Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sufism

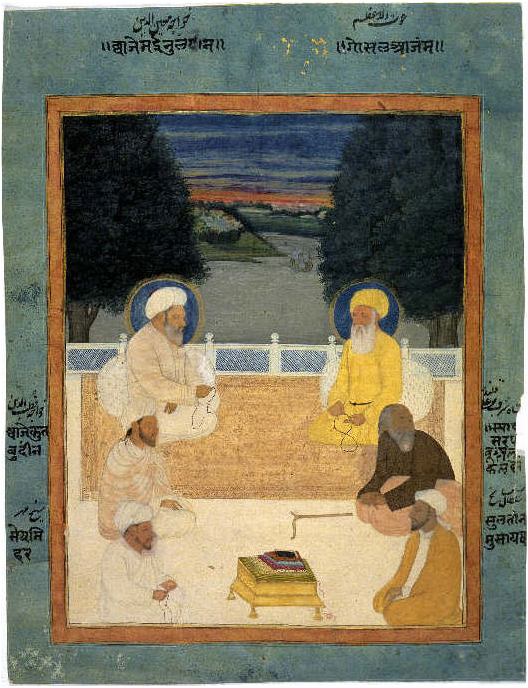

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

Sufism (Arabic: الصوفية, romanized: aṣ-Ṣūfiyya or Arabic: التصوف, romanized: at-Taṣawwuf) is a mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic purification, spirituality, ritualism, and asceticism.[1]

Practitioners of Sufism are referred to as "Sufis" (from صُوفِيّ, ṣūfīy),[2] and historically typically belonged to "orders" known as tariqa (pl. turuq) — congregations formed around a grand wali (saint) who would be the last in a chain of successive teachers linking back to Muhammad, with the goal of undergoing tazkiya (self purification) and the hope of reaching the spiritual station of ihsan.[3][4][5] The ultimate aim of Sufis is to seek the pleasure of God by endeavoring to return to their original state of purity and natural disposition, known as fitra.[6]

Sufism emerged early on in Islamic history, partly as a reaction against the expansion of the early Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) and mainly under the tutelage of Hasan al-Basri. Although Sufis were opposed to dry legalism, they strictly observed Islamic law and belonged to various schools of Islamic jurisprudence and theology.[7] Although the overwhelming majority of Sufis, both pre-modern and modern, remain adherents of Sunni Islam, certain strands of Sufi thought transferred over to the ambits of Shia Islam during the late medieval period.[8] This particularly happened after the Safavid conversion of Iran under the concept of irfan.[8] Important focuses of Sufi worship include dhikr, the practice of remembrance of God. Sufis also played an important role in spreading Islam through their missionary and educational activities.[7]

Despite a relative decline of Sufi orders in the modern era and attacks from fundamentalist Islamic movements (such as Salafism and Wahhabism), Sufism has continued to play an important role in the Islamic world.[9][10] It has also influenced various forms of spirituality in the West and generated significant academic interest.[11][12][13]

Definitions

[edit]The Arabic word tasawwuf (lit. ''Sufism''), generally translated as Sufism, is commonly defined by Western authors as Islamic mysticism.[14][15][16] The Arabic term Sufi has been used in Islamic literature with a wide range of meanings, by both proponents and opponents of Sufism.[14] Classical Sufi texts, which stressed certain teachings and practices of the Quran and the sunnah (exemplary teachings and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad), gave definitions of tasawwuf that described ethical and spiritual goals[note 1] and functioned as teaching tools for their attainment. Many other terms that described particular spiritual qualities and roles were used instead in more practical contexts.[14][15]

Some modern scholars have used other definitions of Sufism such as the "intensification of Islamic faith and practice"[14] and the "process of realizing ethical and spiritual ideals".[15]

The term Sufism was originally introduced into European languages in the 18th century by Orientalist scholars, who viewed it mainly as an intellectual doctrine and literary tradition at variance with what they saw as sterile monotheism of Islam. It was often mistaken as a universal mysticism in contrast to legalistic orthodox Islam.[17] In recent times, historian Nile Green has argued against such distinctions, stating, in the Medieval period Sufism and Islam were more or less the same.[18] In modern scholarly usage, the term serves to describe a wide range of social, cultural, political and religious phenomena associated with Sufis.[15]

Sufism has been variously defined as "Islamic mysticism",[19][20][21] "the mystical expression of Islamic faith",[22] "the inward dimension of Islam",[23][24] "the phenomenon of mysticism within Islam",[2][25] the "main manifestation and the most important and central crystallization" of mystical practice in Islam,[26][27] and "the interiorization and intensification of Islamic faith and practice".[28]

Etymology

[edit]The original meaning of ṣūfī seems to have been "one who wears wool (ṣūf)", and the Encyclopaedia of Islam calls other etymological hypotheses "untenable".[2][14] Woolen clothes were traditionally associated with ascetics and mystics.[2] Al-Qushayri and Ibn Khaldun both rejected all possibilities other than ṣūf on linguistic grounds.[29] Moreover, medieval scholars like Al Biruni believed that the term 'Sufi' gradually evolved from the Greek term σοφός (sophos), which means wisdom or knowledge.[30]

Another explanation traces the lexical root of the word to ṣafā (صفاء), which in Arabic means "purity", and in this context another similar idea of tasawwuf as considered in Islam is tazkiyah (تزكية, meaning: self-purification), which is also widely used in Sufism. These two explanations were combined by the Sufi al-Rudhabari (d. 322 AH), who said, "The Sufi is the one who wears wool on top of purity."[31][32]

Others have suggested that the word comes from the term Ahl al-Ṣuffa[33] ("the people of the suffah" or the bench), who were a group of impoverished companions of Muhammad who held regular gatherings of dhikr.[34] One of the most prominent companions among them was Abu Hurayra. These men and women who sat at the Prophet's Mosque are considered by some to be the first Sufis.[35][36]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The current consensus is that Sufism emerged in the Hejaz, present day Saudi Arabia and that it has existed as a practice of Muslims from the earliest days of Islam, even predating some sectarian divides.[37]

Sufi orders are based on the 'bayah (Arabic: بَيْعَة, lit. 'pledge') that was given to Muhammad by his companions (ṣahabah). By pledging allegiance to Muhammad, the sahabah had committed themselves to the service of God.[38][39][40]

Verily, those who give Bay'âh (pledge) to you (O Muhammad) they are giving Bay'âh (pledge) to God. The Hand of God is over their hands. Then whosoever breaks his pledge, breaks it only to his own harm, and whosoever fulfils what he has covenanted with God, He will bestow on him a great reward. — [Translation of Quran 48:10]

Sufis believe that by giving bayʿah (pledging allegiance) to a legitimate Sufi shaykh, one is pledging allegiance to Muhammad; therefore, a spiritual connection between the seeker and Muhammad is established. It is through Muhammad that Sufis aim to learn about, understand and connect with God.[41] Ali is regarded as one of the major figures amongst the sahaba who have directly pledged allegiance to Muhammad, and Sufis maintain that through Ali, knowledge about Muhammad and a connection with Muhammad may be attained. Such a concept may be understood by the hadith, which Sufis regard to be authentic, in which Muhammad said, "I am the city of knowledge, and Ali is its gate."[42] Eminent Sufis such as Ali Hujwiri refer to Ali as having a very high ranking in Tasawwuf. Furthermore, Junayd of Baghdad regarded Ali as sheikh of the principals and practices of Tasawwuf.[43]

Historian Jonathan A.C. Brown notes that during the lifetime of Muhammad, some companions were more inclined than others to "intensive devotion, pious abstemiousness and pondering the divine mysteries" more than Islam required, such as Abu Dharr al-Ghifari. Hasan al-Basri, a tabi', is considered a "founding figure" in the "science of purifying the heart".[44]

Sufism emerged early on in Islamic history,[2] partly as a reaction against the worldliness of the early Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) and mainly under the tutelage of Hasan al-Basri.[37]

Practitioners of Sufism hold that in its early stages of development Sufism effectively referred to nothing more than the internalization of Islam.[45] According to one perspective, it is directly from the Qur'an, constantly recited, meditated, and experienced, that Sufism proceeded, in its origin and its development.[46] Other practitioners have held that Sufism is the strict emulation of the way of Muhammad, through which the heart's connection to the Divine is strengthened.[47]

Later developments of Sufism occurred from people like Dawud Tai and Bayazid Bastami.[48] Early on Sufism was known for its strict adherence to the sunnah, for example it was reported Bastami refused to eat a watermelon because he did not find any proof that Muhammad ever ate it.[49][50] According to the late medieval mystic, the Persian poet Jami,[51] Abd-Allah ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah (died c. 716) was the first person to be called a "Sufi".[29] The term also had a strong connection with Kufa, with three of the earliest scholars to be called by the term being Abu Hashim al-Kufi,[52] Jabir ibn Hayyan and Abdak al-Sufi.[53] Later individuals included Hatim al-Attar, from Basra, and Al-Junayd al-Baghdadi.[53] Others, such as Al-Harith al-Muhasibi and Sari al-Saqati, were not known as Sufis during their lifetimes, but later came to be identified as such due to their focus on tazkiah (purification).[53]

Important contributions in writing are attributed to Uwais al-Qarani, Hasan of Basra, Harith al-Muhasibi, Abu Nasr as-Sarraj and Said ibn al-Musayyib.[48] Ruwaym, from the second generation of Sufis in Baghdad, was also an influential early figure,[54][55] as was Junayd of Baghdad; a number of early practitioners of Sufism were disciples of one of the two.[56]

Sufi orders

[edit]Historically, Sufis have often belonged to "orders" known as tariqa (pl. ṭuruq) – congregations formed around a grand master wali who will trace their teaching through a chain of successive teachers back to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[3]

Within the Sufi tradition, the formation of the orders did not immediately produce lineages of master and disciple. There are few examples before the eleventh century of complete lineages going back to the Prophet Muhammad. Yet the symbolic importance of these lineages was immense: they provided a channel to divine authority through master-disciple chains. It was through such chains of masters and disciples that spiritual power and blessings were transmitted to both general and special devotees.[57]

These orders meet for spiritual sessions (majalis) in meeting places known as zawiyas, khanqahs or tekke.[58]

They strive for ihsan (perfection of worship), as detailed in a hadith: "Ihsan is to worship Allah as if you see Him; if you can't see Him, surely He sees you."[59] Sufis regard Muhammad as al-Insān al-Kāmil, the complete human who personifies the attributes of Absolute Reality,[60] and view him as their ultimate spiritual guide.[61]

Sufi orders trace most of their original precepts from Muhammad through Ali ibn Abi Talib,[62] with the notable exception of the Naqshbandi order, which traces its original precepts to Muhammad through Abu Bakr.[63] However, it was not necessary to formally belong to a tariqa.[64] In the Medieval period, Sufism was almost equal to Islam in general and not limited to specific orders.[65](p24)

Sufism had a long history already before the subsequent institutionalization of Sufi teachings into devotional orders (tariqa, pl. tarîqât) in the early Middle Ages.[66] The term tariqa is used for a school or order of Sufism, or especially for the mystical teaching and spiritual practices of such an order with the aim of seeking ḥaqīqah (ultimate truth). A tariqa has a murshid (guide) who plays the role of leader or spiritual director. The members or followers of a tariqa are known as murīdīn (singular murīd), meaning "desirous", viz. "desiring the knowledge of knowing God and loving God".[67]

Over the years, Sufi orders have influenced and been adopted by various Shi'i movements, especially Isma'ilism, which led to the Safaviyya order's conversion to Shia Islam from Sunni Islam and the spread of Twelverism throughout Iran.[68]

Sufism as an Islamic discipline

[edit]

Existing in both Sunni and Shia Islam, Sufism is not a distinct sect, as is sometimes erroneously assumed, but a method of approaching or a way of understanding the religion, which strives to take the regular practice of the religion to the "supererogatory level" through simultaneously "fulfilling ... [the obligatory] religious duties"[2] and finding a "way and a means of striking a root through the 'narrow gate' in the depth of the soul out into the domain of the pure arid un-imprisonable Spirit which itself opens out on to the Divinity."[21] Academic studies of Sufism confirm that Sufism, as a separate tradition from Islam apart from so-called pure Islam, is frequently a product of Western orientalism and modern Islamic fundamentalists.[69]

As a mystic and ascetic aspect of Islam, it is considered as the part of Islamic teaching that deals with the purification of the inner self. By focusing on the more spiritual aspects of religion, Sufis strive to obtain direct experience of God by making use of "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use.[66] Tasawwuf is regarded as a science of the soul that has always been an integral part of Orthodox Islam. In his Al-Risala al-Safadiyya, ibn Taymiyyah describes the Sufis as those who belong to the path of the Sunna and represent it in their teachings and writings.[citation needed]

Ibn Taymiyya's Sufi inclinations and his reverence for Sufis like Abdul-Qadir Gilani can also be seen in his hundred-page commentary on Futuh al-ghayb, covering only five of the seventy-eight sermons of the book, but showing that he considered tasawwuf essential within the life of the Islamic community.[citation needed]

Al-Ghazali narrates in Al-Munqidh min al-dalal:

The vicissitudes of life, family affairs and financial constraints engulfed my life and deprived me of the congenial solitude. The heavy odds confronted me and provided me with few moments for my pursuits. This state of affairs lasted for ten years, but whenever I had some spare and congenial moments I resorted to my intrinsic proclivity. During these turbulent years, numerous astonishing and indescribable secrets of life were unveiled to me. I was convinced that the group of Aulia (holy mystics) is the only truthful group who follow the right path, display best conduct and surpass all sages in their wisdom and insight. They derive all their overt or covert behaviour from the illumining guidance of the holy Prophet, the only guidance worth quest and pursuit.[70]

Formalization of doctrine

[edit]

In the eleventh-century, Sufism, which had previously been a less "codified" trend in Islamic piety, began to be "ordered and crystallized" into orders which have continued until the present day. All these orders were founded by a major Islamic scholar, and some of the largest and most widespread included the Suhrawardiyya (after Abu al-Najib Suhrawardi [d. 1168]), Qadiriyya (after Abdul-Qadir Gilani [d. 1166]), the Rifa'iyya (after Ahmed al-Rifa'i [d. 1182]), the Chishtiyya (after Moinuddin Chishti [d. 1236]), the Shadiliyya (after Abul Hasan ash-Shadhili [d. 1258]), the Hamadaniyyah (after Sayyid Ali Hamadani [d. 1384]), the Naqshbandiyya (after Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari [d. 1389]).[71] Contrary to popular perception in the West,[72] however, neither the founders of these orders nor their followers ever considered themselves to be anything other than orthodox Sunni Muslims,[72] and in fact all of these orders were attached to one of the four orthodox legal schools of Sunni Islam.[73] Thus, the Qadiriyya order was Hanbali, with its founder, Abdul-Qadir Gilani, being a renowned jurist; the Chishtiyya was Hanafi; the Shadiliyya order was Maliki; and the Naqshbandiyya order was Hanafi.[74] Thus, it is precisely because it is historically proven that "many of the most eminent defenders of Islamic orthodoxy, such as Abdul-Qadir Gilani, Ghazali, and the Sultan Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn (Saladin) were connected with Sufism"[75] that the popular studies of writers like Idries Shah are continuously disregarded by scholars as conveying the fallacious image that "Sufism" is somehow distinct from "Islam".[76][75][77] Nile Green has observed that, in the Middle Ages, Sufism more or less was Islam.[65](p24)

Growth of influence

[edit]

Historically, Sufism became "an incredibly important part of Islam" and "one of the most widespread and omnipresent aspects of Muslim life" in Islamic civilization from the early medieval period onwards,[78][better source needed] when it began to permeate nearly all major aspects of Sunni Islamic life in regions stretching from India and Iraq to the Balkans and Senegal.[79][better source needed]

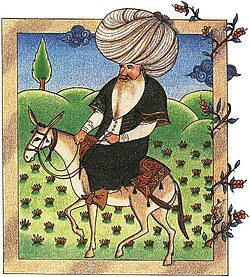

The rise of Islamic civilization coincides strongly with the spread of Sufi philosophy in Islam. The spread of Sufism has been considered a definitive factor in the spread of Islam, and in the creation of integrally Islamic cultures, especially in Africa[80] and Asia. The Senussi tribes of Libya and the Sudan are one of the strongest adherents of Sufism. Sufi poets and philosophers such as Khoja Akhmet Yassawi, Rumi, and Attar of Nishapur (c. 1145 – c. 1221) greatly enhanced the spread of Islamic culture in Anatolia, Central Asia, and South Asia.[81][82] Sufism also played a role in creating and propagating the culture of the Ottoman world,[83] and in resisting European imperialism in North Africa and South Asia.[84]

Between the 13th and 16th centuries, Sufism produced a flourishing intellectual culture throughout the Islamic world, a "Renaissance" whose physical artifacts survive.[citation needed] In many places a person or group would endow a waqf to maintain a lodge (known variously as a zawiya, khanqah, or tekke) to provide a gathering place for Sufi adepts, as well as lodging for itinerant seekers of knowledge. The same system of endowments could also pay for a complex of buildings, such as that surrounding the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, including a lodge for Sufi seekers, a hospice with kitchens where these seekers could serve the poor and/or complete a period of initiation, a library, and other structures. No important domain in the civilization of Islam remained unaffected by Sufism in this period.[87]

Modern era

[edit]Opposition to Sufi teachers and orders from more literalist and legalist strains of Islam existed in various forms throughout Islamic history. It took on a particularly violent form in the 18th century with the emergence of the Wahhabi movement.[88]

Around the turn of the 20th century, Sufi rituals and doctrines also came under sustained criticism from modernist Islamic reformers, liberal nationalists, and, some decades later, socialist movements in the Muslim world. Sufi orders were accused of fostering popular superstitions, resisting modern intellectual attitudes, and standing in the way of progressive reforms. Ideological attacks on Sufism were reinforced by agrarian and educational reforms, as well as new forms of taxation, which were instituted by Westernizing national governments, undermining the economic foundations of Sufi orders. The extent to which Sufi orders declined in the first half of the 20th century varied from country to country, but by the middle of the century the very survival of the orders and traditional Sufi lifestyle appeared doubtful to many observers.[89][88]

However, defying these predictions, Sufism and Sufi orders have continued to play a major role in the Muslim world, also expanding into Muslim-minority countries. Its ability to articulate an inclusive Islamic identity with greater emphasis on personal and small-group piety has made Sufism especially well-suited for contexts characterized by religious pluralism and secularist perspectives.[88]

In the modern world, the classical interpretation of Sunni orthodoxy, which sees in Sufism an essential dimension of Islam alongside the disciplines of jurisprudence and theology, is represented by institutions such as Egypt's Al-Azhar University and Zaytuna College, with Al-Azhar's current Grand Imam Ahmed el-Tayeb recently defining "Sunni orthodoxy" as being a follower "of any of the four schools of [legal] thought (Hanafi, Shafi’i, Maliki or Hanbali) and ... [also] of the Sufism of Imam Junayd of Baghdad in doctrines, manners and [spiritual] purification."[73]

The relationship of Sufi orders to modern societies is usually defined by their relationship to governments.[90]

Turkey, Persia and The Indian Subcontinent have all been a center for many Sufi lineages and orders. The Bektashi were closely affiliated with the Ottoman Janissaries and are the heart of Turkey's large and mostly liberal Alevi population. They have spread westwards to Cyprus, Greece, Albania, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and, more recently, to the United States, via Albania. Sufism is popular in such African countries as Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Sudan, Morocco, and Senegal, where it is seen as a mystical expression of Islam.[91] Mbacke suggests that one reason Sufism has taken hold in Senegal is because it can accommodate local beliefs and customs, which tend toward the mystical.[92]

The life of the Algerian Sufi master Abdelkader El Djezairi is instructive in this regard.[93] Notable as well are the lives of Amadou Bamba and El Hadj Umar Tall in West Africa, and Sheikh Mansur and Imam Shamil in the Caucasus. In the twentieth century, some Muslims have called Sufism a superstitious religion which holds back Islamic achievement in the fields of science and technology.[94]

A number of Westerners have embarked with varying degrees of success on the path of Sufism. One of the first to return to Europe as an official representative of a Sufi order, and with the specific purpose to spread Sufism in Western Europe, was the Swedish-born wandering Sufi Ivan Aguéli. René Guénon, the French scholar, became a Sufi in the early twentieth century and was known as Sheikh Abdul Wahid Yahya. His manifold writings defined the practice of Sufism as the essence of Islam, but also pointed to the universality of its message. Spiritualists, such as George Gurdjieff, may or may not conform to the tenets of Sufism as understood by orthodox Muslims.[95]

Aims and objectives

[edit]

While all Muslims believe that they are on the pathway to Allah and hope to become close to God in Paradise—after death and after the Last Judgment—Sufis also believe that it is possible to draw closer to God and to more fully embrace the divine presence in this life.[citation needed] The chief aim of all Sufis is to seek the pleasure of God by working to restore within themselves the primordial state of fitra.[6]

To Sufis, the outer law consists of rules pertaining to worship, transactions, marriage, judicial rulings, and criminal law—what is often referred to, broadly, as "qanun". The inner law of Sufism consists of rules about repentance from sin, the purging of contemptible qualities and evil traits of character, and adornment with virtues and good character.[96]

Teachings

[edit]

To the Sufi, it is the transmission of divine light from the teacher's heart to the heart of the student, rather than worldly knowledge, that allows the adept to progress. They further believe that the teacher should attempt inerrantly to follow the Divine Law.[97]

According to Moojan Momen "one of the most important doctrines of Sufism is the concept of al-Insan al-Kamil ("the Perfect Man"). This doctrine states that there will always exist upon the earth a "qutb" (pole or axis of the Universe)—a man who is the perfect channel of grace from God to man and in a state of wilayah (sanctity, being under the protection of Allah). The concept of the Sufi qutb is similar to that of the Shi'i imam.[98][99] However, this belief puts Sufism in "direct conflict" with Shia Islam, since both the qutb (who for most Sufi orders is the head of the order) and the imam fulfill the role of "the purveyor of spiritual guidance and of Allah's grace to mankind". The vow of obedience to the shaykh or qutb which is taken by Sufis is considered incompatible with devotion to the imam.[98]

As a further example, the prospective adherent of the Mevlevi Order would have been ordered to serve in the kitchens of a hospice for the poor for 1001 days prior to being accepted for spiritual instruction, and a further 1,001 days in solitary retreat as a precondition of completing that instruction.[100]

Some teachers, especially when addressing more general audiences, or mixed groups of Muslims and non-Muslims, make extensive use of parable, allegory, and metaphor.[101] Although approaches to teaching vary among different Sufi orders, Sufism as a whole is primarily concerned with direct personal experience, and as such has sometimes been compared to other, non-Islamic forms of mysticism (e.g., as in the books of Seyyed Hossein Nasr).

Many Sufi believe that to reach the highest levels of success in Sufism typically requires that the disciple live with and serve the teacher for a long period of time.[102] An example is the folk story about Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari, who gave his name to the Naqshbandi Order. He is believed to have served his first teacher, Sayyid Muhammad Baba As-Samasi, for 20 years, until as-Samasi died. He is said to then have served several other teachers for lengthy periods of time. He is said to have helped the poorer members of the community for many years, and after this concluded his teacher directed him to care for animals cleaning their wounds, and assisting them.[103]

Muhammad

[edit]His [Muhammad's] aspiration preceded all other aspirations, his existence preceded nothingness, and his name preceded the Pen, because he existed before all peoples. There is not in the horizons, beyond the horizons or below the horizons, anyone more elegant, more noble, more knowing, more just, more fearsome, or more compassionate, than the subject of this tale. He is the leader of created beings, the one "whose name is glorious Ahmad". —Mansur Al-Hallaj[104]

Devotion to Muhammad is the strongest practice within Sufism.[105] Sufis have historically revered Muhammad as the prime personality of spiritual greatness. The Sufi poet Saadi Shirazi stated, "He who chooses a path contrary to that of the prophet shall never reach the destination. O Saadi, do not think that one can treat that way of purity except in the wake of the chosen one."[106] Rumi attributes his self-control and abstinence from worldly desires as qualities attained by him through the guidance of Muhammad. Rumi states, "I 'sewed' my two eyes shut from [desires for] this world and the next – this I learned from Muhammad."[107] Ibn Arabi regards Muhammad as the greatest man and states, "Muhammad's wisdom is uniqueness (fardiya) because he is the most perfect existent creature of this human species. For this reason, the command began with him and was sealed with him. He was a Prophet while Adam was between water and clay, and his elemental structure is the Seal of the Prophets."[108] Attar of Nishapur claimed that he praised Muhammad in such a manner that was not done before by any poet, in his book the Ilahi-nama.[109] Fariduddin Attar stated, "Muhammad is the exemplar to both worlds, the guide of the descendants of Adam. He is the sun of creation, the moon of the celestial spheres, the all-seeing eye...The seven heavens and the eight gardens of paradise were created for him; he is both the eye and the light in the light of our eyes."[110] Sufis have historically stressed the importance of Muhammad's perfection and his ability to intercede. The persona of Muhammad has historically been and remains an integral and critical aspect of Sufi belief and practice.[105] Bayazid Bastami is recorded to have been so devoted to the sunnah of Muhammad that he refused to eat a watermelon because he could not establish that Muhammad ever ate one.[111]

In the 13th century, a Sufi poet from Egypt, Al-Busiri, wrote the al-Kawākib ad-Durrīya fī Madḥ Khayr al-Barīya ('The Celestial Lights in Praise of the Best of Creation'), commonly referred to as Qaṣīdat al-Burda ('Poem of the Mantle'), in which he extensively praised Muhammad.[112] This poem is still widely recited and sung amongst Sufi groups and lay Muslims alike all over the world.[112]

Sufi beliefs about Muhammad

[edit]According to Ibn Arabi, Islam is the best religion because of Muhammad.[60] Ibn Arabi regards that the first entity that was brought into existence is the reality or essence of Muhammad (al-ḥaqīqa al-Muhammadiyya). Ibn Arabi regards Muhammad as the supreme human being and master of all creatures. Muhammad is therefore the primary role model for human beings to aspire to emulate.[60] Ibn Arabi believes that God's attributes and names are manifested in this world and that the most complete and perfect display of these divine attributes and names are seen in Muhammad.[60] Ibn Arabi believes that one may see God in the mirror of Muhammad, meaning that the divine attributes of God are manifested through Muhammad.[60] Ibn Arabi maintains that Muhammad is the best proof of God, and by knowing Muhammad one knows God.[60] Ibn Arabi also maintains that Muhammad is the master of all of humanity in both this world and the afterlife. In this view, Islam is the best religion because Muhammad is Islam.[60]

Sufism and Islamic law

[edit]

Sufis believe the sharia (exoteric "canon"), tariqa ("order") and haqiqa ("truth") are mutually interdependent.[113] Sufism leads the adept, called salik or "wayfarer", in his sulûk or "road" through different stations (maqāmāt) until he reaches his goal, the perfect tawhid, the existential confession that God is One.[114] Ibn Arabi says, "When we see someone in this Community who claims to be able to guide others to God, but is remiss in but one rule of the Sacred Law—even if he manifests miracles that stagger the mind—asserting that his shortcoming is a special dispensation for him, we do not even turn to look at him, for such a person is not a sheikh, nor is he speaking the truth, for no one is entrusted with the secrets of God Most High save one in whom the ordinances of the Sacred Law are preserved. (Jamiʿ karamat al-awliyaʾ)".[115][116]

It is related, moreover, that Malik, one of the founders of the four schools of Sunni law, was a strong proponent of combining the "inward science" ('ilm al-bātin) of mystical knowledge with the "outward science" of jurisprudence.[117] For example, the famous twelfth-century Maliki jurist and judge Qadi Iyad, later venerated as a saint throughout the Iberian Peninsula, narrated a tradition in which a man asked Malik "about something in the inward science", to which Malik replied: "Truly none knows the inward science except those who know the outward science! When he knows the outward science and puts it into practice, God shall open for him the inward science – and that will not take place except by the opening of his heart and its enlightenment." In other similar traditions, it is related that Malik said: "He who practices Sufism (tasawwuf) without learning Sacred Law corrupts his faith (tazandaqa), while he who learns Sacred Law without practicing Sufism corrupts himself (tafassaqa). Only he who combines the two proves true (tahaqqaqa)".[117]

The Amman Message, a detailed statement issued by 200 leading Islamic scholars in 2005 in Amman, specifically recognized the validity of Sufism as a part of Islam. This was adopted by the Islamic world's political and temporal leaderships at the Organisation of the Islamic Conference summit at Mecca in December 2005, and by six other international Islamic scholarly assemblies including the International Islamic Fiqh Academy of Jeddah, in July 2006. The definition of Sufism can vary drastically between different traditions (what may be intended is simple tazkiah as opposed to the various manifestations of Sufism around the Islamic world).[118]

Traditional Islamic thought and Sufism

[edit]

The literature of Sufism emphasizes highly subjective matters that resist outside observation, such as the subtle states of the heart. Often these resist direct reference or description, with the consequence that the authors of various Sufi treatises took recourse to allegorical language. For instance, much Sufi poetry refers to intoxication, which Islam expressly forbids. This usage of indirect language and the existence of interpretations by people who had no training in Islam or Sufism led to doubts being cast over the validity of Sufism as a part of Islam. Also, some groups emerged that considered themselves above the sharia and discussed Sufism as a method of bypassing the rules of Islam in order to attain salvation directly. This was disapproved of by traditional scholars.

For these and other reasons, the relationship between traditional Islamic scholars and Sufism is complex, and a range of scholarly opinion on Sufism in Islam has been the norm. Some scholars, such as Al-Ghazali, helped its propagation while other scholars opposed it. William Chittick explains the position of Sufism and Sufis this way:

In short, Muslim scholars who focused their energies on understanding the normative guidelines for the body came to be known as jurists, and those who held that the most important task was to train the mind in achieving correct understanding came to be divided into three main schools of thought: theology, philosophy, and Sufism. This leaves us with the third domain of human existence, the spirit. Most Muslims who devoted their major efforts to developing the spiritual dimensions of the human person came to be known as Sufis.[49]

Persian influence on Sufism

[edit]Persians played a huge role in developing and systematising Islamic mysticism. One of the first to formalise Sufi principles was Junayd of Baghdad – a Persian from Baghdad.[119] Other great Persian Sufi poets include Rudaki, Rumi, Attar, Nizami, Hafez, Sanai, Shamz Tabrizi and Jami.[120] Famous poems that still resonate across the Muslim world include The Masnavi of Rumi, The Bustan by Saadi, The Conference of the Birds by Attar and The Divān of Hafez.

Neo-Sufism

[edit]

The term neo-Sufism was originally coined by Fazlur Rahman and used by other scholars to describe reformist currents among 18th century Sufi orders, whose goal was to remove some of the more ecstatic and pantheistic elements of the Sufi tradition and reassert the importance of Islamic law as the basis for inner spirituality and social activism.[13][11] In recent times, it has been increasingly used by scholars like Mark Sedgwick in the opposite sense, to describe various forms of Sufi-influenced spirituality in the West, in particular the deconfessionalized spiritual movements which emphasize universal elements of the Sufi tradition and de-emphasize its Islamic context.[11][12]

Devotional practices

[edit]

The devotional practices of Sufis vary widely. Prerequisites to practice include rigorous adherence to Islamic norms (ritual prayer in its five prescribed times each day, the fast of Ramadan, and so forth). Additionally, the seeker ought to be firmly grounded in supererogatory practices known from the life of Muhammad (such as the "sunnah prayers"). This is in accordance with the words, attributed to God, of the following, a famous Hadith Qudsi:

My servant draws near to Me through nothing I love more than that which I have made obligatory for him. My servant never ceases drawing near to Me through supererogatory works until I love him. Then, when I love him, I am his hearing through which he hears, his sight through which he sees, his hand through which he grasps, and his foot through which he walks.[121]

It is also necessary for the seeker to have a correct creed (aqidah),[122] and to embrace with certainty its tenets.[123] The seeker must also, of necessity, turn away from sins, love of this world, the love of company and renown, obedience to satanic impulse, and the promptings of the lower self. (The way in which this purification of the heart is achieved is outlined in certain books, but must be prescribed in detail by a Sufi master.) The seeker must also be trained to prevent the corruption of those good deeds which have accrued to his or her credit by overcoming the traps of ostentation, pride, arrogance, envy, and long hopes (meaning the hope for a long life allowing us to mend our ways later, rather than immediately, here and now).

Sufi practices, while attractive to some, are not a means for gaining knowledge. The traditional scholars of Sufism hold it as absolutely axiomatic that knowledge of God is not a psychological state generated through breath control. Thus, practice of "techniques" is not the cause, but instead the occasion for such knowledge to be obtained (if at all), given proper prerequisites and proper guidance by a master of the way. Furthermore, the emphasis on practices may obscure a far more important fact: The seeker is, in a sense, to become a broken person, stripped of all habits through the practice of (in the words of Imam Al-Ghazali) solitude, silence, sleeplessness, and hunger.[124]

Dhikr

[edit]

Dhikr is the remembrance of Allah commanded in the Quran for all Muslims through a specific devotional act, such as the repetition of divine names, supplications and aphorisms from hadith literature and the Quran. More generally, dhikr takes a wide range and various layers of meaning.[125] This includes dhikr as any activity in which the Muslim maintains awareness of Allah. To engage in dhikr is to practice consciousness of the Divine Presence and love, or "to seek a state of godwariness". The Quran refers to Muhammad as the very embodiment of dhikr of Allah (65:10–11). Some types of dhikr are prescribed for all Muslims and do not require Sufi initiation or the prescription of a Sufi master because they are deemed to be good for every seeker under every circumstance.[126]

The dhikr may slightly vary among each order. Some Sufi orders[127] engage in ritualized dhikr ceremonies, or sema. Sema includes various forms of worship such as recitation, singing (the most well known being the Qawwali music of the Indian subcontinent), instrumental music, dance (most famously the Sufi whirling of the Mevlevi order), incense, meditation, ecstasy, and trance.[128]

Some Sufi orders stress and place extensive reliance upon dhikr. This practice of dhikr is called Dhikr-e-Qulb (invocation of Allah within the heartbeats). The basic idea in this practice is to visualize the Allah as having been written on the disciple's heart.[129]

Muraqaba

[edit]

The practice of muraqaba can be likened to the practices of meditation attested in many faith communities.[130] While variation exists, one description of the practice within a Naqshbandi lineage reads as follows:

He is to collect all of his bodily senses in concentration, and to cut himself off from all preoccupation and notions that inflict themselves upon the heart. And thus he is to turn his full consciousness towards God Most High while saying three times: "Ilahî anta maqsûdî wa-ridâka matlûbî—my God, you are my Goal and Your good pleasure is what I seek". Then he brings to his heart the Name of the Essence—Allâh—and as it courses through his heart he remains attentive to its meaning, which is "Essence without likeness". The seeker remains aware that He is Present, Watchful, Encompassing of all, thereby exemplifying the meaning of his saying (may God bless him and grant him peace): "Worship God as though you see Him, for if you do not see Him, He sees you". And likewise the prophetic tradition: "The most favored level of faith is to know that God is witness over you, wherever you may be".[131]

Sufi whirling

[edit]

Sufi whirling (or Sufi spinning) is a form of Sama or physically active meditation which originated among some Sufis, and practised by the Sufi Dervishes of the Mevlevi order. It is a customary dance performed within the sema, through which dervishes (also called semazens, from Persian سماعزن) aim to reach the source of all perfection, or kemal. This is sought through abandoning one's nafs, egos or personal desires, by listening to the music, focusing on God, and spinning one's body in repetitive circles, which has been seen as a symbolic imitation of planets in the Solar System orbiting the Sun.[132]

As explained by Mevlevi practitioners:[133]

In the symbolism of the Sema ritual, the semazen's camel's hair hat (sikke) represents the tombstone of the ego; his wide, white skirt (tennure) represents the ego's shroud. By removing his black cloak (hırka), he is spiritually reborn to the truth. At the beginning of the Sema, by holding his arms crosswise, the semazen appears to represent the number one, thus testifying to God's unity. While whirling, his arms are open: his right arm is directed to the sky, ready to receive God's beneficence; his left hand, upon which his eyes are fastened, is turned toward the earth. The semazen conveys God's spiritual gift to those who are witnessing the Sema. Revolving from right to left around the heart, the semazen embraces all humanity with love. The human being has been created with love in order to love. Mevlâna Jalâluddîn Rumi says, "All loves are a bridge to Divine love. Yet, those who have not had a taste of it do not know!"

The traditional view of most orthodox Sunni Sufi orders, such as the Qadiriyya and the Chisti, as well as Sunni Muslim scholars in general, is that dancing with intent during dhikr or whilst listening to Sema is prohibited.[134][135][136][137]

Singing

[edit]Musical instruments (except the Daf) have traditionally been considered as prohibited by the four orthodox Sunni schools,[134][138][139][140][141] and the more orthodox Sufi tariqas also continued to prohibit their use. Throughout history most Sufi saints have stressed that musical instruments are forbidden.[134][142][143] However some Sufi Saints permitted and encouraged it, whilst maintaining that musical instruments and female voices should not be introduced, although these are common practice today.[134][142]

For example Qawwali was originally a form of Sufi devotional singing popular in the Indian subcontinent, and is now usually performed at dargahs. Sufi saint Amir Khusrau is said to have infused Persian, Arabic Turkish and Indian classical melodic styles to create the genre in the 13th century. The songs are classified into hamd, na'at, manqabat, marsiya or ghazal, among others.

Nowadays, the songs last for about 15 to 30 minutes, are performed by a group of singers, and instruments including the harmonium, tabla and dholak are used. Pakistani singing maestro Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan is credited with popularizing qawwali all over the world.[144]

Saints

[edit]

Walī (Arabic: ولي, plural ʾawliyāʾ أولياء) is an Arabic word whose literal meanings include "custodian", "protector", "helper", and "friend".[145] In the vernacular, it is most commonly used by Muslims to indicate an Islamic saint, otherwise referred to by the more literal "friend of God".[146][147][148] In the traditional Islamic understanding of saints, the saint is portrayed as someone "marked by [special] divine favor ... [and] holiness", and who is specifically "chosen by God and endowed with exceptional gifts, such as the ability to work miracles."[149] The doctrine of saints was articulated by Islamic scholars very early on in Muslim history,[150][151][2][152] and particular verses of the Quran and certain hadith were interpreted by early Muslim thinkers as "documentary evidence"[2] of the existence of saints.

Since the first Muslim hagiographies were written during the period when Sufism began its rapid expansion, many of the figures who later came to be regarded as the major saints in Sunni Islam were the early Sufi mystics, like Hasan of Basra (d. 728), Farqad Sabakhi (d. 729), Dawud Tai (d. 777-81), Rabi'a al-'Adawiyya (d. 801), Ma'ruf al-Karkhi (d. 815), and Junayd of Baghdad (d. 910). From the twelfth to the fourteenth century, "the general veneration of saints, among both people and sovereigns, reached its definitive form with the organization of Sufism ... into orders or brotherhoods."[153] In the common expressions of Islamic piety of this period, the saint was understood to be "a contemplative whose state of spiritual perfection ... [found] permanent expression in the teaching bequeathed to his disciples."[153]

Visitation

[edit]

In popular Sufism (i.e. devotional practices that have achieved currency in world cultures through Sufi influence), one common practice is to visit or make pilgrimages to the tombs of saints, renowned scholars, and righteous people. This is a particularly common practice in South Asia, where famous tombs include such saints as Sayyid Ali Hamadani in Kulob, Tajikistan; Afāq Khoja, near Kashgar, China; Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sindh; Ali Hujwari in Lahore, Pakistan; Bahauddin Zakariya in Multan Pakistan; Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer, India; Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi, India; and Shah Jalal in Sylhet, Bangladesh.

Likewise, in Fes, Morocco, a popular destination for such pious visitation is the Zaouia Moulay Idriss II and the yearly visitation to see the current sheikh of the Qadiri Boutchichi Tariqah, Sheikh Sidi Hamza al Qadiri al Boutchichi to celebrate the Mawlid (which is usually televised on Moroccan National television).[154][155] This action has voiced particular condemnation by the Salafis.

Miracles

[edit]In Islamic mysticism, karamat (Arabic: کرامات karāmāt, pl. of کرامة karāmah, lit. generosity, high-mindedness[156]) refers to supernatural wonders performed by Muslim saints. In the technical vocabulary of Islamic religious sciences, the singular form karama has a sense similar to charism, a favor or spiritual gift freely bestowed by God.[157] The marvels ascribed to Islamic saints have included supernatural physical actions, predictions of the future, and "interpretation of the secrets of hearts".[157] Historically, a "belief in the miracles of saints (karāmāt al-awliyāʾ, literally 'marvels of the friends [of God]')" has been "a requirement in Sunni Islam".[158]

Shrines

[edit]A dargah (Persian: درگاه dargâh or درگه dargah, also in Punjabi and Urdu) is a shrine built over the grave of a revered religious figure, often a Sufi saint or dervish. Sufis often visit the shrine for ziyarat, a term associated with religious visits and pilgrimages. Dargahs are often associated with Sufi eating and meeting rooms and hostels, called khanqah or hospices. They usually include a mosque, meeting rooms, Islamic religious schools (madrassas), residences for a teacher or caretaker, hospitals, and other buildings for community purposes.

Theoretical perspectives

[edit]

Traditional Islamic scholars have recognized two major branches within the practice of Sufism and use this as one key to differentiating among the approaches of different masters and devotional lineages.[159]

On the one hand there is the order from the signs to the Signifier (or from the arts to the Artisan). In this branch, the seeker begins by purifying the lower self of every corrupting influence that stands in the way of recognizing all of creation as the work of God, as God's active self-disclosure or theophany.[160] This is the way of Imam Al-Ghazali and of the majority of the Sufi orders.

On the other hand, there is the order from the Signifier to his signs, from the Artisan to his works. In this branch the seeker experiences divine attraction (jadhba), and is able to enter the order with a glimpse of its endpoint, of direct apprehension of the Divine Presence towards which all spiritual striving is directed. This does not replace the striving to purify the heart, as in the other branch; it simply stems from a different point of entry into the path. This is the way primarily of the masters of the Naqshbandi and Shadhili orders.[161]

Contemporary scholars may also recognize a third branch, attributed to the late Ottoman scholar Said Nursi and explicated in his vast Qur'an commentary called the Risale-i Nur. This approach entails strict adherence to the way of Muhammad, in the understanding that this wont, or sunnah, proposes a complete devotional spirituality adequate to those without access to a master of the Sufi way.[162]

Contributions to other domains of scholarship

[edit]Sufism has contributed significantly to the elaboration of theoretical perspectives in many domains of intellectual endeavor. For instance, the doctrine of "subtle centers" or centers of subtle cognition (known as Lataif-e-sitta) addresses the matter of the awakening of spiritual intuition.[163] In general, these subtle centers or latâ'if are thought of as faculties that are to be purified sequentially in order to bring the seeker's wayfaring to completion. A concise and useful summary of this system from a living exponent of this tradition has been published by Muhammad Emin Er.[159]

Sufi psychology has influenced many areas of thinking both within and outside of Islam, drawing primarily upon three concepts. Ja'far al-Sadiq (both an imam in the Shia tradition and a respected scholar and link in chains of Sufi transmission in all Islamic sects) held that human beings are dominated by a lower self called the nafs (self, ego, person), a faculty of spiritual intuition called the qalb (heart), and ruh (soul). These interact in various ways, producing the spiritual types of the tyrant (dominated by nafs), the person of faith and moderation (dominated by the spiritual heart), and the person lost in love for God (dominated by the ruh).[164]

Of note with regard to the spread of Sufi psychology in the West is Robert Frager, a Sufi teacher authorized in the Jerrahi order. Frager was a trained psychologist, born in the United States, who converted to Islam in the course of his practice of Sufism and wrote extensively on Sufism and psychology.[165][non-primary source needed]

Sufi cosmology and Sufi metaphysics are also noteworthy areas of intellectual accomplishment.[166]

Prominent Sufis

[edit]Rabi'a Al-'Adawiyya

[edit]

Rābiʼa al-ʼAdawiyya or Rabia Basri was a Sufi saint, one of the earliest Sufi mystics and an influential religious figure from Iraq.[167] Rabi'a was born of very poor origin, but was captured by bandits at a later age and sold into slavery. She was, however, released by her master when he awoke one night to see the light of sanctity shining above her head.[168] Prominent Sufi leader Hasan of Basra is said "I passed one whole night and day with Rabi'a ... it never passed through my mind that I was a man nor did it occur to her that she was a woman... when I saw her I saw myself as bankrupt and Rabi'a as truly sincere."[169] Rabi'a al-Adawiyya is known for her teachings and emphasis on the centrality of the love of God to a holy life.[170] She is said to have proclaimed, running down the streets of Basra, Iraq:

O God! If I worship You for fear of Hell, burn me in Hell, and if I worship You in hope of Paradise, exclude me from Paradise. But if I worship You for Your Own sake, grudge me not Your everlasting Beauty.

— Rabi'a al-Adawiyya

There are different opinions about the death and resting place of Rabia Basri. Some believe her resting place to be Jerusalem whereas others believe it to be Basra.[171][172]

Junayd of Baghdad

[edit]Junayd al-Baghdadi (830–910) was one of the earlier Sufis. He was a Persian Sufi and one of the most famous of the early Islamic saints and is a central figure in the spiritual lineages of many Sufi orders.[173][174] Junayd al-Baghdadi taught in Baghdad throughout his lifetime and was an important figure in the development of Sufi beliefs. Like Hasan of Basra before him, was widely revered by his students and disciples as well as quoted by other mystics. Because of his importance among Sufis, Junayd was often referred to as the "Sultan".[175]

Bayazid Bastami

[edit]Bayazid Bastami was a recognized and influential Sufi personality from the Tayfuriyya order.[176] Bastami was born in 804 in Bastam.[177] Bayazid is regarded for his devout commitment to the Sunnah and his dedication to fundamental Islamic principles and practices.

Shaykh Abdul Qadir Gilani

[edit]

Shaykh Abdul Qadir Gilani (1077–1166) was a Mesopotamian-born Hanbali jurist and prominent Sufi scholar based in Baghdad, with Persian roots. Gilani spent his early life in Na'if, a town just East of Baghdad, also the town of his birth. There, he pursued the study of Hanbali law. Abu Saeed Mubarak Makhzoomi gave Gilani lessons in fiqh. He was given lessons about hadith by Abu Bakr ibn Muzaffar. He was given lessons about Tafsir by Abu Muhammad Ja'far, a commentator. His Sufi spiritual instructor was Abu'l-Khair Hammad ibn Muslim al-Dabbas. After completing his education, Gilani left Baghdad. He spent twenty-five years as a reclusive wanderer in the desert regions of Iraq. In 1127, Gilani returned to Baghdad and began to preach to the public. He joined the teaching staff of the school belonging to his own teacher, Abu Saeed Mubarak Makhzoomi, and was popular with students. In the morning he taught hadith and tafsir, and in the afternoon held discourse on the science of the heart and the virtues of the Quran. He is the founder of the Qadiriyya order, of which its eponym is his patronym.[178]

Abul Hasan ash-Shadhili

[edit]Abul Hasan ash-Shadhili (died 1258) was the founder of the Shadhiliyya order, and introduced dhikr jahri (the remembrance of God out loud, as opposed to the silent dhikr). He taught that his followers need not abstain from what Islam has not forbidden, but to be grateful for what God has bestowed upon them,[179] in contrast to the majority of Sufis, who preach to deny oneself and to destroy the ego-self (nafs). The "Order of Patience" (Tariqus-Sabr), Shadhiliyya is formulated to be "Order of Gratitude" (Tariqush-Shukr). Imam Shadhili also gave eighteen valuable hizbs (litanies) to his followers, out of which the notable Hizb al-Bahr[180] is recited worldwide even today.

Moinuddin Chishti

[edit]

Moinuddin Chishti (1141–1236), known as Gharīb Nawāz ("Benefactor of the Poor"), was the most famous Sufi saint of the Chishti Order. Moinuddin Chishti introduced and established the order in the Indian subcontinent. The initial spiritual chain or silsila of the Chishti order in India, comprising Moinuddin Chishti, Bakhtiyar Kaki, Baba Farid, Nizamuddin Auliya (each successive person being the disciple of the previous one), constitutes the great Sufi saints of Indian history. Moinuddin Chishtī turned towards India, reputedly after a dream in which Muhammad blessed him to do so. After a brief stay at Lahore, he reached Ajmer along with Sultan Shahāb-ud-Din Muhammad Ghori, and settled down there. In Ajmer, he attracted a substantial following, acquiring a great deal of respect amongst the residents of the city. Moinuddin Chishtī practiced the Sufi Sulh-e-Kul (peace to all) concept to promote understanding between Muslims and non-Muslims.[181]

Bahauddin Naqshband

[edit]Bahauddin Naqshband (1318–1389) was a prominent Sufi master of the 14th century who founded the Naqshbandi Sufi order. Born in the village of Qasr-i Hinduvan near Bukhara, Uzbekistan, he was a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. His early life was marked by a deep spiritual inclination. He sought out the guidance of renowned Sufi teachers and quickly demonstrated exceptional talent and understanding. His primary teacher was Mohammad Baba As-Samasi, who initiated him into the spiritual path. His approach to Sufism emphasized inner contemplation, discipline, and a focus on the unseen. He advocated for a balanced lifestyle, combining spiritual practices with worldly responsibilities. His teachings were rooted in the Quran and the Sunnah, and he emphasized the importance of following the example of the Prophet Muhammad.

The Naqshbandi order became one of the most influential Sufi orders in Islamic history. It spread throughout Central Asia, the Middle East, and eventually to South Asia and the West. The order's emphasis on spiritual discipline, inner work, and social engagement resonated with many seekers.

Ahmad Al-Tijani

[edit]

Ahmed Tijani (1737–1815), in Arabic سيدي أحمد التجاني (Sidi Ahmed Tijani), was the founder of the Tijaniyya Sufi order. He was born in a Berber family,[182][183][184] in Aïn Madhi, present-day Algeria, and died at the age of 78 in Fez.[185][186]

Al-Ghazālī

[edit]al-Ghazali (c. 1058 – 1111) was a Sunni Muslim polymath.[187] He was a prominent Sufi, jurisconsult, legal theoretician, mufti, philosopher, theologian, logician and mystic.[188] He is considered to be the 11th century's mujaddid, a renewer of the faith, who appears once every 100 years.[189] Al-Ghazali's works were so highly acclaimed by his contemporaries that he was awarded the honorific title "Proof of Islam".[190] He was a prominent mujtahid in the Shafi'i school of law.[191] His magnum opus was Iḥyā’ ‘ulūm ad-dīn ("The Revival of the Religious Sciences").[192] His works include Tahāfut al-Falāsifa ("Incoherence of the Philosophers"), a landmark in the history of philosophy.[193]

Sayyed Badiuddin

[edit]Sayyid Badiuddin[194] was a Sufi saint who founded the Madariyya Silsila and order.[195] He was also known by the title Qutb-ul-Madar.[196]

He hailed originally from Syria, and was born in Aleppo[194] to a Syed Hussaini family.[197] His teacher was Bayazid Tayfur al-Bistami.[198] After making a pilgrimage to Medina, he journeyed to India to spread the Islamic faith, where he founded the Madariyya order.[196] His tomb is at Makanpur.[199]

Ibn Arabi

[edit]Ibn 'Arabi (or Ibn al-'Arabi) (AH 561 – AH 638; 1165–1240) was one of the most influential Sufis, revered for his profound spiritual insight, refined taste, and deep knowledge of God. Over the centuries, he has been honored with the title "The Grand Master" (Arabic: الشيخ الأكبر). Ibn Arabi founded the Sufi order known as "Al Akbariyya" (Arabic: الأكبرية), which remains active to this day. The order, based in Cairo, continues to spread his teachings and principles through its own sheikh. Ibn Arabi's writings, especially al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya and Fusus al-Hikam, have been studied within all Sufi orders as the clearest expression of tawhid (Divine Unity), though because of their recondite nature they were often only given to initiates. His teachings later became known as the school of wahdat al-wujud (the Oneness of Being). He himself considered his writings to have been divinely inspired. As he expressed the way to one of his close disciples, his legacy is that "you should never ever abandon your servant-hood (ubudiyya), and that there may never be in your soul a longing for any existing thing".[200]

Mansur Al-Hallaj

[edit]Mansur Al-Hallaj (died 922) is renowned for his claim, Ana-l-Haqq ("I am the Truth"), his ecstatic Sufism and state-trial. His refusal to recant this utterance, which was regarded as apostasy, led to a long trial. He was imprisoned for 11 years in a Baghdad prison, before being tortured and publicly beheaded on March 26, 922. He is still revered by Sufis for his willingness to embrace torture and death rather than recant. It is said that during his prayers, he would say "O Lord! You are the guide of those who are passing through the Valley of Bewilderment. If I am a heretic, enlarge my heresy".[201]

Yusuf Abu al-Haggag

[edit]Yusuf Abu al-Haggag (c. 1150 – c. 1245) was a Sufi scholar and sheikh preaching principally in Luxor, Egypt.[202] He devoted himself to knowledge, asceticism and worship.[203] In his pursuits, he earned the nickname "Father of the Pilgrim". His birthday is celebrated today annually in Luxor, with people convening at the Abu Haggag Mosque.

Notable Sufi works

[edit]Among the most popular Sufi works are:[204][205][206]

- Al-Ta'arruf li-Madhhab Ahl al-Tasawwuf (The Exploration of the Path of Sufis) by Abu Bakr al-Kalabadhi (d. ca. 380/990), a popular text about which 'Umar al-Suhrawardi (d. 632/1234) is reported to have said: "if it were not for the Ta'arruf, we would know nothing about Sufism".[207]

- Qūt al-Qulūb (Nourishment of the Hearts) by Abu Talib al-Makki (d. 386/996), an encyclopedic manual of Sufism (Islamic mystical teachings), which would have a significant influence on al-Ghazali's Ihya' 'Ulum al-Din (The Revival of the Religious Sciences).[208][209]

- Hilyat al-Awliya wa Tabaqat al-Asfiya (The Ornament of God's Friends and Generations of Pure Ones) by Abu Na'im al-Isfahani (d. 430/1038), which is a voluminous collection of biographies of Sufis and other early Muslim religious leaders.[210]

- Al-Risala al-Qushayriyya (The Qushayrian Treatise) by al-Qushayri (d. 465/1072), an indispensable reference book for those who study and specialize in Islamic mysticism. It is considered as one of the most popular Sufi manuals and has served as a primary textbook for many generations of Sufi novices to the present.[211]

- Ihya' 'Ulum al-Din (The Revival of the Sciences of Religion) by al-Ghazali (d. 505/1111). It is widely regarded as one of the most complete compendiums of Muslim thought and practice ever written, and is among the most influential books in the history of Islam. As its title indicates, it is a sustained attempt to put vigour and liveliness back into Muslim religious discourse.[212]

- Al-Ghunya li-Talibi Tariq al-Haqq (Sufficient Provision for Seekers of the Path of the Truth) by 'Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (d. 561/1166).[213][214] Translated from Arabic into English for the first time by Muhtar Holland.

- 'Awarif al-Ma'arif (The Gifts of Spiritual Perceptions) by Shihab al-Din 'Umar al-Suhrawardi (d. 632/1234), was one of the more popular Sufi books of his time, and posthumously it became the standard preparatory text book for Sufi novices around the Islamic world.[215][216]

- Al-Hikam al-'Ata'iyya (The Aphorisms of Ibn 'Ata' Allah) by Ibn 'Ata' Allah al-Sakandari (d. 709/1309), a collection of 261 Sufi aphorisms and proverbs (some counted it 264) containing precise contemplative reflections on man's relations with Allah (God), based on the teachings of the Qur'an and the Sunnah, and deals with issues related to tawhid (Islamic monotheism), ethics, morality and day-to-day conduct.[217]

Sufi commentaries on the Qur'an

[edit]Sufis have also made contributions to the Qur'anic exegetical literature, expounding the inner esoteric meanings of the Qur'an.[218][219] Among such works are the following:[220]

- Tafsir al-Qu'ran al-'Azim (Interpretation of the Great Qur'an) by Sahl al-Tustari (d. 283/896),[221] the oldest Sufi commentary on the Qur'an.[222]

- Lata'if al-Isharat (Subtleties of the Allusions) by al-Qushayri (d. 465/1072).[223]

- 'Ara'is al-Bayan fi Haqa'iq aI-Qur'an (The Brides of Explication Concerning the Hidden Realities of the Qur'an) by Ruzbihan al-Baqli (d. 606/1209).

- Al-Ta'wilat al-Najmiyya (Starry Interpretations) by Najm al-Din Kubra (d. 618/1221). This is a jointly-authored work, started by Najm al-Din Kubra, followed by his student Najm al-Din Razi (d. 654/1256) and finished by 'Alā' al-Dawla al-Simnani (d. 736/1336).[224]

- Ghara'ib al-Qur'an wa Ragha'ib al-Furqan (Wonders of the Qur'an and Desiderata of the Criterion) by Nizam al-Din al-Nisaburi (d. ca. 728/1328).

- Anwar al-Qur'an wa Asrar al-Furqan (Lights of the Qur'an and Secrets of the Criterion) by Mulla 'Ali al-Qari (d. 1014/1606).

- Ruh al-Bayan fi Tafsir al-Qur'an (The Spirit of Explanation in the Commentary on the Qur'an) by Isma'il Haqqi al-Brusawi/Bursevi (d. 1137/1725).[225] He started this voluminous Qur'anic commentary and completed it in twenty-three years.[226]

- Al-Bahr al-Madeed fi Tafsir al-Qur'an al-Majeed (The Vast Sea in the Interpretation of the Glorious Qur'an) by Ahmad ibn 'Ajiba (d. 1224/1809).

Reception

[edit]Persecution of Sufi Muslims

[edit]

The persecution of Sufism and Sufi Muslims over the course of centuries has included acts of religious discrimination, persecution and violence, such as the destruction of Sufi shrines, tombs, and mosques, suppression of Sufi orders, and discrimination against adherents of Sufism in a number of Muslim-majority countries.[230] The Republic of Turkey banned all Sufi orders and abolished their institutions in 1925, after Sufis opposed the new secular order. The Islamic Republic of Iran has harassed Shia Sufis, reportedly for their lack of support for the government doctrine of "governance of the jurist" (i.e., that the supreme Shiite jurist should be the nation's political leader).

In most other Muslim-majority countries, attacks on Sufis and especially their shrines have come from adherents of puritanical fundamentalist Islamic movements (Salafism and Wahhabism), who believe that practices such as visitation to and veneration of the tombs of Sufi saints, celebration of the birthdays of Sufi saints, and dhikr ("remembrance" of God) ceremonies are bid‘ah (impure "innovation") and shirk ("polytheistic").[230][231][232][233][234]

In Egypt, at least 305 people were killed and more than 100 wounded during the November 2017 Islamic terrorist attack on a Sufi mosque located in Sinai; it is considered one of the worst terrorist attacks in the history of modern Egypt.[231][235] Most of the victims were Sufis.[231][235]

Perception outside Islam

[edit]

Sufi mysticism has long exercised a fascination upon the Western world, and especially its Orientalist scholars.[236] In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European orientalists treated Sufism and Islam as distinct subjects, leading to "an over-emphasis on the translation of classical Sufi mystical literature" in the academic study of Sufism at the expense of the lived practices in Islam, as well as a separation of Sufism from its Islamic roots in the development of Sufism as a religious form in the West.[237][238] Figures like Rumi have become well known in the United States, where Sufism is perceived as a peaceful and apolitical form of Islam.[236][239] Seyyed Hossein Nasr states that the preceding theories are false according to the point of view of Sufism.[240]

The Islamic Institute in Mannheim, Germany, which works towards the integration of Europe and Muslims, sees Sufism as particularly suited for interreligious dialogue and intercultural harmonisation in democratic and pluralist societies; it has described Sufism as a symbol of tolerance and humanism—nondogmatic, flexible and non-violent.[241] According to Philip Jenkins, a professor at Baylor University, "the Sufis are much more than tactical allies for the West: they are, potentially, the greatest hope for pluralism and democracy within Muslim nations." Likewise, several governments and organisations have advocated the promotion of Sufism as a means of combating intolerant and violent strains of Islam.[242] For example, the Chinese and Russian[243] governments openly favor Sufism as the best means of protecting against Islamist subversion. The British government, especially following the 7 July 2005 London bombings, has favoured Sufi groups in its battle against Muslim extremist currents. The influential RAND Corporation, an American think-tank, issued a major report titled "Building Moderate Muslim Networks", which urged the US government to form links with and bolster[244] Muslim groups that opposed Islamist extremism. The report stressed the Sufi role as moderate traditionalists open to change, and thus as allies against violence.[245][246] News organisations such as the BBC, Economist and Boston Globe have also seen Sufism as a means to deal with violent Muslim extremists.[247]

Idries Shah states that Sufism is universal in nature, its roots predating the rise of Islam and Christianity.[248] He quotes Suhrawardi as saying that "this (Sufism) was a form of wisdom known to and practiced by a succession of sages including the mysterious ancient Hermes of Egypt.", and that Ibn al-Farid "stresses that Sufism lies behind and before systematization; that 'our wine existed before what you call the grape and the vine' (the school and the system)..."[249] Shah's views have however been rejected by modern scholars.[7] Such modern trends of neo-Sufis in Western countries allow non-Muslims to receive "instructions on following the Sufi path", not without opposition by Muslims who consider such instruction outside the sphere of Islam.[250]

Similarities with Eastern religions

[edit]Numerous comparisons have been made between Sufism and the mystic components of some Eastern religions.

The tenth-century Persian polymath Al-Biruni in his book Tahaqeeq Ma Lilhind Min Makulat Makulat Fi Aliaqbal Am Marzula (Critical Study of Indian Speech: Rationally Acceptable or Rejected) discusses the similarity of some Sufism concepts with aspects of Hinduism, such as: Atma with ruh, tanasukh with reincarnation, Mokhsha with Fanafillah, Ittihad with Nirvana: union between Paramatma in Jivatma, Avatar or Incarnation with Hulul, Vedanta with Wahdatul Ujud, Mujahadah with Sadhana.[citation needed]

Other scholars have likewise compared the Sufi concept of Waḥdat al-Wujūd to Advaita Vedanta,[251] Fanaa to Samadhi,[252] Muraqaba to Dhyana, and tariqa to the Noble Eightfold Path.[253]

The ninth-century Iranian mystic Bayazid Bostami is alleged to have imported certain concepts from Hindusim into his version of Sufism under the conceptual umbrella of baqaa, meaning perfection.[254] Ibn al-Arabi and Mansur al-Hallaj both referred to Muhammad as having attained perfection and titled him as Al-Insān al-Kāmil.[255][256][257][258][259][260] Inayat Khan believed that the God worshipped by Sufis is not specific to any particular religion or creed, but is the same God worshipped by people of all beliefs. This God is not limited by any name, whether it be Allah, God, Gott, Dieu, Khuda, Brahma, or Bhagwan.[261]

Buddhist stories also circulated in Sufi circles. One of them being a story about blind men trying to describe an elephant.[262]

Influence on Judaism

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (July 2017) |

There is evidence that Sufism influenced the development of some schools of Jewish philosophy and ethics. In the first writing of this kind, we see Kitab al-Hidayah ila Fara'iḍ al-Ḳulub, Duties of the Heart, of Bahya ibn Paquda. This book was translated by Judah ibn Tibbon into Hebrew under the title Chovot HaLevavot.[263]

The precepts prescribed by the Torah number 613 only; those dictated by the intellect are innumerable.

— Kremer, Alfred Von. 1868. "Notice sur Sha‘rani". Journal Asiatique 11 (6): 258.

In the ethical writings of the Sufis Al-Kusajri and Al-Harawi there are sections which treat of the same subjects as those treated in the Chovot ha-Lebabot and which bear the same titles: e.g., "Bab al-Tawakkul"; "Bab al-Taubah"; "Bab al-Muḥasabah"; "Bab al-Tawaḍu'"; "Bab al-Zuhd". In the ninth gate, Baḥya directly quotes sayings of the Sufis, whom he calls Perushim. However, the author of the Chovot HaLevavot did not go so far as to approve of the asceticism of the Sufis, although he showed a marked predilection for their ethical principles.

Abraham Maimonides, the son of the Jewish philosopher Maimonides, believed that Sufi practices and doctrines continue the tradition of the biblical prophets.[264]

Abraham Maimonides' principal work was originally composed in Judeo-Arabic and entitled "כתאב כפאיה אלעאבדין" Kitāb Kifāyah al-'Ābidīn (A Comprehensive Guide for the Servants of God). From the extant surviving portion it is conjectured that the treatise was three times as long as his father's Guide for the Perplexed. In the book, he evidences a great appreciation for, and affinity to, Sufism. Followers of his path continued to foster a Jewish-Sufi form of pietism for at least a century, and he is rightly considered the founder of this pietistic school, which was centered in Egypt.[265]

The followers of this path, which they called Hasidism (not to be confused with the [later] Jewish Hasidic movement) or Sufism (Tasawwuf), practiced spiritual retreats, solitude, fasting and sleep deprivation. The Jewish Sufis maintained their own brotherhood, guided by a religious leader like a Sufi sheikh.[266]

The Jewish Encyclopedia, in its entry on Sufism, states that the revival of Jewish mysticism in Muslim countries is probably due to the spread of Sufism in the same geographical areas. The entry details many parallels to Sufic concepts found in the writings of prominent Kabbalists during the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain.[267][268]

Culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]

The 13th century Persian poet Rumi is considered one of the most influential figures of Sufism, as well as one of the greatest poets of all time. He has become one of the most widely read poets in the United States, thanks largely to the interpretative translations published by Coleman Barks.[269] Elif Şafak's novel The Forty Rules of Love is a fictionalized account of Rumi's encounter with the Persian dervish Shams Tabrizi.[270]

Muhammad Iqbal, one of the greatest Urdu poets, has discussed Sufism, philosophy and Islam in his English work The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam.[271][non-primary source needed]

Sama

[edit]Sama is regarded as an important element in different Sufi orders. In South Asia, it is affiliated mostly with Chishti Order. It develops into a distinct art form, especially during the reign of Khwaja Amir Khusrau and his contemporary Sufi masters, such as Khwaja Nizamuddin Auliya and others.[272] Spiritual experiences were desired by Sufis through Sama, listening to poetry or Islamic mystical verses with the use of different musical instruments, aiming to attain ecstasy in divine love of Allah and his Prophet.[273]

Visual art

[edit]Many painters and visual artists have explored the Sufi motif through various disciplines. One of the outstanding pieces in the Brooklyn Museum's Islamic gallery has been the museum's associate curator of Islamic art, is a large 19th- or early-20th-century portrayal of the Battle of Karbala painted by Abbas Al-Musavi,[274] which was a violent episode in the disagreement between the Sunni and Shia branches of Islam; during this battle, Husayn ibn Ali, a pious grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, died and is considered a martyr in Islam.[275]

In July 2016, at International Sufi Festival held in Noida Film City, UP, India, H.E. Abdul Basit who was the High Commissioner of Pakistan to India at that time, while inaugurating the exhibition of Farkhananda Khan ‘Fida’ said, "There is no barrier of words or explanation about the paintings or rather there is a soothing message of brotherhood, peace in Sufism".[276]

Scientific research

[edit]A systematic review published in 2023 examined the relationship between Islamic-Sufi spirituality and mental health outcomes, revealing a positive connection between Sufi spirituality and reductions in anxiety and depression among patients.[277]

A study on political Sufism in contemporary Kazakhstan examined patterns of religious continuity and the role of Sufi networks in political mobilization.[278]

An overview of Sufi studies at American universities indicated that Sufism has become a significant area of scholarly inquiry, with dedicated programs and research centers focusing on its various aspects.[279]

Recent bibliometric analyses have also mapped the intellectual structure and global trends in Sufi studies.[280]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The following are among definitions of Sufism quoted in an early Sufi treatise by Abu Nasr as-Sarraj:

• "Sufism is that you should be with God—without any attachment." (Junayd of Baghdad)

• "Sufism consists of abandoning oneself to God in accordance with what God wills." (Ruwaym ibn Ahmad)

• "Sufism is that you should not possess anything nor should anything possess you." (Samnun)

• "Sufism consists of entering every exalted quality (khulq) and leaving behind every despicable quality." (Abu Muhammad al-Jariri)

• "Sufism is that at each moment the servant should be in accord with what is most appropriate (awla) at that moment." ('Amr ibn 'Uthman al-Makki)

Citations

[edit]- ^

- "Refworld | Iran: Information on Sufism or Tasawwuf (Islamic mysticism) in Iran". Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 1 January 1991. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021.

- Cook, David (May 2015). "Mysticism in Sufi Islam". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.51. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Anjum, Tanvir (2006). "Sufism in History and its Relationship with Power". Islamic Studies. 45 (2): 221–268. doi:10.52541/isiri.v45i2.4632. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20839016.

- Sebottendorff, Baron Rudolf von (2013-01-17). Secret Practices of the Sufi Freemasons: The Islamic Teachings at the Heart of Alchemy. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62055-001-4.

- Belhaj, Abdessamad (2013). "Legal Knowledge by Application: Sufism as Islamic Legal Hermeneutics in the 10th/12th Centuries". Studia Islamica. 108 (1): 82–107. doi:10.1163/19585705-12341276. ISSN 0585-5292. JSTOR 43577536.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Massington, L.; Radtke, B.; Chittick, W. C.; Jong, F. de.; Lewisohn, L.; Zarcone, Th.; Ernst, C.; Aubin, Françoise; Hunwick, J. O. (2012) [2000]. "Taṣawwuf". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 10. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1188. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- ^ a b Tariqa. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2014-02-04. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Hossein., Nasr, Seyyed (2008). The garden of truth : the vision and promise of Sufism, Islam's mystical tradition. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-162599-2. OCLC 191932004.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Back to Basics | Tazkiyah: An Introduction to Spiritually Blossoming This Islamic New Year". Amaliah. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ a b Abul Hasan ash-Shadhili (1993). The School of the Shadhdhuliyyah. Islamic Texts Society. ISBN 978-0-946621-57-6.

- ^ a b c Schimmel, Annemarie. "Sufism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-06-26.

Opposed to the dry casuistry of the lawyer-divines, the mystics nevertheless scrupulously observed the commands of the divine law. [...] the mystics belonged to all schools of Islamic law and theology of the times.

- ^ a b Bos, Matthijs van den (2002). Mystic regimes : Sufism and the state in Iran, from the late Qajar era to the Islamic Republic. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 1-4175-0678-4. OCLC 55505825.