Hus was sentenced to death for heresy and burned at the stake on 6 July 1415. His execution led to a nationwide religious movement in Bohemia, and the papacy called for a series of crusades against Hus's followers. The moderate Hussites, mainly Czech aristocrats and academics, were known as Utraquists for they taught that the Eucharist was to be administered sub utraque specie ('in both kinds') to the laity. The most radical Hussites, called Taborites after their new town of Tábor, held their property in common. Their millenarianism shocked the Utraquists who destroyed them in the Battle of Lipany in 1434.[114][115] By this time, the remaining Catholic communities in Bohemia were almost exclusively German-speaking. The lack of a Hussite church hierarchy enabled the Czech aristocrats and urban magistrates to assume control of the Hussite clergy from the 1470s. The radical Hussites set up their own Church known as the Union of Bohemian Brethren. They rejected the separation of clergy and laity, and condemned all forms of violence and oath taking.[116]

Marshall writes that the Lollards, Hussites and conciliarist theologians "collectively give the lie to any suggestion that torpor and complacency were the hallmarks of religious life in the century before Martin Luther."[109] Historians customarily refer to Wycliffe and Hus as "Forerunners of the Reformation". The two reformers' emphasis on the Bible is often regarded as an early example of one of the basic principles of the Reformation—the idea sola scriptura ('by the Scriptures alone'), although prominent scholastic theologians were also convinced that Scripture, interpreted reasonably and in accord with the Church and the Church Fathers,[117] contained all knowledge necessary for salvation.[note 21][120]

Beginnings

[edit]The Reformation in Germanic countries was instigated by Martin Luther, however historians note that many of his ideas were pre-dated by Wycliff, Huss, Erasmus, Zwingli and others, both heretic and orthodox. Historian Peter Marshall has noted "In recent decades, scholars have become increasingly acclimatized to the idea that the Reformation was in important respects a continuation and intensification of trends within later medieval Catholicism, rather than simply a wholesale rejection of it."[62]

Luther and the Ninety-five Theses

[edit]

Pope Leo X (r. 1513–1521) decided to complete the construction of the new St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, which had already started in 1506 under Pope Julius II..[121] As the sale of certificates of indulgences had been a well-established method of papal fund raising, he announced a new plenary indulgence in the papal bull Sacrosanctis in 1515, intending to finance the construction. On the advice of the banker Jakob Fugger (d. 1525), he appointed the pluralist prelate Albert of Brandenburg (d. 1545) to supervise the sale campaign in Germany.[note 22] The Dominican friar Johann Tetzel (d. 1519), the commissioner of indulgences in the dioceses of Magdeburg and Halberstadt since January 1517, applied unusually aggressive marketing methods. A slogan attributed to him famously claimed that "As soon as the coin into the box rings, a soul from purgatory to heaven springs".[123][124] Frederick the Wise, Prince-elector of Saxony (r. 1486–1525) forbade the campaign because the Sacrosanctis suspended the sale of previous indulgences, depriving him of revenues that he had spent on his collection of relics.[note 23][60]

The campaign's vulgarity shocked many serious-minded believers,[60] among them Martin Luther, a theology professor at the University of Wittenberg in Saxony.[124][126] Born into a middle-class family, Luther entered an Augustinian monastery after a heavy thunderstorm dreadfully reminded him the risk of sudden death and eternal damnation, but his anxiety about his sinfulness did not abate.[127] His studies on the works of the Late Roman theologian Augustine of Hippo (d. 430) convinced him that those whom God chose as his elect received a gift of faith independently of their acts.[128] He first denounced the idea of justification through human efforts in his Disputatio contra scholasticam theologiam ('Disputation against Scholastic Theology') in September 1517.[129]

On 31 October 1517, Luther addressed a letter to Albert of Brandenburg, stating that the clerics preaching the St. Peter's indulgences were deceiving the faithful, and attached his Ninety-five Theses to it. He questioned the efficacy of indulgences for the dead, although also stated "If ... indulgences were preached according to the spirit and intention of the pope, all ... doubts would be readily resolved".[130] Archbishop Albert ordered the theologians at the University of Mainz to examine the document. Tetzel, and the theologians Konrad Wimpina (d. 1531) and Johann Eck (d. 1543) were the first to associate some of Luther's propositions with Hussitism. The case was soon forwarded to the Roman Curia for judgement.[131] Pope Leo remained uninterested, and mentioned the case as "a quarrel among friars".[124][132]

New theology

[edit]Christians should be exhorted to seek earnestly to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, hells. And let them thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.

As the historian Lyndal Roper notes, the "Reformation proceeded by a set of debates and arguments".[134] Luther presented his views in public at the observant Augustinians' assembly in Heidelberg on 26 April 1518.[135] Here he explained his "theology of the Cross" about a loving God who had become frail to save fallen humanity, contrasting it with what he saw as the scholastic "theology of glory" that in his view celebrated erudition and human acts.[132] It is uncertain when Luther's concept of justification by faith alone—a central element of his theology—crystallised. He would later attribute it to his "tower experience"[note 24] (1519),[137] when he comprehended that God could freely declare even sinners righteous while he was thinking about the words of Paul the Apostle (d. 64 or 65)—"the just shall live by faith".[138][139]

Urged by Luther's opponents, Pope Leo appointed the jurist Girolamo Ghinucci (d. 1541) and the theologian Sylvester Mazzolini (d. 1527) to inspect Luther's teaching.[140] Mazzolini argued that Luther had questioned papal authority by attacking the indulgences, while Luther concluded that only a fundamental reform could put an end to the abuse of indulgences.[141] Pope Leo did not excommunicate Luther because Leo did not want to alienate Luther's patron Frederick the Wise.[note 25] Instead, he appointed Cardinal Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534) to convince Luther to withdraw some of his theses. Cajetan met with Luther at Augsburg in October 1518.[29] The historian Berndt Hamm says that the meeting was the "historical point at which the opposition between the Reformation and Catholicism first emerged",[note 26] as Cajetan thought that believers accepting Luther's views of justification would no more obey clerical guidance.[142][143]

Luther first expressed his sympathy for Jan Hus at a disputation in Leipzig in June 1519. His case was reopened at the Roman Curia. Cajetan, Eck and other papal officials drafted the papal bull Exsurge Domine ('Arise, O Lord') which was published on 15 June 1520. It condemned Luther's forty-one theses, and offered a sixty-day-long grace period to him to recant.[144] Luther's theology quickly developed. In a Latin treatise On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church (October 1520), he stated that only baptism and the Eucharist could be regarded as sacraments, and priests were not members of a privileged class but servants of the community (hence they became called ministers from the Latin word for servant). His German manifesto To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (August 1520) associated the papacy with the Antichrist, and described the Holy See as "the worst whorehouse of all whorehouses" in reference to the funds flowing to the Roman Curia.[145][146] It also challenged the Biblical justification of clerical celibacy.[147] Luther's study On the Freedom of a Christian (November 1520) consolidated his thoughts about the believers' inner freedom with their obligation to care for their neighbours although he rejected the traditional teaching about good works.[148] The study is a characteristic example of Luther's enthusiasm for paradoxes.[note 27][149]

The papal nuncio Girolamo Aleandro (d. 1542) ordered the burning of Luther's books.[150] In response, Luther and his followers burned the papal bull along with a copy of the Corpus Juris Canonici—the fundamental document of medieval ecclesiastic law—at Wittenberg. The papal bull excommunicating Luther was published on 3 January 1521.[151][152] The newly elected Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (r. 1519–1556) wanted to outlaw Luther at the Diet of Worms, but could not make the decision alone.[153] The Holy Roman Empire was a confederation of autonomous states, and authority rested with the Imperial Diets where the Imperial Estates assembled.[154] Frederick the Wise vetoed the imperial ban against Luther, and Luther was summoned to Worms to defend his case at the Diet in April 1521. Here he refused to recant stating that only arguments from the Bible could convince him that his works contained errors.[153]

After Luther and his supporters left the Diet, those who remained sanctioned the imperial ban, threatening Luther's supporters with imprisonment and confiscation of their property.[155] To save Luther's life but also to hide his involvement, Frederick arranged Luther's abduction on 4 May.[153] During his ten-month-long[155] staged captivity at Frederick's castle of Wartburg, Luther translated the New Testament to High German. The historian Diarmaid MacCulloch describes the translation as an "extraordinary achievement that has shaped the German language ever since", adding that "Luther's gift was for seizing the emotion with sudden, urgent phrases".[156] The translation would be published at the 1522 Leipzig Book Fair along with Luther's treatise On Monastic Vows that laid the theological foundations of the dissolution of monasteries.[157] Luther also composed religious hymns in Wartburg. They would be first published in collections in 1524.[158] During Luther's absence, his co-workers, primarily Philip Melanchthon (d. 1560) and Andreas Karlstadt (d. 1541) assumed the leadership of Reformation in Wittenberg. Melanchthon consolidated Luther's thoughts into a coherent theological work titled Loci communes ('Common Places').[159]

Spread

[edit]

Roper argues that "the most important reason why Luther did not meet with Hus's fate was technology: the new medium of print". Luther was publishing his views in short but pungent treatises that gained unexpected popularity: he was responsible for about one-fifth of all works printed in Germany in the first third of the 16th century.[note 28][161] German printing presses were scattered in many urban centers which prevented their control by central authorities.[162] Statistical analysis indicates a significant correlation between the presence of a printing press in a German city and the adoption of Reformation.[note 29][165]

Reformation spread through the activities of enthusiastic preachers such as Johannes Oecolampadius (d. 1531) and Konrad Kürsner (d. 1556) in Basel, Sebastian Hofmeister (d. 1533) in Schaffhausen, and Matthäus Zell (d. 1548) and Martin Bucer (d. 1551) in Strasbourg.[166] They were called "Evangelicals" due to their insistence on teaching in accordance with the Gospels (or Evangelion).[167] Luther and many of his followers worked with the artist Lucas Cranach the Elder (d. 1553) who had a keen sense of visualising their message. He produced Luther's idealised portrait setting a template for further popular images printed on the covers of books.[168] Cranach's woodcuts together with itinerant preachers' explanations helped the mainly illiterate people to understand Luther's teaching.[169] The illustrated pamphlets were carried from place to place typically by peddlers and merchants.[170] Laypeople started to discuss various aspects of religion in both private and public all over Germany.[171]

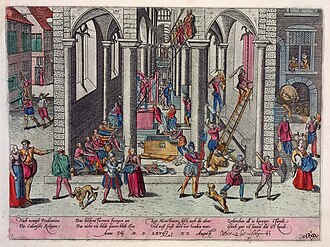

The self-governing free imperial cities were the first centers of the Reformation.[172] The Evangelical preachers emphasized that many well-established church practices had no precedent in the Bible, which they considered necessary. They offered the Eucharist to the laity in both kinds,[173] and denied the clerics' monopolies, which resonated with popular anti-clericalism.[174] It was not unusual that their supporters attacked clerics and church buildings.[175] Violent iconoclasm was common.[note 30]In some cities such as Strasbourg and Ulm, the urban magistrates supported the Reformation; in the cities of the Hanseatic League the affluent middle classes enforced changes in church life.[177] Cities located closer to the most important ideological centers of the Reformation—Wittenberg and Basel—adopted its ideas more likely than other towns. This indicates the significance either of student networks,[178] or of neighbours who had rejected Catholicism.[179]

The sociologist Steven Pfaff underlines that "ecclesiastical and liturgical reform was not simply a religious question ... since the sort of reforms demanded by Evangelicals could not be accommodated within existing institutions, prevailing customs, or established law". After their triumph, the reformers expelled their leading opponents, dissolved the monasteries and convents, secured the urban magistrates' control of the appointment of priests, and established new civic institutions.[180] Evangelical town councils usually prohibited begging but established a common chest for poverty relief by expropriating the property of dissolved ecclesiastic institutions. The funds were used for the daily support of orphans, old people and the sick, but also for low-interest loans to the impoverished to start a business. Luther was convinced that only educated people could effectively serve both God and the community. Under his auspices, public schools and libraries were opened in many towns offering education to more children than the traditional monastic and cathedral schools.[181]

Resistance and oppression

[edit]

Resistance to Evangelical preaching was significant in Flanders, the Rhineland, Bavaria and Austria.[183] Here the veneration of local saints was strong, and statistical analysis indicates that cities where indigenous saints' shrines served as centers of vivid communal cults less likely adopted Reformation.[note 31][185] Likewise, cities with an episcopal see or monasteries more likely resisted Evangelical proselytism.[186][187]

Luther's ideas were rejected by most representatives of the previous generation of Humanists. Erasmus stated that Luther's "unrestrained enthusiasm carries him beyond what is right". Jacob van Hoogstraaten (d. 1527) compared Luther's theology of salvation "as if Christ takes to himself the most foul bride and is unconcerned about her cleanliness".[188] Luther's works were burned in most European countries.[189] Emperor Charles initiated the execution of the first Evangelical martyrs, the Augustinian monks Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos. They were burned in Brussels on 1 July 1523.[190] Charles was determined to protect the Catholic Church, but the Ottoman Turks' expansion towards Central Europe often thwarted him.[191][192] The Spanish Inquisition prevented the spread of Evangelical literature in that country, and suppressed the spiritual movement of the Alumbrados ('Illuminists') who put a special emphasis on personal faith. Some Italian men of letters, such as the Venetian nobleman Gasparo Contarini (d. 1542) and the Augustinian canon Peter Martyr Vermigli (d. 1562) expressed ideas resembling Luther's theology of salvation but did not quickly break with Catholicism.[note 32] They were part of a group known as Spirituali.[195][196]

The English king Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547) commissioned a team of theologians to defend the Catholic dogmas against Luther's attacks. Their treatise titled The Assertion of the Seven Sacraments was published under Henry's name, and the grateful Pope awarded him with the title Defender of the Faith.[189][197] In Scotland, the first Evangelical preacher Patrick Hamilton (d. 1528) was burned for heresy.[198] In France, the theologians of the Sorbonne stated that Luther "vomited up a doctrine of pestilence". Guillaume Briçonnet (d. 1534), Bishop of Meaux, also condemned Luther but employed reform-minded clerics like Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (d. c. 1536) and William Farel (d. 1565) to renew religious life in his diocese. They enjoyed the protection of Marguerite of Angoulême (d. 1549), the well-educated sister of the French king Francis I (r. 1515–1547). The Parlement of Paris only took actions against them after Francis was captured in the Battle of Pavia in 1525, forcing many of them into exile.[199]

Correspondence between Luke of Prague (d. 1528), leader of the Bohemian Brethren, and Luther made it clear that their theologies were incompatible even if their views about justification were similar. In Bohemia, Hungary, and Poland, Luther's theology spread in the local German communities. King Louis of Bohemia and Hungary (r. 1516–1526) ordered the persecution of Evangelical preachers although his wife Mary of Austria (d. 1558) favoured the reformers. Sigismund I the Old, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (r. 1506–1548) banned the import of Evangelical literature.[200] Christian II, who ruled the Kalmar Union of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway (r. 1513–1523), was sympathetic towards the Reformation but his despotic methods led to revolts. He was replaced by his uncle Frederick I in Denmark and Norway (r. 1523–1533), and by a local aristocrat Gustav I Vasa in Sweden (r. 1523–1560).[201]

Alternatives

[edit]Saxon radicals and rebellious knights

[edit]Andreas Karlstadt accelerated the implementation of Reformation in Wittenberg. On Christmas Day 1521, he administered the Eucharist in common garment; the next day he announced his engagement to a fifteen-year-old noble girl Anna von Mochau.[202] He proclaimed that images were examples of "devilish deceit" which led to the mass destruction of religious art. Enthusiasts began swarming to Wittenberg. The Zwickau prophets, who had been incited by the radical preacher Thomas Müntzer (d. 1525), claimed that they had received revelations from God.[203][204] They rejected transubstantiation and attacked infant baptism. Luther defended art as a proof of the beauty of the Creation, maintained that Christ's Body and Blood were physically present in the Eucharist,[note 33] and regarded infant baptism as a sign of membership in the Christian community.[note 34] To put an end to the anarchy, Frederick the Wise released Luther in March 1522. Luther achieved the Zwickau prophets' removal from Wittenberg, calling them fanatics.[207] Karlstadt voluntarily left Wittenberg for Orlamünde where the local congregation elected him its minister. Luther visited most parishes in the region to prevent radical reforms, but he was often received by verbal or physical abuses. When he wanted to dismiss Karlstadt, the parishioners referred to his own words about the congregations' right to freely elect their ministers, and Karlstadt called him a "perverter of the Scriptures". Karlstadt was expelled from Electoral Saxony without a trial on Luther's initiative.[208]

Luther condemned violence but some of his followers took up arms. Franz von Sickingen (d. 1523), an imperial knight from the Rhineland, formed an alliance with his peers against Richard von Greiffenklau, Archbishop-elector of Trier (r. 1511–1531), allegedly to lead the Archbishop's subjects "to evangelical, light laws and Christian freedom".[209] Sickingen had demanded the restitution of monastic property to the grantors' descendants, stating that the secularisation of church property would also improve the poor peasants' situation.[210] Sickingen and his associates attacked the archbishopric but failed at the siege of Trier. Sickingen was mortally wounded while defending his Nanstein Castle against the Archbishop's troops.[209] Luther denounced Sickingen's violent acts.[211] According to his "theory of two kingdoms", true Christians had to submit themselves to princely authority.[212]

Zwingli

[edit]

The Swiss Humanist priest Huldrych Zwingli would claim that he "began to preach the Gospel of Christ in 1516 long before anyone in our region had ever heard of Luther". He came to prominence when attended a meal of sausages in Zürich during Lent 1522, breaching the rules of fasting.[213] He held disputations with the urban magistrates' authorization to discuss changes in church life, and always introduced them with the magistrates' support. In 1524, all images were removed from the churches, and fasting and clerical celibacy were abolished. Two years later, a German communion service replaced the Latin liturgy of the Mass, and the Eucharist (or Lord's Supper) was administered on a plain wooden table instead of an embellished altar.[213][214] Two new institutions were organised in Zürich: the Prophezei (a public school for Biblical studies), and the Marriage and Morals Court (a legal court and moral police consisting of two laymen and two clerics). Both would be copied in other towns.[215] Zwingli's interpretation of the Eucharist differed from both Catholic theology and Luther's teaching. He denied Christ's presence in the sacramental bread and wine, and regarded the Eucharist as a commemorative ceremony in honor of the crucified Jesus.[216] The disagreement caused a bitter pamphlet war between Luther and Zwingli.[217] They both rejected intermediary Eucharistic formulas coined by Bucer.[218]

Swiss Brethren

[edit]Zwingli's cautious "Magisterial Reformation" outraged the more radical reformers, among them Conrad Grebel (d. 1526), a Zürich patrician's son who had fallen out with his family for marrying a low born girl. The radicals summarized their theology in a letter to Müntzer in 1524. They identified the Church as an exclusive community of the righteous, and demanded its liberation from the state. They deplored all religious practices that had no Biblical foundations, and endorsed believers' (or adult) baptism.

In January 1525, a former Catholic priest George Blaurock (d. 1529) asked Grebel to rebaptize him, and after his request was granted they rebaptized fifteen other people.[219] For this practice, they were called Anabaptists ('rebaptizers').[220] As a featuring element of Donatism and other heretic movements, rebaptism had been a capital offence since the Late Roman period. After the magistrates had some radicals imprisoned, Blaurock called Zwingli the Antichrist.[221] The town council enacted a law that threatened rebaptizers with capital punishment, and the Anabaptist Felix Manz (d. 1527) was condemned to death and drowned in the Limmat River.[222] He was the first victim of religious persecution by reformist authorities. The purge convinced many Anabaptists that they were the true heirs to early Christians who had suffered martyrdom for their faith. The most radicals took inspiration from the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelation for apocalyptic prophesies. Some of them burnt the Bible reciting St Paul's words, "the letter kills".[223] In St. Gallen, Anabaptist women cut their hair short to avoid arousing sexual passion, while a housemaid Frena Bumenin proclaimed herself the New Messiah before announcing that she would give birth to the Antichrist.[224]

According to Dr Kenneth R. Davis, "the Anabaptists can best be understood as, apart from their own creativity, a radicalization and Protestantization not of the Magisterial Reformation but of the lay-oriented, ascetic reformation of which Erasmus is the principle mediator."[225]: 292

Peasants' War

[edit]

MacCulloch says that the Reformation "injected an extra element of instability" into the relationship between the peasants and their lords, as it raised "new excitement and bitterness against established authority".[226] Public demonstrations in the Black Forest area indicated a general discontent among the southern German peasantry in May 1524. The Anabaptist preacher Balthasar Hubmaier (d. 1528) was one of the peasant leaders, but most participants never went beyond traditional anti-clericalism. In early 1525, the movement spread towards Upper Swabia. The radical preacher Cristopher Schappler and the pamphleteer Sebastian Lotzer summarized the Swabian peasants' demand in a manifesto known as Twelve Articles. The peasants wanted to control their ministers' election and to supervise the use of church revenues, but also demanded the abolition of the tithe on meat. They reserved the right to present further demands against non-Biblical seigneurial practices but promised to abandon any of their demands that contradicted the Bible, and appointed fourteen "arbitrators" to clarify divine law on the relationship between peasants and landlords. The arbitrators approached Luther, Zwingli, Melanchthon and other leaders of the Reformation for advice but none of them answered.[227] Luther wrote a treatise, equally blaming the landlords for the oppression of the peasantry and the rebels for their arbitrary acts.[228]

Georg Truchsess von Waldburg (d. 1531), commander of the army of the aristocratic Swabian League, achieved the dissolution of the peasant armies either by force or through negotiations. By this time the peasant movements reached Franconia and Thüringia. The Franconian peasants formed alliances with artisans and petty nobles such as Florian Geyer (d. 1525) against the patricians and the Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg but Truchsess forced them into submission.[229] In Thüringia, Müntzer convinced 300 radicals that they were invincible but they were annihilated at Frankenhausen by Philip the Magnanimous, Landgrave of Hesse (r. 1509–1567) and George, Duke of Saxony (r. 1500–1539). Müntzer who had hidden in an attic before the battle was discovered and executed.[230][231] News of atrocities by peasant bands and meetings with disrespectful peasants during a preaching tour outraged Luther while he was writing his treatise Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants. In it, he urged the German princes to "smite, slay, and slab" the rebels.[232] Moderate observers felt aggrieved at his cruel words. They regarded as an especially tasteless act that Luther married Katharina von Bora (d. 1552), a former nun while the punitive actions against the peasantry were still in process.[233] Further peasant movements began in other regions in Central Europe but they were pacified through concessions or suppressed by force before the end of 1525.[234]

Consolidation

[edit]Princely Reformation in Germany

[edit]

The Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights Albert of Brandenburg-Ansbach (r. 1510–1525) was the first prince to formally abandon Catholicism. The Teutonic Order held Royal Prussia in fief of Poland. After defeats in a war against Poland and Lithuania demoralised the Knights, Albert transformed the region into the hereditary Duchy of Prussia in April 1525. As the secularisation of Prussia represented an open rebellion against Catholicism, it was followed by the establishment of the first Evangelical state church.[235] In August, Albert's brothers, Casimir (r. 1515–1527) and George (r. 1536–1543) instructed the priests in Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Brandenburg-Ansbach to pray the doctrine of justification by faith alone.[236] The Reformation was officially introduced in Electoral Saxony under John the Constant (r. 1525–1532) on Christmas Day 1525.[237] Electoral Saxony's conversion facilitated the adoption of the Reformation in smaller German states, such as Mansfeld and Hessen.[238][239] Philip of Hessen founded the first Evangelical university at his capital Marburg in 1527.[240]

At the Diet of Speyer in 1526, the German princes agreed that they would "live, govern, and act in such a way as everyone trusted to justify before God and the Imperial Majesty".[241] In practice, they sanctioned the principle cuius regio, eius religio ('whose realm, their religion'), acknowledging the princes' right to determine their subjects' religious affiliation.[242] Fully occupied with the War of the League of Cognac against France and its Italian allies, Emperor Charles had appointed his brother Ferdinand I, Archduke of Austria (r. 1521–1564) to represent him in Germany. They both opposed the compromise, but Ferdinand was brought into succession struggles in Bohemia and Hungary after their brother-in-law King Louis died in the Battle of Mohács. In 1527, Charles's mutinous[193] troops sacked Rome and took Pope Clement VII (r. 1523–1534) under custody. Luther stated that "Christ reigns in such a way that the emperor who persecutes Luther for the pope is forced to destroy the pope for Luther".[241]

After his experiences with radical communities, Luther no more wrote of the congregations' right to elect their ministers (or pastors). Instead, he expected that princes acting as "emergency bishops" would prevent the disintegration of the Church.[242] Close cooperation between clerics and princely officials at church visitations paved the way for the establishment of the new church system.[243] In Electoral Saxony, princely decrees enacted the Evangelical ideas.[244] Liturgy was simplified, the church courts' jurisdiction over secular cases was abolished, and state authorities took control of church property.[243] The Evangelical equivalent to bishop was created with the appointment of a former Catholic priest Johannes Bugenhagen (d. 1558) as superintendent in 1533.[244] The church visitations convinced Luther that the villagers' knowledge of the Christian faith was imperfect.[note 35] To deal with the situation, he completed two cathecisms—the Large Catechism for the education of priests, and the Small Catechism for children.[245] Records from Brandenburg-Ansbach indicates that Evangelical pastors often attacked traditional communal activities such as church fairs and spinning bees for debauchery.[246]

"In matters concerning God's honor and our soul's salvation everyone must stand before God and answer by himself, nobody can excuse himself in that place by the actions of decisions of others whether they be a minority or majority."

Taking advantage of Emperor Charles' victories in Italy, Ferdinand I achieved the reinforcement of the imperial ban against Luther at the Diet of Speyer in 1529. In response, five imperial princes and fourteen imperial cities[note 36] presented a formal protestatio. They were mocked as "Protestants", and this appellation would be quickly applied to all followers of the new theologies.[note 37][249] To promote Protestant unity, Philip the Magnanimous organised a colloquy (or theological debate) between Luther, Melanchton, Zwingli and Oecolampadius at Marburg early in October 1529,[250] but they could not coin a common formula on the Eucharist.[251] During the discussion, Luther remarked that "Our spirit has nothing in common with your spirit", expressing the rift between the two mainstream versions of the Reformation. Zwingli's followers started to call themselves the "Reformed", as they regarded themselves as the true reformers.[252]

Stalemate in Switzerland

[edit]In 1526, the villagers of the autonomous Graubünden region in Switzerland agreed that each village could freely choose between Protestantism and Catholicism, setting a precedent for the coexistence of the two denominations in the same jurisdiction.[253] Religious affiliation in the Mandated Territories (lands jointly administered by the Swiss cantons) became the subject of much controversy between Protestant and Catholic cantons. The Protestant cantons concluded a military alliance early in 1529, the Catholic cantons in April.[254][255] After a bloodless armed conflict, the Mandated communities were granted the right to choose between the two religions by a majority vote of the male citizens. Zwingli began an intensive proselityzing campaign which led to the conversion of most Mandated communities to Protestantism. He set up a council of clergymen and lay delegates for church administration, thus creating the forerunners of presbyteries.[256] Zürich imposed an economic blockade on the Catholic cantons but the Catholics routed Zürich's army in 1531. The Catholics' victory stopped the Protestant expansion in Switzerland.[255][257]

Zwingli was killed in the battlefield, and succeeded by a former monk Heinrich Bullinger (d. 1575) in Zürich. Bullinger developed Zwingli's Eucharistic formula in an attempt to reach a compromise with Luther, saying that the faithful made spiritual contact with God during the commemorative ceremony.[note 38][259]

Schleitheim Articles

[edit]

The historian Carter Lindberg states that the "Peasants' War was a formative experience for many leaders of Anabaptism".[260] Hans Hut (d. 1527) continued Müntzer's apocalypticism but others rejected all forms of violence.[261]

The pacifist Michael Sattler (d. 1527) took the chair at an Anabaptist assembly at Schleitheim in February 1527. Here the participants adopted an anti-militarist program now known as the Schleitheim Articles. The document ordered the believers' separation from the evil world, and prohibited oath-taking, bearing of arms and holding of civic offices. Facing Ottoman expansionism, the Austrian authorities considered this pacifism as a direct threat to their country's defense. Sattler was quickly captured and executed. During his trial, he stated that "If the Turks should come, we ought not to resist them. For it is written: Thou shalt not kill."[262][263]

Total segregation was alien to Hübmaier who tried to achieve a peaceful coexistence with non-Anabaptists.[264] Expelled from Zürich, he settled in the Moravian domains of Count Leonhard von Liechtenstein at Nikolsburg (now Mikulov, Czech Republic). He baptised infants on the parents' request for which hard-line Anabaptists regarded him as an evil compromiser. He was sentenced to death and burned at the stake for heresy on Ferdinand I's orders. His execution inaugurated a period of intensive purge against rebaptisers. His followers relocated to Austerlitz (now Slavkov u Brna, Czech Republic) where refugees from Tyrol joined them. After the Tyrolian Jakob Hutter (d. 1536) assumed the leadership of the community, they began to held their goods in common. The Bohemian Brethren symphatised with the Hutterites which facilitated their survival in Moravia.[265]

Confessions

[edit]

Back in Germany in January 1530, Charles V asked the Protestants to summarize their theology at the following Diet in Augsburg. As the imperial ban prevented Luther from attending the Diet, Melanchthon completed the task. Melanchthon sharply condemned Anabaptist ideas and adopted a reconciliatory tone towards Catholicism but did not fail to emphasize the most featuring elements of Evangelical theology, such as justification by faith alone. The twenty-eight articles of the Augsburg Confession were presented at the Diet on 25 June. Four south German Protestant cities—Strasbourg, Constance, Lindau, and Memmingen—adopted a separate confessional document, the Tetrapolitan Confession because they were influenced by Zwingli's Eucharistic theology. On Charles's request, Eck and other Catholic theologians completed a response to the Augsburg Confession, called Confutatio ('refutation'). Charles ordered the Evangelical theologians to admit that their argumentation had been completely refuted. Instead, Melanchthon wrote a detailed explanation for the Evangelical articles of faith, known as the Apology of the Augsburg Confession.[251][266]

Charles wanted to attack the Protestant princes and cities but the Catholic princes did not support him fearing that his victory would strengthen his power. The Diet passed a law prohibiting further religious innovations and ordering the Protestants to return to Catholicism until 15 April 1531. Luther had previously questioned the princes' right to resist imperial power, but by then he had concluded that a defensive war for religious purposes could be regarded as a just war.[267] The Schmalkaldic League—the Protestant Imperial Estates' defensive alliance—was signed by five princes and fourteen cities on 27 February 1531.[note 39] As a new Ottoman invasion prevented the Habsburgs from waging war against the Protestants, a peace treaty was signed at Nuremberg in July 1532.[269]

Royal Reformation in Scandinavia

[edit]Relationship between the papacy and the Scandinavian kingdoms was tense, as both Frederick I of Denmark and Norway, and Gustav I of Sweden appointed their own candidates to vacant episcopal sees.[270] In 1526, the Danish Parliament prohibited the bishops to seek confirmation from the Holy See, and declared all fees payable for their confirmation as royal revenue.[271] The former Hospitaller knight Hans Tausen (d. 1561) delivered Evangelical sermons in Viborg under royal protection from 1526. Four years later, the Parliament rejected the Catholic prelates' demand to condemn Evangelical preaching.[272] After Frederick's death the bishops and conservative aristocrats prevented the election of his openly Protestant son Christian as his successor.[273] Christopher, Count of Oldenburg (r. 1526–1566) took up arms on the deposed Christian II's behalf, but the war known as Count's Feud ended with the victory of Frederick's son who ordered the arrest of the Catholic bishops. Christian III (r. 1534–1559) was crowned king by Bugenhagen. Bugenhagen also ordained seven superintendents to lead the Church of Denmark. Christian declared the Augsburg Confession as the authoritative articles of faith in 1538,[274] but pilgrimages to the most popular shrines continued, and the Eucharistic liturgy kept Catholic elements, such as kneeling.[275]

In the Danish dependencies of Norway and Iceland, the Reformation required vigorous governmental interventions.[276] The last Catholic Archbishop of Nidaros in Norway Olav Engelbrektsson (d. 1538) was a staunch opponent of the changes, but was succeeded by the Evangelical Gjeble Pederssøn (d. 1557) as superintendent.[277] In Iceland, Jón Arason, Bishop of Hólar (d. 1550)—the last Nordic Catholic bishop—took up arms to prevent the Reformation, but he was captured and executed by representatives of royal authority.[note 40][279]

Gustav I of Sweden appointed the Evangelical preacher Laurentius Andreae (d. 1552) as his chancellor, and the Evangelical scholar Olaus Petri (d. 1552) as a minister at Stockholm. Petri translated the Gospels to Swedish. On his advice, Gustav dissolved a Catholic printing house that published popular anti-Protestant literature under the auspices of Hans Brask (d. 1538), Bishop of Linköping. Gustav also expelled the radical German pastor Melchior Hoffman (d. c. 1543) from Sweden for iconoclastic propaganda.[280][281] The royal treasury needed extra funds to repay the loans borrowed from the Hanseatic League to finance the war against Christian II. Gustav persuaded the legislative assembly to secularise church property by threatening the delegates with his abdication.[281] The peasantry remained very cautious about changes in church life. This together with heavy taxation led to uprisings. To appease the rebels, Gustav declared that he had not sanctioned the changes, and dismissed Andreae in 1531, Petri in 1533.[282] He continued the transformation of church life in Sweden and Finland after the Reformation was fully introduced in Denmark. He was assisted by two Evangelical theologians Georg Norman (d. 1552/1553) and Mikael Agricola (d. 1557).[283] In 1539, Norman was appointed as supertindent of the Church of Sweden, and Gustav took the title of "Supreme Defender of the Church".[284]

Catholic reform

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]The religious upheaval in Germany and the sack of Rome (1527) further convinced many Catholics that the Church was in need of a profound reform. Pope Paul III (r. 1534–1549) appointed prominent representatives of the Catholic reform movement as cardinals, among them Contarini, Reginald Pole (d. 1558), and Giovanni Pietro Caraffa (d. 1559). They completed a report condemning the corruption of church administration and the waste of church revenues.[note 41] Contarini, Pole and other Spirituali were ready to make concessions to the Protestants but their liberalism shocked Caraffa and other conservative prelates.[286]

Negotiations between moderate Catholic and Protestant theologians were not unusual. In 1541, Bucer and the Catholic theologian Johann Gropper (d. 1559) drafted a compromise formula on justification.[note 42] The draft was discussed along with other issues at a colloquy during the Diet of Regensburg but no compromise was reached, not least due to opposition by both Luther and the Holy See.[287] Contarini, who represented the papacy at the Diet, died in 1541; many Spirituali such as Vermigli fled from Italy to avoid persecution.[288] Hermann of Wied, Archbishop-elector of Cologne (r. 1515–1546) completed a reform program with Bucer's assistance, criticising prayers to the saints and traditional Eucharistic theology, and proposing sermons about justification by faith.[289] The canons of the Cologne Cathedral requested Gropper to write a critical response to it,[290] and achieved Hermann's deposal by the Roman Curia.[291]

New Orders

[edit]

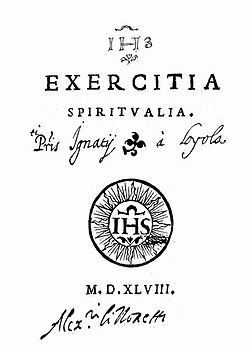

The spread of new monastic orders was an important element of the Catholic reform movement. Most new orders placed great value on pastoral care.[note 43] Among them, the Society of Jesus (or Jesuits) became the most influential.[294] Its founder Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556) was born to a Basque noble family. He chose a military career but abandoned it after being wounded during a siege. He started to write a devotional guide, the Spiritual Exercises, during his ascetic retreat at a cave.[295] His mysticism arouse the Spanish Inquisition's suspicion but the Spirituali supported him. Paul III sanctioned the establishment of the Jesuits on Contarini's influence in 1540.[296] The new order quickly developed: when Loyola died, the Society had about 1,000 members; in less than a decade, it numbered around 3,500. The maintenance of a well organised schooling system was the Jesuits' most prominent feature. Their Roman collegium prepared future priests to discuss and reject Protestant theologies primarily in Germany, Bohemia, Poland, and Hungary.[297]

Council of Trent

[edit]Paul III decided to convoke the nineteenth ecumenical council to handle the crisis caused by the Reformation. The Council of Trent met in a series of sessions from December 1545 to 1548, 1521 to 1522, and 1562 to 1563.[note 44][298] The topics dealt with included the Creed, the Sacraments including transubstantiation and ordination,[299] justification, and improvement in the quality of priests by diocesan seminaries and annual canonical visitations.[300] The council reaffirmed that apostolic tradition was as authentic a source of faith as the Bible, and emphasized the importance of good works in salvation,[note 45] rejecting two important elements of Luther's theology.[302] Before being closed in December 1563, the Council mandate the papacy to revise liturgical books and complete a new catechism.[303] Carlo Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan (d. 1582) adopted a more practical approach. He completed a handbook covering everyday details of church life, including the delivery of sermons, arrangement of church interiors, and hearing confessions.[304] After the council, papal authority was reinforced through the establishment of central offices known as congregations. One of them became responsible for the list of forbidden literature. All church officials and university teachers were required to take a Tridentine confessional oath that included an oath of "true obedience" to the papacy.[305]

Lindberg suggests that (following Trent) the "spirituality of Catholic reform was the ascetic, subjective, and personal piety", as expressed in public processions, the "perpetual" adoration of the Eucharist, and the reaffirmed veneration of Mary the Virgin and the saints.[306]

New waves

[edit]English reformation under Henry VIII

[edit]

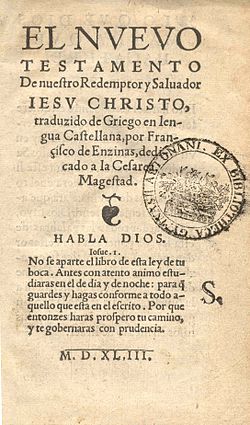

In England, reformist clerics such as Thomas Bilney (d. 1531) and Robert Barnes (d. 1540) spread Luther's theology among Cambridge and Oxford scholars and students.[307] The young priest William Tyndale (d. 1536) translated the New Testament to English using Erasmus's Latin-Greek edition.[308] By around 1535, more than 15,000 copies of his translation had been distributed in secret.[309] Tyndale's biographer David Daniell (d. 2016) writes that the translation "gave the English language a plain prose style of the very greatest importance", and his "influence has been greater than any other writer in English".[310]

The Lord Chancellor Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (d. 1530) had strong links to the Roman Curia, he was unable to achieve the annulment of the marriage of Henry VIII and the middle-aged Catherine of Aragon (d. 1536).[note 46][312] They had needed a papal dispensation to marry because Catherine was the widow of Henry's brother Arthur, Prince of Wales (d. 1502). As she had not produced a male heir, Henry became convinced that their incestuous marriage drew the wrath of God.[313]

Henry charged a group of scholars including Thomas Cranmer (d. 1556) with collecting arguments in favour of the annulment. They concluded that the English kings had always had authority over the clergy, and the Book of Leviticus forbade marriage between a man and his brother's widow in all circumstances.[314] In 1530, the Parliament limited the jurisdiction of church courts. Wolsey had meanwhile lost Henry's favour and died, but More tried to convince Henry to abandon his plan about the annulment of his marriage. In contrast, Cranmer and Henry's new chief advisor Thomas Cromwell (d. 1540) argued that the marriage could be annulled without papal interference.[311] Henry who had fallen in love with Catherine's lady-in-waiting Anne Boleyn (d. 1536) decided to marry her even if the marriage could lead to a total break with the papacy.[315] During a visit in Germany, Cranmer married but kept his marriage in secret. On his return to England, Henry appointed him as the new Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Holy See confirmed the appointment.[316]

The links between the English Church and the papacy were severed by Acts of Parliament.[note 47][318] In April 1533, the Act of Appeals decreed that only English courts had jurisdiction in cases of last wills, marriages and grants to the Church, emphasizing that "this realm of England is an Empire".[319][320] A special church court annulled the marriage of Henry and Catherine, and declared their only daughter Mary (d. 1558) illegitimate in May 1533.[321] Pope Clement VII did not sanction the judgement and excommunicated Henry.[322] Ignoring the papal ban, Henry married Anne, and she gave birth to a daughter Elizabeth (d. 1603).[323] Anne was a staunch supporter of the Reformation, and mainly her nominees were appointed to the vacant bishoprics between 1532 and 1536.[316] In 1534, the Act of Supremacy declared the king the "only supreme head of the Church of England".[318] Many of those who refused to swear a special oath of loyalty to the king—65 from about 400 defendants—were executed. More and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester (d. 1535) were among the most prominent victims.[323] Cromwell gradually convinced Henry that a "purification" of church life was needed. The number of feast days was reduced by about 75 per cent, pilgrimages were forbidden, all monasteries were dissolved and their property was seized by the Crown.[309]

The Parliament of Ireland passed similar acts but they could only be fully implemented in the lands under direct English rule. Resistance against the Reformation was vigorous. In 1534, the powerful Lord Thomas FitzGerald (d. 1537) staged a revolt. Although it was crushed, thereafter Henry's government did not introduce drastic changes in the Church of Ireland.[324] In England, the dissolution of monasteries caused a popular revolt known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. The "pilgrims" demanded the dismissal of "heretic" royal advisors but they were overcame by royalist forces.[325][326] The principal articles of faith of the Church of England were summarized in the Six Articles in 1539. It reaffirmed several elements of traditional theology, such as transubstantiation and clerical celibacy.[327]

As Anne Boleyn did not give birth to a son, she lost Henry's favour. She was executed for adultery, and Elizabeth was declared a bastard. Henry's only son Edward (d. 1553) was born to Henry's third wife Jane Seymour (d. 1537). In 1543, an Act of Parliament returned Mary and Elizabeth to the line of the succession behind Edward.[328][329] Henry attacked Scotland to enforce the marriage of Edward and the infant Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542–1567) but her mother Mary of Guise (d. 1560) reinforced Scotland's traditional alliance with France.[330] The priest George Wishart (d. 1546) was the first to preach Zwinglian theology in Scotland. After he was burned for heresy, his followers, among them John Knox (d. 1572), assassinated Cardinal David Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews (d. 1546), but French troops crushed their revolt.[331]

Münster

[edit]

Having been banished from Sweden, Hoffman was wandering in southern Germany and the Low Countries. He turned Anabaptist[332] but suspended adult baptism to avoid persecution.[333] He denied that Christ had become flesh,[note 48] and preached that 144,000 elect were to gather in Strasbourg to witness Christ's return in 1533.[332] His followers known as Melchiorites swarmed into the city, presenting an enormous challenge for its charity provisions. Hoffman also came to Strasbourg, but the authorities arrested him. After the deadline for Christ's return passed uneventfully, many disappointed Melchiorites accepted the leadership of a charismatic Dutch baker Jan Matthijszoon (d. 1534). He blamed Hoffman for the suspension of adult baptism, and proclaimed the city of Münster as the New Jerusalem. Although Münster was an episcopal see, the town council had installed a Protestant pastor Bernhard Rothmann (d. c. 1535) in clear defiance to the new prince-bishop Franz von Waldeck (r. 1532–1553). Those who expected a radical social transformation from the Reformation flocked to Münster. The radicals assumed full control of the town in February 1534.[335]

Bishop Franz and his allies, among them Philip of Hessen, attacked Münster but could not capture it. Under Matthijszoon's rule, private property and the use of money was outlawed in the town. Believing that God would protect him, Matthijszoon made a sortie against the enemy, but he was killed. Another charismatic Dutchman, John of Leiden (d. 1536)—a former tailor—succeeded him. Leiden announced that he was receiving revelations from God, and proclaimed himself "king of righteousness" and "the ruler of the new Zion". Church and state were united, and all sinners were executed.[336] Leiden legalized polygyny, and ordered all women who were twelve or older to marry. The protracted siege demoralized the defenders, and Münster fell through treason on 25 June 1535. After the fall of Münster, most Anabaptist groups adopted a pacifist approach under the leadership of a former priest Menno Simons (d. 1561).[337] He associated the Anabaptist communities with the New Jerusalem. His followers would be known as Mennonites.[338] Nearly all Anabaptist communities were destroyed in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland,[339] but moderate Anabaptist groups survived in East Frisia,[340] and were mainly tolerated in England.[341]

Calvin and the Institutes of the Christian Religion

[edit]

The future reformer John Calvin (d. 1564) was destined to a church career by his father, a lay administrator of the Bishopric of Noyon in France.[note 49] He studied theology at the Sorbonne, and law at Orléans and Bourges. He read treatises by Lefèvre and Lefèvre's disciples at the newly established Collège Royal, and abandoned Catholicism under the influence of his Protestant friends, particularly the physician Nicolas Cop (d. 1540).[343] The persecution of French Protestants intensified after the so-called Affair of the Placards. In October 1534, placards (or posters) attacking the Mass were placed at many places, including the door to the royal bedchamber in Château d'Amboise. In retaliation, twenty-four Protestants were executed, and many intellectuals had to leave France.[344]

Calvin was one of the French religious refugees. He settled in Basel and completed the first version of his principal theological treatise, the Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1536. He would be rewriting and expanding it several times until 1559. As the historian Carlos Eire writes, "Calvin's text was blessed with a lawyer's penchant for precision, a humanist's love for poetic expression and rhetorical flourishes, and a theologian's respect for paradox".[345] With Eire's words, Calvin "revived the jealous God of the Old Testament". He warned French King Francis I that the persecution of the faithful would incur the wrath of God upon him but sharply distanced moderate Protestants from Anabaptists.[note 50][347][348] Already the first edition of the Institutes contained references to two distinguishing elements of Calvin's theology, both traceable back to Augustine: his conviction that the original sin had completely corrupted human nature, and his strong belief in "double predestination". In his view, only strict social and ecclesiastic control could prevent sins and crimes,[349] and God did not only decide who were saved but also those who were destined to damnation.[350][351]

In 1536, Farel convinced Calvin to settle in Geneva. Their attempts to implement radical reforms in discipline brought them into conflicts with those who feared that the new measures would lead to clerical despotism.[352] After they refused to acknowledge the urban magistrates' claim to intervene in the process of excommunication, they were banished from the town. Calvin moved to Strasbourg where Bucer made a profound impact on him.[353] Under Bucer's influence, Calvin adopted an intermediate position on the Eucharist between Luther and Zwingli, denying Christ's presence in it but acknowledging that the rite included a real spiritual communion with Christ.[353]

No one who wishes to be thought religious dares simply deny predestination, by which God adopts some to hope of life, and sentences others to eternal death...For all are not created in an equal condition; rather eternal life is fore-ordained for some, eternal damnation for others.

After Calvin and Farel left Geneva, no pastors were able to assume the leadership of the local Protestant community. Fearing of a Catholic restoration, the urban magistrates convinced Calvin to come back to Geneva in 1541. Months after his return, the town council enacted The Ecclesiastical Ordinances, a detailed regulation summarizing Calvin's proposals for church administration.[355] The Ordinances established four church offices. The pastors were responsible for pastoral care and discipline; the doctors instructed believers in the faith; the elders (or presbyters) were authorized to "watch over the life of each person" and to report those who lived a "disorderly" life to the pastors; and deacons were appointed to administer the town's charity. All townspeople were obliged to regularly attend church services. Calvin established a special court called the consistory to hear cases of moral lapse such as blasphemy, adultery, disrespect to authorities, gossiping, witchcraft and participation in rites considered superstitious by church authorities. The consistory was composed of the pastors, the elders, and an urban magistrate, and the townspeople were encouraged to report sinful acts to it. First-time offenders mainly received lenient sentences such as fines, but repeat offenders were banished from the town or executed.[356] Resistance against the Ordinances was significant. Many continued visit shrines and pray to saints, while many patricians insisted on liberal traditional customs for which Calvin called them "Libertines".[357]

Reformation in Britain