Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Post-classical history

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

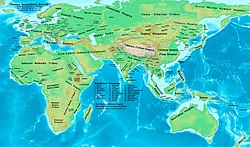

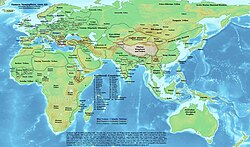

In world history, post-classical history refers to the period from about 500 CE to about 1450 or 1500 CE, roughly corresponding to the European Middle Ages following the decline of the western Roman Empire. The post-classical period is characterized by the expansion of certain civilizations geographically, by ongoing wars fought over land, resources and religion, and by the development of trade networks between often-distant civilizations.[1][2][3][A] This period is also called—with various implications and emphases—the medieval era, the post-antiquity era, the post-ancient era, or the pre-modern era.

In Asia and the Middle East during this time, the spread of Islam helped produce a series of caliphates which fostered the Islamic Golden Age, leading to advances in science and greater trade between those in the Asian, African, and European continents. East Asia experienced the entrenchment of the power of a unitary and Imperial China, the dynastic governance and culture of which influenced Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Religions such as Buddhism and neo-Confucianism spread in the region,[5] while Christianity became entrenched in Europe and increasingly elsewhere. Gunpowder was developed in China during the post-classical era. The Mongol Empire conquered and controlled much of Europe and Asia, permitting more trade and cultural and intellectual exchange between the two regions.[6]

In total, the population of the world broadly doubled in this period of history: from approximately 210 million in 500 CE to some 461 million in 1500 CE.[7] The population generally grew slowly throughout the period, with mortality generally high and rapid major declines due to events including the Plague of Justinian, the Mongol invasions, and the Black Death.[8]

Historiography

[edit]Terminology and periodization

[edit]

Post-classical history is a periodization used by historians employing a world history approach to history, specifically the school developed during the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[3] Outside of world history, the term is also sometimes used to avoid erroneous pre-conceptions around the terms Middle Ages, Medieval Period, and the Dark Ages (see medievalism), though the application of the term post-classical on a global scale is also problematic, and may likewise be Eurocentric.[9] Academic publications sometimes use the terms post-classical and late antiquity synonymously to describe the history of Western Eurasia between 250 and 800 CE.[10][11]

The post-classical period corresponds roughly to the period from 500 CE to 1450 CE.[1][12][3] Beginning and ending dates might vary depending on the region, with the period beginning at the end of the previous classical period: Han China (ending in 220 CE), the Western Roman Empire (in 476 CE), the Gupta Empire (in 543 CE), and the Sasanian Empire (in 651 CE).[13]

The post-classical period is one of the five or six major periods world historians use:

- early civilization,

- classical societies,

- post-classical

- early modern,

- long nineteenth century, and

- contemporary or modern era.[3] (Sometimes the nineteenth century and modern are combined.[3])

Although post-classical is synonymous with the Middle Ages of Western Europe, the term post-classical is not necessarily a member of the traditional tripartite periodization of Western European history into classical, middle, and modern.

Approaches

[edit]

The historical field of world history, which looks at common themes occurring across multiple cultures and regions, has enjoyed extensive development since the 1980s.[14] However, World History research has tended to focus on early modern globalization (beginning around 1500) and subsequent developments, and views post-classical history as mainly pertaining to Afro-Eurasia.[3] Historians recognize the difficulties of creating a periodization and identifying common themes that include not only this region but also, for example, the Americas, since they had little contact with Afro-Eurasia before the Columbian exchange.[3] Thus researchers around the year 2020 emphasized that "a global history of the period between 500 and 1500 is still wanting" and that "historians have only just begun to embark on a global history of the Middle Ages".[15][16]

For many regions of the world, there are well established histories. Although medieval studies in Europe tended in the 19th century to focus on creating histories for individual nation-states, much 20th-century research focused, successfully, on creating an integrated history of medieval Europe.[17][18][19][15] The Islamic World likewise has a rich regional historiography, ranging from the 14th-century Ibn Khaldun to the 20th-century Marshall Hodgson and beyond.[20] Correspondingly, research into the network of commercial hubs which enabled goods and ideas to move between China in the East and the Atlantic islands in the West—which can be called the early history of globalization—is fairly advanced; one key historian in this field is Janet Abu-Lughod.[15] Understanding of communication within sub-Saharan Africa or the Americas is, by contrast, far more limited.[15]

Around the 2010s, therefore, researchers began to explore the possibilities of writing history covering the Old World, where human activities were fairly interconnected, and establish its relationship with other cultural spheres, such as the Americas and Oceania. In the assessment of James Belich, John Darwin, Margret Frenz, and Chris Wickham,

Global history may be boundless, but global historians are not. Global history cannot usefully mean the history of everything, everywhere, all the time. [...] Three approaches [...] seem to us to have real promise. One is global history as the pursuit of significant historical problems across time, space, and specialism. This can sometimes be characterized as 'comparative' history. [...] Another is connectedness, including transnational relationships. [...] The third approach is the study of globalization [...]. Globalization is a term that needs to be rescued from the present, and salvaged for the past. To define it as always encompassing the whole planet is to mistake the current outcome for a very ancient process.[21]

A number of commentators have pointed to the history of the Earth's climate as a useful approach to World History in the Middle Ages, noting that certain climate events had effects on all human populations.[22][23][24][25][26][27]

Global trends

[edit]The post-classical era saw several common developments or themes. There was the expansion and growth of civilization into new geographic areas; the rise and/or spread of the three major world, or missionary, religions; and a period of rapidly expanding trade and trade networks. While scholastic emphasis has remained on Eurasia there is a growing effort to examine the effects of these global trends on other places.[1] In describing geographic zones historians have identified three large self contained world regions, Afro-Eurasia, the Americas, and Oceania.[9][B]

Growth of civilization

[edit]

First was the expansion and growth of civilization into new geographic areas across Asia, Africa, Europe, Mesoamerica, and western South America. However, as noted by world historian Peter N. Stearns, there were no common global political trends during the post-classical period, rather it was a period of loosely organized states and other developments, but no common political patterns emerged.[3] In Asia, China continued its historic dynastic cycle and became more complex, improving its bureaucracy. The creation of the Islamic empires established a new power in the Middle East, North Africa, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. The Mali and Songhai Empires were formed in West Africa. The fall of Roman civilization not only left a power vacuum for the Mediterranean and Europe, but forced certain areas to build what some historians might call new civilizations entirely.[29] An entirely different political system was applied in Western Europe (i.e. feudalism), as well as a different society (i.e. manorialism). However, the once Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) retained many features of old Rome, as well as Greek and Persian similarities. Kievan Rus' and subsequently Russia began development in Eastern Europe as well. In the isolated Americas, the Mississippian culture spread in North America and Mesoamerica saw the building of the Aztec Empire, while the Andean region of South America saw the establishment of the Wari Empire first and the Inca Empire later.[30] In Oceania, ancestors of modern Polynesians were established in village communities by the 6th century, a gradual intensification of complexity took place. In the 13th century, complex states were established, most notably the Tuʻi Tonga Empire which collected tribute from many island chains in the greater region.[31]

Spread of universal religions

[edit]

Religion that envisaged the possibility that all humans could be included in a universal order had emerged already in the first millennium BCE, particularly with Buddhism. In the following millennium, Buddhism was joined by two other major, universalizing, missionary religions, both developing from Judaism: Christianity and Islam. By the end of the period, these three religions were between them widespread, and often politically dominant, across the Old World.[32]

- Buddhism spread from India into China and flourished there briefly before using it as a hub to spread to Japan, Korea, and Vietnam;[33] a similar effect occurred with Confucian revivalism in the later centuries.[32]

- Christianity had become the state church of the Roman Empire in 380, and continued spreading into northern and eastern Europe during the post-classical period at the expense of belief systems that Christians labelled pagan.[34] An attempt was even made to incur upon the Middle East during the Crusades. The split of the Catholic Church in Western Europe and the Eastern Orthodox Church in Eastern Europe encouraged religious and cultural diversity in Eurasia.[35]

- Islam began between 610 and 632, with a series of revelations to Muhammad. It helped unify the warring Bedouin clans of the Arabian Peninsula and, through a rapid series of Muslim conquests, became established to the west across North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and parts of West Africa, and to the east across Persia, Central Asia, India, and Indonesia.[36]

Outside of Eurasia, religion or otherwise a veneration of the supernatural was also used to reinforce power structures, articulate world views and create foundational myths for society. Mesoamerican cosmological narratives are an example of this.[9]

Trade and communication

[edit]

Finally, communication and trade across Afro-Eurasia increased rapidly. The Silk Road continued to spread cultures and ideas through trade. Communication spread throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa. Trade networks were established between western Europe, Byzantium, early Russia, the Islamic Empires, and the Far Eastern civilizations.[37] In Africa, the earlier introduction of the camel allowed for a new and eventually large trans-Saharan trade, which connected Sub-Saharan West Africa to Eurasia. The Islamic Empires adopted many Greek, Roman, and Indian advances and spread them through the Islamic sphere of influence, allowing these developments to reach Europe, North and West Africa, and Central Asia. Islamic sea trade helped connect these areas, including those in the Indian Ocean and in the Mediterranean, replacing Byzantium in the latter region. The Christian Crusades into the Middle East (as well as Muslim Spain and Sicily) brought Islamic science, technology, and goods to Western Europe.[34] Western trade into East Asia was pioneered by Marco Polo. Importantly, China began to influence regions like Japan,[33] Korea, and Vietnam through trade and conquest. Finally, the growth of the Mongol Empire in Central Asia established safe trade which allowed goods, cultures, ideas, and disease to spread between Asia, Europe, and Africa.

The Americas had their own trade network, but here trade was restricted by range and scope. The Mayan network spread across Mesoamerica but lacked direct connections to the complex societies of South and North America, and these zones remained separate from one another.[38]

In Oceania, some of the island chains of Polynesia engaged in trade with one another.[39] For instance, with outrigger canoes long-distance communication of over 2,300 miles between Hawaii and Tahiti was maintained for centuries before its disruption and separation.[40] Meanwhile, in Melanesia there is evidence of exchanges between mainland Papua New Guinea and the Trobriand Islands off its coast, most likely for obsidian. Populations moved westward until 1200, after which the network dissolved into much smaller economies.[41]

Climate

[edit]During post-classical times, there is evidence that many regions of the world were affected similarly by global climate conditions; however, direct effects in temperature and precipitation varied by region. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, changes did not all occur at once. Generally however, studies found that temperatures were relatively warmer in the 11th century, but colder by the early 17th century. The degree of climate change which occurred in all regions across the world is uncertain, as is whether such changes were all part of a global trend.[42] Climate trends appear to be more recognizable in the Northern than in the Southern Hemisphere however, there are instances where climate in areas without written records have been estimated, historians now believe the Southern Hemisphere became colder between 950 and 1250.[43]

There are shorter climate periods that could be said roughly to account for large scale climate trends in the post-classical period. These include the Late Antique Little Ice Age, the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. The extreme weather events of 536–537 were likely initiated by the eruption of the Lake Ilopango caldera in El Salvador. Sulfate emitted into the air initiated global cooling, migrations and crop failures worldwide, possibly intensifying an already cooler time period.[44] Records show that the world's average temperature remained colder for at least a century afterwards.

The Medieval Warm Period from 950 to 1250 occurred mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, causing warmer summers in many areas; the high temperatures would only be surpassed by the global warming of the 20th/21st centuries. It has been hypothesized that the warmer temperatures allowed the Norse to colonize Greenland, due to ice-free waters. Outside of Europe there is evidence of warming conditions, including higher temperatures in China and major North American droughts which adversely affected numerous cultures.[45]

After 1250, glaciers began to expand in Greenland, affecting its thermohaline circulation, and cooling the entire North Atlantic. In the 14th century, the growing season in Europe became unreliable; meanwhile in China the cultivation of oranges was driven southward by colder temperatures. Especially in Europe, the Little Ice Age had great cultural ramifications.[46] It persisted until the Industrial Revolution, long after the post-classical period.[47] Its causes are unclear: possible explanations include sunspots, orbital cycles of the Earth, volcanic activity, ocean circulation, and man-made population decline.[48]

Timeline

[edit]This timetable gives a basic overview of states, cultures and events which transpired roughly between the years 200 and 1500. Sections are broken by political and geographic location.[49][50]

- Dates are approximate range (based upon influence), consult particular article for details

- Middle Ages Divisions, Middle Ages Themes Other themes

Eurasian trends

[edit]This section explains events and trends which affected the geographic area of Eurasia. The civilizations within this area were distinct from one another but still endured shared experiences and some development patterns.[51][52][53]

Feudalism

[edit]

In the context of global history, the label of feudalism has been used to describe any agricultural society where central authority broke down to be replaced by a warrior aristocracy. Feudal societies are characterized by reliance on personal relationships with military elites, rather than a bureaucracy with a state-supported professional standing army.[54] The label of feudalism has thus been used to describe many areas of Eurasia including medieval Europe, the Islamic iqta' system, Indian feudalism, and Heian Japan.[55] Some world historians generalize that societies can be called feudal if authority was fragmented, with a set of obligations between vassal and lord. After the 8th century, feudalism became more common across Europe. Even Byzantium, which had inherited the government of the Roman Empire, chose to devolve its military obligations into themes to increase the number of soldiers and ships available for military service during times of crisis.[56] There were similarities between European feudalism and the Islamic iqta', as both featured landed classes of mounted warriors whose titles were granted by a monarch or sultan.[57] Because of these similarities, it was common for societal structures to be preserved in the face of religious upheaval; for instance, after the Islamic Delhi Sultanate conquered large portions of India, it imposed higher taxes but otherwise left local feudal structures in place.[58]

Though most of Eurasia adopted feudalism and similar systems during this era, China employed a centralized bureaucracy throughout much of the post classical period, particularly after 1000.[59] A major factor that distinguished China from other regions was that local leaders were reluctant to self-identify by their current location; instead, they typically displayed an ambition to unite the country in times of disunity.[60]

Beyond a broad generalization, the usefulness of the term "feudalism" is debated by contemporary historians, as the daily functions of feudalism sometimes differed greatly between world regions.[54] Comparisons between feudal Europe and post-classical Japan have been particularly controversial. Throughout the 20th century, historians often compared medieval Europe to post-classical Japan.[61] More recently, it has been argued that, until roughly 1400, Japan balanced its decentralized military power with more centralized forms of imperial (governmental) and monastic (religious) authority. Only in the Sengoku period did there come to be fully decentralized power dominated by private military leaders.[62] Still other historians reject the term feudalism outright, challenging its ability to usefully describe societies either within or outside of medieval Europe.[63]

Mongol Empire

[edit]

The Mongol Empire, which existed during the 13th and 14th centuries, was the largest continuous land empire in history.[64] Originating in the steppes of Central Asia, the Mongol Empire eventually stretched from Central Europe to the Sea of Japan, extending northwards into Siberia, eastwards and southwards into the Indian subcontinent, Indochina, and the Iranian Plateau, and westwards as far as the Levant and Arabia.[65]

The Mongol Empire emerged from the unification of nomadic tribes in the Mongolia homeland under the leadership of Genghis Khan, who was proclaimed ruler of all Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and then under his descendants, who sent invasions in every direction.[66][67][68][69][70][71] The vast transcontinental empire connected east and west with an enforced Pax Mongolica allowing trade, technologies, commodities, and ideologies to be disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.[72][73]

The empire began to split due to wars over succession, as the grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from his son and initial heir Ögedei, or one of his other sons such as Tolui, Chagatai, or Jochi. After Möngke Khan died, rival kurultai councils simultaneously elected different successors, the brothers Ariq Böke and Kublai Khan, who then not only fought each other in the Toluid Civil War, but also dealt with challenges from descendants of other sons of Genghis.[74] Kublai successfully took power, but civil war ensued as Kublai sought unsuccessfully to regain control of the Chagatayid and Ögedeid families.[75]

The Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 marked the high-water point of the Mongol conquests and was the first time a Mongol advance had ever been beaten back in direct combat on the battlefield.[75] Though the Mongols launched many more invasions into the Levant, briefly occupying it and raiding as far as Gaza after a decisive victory at the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in 1299, they withdrew due to various geopolitical factors.

By the time of Kublai's death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest; the Chagatai Khanate in the west; the Ilkhanate in the southwest; and the Yuan dynasty based in modern-day Beijing.[76] In 1304, the three western khanates briefly accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Yuan dynasty,[77][78] but it was later overthrown by the Han Chinese Ming dynasty in 1368.[79] The Genghisid rulers returned to Mongolia homeland and continued rule in the Northern Yuan dynasty.[79] All of the original Mongol Khanates collapsed by 1500, but smaller successor states remained independent until the 1700s. Descendants of Chagatai Khan created the Mughal Empire that ruled much of India in early modern times.[79]

The conquests and the interactions the Mongol Empire had with western Eurasia are one of the more comprehensively researched areas for historians looking to define a globalized Middle Ages.[16]

Silk Road

[edit]

The Silk Road was a Eurasian trade route that played a large role in global communication and interaction. It stimulated cultural exchange; encouraged the learning of new languages; resulted in the trade of many goods, such as silk, gold, and spices; and also spread religion and disease.[80] It is even claimed by some historians – such as Andre Gunder Frank, William Hardy McNeill, Jerry H. Bentley, and Marshall Hodgson – that the Afro-Eurasian world was loosely united culturally, and that the Silk Road was fundamental to this unity.[80] This major trade route began with the Han dynasty of China, connecting it to the Roman Empire and any regions in between or nearby. At this time, Central Asia exported horses, wool, and jade into China for the latter's silk; the Romans would trade for the Chinese commodity as well, offering wine in return.[81] The Silk Road would often decline and rise again in trade from the Iron Age to the post-classical era. Following one such decline, it was reopened in Central Asia by Han dynasty general Ban Chao during the 1st century.[82]

There were vulnerabilities as well to changing political situations. The rise of Islam changed the Silk Road, because Muslim rulers generally closed the Silk Road to Christian Europe to an extent that Europe would be cut off from Asia for centuries. Specifically, the political developments that affected the Silk Road included the emergence of the Turks, the political movements of the Byzatine and Sasanian Empires, and the rise of the Arabs, among others.[83]

The Silk Road flourished again in the 13th century during the reign of the Mongol Empire, which through conquest had brought stability in Central Asia comparable to the Pax Romana.[84] It was claimed by a Muslim historian that Central Asia was peaceful and safe to transverse.

"(Central Asia) enjoyed such a peace that a man might have journeyed from the land of sunrise to the land of sunset with a golden platter upon his head without suffering the least violence from anyone."[85]

As such, trade and communication between Europe, East Asia, South Asia, and West Asia required little effort. Handicraft production, art, and scholarship prospered, and wealthy merchants enjoyed cosmopolitan cities. Notable Travelers including Ibn Battuta, Rabban Bar Sauma, and Marco Polo traveled across North Africa and Eurasia freely, those that left accounts of their experiences inspired future adventurers.[85] The Silk Road was also a major factor in spreading religion across Afro-Eurasia. Muslim teachings from Arabia and Persia reached East Asia. Buddhism spread from India, to China, to Central Asia. One significant development in the spread of Buddhism was the carving of the Gandhara School in the cities of ancient Taxila and the Peshwar, allegedly in the mid 1st century.[82] In addition to commercial travel was the esteem of pilgrimage that existed across all of Afro-Eurasia, in the words of world historian R. I. Moore "if any single institution 'made' the Eurasian Middle Ages it was pilgrimage."[53][86][87]

Nevertheless, after the 15th century, the Silk Road disappeared from regular use.[84] This was primarily a result from the growing sea travel pioneered by Europeans, which allowed the trade of goods by sailing around the southern tip of Africa and into the Indian Ocean.[84]

The route was vulnerable to spreading plague. The Plague of Justinian originated in East Africa and had a major outbreak in Europe in 542 causing the deaths of a quarter of the Mediterranean's population. Trade between Europe, Africa, and Asia along the route was at least partially responsible for spreading the plague.[88] Eight centuries later, the Silk Road trade played a role in spreading the infamous Black Death. The disease, spread by rats, was carried by merchant ships sailing across the Mediterranean that brought the plague back to Sicily, causing an epidemic in 1347.[89]

Plague and disease

[edit]In the Eurasian world, disease was an inescapable part of daily life. Europe in particular suffered minor outbreaks of disease every decade during the period. Using both land and sea routes, devastating pandemics could spread far beyond their initial focal point.[90] Tracking the origin of massive bubonic plagues and their potential spread between Eastern and Western Eurasia has been academically contentious.[91] Besides bubonic plague, other diseases including smallpox also spread across cultural regions.[92]

The first plague

[edit]The first plague pandemic caused by Yersinia pestis began with the 541–549 Plague of Justinian. The origin of the plague appears to have been the Tian Shan mountains in Kyrgyzstan.[93] But the origin of the 541–549 epidemic remains uncertain: some historians postulate East Africa as a possible geographical origin.[94]

There is no record of a disease with the characteristics of Yersinia pestis breaking out in China before its appearance in Pelusium Egypt. The plague spread to Europe and West Asia, with a possible spread into East Asia.[C] Established urban civilizations were massively depopulated; the economies and social fabric of established empires were severely destabilized.[96] Rural societies, while still facing horrific death tolls, saw fewer socioeconomic effects.[97] In addition, no evidence has been found of bubonic plague in India before 1600.[96] Nevertheless, it is likely that the trauma of disease (and other natural disasters) was a major cause of profound religious and political changes in Eurasia. Different authorities reacted to disease outbreaks with strategies that they believed would best protect their power. The Catholic Church in France spoke of healing miracles; Confucian bureaucrats asserted that sudden deaths of Chinese emperors represented the loss of a dynasty's Mandate of Heaven, shifting blame away from themselves. The severe loss of manpower in the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires contributed to early Muslim conquests in the region.[95] In the long term, overland trade in Eurasia diminished, as coastal Indian Ocean trade became more frequent. There were recurrent aftershocks of the Plague of Justinian until around 750, after which many nations saw an economic recovery.[98]

Second plague pandemic until 1500

[edit]

Six centuries later, a relative (but not a direct descendant) of Yersinia Pestis rose to afflict Eurasia: the Black Death. The first instance of the second plague pandemic was between 1347 and 1351. It killed variously between 25% and 50% of populations.[99] Traditionally many historians believed the Black Death started in China and was then spread westward by invading Mongols who inadvertently carried infected fleas and rats with them.[91] Although there is no concrete historical evidence for this theory, the plague is considered endemic on the steppe.[100] Currently there is extensive historiography of the Black Death's effects in Europe and the Islamic world, but beyond Western Eurasia direct evidence for Black Death's presence is lacking.[101][102] The Bulletin of the History of Medicine explored the potential linking of known 14th century epidemics in Asia with the plague. One example is the Deccan Plateau, where much of the Delhi Sultanate's army suddenly died of a sickness in 1334. As this was 15 years before Europe's Black Death but little detail about the symptoms, it is unlikely that this was an instance of bubonic plague. Meanwhile, Yuan China suffered from major epidemics in the mid-14th century, including a recorded 90% death rate in Hebei Province.[91] As with the Deccan event, surviving accounts do not describe symptoms; so historians are left to speculate.[91] Perhaps these outbreaks were not the Black Death but instead some other disease already common to East Asia at the time, such as typhus, smallpox, or dysentery.[91][103] Compared to Western reactions to the Black Death, Chinese records that do mention the epidemics are relatively muted, indicating that epidemics were a routine occurrence. Historians consider the hypothesis of a Chinese origin of a westward-moving plague unlikely given the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire and the 5,000-mile journey between China proper and Crimea through sparsely populated Central Asia.[91]

The aftershocks of the plague continued to affect populations well into the early modern period. In Western Europe, the devastating loss of people created lasting changes. Wage labor began to rise in Western Europe and there was more emphasis on labor-saving machines and mechanisms. Slavery, which had almost vanished from medieval Europe, returned and was one of the reasons for early Portuguese exploration after 1400. The adoption of Arabic numerals may have been partially caused by the plague.[104] Importantly, many economies became specialist, producing only certain goods, seeking expansion elsewhere for exotic resources and slave labor. While typically Western European expansion as a result of the Black Death is most discussed, Islamic countries including the Ottoman Empire also partook in land-based expansionism and used their own slave trade.[105]

Science

[edit]

The term post-classical science is often used in academic circles and in college courses to combine the study of medieval European science and medieval Islamic science due to their interactions with one another.[106] However scientific knowledge also spread westward by trade and war from Eastern Eurasia, particularly from China by Arabs. The Islamic world also took medical knowledge from South Asia.[107]

In the Western world and in Islamic realms, much emphasis was placed on preserving the rationalist Greek tradition of figures such as Aristotle. In the context of science within Islam there are questions as to whether Islamic scientists simply preserved accomplishments from classical antiquity or built upon earlier Greek advances.[108][109] Regardless, classical European science was brought back to the Christian kingdoms due to the experience of the Crusades.[110]

As a result of Persian trade in China, and the battle of the Talas River, Chinese innovations entered the Islamic intellectual world.[111] These include advances in astronomy and in papermaking.[112][113] Paper-making spread through the Islamic world as far west as Islamic Spain, before paper-making was acquired for Europe by the Reconquista.[114] There is debate about transmission of gunpowder regarding whether the Mongols introduced Chinese gunpowder weapons to Europe or whether gunpowder weapons were independently invented in Europe.[115][116] In the Mongol Empire, information from diverse cultures was brought together for large projects: for instance in 1303 the Mongol Yuan dynasty combined Chinese and Islamic cartography to make a map that likely included all of Eurasia including western Europe. This "Eurasia map" is now lost, but it influenced Chinese and Korean geographical knowledge centuries later.[103] It is apparent that within Eurasia transfer of information between world cultures did occur, usually through translations of written documents.[51]

Literature and the arts

[edit]

Within Eurasia, there were four major civilization groups that had literate cultures and created literature and arts, including Europe, West Asia, South Asia, and East Asia. Southeast Asia could be a possible fifth category but was influenced heavily from both South and East Asia literal cultures. All four cultures in post-classical times used poetry, drama, and prose. Throughout the period and until the 19th century poetry was the dominant form of literary expression. In West Asia, South Asia, Europe, and China, great poetic works often used figurative language. Examples include, the Sanskrit Shakuntala, the Arabic Thousand and one nights, Old English Beowulf and works by the Chinese Du Fu and the Persian Rumi. In Japan, prose uniquely thrived more than in other geographic areas. The Tale of Genji is considered the world's first realistic novel written in the 9th century.[117]

Musically, most regions of the world only used monophonic melodies as opposed to harmony. Medieval Europe was the lone exception to this rule, developing harmonic music in the 14th/15th century as musical culture transitioned form sacred music (meant for the church) to secular music.[118] South Asian and West Asian music were similar to each other for their use of microtone. East Asian music shared some similarities with European music by using twelve tones and employing scales, but differed in the number of scales used- 5 for the former and seven for the latter[119]

History by region

[edit]Africa

[edit]

During the post-classical era, Africa was both culturally and politically affected by the introduction of Islam and the Arab empires.[120] This was especially true in the north, the Sudan, and the east coast. However, this conversion was not complete nor uniform among different areas, and the low-level classes hardly changed their beliefs at all.[121] Prior to the migration and conquest of Muslims into Africa, much of the continent was dominated by diverse societies of varying sizes and complexities. These were ruled by kings or councils of elders who would control their constituents in a variety of ways. Most of these peoples practiced spiritual, animistic religions. Africa was culturally separated between Saharan Africa (which consisted of North Africa and the Sahara Desert) and sub-Saharan Africa (everything south of the Sahara). Sub-Saharan Africa was further divided into the Sudan, which covered everything north of Central Africa, including West Africa. The area south of the Sudan was primarily occupied by the Bantu peoples who spoke the Bantu language. From 1100 onward, Christian Europe and the Islamic world became dependent on Africa for gold.[122]

After approximately 650 urbanization expanded for the first time beyond the ancient kingdoms Aksum and Nubia. African civilizations can be divided into three categories based on religion:[123][124]

- Christian civilizations on the Horn of Africa

- Islamic civilizations which formed in the Niger River Valley and on the Swahili Coast

- Traditional societies which adhered to native African religions

Sub-Saharan Africa was part of two large, separate trading networks, the trans-Saharan trade that bridged commerce between West and North Africa. Due to the huge profits from trade native African Islamic empires arose, including those of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai.[125] In the 14th century, Mansa Musa of Mali may have been the wealthiest person of his time.[126] Within Mali, the city of Timbuktu was an international center of science and well known throughout the Islamic world, particularly from the University of Sankoré. East Africa was part of the Indian Ocean trade network, which included both Arab ruled Islamic cities on the East African Coast such as Mombasa and traditional cities such as Great Zimbabwe which exported gold, copper and ivory to markets in the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.[122]

Europe

[edit]

In Europe, Western civilization reconstituted after the fall of the Western Roman Empire into the period now known as the Early Middle Ages (500–1000). The Early Middle Ages saw a continuation of trends begun in late antiquity: depopulation, deurbanization, and increased barbarian invasion.[127]

From the 7th until the 11th centuries, Arabs, Magyars, and Norse were all threats to the Christian Kingdoms that killed thousands of people over centuries.[128] Raiders however, also created new trading networks.[129] In Western Europe, the Frankish king Charlemagne attempted to kindle the rise of culture and science in the Carolingian Renaissance.[130] In 800, Charlemagne founded the Holy Roman Empire in attempt to resurrect ancient Rome.[131] The reign of Charlemagne attempted to kindle a rise of learning and literacy in what has become known as the Carolingian Renaissance.[132]

In Eastern Europe, the Eastern Roman Empire survived in what is now called the Byzantine Empire, which created the Code of Justinian that inspired the legal structures of modern European states.[133] Overseen by Eastern Orthodox emperors, in the 9th–10th centuries the Byzantine Eastern Orthodox Church Christianized the First Bulgarian Empire and Kievan Rus', the cultural and political ancestors to modern-day Bulgaria and North Macedonia, on the one hand, and Russia and Ukraine, on the other.[134][135] Byzantium flourished as the leading power and trade center in its region in the Macedonian Renaissance until it was overshadowed by Italian city-states and the Islamic Ottoman Empire near the end of the Middle Ages.[136][137]

Later in the period, the creation of the feudal system allowed greater degrees of military and agricultural organization. There was sustained urbanization in northern and western Europe.[57] Later developments were marked by manorialism and feudalism, and evolved into the prosperous High Middle Ages.[57] After 1000 the Christian kingdoms that had emerged from Rome's collapse changed dramatically in their cultural and societal character.[129]

During the High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1300), Christian-oriented art and architecture flourished and the Crusades were mounted to recapture the Holy Land from Muslim control.[138] The influence of the emerging nation-state was tempered by the ideal of an international Christendom and the presence of the Catholic Church in all western kingdoms.[139] The codes of chivalry and courtly love set rules for proper behavior, while the Scholastic philosophers attempted to reconcile faith and reason.[110] The age of Feudalism would be dramatically transformed by the cataclysm of the Black Death and its aftermath.[140] This time would be a major underlying cause for the Renaissance. By the turn of the 16th century European or Western civilization would be engaging in the Age of Discovery.[141]

The term "Middle Ages" first appears in Latin in the 15th century and reflects the view that this period was a deviation from the path of classical learning, a path supposedly reconnected by Renaissance scholarship.[142]

West and Central Asia

[edit]The Arabian Peninsula and the surrounding Middle East and Near East regions saw dramatic change during the post-classical era caused primarily by the spread of Islam and the establishment of the Arab caliphates.[143]

In the 5th century, the Middle East was separated by empires and their spheres of influence; the two most prominent were the Persian Sasanian Empire, centered in what is now Iran, and the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). The Byzantines and Sasanians fought with each other continually, a reflection of the rivalry between the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire seen during the previous five hundred years.[144] The fighting weakened both states, leaving the stage open to a new power.[145] Meanwhile, the nomadic Bedouin tribes who dominated the Arabian desert saw a period of tribal warfare for scarce resources and a familiarity with Abrahamic religions or monotheism.[146]

While the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires were both weakened by the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, a new power in the form of Islam grew in the Middle East under Muhammad in Medina. In a series of rapid Muslim conquests, the Rashidun army, led by the caliphs and skilled military commanders such as Khalid ibn al-Walid, swept through most of the Middle East, taking more than half of Byzantine territory in the Arab–Byzantine wars and completely engulfing Persia in the Muslim conquest of Persia.[147] It would be the Arab caliphates of the Middle Ages that would first unify the entire Middle East as a distinct region and create the dominant ethnic identity that persists today. These caliphates included the Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid Caliphates, along with the later Turkic-based Seljuk Empire.[148]

After Muhammad introduced Islam, it jump-started Middle Eastern culture into an Islamic Golden Age, inspiring achievements in architecture, the revival of old advances in science and technology, and the formation of a distinct way of life.[149] Muslims saved and spread Greek advances in medicine, algebra, geometry, astronomy, anatomy, and ethics that would later find their way back to Western Europe.[150]

The dominance of the Arabs came to a sudden end in the mid-11th century with the arrival of the Seljuk Turks, migrating south from the Turkic homelands in Central Asia. They conquered Persia, Iraq (capturing Baghdad in 1055), Syria, Palestine, and the Hejaz.[151] This was followed by a series of Christian Western Europe invasions. The fragmentation of the Middle East allowed joint European forces mainly from England, France, and the emerging Holy Roman Empire, to enter the region.[152] In 1099 the knights of the First Crusade captured Jerusalem and founded the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which survived until 1187, when Saladin retook the city. Smaller crusader fiefdoms survived until 1291.[153] In the early 13th century, a new wave of invaders, the armies of the Mongol Empire, swept through the region, sacking Baghdad in the siege of Baghdad and advancing as far south as the border of Egypt in what became known as the Mongol conquests.[154] The Mongols eventually retreated in 1335, but the chaos that ensued throughout the empire deposed the Seljuk Turks. In 1401, the region was further plagued by the Turko-Mongol, Timur, and his ferocious raids. By then, another group of Turks had arisen as well, the Ottomans.[155]

South Asia

[edit]There has been difficulty applying the word "medieval" or "post-classical" to the history of South Asia. This section follows historian Stein Burton's definition that corresponds from the 8th century to the 16th century, more or less following the same time frame of the post-classical period and the European Middle Ages.[156]

Until the 13th century, there was no less than 20 to 40 different states on the Indian subcontinent which hosted a variety of cultures, languages, writing systems and religions.[157] At the beginning of the time period Buddhism was predominant throughout the area with the short-lived Pala Empire on the Indo-Gangetic Plain sponsoring the faith's institutions. One such institution was the Buddhist Nalanda mahavihara in modern-day Bihar, a center of scholarship that brought the divided South Asia onto the global intellectual stage. Another accomplishment was the invention of the Chaturanga game which later was exported to Europe and became chess.[158]

In South India, the Hindu kingdom of Chola gained prominence with an overseas empire that controlled parts of modern-day Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia as oversees territories and accelerated the spread of Hinduism into the historic culture of these places.[159] In this time period, neighboring areas such as Afghanistan, Tibet, and Myanmar were under South Asian influence.[160]

From 1206 onward, a series of Turkic invasions from modern-day Afghanistan and Iran conquered massive portions of North India, founding the Delhi Sultanate which remained supreme until the 16th century.[58] Buddhism declined in South Asia vanishing in many areas but Hinduism survived and reinforced itself in areas conquered by Muslims. In the far south, the Vijayanagara Empire was not conquered by any Muslim state in the period. The turn of the 16th century would see the rise of a new Islamic empire – the Mughals and the establishment of European trade posts by the Portuguese.[161]

Southeast Asia

[edit]

From the 8th century onward, Southeast Asia stood to benefit from the trade taking place between South Asia and East Asia, numerous kingdoms arose in the region due to the flow of wealth passing through the Strait of Malacca. While Southeast Asia had numerous outside influences including Indian and Chinese Civilization, local cultures strove to cement their own unique identities.[162] North Vietnam (known as Dai Viet) was culturally closer to China for centuries due to conquest.[163]

Since rule from the third century BCE, North Vietnam continued to be subjugated by Chinese states, although they continually resisted periodically. There were three periods of Chinese domination that spanned near 1100 years. The Vietnamese gained long lasting independence in the 10th century when China was divided with Tĩnh Hải quân and the successor Đại Việt. Nonetheless, even as an independent state a sort of begrudging Sinicization occurred. South Vietnam was governed by the ancient Hindu Champa Kingdom but was annexed by the Vietnamese in the 15th century.[164]

The spread of Hinduism, Buddhism, and maritime trade between China and South Asia created the foundation for Southeast Asia's first major empires; including the Khmer Empire from Cambodia and Srivijaya from Indonesia. During the Khmer Empire's height in the 12th century the city of Angkor Thom was among the largest of the pre-modern world due to its water management. King Jayavarman II constructed over a hundred hospitals throughout his realm.[165] Nearby rose the Pagan Empire in modern-day Burma, using elephants as military might.[166] The construction of the Buddhist Shwezigon Pagoda and its tolerance for believers of older polytheistic gods helped Theravada Buddhism become supreme in the region.[166] In Indonesia, Srivijaya from the 7th through 14th century was a thalassocracy that focused on maritime city states and trade. Controlling the vital choke points of the Sunda and Malacca Straits it became rich from trade ranging from Japan through Arabia.

Gold, ivory, and ceramics were all major commodities traveling through port cities. The empire was also responsible for the construction of wonders such as Borobudur. During this time Indonesian sailors crossed the Indian Ocean; evidence suggests that they may have colonized Madagascar.[167] Indian culture spread to the Philippines, likely through Indonesian trade resulting in the first documented use of writing in the archipelago and Indianized kingdoms.[168]

Over time, changing economic and political conditions elsewhere and wars weakened the traditional empires of Southeast Asia. While the Mongol invasions did not directly annex Southeast Asia, the war-time devastation paved way for the rise of new nations. In the 14th century the Khmer Empire was uprooted by persistent years of war - losing the functionality and engineering knowledge of its advanced water management system.[169] Srivijaya was overtaken by the Majapahit.[170] Islamic missionaries and merchants arrived eventually leading to Islamization in Indonesia.[171][D]

East Asia

[edit]

The time frame of 500–1500 in East Asia's history and China in particular has been proposed as a possible classification for the region's history within the context of global post-classical history.[173] Discussions within Columbia University's Association of Asian studies have postulated that similarities between China and other regions of Eurasia during post-classical times have often been overlooked.[174][E] Typically the English language histography of Japan postulates that its 'medieval period' began as late as 1185.[175][F]

During this period the Eastern empires continued to expand through trade, migration and conquests of neighboring areas. Japan and Korea went under the process of voluntary Sinicization, or the impression of Chinese cultural and political ideas.[176][177][178]

Korea and Japan sinicized because their ruling class were largely impressed by China's bureaucracy.[179] The major influences China had on these countries were the spread of Confucianism, the spread of Buddhism, and the establishment of centralized governance. Throughout East Asia, Buddhism was most visible in monasteries and local educational institutions and Confucianism remained the ideology of social cohesion and state power.[1]

[180] In the times of the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties (581–1279), China remained the world's largest economy and most technologically advanced society.[181][182] Inventions such as gunpowder, woodblock printing, and the magnetic compass were improved upon. China stood in contrast to other areas at the time as the imperial governments exhibited concentrated central authority instead of feudalism.[183]

China exhibited much interest in foreign affairs during the Tang and Song dynasties. From the 7th through the 10th centuries, Tang China was focused on securing the Silk Road as the selling of its goods westwards was central to the nation's economy.[179][184] For a time China successfully secured its frontiers by integrating their nomadic neighbors - the Göktürks - into their civilization.[185] The Tang dynasty expanded into Central Asia and received tribute from countries as distant as Eastern Iran.[179] Western expansion ended with wars with the Abbasid Caliphate and the deadly An Lushan Rebellion which resulted in a deadly but uncertain death toll of millions.[186] After the collapse of the Tang dynasty and subsequent civil wars came the second phase of Chinese interest in foreign relations. Unlike the Tang, the Song specialized in overseas trade and peacefully created a maritime network, and China's population became concentrated in the south.[187] Chinese merchant ships reached Indonesia, India, and Arabia. Southeast Asia's economy flourished from trade with Song China.[188]

With the country's emphasis on trade and economic growth. Song China's economy began to use machines to manufacture goods and coal as a source of energy.[189] The advances of the Song in the 11th/12th centuries have been considered an early industrial revolution.[190] Economic advancements came at the cost of military affairs and the Song became open to invasions from the north. China became divided as Song's northern lands were conquered by the Jurchen people.[191] By 1200, there were five Chinese kingdoms stretching from modern day Turkestan to the Sea of Japan including the Western Liao, Western Xia, Jin, Southern Song, and Dali.[192] Because these states competed with each other they all were eventually annexed by the rising Mongol Empire before 1279.[193] After seventy years of conquest, the Mongols proclaimed the Yuan dynasty and also subjugated Korea; they failed to conquer Japan.[194] Mongol conquerors also made China accessible to European travelers such as Marco Polo.[195] The Mongol era was short lived due to plagues and famine.[196] After the revolution in 1368, the succeeding Ming dynasty ushered in a period of prosperity and brief foreign expeditions before isolating itself from global affairs for centuries.[197]

Korea and Japan however continued to have relations with China and with other Asian countries. In the 15th century Sejong the Great of Korea cemented his country's identity by creating the Hangul writing system to replace use of Chinese characters.[198] Meanwhile, Japan fell under military rule of the Kamakura and later Ashikaga Shogunate dominated by the samurai.[199]

Oceania

[edit]-

Map of the Aboriginal regions in Australia.

Separate from developments in Afro-Eurasia and the Americas the region of greater Oceania continued to develop independently of the outside world. In Australia, the society of Aboriginal Australians changed little through the post-classical Period since their arrival in the area from Africa around 50,000 BCE. The only evidence of outside contact were encounters with fishermen of Indonesian origin.[G][200]

Polynesian and Micronesian peoples are rooted from Taiwan and Southeast Asia and began their migration into the Pacific Ocean from 3000 to 1500 BCE.[201] After the 4th century, the Micronesians and Polynesians began to explore the South Pacific and later constructed cities in previously uninhabited areas including Nan Madol Muʻa and others.[H][202] Around 1200 CE the Tuʻi Tonga Empire spread its influence far and wide throughout the South Pacific Islands, being described by academics as a maritime chiefdom which used trade networks to keep power centralized around the king's capital.[203] Polynesians on outrigger canoes discovered and colonized some of the last uninhabited islands of earth.[201] Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island were among the final places to be reached, settlers discovering pristine lands. Oral tradition claimed that navigator Ui-te-Rangiora discovered icebergs in the Southern Ocean.[204] In exploring and settling, Polynesian settlers did not strike at random but used their knowledge of wind and water currents to reach their destinations.[205]

On the settled islands some Polynesian groups became distinct from one another, a significant example being the Maori of New Zealand. Other island systems kept in contact with each other, including Hawaii and the Tahiti, goods in long-distance trade included basalt, and Pearl shell.[203] Ecologically, Polynesians had the challenge of sustaining themselves within limited environments. Some settlements caused mass extinctions of some native plant and animal species over time by hunting species such as the moa and introducing the Polynesian rat.[201] Easter Island settlers engaged in complete ecological destruction of their habitat and their population crashed afterwards possibly due to the construction of the Easter Island Statues.[206][207][208][209][I] Other colonizing groups adapted to accommodate to the ecology of specific islands such as the Moriori of the Chatham Islands.

Europeans on their voyages visited many Pacific islands in the 16th and 17th century, but most areas of Oceania were not colonized until after the voyages of British explorer James Cook in the 1780s.[211]

Americas

[edit]The post-classical era of the Americas can be considered set at a different time span from that of Afro-Eurasia. As the developments of Mesoamerican and Andean civilization differ greatly from that of the Old World, as well as the speed at which it developed, the post-classical era in the traditional sense does not take place until near the end of the medieval age in Western Europe.[J]

As such, for the purposes of this article, the Woodland period and Classic stage of the Americas will be discussed here, which takes place from about 400 to 1400.[214] For the technical post-classical stage in American development which took place on the eve of European contact, see Post-Classic stage.

North America

[edit]As a continent there was little unified trade or communication. Advances in agriculture spread northward from Mesoamerica indirectly through trade. Major cultural areas however still developed independently of each other.

Norse contact and the polar regions

[edit]

While there was little regular contact between the Americas and the Old World, the Norse explored and even colonized Greenland and Canada as early as 1000. None of these settlements survived past medieval times. Outside of Scandinavia knowledge of the discovery of the Americas was interpreted as a remote island or the North Pole.[215]

The Norse arriving from Iceland settled Greenland from approximately 980 to 1450.[216] The Norse arrived in southern Greenland prior to the 13th century approach of Inuit Thule people in the area. The extent of the interaction between the Norse and Thule is unclear.[216] Greenland was valuable to the Norse due to trade of ivory that came from the tusks of walruses. The Little Ice Age adversely affected the colonies and they vanished.[216] Greenland would be lost to Europeans until Danish Colonization in the 18th century.[217]

The Norse also explored and colonized farther south in Newfoundland, Canada at L'Anse aux Meadows referred to by the Norse as Vinland. The colony at most existed for twenty years and resulted in no known transmission of diseases or technology to the First Nations. To the Norse Vinland was known for plentiful grape vines to make superior wine. One reason for the colony's failure was constant violence with the native Beothuk people who the Norse referred to as skrælings.

After initial expeditions there is a possibility that the Norse continued to visit modern day Canada. Surviving records from medieval Iceland indicate some sporadic voyages to a land called Markland, possibly the coast of Labrador, Canada, as late as 1347 presumably to collect wood for deforested Greenland.[218]

Northern areas

[edit]

In North America, many hunter-gatherer and agricultural societies thrived in the diverse region. Native American tribes varied greatly in characteristics; some, including the Mound Builders and the Oasisamerican cultures were complex chiefdoms.[219] Other nations which inhabited the states of the modern northern United States and Canada had less complexity and did not follow technological changes as quickly. Approximately around the year 500 during the Woodland period, Native Americans began to transition to bows and arrows from spears for hunting and warfare.[220] Around the year 1,000 corn was widely adopted as a staple crop in the Eastern United States. Corn would continue to be the staple crop of natives in the Eastern United States and Canada until the Columbian exchange.[221][222]

In the Eastern United States, rivers were the medium of trade and communication. Cahokia located in the modern US state of Illinois was among the most significant city within the Mississippian culture.[219] Focused around Monks Mound archaeology indicates the population increased exponentially after 1000 because it manufactured important tools for agriculture and hosted cultural attractions.[223] Around 1350, Cahokia was abandoned with environmental factors having been proposed for the city's decline.[224]

At the same time, Ancestral Puebloans constructed clusters of buildings in the Chaco Canyon site located in the State of New Mexico. Individual houses may have been occupied by more than 600 residents at any one time. Chaco Canyon was the only pre-Columbian site in the United States to build paved roads.[225] Pottery indicates a society that was becoming more complex, turkeys for the first time in the continental United States were also domesticated. Around 1150 the structures of Chaco Canyon were abandoned, likely as a result of severe drought.[226][227][228] There were also other Pueblo complexes in the Southwestern United States like the Cliff Palace located in Mesa Verde National Park. After reaching climaxes native complex societies in the United States declined and did not entirely recover before the arrival of European explorers.[227][K]

Caribbean

[edit]

Concentrating a significant number of islands, the Caribbean had been the scene of constant maritime migrations via canoes since the Lithic stage, with its first inhabitants reaching the area by around 5000 BCE.[230]

After a millennium of population flows, the various peoples of the Caribbean entered in the post-classical period with notable developments on numerous permanent settlements and more complex social organizations, which were a result of the improvement of agricultural techniques and also the considerable growth of villages, that became great ceremonial and commercial centers led by different Cacique. Trading goods like shells, cotton, gold, colored stones and rare feathers were largely exported from island to island, ranging from the Lesser to the Great Antilles.[231]

By around 650 C.E and 800 C.E, new migratory waves from the Caribbean coast of present-day Venezuela took place and several people began a process of major cultural, sociopolitical, and ritual reformulations, which led to the formation of the first chiefdoms and the emergence of social hierarchy.[232] This period can also be described by the expulsion of the ancient Saladoid peoples from the main islands of the Caribbean and their subsequent replacement by the newly arrived Taíno people, who fiercely competed with other Arawak-speaking groups for arable land and war captives. Despite little evidence, some scholars still claim that the Taíno may have had a tenuous influence from the Maya civilization, as certain customs, such as the practice of batey, may have been inherited from the original Mesoamerican ballgame which also carried a religious character.[233]

When Christopher Columbus landed in the Bahamas in 1492, he and his crew initially maintained a peaceful contact with the local Taíno people, but soon afterwards they were enslaved by the Spanish colonizers, bringing the area into the early modern period.

Mesoamerica

[edit]

At the beginning of the global post-classical period, the city of Teotihuacan was at its zenith, housing over 125,000 people, at 500 AD it was the sixth largest city in the world at the time.[234] The city's residents built the Pyramid of the Sun the third largest pyramid of the world, oriented to follow astronomical events. In the 6th and 7th centuries, the city suddenly declined possibly as a result of severe environmental damage caused by extreme weather events of 535–536. There is evidence that large parts of the city were burned, possibly in a domestic rebellion.[235][L] The city's legacy would inspire all future civilizations in the region.[238]

At the same time was Classic Age of the Maya civilization clustered in dozens of city states on the Yucatán and modern day Guatemala.[239] The most significant of these cities was Chichen Itza which often fiercely competed with anywhere from 60 to 80 city states to be the dominant economic influence in the region.[240] Likewise, other Mayan cities such as Tikal and Calakmul also initiated a series of full-scale conflicts in the area over power and prestige, culminating in the Tikal-Calakmul Wars in the 6th century.[241]

The Mayans had an upper caste of priests, who were well versed in astronomy, mathematics, and writing. The Mayan developed the concept of zero, and a 365-day calendar which possibly pre-dates its creation in Old World societies.[242] After 900, many Mayan cities suddenly declined due to ecological disaster which was likely caused by a combination of drought and an incessant cycle of warfare, It's also been noted that classical Mayan Cities lacked food storage facilities.[213]

The Toltec Empire arose from the Toltec culture, and were remembered as wise and benevolent leaders. One priest-king called Ce Acatl Topiltzin advocated against human sacrifice.[243] After his death in 947, civil wars of religious character broke out between those who supported and opposed Topiltzin's teachings.[243] Modern historians however are skeptical of the extent of Toltec and influence and believe that much of the information known about the Toltecs was created by the later Aztecs as an inspiration myth.[244]

In the 1300s, a small band of violent, religious radicals called the Aztecs began minor raids throughout the area.[245] Eventually they began to claim connections with the Toltec civilization, and insisted they were the rightful successors.[246] They began to grow in numbers and conquer large areas of land. Fundamental to their conquest, was the use of political terror in the sense that the Aztec leaders and priests would command the human sacrifice of their subjugated people as means of humility and coercion.[245] Most of the Mesoamerican region would eventually fall under the Aztec Empire.[245] On the Yucatán Peninsula most of the Maya peoples continued to be independent of the Aztecs but their traditional civilization declined.[247] Aztec developments expanded cultivation, applying the use of chinampas, irrigation, and terrace agriculture; important crops included maize, sweet potatoes, and avocados.[245]

In 1430, the city of Tenochtitlan allied with other powerful Nahuatl-speaking cities, Texcoco and Tlacopan, to create the Aztec Empire, otherwise known as the Triple Alliance.[247] Though referred to as an empire the Aztec Empire functioned as a system of tribute collection with Tenochtitlan at its center. By the turn of the 16th century, "flower wars" between the Aztecs and rival states such as Tlaxcala had continued for over fifty years.[248]

South America

[edit]South American civilization was concentrated in the Andean region which had already hosted complex cultures since 2,500 BCE. East of the Andean region, societies were generally semi nomadic. Discoveries on the Amazon River Basin indicate the region likely had a pre-contact population of five million people and hosted complex societies.[249] Around the continent numerous agricultural peoples from Colombia to Argentina steadily advanced through numerous stages of development from 500 CE until European contact.[250]

Andes

[edit]

During ancient times, the Andes had developed civilizations independent of outside influences including that of Mesoamerica.[251] Through the Post Classical era a cycle of civilizations continued until Spanish contact. Collectively Andean societies lacked currency, a written language and solid draft animals enjoyed by old world civilizations. Instead Andeans developed other methods to foster their growth, including use of the quipu system to communicate messages, llamas to carry smaller loads and an economy based on reciprocity.[245] Societies were often based on strict social hierarchies and economic redistribution from the ruling class.[245]

In the first half of the post-classical period, the Andes was dominated by two almost equally powerful states. In the north of Peru was the Wari Empire and in the south of Peru and Bolivia there was the Tiwanaku Empire, both of whom were inspired by the earlier Moche people.[252] While the extent of their relationship to each other is unknown, it is believed that they competed with one another, but avoided direct conflict. Without war, there was prosperity and around the year 700 Tiwanaku city hosted a population of 1.4 million.[253] After the 8th century both states declined due to changing environmental conditions, laying the ground work for the Incas and other minor kingdoms to emerge as distinct cultures centuries later.[254]

In the 15th century, the Inca Empire rose to annex all other nations in the area. Led by their sun-god king, Sapa Inca, they slowly conquered what is now Peru, and built their society throughout the Andes cultural region. The Incas spoke the Quechua languages. Taking advantage of ancient advances left by previous Andean societies, the Incas were able to create the most advanced system of trade routes of South America, known as the Inca road system, which allowed greater interconnection between the conquered provinces.[255] Incas have been known to have used abacuses to calculate mathematics. The Inca Empire is known for some of its magnificent structures, such as Machu Picchu in the Cusco region.[256] The empire expanded quickly northwards to Ecuador, southwards to central Chile. To the north of the Inca Empire remained the independent Tairona and Muisca Confederation who practiced agriculture and gold metallurgy.[257][258]

End of the period

[edit]

As the post-classical era drew to a close in the 15th century, many of the empires established throughout the period were in decline.[259] The Byzantine Empire would soon be overshadowed in the Mediterranean by both Islamic and Christian rivals including Venice, Genoa, and the Ottoman Empire.[260] The Byzantines faced repeated attacks from eastern and western powers during the Fourth Crusade, and declined further until the loss of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453.[259]

The largest change came in terms of trade and technology. The global significance of the fall of the Byzantines was the disruption of overland routes between Asia and Europe.[261] Traditional dominance of nomadism in Eurasia declined and the Pax Mongolica which had allowed for interactions between different civilizations was no longer available. West Asia and South Asia were conquered by gunpowder empires which successfully used advances in military technology but closed the Silk Road.[M][262]

Europeans – specifically the Portuguese and various Italian explorers – intended to replace land travel with sea travel.[263] Originally European exploration merely looked for new routes to reach known destinations.[263] Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama traveled to India by sea in 1498 by circumnavigating Africa around the Cape of Good Hope.[264] India and the coast of Africa were already known to Europeans but none had attempted a large trading mission prior to that time.[264] Due to navigation advances Portugal would create a global colonial empire beginning with the conquest of Malacca in modern-day Malaysia from 1511.[265]

Other explorers such as the Spanish-sponsored Italian Christopher Columbus intended to engage in trade by traveling on unfamiliar routes west from Europe. The subsequent European discovery of the Americas in 1492 resulted in the Columbian exchange and the world's first pan-oceanic globalization.[266] Spanish explorer Ferdinand Magellan performed the first known circumnavigation of Earth in 1521.[267] The transfer of goods and diseases across oceans was unprecedented in creating a more connected world.[268] From developments in navigation and trade, modern history began.[266]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Post-Classical is often used to describe global history that took place during the time of the European Middle Ages (whose scope is entirely Euro-centric). The use of Post-Classical as a term for the period is sometimes disputed but is still used in academic circles.[4] This usage of Post-Classical 'World History' should not be confused with the Post-Classic period of Mesoamerica.

- ^ To expand further- Oceania, Afro Eurasia and the Americas were separated by hard oceanic barriers that prevented global interactions between them until the late 15th century. The existence of these three 'worlds' does not imply that all parts of each world-region were connected to themselves. In Afro-Eurasia for instance, South and Central Africa were certainly disconnected from the greater continental networks as were remote areas of Siberia.[28]

- ^ Historians befeore the 1980s often believed the Plague of Justinian that struck in 541 had an Asian origin. While it is possible that the disease itself was from modern-day Tajikistan it now seems that the opposite was true: the plague spread from West to East instead. There is little mention of 6th century epidemics in Asia before the plague had reached Byzantine Empire . The outbreak of 541 may have originated in Axum (Ethiopia) or elsewhere in East Africa. The plague apparently spread eastward from Byzantine Egypt. Persian armies invading Armenia were infected in 543. There was an outbreak of an unknown disease in the capital of southern China in 549. Central Asia was said to have been hit with "famine and disease" in 585. Outbreaks of disease in Central and East Asia continued and recurred for the next two centuries. After prolonged exposure to China, the first recorded epidemics in Korea and Japan were recorded in 698; it is probable but not certain that at least some of the epidemics east of Iran were bubonic.[95]

- ^ Islamization took place across different regions of Eurasia. However the Islamization that took place in maratime Southeast Asia contrast with that of Central Asia. In South East Asia the approach of Islam was a bottom-up process where certain individuals and groups began to convert due to perceived advantages. Meanwhile Central Asia's conversion was a top-down process.[171]

- ^ Within this model the greatest similarities that China had to Western Asia and Europe took place between 200–1000 CE. Similarities included both a breakdown in central authority (during the Three Kingdoms and Europe's Early Middle Ages) as well as the creation of large decentralized multi-ethnic empires (Tang Dynasty and Umayyad Caliphate).[60]

- ^ This corresponds with the end of the Gempi War and the establishment of the 'Shogun' title. The imperial dynasty and their civilian administration in Kyoto continued to exist but held little actual power. Japan would be under military control until 1868.[175]

- ^ Makassar people approached Australia on seasonal missions in search of Sea Cucumber, first arriving between 1500–1720, after the Post-Classical Period.

- ^ The growth of Polynesian settlement has been proposed as a possible start date for the entire era in world history[202]

- ^ The decline of Norse Greenland has been compared to that of Easter Island as both were isolated island societies that practiced deforestation.[210]

- ^ Furthermore how these terms are used depend on the location within the Americas being discussed. For example, the Late-Classic period in Measoamerica is categorized for the years 600-900, while Post Classical began after 900. For the continental United States, Post-Classical History began after 1200.[212][213]

- ^ Typically in North American archaeology the post classical era starts at 1200, differing from the world-history usage of the term and the Measoamerican context as well[229]

- ^ This weather event was worldwide as has been demonstrated by dendroclimatology, it was also documented by Byzantine historians.[236][237]

- ^ The use of 'closed' can be problematic because oftentimes Islamic regimes did not totally forbid Christian travel but would instead levy high tariffs. While some Europeans, including Venice, still took part in Eastern Mediterranean trade most Europeans were unwilling to pay tariffs in the long term.[262]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Kedar & Wiesner-Hanks 2015.

- ^ The Post‐Classical Era Archived 31 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Joel Hermansen

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stearns, Peter N. (2017). "Periodization in World History: Challenges and Opportunities". In R. Charles Weller (ed.). 21st-Century Narratives of World History: Global and Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Palgrave. ISBN 978-3-319-62077-0.

- ^ Bentley, Jerry H. (1996). "Cross-Cultural Interaction and Periodization in World History". The American Historical Review. 101 (3): 749–770. doi:10.1086/ahr/101.3.749. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ Thompson et al. 2009, p. 82.

- ^ Times Books 1998, p. 128.

- ^ Klein Goldewijk, Kees; Beusen, Arthur; Janssen, Peter (22 March 2010). "Long-term dynamic modeling of global population and built-up area in a spatially explicit way: HYDE 3.1". The Holocene. 20 (4): 565–573. Bibcode:2010Holoc..20..565K. doi:10.1177/0959683609356587. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 128905931.

- ^ Haub 1995, pp. 5–6: "The average annual rate of growth was actually lower from 1 A.D. to 1650 than the rate suggested above for the 8000 B.C. to 1 A.D. period. One reason for this abnormally slow growth was the Black Plague. This dreaded scourge was not limited to 14th century Europe. The epidemic may have begun about 542 A.D. in Western Asia, spreading from there. It is believed that half the Byzantine Empire was destroyed in the 6th century, a total of 100 million deaths.".

- ^ a b c Holmes & Standen 2018, p. 16.

- ^ Late antiquity: a guide to the postclassical world. 1 April 2000.

- ^ Rapp, Claudia; Drake, H.A., eds. (2014). "The City in the Classical and Post-Classical World". Cambridge University Press. pp. xv–xvi. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139507042.016 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISBN 978-1-139-50704-2.

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Evermon, Vandy. "Stafford Library: World History to 1500 – HIST 111 Resource Guide: Part 3 – 500 to 1500". library.ccis.edu. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ "Pre-AP World History and Geography – Pre-AP | College Board". pre-ap.collegeboard.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ Bentley, the Late Jerry H. (2012). Bentley, Jerry H (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of World History. Vol. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235810.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-923581-0.

- ^ a b c d Borgolte in Loud & Staub 2017, pp. 70–84

- ^ a b Holmes, Catherine (6 May 2021). "Global Middle Ages". The Later Middle Ages. Oxford University Press. pp. 195–219. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198731641.003.0008. ISBN 978-0-19-873164-1.

- ^ Loud & Staub 2017, pp. 1–13.

- ^ Geary in Loud & Staub 2017, pp. 57–69

- ^ Nelson in Loud & Staub 2017, pp. 17–36

- ^ Silverstein 2010, pp. 94–107.

- ^ Belich, Darwin & Wickham in Belich et al. 2016, pp. 3–22

- ^ William S. Atwell, 'Volcanism and Short-Term Climatic Change in East Asian and World History, c. 1200–1699 Archived 28 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine', Journal of World History, 12.1 (Spring 2001), 29–98.