Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Italy

View on Wikipedia

Italy,[a] officially the Italian Republic,[b] is a country in Southern and Western Europe.[c] It consists of a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land border, as well as nearly 800 islands, notably Sicily and Sardinia. Italy shares land borders with France to the west; Switzerland and Austria to the north; Slovenia to the east; and the two enclaves of Vatican City and San Marino. It is the tenth-largest country in Europe by area, covering 301,340 km2 (116,350 sq mi), and the third-most populous member state of the European Union, with nearly 59 million inhabitants. Italy's capital and largest city is Rome; other major cities include Milan, Naples, Turin, Palermo, Bologna, Florence, Genoa, and Venice.

Key Information

The history of Italy goes back to numerous Italic peoples – notably including the ancient Romans, who conquered the Mediterranean world during the Roman Republic and ruled it for centuries during the Roman Empire. With the spread of Christianity, Rome became the seat of the Catholic Church and the Papacy. Barbarian invasions and other factors led to the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire between late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. By the 11th century, Italian city-states and maritime republics expanded, bringing renewed prosperity through commerce and laying the groundwork for modern capitalism. The Italian Renaissance flourished during the 15th and 16th centuries and spread to the rest of Europe. Italian explorers discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, contributing significantly to the Age of Discovery.

After centuries of political and territorial divisions, Italy was almost entirely unified in 1861, following wars of independence and the Expedition of the Thousand, establishing the Kingdom of Italy. From the late 19th to the early 20th century, Italy industrialised and acquired a colonial empire, while the south remained largely impoverished, fuelling a large immigrant diaspora to the Americas. From 1915 to 1918, Italy took part in World War I with the Entente against the Central Powers. In 1922, the Italian fascist dictatorship was established. During World War II, Italy was first part of the Axis until an armistice with the Allied powers (1940–1943), then a co-belligerent of the Allies during the Italian resistance and the liberation of Italy (1943–1945). Following the war, the monarchy was replaced by a republic and the country made a strong recovery.

A developed country with an advanced economy, Italy has the eighth-largest nominal GDP in the world, the second-largest manufacturing sector in Europe, and plays a significant role in regional and – to a lesser extent – global economic, military, cultural, and political affairs. It is a founding and leading member of the European Union, and is part of numerous other international organizations and forums. As a cultural superpower, Italy has long been a renowned global centre of art, music, literature, cuisine, fashion, science and technology, and the source of multiple inventions and discoveries. It has the highest number of World Heritage Sites (61) and is the fifth-most visited country in the world.

Name

[edit]Hypotheses for the etymology of Italia are numerous.[13] One theory suggests it originated from an Ancient Greek term for the land of the Italói, a tribe that resided in the region now known as Calabria. Originally thought to be named Vituli, some scholars suggest their totemic animal to be the calf (Latin: vitulus; Umbrian: vitlo; Oscan: Víteliú).[14] Several ancient authors said it was named after a local ruler Italus.[15]

The ancient Greek term for Italy initially referred only to the south of the Bruttium peninsula and parts of Catanzaro and Vibo Valentia. The larger concept of Oenotria and "Italy" became synonymous, and the name applied to most of Lucania as well. Before the Roman Republic's expansion, the name was used by Greeks for the land between the strait of Messina and the line connecting the gulfs of Salerno and Taranto, corresponding to Calabria. The Greeks came to apply "Italia" to a larger region.[16] In addition to the "Greek Italy" in the south, historians have suggested the existence of an "Etruscan Italy", which consisted of areas of central Italy.[17]

The borders of Roman Italy, Italia, are better established. Cato's Origines describes Italy as the entire peninsula south of the Alps.[18] In 264 BC, Roman Italy extended from the Arno and Rubicon rivers of the centre-north to the entire south. The northern area, Cisalpine Gaul, considered geographically part of Italy, was occupied by Rome in the 220s BC,[19] but remained politically separated. It was legally merged into the administrative unit of Italy in 42 BC.[20] Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, and Malta were added to Italy by Diocletian in 292 AD,[21] which made late-ancient Italy coterminous with the modern Italian geographical region.[22]

The Latin Italicus was used to describe "a man of Italy" as opposed to a provincial, or one from the Roman province.[23] The adjective italianus, from which Italian was derived, is from medieval Latin and was used alternatively with Italicus during the early modern period.[24] After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy was created. After the Lombard invasions, Italia was retained as the name for their kingdom, and its successor kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire.[25]

History

[edit]Prehistory and antiquity

[edit]

Lower Paleolithic artefacts, dating back 850,000 years, have been recovered from Monte Poggiolo.[26] Excavations throughout Italy revealed a Neanderthal presence in the Middle Palaeolithic period 200,000 years ago,[27] while modern humans appeared about 40,000 years ago at Riparo Mochi.[28]

The ancient peoples of pre-Roman Italy were Indo-European, specifically the Italic peoples. The main historic peoples of possible non-Indo-European or pre-Indo-European heritage include the Etruscans, the Elymians and Sicani of Sicily, and the prehistoric Sardinians, who gave birth to the Nuragic civilisation. Other ancient populations include the Rhaetian people and Camunni, known for their rock drawings in Valcamonica.[29] A natural mummy, Ötzi, dated 3400–3100 BC, was discovered in the Similaun glacier in 1991.[30]

The first colonisers were the Phoenicians, who established emporiums on the coasts of Sicily and Sardinia. Some became small urban centres and developed parallel to Greek colonies.[31] During the 8th and 7th centuries, Greek colonies were established at Pithecusae, eventually extending along the south of the Italian Peninsula and the coast of Sicily, an area later known as Magna Graecia.[32] Ionians, Doric colonists, Syracusans, and the Achaeans founded various cities. Greek colonisation placed the Italic peoples in contact with democratic forms of government and high artistic and cultural expressions.[33]

Ancient Rome

[edit]Italy's history goes back to numerous Italic peoples – notably including the ancient Romans, who conquered the Mediterranean world during the Roman Republic and ruled it for centuries during the Roman Empire.[35]

Ancient Rome, a settlement on the River Tiber in central Italy, founded in 753 BC, was ruled for 244 years by a monarchical system.[36] In 509 BC, the Romans, favouring a government of the Senate and the People (SPQR), expelled the monarchy and established an oligarchic republic.[37]

The Italian Peninsula, named Italia, was consolidated into a unified entity during Roman expansion, the conquest of new territories often at the expense of the other Italic tribes, Etruscans, Celts, and Greeks. A permanent association, with most of the local tribes and cities, was formed, and Rome began the conquest of Western Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. In the wake of Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, Rome grew into a massive empire stretching from Britain to the borders of Persia, engulfing the whole Mediterranean basin, in which Greek, Roman, and other cultures merged into a powerful civilisation. The long reign of the first emperor, Augustus, began an age of peace and prosperity. Roman Italy remained the metropole of the empire, homeland of the Romans and territory of the capital.[38]

The Roman Empire was among the largest in history, wielding great economical, cultural, political, and military power.[39] At its greatest extent, it had an area of 5 million square kilometres (1.9 million square miles).[40] The Roman legacy has deeply influenced Western civilisation shaping the modern world. The widespread use of Romance languages derived from Latin, numerical system, modern Western alphabet and calendar, and the emergence of Christianity as a world religion, are among the many legacies of Roman dominance.[41]

Middle Ages

[edit]After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy fell under the Odoacer's kingdom, and was seized by the Ostrogoths.[42] Invasions resulted in a chaotic succession of kingdoms and the supposed "Dark Ages". The invasion of another Germanic tribe in the 6th century, the Lombards, reduced Byzantine presence and ended political unity of the peninsula. The north formed the Lombard kingdom, central-south was also controlled by the Lombards, and other parts remained Byzantine.[43]

The Lombard kingdom was absorbed into Francia by Charlemagne in the late 8th century and became the Kingdom of Italy.[44] The Franks helped form the Papal States. Until the 13th century, politics was dominated by relations between the Holy Roman Emperors and the Papacy, with city-states siding with the former (Ghibellines) or with the latter (Guelphs) for momentary advantage.[45] The Germanic emperor and Roman pontiff became the universal powers of medieval Europe. However, conflict over the Investiture Controversy and between Guelphs and Ghibellines ended the imperial-feudal system in the north, where cities gained independence.[46] In 1176, the Lombard League of city-states defeated Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, ensuring their independence.

City-states – e.g. Milan, Florence, Venice – played a crucially innovative role in financial development by devising banking practices, and enabling new forms of social organisation.[47] In coastal and southern areas, maritime republics dominated the Mediterranean and monopolised trade to the Orient. They were independent thalassocratic city-states, in which merchants had considerable power. Although oligarchical, the relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement.[48] The best-known maritime republics were Venice, Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi.[49] Each had dominion over overseas lands, islands, lands on the Adriatic, Aegean, and Black seas, and commercial colonies in the Near East and North Africa.[50]

Venice and Genoa were Europe's gateways to the East, and producers of fine glass, while Florence was a centre of silk, wool, banking, and jewellery. The wealth generated meant large public and private artistic projects could be commissioned. The republics participated in the Crusades, providing support, transport, but mostly taking political and trading opportunities.[48] Italy first felt the economic changes which led to the commercial revolution: Venice was able to sack Byzantine's capital and finance Marco Polo's voyages to Asia; the first universities were formed in Italian cities, and scholars such as Aquinas obtained international fame; capitalism and banking families emerged in Florence, where Dante and Giotto were active around 1300.[51] In the south, Sicily had become an Arab Islamic emirate in the 9th century, thriving until the Italo-Normans conquered it in the late 11th century, together with most of the Lombard and Byzantine principalities of southern Italy.[52] The region was subsequently divided between the Kingdom of Sicily and Kingdom of Naples.[d][53] The Black Death of 1348 killed perhaps a third of Italy's population.[54]

Early modern period

[edit]

During the 1400s and 1500s, Italy was the birthplace and heart of the Renaissance. This era marked the transition from the medieval period to the modern age and was fostered by the wealth accumulated by merchant cities and the patronage of dominant families.[55] Italian polities were now regional states effectively ruled by princes, in control of trade and administration, and their courts became centres of the arts and sciences. These princedoms were led by political dynasties and merchant families, such as the Medici of Florence. After the end of the Western Schism, newly elected Pope Martin V returned to the Papal States and restored Italy as the sole centre of Western Christianity. The Medici Bank was made the credit institution of the Papacy, and significant ties were established between the Church and new political dynasties.[55][56]

In 1453, despite activity by Pope Nicholas V to support the Byzantines, the city of Constantinople fell to the Ottomans. This led to the migration of Greek scholars and texts to Italy, fuelling the rediscovery of Greek humanism.[57] Humanist rulers such as Federico da Montefeltro and Pope Pius II worked to establish ideal cities, founding Urbino and Pienza. Pico della Mirandola wrote the Oration on the Dignity of Man, considered the manifesto of the Renaissance. In the arts, the Italian Renaissance exercised a dominant influence on European art for centuries, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giotto, Donatello, and Titian, and architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi, Andrea Palladio, and Donato Bramante. Italian explorers and navigators from the maritime republics, eager to find an alternative route to the Indies to bypass the Ottomans, offered their services to monarchs of Atlantic countries and played a key role in ushering the Age of Discovery and colonization of the Americas. The most notable were: Christopher Columbus, who opened the Americas for conquest by Europeans;[58] John Cabot, the first European to explore North America since the Norse;[59] and Amerigo Vespucci, for whom the continent of America is named.[60][61]

A defensive alliance known as the Italic League was formed between Venice, Naples, Florence, Milan, and the Papacy. Lorenzo the Magnificent de Medici was the Renaissance's greatest patron, his support allowed the League to abort invasion by the Turks. The alliance, however, collapsed in the 1490s; the invasion of Charles VIII of France initiated a series of wars in the peninsula. During the High Renaissance, popes such as Julius II (1503–1513) fought for control of Italy against foreign monarchs; Paul III (1534–1549) preferred to mediate between the European powers to secure peace. In the middle of such conflicts, the Medici popes Leo X (1513–1521) and Clement VII (1523–1534) faced the Protestant Reformation in Germany, England and elsewhere.

In 1559, at the end of the Italian wars between France and the Habsburgs, about half of Italy (the southern Kingdoms of Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, and the Duchy of Milan) was under Spanish rule, while the other half remained independent (many states continued to be formally part of the Holy Roman Empire). The Papacy launched the Counter-Reformation, whose key events include: the Council of Trent (1545–1563); adoption of the Gregorian calendar; the Jesuit China mission; the French Wars of Religion; end of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648); and the Great Turkish War. The Italian economy declined in the 1600s and 1700s.

During the War of the Spanish Succession (1700–1714), Austria acquired most of the Spanish domains in Italy, namely Milan, Naples and Sardinia; the latter was given to the House of Savoy in exchange for Sicily in 1720. Later, a branch of the Bourbons ascended to the throne of Sicily and Naples. During the Napoleonic Wars, north and central Italy were reorganised as Sister Republics of France and, later, as a Kingdom of Italy.[62] The south was administered by Joachim Murat, Napoleon's brother-in-law. 1814's Congress of Vienna restored the situation of the late 18th century, but the ideals of the French Revolution could not be eradicated, and re-surfaced during the political upheavals that characterised the early 19th century. The first adoption of the Italian tricolour by an Italian state, the Cispadane Republic, occurred during Napoleonic Italy, following the French Revolution, which advocated national self-determination.[63] This event is celebrated by Tricolour Day.[64]

Unification

[edit]The birth of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of efforts of Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula. By the mid-19th century, rising Italian nationalism led to revolution.[65] Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the political and social Italian unification movement, or Risorgimento, emerged to unite Italy by consolidating the states and liberating them from foreign control. A radical figure was the patriotic journalist Giuseppe Mazzini, founder of the political movement Young Italy in the 1830s, who favoured a unitary republic and advocated a broad nationalist movement. 1847 saw the first public performance of "Il Canto degli Italiani", which became the national anthem in 1946.[66]

The most famous member of Young Italy was the revolutionary and general Giuseppe Garibaldi[69] who led the republican drive for unification in southern Italy. However, the Italian monarchy of the House of Savoy, in the Kingdom of Sardinia, whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had ambitions of establishing a united Italian state. In the context of the 1848 liberal revolutions that swept Europe, an unsuccessful First Italian War of Independence was declared against Austria. In 1855, Sardinia became an ally of Britain and France in the Crimean War.[70] Sardinia fought the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating Lombardy. On the basis of the Plombières Agreement, the Sardinia ceded Savoy and Nice to France, an event that caused the Niçard exodus.[71]

In 1860–1861, Garibaldi led the drive for unification in Naples and Sicily.[72] Teano was the site of a famous meeting between Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II, the last king of Sardinia, during which Garibaldi shook Victor Emanuel's hand and hailed him as King of Italy. Cavour agreed to include Garibaldi's southern Italy in a union with the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. This allowed the Sardinian government to declare a united Italian kingdom on 17 March 1861,[73] with Victor Emmanuel II as its first king. In 1865, the kingdom's capital was moved from Turin to Florence. In 1866, Victor Emmanuel II, allied with Prussia during the Austro-Prussian War, waged the Third Italian War of Independence, which resulted in Italy annexing Venetia. Finally, in 1870, as France abandoned Rome during the Franco-Prussian War, the Italians captured the Papal States, unification was completed, and the capital moved to Rome.[67]

Liberal period

[edit]Sardinia's constitution was extended to all of Italy in 1861, and provided basic freedoms for the new state; but electoral laws excluded the non-propertied classes. The new kingdom was governed by a parliamentary constitutional monarchy dominated by liberals. As northern Italy quickly industrialised, southern and northern rural areas remained underdeveloped and overpopulated, forcing millions to migrate and fuelling a large and influential diaspora. The Italian Socialist Party increased in strength, challenging the traditional liberal and conservative establishment. In the last two decades of the 19th century, Italy developed into a colonial power[74] by subjugating Eritrea, Somalia, Tripolitania, and Cyrenaica in Africa.[75] In 1913, male universal suffrage was adopted. The pre-World War I period was dominated by Giovanni Giolitti, prime minister five times between 1892 and 1921.

Italy entered into the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity, so it is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence,[76] from a historiographical perspective, as the conclusion of the unification of Italy.[77] Italy, nominally allied with the German and Austro-Hungarian empires in the Triple Alliance, in 1915 joined the Allies, entering World War I with a promise of substantial territorial gains that included west Inner Carniola, the former Austrian Littoral, and Dalmatia, as well as parts of the Ottoman Empire. The country's contribution to the Allied victory earned it a place as one of the "Big Four" powers. Reorganisation of the army and conscription led to Italian victories. In October 1918, the Italians launched a massive offensive, culminating in victory at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto.[78] This marked the end of war on the Italian Front, secured dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and was instrumental in ending the war less than two weeks later.

During the war, more than 650,000 Italian soldiers and as many civilians died,[79] and the kingdom was on the brink of bankruptcy. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) and Treaty of Rapallo (1920) allowed for annexation of Trentino Alto-Adige, the Julian March, Istria, the Kvarner Gulf, and the Dalmatian city of Zara. The subsequent Treaty of Rome (1924) led to annexation of Fiume by Italy. Italy did not receive other territories promised by the Treaty of London, so this outcome was denounced as a "mutilated victory", by Benito Mussolini, which helped lead to the rise of Italian fascism. Historians regard "mutilated victory" as a "political myth", used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism.[80] Italy gained a permanent seat in the League of Nations's executive council.

Fascist regime and World War II

[edit]

The socialist agitations that followed the devastation of the Great War, inspired by the Russian Revolution, led to counter-revolution and repression throughout Italy. The liberal establishment, fearing a Soviet-style revolution, started to endorse the small National Fascist Party, led by Mussolini. In October 1922, the Blackshirts of the National Fascist Party organised a mass demonstration and the "March on Rome" coup. King Victor Emmanuel III appointed Mussolini as prime minister, transferring power to the fascists without armed conflict.[81] Mussolini banned political parties and curtailed personal liberties, establishing a dictatorship. These actions attracted international attention and inspired similar dictatorships in Nazi Germany and Francoist Spain.

Fascism was based upon Italian nationalism and imperialism, seeking to expand Italian possessions via irredentist claims based on the legacy of the Roman and Venetian empires.[82] For this reason the fascists engaged in interventionist foreign policy. In 1935, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia and founded Italian East Africa, resulting in international isolation. Italy withdrew from the League of Nations. Italy then allied with Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan, and strongly supported Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War. In April 1939, Italy invaded Albania.

Italy entered World War II on 10 June 1940. At this date, France practically had lost the Battle of France. At different times, Italians advanced in British Somaliland, Egypt, the Balkans, and eastern fronts. They were, however, defeated on the Eastern Front as well as in the East African and North African campaigns, losing their territories in Africa and the Balkans. Italian war crimes included extrajudicial killings and ethnic cleansing[83] by deportation of about 25,000 people – mainly Yugoslavs – to Italian concentration camps and elsewhere. Yugoslav Partisans perpetrated their own crimes against the ethnic Italian population during and after the war, including the foibe massacres. An Allied invasion of Sicily began in July 1943, leading to the collapse of the Fascist regime on 25 July. Mussolini was deposed and arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III. On 3 September, Italy signed the Armistice of Cassibile, ending its war with UK and USA. The Germans, with the assistance of Italian fascists, succeeded in taking control of north and central Italy (Operation Achse]). The country remained a battlefield, with the Allies moving up from the south.

In the north, the Germans set up the Italian Social Republic (RSI), a Nazi puppet state and collaborationist regime with Mussolini installed as leader after he was rescued by German paratroopers. What remained of the Italian troops was organised into the Italian Co-belligerent Army, which fought alongside the Allies, while other Italian forces, loyal to Mussolini, opted to fight alongside the Germans in the National Republican Army. German troops, with RSI collaboration, committed massacres and deported thousands of Jews to death camps. The post-armistice period saw the emergence of the Italian Resistance, who fought a guerrilla war against the Nazi German occupiers and collaborators.[84] An aspect of this period was the Italian civil war due to fighting between partisans and fascist RSI forces.[85][86] In April 1945, with defeat looming, Mussolini attempted to escape north,[87] but was captured and summarily executed by partisans.[88]

Hostilities ended on 29 April 1945, when the German forces in Italy surrendered. Nearly half a million Italians died in the war,[89] society was divided, and the economy all but destroyed – per capita income in 1944 was at its lowest point since 1900.[90] In the aftermath of the war there was a revival of Italian republicanism, leading to the 1946 Italian institutional referendum.[91]

Republican era

[edit]Italy became a republic after the 1946 referendum[92] held on 2 June, a day celebrated since as Festa della Repubblica. This was the first time women voted nationally.[93] Victor Emmanuel III's son, Umberto II, was forced to abdicate. The Republican Constitution was approved in 1948. Under the Treaty of Paris between Italy and the Allied Powers, areas next to the Adriatic Sea were annexed by Yugoslavia, resulting in the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, which involved the emigration of around 300,000 Istrian and Dalmatian Italians.[94] Italy lost all colonial possessions, ending the Italian Empire.

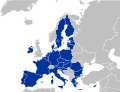

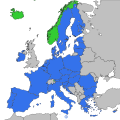

Fears of a Communist takeover proved crucial in 1948, when the Christian Democrats, under Alcide De Gasperi, won a landslide victory.[95] Consequently, in 1949 Italy became a member of NATO. The Marshall Plan revived the economy, which, until the late 1960s, enjoyed a period called the Italian economic miracle. In the 1950s, Italy became a founding country of the European Communities, a forerunner of the European Union. From the late 1960s until the early 1980s, the country experienced the Years of Lead, characterised by economic difficulties, especially after the 1973 oil crisis; social conflicts; and terrorist massacres.[96]

The economy recovered and Italy became the world's fifth-largest industrial nation after it gained entry into the G7 in the 1970s. However, national debt skyrocketed past 100% of GDP. Between 1992 and 1993, Italy faced terror attacks perpetrated by the Sicilian Mafia as a consequence of new anti-mafia measures by the government.[97] Voters – disenchanted with political paralysis, massive public debt and extensive corruption uncovered by the Clean Hands investigation – demanded radical reform. The Christian Democrats, who had ruled for almost 50 years, underwent a crisis and disbanded, splitting into factions.[98] The Communists reorganised as a social-democratic force. During the 1990s and 2000s, centre-right (dominated by media magnate Silvio Berlusconi) and centre-left coalitions (led by professor Romano Prodi) alternately governed.

In 2011, amidst the Great Recession, Berlusconi resigned and was replaced by the technocratic cabinet of Mario Monti.[99] In 2014, Matteo Renzi became prime minister and the government started constitutional reform. This was rejected in a 2016 referendum and Paolo Gentiloni became prime minister.[100]

During the European migrant crisis of the 2010s, Italy was the entry point and leading destination for most asylum seekers entering the EU. Between 2013 and 2018, it took in over 700,000 migrants,[101] mainly from sub-Saharan Africa,[102] which put a strain on the public purse and led to a surge in support for far-right or euro-sceptic parties.[103] After the 2018 general election, Giuseppe Conte became prime minister of a populist coalition.[104]

With almost 200,000 victims, Italy was one of the countries with the most deaths in the COVID-19 pandemic[105] and one of the most affected economically.[106] In February 2021, after a government crisis, Conte resigned. Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank, formed a national unity government supported by most main parties,[107] pledging to implement an economic stimulus to face the crisis caused by the pandemic.[108] In 2022, Giorgia Meloni was sworn in as Italy's first female prime minister.[109]

Geography

[edit]

Italy, whose territory largely coincides with the eponymous geographical region,[110] is located in Southern Europe[111] (and is also considered part of Western Europe[c]) between latitudes 35° and 47° N, and longitudes 6° and 19° E. To the north, from west to east, Italy borders France, Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia, and is roughly delimited by the Alpine watershed, enclosing the Po Valley and the Venetian Plain. It consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula, Sicily and Sardinia (the biggest islands of the Mediterranean), and many smaller islands.[110] Some of Italy's territory extends beyond the Alpine basin, and some islands are located outside the Eurasian continental shelf.

The country's area is 301,230 square kilometres (116,306 sq mi), of which 294,020 km2 (113,522 sq mi) is land and 7,210 km2 (2,784 sq mi) is water.[112] Including the islands, Italy has a coastline of 7,600 kilometres (4,722 miles) on the Mediterranean Sea, the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas,[113] the Ionian Sea,[114] and the Adriatic Sea.[115] Its border with France runs for 488 km (303 mi); Switzerland, 740 km (460 mi); Austria, 430 km (267 mi); and Slovenia, 232 km (144 mi). The sovereign states of San Marino and Vatican City (the smallest country in the world and headquarters of the worldwide Catholic Church under the governance of the Holy See) are enclaves within Italy,[116] while Campione d'Italia is an Italian exclave in Switzerland.[117] The border with San Marino is 39 km (24 mi) long; that with Vatican City is 3.2 km (2.0 mi).[112]

Over 35% of Italian territory is mountainous.[118] The Apennine Mountains form the peninsula's backbone, and the Alps form most of its northern boundary, where Italy's highest point is located on the summit of Mont Blanc (Monte Bianco) at 4,810 m (15,780 ft). Other well-known mountains include the Matterhorn (Monte Cervino) in the western Alps, and the Dolomites in the eastern Alps. Many parts of Italy are of volcanic origin. Most small islands and archipelagos in the south are volcanic islands. There are active volcanoes: Mount Etna in Sicily (the largest in Europe), Vulcano, Stromboli, and Vesuvius.

Most rivers of Italy drain into the Adriatic or Tyrrhenian Sea.[119] The longest is the Po, which flows from the Alps on the western border, and crosses the Padan plain to the Adriatic.[120] The Po Valley is the largest plain, with 46,000 km2 (18,000 sq mi), and contains over 70% of the country's lowlands.[118] The largest lakes are, in descending size: Garda (367.94 km2 or 142 sq mi), Maggiore (212.51 km2 or 82 sq mi), and Como (145.9 km2 or 56 sq mi).[121]

Climate

[edit]

Italy's climate is influenced by the seas that surround the country on every side except the north, which constitute a reservoir of heat and humidity. Within the southern temperate zone, they determine a Mediterranean climate with local differences.[123] Because of the length of the peninsula and the mostly mountainous hinterland, the climate is highly diverse. In most inland northern and central regions, the climate ranges from humid subtropical to humid continental and oceanic. The Po Valley is mostly humid subtropical, with cool winters and hot summers.[124] The coastal areas of Liguria, Tuscany, and most of the south generally fit the Mediterranean climate stereotype, as in the Köppen climate classification.

Conditions on the coast are different from those in the interior, particularly during winter when the higher altitudes tend to be cold, wet, and often snowy. The coastal regions have mild winters, and hot and generally dry summers; lowland valleys are hot in summer. Winter temperatures vary from 0 °C (32 °F) in the Alps to 12 °C (54 °F) in Sicily; so, average summer temperatures range from 20 °C (68 °F) to over 25 °C (77 °F). Winters can vary widely with lingering cold, foggy, and snowy periods in the north, and milder, sunnier conditions in the south. Summers are hot across the country, except at high altitude, particularly in the south. Northern and central areas can experience strong thunderstorms from spring to autumn.[125]

Biodiversity

[edit]Italy's varied geography, including the Alps, Apennines, central Italian woodlands, and southern Italian Garigue and Maquis shrubland, contribute to habitat diversity. As the peninsula is in the centre of the Mediterranean, forming a corridor between Central Europe and North Africa, and having 8,000 km (5,000 mi) of coastline, Italy has received species from the Balkans, Eurasia, and the Middle East. Italy has probably the highest level of faunal biodiversity in Europe, with over 57,000 species recorded, representing more than a third of all European fauna,[126] and the highest level of biodiversity of animal and plant species within the EU.[127]

The fauna of Italy includes 4,777 endemic animal species,[128] which include the Sardinian long-eared bat, Sardinian red deer, spectacled salamander, brown cave salamander, Italian newt, Italian frog, Apennine yellow-bellied toad, Italian wall lizard, and Sicilian pond turtle. There are 119 mammals species,[129] 550 bird species,[130] 69 reptile species,[131] 39 amphibian species,[132] 623 fish species,[133] and 56,213 invertebrate species, of which 37,303 are insect species.[134]

The flora of Italy was traditionally estimated to comprise about 5,500 vascular plant species.[135] However, as of 2005[update], 6,759 species are recorded in the Data bank of Italian vascular flora.[136] Italy has 1,371 endemic plant species and subspecies,[137] which include Sicilian fir, Barbaricina columbine, Sea marigold, Lavender cotton, and Ucriana violet. Italy is a signatory to the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats and the Habitats Directive.

Italy has many botanical and historic gardens.[138] The Italian garden is stylistically based on symmetry, axial geometry, and the principle of imposing order on nature. It influenced the history of gardening, especially French and English gardens.[139] The Italian garden was influenced by Roman and Italian Renaissance gardens.

The Italian wolf is the national animal of Italy,[140] while the national tree is the strawberry tree.[141] The reasons for this are that the Italian wolf, which inhabits the Apennine Mountains and the Western Alps, features prominently in Latin and Italian cultures, such as the legend of the founding of Rome,[142] while the green leaves, white flowers, and red berries of the strawberry tree, native to the Mediterranean, recall the colours of the flag.[141] The national bird is the Italian sparrow,[143] while the national flower is the flower of the strawberry tree.[144]

Environment

[edit]

After its quick industrial growth, Italy took time to address its environmental problems. After improvements, Italy now ranks 84th in the world for ecological sustainability.[145] The total area protected by national parks, regional parks, and nature reserves covers about 11% of Italian territory,[146] and 12% of Italy's coastline is protected.[147]

Italy has been one of the world's leading producers of renewable energy, in 2010 ranking as the fourth largest provider of installed solar energy capacity[148] and sixth largest of wind power capacity.[149] Renewable energy provided approximately 37% Italy's energy consumption in 2020.[150]

The country operated nuclear reactors between 1963 and 1990 but, after the Chernobyl disaster and referendums, the nuclear programme was terminated, a decision overturned by the government in 2008, with plans to build up to four nuclear power plants. This was in turn struck down by a referendum following the Fukushima nuclear accident.[151]

Air pollution remains severe, especially in the industrialised north. Italy is the twelfth-largest carbon dioxide producer.[152] Extensive traffic and congestion in large cities continue to cause environmental and health issues, even if smog levels have decreased since the 1970s and 1980s, with smog becoming an increasingly rare phenomenon and levels of sulphur dioxide decreasing.[153]

Deforestation, illegal building, and poor land-management policies have led to significant erosion in Italy's mountainous regions, leading to ecological disasters such as the 1963 Vajont Dam flood, the 1998 Sarno,[154] and the 2009 Messina mudslides.

Politics

[edit]Italy has been a unitary parliamentary republic since 1946, when the monarchy was abolished. The president of Italy, Sergio Mattarella since 2015, is Italy's head of state. The president is elected for a single seven-year term by the Italian Parliament and regional voters in joint session. Italy has a written democratic constitution that resulted from a Constituent Assembly formed by representatives of the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the liberation of Italy, in World War II.[155]

Italy plays a major role in several economic, military, cultural, and political affairs, and is one of the EU big three. It is widely considered to be a regional power,[156] while its great power status[157] is a subject of debate among scholars and political analysts.

According to International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices and Democracy Tracker, Italy performs in the high range on overall democratic measures, with particular weaknesses in rule of law.[158][159][160]

Government

[edit]Italy has a parliamentary government based on a mixed proportional and majoritarian voting system. The parliament is perfectly bicameral; each house has the same powers. The two houses: the Chamber of Deputies meets in Palazzo Montecitorio, and the Senate of the Republic in Palazzo Madama. A peculiarity of the Italian Parliament is the representation given to Italian citizens permanently living abroad: 8 Deputies and 4 Senators are elected in four distinct overseas constituencies. There are senators for life, appointed by the president "for outstanding patriotic merits in the social, scientific, artistic or literary field". Former presidents are ex officio life senators.

The prime minister of Italy is head of government and has executive authority, but must receive a vote of approval from the Council of Ministers to execute most policies. The prime minister and cabinet are appointed by the president, and confirmed by a vote of confidence in parliament. To remain as prime minister, one has to pass votes of confidence. The role of prime minister is similar to most other parliamentary systems, but they are not authorised to dissolve parliament. Another difference is that the political responsibility for intelligence is with the prime minister, who has exclusive power to coordinate intelligence policies, determine financial resources, strengthen cybersecurity, apply and protect State secrets, and authorise agents to carry out operations, in Italy or abroad.[161]

The major political parties are the Brothers of Italy, Democratic Party, and Five Star Movement. During the 2022 general election, these three and their coalitions won 357 of the 400 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, and 187 of 200 in the Senate. The centre-right coalition, which included Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy, Matteo Salvini's League, Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia, and Maurizio Lupi's Us Moderates, won most seats in parliament. The rest were taken by the centre-left coalition, which included the Democratic Party, the Greens and Left Alliance, Aosta Valley, More Europe, Civic Commitment, the Five Star Movement, Action – Italia Viva, South Tyrolean People's Party, South calls North, and the Associative Movement of Italians Abroad.

Law and criminal justice

[edit]

The law of Italy has several sources. These are hierarchical: the law or regulation from a lower source cannot conflict with the rule of an upper source (hierarchy of sources).[162] The Constitution of 1948 is the highest source.[163] The Constitutional Court of Italy rules on the conformity of laws with the constitution. The judiciary bases their decisions on Roman law modified by the Napoleonic Code and later statutes. The Supreme Court of Cassation is the highest court for both criminal and civil appeals.

Italy lags behind other Western European nations in LGBT rights.[164] Italy's law prohibiting torture is considered behind international standards.[165]

Law enforcement is complex with multiple police forces.[166] The national policing agencies are the Polizia di Stato ('State Police'), the Carabinieri, the Guardia di Finanza ('Financial Police'), and the Polizia Penitenziaria ('Prison Police'),[167] as well as the Guardia Costiera ('Coast Guard Police').[166] Although policing is primarily provided on a national basis,[167] there are also the provincial and municipal police.[166]

Since their appearance in the middle of the 19th century, Italian organised crime and criminal organisations have infiltrated the social and economic life of many regions in southern Italy; the most notorious is the Sicilian Mafia, which expanded into foreign countries, including the US. Mafia receipts may reach 9%[168] of GDP.[169] A 2009 report identified 610 comuni which have a strong Mafia presence, where 13 million Italians live and 15% of GDP is produced.[170] The Calabrian 'Ndrangheta, probably the most powerful crime syndicate of Italy, accounts alone for 3% of GDP.[171]

At 0.013 per 1,000 people, Italy has the 47th highest murder rate,[172] compared to 61 countries, and the 43rd highest number of rapes per 1,000 people, compared to 64 countries in the world. These are relatively low figures among developed countries.

Foreign relations

[edit]

Italy is a founding member of the European Economic Community (EEC), now the European Union (EU), and of NATO. Italy was admitted to the United Nations in 1955, and is a member and strong supporter of international organisations, such as the OECD, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade/World Trade Organization (GATT/WTO), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, and the Central European Initiative. Its turns in the rotating presidencies of international organisations include the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe in 2018, G7 in 2017, and the EU Council in 2014. Italy is a recurrent non-permanent member of the UN Security Council.

Italy strongly supports multilateral international politics, endorsing the UN and its international security activities. In 2013, Italy had 5,296 troops deployed abroad, engaged in 33 UN and NATO missions in 25 countries.[173] Italy deployed troops in support of UN peacekeeping missions in Somalia, Mozambique, and East Timor. Italy provides support for NATO and UN operations in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Albania, and deployed over 2,000 troops to Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) from 2003.

Italy supported international efforts to reconstruct and stabilise Iraq, but it had withdrawn its military contingent of 3,200 troops by 2006. In August 2006, Italy deployed about 2,450 troops for the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon.[174] Italy is one of the largest financiers of the Palestinian Authority, contributing €60 million in 2013 alone.[175]

Military

[edit]

The military history of Italy chronicles a vast time period, lasting from the military conflicts fought by the ancient peoples of Italy, most notably the conquest of the Mediterranean world by the ancient Romans, through the expansion of the Italian city-states and maritime republics during the medieval period and the involvement of the historical Italian states in the Italian Wars and the wars of succession, to the Napoleonic period, the Italian unification, the campaigns of the colonial empire, the two world wars, and into the modern day, with world peacekeeping operations under the aegis of NATO, the EU or the UN.

The Italian Army, Navy, Air Force, and Carabinieri collectively form the Italian Armed Forces, under the command of the High Council of Defence, presided over by the president, per the Constitution of Italy. According to Article 78, the Parliament has the authority to declare a state of war and vest the necessary war-making powers in the government.

Despite not being a branch of the armed forces, the Guardia di Finanza has military status and is organised along military lines.[e] Since 2005, military service has been voluntary.[176] In 2010, the Italian military had 293,202 personnel on active duty,[177] of which 114,778 are Carabinieri.[178] As part of NATO's nuclear sharing strategy, Italy hosts 90 US B61 nuclear bombs located at the Ghedi and Aviano air bases.[179]

The Army is the national ground defence force. It was formed in 1946, when Italy became a republic, from what remained of the "Royal Italian Army". Its best-known combat vehicles are the Dardo infantry fighting vehicle, the B1 Centauro tank destroyer, and the Ariete tank, and among its aircraft are the Mangusta attack helicopter, deployed on EU, NATO, and UN missions. It has at its disposal Leopard 1 and M113 armoured vehicles.

The Italian Navy is a blue-water navy. It was also formed in 1946 from what remained of the Regia Marina (the 'Royal Navy'). The Navy, being a member of the EU and NATO, has taken part in coalition peacekeeping operations around the world. In 2014, the Navy operated 154 vessels in service, including minor auxiliary vessels.[180]

The Italian Air Force was founded as an independent service arm in 1923 by King Victor Emmanuel III as the Regia Aeronautica ('Royal Air Force'). After World War II, it was renamed as the Regia Aeronautica. In 2021, the Italian Air Force operated 219 combat jets. A transport capability is guaranteed by a fleet of 27 C-130Js and C-27J Spartan. The acrobatic display team is the Frecce Tricolori ('Tricolour Arrows').

An autonomous corps of the military, the Carabinieri are the gendarmerie and military police of Italy, policing the military and civilian population alongside Italy's other police forces. While different branches of the Carabinieri report to separate ministries, the corps reports to the Ministry of Internal Affairs when maintaining public order and security.[181]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Italy is constituted of 20 regions (regioni), five of which have special autonomous status which enables them to enact legislation on additional matters.[182]

The regioni contain 107 provinces (province) or metropolitan cities (città metropolitane), and 7,896 municipalities (comuni).[182]

Economy

[edit]Italy has an advanced[183] mixed economy that is the third-largest in the eurozone and 11th-largest in the world by purchasing power parity-adjusted GDP.[7] It possesses the ninth-largest national wealth and ranks third in central bank gold reserves. As a founding member of the G7, the eurozone, and the OECD, it is one of the most industrialised countries and a major trading nation in Europe.[184] A developed country ranked 30th on the Human Development Index, it performs well in life expectancy, healthcare,[185] and education. Italy is well known for its creative and innovative businesses,[186] a competitive agricultural sector,[187] and its influential and high-quality automobile, machinery, food, design, and fashion industries.[188]

Italy is the world's eight-largest manufacturing country and the second-largest in Europe,[191] characterised by fewer multinational corporations than other economies of comparable size and many dynamic small- and medium-sized enterprises, clustered in industrial districts, which are the backbone of Italian industry. This has produced a niche-markets manufacturing sector often focused on the export of luxury products. While less capable of competing on quantity, it can compete with Asian economies that have lower labour costs through higher-quality products.[192] Italy was the world's 9th-largest exporter in 2023. Its closest trade ties are with other EU countries, and its largest export partners in 2019 were Germany (12%), France (11%), and the US (10%).[193]

The Italian automotive industry is a significant part of the country's manufacturing sector, with over 144,000 firms and almost 485,000 employees in 2015,[194] contributing 9% to GDP.[195][196] The country boasts a wide range of vehicles, from mass market-oriented brands such as Fiat and premium brands like Alfa Romeo and Maserati to luxury supercars such as Pagani, Lamborghini, and Ferrari.

The Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena is the world's oldest or second oldest bank in continuous operation, depending on the definition, and the fourth-largest Italian commercial and retail bank.[197] Italy has a strong cooperative sector with the largest share in the EU of the population (4.5%) employed by a cooperative.[198] The Val d'Agri area, Basilicata, hosts the largest onshore hydrocarbon field in Europe.[199] Moderate natural gas reserves, mainly in the Po Valley and offshore under the Adriatic, have been discovered and constitute the country's most important mineral resource. Italy is one of the world's leading producers of pumice, pozzolana, and feldspar.[200] Another notable resource is marble, especially the famous white Carrara marble from Tuscany.

Italy is part of a monetary union, the eurozone, which represents around 330 million citizens, and of the European single market, which represents more than 500 million consumers. Several domestic commercial policies are determined by agreements among EU members and EU legislation. Italy joined the common European currency, the euro, in 2002.[201] Its monetary policy is set by the European Central Bank.

Italy was hit by the 2008 financial crisis, which exacerbated structural problems.[202] After strong GDP growth of 5–6% per year from the 1950s to the early 1970s,[203] and a progressive slowdown in the 1980–90s, the country stagnated in the 2000s.[204] Political efforts to revive growth with massive government spending produced a severe rise in public debt, which stood at over 132% of GDP in 2017;[205] the second highest in the EU, after Greece.[206] The largest portion of Italian public debt is owned by national subjects, a major difference between Italy and Greece,[207] and the level of household debt is much lower than the OECD average.[208]

A gaping north–south divide is a major factor of socio-economic weakness;[209] there is a huge difference in official income between northern and southern regions and municipalities.[210] The richest province, Alto Adige-South Tyrol, earns 152% of the national GDP per capita, while the poorest region, Calabria, earns 61%.[211] The unemployment rate (11%) is above the eurozone average,[212] but the disaggregated figure is 7% in the north and 19% in the south.[213] The youth unemployment rate (32% in 2018) is extremely high.

Agriculture

[edit]According to the last agricultural census, there were 1.6 million farms in 2010 (−32% since 2000) covering 12,700,000 ha or 31,382,383 acres (63% are in south Italy).[215] 99% are family-operated and small, averaging only 8 ha (20 acres).[215] Of the area in agricultural use, grain fields take up 31%, olive orchards 8%, vineyards 5%, citrus orchards 4%, sugar beets 2%, and horticulture 2%. The remainder is primarily dedicated to pastures (26%) and feed grains (12%).[215]

Italy is the world's largest wine producer,[216][217] and a leading producer of olive oil, fruits (apples, olives, grapes, oranges, lemons, pears, apricots, hazelnuts, peaches, cherries, plums, strawberries, and kiwifruits), and vegetables (especially artichokes and tomatoes). The most famous Italian wines are the Tuscan Chianti and the Piedmontese Barolo. Other famous wines are Barbaresco, Barbera d'Asti, Brunello di Montalcino, Frascati, Montepulciano d'Abruzzo, Morellino di Scansano, and the sparkling wines Franciacorta and Prosecco.

Quality goods in which Italy specialises, particularly wines and regional cheeses, are often protected under the quality assurance labels DOC/DOP. This geographical indication certificate, accredited by the EU, is considered important to avoid confusion with ersatz goods.

Transport

[edit]

Italy was the first country to build motorways, the autostrade, reserved for fast traffic and motor vehicles.[218] In 2002 there were 668,721 km (415,524 mi) of serviceable roads in Italy, including 6,487 km (4,031 mi) of motorways, state-owned but privately operated by Atlantia. In 2005, about 34,667,000 cars (590 per 1,000 people) and 4,015,000 goods vehicles circulated on the network.[219]

The railway network, state-owned and operated by Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (FSI), in 2024 totalled 16,879 km (10,488 mi), of which 12,277 km (7,629 mi) is electrified[221], and on which 4,802 locomotives and railcars run. The main public operator of high-speed trains is Trenitalia, part of FSI. High-speed trains are in three categories: Frecciarossa ('red arrow') trains operate at a maximum 300 km/h on dedicated high-speed tracks; Frecciargento ('silver arrow') operate at a maximum 250 km/h on high-speed and mainline tracks; and Frecciabianca ('white arrow') operate on high-speed regional lines at a maximum 200 km/h. Italy has 11 rail border crossings over the Alpine mountains with neighbouring countries.

Italy is fifth in Europe by number of passengers using air transport, with about 148 million passengers, or about 10% of the European total in 2011.[222] In 2022, there were 45 civil airports, including the hubs of Milan Malpensa Airport and Rome Fiumicino Airport.[223] Since 2021, Italy's flag carrier has been ITA Airways, which took over from Alitalia.[224]

In 2004, there were 43 major seaports, including Genoa, the country's largest and second-largest in the Mediterranean. In 2005, Italy maintained a civilian air fleet of about 389,000 units and a merchant fleet of 581 ships.[219] The national inland waterways network had a length of 2,400 km (1,491 mi) for commercial traffic in 2012.[193] North Italian ports, such as the deep-water port of Trieste, with its extensive rail connections to Central and Eastern Europe, are the destination of subsidies and significant foreign investment.[225]

In August 2025, the planned Strait of Messina Bridge was given final approval by the Meloni government, with construction set to commence in the autumn of 2025. It will connect Calabria with Sicily when it opens in 2032, and it will become the longest suspension bridge in the world.[226]

Energy

[edit]

Italy has become one of the world's largest producers of renewable energy, ranking as the second largest producer in the EU and the ninth in the world. Wind power, hydroelectricity, and geothermal power are significant sources of electricity in the country. Renewable sources account for 28% of all electricity produced, with hydro alone reaching 13%, followed by solar at 6%, wind at 4%, bioenergy at 3.5%, and geothermal at 1.6%.[228] The rest of the national demand is supplied by fossil fuels (natural gas 38%, coal 13%, oil 8%) and imports.[228] Eni, operating in 79 countries, is one of the seven "Big Oil" companies, and one of the world's largest industrial companies.[229]

Solar energy production alone accounted for 9% of electricity in 2014, making Italy the country with the highest contribution from solar energy in the world.[227] The Montalto di Castro Photovoltaic Power Station, completed in 2010, is the largest photovoltaic (PV) power station in Italy.[230] Italy was the first country to exploit geothermal energy to produce electricity.[231] Nuclear power in Italy was abandoned after 1987 referendums (in the wake of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster), although Italy still imports nuclear energy from Italy-owned reactors in foreign territories.

Science and technology

[edit]

Through the centuries, Italy has fostered a scientific community that produced major discoveries the sciences. Galileo Galilei played a major role in the Scientific Revolution and is widely considered the father of observational astronomy,[232] modern physics,[233] and the scientific method.[234][235]

The Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso (LNGS) is the largest underground research centre in the world.[236] ELETTRA, Eurac Research, ESA Centre for Earth Observation, Institute for Scientific Interchange, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation, and the International Centre for Theoretical Physics conduct basic research. Trieste has the highest percentage of researchers in Europe, in relation to the population.[237] Italy was ranked 26th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[238] There are technology parks in Italy such as the Science and Technology Parks Kilometro Rosso (Bergamo), the AREA Science Park (Trieste), The VEGA-Venice Gateway for Science and Technology (Venezia), the Toscana Life Sciences (Siena), the Technology Park of Lodi Cluster (Lodi), and the Technology Park of Navacchio (Pisa),[239] as well as science museums such as the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci in Milan.

The north–south large difference in income leads to a "digital divide".[240][241]

Tourism

[edit]

People have visited Italy for centuries, yet the first to visit the peninsula for tourism were aristocrats during the Grand Tour, which began in the 17th century, and flourished in the 18th and the 19th centuries.[243] This was a period in which European aristocrats, many of whom were British, visited parts of Europe, with Italy as a key destination.[243] For Italy, this was in order to study ancient architecture, local culture, and admire its natural beauty.[244]

Italy is the fifth-most visited country, with a total of 57 million arrivals in 2024.[245] In 2014, the income from travel and tourism was EUR163 billion (10% of GDP) and 1,082,000 jobs were directly related to it (5% of employment).[246]

Tourist interest is mainly in culture, cuisine, history, architecture, art, religious sites and routes, wedding tourism, naturalistic beauties, nightlife, underwater sites, and spas.[247] Winter and summer tourism are present in locations in the Alps and the Apennines,[248] while seaside tourism is widespread among locations along the Mediterranean.[249] Italy is the leading cruise tourism destination in the Mediterranean.[250] Small, historical, and artistic villages are promoted through the association I Borghi più belli d'Italia (lit. 'The most beautiful villages of Italy').

The most visited regions are Veneto, Tuscany, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, and Lazio.[251] Rome is the third most visited city in Europe, and 12th in the world, with 9.4 million arrivals in 2017.[252] Venice and Florence are among the world's top 100 destinations.

Italy has the most World Heritage Sites of any country: 61,[253] of which 55 are cultural and 6 natural.[254]

Demographics

[edit]

As of 2025, Italy has 58,934,177 inhabitants.[6] Its population density of 195 inhabitants per square kilometre (510/sq mi) is higher than most Western European countries. However, distribution is uneven: the most densely populated areas are the Po Valley (almost half the population) and the metropolitan areas of Rome and Naples, while vast regions such as the Alps and Apennine highlands, the plateaus of Basilicata, and the island of Sardinia, as well as much of Sicily, are sparsely populated.

Italy's population almost doubled during the 20th century, but the pattern of growth was uneven because of large-scale internal migration from the rural south to the industrial north, a consequence of the Italian economic miracle of the 1950–1960s. High fertility rates persisted until the 1970s, after which they started to decline; the total fertility rate (TFR) reached an all-time low of 1.2 children per woman in 1995, well below the replacement rate of 2.1 and considerably below the high of 5 in 1883.[255] Since 2008, when the rate climbed slightly to 1.4,[256][257] the number of births has consistently declined every year, reaching a record low of 379,000 in 2023 – the fewest since 1861.[258] In 2024, it stood at 1.2.[259]

As a result of these trends, Italy's population is rapidly aging and gradually shrinking. Nearly one in four Italians is over 65,[258] and the country has the fourth oldest population in the world, with a median age of 48 and an average age of 46.6.[193][260] The overall population has been falling steadily since 2014 and is estimated to have fallen just below 59 million in 2024, representing a cumulative loss of more than 1.36 million people in one decade.[261]

From the late 19th century to the 1960s, Italy was a country of mass emigration. Between 1898 and 1914, the peak years of Italian diaspora, approximately 750,000 Italians emigrated annually.[262] The diaspora included more than 25 million Italians and is considered the greatest mass migration of recent times.[263]

Largest cities

[edit]| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rome | Lazio | 2,746,984 | 11 | Verona | Veneto | 255,133 | ||

| 2 | Milan | Lombardy | 1,366,155 | 12 | Venice | Veneto | 249,466 | ||

| 3 | Naples | Campania | 908,082 | 13 | Messina | Sicily | 216,918 | ||

| 4 | Turin | Piedmont | 856,745 | 14 | Padua | Veneto | 207,694 | ||

| 5 | Palermo | Sicily | 625,956 | 15 | Brescia | Lombardy | 199,949 | ||

| 6 | Genoa | Liguria | 563,947 | 16 | Parma | Emilia-Romagna | 198,986 | ||

| 7 | Bologna | Emilia-Romagna | 390,734 | 17 | Trieste | Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 198,668 | ||

| 8 | Florence | Tuscany | 362,353 | 18 | Prato | Tuscany | 198,326 | ||

| 9 | Bari | Apulia | 315,473 | 19 | Taranto | Apulia | 185,909 | ||

| 10 | Catania | Sicily | 297,517 | 20 | Modena | Emilia-Romagna | 184,739 | ||

Immigration

[edit]

In the 1980s, until then a linguistically and culturally homogeneous society, Italy began to attract substantial flows of immigrants.[265] After the fall of the Berlin Wall and of the Iron Curtain, waves of migration originated from many former socialist countries of East Europe. The EU enlarged in 2004, in 2007 (Romania and Bulgaria) and in 2013 (Croatia).

Other sources of immigration have been neighbouring North Africa, the Asia-Pacific region[266], the Philippines and Latin America.

In 2010, the foreign-born population was from the following regions: Europe (54%), Africa (22%), Asia (16%), the Americas (8%), and Oceania (0.06%). The distribution of the foreign population is geographically varied: in 2020, 61% of foreign citizens lived in the north, 24% in the centre, 11% in the south, and 4% on the islands.[267]

In 2021, Italy had about 5.2 million foreign residents,[1][268] making up 9% of the population. The figures include more than half a million children born in Italy to foreign nationals, but exclude foreign nationals who have subsequently acquired Italian citizenship;[269] in 2016, about 201,000 people became Italian citizens.[270] The official figures also do not include illegal immigrants, which was estimated to be 670,000 in 2008.[271] About one million Romanian citizens are registered as living in Italy, representing the largest migrant population.

Languages

[edit]

Italy's official language is Italian.[272][273] There are an estimated 64 million native Italian speakers around the world,[274] and another 21 million use it as a second language.[275] Italian is often natively spoken as a regional dialect, not to be confused with Italy's regional and minority languages;[276] however, during the 20th century, the establishment of a national education system led to a decrease in regional dialects. Standardisation was further expanded in the 1950s and 1960s, due to economic growth and the rise of mass media and television.

Twelve "historical minority languages" are formally recognised: Albanian, Catalan, German, Greek, Slovene, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan, and Sardinian.[272] Four of these enjoy co-official status in their respective regions: French in the Aosta Valley;[277] German in South Tyrol, and Ladin as well in some parts of the same province and in parts of the neighbouring Trentino;[278] and Slovene in the provinces of Trieste, Gorizia, and Udine.[279] Other Ethnologue, ISO, and UNESCO languages are not recognised under Italian law. Like France, Italy has signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, but has not ratified it.[280][281]

Due to recent immigration, Italy has sizeable populations whose native language is not Italian, nor a regional language. According to the Italian National Institute of Statistics, in 2012 Romanian was the most common mother tongue among foreign residents: almost 800,000 people speak Romanian as their first language (22% of foreign residents aged 6 and over). Other prevalent mother tongues were Arabic (spoken by over 475,000; 13% of foreign residents), Albanian (380,000), and Spanish (255,000).[282]

Religion

[edit]

The Holy See, the episcopal jurisdiction of Rome, contains the government of Vatican City and the worldwide Catholic Church. It is recognised as a sovereign entity, headed by the pope, who is also the Bishop of Rome, with which diplomatic relations can be maintained.[283] [f]

Italy has historically been dominated by Catholicism.[284] Most Catholics are nominal; Associated Press described Italian Catholicism as "nominally embraced but rarely lived".[284] Around 2010, Italy had the world's fifth-largest Catholic population and the largest in Europe.[285][286] Since 1985, Catholicism is no longer the State religion.[287]

In 2011, minority Christian faiths included an estimated 1.5 million Orthodox Christians, while Protestantism has been growing.[288] Italy has for centuries welcomed Jews expelled from other countries, notably Spain. However, about 20% of Italian Jews were killed during the Holocaust.[289] This, together with emigration before and after World War II, has left around 28,000 Jews.[290] There are 120,000 Hindus[291] and 70,000 Sikhs.[292]

The state devolves shares of income tax to recognised religious communities, under a regime known as eight per thousand. Donations are allowed to Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, and Hindu communities; however, Islam remains excluded, as no Muslim communities have signed a concordat.[293] Taxpayers who do not wish to fund a religion contribute their share to the welfare system.[294]

Education

[edit]

Education is mandatory and free from ages six to sixteen,[295] and consists of five stages: kindergarten, primary school, lower secondary school, upper secondary school, and university.[296]

Primary school lasts eight years. Students are given a basic education in Italian, English, mathematics, natural sciences, history, geography, social studies, physical education, and visual and musical arts. Secondary school lasts for five years and includes three traditional types of schools focused on different academic levels: the liceo prepares students for university studies with a classical or scientific curriculum, while the istituto tecnico and the istituto professionale prepare pupils for vocations.

In 2018, secondary education was evaluated as being below the average among OECD countries.[297] Italy scored below the OECD average in reading and science, and near the OECD average in mathematics.[297] A wide gap exists between northern schools, which perform near average, and the south, which had much poorer results.[298]

Tertiary education is divided between public universities, private universities, and the prestigious and selective superior graduate schools, such as the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. 33 Italian universities were ranked among the world's top 500 in 2019.[299] Bologna University, founded in 1088, is the oldest university still in operation,[300] and one of the leading academic institutions in Europe.[301] Bocconi University, the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, LUISS, the Polytechnic University of Turin, the Polytechnic University of Milan, the Sapienza University of Rome, and the University of Milan are also ranked among the best.[302]

Health

[edit]

Italy's life expectancy in 2015 was 80.5 years for men and 84.8 for women, placing the country 5th in the world.[304] Compared to other Western countries, Italy has a low rate of adult obesity (below 10%[305]), as the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet are very significant.[306] In 2013, UNESCO, prompted by Italy, added the Mediterranean diet to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of Italy, Morocco, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, and Croatia.[307]

The proportion of daily smokers was 22% in 2012, down from 24% in 2000 but above the OECD average.[308] Since 2005, smoking in public places has been restricted to "specially ventilated rooms".[309]

Since 1978, the state has run a universal public healthcare system.[310] However, healthcare is provided to all citizens and residents by a mixed public-private system. The public part is the Servizio Sanitario Nazionale, which is organised under the Ministry of Health and administered on a devolved regional basis. Healthcare spending accounted for 10% of GDP in 2020. Italy's healthcare system has been consistently ranked among the best in the world;[311] according to research by the World Health Organization (WHO) dating back to 2000, Italy had the second best healthcare system in the world in terms of spending efficiency and access to public care for citizens, after France.[312]

Culture

[edit]Italy is one of the primary birthplaces of Western civilisation and a cultural superpower.[313] Its culture has been shaped by a multitude of regional customs and local centres of power and patronage.[314] The country has made substantial contributions to the cultural and historical heritage of Europe.[315]

Architecture

[edit]

Italy is known for its architectural achievements,[318] such as the construction of arches, domes, and similar structures by ancient Rome, the founding of the Renaissance architectural movement in the late 14th to 16th centuries, and as the home of Palladianism, a style that inspired movements such as Neoclassical architecture and influenced designs of country houses all over the world, notably in the UK and US during the late 17th to early 20th centuries.

The first to begin a recognised sequence of designs were the Greeks and the Etruscans, progressing to classical Roman,[319] then the revival of the classical Roman era during the Renaissance, and evolving into the Baroque era. The Christian concept of the basilica, a style that came to dominate in the Middle Ages, was invented in Rome.[320] Romanesque architecture, which flourished from approximately 800 to 1100 AD, was one of the most fruitful and creative periods in Italian architecture, when masterpieces, such as the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan, were built. It was known for its usage of Roman arches, stained glass windows, and curved columns. The main innovation of Italian Romanesque architecture was the vault, which had never been seen in Western architecture.[321]

Italian architecture significantly evolved during the Renaissance. Filippo Brunelleschi contributed to architectural design with his dome for the Cathedral of Florence, a feat of engineering not seen since antiquity.[322] A popular achievement of Italian Renaissance architecture was St. Peter's Basilica, designed by Donato Bramante in the early 16th century. Andrea Palladio influenced architects throughout Western Europe with the villas and palaces he designed.[323]

The Baroque period produced outstanding Italian architects. The most original work of late Baroque and Rococo architecture is the Palazzina di caccia of Stupinigi.[324] In 1752, Luigi Vanvitelli began the construction of the Royal Palace of Caserta.[325] In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Italy was influenced by the Neoclassical architectural movement. Villas, palaces, gardens, interiors, and art began again to be based on ancient Roman and Greek themes.[326]

During the Fascist period, the supposedly "Novecento movement" flourished, based on the rediscovery of imperial Rome. Marcello Piacentini, responsible for the urban transformations of cities, devised a form of simplified Neoclassicism.[327]

Visual art

[edit]

The history of Italian visual arts is significant to Western painting. Roman art was influenced by Greece and can be taken as a descendant of ancient Greek painting. The only surviving Roman paintings are wall paintings.[328] These may contain the first examples of trompe-l'œil, pseudo-perspective, and pure landscape.[329]

The Italian Renaissance is considered to be the golden age of painting, spanning from the 14th through the mid-17th centuries and having significant influence outside Italy. Artists such as Masaccio, Filippo Lippi, Tintoretto, Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian took painting to a higher level through the use of perspective. Michelangelo was also active as a sculptor; his works include masterpieces such as David, Pietà, and Moses.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the High Renaissance gave rise to a stylised art known as Mannerism. In place of the balanced compositions and rational approach to perspective that characterised art at the dawn of the 16th century, the Mannerists sought instability, artifice, and doubt. The unperturbed faces and gestures of Piero della Francesca and the calm Virgins of Raphael were replaced by the troubled expressions of Pontormo and emotional intensity of El Greco.

In the 17th century, among the greatest painters of Italian Baroque are Caravaggio, Artemisia Gentileschi, Carlo Saraceni, and Bartolomeo Manfredi. In the 18th century, Italian Rococo was mainly inspired by French Rococo. Italian Neoclassical sculpture focused, with Antonio Canova's nudes, on the idealist aspect of the movement.

In the 19th century, Romantic painters included Francesco Hayez and Francesco Podesti. Impressionism was brought from France to Italy by the Macchiaioli, and realism by Gioacchino Toma and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo. In the 20th century, with futurism, Italy rose again as a seminal country for evolution in painting and sculpture. Futurism was succeeded by the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, who exerted an influence on the surrealists.[330]

Literature

[edit]Formal Latin literature began in 240 BC, when the first stage play was performed in Rome.[331] Latin literature was, and is, highly influential, with numerous writers, poets, philosophers, and historians, such as Pliny the Elder, Pliny the Younger, Virgil, Horace, Propertius, Ovid, and Livy. The Romans were famous for their oral tradition, poetry, drama, and epigrams.[332] In the early 13th century, Francis of Assisi was the first Italian poet, with his religious song Canticle of the Sun.[333]

At the court of Emperor Frederick II in Sicily, in the 13th century, lyrics modelled on Provençal forms and themes were written in a refined version of the local vernacular. One of these poets was Giacomo da Lentini, inventor of the sonnet form; the most famous early sonneteer was Petrarch.[334]

Guido Guinizelli is the founder of the Dolce Stil Novo, a school that added a philosophical dimension to love poetry. This new understanding of love, expressed in a smooth style, influenced the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, who established the basis of modern Italian. Dante's work, Divine Comedy, is among the finest in literature.[335] Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio sought and imitated the works of antiquity and cultivated their own artistic personalities. Petrarch achieved fame through his collection of poems, Il Canzoniere. Equally influential was Boccaccio's The Decameron, a very popular collection of short stories.[336]

Renaissance authors' works include Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince, an essay on political science in which the "effectual truth" is taken to be more important than any abstract ideal. Giovanni Francesco Straparola and Giambattista Basile, who wrote The Facetious Nights of Straparola (1550–55) and the Pentamerone (1634), respectively, printed some of the first known versions of fairy tales in Europe.[337] The Baroque period produced the clear scientific prose of Galileo. In the 17th century, the Arcadians began a movement to restore simplicity and classical restraint to poetry.[338]

Italian writers embraced Romanticism in the 19th century; it coincided with ideas of the Risorgimento, the movement that brought Italian unification. Unification was heralded by the poets Vittorio Alfieri, Ugo Foscolo, and Giacomo Leopardi. Works by Alessandro Manzoni, the leading Italian Romantic, are a symbol of Italian unification for their patriotic message and because of his efforts in the development of modern, unified Italian.[339]

In the late 19th century, a literary movement called verismo, which extolled realism, played a major role in Italian literature. Emilio Salgari, a writer of action-adventure swashbucklers and a pioneer of science fiction, published his Sandokan series.[340] In 1883, Carlo Collodi published The Adventures of Pinocchio, which became the most celebrated children's classic by an Italian author and one of the world's most translated non-religious books.[341] A movement called futurism influenced literature in the early 20th century. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote Manifesto of Futurism and called for the use of language and metaphors that glorified the speed, dynamism, and violence of the machine age.[342]