Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

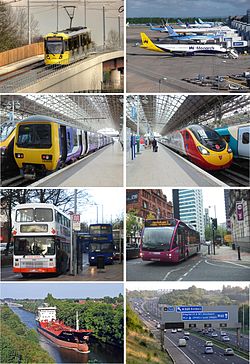

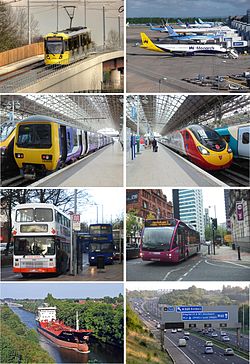

Transport

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Transport |

|---|

| Modes |

| Overview |

| Topics |

|

|

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipelines, and space. The field can be divided into infrastructure, vehicles, and operations. Transport enables human trade, which is essential for the development of civilizations.

Transport infrastructure consists of both fixed installations, including roads, railways, airways, waterways, canals, and pipelines, and terminals such as airports, railway stations, bus stations, warehouses, trucking terminals, refueling depots (including fuel docks and fuel stations), and seaports. Terminals may be used both for the interchange of passengers and cargo and for maintenance.

Means of transport are any of the different kinds of transport facilities used to carry people or cargo. They may include vehicles, riding animals, and pack animals. Vehicles may include wagons, automobiles, bicycles, buses, trains, trucks, helicopters, watercraft, spacecraft, and aircraft.

Modes

[edit]A mode of transport is a solution that makes use of a certain type of vehicle, infrastructure, and operation. The transport of a person or of cargo may involve one mode or several of the modes, with the latter case being called inter-modal or multi-modal transport.[1] Each mode has its own advantages and disadvantages, and will be chosen on the basis of cost, capability, and route.[2]

Governments regulate the way the vehicles are operated, and the procedures set for this purpose, including financing, legalities, and policies.[3] In the transport industry, operations and ownership of infrastructure can be public, private, or a partnership between the two, depending on the country and mode.[4][5] Transport modes can be a mix of the two ownership systems, such as privately owned cars and government-owned urban transport in cities.[6] Many international airlines have a mixed public-private ownership.[7]

Passenger transport may be public, where operators provide scheduled services, or private.[8] Freight transport has become focused on containerization, although bulk transport is used for large volumes of durable items.[9] Transport plays an important part in economic growth and globalization,[10][11] but machine-propelled forms cause air pollution and use large amounts of land.[12] While it[vague] is heavily subsidized by governments, good planning of transport is essential to make traffic flow and restrain urban sprawl.

Human-powered

[edit]

Human-powered transport, a form of sustainable transport, is the transport of people or goods using human muscle-power, in the form of walking,[14] running, and swimming. Technology has allowed machines to improve the energy efficiency of human mobility on relatively smooth terrain.[15] Human-powered transport remains popular for reasons of cost-saving, leisure, physical exercise, and environmentalism;[16] it is sometimes the only type available, especially in underdeveloped or inaccessible regions.

Although humans are able to walk without infrastructure, the accessibility can be enhanced through the use of roads, sidewalks, and shared-use paths, especially when using the human power with vehicles, such as bicycles, inline skates, and wheelchairs.[17] Human-powered vehicles have been developed for difficult environments, such as snow and water, by watercraft rowing and skiing;[18][19] even the air can be flown through with human-powered aircraft.[20] Personal transporters, a form of hybrid human-electric powered vehicle, have emerged in the 21st century as a form of multi-model urban transport.[21]

Animal-powered

[edit]

Animal-powered transport is the use of working animals for the movement of people and commodities.[22] Humans may ride some of the animals directly, use them as pack animals for carrying goods, or harness them,[23] alone or in teams, to pull sleds or wheeled vehicles. They remain useful in rough terrain that is not readily accessible by automotive-based transportation.[22]

Air

[edit]

A fixed-wing aircraft, commonly called an airplane, is a heavier-than-air craft where movement of the air in relation to the wings is used to generate lift. The term is used to distinguish this from rotary-wing aircraft, where the movement of the lift surfaces relative to the air generates lift.[24] A gyroplane is both fixed-wing and rotary wing.[citation needed] Fixed-wing aircraft range from small trainers and recreational aircraft to large airliners and military cargo aircraft.

Two things necessary for aircraft are air flow over the wings for lift and an apparatus for landing. The majority of aircraft require an airport with the infrastructure for maintenance, restocking, and refueling and for the loading and unloading of crew, cargo, and passengers.[25] Many aerodromes have takeoff and landing restrictions on weight and runway length, and so are not able to handle all types of aircraft.[26] While the vast majority of fixed-wing aircraft land and take off on land, some are capable of take-off and landing on ice, snow,[27] and calm water.[28]

Autonomous or remotely-piloted airplanes are known as unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAV. These drones can range in size from less than a metre across to a full-sized airplane.[29] They are capable of carrying a payload, and are being used for package delivery.[30]

The aircraft is the second fastest method of transport, after the rocket. Commercial jets can reach up to 955 kilometres per hour (593 mph), single-engine aircraft 555 kilometres per hour (345 mph). Aviation is able to quickly transport people and limited amounts of cargo over longer distances, but incurs high costs and energy use; for short distances or in inaccessible places, helicopters can be used.[31] As of April 28, 2009, The Guardian article notes that "the WHO estimates that up to 500,000 people are on planes at any time."[32]

An aerostat is a class of lighter-than-air aircraft that gains its lift by containing a volume of gas that has a lower density than the surrounding atmosphere. These include balloons and rigid, semi-rigid, or non-rigid airships; the last is called a blimp. The lifting gas is typically helium, as hydrogen is highly flammable. Alternatively, heated air is used in hot air balloons and thermal airships. Aerostats can transport passengers and a payload over long distances. For example, zeppelins were used on long-ranged bombing raids during World War I.[33]

Land

[edit]Land transport covers all land-based transport systems that provide for the movement of people, goods, and services. Land transport plays a vital role in linking communities to each other. Land transport is a key factor in urban planning. It consists of two kinds, rail and road.

Rail

[edit]

Rail transport consists of wheeled vehicles running on tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails, known as a railway or railroad. The rails are anchored perpendicular to ties (or sleepers) of timber, concrete, or steel, to maintain a consistent distance apart, or gauge. The rails and perpendicular beams are placed on a foundation made of concrete or compressed earth and gravel in a bed of ballast.[34] Alternative methods include monorail,[35] maglev, and hyperloop.[36] Dual gauge railways have three or four rails, allowing use by trains with two or three track gauges.[37] For steep grades, a railway can use an additional toothed rack rail for traction.[38]

A train consists of one or more connected vehicles that operate on the rails, known as rolling stock. Propulsion is commonly provided by a locomotive, which hauls a series of unpowered cars that carry passengers or freight. The locomotive can be powered by steam, diesel,[39] gas turbine,[40] or else electricity supplied by trackside systems. Some or all the cars can be powered, known as a multiple unit.[39] A tram is similar to a train, but is generally smaller, travels shorter distances, and runs on rails that are integrated into the streets. Typically a tram is electric-powered, but they have also been propelled by horses, cables,[41] gravity,[citation needed] or pneumatics.[42] Railed vehicles move with much less friction than rubber tires on paved roads, making trains more energy efficient, though not as efficient as ships.[43]

Intercity trains are long-haul services connecting cities;[44] modern high-speed rail is capable of speeds up to 350 km/h (220 mph), but this requires specially built track. Commercial maglev transport in Shanghai runs at 460 km/h (290 mph).[45] Regional and commuter trains feed cities from suburbs and surrounding areas, while intra-urban transport is performed by high-capacity tramways and rapid transits,[46] in many cases making up the backbone of a city's public transport.[citation needed] Freight trains traditionally used box cars, requiring manual loading and unloading of the cargo. Since the 1980s, container trains have become the dominant solution for general freight,[47] while large quantities of bulk are transported by dedicated rolling stock. An example of the latter are specially designed tank cars for the transport of hazardous materials.[48]

Road

[edit]

A road is an identifiable route, way, or path between two or more places.[49] Roads are typically smoothed, paved, or otherwise prepared to allow easy travel;[50] though they need not be, and historically many roads were simply recognizable routes without any formal construction or maintenance.[51] In urban areas, roads may pass through a city or village and be named as streets, serving a dual function as urban space easement and route.[52]

At least within the U.S., the most common road vehicle is the automobile;[53] a light duty wheeled passenger vehicle that carries its own motor. Other users of roads include buses, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, and pedestrians. As of 2015, there were 950 million passenger cars worldwide, with a projected total of 2.5 billion in 2050.[54] Road transport offers road users the flexibility to transfer the vehicle from one lane to the other and from one road to another according to the need and convenience. This combination of changes in location, direction, speed, and timings of travel is not available to other motorized modes of transport.[55] It is possible to provide efficient intracity door-to-door service only by road transport.

Some drawbacks are that a road system consumes large amounts of space, are costly to build and maintain (including vehicles), leads to urban congestion, and have only limited ability to achieve economies of scale.[55] Automobiles provide high flexibility with low capacity, but require high energy and area use, and are the main source of harmful noise and air pollution in cities;[56] buses allow for more efficient travel at the cost of reduced flexibility.[44] Road transport by truck is often the initial and final stage of freight transport.[55]

Water

[edit]

Water transport is movement by means of a watercraft—such as a barge, boat, ship, or sailboat—over a body of water, such as a sea, ocean, lake, canal, or river. The need for buoyancy is common to watercraft,[57] making the hull a critical aspect of its construction, maintenance, and appearance.

In the 19th century, the first steam ships were developed, using a steam engine to drive a paddle wheel or propeller to move the ship. The steam was produced in a boiler using wood or coal and fed through a steam external combustion engine.[58] Now most commercial ships have an internal combustion engine using a slightly refined type of petroleum called bunker fuel.[59] Some ships, such as submarines, use nuclear marine propulsion with heat from a nuclear reactor generating the steam.[60] Recreational or educational craft still use wind power or oars, while some smaller craft use internal combustion engines to drive one or more propellers or, in the case of jet boats, an inboard water jet.[61] In shallow draft areas, hovercraft are propelled by large pusher-prop fans.[62] (See Marine propulsion.)

Although it is slow compared to other transport, modern sea transport is a highly efficient method of transporting large quantities of goods. Commercial vessels, nearly 35,000 in number, carried 7.4 billion tons of cargo in 2007.[63] Transport by water is significantly less costly than air transport for transcontinental shipping;[64] short sea shipping and ferries remain viable in coastal areas.[65][66]

Other modes

[edit]

Pipeline transport sends goods through a pipe; most commonly, chemically-stable liquids, vapors, and gases can be sent,[67] while a slurry can be used to transport solids.[68] Pneumatic tubes can send solid capsules using compressed air.[69] Short-distance systems exist for sewage, slurry, water, and beer, while long-distance networks are used for freshwater,[70][71] petroleum, and natural gas.[72]

Cable transport is a broad mode where vehicles are pulled by cables instead of an internal power source. It is most commonly used at steep gradient.[73] Typical solutions include aerial tramways,[74] funiculars, elevators,[75] material ropeways,[76] and ski lifts;[73] some of these are also categorized as conveyor transport.[citation needed] A variant is the zip line, which uses gravity for propulsion.[77]

Spaceflight is transport outside Earth's atmosphere by means of a spacecraft. It is most frequently used for satellites placed in Earth orbit.[78] However, human spaceflight mission have landed on the Moon[79] and are occasionally used to rotate crew-members to space stations.[80] Uncrewed spacecraft have been sent to all the planets of the Solar System.[81]

Suborbital spaceflight is the fastest of the existing and planned transport systems from a place on Earth to a distant "other place" on Earth.[82] These rocket-propelled systems could potentially do global point-to-point transport delivery of passengers or cargo in less than 90 minutes.[83]

Elements

[edit]Infrastructure

[edit]

Infrastructure is the fixed installations that allow a vehicle to operate. It consists of a transport network, a terminal, and facilities for parking and maintenance.[84] For rail, pipeline, road, and cable transport, the entire way the vehicle travels must be constructed. Air and watercraft are able to avoid this, since the airway and seaway do not need to be constructed. However, they require fixed infrastructure at terminals.[85]

Terminals such as airports, ports, and stations, are locations where passengers and freight can be transferred from one vehicle or mode to another. For passenger transport, terminals are integrating different modes to allow riders, who are interchanging between modes, to take advantage of each mode's benefits[85]. For instance, airport rail links connect airports to the city centres and suburbs. The terminals for automobiles are parking lots, while buses and coaches can operate from simple stops.[86] For freight, terminals act as transshipment points,[87] though some cargo is transported directly from the point of production to the point of use.

The financing of infrastructure can either be public or private. Transport is often a natural monopoly[88] and a necessity for the public; roads, and in some countries railways and airports, are funded through taxation. New infrastructure projects can have high costs and are often financed through debt. Many infrastructure owners, therefore, impose usage fees,[citation needed] such as landing fees at airports or toll plazas on roads.[89] Independent of this, authorities may impose taxes on the purchase or use of vehicles.[90] Because of poor forecasting and overestimation of passenger numbers by planners, there is frequently a benefits shortfall for transport infrastructure projects.[91]

Means of transport

[edit]Animals

[edit]Animals used in transportation include pack animals and riding animals. These include various bovids, equids, and camelids; animal families noted for their muscular strength.[92] Other species employed for various forms of transport include the dog, elephant, ostrich, sheep, and even the dolphin.[93]

Vehicles

[edit]

A vehicle is a non-living device that is used to move people and goods. Unlike the infrastructure, the vehicle moves along with the cargo and riders. Unless being pulled/pushed by a cable or muscle-power, the vehicle must provide its own propulsion; this is most commonly done through a steam engine, combustion engine, electric motor,[94] jet engine, or rocket,[95] though other means of propulsion also exist such as sail power or compressed air.[96] Vehicles also need a system of converting the energy into movement; this is most commonly done through wheels, propellers, and air pressure.[97]

Vehicles are commonly staffed by a driver. However, some systems, such as people movers and some rapid transits, are fully automated.[98] For passenger transport, the vehicle must have a compartment, seat, or platform for the passengers. Simple vehicles, such as automobiles, bicycles, or simple aircraft, may have one of the passengers as a driver. Since 2016, progress related to the Fourth Industrial Revolution has brought a lot of new emerging technologies for transportation and automotive fields such as connected vehicles[99] and autonomous vehicles.[100] These innovations are said to form future mobility, but concerns remain on safety and cybersecurity, particularly concerning connected and autonomous mobility.[101]

Operation

[edit]

Private transport is only subject to the owner of the vehicle, who operates the vehicle themselves. For public transport and freight transport, operations are done through private enterprise, governments, or a partnership between the two.[102][4] The infrastructure and vehicles may be owned and operated by the same company, or they may be operated by different entities. Traditionally, many countries have had a national airline and national railway. Since the 1980s, many of these have been privatized.[103] International shipping remains a highly competitive industry with little regulation,[104] but ports can be public-owned.[105]

Policy

[edit]As the population of the world increases, cities grow in size and population—according to the United Nations, 55% of the world's population live in cities, and by 2050 this number is expected to rise to 68%.[106] Public transport policy must evolve to meet the changing priorities of the urban world.[107] The institution of policy enforces a degree of order in transport, which is by nature chaotic as people attempt to travel from one place to another as rapidly as possible.[108] This policy helps to reduce accidents and save lives.

Functions

[edit]Relocation of travelers and cargo are the most common uses of transport. However, other uses exist, such as the transfer of mobile construction and emergency equipment, or the strategic and tactical relocation of armed forces during warfare.

Passenger

[edit]

Passenger transport, or travel, is divided into public and private transport. Public transport is scheduled services on fixed routes, while private service can be scheduled (e.g. commercial airlines) or chartered (e.g. shipping) or can provide ad hoc services at the riders desire (e.g. taxi).[102] The latter offers better flexibility, but has lower capacity and a higher environmental impact. Travel may be as part of daily commuting or for business, leisure, or migration.[109]

Short-haul transport is dominated by the automobile and mass transit. The latter consists of buses in rural and small cities, supplemented with commuter rail, trams, and rapid transit in larger cities.[102] Long-haul transport involves the use of the automobile, trains, ships, coaches, and aircraft,[110] the last of which have become predominantly used for the longest, including intercontinental, travel. Intermodal passenger transport is where a journey is performed through the use of several modes of transport; since all human transport normally starts and ends with walking, all passenger transport can be considered intermodal.[111] Public transport may also involve the intermediate change of vehicle, within or across modes, at a transport hub, such as a bus or railway station.[112]

Taxis and buses can be found on both ends of the public transport spectrum. Buses are the cheapest mode of transport but are not necessarily flexible, and taxis are very flexible but more expensive.[113] In the middle is demand-responsive transport, offering flexibility whilst remaining affordable.

International travel may be restricted for some individuals due to legislation and visa requirements.[114]

Medical

[edit]

An ambulance is a vehicle used to transport people from or between places of treatment,[115] and in some instances will also provide out-of-hospital medical care to the patient. The word is often associated with road-going "emergency ambulances", which form part of emergency medical services, administering emergency care to those with acute medical problems.

Air medical services is a comprehensive term covering the use of air transport to move patients to and from healthcare facilities and accident scenes. Personnel provide comprehensive prehospital and emergency and critical care to all types of patients during aeromedical evacuation or rescue operations, aboard helicopters, propeller aircraft, or jet aircraft.[116][117]

Freight

[edit]

Freight transport, or shipping, is a key in the value chain in manufacturing.[118] With increased specialization and globalization, production is being located further away from consumption, rapidly increasing the demand for transport.[119] Transport creates place utility by moving the goods from the place of production to the place of consumption.[120] While all modes of transport are used for cargo transport, there is high differentiation between the nature of the cargo transport, in which mode is chosen.[121] Logistics refers to the entire process of transferring products from producer to consumer, including storage, transport, transshipment, warehousing, material-handling, and packaging, with associated exchange of information.[122] Incoterm deals with the handling of payment and responsibility of risk during transport.[123]

Containerization, with the standardization of ISO containers on all vehicles and at all ports, has revolutionized international and domestic trade, offering a huge reduction in transshipment costs. Traditionally, all cargo had to be manually loaded and unloaded into the haul of any ship or car; containerization allows for automated handling and transfer between modes, and the standardized sizes allow for gains in economy of scale in vehicle operation. This has been one of the key driving factors in international trade and globalization since the 1950s.[124]

Bulk transport is common with cargo that can be handled roughly without significant deterioration; typical examples are ore, coal, cereals, and petroleum.[125] Because of the uniformity of the product, mechanical handling can allow enormous quantities to be handled quickly and efficiently. The low value of the cargo combined with high volume also means that economies of scale become essential in transport, and gigantic ships and whole trains are commonly used to transport bulk. Liquid products with sufficient volume may also be transported by pipeline.

Air freight has become more common for products of high value; while less than one percent of world transport by volume is by airline, it amounts to forty percent of the value. Time has become especially important in regards to principles such as postponement and just-in-time within the value chain, resulting in a high willingness to pay for quick delivery of key components or items of high value-to-weight ratio.[126] In addition to mail, common items sent by air include electronics and fashion clothing.

Industry

[edit]Impact

[edit]In the three-sector model of economics, transportation is a component of the tertiary sector that provides services for a functioning economy. Thus, the inefficiency and malfunctioning of transport creates an economic impact. Even when functioning effectively, the operation of a transportation network can have an adverse effect on the environment and human safety. For example, road traffic accidents are one of the leading causes of death world-wide, killing or injuring nearly 1.35 million people every year.[127] The planning, design, maintenance, and operation of facilities for different transport modes is performed through transportation engineering. Their goal is to provide for the safe, efficient, rapid, comfortable, convenient, economical, and environmentally compatible movement of people and goods transport.[128]

Economic

[edit]

Transport is a key necessity for specialization—allowing production and consumption of products to occur at different locations. Throughout history, transport has been a spur to expansion; better transport allows more trade and a greater spread of people. Economic growth has always been dependent on increasing the capacity and rationality of transport.[129] But the infrastructure and operation of transport have a great impact on the land, and transport is the largest drainer of energy, making transport sustainability a major issue.

Due to the way modern cities and communities are planned and operated, a physical distinction between home and work is usually created, forcing people to transport themselves to places of work, study, or leisure, as well as to temporarily relocate for other daily activities.[130] Passenger transport is the essence of tourism, a major part of recreational transport. Commerce requires the transport of people to conduct business, either to allow face-to-face communication for important decisions or to move specialists from their regular place of work to sites where they are needed.

In lean thinking, transporting materials or work in process from one location to another is seen as one of the seven wastes (Japanese term: muda) which do not add value to a product.[131]

Planning

[edit]Transport planning allows for high use and less impact regarding new infrastructure. Using models of transport forecasting, planners are able to predict future transport patterns.[132] On the operative level, logistics allows owners of cargo to plan transport as part of the supply chain.[133] Transport as a field is studied through transport economics, a component for the creation of regulation policy by authorities.[citation needed] Transport engineering, a sub-discipline of civil engineering, must take into account trip generation, trip distribution, mode choice, and route assignment,[134] while the operative level is handled through traffic engineering.

Because of the negative impacts incurred, transport often becomes the subject of controversy related to choice of mode, as well as increased capacity. Automotive transport can be seen as a tragedy of the commons, where the flexibility and comfort for the individual deteriorate the natural and urban environment for all.[135] Density of development depends on mode of transport, with public transport allowing for better spatial use. Good land use keeps common activities close to people's homes and places higher-density development closer to transport lines and hubs, to minimize the need for transport. There are economies of agglomeration.[136] Beyond transport, some land uses are more efficient when clustered. Transport facilities consume land, and in cities pavement (devoted to streets and parking) can easily exceed 20 percent of the total land use.[137] An efficient transport system can reduce land waste.

Too much infrastructure and too much smoothing for maximum vehicle throughput mean that in many cities there is too much traffic and many—if not all—of the negative impacts that come with it.[citation needed] It is only in recent years[when?] that traditional practices have started to be questioned in many places; as a result of new types of analysis which bring in a much broader range of skills than those traditionally relied on—spanning such areas as environmental impact analysis, public health, sociology, and economics—the viability of the old mobility solutions is increasingly being questioned.[citation needed]

Safety

[edit]The energy levels involved in a transport accident can pose a significant risk for crew and passengers,[138] making safety an issue of importance to governments.[139] Significant accidents involve a review by law enforcement and independent investigators from a safety board,[140] such as the NTSB in the U.S. Measures and methods have been implemented to improve the safety of roads, automobiles, motorcycles, bicycles, railways, ships, and aircraft.[141] There are emergency medical services and sea rescue measures for rapid response to transport emergencies.[142] Statistics are gathered from accidents, then analyzed and used to determine safety measures to lower the casualty rate.[143]

Environment

[edit]

Transport is a major use of energy and burns most of the world's petroleum. This creates air pollution, including nitrous oxides and particulates, and is a significant contributor to global warming through emission of carbon dioxide,[145] for which transport is the fastest-growing emission sector.[146] According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the transportation sector accounts for more than one-third of CO2 emissions globally in the early 2020ies.[147] By sub-sector, road transport is the largest contributor to global warming.[148] Environmental regulations in developed countries have reduced individual vehicles' emissions; however, this has been offset by increases in the numbers of vehicles and in the use of each vehicle.[145] Some pathways to reduce the carbon emissions of road vehicles considerably have been studied.[149][150] Energy use and emissions vary largely between modes, causing environmentalists to call for a transition from air and road to rail and human-powered transport,[151] as well as increased transport electrification and energy efficiency.

Other environmental impacts of transport systems include traffic congestion and automobile-oriented urban sprawl, which can consume natural habitat and agricultural lands. By reducing transport emissions globally, it is predicted that there will be significant positive effects on Earth's air quality, acid rain, smog, and climate change.[152]

While electric cars are being built to cut down CO2 emission at the point of use, an approach that is becoming popular among cities worldwide is to prioritize public transport, bicycles, and pedestrian movement. Redirecting vehicle movement to create 20-minute neighbourhoods[153] that promotes exercise while greatly reducing vehicle dependency and pollution. Some policies are levying a congestion charge[154] to cars for travelling within congested areas during peak time.

Airplane emissions change depending on the flight distance. It takes a lot of energy to take off and land, so longer flights are more efficient per mile traveled. However, longer flights naturally use more fuel in total. Short flights produce the most CO2 per passenger mile, while long flights produce slightly less.[155][156] Things get worse when planes fly high in the atmosphere.[157][158] Their emissions trap much more heat than those released at ground level. This is not just because of CO2, but a mix of other greenhouse gases in the exhaust.[159][160] In 2022 global CO2 emissions from the transport sector grew by more than 250 Mt CO2 to nearly 8 Gt CO2, which represent more than 3% compared to 2021. Aviation was responsible for a significant part of that increase.[161]

City buses produce about 0.3 kg of CO2 for every mile traveled per passenger. For long-distance bus trips (over 20 miles), that pollution drops to about 0.08 kg of CO2 per passenger mile.[162][155] On average, commuter trains produce around 0.17 kg of CO2 for each mile traveled per passenger. Long-distance trains are slightly higher at about 0.19 kg of CO2 per passenger mile.[162][155][163] The fleet emission average for delivery vans, trucks and big rigs is 10.17 kg (22.4 lb) CO2 per gallon of diesel consumed. Delivery vans and trucks average about 7.8 mpg (or 1.3 kg of CO2 per mile) while big rigs average about 5.3 mpg (or 1.92 kg of CO2 per mile).[164][165]

Sustainable development

[edit]The United Nations first formally recognized the role of transport in sustainable development in the 1992 United Nations Earth summit. In the 2012 United Nations World Conference, global leaders unanimously recognized that transport and mobility are central to achieving the sustainability targets.[166] Since then, data has been collected to show that the transport sector contributes to a quarter of the global greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore sustainable transport has been mainstreamed across several of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, especially those related to food, security, health, energy, economic growth, infrastructure, and cities and human settlements. Meeting sustainable transport targets is said to be particularly important to achieving the Paris Agreement.[167]

There are various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that are promoting sustainable transport to meet the defined goals. These include SDG 3 on health (increased road safety), SDG 7 on energy, SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth, SDG 9 on resilient infrastructure, SDG 11 on sustainable cities (access to transport and expanded public transport), SDG 12 on sustainable consumption and production (ending fossil fuel subsidies), and SDG 14 on oceans, seas, and marine resources.[168]

Contemporary development studies recognise transportation networks as a key element of economic development, socio-economic well-being and poverty reduction.[169] However, road network development has not always fulfilled its original intentions and has contributed significantly to environmental degradation and, in some cases, led to the loss of cultural traditions and the marginalisation of indigenous peoples.[170][171] Compared to roads, the development of air links (helicopters and planes) has had an even more devastating impact. What is more, helicopters used for tourist activities are subject to considerable criticism from a perspective of environmental protection as well as sports ethics.[171]

History

[edit]

Natural

[edit]Humans' first ways to move included walking, running, and swimming. The domestication of animals introduced a new way to lay the burden of transport on more powerful creatures, allowing the hauling of heavier loads, or humans riding animals for greater speed and duration.[172] Inventions such as the wheel and the sled (U.K. sledge) helped make animal transport more efficient through the introduction of vehicles.[173]

The first forms of road transport involved animals, such as horses (domesticated in the 4th or the 3rd millennium BCE),[173] oxen (from about 8000 BCE),[174] or humans carrying goods over dirt tracks that often followed game trails.

Water transport

[edit]Water transport, including rowed and sailed vessels, dates back to time immemorial and was the only efficient way to transport large quantities or over large distances prior to the Industrial Revolution. The first watercraft were canoes either cut out from tree trunks or made of animal hides.[175] Early deep water transport was accomplished with ships that were either rowed or used the wind for propulsion, or a combination of the two.[176] The importance of water has led to most cities that grew up as sites for trading being located on rivers or on the sea-shore, often at the intersection of two bodies of water.

Mechanical

[edit]Until the Industrial Revolution, transport remained slow and costly, and production and consumption gravitated as close to each other as feasible.[citation needed] The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century saw several inventions fundamentally change transport. With the optical telegraph, communication became rapid and independent of the transport of physical objects.[177] The invention of the steam engine, closely followed by its application in rail transport, made land transport independent of human or animal muscles.[178] Both speed and capacity increased, allowing specialization through manufacturing being located independently of natural resources. The 19th century also saw the development of the steam ship, which sped up global transport.

With the development of the combustion engine and the automobile around 1900, road transport became more competitive again, and mechanical private transport originated. The first "modern" highways were constructed during the 19th century with macadam.[179][180] Later, tarmac and concrete became the dominant paving materials.

In 1903 the Wright brothers demonstrated the first successful controllable airplane, and after World War I (1914–1918) aircraft became a fast way to transport people and express goods over long distances.[181]

After World War II (1939–1945) the automobile and airlines took higher shares of transport, reducing rail and water to freight and short-haul passenger services.[182] Scientific spaceflight began in the 1950s, with rapid growth until the 1970s, when interest dwindled. In the 1950s the introduction of containerization gave massive efficiency gains in freight transport, fostering globalization.[124] International air travel became much more accessible in the 1960s with the commercialization of the jet engine. Along with the growth in automobiles and motorways, rail and water transport declined in relative importance. After the introduction of the Shinkansen in Japan in 1964, high-speed rail in Asia and Europe started attracting passengers on long-haul routes away from the airlines.[182]

In the U.S. during the 19th century, private joint-stock corporations owned most aqueducts, bridges, canals, railroads, roads, and tunnels.[183] Most such transport infrastructure came under government control in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the nationalization of inter-city passenger rail-service with the establishment of Amtrak.[184] However, as recently as 2010, a movement to privatize roads and other infrastructure has gained ground and adherents.[185]

See also

[edit]- Car-free movement

- Energy efficiency in transport

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Free public transport

- Green transport hierarchy

- Hazardous Materials Transportation Act

- Health and environmental impact of transport

- Health impact of light rail systems

- IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Society

- Journal of Transport and Land Use

- List of emerging transportation technologies

- Outline of transport

- Personal rapid transit

- Public transport accessibility level

- Rail transport by country

- Speed record

- Taxicabs by country

- Transport divide

References

[edit]- ^ Baudin, Michel; Netland, Torbjørn (2022). Introduction to Manufacturing: An Industrial Engineering and Management Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-11029-7.

- ^ Voortman, Craig (2004). Global Logistics Management. Juta and Company Ltd. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-0-7021-6641-9.

- ^ Rodrigue, Jean-Paul (2024). "Transport planning and policy". The Geography of Transport Systems (6th ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 272–295. doi:10.4324/9781003343196-9. ISBN 978-1-003-86032-7.

- ^ a b Kaminsky, Jessica A. (February 2018). "National Culture Shapes Private Investment in Transportation Infrastructure Projects around the Globe". Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 144 (2) 04017098. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001416.

- ^ Percoco, Marco (December 2014). "Quality of institutions and private participation in transport infrastructure investment: Evidence from developing countries". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 70. Elsevier: 50–58. Bibcode:2014TRPA...70...50P. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2014.10.004.

- ^ Wickham, J. (2006). "Public transport systems: The sinews of European urban citizenship?". European Societies. 8 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1080/14616690500491464.

- ^ Backx, Mattijs; et al. (July 2002). "Public, private and mixed ownership and the performance of international airlines". Journal of Air Transport Management. 8 (4): 213–220. doi:10.1016/S0969-6997(01)00053-9.

- ^ Belokurov, Vladimir; et al. (2018). "Modeling passenger transportation processes using vehicles of various forms of ownership". Transportation Research Procedia. 36: 44–49. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2018.12.041.

- ^ Kaukiainen, Yrjö (2014). "The role of shipping in the 'second stage of globalisation'". International Journal of Maritime History. 26 (1): 64–81. doi:10.1177/0843871413514505.

- ^ Mačiulis, A.; et al. (2009). "The impact of transport on the competitiveness of national economy". Transport. 24 (2): 93–99. doi:10.3846/1648-4142.2009.24.93-99.

- ^ Köhler, Jonathan (2013). "Globalization and Sustainable Development: Case Study on International Transport and Sustainable Development". The Journal of Environment & Development. 23 (1): 66–100. doi:10.1177/10704965135072 (inactive 17 October 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2025 (link) - ^ Small, Kenneth A. (May 1977). "Estimating the Air Pollution Costs of Transport Modes". Journal of Transport Economics and Policy. 11 (2): 109–132. JSTOR 20052465.

- ^ Lowe, Marcia D. (1993). "Cycling into the future". In Brown, Lester Russell (ed.). State of the World: A Worldwatch Institute Report on Progress Toward a Sustainable Society. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-393-30614-9.

- ^ a b Pendakur, V. Setty (2011). "Non-motorized urban transport as neglected modes". In Dimitriou, Harry T.; Gakenheimer, Ralph (eds.). Urban Transport in the Developing World: A Handbook of Policy and Practice. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 203–206. ISBN 978-1-84980-839-2.

- ^ Wilson, David Gordon (2004). Bicycling Science (Third ed.). MIT Press. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-262-73154-6.

- ^ Ho, Chaang-Iuan; et al. (2015). "Beyond environmental concerns: using means–end chains to explore the personal psychological values and motivations of leisure/recreational cyclists". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 23 (2): 234–254. Bibcode:2015JSusT..23..234H. doi:10.1080/09669582.2014.943762.

- ^ Munroe, Edward; Wong, Stephen (October 2025). "Shared-Use Paths: A Review of Design, Accessibility, and Sustainability". SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5551474. Retrieved 2025-10-13.

- ^ Brooks, Alec N.; et al. (December 1986). "Human-powered Watercraft". Scientific American. 255 (6): 120–131. Bibcode:1986SciAm.255f.120B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1286-120. JSTOR 24976108.

- ^ Formenti, Federico; et al. (August 7, 2005). "Human locomotion on snow: determinants of economy and speed of skiing across the ages". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1572): 1561–1569. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3121.

- ^ Drela, Mark; Langford, John S. (November 1985). "Human-powered Flight". Scientific American. 253 (5): 144–151. Bibcode:1985SciAm.253e.144D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1185-144. JSTOR 24967855.

- ^ Archibald, Mark (2011). Analysis of Light Alternative-Powered Vehicle Use and Potential in the United States. Proceedings of the ASME 2011 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. Transportation Systems; Safety Engineering, Risk Analysis and Reliability Methods; Applied Stochastic Optimization, Uncertainty and Probability. Denver, Colorado, USA. November 11–17. Vol. 9, art. IMECE2011-64714. ASME. pp. 319–326. doi:10.1115/IMECE2011-64714.

- ^ a b Baggerman, Jessica O. (2024). "Animal Power". In Webb, Jeffrey B.; Fee, Christopher R. (eds.). Energy in American History: A Political, Social, and Environmental Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 40–41. ISBN 979-8-216-17434-9.

- ^ Fennell, David A. (2011). Tourism and Animal Ethics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-57568-6.

- ^ Rathakrishnan, Ethirajan (2021). Introduction to Aerospace Engineering: Basic Principles of Flight. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-1-119-80715-5.

- ^ Crawford, Amy (October 25, 2021). "Could flying electric 'air taxis' help fix urban transportation?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- ^ Ashford, Norman J.; et al. (2011). Airport Engineering: Planning, Design, and Development of 21st Century Airports (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 74–104. ISBN 978-0-470-39855-5.

- ^ Talalay, P. G. (2024). "Construction of Snow and Ice Runways". Mining and Construction in Snow and Ice. Springer Polar Sciences. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-76508-7_3.

- ^ Morabito, Michael G. (August 19, 2021). "A Review of Hydrodynamic Design Methods for Seaplanes". Journal of Ship Production and Design. 37 (3): 159–180. doi:10.5957/JSPD.11180039.

- ^ Stickney, Wiley (May 9, 2025). "How Big Are Military Drones? (Sizes & Comparison)". boltflight.com. Retrieved 2025-10-14.

- ^ Fahlstrom, Paul G.; et al. (2022). Introduction to UAV Systems. Aerospace Series (5 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-119-80262-4.

- ^ Cooper & Shepherd 1998, p. 281.

- ^ "Swine flu prompts EU warning on travel to US". The Guardian. April 28, 2009. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- ^ Cooper, Iver P. (2025). Airships: Their Science, History and Future. McFarland. pp. 5–15. ISBN 978-1-4766-5413-3.

- ^ Ascher, Kate (2015). The Way to Go: Moving by Sea, Land, and Air. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-14-312794-9.

- ^ Timan, P. E. (2015). "Why Monorail Systems Provide a Great Solution for Metropolitan Areas". Urban Rail Transit. 1: 13–25. doi:10.1007/s40864-015-0001-1.

- ^ Yavuz, Mehmet Nedim; Öztürk, Zübeyde (2021). "Comparison of conventional high speed railway, maglev and hyperloop transportation systems". International Advanced Researches and Engineering Journal. 5 (1): 113–122. doi:10.35860/iarej.795779.

- ^ Sanchis, Ignacio Villalba; et al. (September 13, 2021). "Experimental and numerical investigations of dual gauge railway track behaviour". Construction and Building Materials. 299 123943. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123943.

- ^ Fang, Jun; et al. (November 2025). "Discrete element analysis of ballasted track mechanical behavior under rack vehicle loads on steep slopes". Transportation Geotechnics. 55 101659. Elsevier. Bibcode:2025TranG..5501659F. doi:10.1016/j.trgeo.2025.101659.

- ^ a b Spiryagin, Maksym; et al. (2014). Design and Simulation of Rail Vehicles. Ground vehicle engineering series. CRC Press. pp. 27–49. ISBN 978-1-4665-7566-0.

- ^ Duffy, M. C. (1998). "The Gas Turbine in Railway Traction". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 70 (1): 27–58. doi:10.1179/tns.1998.002.

- ^ Levin, Jonathan V. (2017). Where Have All the Horses Gone?: How Advancing Technology Swept American Horses from the Road, the Farm, the Range and the Battlefield. McFarland. pp. 75–80. ISBN 978-1-4766-6713-3.

- ^ Bellows, Alan (February 2008). "The Remarkable Pneumatic People-Mover". Damn Interesting. Retrieved 2025-10-14.

- ^ Smith, Clare (2023). Environmental Physics. Routledge Introductions to Environment: Environment and Society Texts. Taylor & Francis. pp. 74–78. ISBN 978-1-000-94501-0.

- ^ a b Cooper & Shepherd 1998, p. 279.

- ^ Nilson, Peter (June 5, 2023). "The 10 fastest high-speed trains in the world". Railway Technology. Verdict Network, GlobalData. Retrieved 2025-10-15.

- ^ Kim, Tschangho John, ed. (2009). Transportation Engineering and Planning. Vol. I. EOLSS Publications. pp. 191–197. ISBN 978-1-905839-80-3.

- ^ Barry, Steve (2008). Railroad Rolling Stock. Voyageur Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-61673-209-7.

- ^ Barkan, Christopher P. L.; et al. (May 2007). "Optimizing the design of railway tank cars to minimize accident-caused releases". Computers & Operations Research. 34 (5). Elsevier: 1266–1286. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2005.06.002.

- ^ "Major Roads of the United States". United States Department of the Interior. 2006-03-13. Archived from the original on 13 April 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "Road Infrastructure Strategic Framework for South Africa". National Department of Transport (South Africa). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ Lay 1992, pp. 6–7.

- ^ "What is the difference between a road and a street?". Word FAQ. Lexico Publishing Group. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 April 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "Vehicle Miles Traveled by Highway Category and Vehicle Type". Home, United States Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2025-10-15.

- ^ Jess, Andreas; Wasserscheid, Peter (2020). Chemical Technology: From Principles to Products (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-34421-5.

- ^ a b c Rodrigue, Jean-Paul; et al. (2013). The Geography of Transport Systems (3 ed.). Routledge. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-136-77732-5.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (March 5, 2020). "One in five Europeans exposed to harmful noise pollution – study". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ^ "The Science of Buoyancy and Hull Design" (PDF). Torpedo Bay Navy Museum. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Kander, Astrid; et al. (2015). Power to the People: Energy in Europe over the Last Five Centuries. The Princeton Economic History of the Western World. Princeton University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-691-16822-7.

- ^ Karanassos, Harry (2015). Commercial Ship Surveying: On/Off Hire Condition Surveys and Bunker Surveys. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-08-100304-6.

- ^ "Nuclear Submarines and Aircraft Carriers". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 2025-10-15.

- ^ Gordon, Jamie (2023). PCOC Boating Safety Course Manual. Sail Canada. ISBN 978-1-990076-18-3.

- ^ Lavis, David (February 1985). "Air Cushion Craft". Naval Engineers Journal. 97 (2): 259–316. Bibcode:1985NEngJ..97..259L. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1985.tb03401.x.

- ^ Review of Maritime Transport (PDF). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). New York and Geneva: United Nations. 2007. pp. x, 32. ISBN 978-92-1-112725-6. Retrieved 2025-10-12.

- ^ Stopford 1997, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Stopford 1997, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Cooper & Shepherd 1998, p. 280.

- ^ Noll, Gregory G.; Hildebrand, Michael S. (2022). Hazardous Materials: Managing the Incident with Navigate Advantage Access. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-284-25567-6.

- ^ Garde, R. J.; Raju, K. G. Ranga (2000). Mechanics of Sediment Transportation and Alluvial Stream Problems. New age reference. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-81-224-1270-3.

- ^ Belova, O. V.; Vulf, M. D. (2016). "Pneumatic Capsule Transport". Procedia Engineering. 152. Elsevier: 276–280. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.07.703.

- ^ Lucas, Jarrod; Tap, Katrina (June 11, 2025). "WA Government to increase capacity of historic Goldfields water pipeline by 2027". ABC News. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Siala, T. F.; Stoner, J. R. "The Great Man-Made River Project". In Atalah, Alan; Tremblay, Armand (eds.). Pipelines 2006: Service to the Owner. Pipeline Division Specialty Conference, held in Chicago, Illinois, July 30-August 2, 2006. pp. 1–8. doi:10.1061/40854(211)32. ISBN 978-0-7844-0854-4.

- ^ Blackman, Sarah (October 17, 2012). "The world's longest oil and gas pipelines". Offshore Technology. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ a b Neumann, Edward S. (January 19, 2010). "The past, present, and future of urban cable propelled people movers". Journal of Advanced Transportation. 33 (1): 51–82. doi:10.1002/atr.5670330106.

- ^ Alshalalfah, B.; et al. (2012). "Aerial Ropeway Transportation Systems in the Urban Environment: State of the Art". Journal of Transportation Engineering. 138 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)TE.1943-5436.0000330.

- ^ Warnes, Kathy (2014). "Funicular Railways". In Garrett, Mark (ed.). Encyclopedia of Transportation: Social Science and Policy. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4833-8980-6.

- ^ Neumann, Edward S.; et al. (November 1985). "Modern Material Ropeway Capabilities and Characteristics". Journal of Transportation Engineering. 111 (6): 651–663. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-947X(1985)111:6(651).

- ^ Quizona, K. D.; et al. (2018). "Physical and digital architecture for collection and analysis of imparted accelerations on Zip Line attractions". Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies. 1 (1): 61–65. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Hiriart, Thomas; Saleh, Joseph H. (February 2010). "Observations on the evolution of satellite launch volume and cyclicality in the space industry". Space Policy. 26 (1). Elsevier: 53–60. Bibcode:2010SpPol..26...53H. doi:10.1016/j.spacepol.2009.11.001.

- ^ "Lunar Mission Summaries". Lunar and Planetary Institute. 2025. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "International Space Station Expeditions". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2025. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "A Planetary Society Retrospective". The Planetary Society. September 21, 2020. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ George, Shaji; et al. (2024). "Rocket-Powered E-Commerce: Exploring the Feasibility and Implications of Suborbital Package Delivery". Partners Universal Innovative Research Publication. 2 (2). doi:10.5281/zenodo.10951330.

- ^ Callsen, Steffen; et al. (November 2023). "Feasible options for point-to-point passenger transport with rocket propelled reusable launch vehicles". Acta Astronautica. 212. Elsevier: 100–110. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2023.07.016.

- ^ Verma, Alok (2021). Development Policy and Administration. K. K. Publications.

- ^ a b Pollalis, Spiro N. (2016). Planning Sustainable Cities: An infrastructure-based approach. Routledge. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1-317-28276-1.

- ^ Cooper & Shepherd 1998, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Vis, Iris F. A.; de Koster, René (May 16, 2003). "Transshipment of containers at a container terminal: An overview". European Journal of Operational Research. 147 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00293-X.

- ^ de Palma, André; Monardo, Julien (2021). "Natural Monopoly in Transport". International Encyclopedia of Transportation. 2. Elsevier. pp. 30–35. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102671-7.10006-5. ISBN 978-0-08-102672-4. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Odeck, James (April 2017). "Government versus toll funding of road projects – A theoretical consideration with an ex-post evaluation of implemented toll projects". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 98: 97–107. Bibcode:2017TRPA...98...97O. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2017.01.007.

- ^ Santos, Georgina; et al. (2010). "Part I: Externalities and economic policies in road transport". Research in Transportation Economics. 28 (1): 2–45. doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2009.11.002.

- ^ Flyvbjerg, Bent; et al. (June 30, 2005). "How (In)accurate Are Demand Forecasts in Public Works Projects?: The Case of Transportation". Journal of the American Planning Association. 71 (2): 131–146. arXiv:1303.6654. doi:10.1080/01944360508976688. ISSN 0194-4363.

- ^ Alves, Rômulo Romeu Nóbrega (2018). "The Ethnozoological Role of Working Animals in Traction and Transport". Ethnozoology: Animals in Our Lives. pp. 339–349. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809913-1.00018-1.

- ^ Norris, Zeeshan (2019). Tourism Concepts and Principles. Ed-Tech Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-1-83947-439-2.

- ^ Loeb, Alan P. (2004). "Steam Versus Electric Versus Internal Combustion: Choosing Vehicle Technology at the Start of the Automotive Age". Transportation Research Record. 1885 (1): 1–7. doi:10.3141/1885-01.

- ^ Meisl, Claus (July 1992). Rocket engine versus jet engine comparison. 28th Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit. p. 3686. doi:10.2514/6.1992-3686.

- ^ Wasbari, F.; et al. (January 2017). "A review of compressed-air hybrid technology in vehicle system". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 67: 935–953. Bibcode:2017RSERv..67..935W. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.039.

- ^ Yong, R. N.; et al. (2012). Vehicle Traction Mechanics. Developments in Agricultural Engineering. Vol. 3. Elsevier. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-444-60048-6.

- ^ Sproule, W. J., ed. (June 25, 2020). Automated People Movers and Automated Transit Systems 2020: Automated Transit for Smart Mobility. 17th International Conference on Automated People Movers and Automated Transit Systems. American Society of Civil Engineers. doi:10.1061/9780784483077.

- ^ Monye, Stella Isioma; et al. (2023). Impact of Industry (4.O) in Automobile Industry. 15th International Conference on Materials Processing and Characterization (ICMPC 2023). E3S Web of Conferences. Vol. 430, art. 01222. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202343001222.

- ^ Ross, P.; Maynard, K. (2021). "Towards a 4th industrial revolution". Intelligent Buildings International. 13 (3): 159–161. doi:10.1080/17508975.2021.1873625.

- ^ Hamid, Umar Zakir Abdul; et al. (2021). "Facilitating a Reliable, Feasible, and Comfortable Future Mobility". SAE International Journal of Connected and Automated Vehicles. 4 (1). Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Mizutani, F. (2006). "The role of private provision in transport markets: effects of private ownership and business diversification". Structural Change in Transportation and Communications in the Knowledge Society. Edward Elgar. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-1-78254-203-2.

- ^ Nash, Chris (2005). "Privatization in Transport Available to Purchase". In Button, Kenneth J.; Hensher, David A. (eds.). Handbook of Transport Strategy, Policy and Institutions. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi:10.1108/9780080456041-007. ISBN 978-0-08045-604-1.

- ^ Stopford 1997, p. 422.

- ^ Stopford 1997, p. 29.

- ^ Meredith, Sam (2018-05-17). "Two-thirds of global population will live in cities by 2050, UN says". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ Jones, Peter (July 2014). "The evolution of urban mobility: The interplay of academic and policy perspectives". IATSS Research. 38: 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.iatssr.2014.06.001.

- ^ Morozov, Viacheslav; et al. (2024). "Ideology of Urban Road Transport Chaos and Accident Risk Management for Sustainable Transport Systems". Sustainability. 16 (6) 2596. Bibcode:2024Sust...16.2596M. doi:10.3390/su16062596.

- ^ Hoogma, Remco; et al. (2005). "Promises for Sustainable Transport". Experimenting for Sustainable Transport: The Approach of Strategic Niche Management. Transport, Development and Sustainability Series. Routledge. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-1-134-48822-3.

- ^ OECD (2010). "The Future for Interurban Passenger Transport Bringing Citizens Closer Together: Bringing Citizens Closer Together". International symposium on transport economics and policy. 2010-2011 of OECD/ITF Joint Transport Research Centre Discussion Papers. Vol. 18. OECD Publishing. p. 434. ISBN 978-92-821-0268-8.

- ^ Dacko, Scott G.; Spalteholz, Carolin (November 2014). "Upgrading the city: Enabling intermodal travel behaviour". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 89. Elsevier: 222–235. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2013.08.039.

- ^ Pitsiava-Latinopoulou, Magda; Iordanopoulos, Panagiotis (2012). "Intermodal Passengers Terminals: Design Standards for Better Level of Service". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 48. Elsevier: 3297–3306. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.1295.

- ^ Butler, Peter (November 21, 2022). "Planes, Trains, Cars and Buses: We Do the Math to Find the Cheapest Way to Travel Per Mile". CNET. Retrieved 2025-10-18.

- ^ Neumayer, Eric (March 2006). "Unequal access to foreign spaces: how states use visa restrictions to regulate mobility in a globalized world". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 31 (1): 72–84. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2006.00194.

- ^ Skinner, Henry Alan (1949). The Origin of Medical Terms. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 21.

- ^ Branas, C. C.; MacKenzie, E. J.; Williams, J. C.; Schwab, C. W.; Teter, H. M.; Flanigan, M. C.; et al. (2005). "Access to trauma centers in the United States". JAMA. 293 (21): 2626–2633. doi:10.1001/jama.293.21.2626. PMID 15928284.

- ^ Burney, R. E.; Hubert, D.; Passini, L.; Maio, R. (1995). "Variation in air medical outcomes by crew composition: a two-year follow-up". Ann Emerg Med. 25 (2): 187–192. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70322-5. PMID 7832345.

- ^ Chopra & Meindl 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Chopra & Meindl 2007, pp. 63–64.

- ^ McLeod, Sam; Curtis, Carey (2020-03-14). "Understanding and Planning for Freight Movement in Cities: Practices and Challenges". Planning Practice & Research. 35 (2): 201–219. doi:10.1080/02697459.2020.1732660. ISSN 0269-7459. S2CID 214463529.

- ^ Chopra & Meindl 2007, p. 54.

- ^ Bardi, Coyle & Novack 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Bardi, Coyle & Novack 2006, p. 473.

- ^ a b Bardi, Coyle & Novack 2006, pp. 211–214.

- ^ Trace, Keith (2008). "Bulk Commodity Logistics". In Brewer, Ann M.; et al. (eds.). Handbook of Logistics and Supply-Chain Management. Handbook in Transport. Vol. 2. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi:10.1108/9780080435930-029.

- ^ Chopra & Meindl 2007, p. 328.

- ^ Ahmed, Sirwan K.; et al. (May 2023). "Road traffic accidental injuries and deaths: A neglected global health issue". Health Science Reports. 6 (5) e1240. doi:10.1002/hsr2.1240. PMC 10154805. PMID 37152220.

- ^ Petrescu, Relly Victoria; et al. (2017). "Transportation Engineering". American Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences. 10 (3): 685–702. doi:10.3844/ajeassp.2017.685.702. Retrieved 2025-10-15.

- ^ Stopford 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Davies, Andrea Rees; Frink, Brenda D. (2014). "The Origins of the Ideal Worker: The Separation of Work and Home in the United States From the Market Revolution to 1950". Work and Occupations. 41 (1): 18–39. doi:10.1177/0730888413515893.

- ^ "The Seven Wastes of Lean Manufacturing". EKU Online. Eastern Kentucky University. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ Spear, B. D. (1996). "New approaches to transportation forecasting models". Transportation. 23 (3): 215–240. doi:10.1007/BF00165703.

- ^ Turbaningsih, O. (2022). "The study of project cargo logistics operation: a general overview". Journal of Shipping and Trade 7. 7 24. doi:10.1186/s41072-022-00125-6.

- ^ Gopi, Satheesh (2009). Basic Civil Engineering. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131792889.

- ^ Khisty, C. J.; Ayvalik, C. K. (2003). "Automobile Dominance and the Tragedy of the Land-Use/Transport System: Some Critical Issues". Systemic Practice and Action Research. 16: 53–73. doi:10.1023/A:1021932712598.

- ^ Chatman, D. G.; Noland, R. B. (2011). "Do Public Transport Improvements Increase Agglomeration Economies? A Review of Literature and an Agenda for Research". Transport Reviews. 31 (6): 725–742. doi:10.1080/01441647.2011.587908.

- ^ Feagin, Joe R.; Parker, Robert (2002). Building American Cities: The Urban Real Estate Game. Beard Books. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-58798-148-7.

- ^ O'Shea, Rose Ann (2005). Principles and Practice of Trauma Nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-443-06405-0.

- ^ Lave, Lester B. (Summer 1968). "Safety in Transportation: The Role of Government". Law and Contemporary Problems. 33 (3). Duke University School of Law: 512–535. doi:10.2307/1190940. JSTOR 1190940.

- ^ Baxter, Terry (June 1995). "Independent investigation of transportation accidents". Safety Science. 19 (2–3): 271–278. doi:10.1016/0925-7535(94)00029-3.

- ^ Sapuan, S. M.; et al. (2022). "Safety Issues in Transportation Design". Safety and Health in Composite Industry. Composites Science and Technology. Singapore: Springer. pp. 267–291. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-6136-5_13. ISBN 978-981-16-6135-8.

- ^ Matveev, Aleksandr; et al. (2018). "Methods improving the availability of emergency-rescue services for emergency response to transport accidents". Transportation Research Procedia. 36: 507–513. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2018.12.137.

- ^ Evans, Andrew W. (July 2003). "Estimating transport fatality risk from past accident data". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 35 (4): 459–472. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00024-6. PMID 12729810.

- ^ "A world of thoughts on Phase 2". International Council on Clean Transportation. September 16, 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ^ a b Fuglestvet; et al. (2007). "Climate forcing from the transport sectors" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (2). Center for International Climate and Environmental Research: 454–458. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105..454F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702958104. PMC 2206557. PMID 18180450. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ Worldwatch Institute (16 January 2008). "Analysis: Nano Hypocrisy?". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ "WIPO Technology Trends: Future of Transportation - 2 Overview of transportation and its megatrends". WIPO Technology Trends.

- ^ Jan Fuglestvedt; et al. (Jan 15, 2008). "Climate forcing from the transport sectors" (PDF). PNAS. 105 (2): 454–458. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105..454F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702958104. PMC 2206557. PMID 18180450. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ "Claverton-Energy.com". Claverton-Energy.com. 2009-02-17. Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Data on the barriers and motivators to more sustainable transport behaviour is available in the UK Department for Transport study: "Climate Change and Transport Choices". December 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-05-30. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- ^ Cuenot, Francois; et al. (February 2012). "The prospect for modal shifts in passenger transport worldwide and impacts on energy use and CO2". Energy Policy. 41. Elsevier: 98–106. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.07.017.

- ^ Environment Canada. "Transportation". Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ^ Planning (September 9, 2020). "20-minute neighbourhoods". Planning. Archived from the original on 2021-09-20. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Congestion Charge (Official)". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ a b c "How We Calculate Your Carbon Footprint". Archived from the original on 2012-01-03. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ^ "[SafeClimate] measuring and reporting | tools". Archived from the original on 2008-03-27. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ I, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Working Group (1995-05-04). Climate Change 1994: Radiative Forcing of Climate Change and an Evaluation of the IPCC 1992 IS92 Emission Scenarios. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55962-1.

- ^ Dempsey, Paul Stephen; Jakhu, Ram S. (2016-07-15). Routledge Handbook of Public Aviation Law. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-29775-0.

- ^ Schumann, Ulrich (2011). "American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Potential to reduce the climate impact of aviation by flight level changes" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ^ Lee, D. S.; Pitari, G.; Grewe, V.; Gierens, K.; Penner, J. E.; Petzold, A.; Prather, M. J.; Schumann, U.; Bais, A.; Berntsen, T.; Iachetti, D.; Lim, L. L.; Sausen, R. (2010), "Transport impacts on atmosphere and climate: Aviation" (PDF), Atmospheric Environment Transport Impacts on Atmosphere and Climate: The ATTICA Assessment Report, vol. 44, pp. 4678–4734, retrieved 2025-10-12

- ^ "Transport - Energy System". IEA. Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ a b "CO2 Emissions from Employee Commuting in Non-company Owned Vehicles". World Resources Institute. Archived from the original on 2016-01-12. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ^ "'Dramatically more powerful': world's first battery-electric freight train unveiled". the Guardian. 2021-09-16. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Kodjak, Drew (August 29, 2004). Policy Discussion – Heavy-Duty Truck Fuel Economy (PDF). 10th Diesel Engine Emissions Reduction (DEER) Conference. Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Coronado, California. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ^ Endresen, Øyvind; Sørgård, Eirik; Sundet, Jostein K.; Dalsøren, Stig B.; Isaksen, Ivar S. A.; Berglen, Tore F.; Gravir, Gjermund (2003-09-16). "Emission from international sea transportation and environmental impact". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 108 (D17): 4560. Bibcode:2003JGRD..108.4560E. doi:10.1029/2002JD002898. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ^ "Sustainable transport". United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved 2025-10-19.

- ^ "Sustainable transport". Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Archived from the original on 2020-10-09. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Sustainable transport at the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)". Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Archived from the original on 2020-10-15. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Beazley, R.; Lassoie, J. (2017). Himalayan Mobilities: an Exploration of The Impact of Expanding Rural Road Networks on Social and Ecological Systems in The Nepalese Himalaya. SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55757-1. ISBN 978-3-319-55755-7.

- ^ Beazley, R. (2013). Impacts of Expanding Rural Road Networks on Communities in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal (PDF) (M.S. thesis). Cornell University. Retrieved 2025-10-12.

- ^ a b Apollo, Michal (2024-08-27). "A bridge too far: The dilemma of transport development in peripheral mountain areas". Journal of Tourism Futures. 11: 23–37. doi:10.1108/JTF-04-2024-0065. ISSN 2055-5911.

- ^ Weissenbacher, Manfred (2009). Sources of Power: How Energy Forges Human History. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 57–75. ISBN 978-0-313-35627-8.

- ^ a b Rossi, C.; et al. (2016). "Ancient road transport devices: Developments from the Bronze Age to the Roman Empire". Frontiers of Mechanical Engineering. 11: 12–25. doi:10.1007/s11465-015-0358-6.

- ^ Watts, Martin (1999). Working Oxen. Shire Album. Vol. 342. Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire: Osprey Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7478-0415-4. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

[...] tamed aurochs became the first domestic oxen. The earliest evidence for domestication is found in the Middle East around ten thousand years ago.

- ^ Gjerde, Jan Magne (May 2021). "The earliest boat depictions in Northern Europe: newly discovered early Mesolithic rock art at Valle, northern Norway". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 40 (2). Wiley: 136–152. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12214.

- ^ McGrail, Sean (2004). Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times. ACLS Humanities E-Book. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–70. ISBN 978-0-19-927186-3.

- ^ Fairclough, Mary (2013). "The Telegraph: Radical Transmission in the 1790s". Eighteenth-Century Life. 37 (2): 26–52. doi:10.1215/00982601-2080973.

- ^ Kitsikopoulos, H. (2023). "Steam Power in Transportation: Railways". An Economic History of British Steam Engines, 1774-1870. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-27362-9_8.

- ^ Merdinger, Charles J. (July–August 1952). "Roads — through the Ages: I. Early Developments". The Military Engineer. 44 (300): 268–273. JSTOR 44569675.

- ^ Clow, Don (2004). "From Macadam to Asphalt: The Paving of the Streets of London in the Victorian Era. Part 1 — From Macadam To Stone Sett". Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society. Retrieved 2025-10-19.

- ^ Bardi, Coyle & Novack 2006, p. 158.

- ^ a b Cooper & Shepherd 1998, p. 277.

- ^ Wright, Robert E. (March 26, 2024). "Private Ownership of Canals, Railways, Bridges, and Other Transportation Infrastructure". SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4773901. Retrieved 2025-10-19.

- ^ Francaviglia, Richard V. (1972). "Amtrak: decisions and dilemmas of American rail passenger service in 1971". The Professional Geographer. 24 (3): 242–245. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.1972.00242.x.

- ^ Winston, Clifford (2010). Last exit: privatization and deregulation of the U.S. transportation system. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-0473-7. OCLC 635492422.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bardi, Edward; Coyle, John & Novack, Robert (2006). Management of Transportation. Australia: Thomson South-Western. ISBN 0-324-31443-4. OCLC 62259402.

- Chopra, Sunil & Meindl, Peter (2007). Supply chain management: strategy, planning, and operation (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-208608-0. OCLC 63808135.

- Cooper, Christopher P.; Shepherd, Rebecca (1998). Tourism: Principles and Practice (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Financial Times Prent. Int. ISBN 978-0-582-31273-9. OCLC 39945061. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- Lay, Maxwell G (1992). Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles that Used Them. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2691-4. OCLC 804297312.

- Stopford, Martin (1997). Maritime Economics (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15310-7. OCLC 36824728.

Further reading

[edit]- McKibben, Bill, "Toward a Land of Buses and Bikes" (review of Ben Goldfarb, Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, Norton, 2023, 370 pp.; and Henry Grabar, Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World, Penguin Press, 2023, 346 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no. 15 (5 October 2023), pp. 30–32. "Someday in the not impossibly distant future, if we manage to prevent a global warming catastrophe, you could imagine a post-auto world where bikes and buses and trains are ever more important, as seems to be happening in Europe at the moment." (p. 32.)

External links

[edit]- Transportation from UCB Libraries GovPubs

Transport

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Transportation is the intentional movement of people, goods, animals, or information from one location to another, serving as a derived economic demand that spatially links supply with demand to facilitate exchange and specialization.[10] Unlike production or consumption, transport itself generates no intrinsic value but enables causal chains of economic activity by overcoming spatial separation, where the friction of distance—manifested in time, monetary costs, and effort—imposes barriers to mobility that must be mitigated for efficient flows.[10] This process requires infrastructure networks of nodes (e.g., ports, stations) and links (e.g., roads, rails), vehicles or carriers, and coordination to trace movements from origin to destination across modes.[11] Core principles governing transportation systems emphasize systemic integration and efficiency. First, all components—carried entities, vehicles, and networks—must be analyzed holistically, accounting for complete trip chains rather than isolated segments, as partial views ignore interdependencies like modal shifts or backhauls.[11] Second, distance remains relative, shaped not only by Euclidean measures but by accessibility factors such as topography, congestion, and technology, where advancements like containerization have compressed effective space-time through higher velocities and scale.[10] Third, space simultaneously generates mobility needs (e.g., urban density spurs commuting), supports it via infrastructure (e.g., pipelines for bulk fluids), and constrains it (e.g., land scarcity limits expansion), often demanding trade-offs like land consumption, which can reach 50% of urban areas in car-dependent cities.[10] Transportation operates as a market equilibrating supply (capacity and service levels) with demand (volumes and preferences), influenced by variables like speed, reliability, and cost, while broader objectives—such as safety or environmental impacts—require evaluating demand management options alongside supply expansions.[11] Massification through economies of scale (e.g., hub-and-spoke networks) enhances efficiency but contends with atomization, where individualized demands fragment flows, necessitating managerial innovations like just-in-time logistics to align velocity across modes.[10] These principles underscore transport's role not as an end but as a means to higher-order goals, with analyses extending to indirect effects like induced traffic from new infrastructure.[11]Economic Role and Necessity