Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Arabs

View on Wikipedia

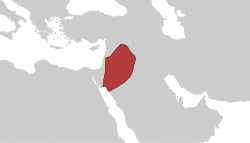

Arabs (Arabic: عَرَب)[d] are an ethnic group[e] mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.[74]

Key Information

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years.[75] In the 9th century BCE, the Assyrians made written references to Arabs as inhabitants of the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Arabia.[76] Throughout the Ancient Near East, Arabs established influential civilizations starting from 3000 BCE onwards, such as Dilmun, Gerrha, and Magan, playing a vital role in trade between Mesopotamia, and the Mediterranean.[77] Other prominent tribes include Midian,[clarification needed] ʿĀd, and Thamud mentioned in the Bible and Quran. Later, in 900 BCE, the Qedarites enjoyed close relations with the nearby Canaanite and Aramaean states, and their territory extended from Lower Egypt to the Southern Levant.[78] From 1200 BCE to 110 BCE, powerful kingdoms emerged such as Saba, Lihyan, Minaean, Qataban, Hadhramaut, Awsan, and Homerite emerged in Arabia.[79] According to the Abrahamic tradition, Arabs are descendants of Abraham through his son Ishmael.[80]

During classical antiquity, the Nabataeans established their kingdom with Petra as the capital in 300 BCE,[81] by 271 CE, the Palmyrene Empire with the capital Palmyra, led by Queen Zenobia, encompassed the Syria Palaestina, Arabia Petraea, Egypt, and large parts of Anatolia.[82] The Arab or Aramean Itureans inhabited Lebanon, Syria, and northern Palestine (Galilee) during the Hellenistic and Roman periods.[83] The Osroene and Hatran were Arab-ruled kingdoms in Upper Mesopotamia around 200 CE.[84] In 164 CE, the Sasanians called part of upper Mesopotamia "Arbayistan", meaning "land of the Arabs,"[85] having conquered the land from the previously Jewish Adiabene.[86] The probably Arab Emesenes ruled Emesa (Homs), Syria by 46 BCE.[87] During late antiquity, the Tanukhids, Salihids, Lakhmids, Kinda, and Ghassanids were dominant Arab tribes in the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Arabia, they predominantly embraced Christianity.[88]

During the Middle Ages, Islam fostered a vast Arab union, leading to significant Arab migrations to the Maghreb, the Levant, and neighbouring territories under the rule of Arab empires such as the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid, ultimately leading to the decline of the Byzantine and Sasanian empires. At its peak, Arab territories stretched from southern France to western China, forming one of history's largest empires.[89] The Great Arab Revolt in the early 20th century aided in dismantling the Ottoman Empire, ultimately leading to the formation of the Arab League on 22 March 1945, with its Charter endorsing the principle of a "unified Arab homeland".[90]

Arabs from Morocco to Iraq share a common bond based on ethnicity, language, culture, history, identity, ancestry, nationalism, geography, unity, and politics,[91] which give the region a distinct identity and distinguish it from other parts of the Muslim world.[92] They also have their own customs, literature, music, dance, media, food, clothing, society, sports, architecture, art and, mythology.[93] Arabs have significantly influenced and contributed to human progress in many fields, including science, technology, philosophy, ethics, literature, politics, business, art, music, comedy, theatre, cinema, architecture, food, medicine, and religion.[94] Before Islam, most Arabs followed polytheistic Semitic religion, while some tribes adopted Judaism or Christianity and a few individuals, known as the hanifs, followed a form of monotheism.[95] Currently, around 93% of Arabs are Muslims, while the rest are mainly Arab Christians, as well as Arab groups of Druze and Baháʼís.[96]

Etymology

[edit]

The earliest documented use of the word Arab in reference to a people appears in the Kurkh Monoliths, an Akkadian-language record of the Assyrian conquest of Aram (9th century BCE). The Monoliths used the term to refer to Bedouins of the Arabian Peninsula under King Gindibu, who fought as part of a coalition opposed to Assyria.[97]

The related word ʾaʿrāb is used to refer to Bedouins today, in contrast to ʿArab which refers to Arabs in general.[98] Both terms are mentioned around 40 times in pre-Islamic Sabaean inscriptions. The term ʿarab ('Arab') occurs also in the titles of the Himyarite kings from the time of 'Abu Karab Asad until MadiKarib Ya'fur. According to Sabaean grammar, the term ʾaʿrāb is derived from the term ʿarab. The term is also mentioned in Quranic verses, referring to people who were living in Madina and it might be a south Arabian loanword into Quranic language.[99]

The oldest surviving indication of an Arab national identity is an inscription made in an archaic form of Arabic in 328 CE using the Nabataean alphabet, which refers to Imru' al-Qays ibn 'Amr as 'King of all the Arabs'.[100][101] Herodotus refers to the Arabs in the Sinai, southern Palestine, and the frankincense region (Southern Arabia). Other Ancient-Greek historians like Agatharchides, Diodorus Siculus and Strabo mention Arabs living in Mesopotamia (along the Euphrates), in Egypt (the Sinai and the Red Sea), southern Jordan (the Nabataeans), the Syrian steppe and in eastern Arabia (the people of Gerrha). Inscriptions dating to the 6th century BCE in Yemen include the term 'Arab'.[102]

The most popular Arab account holds that the word Arab came from an eponymous father named Ya'rub, who was supposedly the first to speak Arabic. Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani had another view; he states that Arabs were called gharab ('westerners') by Mesopotamians because Bedouins originally resided to the west of Mesopotamia; the term was then corrupted into Arab.[citation needed]

Yet another view is held by al-Masudi that the word Arab was initially applied to the Ishmaelites of the Arabah valley. In Biblical etymology, Arab (Hebrew: arvi) comes from the desert origin of the Bedouins it originally described (arava means 'wilderness').[citation needed]

The root ʿ-r-b has several additional meanings in Semitic languages—including 'west, sunset', 'desert', 'mingle', 'mixed', 'merchant' and 'raven'—and are "comprehensible" with all of these having varying degrees of relevance to the emergence of the name. It is also possible that some forms were metathetical from ʿ-B-R, 'moving around' (Arabic: ʿ-B-R, 'traverse') and hence, it is alleged, 'nomadic'.[103]

Origins

[edit]

Arabic is a Semitic language that belongs to the Afroasiatic language family. The majority of scholars accept the "Arabian Peninsula" has long been accepted as the original Urheimat (linguistic homeland) of the Semitic languages.[104][105][106][107] with some scholars investigating if its origins are in the Levant.[108] The ancient Semitic-speaking peoples lived in the ancient Near East, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian Peninsula from the 3rd millennium BCE to the end of antiquity. Proto-Semitic likely reached the Arabian Peninsula by the 4th millennium BCE, and its daughter languages spread outward from there,[109] while Old Arabic began to differentiate from Central Semitic by the start of the 1st millennium BCE.[110] Central Semitic is a branch of the Semitic language includes Arabic, Aramaic, the Canaanite languages (Ammonite, Hebrew, Moabite, Philistine, Phoenician, etc.) and others.[111][112] The origins of Proto-Semitic may lie in the Arabian Peninsula, with the language spreading from there to other regions. This theory proposes that Semitic peoples reached Mesopotamia and other areas from the deserts to the west, such as the Akkadians who entered Mesopotamia around the late 4th millennium BCE.[109] The origins of Semitic peoples are thought to include various regions Mesopotamia, the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa. Some view that Semitic may have originated in the Levant around 3800 BCE and subsequently spread to the Horn of Africa around 800 BCE from Arabia, as well as to North Africa.[113][114]

According to Arab–Islamic–Jewish traditions, Ishmael, the son of Abraham and Hagar was "father of the Arabs".[115][116][117][118][119] Ishmael was considered the ancestor of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the founder of Islam. The tribes of Central West Arabia called themselves the "people of Abraham and the offspring of Ishmael."[120] Ibn Khaldun, an Arab scholar in the 8th century, described the Arabs as having Ishmaelite origins.[121]

The Quran mentions that Ibrahim (Abraham) and his wife Hajar (Hagar) bore a prophetic child named Ishmael, who was gifted by God a favor above other nations.[122] Ibrahim and Ishmael built the Kaaba in Mecca, which was originally constructed by Adam.[123] According to the Samaritan book Asaṭīr:[124]: 262 "And after the death of Abraham, Ishmael reigned twenty-seven years; And all the children of Nebaot ruled for one year in the lifetime of Ishmael; And for thirty years after his death from the river of Egypt to the river Euphrates; and they built Mecca."[125] The Targum Onkelos annotates (Genesis 25:16), describing the extent of their settlements: The Ishmaelites lived from Hindekaia (India) to Chalutsa (possibly in Arabia), by the side of Mizraim (Egypt), and from the area around Arthur (Assyria) up towards the north. This description suggests that the Ishmaelites were a widely dispersed group with a presence across a significant portion of the ancient Near East.[126][127]

History

[edit]The nomads of Arabia had been spreading through the desert fringes of the Fertile Crescent since at least 3000 BCE, but the first known reference to the Arabs as a distinct group is from an Assyrian scribe recording the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BCE.[128][129] The history of the Arabs during the pre-Islamic period covers various regions such as Arabia, Levant, Mesopotamia, and Egypt. The Arabs were mentioned by their neighbors, such as Assyrian and Babylonian Royal Inscriptions from 9th to 6th century BCE.[130][131][132][133] There are also records from Sargon's reign that mention sellers of iron to people called Arabs in Ḫuzaza in Babylon, causing Sargon to prohibit such trade out of fear that the Arabs might use the resource to manufacture weapons against the Assyrian army. The history of the Arabs in relation to the Bible shows that they were a significant part of the region and played a role in the lives of the Israelites. The study asserts that the Arab nation is an ancient and significant entity; however, it highlights that the Arabs lacked a collective awareness of their unity. They did not inscribe their identity as Arabs or assert exclusive ownership over specific territories.[134]

Magan, Midian, and ʿĀd are all ancient tribes or civilizations that are mentioned in Arabic literature and have roots in the Arabia. Magan (Arabic: مِجَانُ, Majan), known for its production of copper and other metals, the region was an important trading center in ancient times and is mentioned in the Qur'an as a place where Musa (Moses) traveled during his lifetime.[135][136] Midian (Arabic: مَدْيَن, Madyan), on the other hand, was a region located in the northwestern part of the Arabia, the people of Midian are mentioned in the Qur'an as having worshiped idols and having been punished by God for their disobedience.[137][138] Moses also lived in Midian for a time, where he married and worked as a shepherd. ʿĀd (Arabic: عَادَ, ʿĀd), as mentioned earlier, was an ancient tribe that lived in the southern Arabia, the tribe was known for its wealth, power, and advanced technology, but they were ultimately destroyed by a powerful windstorm as punishment for their disobedience to God.[139] ʿĀd is regarded as one of the original Arab tribes.[140][141] The historian Herodotus provided extensive information about Arabia, describing the spices, terrain, folklore, trade, clothing, and weapons of the Arabs. In his third book, he mentioned the Arabs as a force to be reckoned with in the north of the Arabian Peninsula just before Cambyses' campaign against Egypt. Other Greek and Latin authors who wrote about Arabia include Theophrastus, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Pliny the Elder. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus wrote about the Arabs and their king, mentioning their relationship with Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt. The tribute paid by the Arab king to Cleopatra was collected by Herod, the king of the Jews, but the Arab king later became slow in his payments and refused to pay without further deductions.[142] Geshem the Arab was an Arab man who opposed Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible (Neh. 2:19, 6:1). He was likely the chief of the Arab tribe "Gushamu" and have been a powerful ruler with influence stretching from northern Arabia to Judah. The Arabs and the Samaritans made efforts to hinder Nehemiah's rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem.[143][144][145]

The term "Saracens" was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the "Arabs" who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Petraea (Levant) and Arabia Deserta (Arabia).[146][147] The Christians of Iberia used the term Moor to describe all the Arabs and Muslims of that time. Arabs of Medina referred to the nomadic tribes of the deserts as the A'raab, and considered themselves sedentary, but were aware of their close racial bonds. Hagarenes is a term widely used by early Syriac, Greek, and Armenian to describe the early Arab conquerors of Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt, refers to the descendants of Hagar, who bore a son named Ishmael to Abraham in the Old Testament. In the Bible, the Hagarenes referred to as "Ishmaelites" or "Arabs."[148] The Arab conquests in the 7th century was a sudden and dramatic conquest led by Arab armies, which quickly conquered much of the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain. It was a significant moment for Islam, which saw itself as the successor of Judaism and Christianity.[149]

Antiquity

[edit]

Limited local historical coverage of these civilizations means that archaeological evidence, foreign accounts and Arab oral traditions are largely relied on to reconstruct this period. Prominent civilizations at the time included, Dilmun civilization was an important trading centre[152] which at the height of its power controlled the Arabian Gulf trading routes.[152] The Sumerians regarded Dilmun as holy land.[153] Dilmun is regarded as one of the oldest ancient civilizations in the Middle East.[154][155] which arose around the 4th millennium BCE and lasted to 538 BCE. Gerrha was an ancient city of Eastern Arabia, on the west side of the Gulf, Gerrha was the center of an Arab kingdom from approximately 650 BCE to circa CE 300. Thamud, which arose around the 1st millennium BCE and lasted to about 300 CE. From the beginning of the first millennium BCE, Proto-Arabic, or Ancient North Arabian, texts give a clearer picture of the Arabs' emergence. The earliest are written in variants of epigraphic south Arabian musnad script, including the 8th century BCE Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, the Thamudic texts found throughout the Arabian Peninsula and Sinai.

The Qedarites were a largely nomadic ancient Arab tribal confederation centred in the Wādī Sirḥān in the Syrian Desert. They were known for their nomadic lifestyle and for their role in the caravan trade that linked the Arabian Peninsula with the Mediterranean world. The Qedarites gradually expanded their territory over the course of the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, and by the 6th century BCE, they had consolidated into a kingdom that covered a large area in northern Arabia, southern Palestine, and the Sinai Peninsula. The Qedarites were influential in the ancient Near East, and their kingdom played a significant role in the political and economic affairs of the region for several centuries.[156]

Sheba (Arabic: سَبَأٌ Saba) is kingdom mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the Quran, though Sabaean was a South Arabian languaged and not an Arabic one. Sheba features in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian traditions, whose lineage goes back to Qahtan son of Hud, one of the ancestors of the Arabs,[157][158][159] Sheba was mentioned in Assyrian inscriptions and in the writings of Greek and Roman writers.[160] One of the ancient written references that also spoke of Sheba is the Old Testament, which stated that the people of Sheba supplied Syria and Egypt with incense, especially frankincense, and exported gold and precious stones to them.[161]

Sabaeans are mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. In the Quran,[162] they are described as either Sabaʾ (سَبَأ, not to be confused with Ṣābiʾ, صَابِئ),[158][159] or as Qawm Tubbaʿ (Arabic: قَوْم تُبَّع, lit. 'People of Tubbaʿ').[163][164] They were known for their prosperous trade and agricultural economy, which was based on the cultivation of frankincense and myrrh. These highly valued aromatic resins were exported to Egypt, Greece, and Rome, making the Sabaeans wealthy and powerful, they also traded in spices, textiles, and other luxury goods. The Maʾrib Dam was one of the greatest engineering achievements of the ancient world, and it provided water for the city of Maʾrib and the surrounding agricultural lands.[165][166][160]

Lihyan also called Dadān or Dedan was a powerful and highly organized ancient Arab kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula and used Dadanitic language.[167] The Lihyanites were known for their advanced organization and governance, and they played a significant role in the cultural and economic life of the region. The kingdom was centered around the city of Dedan (modern-day Al Ula), and it controlled a large territory that extended from Yathrib in the south to parts of the Levant in the north.[168][167] The Arab genealogies consider the Banu Lihyan to be Ishmaelites, and used Dadanitic language.[169]

The Kingdom of Ma'in was an ancient Arab kingdom with a hereditary monarchy system and a focus on agriculture and trade.[170] Proposed dates range from the 15th century BCE to the 1st century CE Its history has been recorded through inscriptions and classical Greek and Roman books, although the exact start and end dates of the kingdom are still debated. The Ma'in people had a local governance system with councils called "Mazood," and each city had its own temple that housed one or more gods. They also adopted the Phoenician alphabet and used it to write their language. The kingdom eventually fell to the Arab Sabaean people.[171][172]

Qataban was an ancient kingdom located in the South Arabia, which existed from the early 1st millennium BCE till the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.[174][174][175] It developed into a centralized state in the 6th century BCE with two co-kings ruling poles.[174][176] Qataban expanded its territory, including the conquest of Ma'in and successful campaigns against the Sabaeans.[175][173][177] It challenged the supremacy of the Sabaeans in the region and waged a successful war against Hadramawt in the 3rd century BCE.[173][178] Qataban's power declined in the following centuries, leading to its annexation by Hadramawt and Ḥimyar in the 1st century CE.[179][175][173][174][180][173]

The Kingdom of Hadhramaut it was known for its rich cultural heritage, as well as its strategic location along important trade routes that connected the Middle East, South Asia, and East Africa.[181] The Kingdom was established around the 3rd century BCE, and it reached its peak during the 2nd century CE, when it controlled much of the southern Arabian Peninsula. The kingdom was known for its impressive architecture, particularly its distinctive towers, which were used as watchtowers, defensive structures, and homes for wealthy families.[182] The people of Hadhramaut were skilled in agriculture, especially in growing frankincense and myrrh. They had a strong maritime culture and traded with India, East Africa, and Southeast Asia.[183] Although the kingdom declined in the 4th century, Hadhramaut remained a cultural and economic center. Its legacy can still be seen today.[184]

The ancient Kingdom of Awsān (8th–7th century BCE) was indeed one of the most important small kingdoms of South Arabia, and its capital Ḥajar Yaḥirr was a significant center of trade and commerce in the ancient world. The destruction of the city in the 7th century BCE by the king and Mukarrib of Saba' Karab El Watar is a significant event in the history of South Arabia. The victory of the Sabaeans over Awsān is also a testament to the military might and strategic prowess of the Sabaeans, who were one of the most powerful and influential kingdoms in the region.[185]

The Himyarite Kingdom or Himyar, was an ancient kingdom that existed from around the 2nd century BCE to the 6th century CE. It was centered in the city of Zafar, which is located in present-day Yemen. The Himyarites were an Arab people who spoke a South Arabian language and were known for their prowess in trade and seafaring,[186] they controlled the southern part of Arabia and had a prosperous economy based on agriculture, commerce, and maritime trade, they were skilled in irrigation and terracing, which allowed them to cultivate crops in the arid environment. The Himyarites converted to Judaism in the 4th century CE, and their rulers became known as the "Kings of the Jews", this conversion was likely influenced by their trade connections with the Jewish communities of the Red Sea region and the Levant, however, the Himyarites also tolerated other religions, including Christianity and the local pagan religions.[186]

Classical antiquity

[edit]The Nabataeans were nomadic Arabs who settled in a territory centred around their capital of Petra in what is now Jordan.[187][188] Their early inscriptions were in Aramaic, but gradually switched to Arabic, and since they had writing, it was they who made the first inscriptions in Arabic. The Nabataean alphabet was adopted by Arabs to the south, and evolved into modern Arabic script around the 4th century. This is attested by Safaitic inscriptions (beginning in the 1st century BCE) and the many Arabic personal names in Nabataean inscriptions. From about the 2nd century BCE, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Faw reveal a dialect no longer considered proto-Arabic, but pre-classical Arabic. Five Syriac inscriptions mentioning Arabs have been found at Sumatar Harabesi, one of which dates to the 2nd century CE.[189][190]

Arabs are first recorded in Palmyra in the late first millennium BCE.[191] The soldiers of the sheikh Zabdibel, who aided the Seleucids in the battle of Raphia (217 BCE), were described as Arabs; Zabdibel and his men were not actually identified as Palmyrenes in the texts, but the name "Zabdibel" is a Palmyrene name leading to the conclusion that the sheikh hailed from Palmyra.[192] After the Battle of Edessa in 260 CE. Valerian's capture by the Sassanian king Shapur I was a significant blow to Rome, and it left the empire vulnerable to further attacks. Zenobia was able to capture most of the Near East, including Egypt and parts of Asia Minor. However, their empire was short-lived, as Aurelian was able to defeat the Palmyrenes and recover the lost territories. The Palmyrenes were helped by their Arab allies, but Aurelian was also able to leverage his own alliances to defeat Zenobia and her army. Ultimately, the Palmyrene Empire lasted only a few years, but it had a significant impact on the history of the Roman Empire and the Near East.

Most scholars identify the Itureans as an Arab people who inhabited the region of Iturea,[193][194][195][196] emerged as a prominent power in the region after the decline of the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd century BCE, from their base around Mount Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley, they came to dominate vast stretches of Syrian territory,[197] and appear to have penetrated into northern parts of Palestine as far as the Galilee.[83] Tanukhids were an Arab tribal confederation that lived in the central and eastern Arabian Peninsula during the late ancient and early medieval periods. As mentioned earlier, they were a branch of the Rabi'ah tribe, which was one of the largest Arab tribes in the pre-Islamic period. They were known for their military prowess and played a significant role in the early Islamic period, fighting in battles against the Byzantine and Sassanian empires and contributing to the expansion of the Arab empire.[198]

The Osroene Arabs, also known as the Abgarids,[199][200][201] were in possession of the city of Edessa in the ancient Near East for a significant period of time. Edessa was located in the region of Osroene, which was an ancient kingdom that existed from the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE. They established a dynasty known as the Abgarids, which ruled Edessa for several centuries. The most famous ruler of the dynasty was Abgar V, who is said to have corresponded with Jesus Christ and is believed to have converted to Christianity.[202] The Abgarids played an important role in the early history of Christianity in the region, and Edessa became a center of Christian learning and scholarship.[203] The Kingdom of Hatra was an ancient city located in the region of Mesopotamia, it was founded in the 2nd or 3rd century BCE and flourished as a major center of trade and culture during the Parthian Empire. The rulers of Hatra were known as the Arsacid dynasty, which was a branch of the Parthian ruling family. However, in the 2nd century CE, the Arab tribe of Banu Tanukh seized control of Hatra and established their own dynasty. The Arab rulers of Hatra assumed the title of "malka," which means king in Arabic, and they often referred to themselves as the "King of the Arabs."[204]

The Osroeni and Hatrans were part of several Arab groups or communities in upper Mesopotamia, which also included the Arabs of Adiabene which was an ancient kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, its chief city was Arbela (Arba-ilu), where Mar Uqba had a school, or the neighboring Hazzah, by which name the later Arabs also called Arbela.[205][206] This Arab presence in upper Mesopotamia was acknowledged by the Sasanians, who called the region Arbayistan, meaning "land of the Arabs", is first attested as a province in the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht inscription of the second Sasanian King of Kings, Shapur I (r. 240–270),[207] which was erected in c. 262.[208][86] The Emesene were a dynasty of Arab priest-kings that ruled the city of Emesa (modern-day Homs, Syria) in the Roman province of Syria from the 1st century CE to the 3rd century CE. The dynasty is notable for producing a number of high priests of the god El-Gabal, who were also influential in Roman politics and culture. The first ruler of the Emesene dynasty was Sampsiceramus I, who came to power in 64 CE. He was succeeded by his son, Iamblichus, who was followed by his own son, Sampsiceramus II. Under Sampsiceramus II, Emesa became a client kingdom of the Roman Empire, and the dynasty became more closely tied to Roman political and cultural traditions.[209]

Late antiquity

[edit]The Ghassanids, Lakhmids and Kindites were the last major migration of pre-Islamic Arabs out of Yemen to the north. The Ghassanids increased the Semitic presence in then-Hellenized Syria, the majority of Semites were Aramaic peoples. They mainly settled in the Hauran region and spread to modern Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan. Greeks and Romans referred to all the nomadic population of the desert in the Near East as Arabi. The Romans called Yemen "Arabia Felix".[210] The Romans called the vassal nomadic states within the Roman Empire Arabia Petraea, after the city of Petra, and called unconquered deserts bordering the empire to the south and east Arabia Magna.

The Lakhmids as a dynasty inherited their power from the Tanukhids, the mid Tigris region around their capital Al-Hira. They ended up allying with the Sassanids against the Ghassanids and the Byzantine Empire. The Lakhmids contested control of the Central Arabian tribes with the Kindites with the Lakhmids eventually destroying the Kingdom of Kinda in 540 after the fall of their main ally Himyar. The Persian Sassanids dissolved the Lakhmid dynasty in 602, being under puppet kings, then under their direct control.[211] The Kindites migrated from Yemen along with the Ghassanids and Lakhmids, but were turned back in Bahrain by the Abdul Qais Rabi'a tribe. They returned to Yemen and allied themselves with the Himyarites who installed them as a vassal kingdom that ruled Central Arabia from "Qaryah Dhat Kahl" (the present-day called Qaryat al-Faw). They ruled much of the Northern/Central Arabian peninsula, until they were destroyed by the Lakhmid king Al-Mundhir, and his son 'Amr.

The Ghassanids were an Arab tribe in the Levant in the early third century. According to Arab genealogical tradition, they were considered a branch of the Azd tribe. They fought alongside the Byzantines against the Sasanians and Arab Lakhmids. Most Ghassanids were Christians, converting to Christianity in the first few centuries, and some merged with Hellenized Christian communities. After the Muslim conquest of the Levant, few Ghassanids became Muslims, and most remained Christian and joined Melkite and Syriac communities within what is now Jordan, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon.[212] The Salihids were Arab foederati in the 5th century, were ardent Christians, and their period is less documented than the preceding and succeeding periods due to a scarcity of sources. Most references to the Salihids in Arabic sources derive from the work of Hisham ibn al-Kalbi, with the Tarikh of Ya'qubi considered valuable for determining the Salihids' fall and the terms of their foedus with the Byzantines.[213]

Middle Ages

[edit]

During the Middle Ages, Arab civilization flourished and the Arabs made significant contributions to the fields of science, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, and literature, with the rise of great cities like Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordoba, they became centers of learning, attracting scholars, scientists, and intellectuals.[214][215] Arabs forged many empires and dynasties, most notably, the Rashidun Empire, the Umayyad Empire, the Abbasid Empire, the Fatimid Empire, among others. These empires were characterized by their expansion, scientific achievements, and cultural flourishing, extended from Spain to India.[214] The region was vibrant and dynamic during the Middle Ages and left a lasting impact on the world.[215]

The rise of Islam began when Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to Medina in an event known as the Hijra. Muhammad spent the last ten years of his life engaged in a series of battles to establish and expand the Muslim community. From 622 to 632, he led the Muslims in a state of war against the Meccans.[216] During this period, the Arabs conquered the region of Basra, and under the leadership of Umar, they established a base and built a mosque there. Another conquest was Midian, but due to its harsh environment, the settlers eventually moved to Kufa. Umar successfully defeated rebellions by various Arab tribes, bringing stability to the entire Arabian peninsula and unifying it. Under the leadership of Uthman, the Arab empire expanded through the conquest of Persia, with the capture of Fars in 650 and parts of Khorasan in 651.[217] The conquest of Armenia also began in the 640s. During this time, the Rashidun Empire extended its rule over the entire Sassanid Empire and more than two-thirds of the Eastern Roman Empire. However, the reign of Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth caliph, was marred by the First Fitna, or the First Islamic Civil War, which lasted throughout his rule. After a peace treaty with Hassan ibn Ali and the suppression of early Kharijite disturbances, Muawiyah I became the Caliph.[218] This marked a significant transition in leadership.[217][219]

Arab empires

[edit]Rashidun era (632–661)

[edit]After the death of Muhammad in 632, Rashidun armies launched campaigns of conquest, establishing the Caliphate, or Islamic Empire, one of the largest empires in history. It was larger and lasted longer than the previous Arab empire Tanukhids of Queen Mawia or the Arab Palmyrene Empire. The Rashidun state was a completely new state and unlike the Arab kingdoms of its century such as the Himyarite, Lakhmids or Ghassanids.

During the Rashidun era, the Arab community expanded rapidly, conquering many territories and establishing a vast Arab empire, which is marked by the reign of the first four caliphs, or leaders, of the Arab community.[220] These caliphs are Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali, who are collectively known as the Rashidun, meaning "rightly guided." The Rashidun era is significant in Arab and Islamic history as it marks the beginning of the Arab empire and the spread of Islam beyond the Arabian Peninsula. During this time, the Arab community faced numerous challenges, including internal divisions and external threats from neighboring empires.[220][221]

Under the leadership of Abu Bakr, the Arab community successfully quelled a rebellion by some tribes who refused to pay Zakat, or Islamic charity. During the reign of Umar ibn al-Khattab, the Arab empire expanded significantly, conquering territories such as Egypt, Syria, and Iraq. The reign of Uthman ibn Affan was marked by internal dissent and rebellion, which ultimately led to his assassination. Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad, succeeded Uthman as caliph but faced opposition from some members of the Islamic community who believed he was not rightfully appointed.[220] Despite these challenges, the Rashidun era is remembered as a time of great progress and achievement in Arab and Islamic history. The caliphs established a system of governance that emphasized justice and equality for all members of the Islamic community. They also oversaw the compilation of the Quran into a single text and spread Arabic teachings and principles throughout the empire. Overall, the Rashidun era played a crucial role in shaping Arab history and continues to be revered by Muslims worldwide as a period of exemplary leadership and guidance.[222]

Umayyad era (661–750 and 756–1031)

[edit]In 661, the Rashidun Caliphate fell into the hands of the Umayyad dynasty and Damascus was established as the empire's capital. The Umayyads were proud of their Arab identity and sponsored the poetry and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. They established garrison towns at Ramla, Raqqa, Basra, Kufa, Mosul and Samarra, all of which developed into major cities.[223] Caliph Abd al-Malik established Arabic as the Caliphate's official language in 686.[224] Caliph Umar II strove to resolve the conflict when he came to power in 717, demanding that all Muslims be treated as equals, but his intended reforms did not take effect, as he died after only three years of rule. By now, discontent with the Umayyads swept the region and an uprising occurred in which the Abbasids came to power and moved the capital to Baghdad.

Umayyads expanded their Empire westwards capturing North Africa from the Byzantines. Before the Arab conquest, North Africa was conquered or settled by various people including Punics, Vandals and Romans. After the Abbasid Revolution, the Umayyads lost most of their territories with the exception of Iberia.

Their last holding became known as the Emirate of Córdoba. It was not until the rule of the grandson of the founder of this new emirate that the state entered a new phase as the Caliphate of Córdoba. This new state was characterized by an expansion of trade, culture and knowledge, and saw the construction of masterpieces of al-Andalus architecture and the library of Al-Hakam II which housed over 400,000 volumes. With the collapse of the Umayyad state in 1031 CE, al-Andalus was divided into small kingdoms.[225]

Abbasid era (750–1258 and 1261–1517)

[edit]

The Abbasids were the descendants of Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, one of the youngest uncles of Muhammad and of the same Banu Hashim clan. The Abbasids led a revolt against the Umayyads and defeated them in the Battle of the Zab effectively ending their rule in all parts of the Empire with the exception of al-Andalus. In 762, the second Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur founded the city of Baghdad and declared it the capital of the Caliphate. Unlike the Umayyads, the Abbasids had the support of non-Arab subjects.[223] The Islamic Golden Age was inaugurated by the middle of the 8th century by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to the newly founded city of Baghdad. The Abbasids were influenced by the Quranic injunctions and hadith such as "The ink of the scholar is more holy than the blood of martyrs" stressing the value of knowledge.

During this period the Abbasid Empire became an intellectual centre for science, philosophy, medicine and education as the Abbasids championed the cause of knowledge and established the "House of Wisdom" in Baghdad. Rival dynasties such as the Fatimids of Egypt and the Umayyads of al-Andalus were also major intellectual centres with cities such as Cairo and Córdoba rivaling Baghdad.[226] In the 13th-century, the Mongols conquered Baghdad in 1258 and killed the Caliph Al-Musta'sim. Members of the Abbasid royal family escaped the massacre and resorted to Cairo, which had broken from the Abbasid rule two years earlier; the Mamluk generals taking the political side of the kingdom while Abbasid Caliphs were engaged in civil activities and continued patronizing science, arts and literature.

Fatimid era (909–1171)

[edit]

The Fatimid caliphate was founded by al-Mahdi Billah, a descendant of Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad, the Fatimid Caliphate was a Shia that existed from 909 to 1171 CE. The empire was based in North Africa, with its capital in Cairo, and at its height, it controlled a vast territory that included parts of modern-day Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Syria, and Palestine. The Fatimid state took shape among the Kutama, in the West of the North African littoral, in Algeria, in 909 conquering Raqqada, the Aghlabid capital. In 921 the Fatimids established the Tunisian city of Mahdia as their new capital. In 948 they shifted their capital to Al-Mansuriya, near Kairouan in Tunisia, and in 969 they conquered Egypt and established Cairo as the capital of their caliphate.

The Fatimids were known for their religious tolerance and intellectual achievements, they established a network of universities and libraries that became centers of learning in the Islamic world. They also promoted the arts, architecture, and literature, which flourished under their patronage. One of the most notable achievements of the Fatimids was the construction of the Al-Azhar Mosque and Al-Azhar University in Cairo. Founded in 970 CE, it is one of the oldest universities in the world and remains an important center of Islamic learning to this day. The Fatimids also had a significant impact on the development of Islamic theology and jurisprudence. They were known for their support of Shia Islam and their promotion of the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam. Despite their many achievements, the Fatimids faced numerous challenges during their reign. They were constantly at war with neighboring empires, including the Abbasid Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire. They also faced internal conflicts and rebellions, which weakened their empire over time. In 1171 CE, the Fatimid Caliphate was conquered by the Ayyubid dynasty, led by Saladin. Although the Fatimid dynasty came to an end, its legacy continued to influence Arab-Islamic culture and society for centuries to come.[227]

Ottoman era (1517–1918)

[edit]

From 1517 to 1918, The Ottomans defeated the Mamluk Sultanate in Cairo, and ended the Abbasid Caliphate in the battles of Marj Dabiq and Ridaniya. They entered the Levant and Egypt as conquerors, and brought down the Abbasid caliphate after it lasted for many centuries. In 1911, Arab intellectuals and politicians from throughout the Levant formed al-Fatat ("the Young Arab Society"), a small Arab nationalist club, in Paris. Its stated aim was "raising the level of the Arab nation to the level of modern nations." In the first few years of its existence, al-Fatat called for greater autonomy within a unified Ottoman state rather than Arab independence from the empire. Al-Fatat hosted the Arab Congress of 1913 in Paris, the purpose of which was to discuss desired reforms with other dissenting individuals from the Arab world.[228] However, as the Ottoman authorities cracked down on the organization's activities and members, al-Fatat went underground and demanded the complete independence and unity of the Arab provinces.[229]

The Arab Revolt was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire during World War I, began in 1916, led by Sherif Hussein bin Ali, the goal of the revolt was to gain independence for the Arab lands under Ottoman rule and to create a unified Arab state. The revolt was sparked by a number of factors, including the Arab desire for greater autonomy within the Ottoman Empire, resentment towards Ottoman policies, and the influence of Arab nationalist movements. The Arab Revolt was a significant factor in the eventual defeat of the Ottoman Empire. The revolt helped to weaken Ottoman military power and tie up Ottoman forces that could have been deployed elsewhere. It also helped to increase support for Arab independence and nationalism, which would have a lasting impact on the region in the years to come.[230][231] The Empire's defeat and the occupation of part of its territory by the Allied Powers in the aftermath of World War I, the Sykes–Picot Agreement had a significant impact on the Arab world and its people. The agreement divided the Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire into zones of control for France and Britain, ignoring the aspirations of the Arab people for independence and self-determination.[232]

Renaissance

[edit]The Golden Age of Arab Civilization known as the "Islamic Golden Age", traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.[233][234][235] The period is traditionally said to have ended with the collapse of the Abbasid caliphate due to Siege of Baghdad in 1258.[236] During this time, Arab scholars made significant contributions to fields such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy. These advancements had a profound impact on European scholars during the Renaissance.[237]

The Arabs shared its knowledge and ideas with Europe, including translations of Arabic texts.[238] These translations had a significant impact on culture of Europe, leading to the transformation of many philosophical disciplines in the medieval Latin world. Additionally, the Arabs made original innovations in various fields, including the arts, agriculture, alchemy, music, and pottery, and traditional star names such as Aldebaran, scientific terms like alchemy (whence also chemistry), algebra, algorithm, etc. and names of commodities such as sugar, camphor, cotton, coffee, etc.[239][240][241][242]

From the medieval scholars of the Renaissance of the 12th century, who had focused on studying Greek and Arabic works of natural sciences, philosophy, and mathematics, rather than on such cultural texts. Arab logician, most notably Averroes, had inherited Greek ideas after they had invaded and conquered Egypt and the Levant. Their translations and commentaries on these ideas worked their way through the Arab West into Iberia and Sicily, which became important centers for this transmission of ideas. From the 11th to the 13th century, many schools dedicated to the translation of philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic to Medieval Latin were established in Iberia, most notably the Toledo School of Translators. This work of translation from Arab culture, though largely unplanned and disorganized, constituted one of the greatest transmissions of ideas in history.[243]

During the Timurid Renaissance spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries, there was a significant exchange of ideas, art, and knowledge between different cultures and civilizations. Arab scholars, artists, and intellectuals played a role in this cultural exchange, contributing to the overall intellectual atmosphere of the time. They participated in various fields, including literature, art, science, and philosophy.[244] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Arab Renaissance was a cultural and intellectual movement that emerged. The term "Nahda" means "awakening" or "renaissance" in Arabic, and refers to a period of renewed interest in Arabic language, literature, and culture.[245][246][247]

Modern period

[edit]

The modern period in Arab history refers to the time period from the late 19th century to the present day. During this time, the Arab world experienced significant political, economic, and social changes. One of the most significant events of the modern period was the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the end of Ottoman rule led to the emergence of new nation-states in the Arab world.[248][249]

Sharif Hussein was supposed, in the event of the success of the Arab revolution and the victory of the Allies in World War I, to be able to establish an independent Arab state consisting of the Arabian Peninsula and the Fertile Crescent, including Iraq and the Levant. He aimed to become "King of the Arabs" in this state, however, the Arab revolution only succeeded in achieving some of its objectives, including the independence of the Hejaz and the recognition of Sharif Hussein as its king by the Allies.[250]

Arab nationalism emerged as a major movement in the early 20th century, with many Arab intellectuals, artists, and political leaders seeking to promote unity and independence for the Arab world.[252] This movement gained momentum after World War II, leading to the formation of the Arab League and the creation of several new Arab states. Pan-Arabism that emerged in the early 20th century and aimed to unite all Arabs into a single nation or state. It emphasized on a shared ancestry, culture, history, language and identity and sought to create a sense of pan-Arab identity and solidarity.[253][254]

The roots of pan-Arabism can be traced back to the Arab Renaissance or Al-Nahda movement of the late 19th century, which saw a revival of Arab culture, literature, and intellectual thought. The movement emphasized the importance of Arab unity and the need to resist colonialism and foreign domination. One of the key figures in the development of pan-Arabism was the Egyptian statesman and intellectual, Gamal Abdel Nasser, who led the 1952 revolution in Egypt and became the country's president in 1954. Nasser promoted pan-Arabism as a means of strengthening Arab solidarity and resisting Western imperialism. He also supported the idea of Arab socialism, which sought to combine pan-Arabism with socialist principles. Similar attempts were made by other Arab leaders, such as Hafez al-Assad, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, Faisal I of Iraq, Muammar Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein, Gaafar Nimeiry and Anwar Sadat.[255]

Many proposed unions aimed to create a unified Arab entity that would promote cooperation and integration among Arab countries. However, the initiatives faced numerous challenges and obstacles, including political divisions, regional conflicts, and economic disparities.[256] The United Arab Republic (UAR) was a political union formed between Egypt and Syria in 1958, with the goal of creating a federal structure that would allow each member state to retain its identity and institutions. However, by 1961, Syria had withdrawn from the UAR due to political differences, and Egypt continued to call itself the UAR until 1971, when it became the Arab Republic of Egypt. In the same year the UAR was formed, another proposed political union, the Arab Federation, was established between Jordan and Iraq, but it collapsed after only six months due to tensions with the UAR and the 14 July Revolution. A confederation called the United Arab States, which included the UAR and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, was also created in 1958 but dissolved in 1961.[257] Later attempts to create a political and economic union among Arab countries included the Federation of Arab Republics, which was formed by Egypt, Libya, and Syria in the 1970s but dissolved after five years due to political and economic challenges. Muammar Gaddafi, the leader of Libya, also proposed the Arab Islamic Republic with Tunisia, aiming to include Algeria and Morocco,[258] instead the Arab Maghreb Union was formed in 1989.[259]

During the latter half of the 20th century, many Arab countries experienced political upheaval and conflicts, including, revolutions. The Arab-Israeli conflict remains a major issue in the region, and has resulted in ongoing tensions and periodic outbreaks of violence. In recent years, the Arab world has faced new challenges, including economic and social inequalities, demographic changes, and the impact of globalization.[260] The Arab Spring was a series of pro-democracy uprisings and protests that swept across several countries in the Arab world in 2010 and 2011. The uprisings were sparked by a combination of political, economic, and social grievances and called for democratic reforms and an end to authoritarian rule. While the protests resulted in the downfall of some long-time authoritarian leaders, they also led to ongoing conflicts and political instability in other countries.[261]

Identity

[edit]Arab identity is defined independently of religious identity, and pre-dates the spread of Islam, with historically attested Arab Christian kingdoms and Arab Jewish tribes. Today, however, most Arabs are Muslim, with a minority adhering to other faiths, largely Christianity, but also Druze and Baháʼí.[262][263] Paternal descent has traditionally been considered the main source of affiliation in the Arab world when it comes to membership into an ethnic group or clan.[264]

Arab identity is shaped by a range of factors, including ancestry, history, language, customs, and traditions.[265] Arab identity has been shaped by a rich history that includes the rise and fall of empires, colonization, and political turmoil. Despite the challenges faced by Arab communities, their shared cultural heritage has helped to maintain a sense of unity and pride in their identity.[266] Today, Arab identity continues to evolve as Arab communities navigate complex political, social, and economic landscapes. Despite this, the Arab identity remains an important aspect of the cultural and historical fabric of the Arab world, and continues to be celebrated and preserved by communities around the world.[267]

Subgroups

[edit]

Arab tribes are prevalent in the Arabian Peninsula, Mesopotamia, Levant, Egypt, Maghreb, the Sudan region and Horn Africa.[268][266][269]

The Arabs of the Levant are traditionally divided into Qays and Yaman tribes. The distinction between Qays and Yaman dates back to the pre-Islamic era and was based on tribal affiliations and geographic locations.; they include Banu Kalb, Kinda, Ghassanids, and Lakhmids.[270] The Qays were made up of tribes such as Banu Kilab, Banu Tayy, Banu Hanifa, and Banu Tamim, among others. The Yaman, on the other hand, were composed of tribes such as Banu Hashim, Banu Makhzum, Banu Umayya, and Banu Zuhra, among others.

There are also many Arab tribes indigenous to Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Iran, including from well before the Muslim conquest of Persia in 633 CE.[271] The largest group of Iranian Arabs are the Khuzestani Arabs, including Banu Ka'b, Bani Turuf and the Musha'sha'iyyah sect. Smaller groups are the Khamseh nomads in Fars province and the Khorasani Arabs. As a result of the centuries-long Arab migration to the Maghreb, various Arab tribes (including Banu Hilal, Banu Sulaym and Maqil) also settled in the Maghreb and formed the sub-tribes which exist to present-day. The Banu Hilal spent almost a century in Egypt before moving to Libya, Tunisia and Algeria, and another century later moved to Morocco.[272]

According to Arab traditions, tribes are divided into different divisions called Arab skulls, which are described in the traditional custom of strength, abundance, victory, and honor. A number of them branched out, which later became independent tribes (sub-tribes). The majority of Arab tribes are descended from these major tribes.[273][274][275][276][277]

They are:[275]

- Bakr, has descendants in Arabia and Iraq.[278]

- Kinanah, has descendants in Arabia, Iraq, Egypt, Sudan, Palestine, Tunisia, Morocco, and Syria.[279]

- Hawazin, has descendants in Arabia, Libya, Algeria, Morocco, Sudan, and Iraq.[280][281][282]

- Tamim, has descendants in Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Palestine, Algeria, and Morocco[283]

- Azd, has descendants in Arabia, Iraq, Levant, and North Africa.[284]

- Ghatafan, has descendants in Arabia and the Maghreb.[285]

- Madhhaj, has descendants in Arabia and Iraq.[286]

- Abd al-Qays, has descendants in Arabia.

- Al Qays (القيس), has descendants in Arabia.

- Quda'a, has descendants in Arabia, Syria, and North Africa.

Geographic distribution

[edit]Arab homeland

[edit]

The total number of Arabs living in the Arab nations is estimated at 366 million by the CIA Factbook (as of 2014). The estimated number of Arabs in countries outside the Arab League is estimated at 17.5 million, yielding a total of close to 384 million. The Arab world stretches around 13,000,000 square kilometres (5,000,000 sq mi), from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast.

Arab diaspora

[edit]Arab diaspora refers to descendants of the Arab immigrants who, voluntarily or as refugees, emigrated from their native lands in non-Arab countries, primarily in East Africa, South America, Europe, North America, Australia and parts of South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and West Africa. According to the International Organization for Migration, there are 13 million first-generation Arab migrants in the world, of which 5.8 million reside in Arab countries. Arab expatriates contribute to the circulation of financial and human capital in the region and thus significantly promote regional development. In 2009, Arab countries received a total of US$35.1 billion in remittance in-flows and remittances sent to Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon from other Arab countries are 40 to 190 per cent higher than trade revenues between these and other Arab countries.[287] The 250,000 strong Lebanese community in West Africa is the largest non-African group in the region.[288][289] Arab traders have long operated in Southeast Asia and along the East Africa's Swahili coast. Zanzibar was once ruled by Omani Arabs.[290] Most of the prominent Indonesians, Malaysians, and Singaporeans of Arab descent are Hadhrami people with origins in southern Arabia in the Hadramaut coastal region.[291]

Europe

[edit]There are millions of Arabs living in Europe, mostly concentrated in France (about 6,000,000 in 2005[292]). Most Arabs in France are from the Maghreb but some also come from the Mashreq areas of the Arab world. Arabs in France form the second largest ethnic group after French people.[293] In Italy, Arabs first arrived on the southern island of Sicily in the 9th century. The largest modern societies on the island from the Arab world are Tunisians and Moroccans, who make up 10.9% and 8% respectively of the foreign population of Sicily, which in itself constitutes 3.9% of the island's total population.[294] The modern Arab population of Spain numbers 1,800,000,[295][296][297][298] and there have been Arabs in Spain since the early 8th century when the Muslim conquest of Hispania created the state of Al-Andalus.[299][300][301] In Germany the Arab population numbers over 1,401,950.[302][303] in the United Kingdom between 366,769[304] and 500,000,[305] and in Greece between 250,000 and 750,000[306]). In addition, Greece is home to people from Arab countries who have the status of refugees (e.g. refugees of the Syrian civil war).[307] In the Netherlands 180,000,[38] and in Denmark 121,000. Other countries are also home to Arab populations, including Norway, Austria, Bulgaria, Switzerland, North Macedonia, Romania and Serbia.[308] As of late 2015, Turkey had a total population of 78.7 million, with Syrian refugees accounting for 3.1% of that figure based on conservative estimates. Demographics indicated that the country previously had 1,500,000[309] to 2,000,000 Arab residents,[12] Turkey's Arab population is now 4.5 to 5.1% of the total population, or approximately 4–5 million people.[12][310]

Americas

[edit]Arab immigration to the United States began in significant numbers during the 1880s, and today, an estimated 2 million Americans trace their roots to an Arab background according the Census Bureau.[20][311] Arab Americans are found in every state, but more than two thirds of them live in just ten states, and one-third live in Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York City specifically.[312][313] Most Arab Americans were born in the US, and nearly 82% of US-based Arabs are citizens.[314][315][316][317]

Arab immigrants began to arrive in Canada in small numbers in 1882. Their immigration was relatively limited until 1945, after which time it increased progressively, particularly in the 1960s and thereafter.[318] According to the website "Who are Arab Canadians", Montreal, the Canadian city with the largest Arab population, has approximately 267,000 Arab inhabitants.[319]

Latin America has the largest Arab population outside of the Arab World.[320] Latin America is home to anywhere from 17–25 to 30 million people of Arab descent, which is more than any other diaspora region in the world.[321][322] The Brazilian and Lebanese governments claim there are 7 million Brazilians of Lebanese descent.[323][324] Also, the Brazilian government claims there are 4 million Brazilians of Syrian descent.[323][7][325][326][327][328] Other large Arab communities includes Argentina (about 3,500,000[14][329][330])

The interethnic marriage in the Arab community, regardless of religious affiliation, is very high; most community members have only one parent who has Arab ethnicity.[331] Colombia (over 3,200,000[332][333][334]), Venezuela (over 1,600,000),[25][335] Mexico (over 1,100,000),[336] Chile (over 800,000),[337][338][339] and Central America, particularly El Salvador, and Honduras (between 150,000 and 200,000).[340][31][32] Arab Haitians (257,000[341]) a large number of whom live in the capital are more often than not, concentrated in financial areas where the majority of them establish businesses.[342]

Caucasus

[edit]

In 1728, a Russian officer described a group of Arab nomads who populated the Caspian shores of Mughan (in present-day Azerbaijan).[343] It is believed that these groups migrated to the South Caucasus in the 16th century.[344] The 1888 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica also mentioned a certain number of Arabs populating the Baku Governorate of the Russian Empire.[345] They retained an Arabic dialect at least into the mid-19th century,[346] there are nearly 30 settlements still holding the name Arab (for example, Arabgadim, Arabojaghy, Arab-Yengija, etc.). From the time of the Arab conquest of the South Caucasus, continuous small-scale Arab migration from various parts of the Arab world occurred in Dagestan. The majority of these lived in the village of Darvag, to the north-west of Derbent. The latest of these accounts dates to the 1930s.[344] Most Arab communities in southern Dagestan underwent linguistic Turkicisation, thus nowadays Darvag is a majority-Azeri village.[347][348]

Central, South, East and Southeast Asia

[edit]According to the History of Ibn Khaldun, the Arabs that were once in Central Asia have been either killed or have fled the Tatar invasion of the region.[349] However, today many people in Central Asia identify as Arabs. Most Arabs of Central Asia are fully integrated into local populations, and sometimes call themselves the same as locals (for example, Tajiks, Uzbeks) but they use special titles to show their Arab origin such as Sayyid, Khoja or Siddiqui.[350]

There are only two communities in India which claim Arab descent, the Chaush of the Deccan region and the Chavuse of Gujarat.[352][353] These groups are largely descended from Hadhrami migrants who settled in these two regions in the 18th century. However, neither community still speaks Arabic, although the Chaush have seen re-immigration to Eastern Arabia and thus a re-adoption of Arabic.[354] In South Asia, where Arab ancestry is considered prestigious, some communities have origin myths that claim Arab ancestry. Several communities following the Shafi'i madhab (in contrast to other South Asian Muslims who follow the Hanafi madhab) claim descent from Arab traders like the Konkani Muslims of the Konkan region, the Mappilla of Kerala, and the Labbai and Marakkar of Tamil Nadu and a few Christian groups in India that claim and have Arab roots are situated in the state of Kerala.[355] South Asian Iraqi biradri may have records of their ancestors who migrated from Iraq in historical documents. The Sri Lankan Moors are the third largest ethnic group in Sri Lanka, constituting 9.2% of the country's total population.[356] Some sources trace the ancestry of the Sri Lankan Moors to Arab traders who settled in Sri Lanka at some time between the 8th and 15th centuries.[357][358][359] There are about 118,866 Arab-Indonesians[360] of Hadrami descent in the 2010 Indonesian census.[361]

Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]

Afro-Arabs are individuals and groups from Africa who are of partial Arab descent. Most Afro-Arabs inhabit the Swahili Coast in the African Great Lakes region, although some can also be found in parts of the Arab world.[362][363] Large numbers of Arabs migrated to West Africa, particularly Côte d'Ivoire (home to over 100,000 Lebanese),[364] Senegal (roughly 30,000 Lebanese),[365] Sierra Leone (roughly 10,000 Lebanese today; about 30,000 prior to the outbreak of civil war in 1991), Liberia, and Nigeria.[366] Since the end of the civil war in 2002, Lebanese traders have become re-established in Sierra Leone.[367][368][369] The Arabs of Chad occupy northern Cameroon and Nigeria (where they are sometimes known as Shuwa), and extend as a belt across Chad and into Sudan, where they are called the Baggara grouping of Arab ethnic groups inhabiting the portion of Africa's Sahel. There are 171,000 in Cameroon, 150,000 in Niger[370]), and 107,000 in the Central African Republic.[371]

Religion

[edit]Arabs are mostly Muslims with a Sunni majority and a Shia minority, one exception being the Ibadis, who predominate in Oman.[372] Arab Christians generally follow Eastern Churches such as the Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches, though a minority of Protestant Church followers also exists.[373] There are also Arab communities consisting of Druze and Baháʼís.[374][375] Historically, there were also sizeable populations of Arab Jews around the Arab World.

Before the coming of Islam, most Arabs followed a pagan religion with a number of deities, including Hubal,[376] Wadd, Allāt,[377] Manat, and Uzza. A few individuals, the hanifs, had apparently rejected polytheism in favor of monotheism unaffiliated with any particular religion. Some tribes had converted to Christianity or Judaism. The most prominent Arab Christian kingdoms were the Ghassanid and Lakhmid kingdoms.[378] When the Himyarite king converted to Judaism in the late 4th century,[379] the elites of the other prominent Arab kingdom, the Kindites, being Himyirite vassals, apparently also converted (at least partly). With the expansion of Islam, polytheistic Arabs were rapidly Islamized, and polytheistic traditions gradually disappeared.[380][381]

Today, Sunni Islam dominates in most areas, vastly so in Levant, North Africa, West Africa and the Horn of Africa. Shia Islam is dominant in Bahrain and southern Iraq while northern Iraq is mostly Sunni. Substantial Shia populations exist in Lebanon, Yemen, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia,[382] northern Syria and Al-Batinah Region in Oman. There are small numbers of Ibadi and non-denominational Muslims too.[372] The Druze community is concentrated in Levant.[383]

Christianity had a prominent presence In pre-Islamic Arabia among several Arab communities, including the Bahrani people of Eastern Arabia, the Christian community of Najran, in parts of Yemen, and among certain northern Arabian tribes such as the Ghassanids, Lakhmids, Taghlib, Banu Amela, Banu Judham, Tanukhids and Tayy. In the early Christian centuries, Arabia was sometimes known as Arabia heretica, due to its being "well known as a breeding-ground for heterodox interpretations of Christianity."[384] Christians make up 5.5% of the population of Western Asia and North Africa.[385] In Lebanon, Christians number about 40.5% of the population.[386] In Syria, Christians make up 10% of the population.[387] Christians in Palestine make up 8% and 0.7% of the populations, respectively.[388][389] In Egypt, Christians number about 10% of the population. In Iraq, Christians constitute 0.1% of the population.[390]

In Israel, Arab Christians constitute 2.1% (roughly 9% of the Arab population).[391] Arab Christians make up 8% of the population of Jordan.[392] Most North and South American Arabs are Christian,[393] so are about half of the Arabs in Australia who come particularly from Lebanon, Syria and Palestine. One well known member of this religious and ethnic community is Saint Abo, martyr and the patron saint of Tbilisi, Georgia.[394] Arab Christians also live in holy Christian cities such as Nazareth, Bethlehem and the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem and many other villages with holy Christian sites.

Culture

[edit]

Arab culture is shaped by a long and rich history that spans thousands of years, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arabs have adopted throughout their history and the various empires and kingdoms that have ruled and took lead of the Arabic civilization have contributed to the ethnogenesis and formation of modern Arab culture. Language, literature, gastronomy, art, architecture, music, spirituality, philosophy and mysticism are all part of the cultural heritage of the Arabs.[395]

Language

[edit]

Arabic is a Semitic language of the Afro-Asiatic family.[396] The first evidence for the emergence of the language appears in military accounts from 853 BCE. Today it has developed widely used as a lingua franca for more than 500 million people. It is also a liturgical language for 1.7 billion Muslims.[397][398] Arabic is one of six official languages of the United Nations,[399] and is revered in Islam as the language of the Quran.[397][400]

Arabic has two main registers. Classical Arabic is the form of the Arabic language used in literary texts from Umayyad and Abbasid times (7th to 9th centuries). It is based on the medieval dialects of Arab tribes. Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the direct descendant used today throughout the Arab world in writing and in formal speaking, for example, prepared speeches, some radio broadcasts, and non-entertainment content,[401] while the lexis and stylistics of Modern Standard Arabic are different from Classical Arabic. There are also various regional dialects of colloquial spoken Arabic that both vary greatly from both each other and from the formal written and spoken forms of Arabic.[402]

Mythology

[edit]

Arabic mythology comprises the ancient beliefs of the Arabs. Prior to Islam the Kaaba of Mecca was covered in symbols representing the myriad demons, djinn, demigods, or simply tribal gods and other assorted deities which represented the polytheistic culture of pre-Islamic. It has been inferred from this plurality an exceptionally broad context in which mythology could flourish.[403][404]

The most popular beasts and demons of Arabian mythology are Bahamut, Dandan, Falak, Ghoul, Hinn, Jinn, Karkadann, Marid, Nasnas, Qareen, Roc, Shadhavar, Werehyena and other assorted creatures which represented the profoundly polytheistic environment of pre-Islamic.[405]

The most prominent symbol of Arabian mythology is the Jinn or genie.[406] Jinns are supernatural beings that can be good or evil.[407][408] They are not purely spiritual, but are also physical in nature, being able to interact in a tactile manner with people and objects and likewise be acted upon. The jinn, humans, and angels make up the known sapient creations of God.[409]

Ghouls also feature in the mythology as a monster or evil spirit associated with graveyards and consuming human flesh.[410][411] In Arabic folklore, ghouls belonged to a diabolic class of jinn and were said to be the offspring of Iblīs, the prince of darkness in Islam. They were capable of constantly changing form, but always retained donkey's hooves.[412]

Literature

[edit]

The Quran, the main holy book of Islam, had a significant influence on the Arabic language, and marked the beginning of Arabic literature. Muslims believe it was transcribed in the Arabic dialect of the Quraysh, the tribe of Muhammad.[413][414] As Islam spread, the Quran had the effect of unifying and standardizing Arabic.[413]

Not only is the Quran the first work of any significant length written in the language, but it also has a far more complicated structure than the earlier literary works with its 114 suwar (chapters) which contain 6,236 ayat (verses). It contains injunctions, narratives, homilies, parables, direct addresses from God, instructions and even comments on how the Quran will be received and understood. It is also admired for its layers of metaphor as well as its clarity, a feature which is mentioned in An-Nahl, the 16th surah.

Al-Jahiz (born 776, in Basra – December 868/January 869) was an Arab prose writer and author of works of literature, Mu'tazili theology, and politico-religious polemics. A leading scholar in the Abbasid Caliphate, his canon includes two hundred books on various subjects, including Arabic grammar, zoology, poetry, lexicography, and rhetoric. Of his writings, only thirty books survive. Al-Jāḥiẓ was also one of the first Arabian writers to suggest a complete overhaul of the language's grammatical system, though this would not be undertaken until his fellow linguist Ibn Maḍāʾ took up the matter two hundred years later.[415]

There is a small remnant of pre-Islamic poetry, but Arabic literature predominantly emerges in the Middle Ages, during the Islamic Golden Age.[416] Imru' al-Qais was a king and poet in the 6th century, he was the last king of Kindite. He is among the finest Arabic poetry to date, as well sometimes considered the father of Arabic poetry.[417] Kitab al-Aghani by Abul-Faraj was called by the 14th-century historian Ibn Khaldun the register of the Arabs.[418] Literary Arabic is derived from Classical Arabic, based on the language of the Quran as it was analyzed by Arabic grammarians beginning in the 8th century.[419]

A large portion of Arabic literature before the 20th century is in the form of poetry, and even prose from this period is either filled with snippets of poetry or is in the form of saj or rhymed prose.[420] The ghazal or love poem had a long history being at times tender and chaste and at other times rather explicit.[421] In the Sufi tradition the love poem would take on a wider, mystical and religious importance.

Arabic epic literature was much less common than poetry, and presumably originates in oral tradition, written down from the 14th century or so. Maqama or rhymed prose is intermediate between poetry and prose, and also between fiction and non-fiction.[422] Maqama was an incredibly popular form of Arabic literature, being one of the few forms which continued to be written during the decline of Arabic in the 17th and 18th centuries.[423]

Arabic literature and culture declined significantly after the 13th century, to the benefit of Turkish and Persian. A modern revival took place beginning in the 19th century, alongside resistance against Ottoman rule. The literary revival is known as al-Nahda in Arabic, and was centered in Egypt and Lebanon. Two distinct trends can be found in the nahda period of revival.[424]

The first was a neo-classical movement which sought to rediscover the literary traditions of the past, and was influenced by traditional literary genres—such as the maqama—and works like One Thousand and One Nights. In contrast, a modernist movement began by translating Western modernist works—primarily novels—into Arabic.[425] A tradition of modern Arabic poetry was established by writers such as Francis Marrash, Ahmad Shawqi and Hafiz Ibrahim. Iraqi poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab is considered to be the originator of free verse in Arabic poetry.[426][427][428]

Cuisine

[edit]

Arab cuisine is largely divided into Khaleeji cuisine, Levantine cuisine and Maghrebi cuisine.[429] Arab cuisine has influenced other cuisines various cultures, including Ottoman, Persian, and Andalusian.

It is characterized by a variety of herbs and spices, including cumin, coriander, cinnamon, sumac, za'atar, cardamom, mint, saffron, sesame, thyme turmeric and parsley.[430][431] Arab cuisine is also known for its sweets and desserts, such as Knafeh, Baklava, Halva, and Qatayef. Arabic coffee, or qahwa, is a traditional drink that is served with dates.

Art

[edit]Arabic art has taken various forms, including, among other things, jewelry, textiles and architecture.[432][433] Arabic script has also traditionally been heavily embellished with often colorful Arabic calligraphy, with one notable and widely used example being Kufic script.[434] Arabic miniatures (Arabic: الْمُنَمْنَمَات الْعَرَبِيَّة, Al-Munamnamāt al-ʿArabīyah) are small paintings on paper, usually book or manuscript illustrations but also sometimes separate artworks that occupy entire pages. The earliest example dates from around 690 CE, with a flourishing of the art from between 1000 and 1200 CE in the Abbasid caliphate. The art form went through several stages of evolution while witnessing the fall and rise of several Arab caliphates.

Arab miniaturists got totally assimilated and subsequently disappeared due to the Ottoman occupation of the Arab world. Nearly all forms of Islamic miniatures (Persian miniatures, Ottoman miniatures and Mughal miniatures) owe their existences to Arabic miniatures, as Arab patrons were the first to demand the production of illuminated manuscripts in the Caliphate, it was not until the 14th century that the artistic skill reached the non-Arab regions of the Caliphate.[435][436][437][438][439]

Despite the considerable changes in Arabic miniature style and technique, even during their last decades, the early Umayyad Arab influence could still be noticed. Arabic miniature artists include Ismail al-Jazari, who illustrated his own Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices.[440]

The Abbasid artist, Yahya Al-Wasiti, who probably lived in Baghdad in the late Abbasid era (12th to 13th-centuries), was one of the pre-eminent exponents of the Baghdad school. In the period 1236–1237, he transcribed and illustrated the book Maqamat (also known as the Assemblies or the Sessions), a series of anecdotes of social satire written by Al-Hariri of Basra.[441] The narrative concerns the travels of a middle-aged man as he uses his charm and eloquence to swindle his way across the Arabic world.[442]

With most surviving Arabic manuscripts in western museums,[443] Arabic miniatures occupy very little space in modern Arab culture.[444] Arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines,[445] often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foliate ornament, typically using leaves, derived from stylised half-palmettes, which were combined with spiralling stems".[446] It usually consists of a single design which can be 'tiled' or seamlessly repeated as many times as desired.[447][448]

Architecture

[edit]The Arab world is home to around 8%[449] of UNESCO World Heritage Sites (List of World Heritage Sites in Arab states). The oldest examples of architecture include those of pre-Islamic Arabia,[450] as well as Nabataean architecture that developed in the ancient kingdom of the Nabataeans, a nomadic Arab tribe that controlled a significant portion of the Middle East from the 4th century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[451][452] The Nabataeans were known for their skill in carving out elaborate buildings, tombs, and other structures from the sandstone cliffs of the region. One of the most famous examples of Nabataean architecture is the city of Petra, which is located in modern-day Jordan, was the capital of the Nabataean kingdom and is renowned for its impressive rock-cut architecture.[453]

Prior to the start of the Arab conquests, Arab tribal client states, the Lakhmids and Ghassanids, were located on the borders of the Sassanid and Byzantine empires and were exposed to the cultural and architectural influences of both.[454][455] They most likely played a significant role in transmitting and adapting the architectural traditions of these two empires to the later Arab Islamic dynasties.[456][457]

The Arab empire expanded rapidly, and with it, came a diverse range of architectural influences. One of the most notable architectural achievements of the Arab Empire is the Great Mosque of Damascus in Syria, which was built in the early 8th century, was constructed on the site of a Christian basilica and incorporated elements of Byzantine and Roman architecture, such as arches, columns, and intricate mosaics. Another important architectural is the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, which was built in the late 7th century. The mosque features an impressive dome and a large prayer hall, as well as intricate geometric patterns and calligraphy on the walls.[458][459]

Music

[edit]