Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Iraq War

View on Wikipedia

| Iraq War حرب العراق (Arabic) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the post–Cold War era, the Iraqi conflict and the war on terror | |||||||

Iraqi National Guard troops, 2004; toppling of Saddam Hussein's statue in Baghdad, 2003; destroyed Iraqi Type 69 tank, 2003; U.S soldier during a leaflet drop from a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter, 2008; British armored vehicles on patrol in Basra, 2008; destroyed headquarters of the Ba'ath Party in Baghdad, 2003 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Invasion (2003) Coalition of the willing |

Invasion (2003) | ||||||

|

After invasion (2003–11) |

After invasion (2003–11) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Coalition forces (2003)

≈103,000 (2008)[9] ≈400,000 (Kurdish Border Guard: 30,000,[10] Peshmerga: 75,000) |

≈70,000 (2007)[11] ≈60,000 (2007)[12][13] ≈1,000 (2008) ≈500–1,000 (2007) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Iraqi Security Forces (post-Saddam) Total wounded: 117,961 |

Iraqi combatant dead (invasion period): 7,600–45,000[67][68] Total dead: 34,144+–71,544+ Total captured: 120,000+ | ||||||

|

| |||||||

|

* "injured, diseased, or other medical": required medical air transport. UK number includes "aeromed evacuations". ** Total excess deaths include all additional deaths due to increased lawlessness, degraded infrastructure, poorer healthcare, etc. *** Violent deaths only – does not include excess deaths due to increased lawlessness, poorer healthcare, etc. **** Sukkariyeh, Syria was also affected (2008 Abu Kamal raid). | |||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ba'athism |

|---|

The Iraq War (Arabic: حرب العراق, romanized: ḥarb al-ʿirāq), also referred to as the Second Gulf War,[83][84] was a prolonged conflict in Iraq from 2003 to 2011. It began with the invasion by a United States-led coalition, which resulted in the overthrow of the Ba'athist government of Saddam Hussein. The conflict persisted as an insurgency that arose against coalition forces and the newly established Iraqi government. US forces were officially withdrawn in 2011. In 2014, the US became re-engaged in Iraq, leading a new coalition under Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve, as the conflict evolved into the ongoing Islamic State insurgency.

The Iraq invasion was part of the Bush administration's broader war on terror, launched in response to the September 11 attacks. In October 2002, the US Congress passed a resolution granting Bush authority to use military force against Iraq. The war began on March 20, 2003, when the US, joined by the UK, Australia, and Poland, initiated a "shock and awe" bombing campaign. Coalition forces launched a ground invasion, defeating Iraqi forces and toppling the Ba'athist regime. Saddam Hussein was captured in 2003 and executed in 2006.

The fall of Saddam's regime created a power vacuum, which, along with the Coalition Provisional Authority's mismanagement, fueled a sectarian civil war between Iraq's Shia majority and Sunni minority, and contributed to a lengthy insurgency. In response, the US deployed an additional 170,000 troops during the 2007 troop surge, which helped stabilize parts of the country. In 2008, Bush agreed to withdraw US combat troops, a process completed in 2011 under President Barack Obama.

The primary rationale for the invasion centered around false claims that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and that Saddam Hussein was supporting al-Qaeda. The 9/11 Commission concluded in 2004 that there was no credible evidence linking Saddam to al-Qaeda, and no WMD stockpiles were found in Iraq. These false claims faced widespread criticism, in the US and abroad. Kofi Annan, then secretary-general of the United Nations, declared the invasion illegal under international law, as it violated the UN Charter. The 2016 Chilcot Report, a British inquiry, concluded the war was unnecessary, as peaceful alternatives had not been fully explored. Iraq held multi-party elections in 2005, and Nouri al-Maliki became Prime Minister in 2006, a position he held until 2014. His government's policies alienated Iraq's Sunni minority, exacerbating sectarian tensions.

The war led to an estimated 150,000 to over a million deaths, including over 100,000 civilians, with most occurring during the post-invasion insurgency and civil war. The war had lasting geopolitical effects, including the emergence of the extremist Islamic State, whose rise led to the 2013–17 War in Iraq. The war damaged the US' international reputation, and Bush's popularity declined. UK prime minister Tony Blair's support for the war diminished his standing, contributing to his resignation in 2007.

Background

[edit]Following the Gulf War, the United Nations passed 16 Security Council resolutions calling for the complete elimination of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. Iraqi officials harassed inspectors and obstructed their work,[85] and in August 1998, the Iraqi government suspended cooperation with the inspectors completely, alleging that the inspectors were spying for the US.[86] The spying allegations were later substantiated.[87]

In October 1998, removing the Iraqi government became official US foreign policy with the enactment of the Iraq Liberation Act. The act provided $97 million for Iraqi "democratic opposition organizations" to "establish a program to support a transition to democracy in Iraq."[88] This legislation contrasted with the terms set out in United Nations Security Council Resolution 687, which focused on weapons and weapons programs and made no mention of regime change.[89]

One month after the passage of the Iraq Liberation Act, the US and UK launched a bombardment campaign of Iraq called Operation Desert Fox. The campaign's express rationale was to hamper Saddam Hussein's government's ability to produce chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, but US intelligence personnel also hoped it would help weaken Saddam's grip on power.[90]

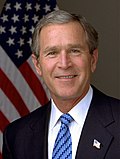

Following the 2000 presidential election of George W. Bush, the US moved towards a more aggressive Iraq policy. The Republican Party's campaign platform in the 2000 election called for "full implementation" of the Iraq Liberation Act as "a starting point" in a plan to "remove" Saddam.[91] Little formal movement towards an invasion occurred until the September 11 attacks, although plans were drafted and meetings were held from the first days of his administration.[92][93]

Pre-war events

[edit]

Following the September 11 attacks, the Bush administration's national security team debated an Iraq invasion. On the day of the attacks, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld asked his aides for "best info fast. Judge whether good enough hit Saddam Hussein at the same time. Not only Osama bin Laden."[95] The next day, Bush ordered White House counterterrorism coordinator Richard A. Clarke to investigate possible Iraqi involvement in the September 11 attacks, believing that a devastating attack like 9/11 involved a state sponsor.[96]

Bush spoke with Rumsfeld on 21 November and instructed him to conduct a confidential review of OPLAN 1003, the war plan for invading Iraq.[97][98] Rumsfeld met with General Tommy Franks, the commander of US Central Command, on 27 November to go over the plans. A record of the meeting includes the question "How start?", listing multiple possible justifications for a US–Iraq War.[94][99] Bush began laying the public groundwork for an invasion of Iraq in his January 2002 State of the Union address, calling Iraq a member of the Axis of Evil, and saying that the US "will not permit the world's most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world's most destructive weapons."[100]

The intelligence community, however, indicated that there was no evidence linking Saddam Hussein to the September 11 attacks and there was little evidence that Iraq had any collaborative ties with Al Qaeda.[101][102]: 334 Ultimately, the rationale for invading Iraq as a response to 9/11 has been widely refuted, as there was no cooperation between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda.[103][104][105][106][107][108][109]

A 5 September 2002 report from Major General Glen Shaffer revealed that the Joint Chiefs of Staff's J2 Intelligence Directorate had concluded that the United States' knowledge on different aspects of Iraq's WMD program ranged from essentially zero to ~75%, and that knowledge was weak on aspects of a possible nuclear weapons program. "Our knowledge of the Iraqi nuclear weapons program is based largely… on analysis of imprecise intelligence," they concluded. "Our assessments rely heavily on analytic assumptions and judgment rather than hard evidence."[110][111] Similarly, the British government found no evidence that Iraq possessed nuclear weapons or any other weapons of mass destruction and that Iraq posed no threat to the West, a conclusion British diplomats shared with the US government.[112] The US intelligence community was of the opinion that Iraq had no nuclear weapons, and had no information about whether Iraq had biological weapons.[113][114][115][116]

Vice President Dick Cheney and Defense Secretary Rumsfeld expressed skepticism toward the CIA's intelligence and accuracy to predict threats, and instead preferred outside analysis with intelligence supplied by the Iraqi National Congress, which alleged that Saddam was pursuing WMD development and had ties to al-Qaeda.[96] Bush began formally making his case to the international community for an invasion of Iraq in his 12 September 2002 address to the UN Security Council.[117]

In October 2002, the US Congress passed the Iraq Resolution.[118] Key US allies in NATO, such as the United Kingdom, agreed with the US actions, while France and Germany were critical of plans to invade Iraq, arguing instead for continued diplomacy and weapons inspections. After considerable debate, the UN Security Council adopted a compromise resolution, UN Security Council Resolution 1441, which authorized the resumption of weapons inspections and promised "serious consequences" for non-compliance. Security Council members France and Russia made clear that they did not consider these consequences to include the use of force to overthrow the Iraqi government.[119] The US and UK ambassadors to the UN publicly confirmed this reading of the resolution.[120]

Resolution 1441 set up inspections by the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the International Atomic Energy Agency. Saddam accepted the resolution on 13 November and inspectors returned to Iraq under the direction of UNMOVIC chairman Hans Blix and IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei. As of February 2003, the IAEA "found no evidence or plausible indication of the revival of a nuclear weapons program in Iraq"; the IAEA concluded that certain items which could have been used in nuclear enrichment centrifuges, such as aluminum tubes, were in fact intended for other uses.[121] In March 2003, Blix said progress had been made in inspections, and no evidence of WMD had been found.[122]

On 5 February 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell appeared before the UN to present evidence that Iraq was hiding unconventional weapons. Despite warnings from the German Federal Intelligence Service and the British Secret Intelligence Service that the source was untrustworthy, Powell's presentation included information based on the claims of Rafid Ahmed Alwan al-Janabi, codenamed "Curveball", an Iraqi emigrant living in Germany who later admitted that his claims had been false.[123] Besides claiming a relationship between al-Qaeda and Iraq, Powell also alleged that al-Qaeda was attempting to acquire weapons of mass destruction from Iraq.[124]

As a follow-up to Powell's presentation, the United States, the United Kingdom, Poland, Italy, Australia, Denmark, Japan, and Spain proposed a resolution authorizing the use of force in Iraq, but NATO members like Canada, France, and Germany, together with Russia, strongly urged continued diplomacy. Facing a losing vote as well as a likely veto from France and Russia, the US, the UK, Poland, Spain, Denmark, Italy, Japan, and Australia eventually withdrew their resolution.[125][126]

In March 2003, the United States, the UK, Poland, Australia, Spain, Denmark, and Italy began preparing for the invasion of Iraq with a host of public relations and military moves. In an address to the nation on 17 March 2003, Bush demanded that Saddam and his two sons, Uday and Qusay, surrender and leave Iraq, giving them a 48-hour deadline.[127]

The UK House of Commons held a debate on going to war on 18 March 2003 where the government motion was approved 412 to 149.[128] The vote was a key moment in the history of the Blair government, as the number of government MPs who rebelled against the vote was the greatest since the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. Three government ministers resigned in protest at the war, John Denham, Lord Hunt of Kings Heath, and the then Leader of the House of Commons Robin Cook.

Opposition to invasion

[edit]In October 2002, former US President Bill Clinton warned about the possible dangers of pre-emptive military action against Iraq. Speaking in the UK at a Labour Party conference he said: "As a preemptive action today, however well-justified, may come back with unwelcome consequences in the future... I don't care how precise your bombs and your weapons are when you set them off, innocent people will die."[129][130] Of 209 House Democrats in Congress, 126 voted against the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, although 29 of 50 Democrats in the Senate voted in favor. Only one Republican Senator, Lincoln Chafee, voted against. The Senate's lone Independent, Jim Jeffords, voted against. Retired US Marine, former Navy Secretary and future US senator Jim Webb wrote shortly before the vote, "Those who are pushing for a unilateral war in Iraq know full well that there is no exit strategy if we invade."[131] Pope John Paul II also publicly condemned the military intervention, as well as saying directly to Bush privately: "Mr. President, you know my opinion about the war in Iraq... Every violence, against one or a million, is a blasphemy addressed to the image and likeness of God."[132]

On 20 January 2003, French Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin declared "we believe that military intervention would be the worst solution".[134] Meanwhile, anti-war groups across the world organized public protests. According to French academic Dominique Reynié, between 3 January and 12 April 2003, 36 million people globally took part in almost 3,000 protests against the war in Iraq, with demonstrations on 15 February 2003 being the largest.[135] Nelson Mandela voiced his opposition in late January, stating "All that (Mr. Bush) wants is Iraqi oil," and questioning if Bush deliberately undermined the U.N. "because the secretary-general of the United Nations [was] a black man".[136]

In February 2003, the US Army's top general, Eric Shinseki, told the Senate Armed Services Committee that it would take "several hundred thousand soldiers" to secure Iraq.[137] Two days later, US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said the post-war troop commitment would be less than the number of troops required to win the war, and that "the idea that it would take several hundred thousand US forces is far from the mark." Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz said Shinseki's estimate was "way off the mark," because other countries would take part in an occupying force.[138]

Germany's Foreign Secretary Joschka Fischer, although having been in favor of stationing German troops in Afghanistan, advised Federal Chancellor Schröder not to join the war in Iraq. Fischer famously confronted United States Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld at the 39th Munich Security Conference in 2003 on the secretary's purported evidence for Iraq's possession of weapons of mass destruction: "Excuse me, I am not convinced!"[139] Fischer also cautioned the United States against assuming that democracy would easily take root post-invasion; "You're going to have to occupy Iraq for years and years, the idea that democracy will suddenly blossom is something that I can't share. … Are Americans ready for this?"[140]

In July 2003, former US ambassador Joseph C. Wilson published an op-ed challenging the Bush administration's claim that Iraq sought uranium from Niger, a key justification for the war. In apparent retaliation, officials leaked the identity of Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, an undercover CIA officer, exposing her covert status. The resulting investigation led to the conviction of Lewis "Scooter" Libby, Vice President Cheney's chief of staff, for perjury and obstruction of justice, and his sentence was commuted by President Bush.[141]

There were serious legal questions surrounding the launching of the war against Iraq and the Bush Doctrine of preemptive war in general. On 16 September 2004, Kofi Annan, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, said of the invasion "...was not in conformity with the UN Charter. From our point of view, from the Charter point of view, it was illegal."[142]

Course of the war

[edit]2003 - Invasion

[edit]

The first CIA team entered Iraq on 10 July 2002.[143] This team was composed of members of the CIA's Special Activities Division and was later joined by members of the US military's elite Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).[144] Together, they prepared for an invasion by conventional forces. These efforts consisted of persuading the commanders of several Iraqi military divisions to surrender rather than oppose the invasion, and identifying all the initial leadership targets during very high risk reconnaissance missions.[144]

Most importantly, their efforts organized the Kurdish Peshmerga to become the northern front of the invasion. Together this force defeated Ansar al-Islam in Iraqi Kurdistan before the invasion and then defeated the Iraqi army in the north.[144][145] The battle against Ansar al-Islam, known as Operation Viking Hammer, led to the death of a substantial number of militants and the uncovering of a chemical weapons facility at Sargat.[143][146]

At 5:34 am Baghdad time on 20 March 2003[147] (9:34 pm, 19 March EST) the surprise[148] military invasion of Iraq began. There was no declaration of war.[149] The 2003 invasion of Iraq was led by US Army General Tommy Franks, under the code-name Operation Iraqi Freedom,[150] the UK code-name Operation Telic, and the Australian code-name Operation Falconer. Coalition forces also cooperated with Kurdish Peshmerga forces in the north. Approximately forty other governments, the "Coalition of the Willing", participated by providing troops, equipment, services, security, and special forces, with 248,000 soldiers from the United States, 45,000 British soldiers, 2,000 Australian soldiers and 194 Polish soldiers from Special Forces unit GROM sent to Kuwait for the invasion.[151] The invasion force was also supported by Iraqi Kurdish militia troops, estimated to number upwards of 70,000.[152]

According to General Franks, there were eight objectives of the invasion:

"First, ending the regime of Saddam Hussein. Second, to identify, isolate, and eliminate Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. Third, to search for, to capture, and to drive out terrorists from that country. Fourth, to collect such intelligence as we can relate to terrorist networks. Fifth, to collect such intelligence as we can relate to the global network of illicit weapons of mass destruction. Sixth, to end sanctions and to immediately deliver humanitarian support to the displaced and to many needy Iraqi citizens. Seventh, to secure Iraq's oil fields and resources, which belong to the Iraqi people. And last, to help the Iraqi people create conditions for a transition to representative self-government."[153]

The invasion was a quick and decisive operation encountering major resistance, though not what the US, British and other forces expected. The Iraqi regime had prepared to fight both a conventional and irregular, asymmetric warfare at the same time, conceding territory when faced with superior conventional forces, largely armored, but launching smaller-scale attacks in the rear using fighters dressed in civilian and paramilitary clothes.

Coalition troops launched air and amphibious assaults on the al-Faw Peninsula to secure the oil fields there and the important ports, supported by warships of the Royal Navy, Polish Navy, and Royal Australian Navy. The United States Marine Corps' 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit, attached to 3 Commando Brigade and the Polish Special Forces unit GROM, attacked the port of Umm Qasr, while the British Army's 16 Air Assault Brigade secured the oil fields in southern Iraq.[154][155]

The US 3rd Infantry Division moved westward and then northward through the western desert toward Baghdad, while the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force moved more easterly along Highway 1 through the center of the country, and 1 (UK) Armoured Division moved northward through the eastern marshland.[156] The American 1st Marine Division fought through Nasiriyah in a battle to seize the major road junction.[157] The US 3rd Infantry Division defeated Iraqi forces entrenched in and around Talil Airfield.[158]

With the Nasiriyah and Talil Airfields secured in its rear, the 3rd Infantry Division supported by the 101st Airborne Division continued its attack north toward Najaf and Karbala, but a severe sand storm slowed the coalition advance and there was a halt to consolidate and make sure the supply lines were secure.[159] When they started again they secured the Karbala Gap, a key approach to Baghdad, then secured the bridges over the Euphrates River, and US Army forces poured through the gap on to Baghdad. In the middle of Iraq, the 1st Marine Division fought its way to the eastern side of Baghdad and prepared for the attack to seize the city.[160]

On 9 April, Baghdad fell, ending Saddam's 24‑year rule. US forces seized the deserted Ba'ath Party ministries and, according to some reports later disputed by the Marines on the ground, stage-managed[161] the tearing down of a huge iron statue of Saddam. Allegedly, though not seen in the photos or heard on the videos, shot with a zoom lens, was the chant of the inflamed crowd for Muqtada al-Sadr, the radical Shiite cleric.[162] The abrupt fall of Baghdad was accompanied by gratitude toward the invaders, but also civil disorder, including the looting of public and government buildings and increased crime.[163][164]

According to the Pentagon, 250,000 short tons (230,000 t) (of 650,000 short tons (590,000 t) total) of ordnance was looted, providing a significant source of ammunition for the Iraqi insurgency. The invasion phase concluded when Tikrit, Saddam's home town, fell with little resistance to the US Marines of Task Force Tripoli on 15 April.

In the invasion phase of the war (19 March – 30 April), an estimated 9,200 Iraqi combatants were killed by coalition forces along with an estimated 3,750 non-combatants, i.e. civilians who did not take up arms.[165] Coalition forces reported the death in combat of 139 US military personnel[166] and 33 UK military personnel.[167]

Post-invasion phase

[edit]2003: Beginnings of insurgency

[edit]

Widespread looting and low-level criminal activity gripped the country in April 2003. By that point it was clear that there were not enough US forces to control the breakdown of order and little plan to restore it.[168][169]

On 1 May 2003, President Bush visited the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln operating a few miles west of San Diego, California and declared an end to major combat operations in Iraq. At sunset, he held his nationally televised "Mission Accomplished" speech, delivered before the sailors and airmen on the flight deck.[98] Ambassador Paul Bremer arrived in Iraq on May 12, 2003 and established the Coalition Provisional Authority. One of his first actions was to initiate the debaathification process.[168]

Nevertheless, Saddam Hussein remained at large, and significant pockets of resistance remained. After Bush's speech, coalition forces noticed a flurry of attacks on its troops began to gradually increase in various regions, such as the "Sunni Triangle".[170][171] Muqtada al-Sadr, the leader of a large anti-American faction in Baghdad's Sadr City, issued a fatwa allowing his followers to partake in the looting provided a portion of their takings were gifted to the Sadrist Movement.[169]

Coalition Provisional Authority and the Iraq Survey Group

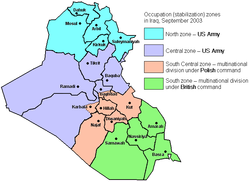

[edit]Shortly after the invasion, the multinational coalition created the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA; Arabic: سلطة الائتلاف الموحدة), based in the Green Zone, as a transitional government of Iraq until the establishment of a democratic government. Citing United Nations Security Council Resolution 1483 and the laws of war, the CPA vested itself with executive, legislative, and judicial authority over the Iraqi government from the period of the CPA's inception on 21 April 2003 until its dissolution on 28 June 2004.

The CPA was originally headed by Jay Garner, a former US military officer, but his appointment lasted only until 11 May 2003, when President Bush appointed L. Paul Bremer. On 16 May 2003, his first day on the job, Paul Bremer issued Coalition Provisional Authority Order 1 to exclude from the new Iraqi government and administration members of the Baathist party. This policy, known as De-Ba'athification, eventually led to the removal of 85,000 to 100,000 Iraqi people from their jobs,[172] including 40,000 school teachers who had joined the Baath Party simply to stay employed. US army general Ricardo Sanchez called the decision a "catastrophic failure".[173] Bremer served until the CPA's dissolution in June 2004.

In May 2003, the US Advisor to Iraq Ministry of Defense within the CPA, Walter B. Slocombe, advocated changing the pre-war Bush policy to employ the former Iraq Army after hostilities on the ground ceased.[174] At the time, hundreds of thousands of former Iraq soldiers who had not been paid for months were waiting for the CPA to hire them back to work to help secure and rebuild Iraq. Despite advice from US Military Staff working within the CPA, Bremer met with President Bush, via video conference, and asked for authority to change the US policy. Bush gave Bremer and Slocombe authority to change the pre-war policy. Slocombe announced the policy change in Spring 2003. The decision led to the alienation of hundreds of thousands of former armed Iraq soldiers, who subsequently aligned themselves with various occupation resistance movements all over Iraq. In the week before the order to dissolve the Iraq Army, no coalition forces were killed by hostile action in Iraq; the week after, five US soldiers were killed. Then, on 18 June 2003, coalition forces opened fire on former Iraq soldiers protesting in Baghdad who were throwing rocks at coalition forces. The policy to disband the Iraq Army was reversed by the CPA only days after it was implemented. But it was too late; the former Iraq Army shifted their alliance from one that was ready and willing to work with the CPA to one of armed resistance against the CPA and the coalition forces.[175]

Another group created by the multinational force in Iraq post-invasion was the 1,400-member international Iraq Survey Group, who conducted a fact-finding mission to find Iraq's weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs. In 2004, the ISG's Duelfer Report stated that Iraq did not have a viable WMD program.[176][177][178][179][180][181]

Ramadan Offensive 2003

[edit]Coalition military forces launched several operations around the Tigris River peninsula and in the Sunni Triangle. A series of similar operations were launched throughout the summer in the Sunni Triangle. In late 2003, the intensity and pace of insurgent attacks increased. A surge in guerrilla attacks ushered in an insurgent effort that was termed the "Ramadan Offensive".

Fall 2003 saw major attacks at the Jordanian Embassy and the bombing of UN Headquarters in Baghdad in which Sérgio Vieira de Mello was killed.[168] The three governorates with the highest number of attacks were Baghdad, Al Anbar, and Saladin. Those three governorates account for 35% of the population, but by December 2006 they were responsible for 73% of US military deaths and an even higher percentage of recent US military deaths (about 80%).[182]

To counter this offensive, coalition forces began to use air power and artillery again for the first time since the end of the invasion, by striking suspected ambush sites and mortar launching positions. Surveillance of major routes, patrols, and raids on suspected insurgents was stepped up. In addition, two villages, including Saddam's birthplace of al-Auja and the small town of Abu Hishma, were surrounded by barbed wire and monitored.

Capturing former government leaders

[edit]

In summer 2003, the multinational forces focused on capturing the remaining leaders of the former government. On 22 July, a raid by the US 101st Airborne Division and soldiers from Task Force 20 killed Saddam's sons (Uday and Qusay) along with one of his grandsons. In all, over 300 top leaders of the former government were killed or captured, as well as numerous lesser functionaries and military personnel.

Saddam Hussein was captured on 13 December 2003, on a farm near Tikrit in Operation Red Dawn.[183] The operation was conducted by the US 4th Infantry Division and members of Task Force 121. Intelligence on Saddam's whereabouts came from his family members and former bodyguards.[184]

With the capture of Saddam and a drop in the number of insurgent attacks, some concluded that multinational forces were prevailing in the fight against the insurgency. The provisional government began training the new Iraqi security forces intended to police the country, and the US promised over $20 billion in reconstruction money in the form of a credit against Iraq's future oil revenues. Oil revenue was also used for rebuilding schools and for work on the electrical and refining infrastructure.

Shortly after Saddam's capture, elements left out of the Coalition Provisional Authority began to agitate for elections and the formation of an Iraqi Interim Government. Most prominent among these was the Shia cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. The Coalition Provisional Authority opposed allowing democratic elections at this time.[185] The insurgents stepped up their activities. The two most turbulent centers were the area around Fallujah and the poor Shia sections of cities from Baghdad (Sadr City) to Basra in the south.

Looting of artifacts from Iraqi museums

[edit]Following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, large numbers of antiquities including the Gilgamesh Dream Tablet were stolen, both from museums, such as the Iraq National Museum, but also because of illegal excavations at archeological sites throughout the country. Many of them were smuggled into the United States through the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Israel, contrary to federal law. Donald Rumsfeld rejected the claim that they were removed by US military personnel. In the 2020s, about 17,000 artifacts were returned to Iraq from the US and Middle Eastern countries. But according to an Iraqi archeology professor at the University of Baghdad, the repatriation of these items was only a partial success; the Baghdad office of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) continues to search for the loot worldwide. Many Iraqis blame the United States for the loss of so many pieces of their country's history.[186][187]

2004: Insurgency expands

[edit]

The start of 2004 was marked by a relative lull in violence. Violence increased during the Iraq Spring Fighting of 2004 with foreign fighters from around the Middle East as well as Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, an al-Qaeda-linked group led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, helping to drive the insurgency.[188] As the violence intensified in March, there was a change in targeting from the coalition forces towards the new Iraqi Security Forces, as hundreds of Iraqi civilians and police were killed over the next few months in a series of bombings. In the bloodiest day of the war since the start, hundreds of Shi'a were killed when five bombs exploded on March 2 during Ashoura celebrations.[168]

The most serious fighting of the war so far began on 31 March 2004, when Iraqi insurgents in Fallujah ambushed a Blackwater USA convoy led by four US private military contractors who were providing security for food caterers Eurest Support Services.[189] The four armed contractors, Scott Helvenston, Jerko Zovko, Wesley Batalona, and Michael Teague, were killed with grenades and small arms fire. Their bodies were dragged from their vehicles by locals, beaten, burned and their mutilated corpses hung over a bridge crossing the Euphrates.[190] Photos of the event were released to news agencies worldwide, causing indignation and moral outrage in the United States, and prompting an unsuccessful "pacification" of the city: the First Battle of Fallujah in April 2004.

Followers of the Shi'a mullah Muqtada al-Sadr known as the Mahdi militia paraded through multiple cities. In April 2004, the Shi'a demonstrators launched attacks on coalition targets in an attempt to seize control from Iraqi security forces. Southern and central Iraq began to erupt in urban guerrilla combat as multinational forces attempted to keep control and prepared for a counteroffensive. Several coalition troops died in Sadr City and Najaf. These clashes lasted until June 2004.[168]

In June 2004, the CPA formally transferred sovereignty to the Iraqi government, headed by interim Prime Minister Ayad Allawi.[168] Allawi opposed the hasty de-baathification that would destabilize the political structure of the Iraqi government.[169] His secular rule of law agenda was unsuccessful as "instritutionalized sectarianism" developed in the escalating conflict with Muqtada al-Sadr in Najaf and Sunni radicals in Fallujah.[191]

In one of the most significant single attacks of the war 49 newly trained Iraqi soldiers were executed by insurgents wearing police uniforms on 23 October 2004. Analysts note this supports the view that Iraqi police forces and Interior Ministry had been compromised by insurgents. Allawi blamed the attack on coalition forces.[168]

The offensive in Fallujah resumed in November 2004 in the bloodiest battle of the war: the Second Battle of Fallujah, described by the US military as "the heaviest urban combat (that they had been involved in) since the Battle of Hue City in Vietnam."[192] During the assault, US forces used white phosphorus as an incendiary weapon against insurgent personnel, attracting controversy. The 46‑day battle resulted in a victory for the coalition, with 95 US soldiers killed and approximately 1,350 insurgents. Fallujah was totally devastated during the fighting, though civilian casualties were low, as they had mostly fled before the battle.[193]

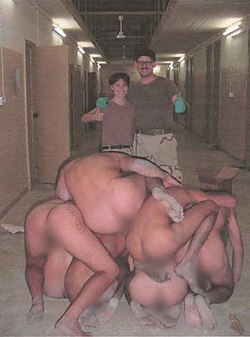

Another major event of that year was the revelation of widespread prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib, which received international media attention in April 2004. First reports of the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse, as well as graphic pictures showing US military personnel taunting and abusing Iraqi prisoners, came to public attention from a 60 Minutes II news report and a Seymour M. Hersh article in The New Yorker (posted online on 30 April).[194] Military correspondent Thomas Ricks claimed that these revelations dealt a blow to the moral justifications for the occupation in the eyes of many people, especially Iraqis, and was a turning point in the war.[195]

2004 also marked the beginning of Military Transition Teams in Iraq, which were teams of US military advisors assigned directly to New Iraqi Army units.

2005: Elections and transitional government

[edit]

On 31 January, Iraqis elected the Iraqi Transitional Government to draft a permanent constitution. Although some violence and a widespread Sunni boycott marred the event, most of the eligible Kurd and Shia populace participated. On 4 February, Paul Wolfowitz announced that 15,000 US troops whose tours of duty had been extended in order to provide election security would be pulled out of Iraq by the next month.[196] February to April were relatively peaceful compared to the carnage of November and January, with insurgent attacks averaging 30 a day from the prior average of 70.

The Battle of Abu Ghraib on 2 April 2005 was an attack on US forces at Abu Ghraib prison, which consisted of heavy mortar and rocket fire, under which an estimated 80–120 armed insurgents attacked with grenades, small arms, and two vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED). The US force's munitions ran so low that orders to fix bayonets were given in preparation for hand-to-hand fighting. It was considered to be the largest coordinated assault on a US base since the Vietnam War.[197]

Hopes for a quick end to the insurgency and a withdrawal of US troops were dashed in May, Iraq's bloodiest month since the invasion. Suicide bombers, believed to be mainly disheartened Iraqi Sunni Arabs, Syrians and Saudis, tore through Iraq. Their targets were often Shia gatherings or civilian concentrations of Shias. As a result, over 700 Iraqi civilians died in that month, as well as 79 US soldiers.

Summer 2005 saw fighting around Baghdad and at Tall Afar in northwestern Iraq as US forces tried to seal off the Syrian border. This led to fighting in the autumn in the small towns of the Euphrates valley between the capital and that border.[198]

A referendum was held on 15 October in which the new Iraqi constitution was ratified. An Iraqi National Assembly was elected in December, with participation from the Sunnis as well as the Kurds and Shia.[198]

Insurgent attacks increased in 2005 with 34,131 recorded incidents, compared to a total 26,496 for the previous year.[199]

2006: Civil war and permanent Iraqi government

[edit]

The beginning of 2006 was marked by government creation talks, growing sectarian violence, and continuous anti-coalition attacks. Sectarian violence expanded to a new level of intensity following the al-Askari Mosque bombing in the Iraqi city of Samarra, on 22 February 2006. The explosion at the mosque, one of the holiest sites in Shi'a Islam, is believed to have been caused by a bomb planted by al-Qaeda.

Although no injuries occurred in the blast, the mosque was severely damaged and the bombing resulted in violence over the following days. Over 100 dead bodies with bullet holes were found on 23 February, and at least 165 people are thought to have been killed. In the aftermath of this attack, the US military calculated that the average homicide rate in Baghdad tripled from 11 to 33 deaths per day. In 2006 the UN described the environment in Iraq as a "civil war-like situation".[200]

On 12 March, five United States Army soldiers of the 502nd Infantry Regiment raped the 14-year-old Iraqi girl Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi, and then murdered her, her father, her mother Fakhriya Taha Muhasen, and her six-year-old sister Hadeel Qassim Hamza al-Janabi. The soldiers then set fire to the girl's body to conceal evidence of the crime.[201] Four of the soldiers were convicted of rape and murder and the fifth was convicted of lesser crimes for their involvement in the events, which became known as the Mahmudiyah rape and killings.[202][203]

On 6 June 2006, the US successfully tracked Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq who was killed in a targeted killing, while attending a meeting in an isolated safehouse approximately 8 km (5.0 mi) north of Baqubah. Having been tracked by a British UAV, radio contact was made between the controller and two US Air Force F-16C jets, which identified the house and at 14:15 GMT, the lead jet dropped two 500‑pound (230 kg) guided bombs, a laser-guided GBU‑12 and GPS-guided GBU‑38 on the building where he was located. Six others – three male and three female individuals – were also reported killed. Among those killed were one of his wives and their child.

The government of Iraq took office on 20 May 2006, following approval by the members of the Iraqi National Assembly. This followed the general election in December 2005. The government succeeded the Iraqi Transitional Government, which had continued in office in a caretaker capacity until the formation of the permanent government.

Iraq Study Group report and Saddam's execution

[edit]The Iraq Study Group Report was released on 6 December 2006. The Iraq Study Group made up of people from both of the major US parties, was led by co-chairs James Baker, a former Secretary of State (Republican), and Lee H. Hamilton, a former US Representative (Democrat). It concluded that "the situation in Iraq is grave and deteriorating" and "US forces seem to be caught in a mission that has no foreseeable end." The report's 79 recommendations include increasing diplomatic measures with Iran and Syria and intensifying efforts to train Iraqi troops. On 18 December, a Pentagon report found that insurgent attacks were averaging about 960 attacks per week, the highest since the reports had begun in 2005.[204]

Coalition forces formally transferred control of a governorate to the Iraqi government. Military prosecutors charged eight US Marines with the murders of 24 Iraqi civilians in Haditha in November 2005, 10 of them women and children. Four officers were also charged with dereliction of duty in relation to the event.[205]

Saddam Hussein was hanged on 30 December 2006, after being found guilty of crimes against humanity by an Iraqi court after a year-long trial.[206]

2007: US troops surge

[edit]

On 10 January 2007, in a televised address to the US public, Bush proposed 21,500 more troops for Iraq, a job program for Iraqis, more reconstruction proposals, and $1.2 billion for these programs.[207] On 23 January 2007, in the 2007 State of the Union Address, Bush announced he was "deploying reinforcements of more than 20,000 additional soldiers and Marines to Iraq". On 10 February 2007, David Petraeus was made commander of Multi-National Force – Iraq (MNF-I), the four-star post that oversees all coalition forces in the country, replacing General George Casey. In his new position, Petraeus oversaw all coalition forces in Iraq and employed them in the new "Surge" strategy outlined by the Bush administration.[208][209]

On 10 May 2007, 144 Iraqi Parliamentary lawmakers signed onto a legislative petition calling on the US to set a timetable for withdrawal.[210] On 3 June 2007, the Iraqi Parliament voted 85 to 59 to require the Iraqi government to consult with Parliament before requesting additional extensions of the UN Security Council Mandate for coalition operations in Iraq.[211]

Pressures on US troops were compounded by continued withdrawal of coalition forces.[212] In early 2007, British Prime Minister Blair announced that following Operation Sinbad, British troops would begin to withdraw from Basra Governorate, handing security over to the Iraqis.[212] In July Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen also announced the withdrawal of 441 Danish troops from Iraq, leaving only a unit of nine soldiers manning four observational helicopters.[213] In October 2019, the new Danish government said it would not re-open an official probe into the country's participation in the US-led military coalition in 2003 Iraqi war.[214]

Planned troop reduction

[edit]In a speech made to Congress on 10 September 2007, Petraeus "envisioned the withdrawal of roughly 30,000 US troops by next summer, beginning with a Marine contingent [in September]."[215] On 13 September, Bush announced a limited withdrawal of troops from Iraq.[216][217]

Bush said 5,700 personnel would be home by Christmas 2007, and expected thousands more to return by July 2008. The plan would take troop numbers back to their level before the surge at the beginning of 2007.

Effects of the surge on security

[edit]By March 2008, violence in Iraq was reportedly curtailed by 40–80%, according to a Pentagon report.[218] Independent reports[219][220] raised questions about those assessments. An Iraqi military spokesman claimed that civilian deaths since the start of the troop surge plan were 265 in Baghdad, down from 1,440 in the four previous weeks. The New York Times counted more than 450 Iraqi civilians killed during the same 28‑day period, based on initial daily reports from Iraqi Interior Ministry and hospital officials.

Historically, the daily counts tallied by The New York Times underestimated the total death toll by 50% or more when compared to studies by the UN, which rely upon figures from the Iraqi Health Ministry and morgue figures.[221]

The rate of US combat deaths in Baghdad nearly doubled to 3.14 per day in the first seven weeks of the "surge" in security activity, compared to the previous period. Across the rest of Iraq, it decreased slightly.[222][223]

On 14 August 2007, the deadliest single attack of the whole war occurred. Nearly 800 civilians were killed by a series of coordinated suicide bomb attacks on the northern Iraqi settlement of Kahtaniya. Over 100 homes and shops were destroyed in the blast. US officials blamed al‑Qaeda. The targeted villagers belonged to the non-Muslim Yazidi ethnic minority. The attack may have represented the latest in a feud that erupted earlier that year when members of the Yazidi community stoned to death a teenage girl called Du'a Khalil Aswad accused of dating a Sunni Arab man and converting to Islam. The killing of the girl was recorded on camera-mobiles and the video was uploaded onto the internet.[224][225][226][227]

On 13 September 2007, Abdul Sattar Abu Risha was killed in a bomb attack in the city of Ramadi.[228] He was an important US ally because he led the "Anbar Awakening", an alliance of Sunni Arab tribes that opposed al-Qaeda. The latter organization claimed responsibility for the attack.[229] A statement posted on the Internet by the shadowy Islamic State of Iraq called Abu Risha "one of the dogs of Bush" and described Thursday's killing as a "heroic operation that took over a month to prepare".[230]

There was a reported trend of decreasing US troop deaths after May 2007, and violence against coalition troops had fallen to the "lowest levels since the first year of the American invasion".[231] These, and several other positive developments, were attributed to the surge by many analysts.[232]

Data from the Pentagon and other US agencies such as the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that daily attacks against civilians in Iraq remained "about the same" since February. The GAO also stated that there was no discernible trend in sectarian violence.[233] This report ran counter to reports to Congress, which showed a general downward trend in civilian deaths and ethno-sectarian violence since December 2006.[234] By late 2007, as the US troop surge began to wind down, violence in Iraq had begun to decrease from its 2006 highs.[235]

Entire neighborhoods in Baghdad were ethnically cleansed by Shia and Sunni militias and sectarian violence broke out in every Iraqi city where there was a mixed population.[236][237][238] Investigative reporter Bob Woodward cited US government sources according to which the US "surge" was not the primary reason for the drop in violence in 2007–08. Instead, according to that view, the reduction of violence was due to newer covert techniques by US military and intelligence officials to find, target, and kill insurgents, including working closely with former insurgents.[239]

In the Shia region near Basra, British forces turned over security for the region to Iraqi Security Forces. Basra was the ninth governorate of Iraq's 18 governorates to be returned to local security forces' control since the beginning of the occupation.[240]

Political developments

[edit]Over half of the members of Iraq's parliament rejected the continuing occupation of their country for the first time. 144 of the 275 lawmakers signed onto a legislative petition that would require the Iraqi government to seek approval from Parliament before it requests an extension of the UN mandate for foreign forces to be in Iraq, which expires at the end of 2008. It also calls for a timetable for troop withdrawal and a freeze on the size of foreign forces. The UN Security Council mandate for US‑led forces in Iraq will terminate "if requested by the government of Iraq."[241] 59% of those polled in the US support a timetable for withdrawal.[242]

In mid-2007, the coalition began a controversial program to recruit Iraqi Sunnis (often former insurgents) for the formation of "Guardian" militias. These Guardian militias are intended to support and secure various Sunni neighborhoods against the Islamists.[243]

Tensions with Iran

[edit]In 2007, tensions increased greatly between Iran and Iraqi Kurdistan due to the latter's giving sanctuary to the militant Kurdish secessionist group Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan (PEJAK). According to reports, Iran had been shelling PEJAK positions in Iraqi Kurdistan since 16 August. These tensions further increased with a border incursion on 23 August by Iranian troops who attacked several Kurdish villages killing an unknown number of civilians and militants.[244]

Coalition forces also began to target alleged Iranian Quds force operatives in Iraq, either arresting or killing suspected members. The Bush administration and coalition leaders began to publicly state that Iran was supplying weapons, particularly EFP devices, to Iraqi insurgents and militias although to date have failed to provide any proof for these allegations. Further sanctions on Iranian organizations were also announced by the Bush administration in autumn 2007. On 21 November 2007, Lieutenant General James Dubik, who is in charge of training Iraqi security forces, praised Iran for its "contribution to the reduction of violence" in Iraq by upholding its pledge to stop the flow of weapons, explosives, and training of extremists in Iraq.[245]

Tensions with Turkey

[edit]Border incursions by PKK militants based in Northern Iraq have continued to harass Turkish forces, with casualties on both sides. In the fall of 2007, the Turkish military stated their right to cross the Iraqi Kurdistan border in "hot pursuit" of PKK militants and began shelling Kurdish areas in Iraq and attacking PKK bases in the Mount Cudi region with aircraft.[246][247] The Turkish parliament approved a resolution permitting the military to pursue the PKK in Iraqi Kurdistan.[248] In November, Turkish gunships attacked parts of northern Iraq in the first such attack by Turkish aircraft since the border tensions escalated.[249] Another series of attacks in mid-December hit PKK targets in the Qandil, Zap, Avashin and Hakurk regions. The latest series of attacks involved at least 50 aircraft and artillery and Kurdish officials reported one civilian killed and two wounded.[250]

Additionally, weapons that were given to Iraqi security forces by the US military were being recovered by authorities in Turkey after being used by PKK in that state.[251]

Blackwater private security controversy

[edit]On 17 September 2007, the Iraqi government announced that it was revoking the license of the US security firm Blackwater USA over the firm's involvement in the killing of eight civilians, including a woman and an infant,[252] in a firefight that followed a car bomb explosion near a State Department motorcade.

2008: Civil war continues

[edit]

Throughout 2008, US officials and independent think tanks began to point to improvements in the security situation, as measured by key statistics. According to the US Defense Department, in December 2008 the "overall level of violence" in the country had dropped 80% since before the surge began in January 2007, and the country's murder rate had dropped to prewar levels. They also pointed out that the casualty figure for US forces in 2008 was 314 against a figure of 904 in 2007.[253]

According to the Brookings Institution, Iraqi civilian fatalities numbered 490 in November 2008 as against 3,500 in January 2007, whereas attacks against the coalition numbered somewhere between 200 and 300 per week in the latter half of 2008, as opposed to a peak of nearly 1,600 in summer 2007. The number of Iraqi security forces killed was under 100 per month in the second half of 2008, from a high of 200 to 300 in the summer of 2007.[254]

Meanwhile, the proficiency of the Iraqi military increased as it launched a spring offensive against Shia militias, which Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki had previously been criticized for allowing to operate. This began with a March operation against the Mahdi Army in Basra, which led to fighting in Shia areas up and down the country, especially in the Sadr City district of Baghdad. By October, the British officer in charge of Basra said that since the operation, the town had become "secure" and had a murder rate comparable to Manchester in England.[255] The US military also said there had been a decrease of about a quarter in the quantity of Iranian-made explosives found in Iraq in 2008, possibly indicating a change in Iranian policy.[256]

Progress in Sunni areas continued after members of the Awakening movement were transferred from US military to Iraqi control.[257] In May, the Iraqi army – backed by coalition support – launched an offensive in Mosul, the last major Iraqi stronghold of al-Qaeda. Despite detaining thousands of individuals, the offensive failed to lead to major long-term security improvements in Mosul. At the end of the year, the city remained a major flashpoint.[258][259]

In the regional dimension, the ongoing conflict between Turkey and PKK[260][261][262] intensified on 21 February, when Turkey launched a ground attack into the Quandeel Mountains of Northern Iraq. In the nine-day-long operation, around 10,000 Turkish troops advanced up to 25 km into Northern Iraq. This was the first substantial ground incursion by Turkish forces since 1995.[263][264]

Shortly after the incursion began, both the Iraqi cabinet and the Kurdistan regional government condemned Turkey's actions and called for the immediate withdrawal of Turkish troops from the region.[265] Turkish troops withdrew on 29 February.[266] The fate of the Kurds and the future of the ethnically diverse city of Kirkuk remained a contentious issue in Iraqi politics.

US military officials met these trends with cautious optimism as they approached what they described as the "transition" embodied in the US–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, which was negotiated throughout 2008.[253] The commander of the coalition, US General Raymond T. Odierno, noted that "in military terms, transitions are the most dangerous time" in December 2008.[253]

Spring offensives on Shiite militias

[edit]

At the end of March, the Iraqi Army, with coalition air support, launched an offensive, dubbed "Charge of the Knights", in Basra to secure the area from militias. This was the first major operation where the Iraqi Army did not have direct combat support from conventional coalition ground troops. The offensive was opposed by the Mahdi Army, one of the militias, which controlled much of the region.[267][268] Fighting quickly spread to other parts of Iraq: including Sadr City, Al Kut, Al Hillah and others. During the fighting Iraqi forces met stiff resistance from militiamen in Basra to the point that the Iraqi military offensive slowed to a crawl, with the high attrition rates finally forcing the Sadrists to the negotiating table.

Following intercession by the Iranian government, al‑Sadr ordered a ceasefire on 30 March 2008.[269] The militiamen kept their weapons.

By 12 May 2008, Basra "residents overwhelmingly reported a substantial improvement in their everyday lives" according to The New York Times. "Government forces have now taken over Islamic militants' headquarters and halted the death squads and 'vice enforcers' who attacked women, Christians, musicians, alcohol sellers and anyone suspected of collaborating with Westerners", according to the report; however, when asked how long it would take for lawlessness to resume if the Iraqi army left, one resident replied, "one day".[268]

In late April roadside bombings continued to rise from a low in January – from 114 bombings to more than 250, surpassing the May 2007 high.

Congressional testimony

[edit]

Speaking before Congress on 8 April 2008, General David Petraeus urged delaying troop withdrawals, saying, "I've repeatedly noted that we haven't turned any corners, we haven't seen any lights at the end of the tunnel," referencing the comments of then-President Bush and former Vietnam-era General William Westmoreland.[270] When asked by the Senate if reasonable people could disagree on the way forward, Petraeus said, "We fight for the right of people to have other opinions."[271]

Upon questioning by then Senate committee chair Joe Biden, Ambassador Crocker admitted that Al‑Qaeda in Iraq was less important than the Al Qaeda organization led by Osama bin Laden along the Afghan-Pakistani border.[272] Lawmakers from both parties complained that US taxpayers are carrying Iraq's burden as it earns billions of dollars in oil revenues.

Iraqi security forces rearm

[edit]Iraq became one of the top purchasers of US military equipment with their army trading its AK‑47 assault rifles for the US M‑16 and M‑4 rifles, among other equipment.[273] In 2008 alone, Iraq accounted for more than $12.5 billion of the $34 billion US weapon sales to foreign countries (not including the potential F-16 fighter planes.).[274]

Iraq sought 36 F‑16s, the most sophisticated weapons system Iraq has attempted to purchase. The Pentagon notified Congress that it had approved the sale of 24 American attack helicopters to Iraq, valued at as much as $2.4 billion. Including the helicopters, Iraq announced plans to purchase at least $10 billion in US tanks and armored vehicles, transport planes, and other battlefield equipment and services. Over the summer, the Defense Department announced that the Iraqi government wanted to order more than 400 armored vehicles and other equipment worth up to $3 billion, and six C-130J transport planes, worth up to $1.5 billion.[275][276] From 2005 to 2008, the United States had completed approximately $20 billion in arms sales agreements with Iraq.[277]

Status of forces agreement

[edit]The US–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement was approved by the Iraqi government on 4 December 2008.[278] It established that US combat forces would withdraw from Iraqi cities by 30 June 2009, and that all US forces would be completely out of Iraq by 31 December 2011. The pact was subject to possible negotiations which could have delayed withdrawal and a referendum scheduled for mid-2009 in Iraq, which might have required all US forces to completely leave by the middle of 2010.[279][280] The pact required criminal charges for holding prisoners over 24 hours, and required a warrant for searches of homes and buildings that are not related to combat.[281]

US contractors working for US forces were to be subject to Iraqi criminal law, while contractors working for the State Department and other US agencies may retain their immunity. If US forces commit still undecided "major premeditated felonies" while off-duty and off-base, they will be subject to the still undecided procedures laid out by a joint US‑Iraq committee if the United States certifies the forces were off-duty.[282][283][284][285]

Some Americans have discussed "loopholes"[286] and some Iraqis have said they believe parts of the pact remain a "mystery".[287] US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates predicted that after 2011 he expected to see "perhaps several tens of thousands of American troops" as part of a residual force in Iraq.[288]

Several groups of Iraqis protested the passing of the SOFA accord[289][290][291] as prolonging and legitimizing the occupation. Tens of thousands of Iraqis burned an effigy of George W. Bush in a central Baghdad square where US troops five years previously organized a tearing down of a statue of Saddam Hussein.[161][287][292] Some Iraqis expressed skeptical optimism that the US would completely end its presence by 2011.[293] On 4 December 2008, Iraq's presidential council approved the security pact.[278]

A representative of Grand Ayatollah Ali Husseini al‑Sistani expressed concern with the ratified version of the pact and noted that the government of Iraq has no authority to control the transfer of occupier forces into and out of Iraq, no control of shipments and that the pact grants the occupiers immunity from prosecution in Iraqi courts. He said that Iraqi rule in the country is not complete while the occupiers are present, but that ultimately the Iraqi people would judge the pact in a referendum.[292] Thousands of Iraqis have gathered weekly after Friday prayers and shouted anti‑US and anti-Israeli slogans protesting the security pact between Baghdad and Washington. A protester said that despite the approval of the Interim Security pact, the Iraqi people would break it in a referendum next year.[294]

2009: Coalition redeployment

[edit]Transfer of the Green Zone

[edit]

On 1 January 2009, the United States handed control of the Green Zone and Saddam Hussein's presidential palace to the Iraqi government in a ceremonial move described by the country's prime minister as a restoration of Iraq's sovereignty. Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki said he would propose 1 January be declared national "Sovereignty Day". "This palace is the symbol of Iraqi sovereignty and by restoring it, a real message is directed to all Iraqi people that Iraqi sovereignty has returned to its natural status", al‑Maliki said.[295]

The US military attributed a decline in reported civilian deaths to several factors including the US‑led "troop surge", the growth of US-funded Awakening Councils, and Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr's call for his militia to abide by a cease fire.[296]

Provincial elections

[edit]On 31 January, Iraq held provincial elections.[297] Provincial candidates and those close to them faced some political assassinations and attempted assassinations, and there was also some other violence related to the election.[298][299][300][301]

Iraqi voter turnout failed to meet the original expectations which were set and was the lowest on record in Iraq,[302] but US Ambassador Ryan Crocker characterized the turnout as "large".[303] Of those who turned out to vote, some groups complained of disenfranchisement and fraud.[302][304][305] After the post-election curfew was lifted, some groups made threats about what would happen if they were unhappy with the results.[306]

Exit strategy announcement

[edit]On 27 February, United States President Barack Obama gave a speech at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune in the US state of North Carolina announcing that the US combat mission in Iraq would end by 31 August 2010. A "transitional force" of up to 50,000 troops tasked with training the Iraqi Security Forces, conducting counterterrorism operations, and providing general support may remain until the end of 2011, the president added. However, the insurgency in 2011 and the rise of ISIL in 2014 caused the war to continue.[307]

The day before Obama's speech, Prime Minister of Iraq Nouri al‑Maliki said at a press conference that the government of Iraq had "no worries" over the impending departure of US forces and expressed confidence in the ability of the Iraqi Security Forces and police to maintain order without US military support.[308]

Sixth anniversary protests

[edit]On 9 April, the 6th anniversary of Baghdad's fall to coalition forces, tens of thousands of Iraqis thronged Baghdad to mark the anniversary and demand the immediate departure of coalition forces. The crowds of Iraqis stretched from the Sadr City slum in northeast Baghdad to the square around 5 km (3.1 mi) away, where protesters burned an effigy featuring the face of US President George W. Bush.[309] There were also Sunni Muslims in the crowd. Police said many Sunnis, including prominent leaders such as a founding sheikh from the Sons of Iraq, took part.[310]

Coalition forces withdraw

[edit]On 30 April, the United Kingdom formally ended combat operations. Prime Minister Gordon Brown characterized the operation in Iraq as a "success story" because of UK troops' efforts. Britain handed control of Basra to the United States Armed Forces.[311]

The withdrawal of US forces began at the end of June, with 38 bases to be handed over to Iraqi forces. On 29 June 2009, US forces withdrew from Baghdad. On 30 November 2009, Iraqi Interior Ministry officials reported that the civilian death toll in Iraq fell to its lowest level in November since the 2003 invasion.[312]

On 28 July, Australia withdrew its combat forces as the Australian military presence in Iraq ended, per an agreement with the Iraqi government.

Iraq awards oil contracts

[edit]

On 30 June and 11 December 2009, the Iraqi ministry of oil awarded contracts to international oil companies for some of Iraq's many oil fields. The winning oil companies entered joint ventures with the Iraqi ministry of oil, and the terms of the awarded contracts included extraction of oil for a fixed fee of approximately $1.40 per barrel.[313][314][315] The fees will only be paid once a production threshold set by the Iraqi ministry of oil is reached.

2010: US drawdown and Operation New Dawn

[edit]On 17 February 2010, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates announced that as of 1 September, the name "Operation Iraqi Freedom" would be replaced by "Operation New Dawn".[316]

On 18 April, US and Iraqi forces killed Abu Ayyub al-Masri, the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq in a joint American and Iraqi operation near Tikrit, Iraq.[317] The coalition forces believed al-Masri to be wearing a suicide vest and proceeded cautiously. After the lengthy exchange of fire and bombing of the house, the Iraqi troops stormed inside and found two women still alive, one of whom was al-Masri's wife, and four dead men, identified as al-Masri, Abu Abdullah al-Rashid al-Baghdadi, an assistant to al-Masri, and al-Baghdadi's son. A suicide vest was indeed found on al-Masri's corpse, as the Iraqi Army subsequently stated.[318] Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki announced the killings of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Ayyub al-Masri at a news conference in Baghdad and showed reporters photographs of their bloody corpses. "The attack was carried out by ground forces which surrounded the house, and also through the use of missiles," Maliki said. "During the operation computers were seized with e-mails and messages to the two biggest terrorists, Osama bin Laden and [his deputy] Ayman al-Zawahiri", Maliki added. US forces commander Gen. Raymond Odierno praised the operation. "The death of these terrorists is potentially the most significant blow to al‑Qaeda in Iraq since the beginning of the insurgency", he said. "There is still work to do but this is a significant step forward in ridding Iraq of terrorists."

On 20 June, Iraq's Central Bank was bombed in an attack that left 15 people dead and brought much of downtown Baghdad to a standstill. The attack was claimed to have been carried out by the Islamic State of Iraq. This attack was followed by another attack on Iraq's Bank of Trade building that killed 26 and wounded 52 people.[319]

In late August 2010, insurgents conducted a major attack with at least 12 car bombs simultaneously detonating from Mosul to Basra and killing at least 51. These attacks coincided with the US plans for a withdrawal of combat troops.[320]

From the end of August 2010, the United States attempted to dramatically cut its combat role in Iraq, with the withdrawal of all US ground forces designated for active combat operations. The last US combat brigades departed Iraq in the early morning of 19 August. Convoys of US troops had been moving out of Iraq to Kuwait for several days, and NBC News broadcast live from Iraq as the last convoy crossed the border. While all combat brigades left the country, an additional 50,000 personnel (including Advise and Assist Brigades) remained in the country to provide support for the Iraqi military.[321][322] These troops were required to leave Iraq by 31 December 2011 under an agreement between the US and Iraqi governments.[323]

The desire to step back from an active counter-insurgency role did not however mean that the Advise and Assist Brigades and other remaining US forces would not be caught up in combat. A standards memo from the Associated Press reiterated "combat in Iraq is not over, and we should not uncritically repeat suggestions that it is, even if they come from senior officials".[324]

State Department spokesman P. J. Crowley stated "... we are not ending our work in Iraq, We have a long-term commitment to Iraq."[325] On 31 August, from the Oval Office, Barack Obama announced his intent to end the combat mission in Iraq. In his address, he covered the role of the United States' soft power, the effect the war had on the United States economy, and the legacy of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.[326]

On the same day in Iraq, at a ceremony at one of Saddam Hussein's former residences at Al-Faw Palace in Baghdad, a number of US dignitaries spoke in a ceremony for television cameras, avoiding overtones of the triumphalism present in US announcements made earlier in the war. Vice President Joe Biden expressed concerns regarding the ongoing lack of progress in forming a new Iraqi government, saying of the Iraqi people that "they expect a government that reflects the results of the votes they cast". Gen. Ray Odierno stated that the new era "in no way signals the end of our commitment to the people of Iraq". Speaking in Ramadi earlier in the day, Gates said that US forces "have accomplished something really quite extraordinary here, [but] how it all weighs in the balance over time I think remains to be seen". When asked by reporters if the seven-year war was worth doing, Gates commented that "It really requires a historian's perspective in terms of what happens here in the long run". He noted the Iraq War "will always be clouded by how it began" regarding Saddam Hussein's supposed weapons of mass destruction, which were never confirmed to have existed. Gates continued, "This is one of the reasons that this war remains so controversial at home".[327] On the same day Gen. Ray Odierno was replaced by Lloyd Austin as Commander of US forces in Iraq.

On 7 September, two US troops were killed and nine wounded in an incident at an Iraqi military base. The incident is under investigation by Iraqi and US forces, but it is believed that an Iraqi soldier opened fire on US forces.[328]

On 8 September, the US Army announced the arrival in Iraq of the first specifically designated Advise and Assist Brigade, the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment. It was announced that the unit would assume responsibilities in five southern governorates.[329] From 10 to 13 September, Second Advise and Assist Brigade, 25th Infantry Division fought Iraqi insurgents near Diyala.

According to reports from Iraq, hundreds of members of the Sunni Awakening Councils may have switched allegiance back to the Iraqi insurgency or al-Qaeda.[330]

In October, WikiLeaks disclosed 391,832 classified US military documents on the Iraq War.[331][332][333] Approximately, 58 people were killed with another 40 wounded in an attack on the Sayidat al‑Nejat church, a Chaldean Catholic church in Baghdad. Responsibility for the attack was claimed by the Islamic State in Iraq organization.[334]

Coordinated attacks in primarily Shia areas struck throughout Baghdad on 2 November, killing approximately 113 and wounding 250 with around 17 bombs.[335]

Iraqi arms purchases

[edit]

As US forces departed the country, the Iraq Defense Ministry solidified plans to purchase advanced military equipment from the United States. Plans in 2010 called for $13 billion of purchases, to include 140 M1 Abrams main battle tanks.[336] In addition to the $13 billion purchase, the Iraqis also requested 18 F-16 Fighting Falcons as part of a $4.2 billion program that also included aircraft training and maintenance, AIM‑9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, laser-guided bombs and reconnaissance equipment.[337] All Abrams tanks were delivered by the end of 2011,[338] but the first F-16s did not arrive in Iraq until 2015, due to concerns that the Islamic State might overrun Balad Air Base.[339]

The Iraqi Navy also purchased 12 US‑built Swift-class patrol boats, at a cost of $20 million each. Delivery was completed in 2013.[340] The vessels are used to protect the oil terminals at Basra and Khor al-Amiya.[337] Two US‑built offshore support vessels, each costing $70 million, were delivered in 2011.[341]

The UN lifts restrictions on Iraq

[edit]In a move to legitimize the existing Iraqi government, the United Nations lifted the Saddam Hussein-era UN restrictions on Iraq. These included allowing Iraq to have a civilian nuclear program, permitting the participation of Iraq in international nuclear and chemical weapons treaties, as well as returning control of Iraq's oil and gas revenue to the government and ending the Oil-for-Food Programme.[342]

2011: US withdrawal

[edit]Muqtada al-Sadr returned to Iraq in the holy city of Najaf to lead the Sadrist movement after being in exile since 2007.[343]

June 2011, became the bloodiest month in Iraq for the US military since June 2009, with 15 US soldiers killed, only one of them outside combat.[344]

On 7 July, two US troops were killed and one seriously injured in an IED attack at Victory Base Complex outside Baghdad. They were members of the 145th Brigade Support Battalion, 116th Cavalry Heavy Brigade Combat Team, an Idaho Army National Guard unit base in Post Falls, Idaho. Spc. Nathan R. Beyers, 24, and Spc. Nicholas W. Newby, 20, were killed in the attack, Staff Sgt. Jazon Rzepa, 30, was seriously injured.[345]

In September, Iraq signed a contract to buy 18 Lockheed Martin F-16 warplanes, becoming the 26th nation to operate the F-16. Because of windfall profits from oil, the Iraqi government is planning to double this originally planned 18, to 36 F-16s. Iraq is relying on the US military for air support as it rebuilds its forces and battles a stubborn Islamist insurgency.[346]

With the collapse of the discussions about extending the stay of any US troops beyond 2011, where they would not be granted any immunity from the Iraqi government, on 21 October 2011, President Obama announced at a White House press conference that all remaining US troops and trainers would leave Iraq by the end of the year as previously scheduled, bringing the US mission in Iraq to an end.[347][348][349][350][351][352] The last American soldier to die in Iraq before the withdrawal, SPC. David Hickman, was killed by a roadside bomb in Baghdad on 14 November.[353]

In November 2011, the US Senate voted down a resolution to formally end the war by bringing its authorization by Congress to an end.[354]

On 15 December, an American military ceremony was held in Baghdad putting a formal end to the US mission in Iraq.[355]

The last US combat troops withdrew from Iraq on 18 December 2011, although the US embassy and consulates continue to maintain a staff of more than 20,000 including 100+ military personnel within the Office of Security Cooperation-Iraq (OSC-I),[356] US Marine Embassy Guards and between 4,000 and 5,000 private military contractors.[357][358] The next day, Iraqi officials issued an arrest warrant for the Sunni Vice-president Tariq al-Hashimi. He has been accused of involvement in assassinations and fled to the Kurdish part of Iraq.[359]

Aftermath

[edit]Emerging conflict and insurgency

[edit]

The invasion and occupation led to sectarian violence, which caused widespread displacement among Iraqi civilians. Since the beginning of the war, the first parliamentary elections were held in 2005 which brought greater representation and autonomy to Iraqi Kurds. By 2007 the Iraqi Red Crescent estimated 2.3 million Iraqis were internally displaced, with an estimated 2 million Iraqis fleeing to neighboring countries, mostly to Syria and Jordan.[360]

Sectarian violence continued in the first half of 2013. At least 56 people died in April when a Sunni protest in Hawija was interrupted by a government-supported helicopter raid and a series of violent incidents occurred in May. On 20 May 2013, at least 95 people died in a wave of car bomb attacks that was preceded by a car bombing on 15 May that led to 33 deaths; also, on 18 May 76 people were killed in the Sunni areas of Baghdad. Some experts have stated that Iraq could return to the brutal sectarian conflict of 2006.[361][362]

On 22 July 2013, at least five hundred convicts, most of whom were senior members of al-Qaida who had received death sentences, were freed from Abu Ghraib jail in an insurgent attack, which began with a suicide bomb attack on the prison gates.[363] James F. Jeffrey, the United States ambassador in Baghdad when the last American troops exited, said the assault and resulting escape "will provide seasoned leadership and a morale boost to Al Qaeda and its allies in both Iraq and Syria ... it is likely to have an electrifying impact on the Sunni population in Iraq, which has been sitting on the fence."[364]

By mid-2014 Iraq was in chaos with a new government yet to be formed following national elections, and the insurgency reaching new heights. In early June 2014 the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) took over the cities of Mosul and Tikrit and said it was ready to march on Baghdad, while Iraqi Kurdish forces took control of key military installations in the major oil city of Kirkuk. The al-Qaida breakaway group formally declared the creation of an Islamic state on 29 June 2014, in the territory under its control.[365]

Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki unsuccessfully asked his parliament to declare a state of emergency that would give him increased powers.[366] On 14 August 2014, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki succumbed to pressure at home and abroad to step down. This paved the way for Haidar al-Abadi to take over on 19 August 2014.