Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of revolutions and rebellions

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

This is a list of revolutions, rebellions, insurrections, and uprisings.

BC

[edit]- Revolutionary/rebel victory

- Revolutionary/rebel defeat

- Another result (e.g. a treaty or peace without a clear result, status quo ante bellum, result unknown or indecisive)

- Ongoing conflict

| Date | Revolution/Rebellion | Location | Revolutionaries/Rebels | Result | Image | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2730 BCE | Set rebellion | Egypt | Priests of Horus | Egypt divides into Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt |

|

[1] |

| c. 2690 BC | Nubian revolt | Nubians | Pharaoh Khasekhemwy quashed the rebellion, reuniting Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt |

|

[2] | |

| c. 2380 BC | Sumerian revolt | Lagash, Sumer | Sumerians | The popular revolt deposed King Lugalanda and put the reformer Urukagina on the throne. |

|

[3] |

| 1046 BC | Battle of Muye | End of the Shang dynasty; beginning of the Zhou dynasty |

|

|||

| 1042–1039 BC | Rebellion of the Three Guards | Three Guards, separatists and Shang loyalists | Decisive Zhou loyalist victory, Fengjian system established, Resistance of Shang loyalists is broken. |

|

[5] | |

| 842 BC | Compatriots Rebellion | Peasants and soldiers | King Li of Zhou was exiled and China was ruled by the Gonghe Regency until Li's death. |

|

[6][7] | |

| 626–620 BC | Revolt of Babylon | The Babylonians overthrew Assyrian rule, establishing the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which ruled over the Near East for about a century. |

|

[8] | ||

| 570 BC | Amasis revolt | Egyptian soldiers | Pharaoh Apries was overthrown and exiled, giving Amasis II the opportunity to seize the throne. Apries later attempted to retake Egypt, with Babylonian support, but was defeated and killed. |

|

[9] | |

| 552–550 BC | Persian Revolt | Persis, Media | Persians, led by Cyrus the Great | Median rule overthrown, Persis and Media become part of the new Achaemenid Empire |

|

|

| 522 BC | Anti-Achaemeneid Rebellions | Assyrians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Elamites, Medians and Parthians | Darius the Great quashes all the rebellions within the space of a year. |

|

[10] | |

| 510–509 BC | Roman Revolution | Republicans | The Roman monarchy was overthrown and in its place the Roman Republic was established. | [11] | ||

| 508–507 BC | Athenian Revolution | Democrats | The Tyrant Hippias was deposed and the subsequent aristocratic oligarchy overthrown, establishing Democracy in Athens. |

|

[12] | |

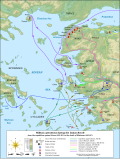

| 499–493 BC | Ionian Revolt | Ionia, |

Greeks | The Achaemenid Empire asserts its rule over the city states of Ionia. |

|

[13] |

| 494 BC | First secessio plebis | Plebeians | Patricians freed some of the plebs from their debts and conceded some of their power by creating the office of the Tribune of the Plebs. |

|

[14] | |

| 484 BC | Bel-shimanni's rebellion | Babylon, |

Rebellion quickly defeated by Xerxes I. | [15] | ||

| 482–481 BC | Shamash-eriba's rebellion | Babylon, |

Rebellion eventually defeated by Xerxes I, Babylon's fortifications were destroyed and its temples were ransacked. | [15] | ||

| 464 BC | Third Messenian War | Messenian Helots | Slave revolt put down by Archidamus II, who called Sparta to arms in the wake of an earthquake. | [16] | ||

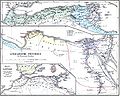

| 460–454 BC | Inaros' revolt | Egypt, |

Inaros II and his Athenian allies | Defeated by the Persian army led by Megabyzus and Artabazus, after a two-year siege. Inaros was captured and carried away to Susa where he was crucified. |

|

[17][18] |

| 449 BC | Second Secessio plebis | Plebeians | The Senate forced the resignation of the Decemviri and restored both the office of Tribune of the Plebs and the right of appeal, which were suspended during the rule of the Decemvir. |

|

[19][20] | |

| 445 BC | Third Secessio plebis | Plebeians | Intermarriage between Patricians and Plebeians was legalized and the position of Consular Tribune (a Tribune of the Plebs elected with the powers of a consul) was created. | [21][22] | ||

| 351 BC | Phoenician revolt of 351 | Phoenicia | Tennes of Sidon, followed by rulers of Anatolia and Cyprus | Destruction of Sidon, execution of Tennes, and invasion of Egypt. | [23][24] | |

| 342 BC | Fourth Secessio plebis | Plebeians | [21] | |||

| 287 BC | Fifth Secessio plebis | Plebeians | The Lex Hortensia was implemented, establishing that the laws decided by the Plebeian Council were made binding on all Roman citizens, including patricians. This law finally eliminated the political disparity between the two classes, bringing the Conflict of Orders to an end after about two hundred years of struggle. | [25] | ||

| 241 BC | Revolt of the Falisci | Falisci | The Falisci were defeated and subjugated to Roman dominance, the town of Falerii was destroyed. |

|

[26] | |

| 209 BC | Dazexiang uprising | Villagers led by Chen Sheng and Wu Guang | The uprising was put down by Qin forces, Chen and Wu were assassinated by their own men. |

|

[27] | |

| 206 BC | Liu Bang's Insurrection | Han forces | The Qin dynasty is overthrown in a popular revolt and after a period of contention, Liu Bang is crowned Emperor of the Han dynasty. |

|

||

| 205–185 BC | Great revolt of the Egyptians | Egypt, |

Egyptians, led by Hugronaphor and Ankhmakis | Revolt put down by the Ptolemaic Kingdom, cementing Greek rule over Egypt. |

|

[28] |

| 181–179 BC | First Celtiberian War | Hispania, |

Celtiberians | Revolt eventually subdued by the Romans. |

|

[29] |

| 167–160 BC | Maccabean Revolt | Judea, Coele-Syria, |

Sovereignty of Judea is secured, eventually the independent Hasmonean dynasty is established. |

|

[30] | |

| 154 BC | Rebellion of the Seven States | Principalities led by Liu Pi | Rebellion crushed after 3 months, further centralization of imperial power. |

|

[31] | |

| 154–151 BC | Second Celtiberian War | Hispania, |

Celtiberians | Rome increased its influence in Celtiberia |

|

[32] |

| 143–133 BC | Numantine War | Hispania, |

Celtiberians | Expansion of the Roman territory through Celtiberia. |

|

[33] |

| 155–139 BC | Lusitanian War | Lusitania, |

Lusitanians, led by Viriatus. | Pacification of Lusitania |

|

[34] |

| 135–132 BC | First Servile War | Sicily, |

Sicilian slaves, led by Eunus | After some minor battles won by the slaves, a larger Roman army arrived in Sicily and defeated the rebels. |

|

[35] |

| 125 BC | Fregellae's revolt | Fregellae, |

Fregellaeans | Fregellae was captured and destroyed by Lucius Opimius |

|

[36] |

| 104–100 BC | Second Servile War | Sicily, |

Sicilian slaves, led by Salvius Tryphon | The revolt was quelled, and 1,000 slaves who surrendered were sent to fight against beasts in the arena back at Rome for the amusement of the populace. To spite the Romans, they refused to fight and killed each other quietly with their swords, until the last flung himself on his own blade. |

|

[37] |

| 91–88 BC | Social War | Italy, |

Italic peoples | Eventually resulted in a Roman victory. However, Rome granted Roman citizenship to all of its Italian allies, to avoid another costly war. |

|

[38] |

| 88 BC | Sulla's first march on Rome | Italy, |

Populares | The Optimates were victorious and Sulla briefly took power in Rome. |

|

[39] |

| 82–81 BC | Sulla's civil war | Italy, |

Populares | The Optimates were once again victorious and Sulla established himself as Dictator of Rome. |

|

[40] |

| 80–71 BC | Sertorian War | Hispania, |

Populares | The war ended after the Populares leader Quintus Sertorius was assassinated by Marcus Perperna Vento, who was then promptly defeated by Pompey. |

|

[41] |

| 77 BC | Lepidus' rebellion | Italy, |

Populares | Lepidus was defeated in battle and died from illness, other Populares fled to Spain to fight in the Sertorian War. |

|

[42] |

| 73–71 BC | Third Servile War | Italy, |

Gladiators, led by Spartacus | The armies of Spartacus were defeated by the legions of Marcus Licinius Crassus. |

|

[43][44] |

| 65 BC | First Catilinarian conspiracy | Rome, |

Catiline | Lucius Aurelius Cotta and Lucius Manlius Torquatus remain in power as consuls. |

|

[45] |

| 62 BC | Second Catilinarian conspiracy | Rome, |

Catiline | The plot was exposed, forcing Catiline to flee from Rome. Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida remain in power as consuls. |

|

[46] |

| 52–51 BC | Gallic Wars | Gaul | Gauls, led by Vercingetorix | The Gallic revolt was crushed by Julius Caesar |

|

[47] |

| 49–45 BC | Great Roman Civil War | Populares, led by Julius Caesar | Caesar defeated the Optimates, assumed control of the Roman Republic and became Dictator in perpetuity. |

|

[48] | |

| 38 BC | Aquitanian revolt | Gallia Narbonensis, |

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa | Revolt suppressed by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. |

|

[49] |

| 29 BC | Theban revolt | Thebes, Egypt, |

Egyptians | Revolt suppressed by Cornelius Gallus |

|

[50] |

1–999 AD

[edit]| Date | Revolution/Rebellion | Location | Revolutionaries/Rebels | Result | Image | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–6 | Gaetulian War | Mauretania, Roman Empire | Gaetuli | Revolt suppressed by Cossus Cornelius Lentulus | [51] | |

| 6 | Judas Uprising | Judea, Roman Empire | Zealots led by Judas of Galilee | Riots against the Roman census erupt throughout the country, but others are convinced by the High Priest of Israel to obey the census. |

|

[52] |

| 6–9 | Bellum Batonianum | Illyricum, Roman Empire | Illyrian tribes | Revolt eventually suppressed by the Romans. |

|

[53] |

| 9–16 | Germanic revolt | Germania | Alliance of Germanic tribes, led by Arminius | The Roman legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus were defeated in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, temporarily halting further Roman occupation and colonization. |

|

[54] |

| 14 | Mutiny of the legions | Germania and Illyricum, Roman Empire | Roman legions | Revolt suppressed by Germanicus and Drusus Julius Caesar respectively |

|

[55] |

| 15–24 | Tacfarinas' revolt' | Mauretania, Roman Empire | Musulamii | Revolt suppressed by Publius Cornelius Dolabella |

|

[56] |

| 17–23 | First Red Eyebrow Rebellion | China | Red Eyebrow and Lulin rebels | Xin dynasty overthrown and the Gengshi Emperor is instated on the throne. |

|

[57][58] |

| 24–27 | Second Red Eyebrow Rebellion | China | Red Eyebrow rebels | Revolt suppressed by Liu Xiu's forces and the Eastern Han dynasty is established. |

|

[59][60] |

| 21 | Gaulish debtors' revolt | Gaul, Roman Empire | Treveri and Aedui | The Treveri revolt was put down by Julius Indus and the Aedui revolt was put down by Gaius Silius. |

|

[61] |

| 26 | Thracian revolt | Odrysian kingdom | Thracians | Revolt suppressed by Gaius Poppaeus Sabinus. |

|

[62] |

| 28 | Revolt of the Frisii | Frisia | Frisii | The Roman Empire is driven out of Frisia. |

|

[63] |

| 36 | Revolt of the Cietae | Cappadocia, Roman Empire | Cietae | Rebellion put down by Archelaus of Cilicia. |

|

[64] |

| 40–43 | Trung sisters' rebellion | Lĩnh Nam | Vietnamese led by the Trung Sisters | After brief end to the First Chinese domination of Vietnam, the Han dynasty reconquers the country and begins the Second Chinese domination of Vietnam. |

|

[65] |

| 40–44 | Mauretanian revolt | Mauretania, Roman Empire | Mauri led by Aedemon and Sabalus | Revolt suppressed by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, Mauretania is annexed directly into the empire and split into the Roman provinces of Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis. |

|

[66] |

| 42 | Camillus' revolt | Dalmatia, Roman Empire | Roman legions led by Lucius Arruntius Camillus Scribonianus | Rebellion quickly collapses, Camillus flees to Vis where he takes his own life. |

|

[67] |

| 46–48 | Jacob and Simon uprising | Galilee, Judea, Roman Empire | Zealots | Revolt suppressed, Jacob and Simon executed by Tiberius Julius Alexander. |

|

[68] |

| 60–61 | Boudican revolt | Norfolk, Britain, Roman Empire | Celtic Britons led by Boudica | Revolt crushed by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. |

|

[69] |

| 66–73 | First Jewish–Roman War | Jewish people | Revolt crushed by the Roman Empire, Jerusalem and the Second Temple are destroyed in the process. |

|

[70] | |

| 68 | Vindex's Revolt | Gallia Lugdunensis, Roman Empire | Gaius Julius Vindex | Vindex was defeated in battle by Lucius Verginius Rufus and committed suicide. | [71] | |

| 69 | Colchis uprising | Colchis, Roman Empire | Anicetus | Uprising put down by Roman forces. |

|

[72] |

| 69–70 | Revolt of the Batavi | Batavia | Batavi | Revolt crushed by Quintus Petillius Cerialis and the Batavi again submitted to Roman rule, Batavia is incorporated into the Roman province of Germania Inferior. |

|

[73] |

| 89 | Revolt of Saturninus | Germania Superior, Roman Empire | Lucius Antonius Saturninus | Revolt swiftly crushed by the Roman legions. |

|

[74] |

| 115–117 | Kitos War | Eastern Mediterranean, Roman Empire | Zealots | Revolt crushed by the Roman legions and its leaders executed. |

|

[75] |

| 117 | Mauretanian revolt | Mauretania, Roman Empire | Mauri | Revolt suppressed by Marcius Turbo |

|

|

| 132–135 | Bar Kokhba revolt | Judea, Roman Empire | Jewish people led by Simon bar Kokhba | All-out defeat of the Jewish rebels, followed by wide-scale persecution and genocide of Jewish people and the suppression of Jewish religious and political autonomy. |

|

[76] |

| 172 | Bucolic war | Egypt, Roman Empire | Egyptians led by Isidorus | Revolt suppressed by Avidius Cassius |

|

[77] |

| 184–205 | Yellow Turban Rebellion | China | Yellow Turban Army led by Zhang Jue | The uprising eventually collapsed and was fully suppressed by various warlords of the Eastern Han dynasty. However, the large devolution of power to regional warlords led to the collapse of the Han dynasty not long after. |

|

[78] |

| 185–205 | Heishan secession | Taihang Mountain, China | Heishan bandits | The autonomous confederacy eventually surrendered to the warlord Cao Cao. |

|

[79] |

| 185 | Roman mutiny | Britain, Roman Empire | Roman legions | Mutiny suppressed by Pertinax. |

|

[80] |

| 218 | Battle of Antioch | Antioch, Syria, Roman Empire | Elagabalus | Elagabalus overthrows Macrinus and is installed as Roman Emperor. |

|

[81] |

| 225–248 | Lady Triệu's uprising | Vietnam | Vietnamese led by Lady Triệu | After several months of warfare Lady Triệu was defeated and committed suicide. The Second Chinese domination of Vietnam continues. |

|

[82] |

| 227–228 | Xincheng Rebellion | Cao Wei, China | Meng Da | The revolt was suppressed by Sima Yi, Meng Da was captured and executed. |

|

[83] |

| 251 | Wang Ling's Rebellion | Shouchon, Cao Wei, China | Wang Ling | Wang Ling surrendered to the Wei forces and later committed suicide. |

|

[84] |

| 255 | Guanqiu Jian and Wen Qin's Rebellion | Shouchon, Cao Wei, China | Guanqiu Jian and Wen Qin | Cao Wei is victorious, Guanqiu Jian is slain, Wen Qin and his family fled to Eastern Wu. |

|

[84] |

| 257–258 | Zhuge Dan's Rebellion | Shouchon, Cao Wei, China | Zhuge Dan | Cao Wei is victorious and the Sima clan cements control over the Wei government until its eventual demise. |

|

[84] |

| 284–286 | Gallic peasants' rebellion | Gaul, Roman Empire | Bagaudae | Rebellion crushed by Caesar Maximian, though the Bagaudae movement would persist until the Fall of the Western Roman Empire. |

|

[85] |

| 286–296 | Carausian Revolt | Britain and northern Gaul, Roman Empire | Carausius and Allectus | Revolt suppressed, Britain and Gaul retaken. |

|

[86] |

| 291–306 | War of the Eight Princes | China | Princes of the Sima clan | Sima Yue wins the war and gains influence over the Jin emperor, but Jin authority in northern China severely weakened. |

|

[87] |

| 304–316 | Uprising of the Five Barbarians | North and Southwest China | Five Barbarians (Han-Zhao and Cheng-Han) | Han-Zhao victory in northern China; Cheng-Han victory in southwestern China; Fall of the Western Jin dynasty in northern China; Formation of the Eastern Jin dynasty in southern China. |

|

[88] |

| 293 | Revolt of the Thebaid | Thebaid, Roman Empire | Busiris and Qift | Revolt suppressed by Galerius. |

|

[89] |

| 351–352 | Jewish revolt against Constantius Gallus | Syria Palaestina, Roman Empire | Jewish people | The Romans crush the revolt and destroy several Jewish cities. |

|

[90] |

| 398 | Gildonic War | Africa, |

Comes Gildo | The revolt was subdued by Flavius Stilicho. |

|

[91] |

| 484 | Justa uprising | Samaria, |

Samaritans | Uprising suppressed by Zeno, who rebuilt the church of Saint Procopius in Neapolis and banned the Samaritans from Mount Gerizim. |

|

[92] |

| 495 | Samaritan unrest | Samaria, |

Samaritans | Uprising suppressed by the Byzantines. |

|

[92] |

| 496 | Mazdak's Revolt | Mazdakites | Mazdak successfully converted Kavadh I, before the latter was overthrown by the nobility and the former was executed. |

|

[93] | |

| 529–531 | Ben Sabar Revolt | Samaria, |

Samaritans led by Julianus ben Sabar | The forces of Justinian I quelled the revolt with the help of the Ghassanids; tens of thousands of Samaritans died or were enslaved. The Christian Byzantine Empire thereafter outlawed the Samaritan faith. |

|

[92] |

| 532 | Nika revolt | Constantinople, |

Blue and Green demes | Revolt suppressed, its participants killed and Justinian I's rule over the Byzantine empire is strengthened. |

|

[94] |

| 541 | Vietnamese uprising | Vạn Xuân | Vietnamese led by Lý Nam Đế | The Second Chinese domination of Vietnam is brought to an end, the country declares itself independent as the Kingdom of Vạn Xuân and crowns Lý Nam Đế as the first king of the Early Lý dynasty. |

|

[95] |

| 556 | Samaritan revolt | Samaria, |

Samaritans and Jewish people | Amantius, the governor of the East was ordered to quell the revolt. |

|

[92] |

| 572–578 | Samaritan revolt | Samaria, |

Samaritans and Jewish people | Revolt suppressed, the Samaritan faith was outlawed and from a population of nearly a million, the Samaritan community dwindled to near extinction. |

|

[92] |

| 608–610 | Heraclian revolt | Exarchate of Africa, |

Heraclius the Elder | Phocas executed and Heraclius the Younger is installed as Byzantine Emperor, establishing the Heraclian dynasty. |

|

[96] |

| 611–617 | Anti-Sui rebellions | China | Former Sui officials and peasant rebels | The Sui dynasty is overthrown, followed by the rise of rebel leader Li Yuan, founder of the Tang dynasty. |

|

[97] |

| 614–625 | Jewish revolt against Heraclius | Palaestina Prima, |

Jewish people | After Palestine was retaken by the Byzantines, Jewish people were massacred and expelled from the region. |

|

[98] |

| 623/624/626 | Samo's rebellion | Avar Khaganate | Slavs led by Samo | Avar rule overthrown, Slavic tribes in the area unify to form Samo's Empire. |

|

[99] |

| 632–633 | Ridda wars | Arabia, |

Arab tribes | Rebels forced to submit to the caliphate of Abu Bakr. |

|

[100] |

| 656–661 | First Fitna | Umayyads | Hasan ibn Ali negotiates a treaty acknowledging Mu'awiya I as caliph, establishing the Umayyad Caliphate. |

|

[101] | |

| 680–692 | Second Fitna | Zubayrids, Alids and Kharijites | The Umayyad Caliphate increases its own power, restructuring the army and Arabizing and Islamizing the state bureaucracy. |

|

[102] | |

| 696–698 | Sufri revolt | Central Iraq, |

Sufri led by Shabib ibn Yazid al-Shaybani | Defeated by the caliphate, although Sufrism continued to be practiced in Mosul. |

|

[103] |

| 700–703 | Ibn al-Ash'ath's rebellion | Iraq, |

Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath | Revolt suppressed by the caliphate, signalling the end of the power of the tribal nobility of Iraq, which henceforth came under the direct control of the Umayyad regime's staunchly loyal Syrian troops. |

|

[104] |

| 720–729 | Yazid's mutiny | Basra, |

Yazid ibn al-Muhallab | Revolt suppressed by the caliphate. | [105] | |

| 713–722 | Annam uprising | Vietnam | Vietnamese led by Mai Thúc Loan | The independent kingdom was put down by a military campaign at the order of the Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, continuing the Third Chinese domination of Vietnam |

|

[106] |

| 734–746 | Harith's rebellion | Khurasan, |

Al-Harith ibn Surayj | Harith is killed and the rebellion crushed, although the revolt weakened Arab power in Central Asia and facilitated the beginning of the Abbasid Revolution. | [107] | |

| 740 | Zaidi Revolt | Kufa, |

Zayd ibn Ali | The Umayyad governor of Iraq managed to bribe the inhabitants of Kufa which allowed him to break the insurgence, killing Zayd in the process |

|

[108] |

| 740–743 | Berber Revolt | Maghreb, |

Berbers led by Maysara al-Matghari | Umayyads expelled from the Maghreb and several independent Berber states are established in the area. | [109] | |

| 744–747 | Third Fitna | Pro-Yaman Umayyads, Alids led by Abdallah ibn Mu'awiya, Kharijites led by Al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shaybani | Victory of Marwan II and the pro-Qays faction in the inter-Umayyad civil war and anti-Umayyad revolts crushed, although Umayyad authority was now permanently weakened. |

|

[110] | |

| 747–748 | Ibadi revolt | South Arabia, |

Ibadis | Umayyad victory in the Hijaz and the Yemen; though Ibadi autonomy is secured in Hadramawt. |

|

[111] |

| 747–750 | Abbasid Revolution | Abbasids | Abbasid Caliphate established, bringing an end to the privileged status for Arabs and discrimination against non-Arabs. |

|

[107] | |

| 752–760 | Mardaite revolts | Mount Lebanon and |

Lebanese Christians and Byzantine Empire | Christian inhabitants of parts of interior and coastal Lebanon expelled and replaced with Arab tribes. |

|

[112] |

| 754 | Abdallah's rebellion | Syria, |

Abdallah ibn Ali | Abdallah's army is defeated by Abu Muslim. |

|

[113] |

| 755 | Córdoban revolution | Almuñécar, al-Andalus, |

Umayyads led by Abd al-Rahman I | Umayyads take control of al-Andalus, establishing the Emirate of Córdoba. |

|

[114] |

| 755–763 | An Lushan Rebellion | Yan, China | An Lushan | Yan defeated by the Tang imperial forces, although the Tang dynasty was weakened. |

|

[115] |

| 762–763 | Alid Revolt | Hejaz and Southern Iraq, |

Alids led by Muhammad ibn Abdallah | Revolt suppressed by the caliphate, followed by a large-scaled reprisal campaign against the Alids. | [116] | |

| 772–804 | Saxon Wars | Saxony | Saxons | Saxony is annexed into the Frankish empire and the Saxons are forcibly converted from Germanic paganism to Catholicism. |

|

[117] |

| 786 | Alid revolt | Mecca, Hejaz, |

Alids | Revolt crushed by the Abbasid army and members of the Alid house are executed. One of the Alids, Idris ibn Abdallah, fled the battlefield to the Maghreb, where he established the Idrisid dynasty. | [118] | |

| 791–802 | Phùng rebellion | Vietnam | Vietnamese led by Phùng Hưng | Briefly ruled the country before the Third Chinese domination of Vietnam is reestablished. |

|

[119] |

| 793–796 | Qays–Yaman war | Syria, |

Qays | Revolt crushed by the Abbasids and their Yamani allies. |

|

[120] |

| 794–795 | Al-Walid's rebellion | Jazira, |

Kharijites led by Al-Walid ibn Tarif al-Shaybani | Yazid ibn Mazyad al-Shaybani met the rebels in battle in late 795, at al-Haditha above Hit, and defeated al-Walid in single combat, killing him and cutting off his head. Yazid also killed a large number of the Kharijites and forced the remainder to disperse, and the revolt ended in defeat. |

|

[121] |

| 811–838 | Fourth Fitna | Alids led by Muhammad ibn Ja'far al-Sadiq, Qays led by Nasr ibn Shabath al-Uqayli | Al-Ma'mun takes power as Caliph, al-Sadiq is forced into exile, Qays territory is lost and Nasr surrenders to the caliphate, and the Tahirids begin their reign over Khorasan |

|

[122] | |

| 816–837 | Babak Khorramdin Revolt | An uprising or revolt of Khurramites led by Babak Khorramdin against the Abbasid Caliphate in Azerbaijan. | The suppression of the uprising, Babak was captured and executed, with more than 100,000 of his followers killed. |

|

[123] | |

| 814 | al-Ribad rebellion | Guadalquivir, Emirate of Córdoba | Clerics in al-Ribad | Rebellion crushed at Al-Hakam I | [124] | |

| 821–823 | Thomas the Slav's rebellion | Anatolia, |

Thomas the Slav | Thomas is surrendered and executed by the Byzantines | [125] | |

| 824–836 | Tunisian mutiny | Tunisia, Ifriqiya, |

Arabs | Aghlabids put down the revolt with the help of the Berbers |

|

[126] |

| 822 | Aristocratic rebellion | Aristocrats led by Kim Hŏn-ch'ang | The royal faction was able to regain much of the territory that Kim Hŏn-ch'ang's forces had taken. After the fall of Gongju, Kim Hŏn-ch'ang took his own life. |

|

||

| 841–842 | Umayyad rebellion | Palestine, |

Umayyads led by Al-Mubarqa | Al-Hidari defeated al-Mubarqa's forces in a battle near Ramlah, al-Mubarqa taken prisoner and brought to the caliphal capital, Samarra, where he was thrown into prison and never heard of again. |

|

[127] |

| 841–845 | Stellinga | Saxony, Carolingian Empire | Saxon freemen and freedmen | Revolt crushed by the Carolingians and their allies in the Saxon nobility. |

|

[128] |

| 845–846 | Chang Pogo's mutiny | Chang Pogo | Chang Pogo assassinated by an emissary from the Silla court. |

|

[129] | |

| 859–860 | Qiu's rebellion | Zhejiang, China | Peasants led by Qiu Fu | Rebellion was suppressed by the imperial general Wang Shi. |

|

[130] |

| 861–876 | Saffarid revolution | Sistan, Khorasan, |

Saffarids led by Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar | al-Saffar overthrows Abbasid rule over Iran and establishes the Saffarid dynasty. |

|

[131] |

| 864 | Alid uprising | Iraq, |

Alids led by Yahya ibn Umar | The Alids attacked Al-Musta'in's forces, but were defeated and fled, Umar was subsequently executed. |

|

[132] |

| 865–866 | Fifth Fitna | Iraq, |

Al-Mu'tazz | Al-Musta'in deposed as Caliph and succeeded by Al-Mu'tazz. |

|

[133] |

| 866–896 | Kharijite Rebellion | Jazira, |

Kharijites | It was finally defeated after the caliph al-Mu'tadid undertook several campaigns to restore caliphal authority in the region. |

|

[134] |

| 869–883 | Zanj Rebellion | Sawad, |

Zanj | Revolt eventually suppressed by the Abbasids. |

|

[135] |

| 874–884 | Qi rebellion | China | Wang Xianzhi and Huang Chao | Rebellions suppressed by the Tang dynasty, which later collapsed due to the destabilization caused by the rebellion. |

|

[136] |

| 880–928 | Bobastro rebellion | Emirate of Córdoba | Muwallads and Mozarabs led by Umar ibn Hafsun | Ibn Hafsun died in 917, his coalition then crumbled, and while his sons tried to continue the resistance, they eventually fell to Abd-ar-Rahman III, who proclaimed the Caliphate of Córdoba. |

|

[137] |

| 899–906 | The Qarmatian Revolution | Eastern Arabia, |

Qarmatians | Qarmatians successfully establish a republic in Eastern Arabia, becoming the most powerful force in the Persian Gulf. The Qarmatians were eventually reduced to a local power by the Abbasids in 976 and annihilated by the Seljuq-backed Uyunid Emirate in 1076. | [138] | |

| 917–924 | Bulgarian–Serbian war | Balkans | Serbians led by Zaharija | Serbia is annexed into the First Bulgarian Empire. |

|

[139] |

| 928–932 | Bithynian rebellion | Bithynia, |

Basil the Copper Hand | The revolt was finally subdued by the imperial army and Basil was executed. |

|

[140] |

| 943–947 | Ibadi Berber revolt | Ifriqiya, |

Ibadi Berbers led by Abu Yazid | Revolt suppressed by the Fatimids, Abu Yazid captured and killed. |

|

[141] |

| 969–970 | First rebellion of Bardas Phokas the Younger | Caesarea, |

Phokas family | Rebellion extinguished by Bardas Skleros, Phokas was captured and exiled to Chios, where he stayed for 7 years. | [142] | |

| 976–979 | Rebellion of Bardas Skleros | Anatolia, |

Bardas Skleros | Bardas Phokas the Younger recalled from exile to put down Skleros' rebellion at the Battle of Pankaleia, Skleros seeks refuge in Baghdad. |

|

[143] |

| 983 | Great Slav rising | Elbe, Germany, |

Polabian Slavs | Halt to Ostsiedlung. |

|

[144] |

| 987–989 | Second Rebellion of Bardas Phokas the Younger | Anatolia, |

Bardas Phokas the Younger and Bardas Skleros | Rebel armies surrendered after the death of Phokas. |

|

[145] |

| 993–995 | Da Shu rebellion | Sichuan, China | Da Shu Kingdom | The Song dynasty was able to suppress the rebellion and restore their rule over the Shu region. |

|

[146] |

| 996 | Peasants' revolt in Normandy | Norman peasants | Suppression of the rebellion | [147] | ||

| 996-998 | Revolt of Tyre (996–998) | Tyre, Lebanon, |

Tyrians and Byzantine Empire | Revolt suppressed and rebels killed or enslaved | [148] |

1000–1499

[edit]| Date | Revolution/Rebellion | Location | Revolutionaries/Rebels | Result | Image | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1034–1038 | Serb revolt against the Byzantine Empire | Duklja, |

Serbs led by Vojislav of Duklja | Revolt suppressed and Vojislav imprisoned, before starting another rebellion which eventually succeeded | ||

| 1040–1041 | Uprising of Peter Delyan | Balkan peninsula, |

Bulgarians led by Peter Delyan | Rebellion suppressed by Emperor Michael IV |

|

[149] |

| 1072 | Uprising of Georgi Voyteh | Balkan peninsula, |

Bulgarians led by Georgi Voyteh | Revolt suppressed by Damianos Dalassenos |

|

[150] |

| 1090 | Takeover of Alamut | Alamut, Seljuk Empire | Hashshashin led by Hassan-i Sabbah | Nizari Ismaili state founded, creating the Order of Assassins |

|

|

| 1095 | Rebellion of northern nobles against William Rufus | England | Northern nobles led by Robert de Mowbray | Suppression of the rebellion | ||

| 1125 | Almohads against the Almoravids | Atlas Mountains | Masmuda tribes led by Ibn Tumart | Establishment of the Almohad Caliphate | ||

| 1143-1145 | Commune of Rome Uprising | Rome | Commune of Rome | Establishment of the Commune of Rome | ||

| 1156 | Hōgen Rebellion | Japan | Forces loyal to retired Emperor Sutoku | Rebellion suppressed by forces loyal to Emperor Go-Shirakawa. Established the dominance of samurai clans and eventually the first samurai-led government in the history of Japan | ||

| 1185 | Rebellion of Asen and Peter against Byzantine Empire | Balkan Mountains | Bulgarians and Vlachs | Creation of the Second Bulgarian Empire | ||

| 1209–1211 | Quách Bốc Rebellion | Lý dynasty | Army led by General Quách Bốc | Defeat of Emperor Lý Cao Tông and further weakening of the declining Lý dynasty | ||

| 1233–1234 | Stedinger revolt | Frisia | Stedingers | Revolt suppressed by a crusade called by Pope Gregory IX | ||

| 1237–1239 | Babai Revolt | Sultanate of Rum | Rebels | Revolt suppressed | ||

| 1242–1249 | The First Prussian Uprising | Pomerania | Teutonic Knights | Swantopolk II returned seized lands. Knights allowed safe passage in Pomerania. Treaty of Christburg (secured rights for Christians) | ||

| 1250 | Bahri revolt | Egypt | Bahri Mamluks | Mamluks consolidated power and established the Bahri dynasty | ||

| 1282 | Sicilian Vespers | Sicily | Sicilian rebels | Angevin regime overthrown | ||

| 1296–1328 | First Scottish War of Independence | Scotland | Kingdom of Scotland | Renewed Scottish independence | ||

| 1302 | Battle of the Golden Spurs | Flanders | County of Flanders | Flemish victory. French ousted | ||

| 1323–1328 | Peasant revolt in Flanders | Flanders | County of Flanders | Restoration of pro-French court. Repression of rebels | ||

| 1332–1357 | Second Scottish War of Independence | Scotland | Kingdom of Scotland | Treaty of Berwick. Renewed Scottish independence | ||

| 1342 | Zealots of Thessalonica | Byzantine Empire | Zealots of Thessalonica | Zealots ruled Thessalonica for 8 years | ||

| 1343–1345 | St. George's Night Uprising | Estonia | Local Estonians from the Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek | Uprising suppressed | ||

| 1346-1347 | Rebellion of Ismail Mukh | Deccan, |

Ismail Mukh's forces | Rebellion victory, later establishment of the Bahmani Sultanate. | ||

| 1354 | Revolt of Cola di Rienzi | Rome | Cola di Rienzi and loyal forces (with help from Louis I)[151] | Successfully revolted. However, Cola eventually abdicated and left Rome | ||

| 1356–1358 | Jacquerie uprising | Northern France | Peasants | Revolt successfully repressed | ||

| 1368 | Red Turban Rebellions | China | Peasant Han Chinese led by Zhu Yuanzhang | Establishment of the Ming dynasty | ||

| 1378 | Revolt of the Ciompi | Florence | Laborers from Florence | City government seized. Demands of the laborers initially met. Though this would prove to be temporary. |

|

|

| 1378–1384 | Tuchin Revolt | Béziers | Locals from Béziers | Duc de Berry suppressed the revolt | ||

| 1381 | Peasants' Revolt. This was a rebellion in England led by Wat Tyler and John Ball, in which peasants demanded an end to serfdom. | England | Rebels led by Wat Tyler | Wat Tyler killed, revolt suppressed |

|

|

| 1382 | Harelle | Rouen, Paris | Guild members of Rouen | Revolt leaders killed. City rights revoked | ||

| c. 1387 | Isfahan revolt | Isfahan | Local rebels | Revolt violently repressed[152] | ||

| 1400–1415 | Welsh revolt | Wales | Rebels headed by Owain Glyndŵr | England conquered Wales | ||

| 1404/1408/1413^ | Uprising of Konstantin and Fruzhin | Historical region of Bulgaria | Bulgarian nobles | Failure to liberate Bulgaria | ||

| 1418–1427 | Lam Sơn uprising | Northern Vietnam | Rebels led by Lê Lợi | Independence of Đại Việt | ||

| 1421–1432 | Jasrat's rebellion | Delhi Sultanate | Khokhars of Sialkot led by Jasrat | Liberation of Punjab upto Ravi. Later pushed back to Chenab. | ||

| 1431–1435 | First Irmandiño revolt | Galicia | Peasantry and bourgeoisie | Revolt suppressed | ||

| 1434–1436 | Engelbrekt rebellion | Dalarna | Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson | Engelbrekt assassinated. Kalmar Union eroded | ||

| 1437 | Transylvanian peasants revolt | Kingdom of Hungary | Transylvanian peasants and petty nobles | Patrician victory | ||

| 1444–1468 | Skanderbeg's rebellion | Ottoman-ruled Albania | Skanderbeg and his forces | Skanderbeg agreed to peace and paid tribute to the Ottomans. | ||

| 1450 | Jack Cade's Rebellion | Kent, England | Rebels led by Jack Cade | Royal victory | ||

| 1462–1485 | Rebellion of the Remences | Principality of Catalonia | Peasants | Indecisive | ||

| 1467–1470 | Second Irmandiño revolt | Galicia | Peasantry and bourgeoisie | Irmandiño movement defeated | ||

| 1497 | Cornish rebellion of 1497 | England | Rebels mainly from Cornwall | Royal victory |

1500–1699

[edit]| Date | Revolution/Rebellion | Location | Revolutionaries/Rebels | Result | Image | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1499–1501 | Rebellion of the Alpujarras | Kingdom of Granada | Muslims of Granada | Rebellion suppressed and mass forced conversions of all Muslims in Granada | ||

| 1501–1503 | War of Deposition against King Hans | Kalmar Union | Swedish separatists | Separatist victory, Kalmar Union de facto dissolved | ||

| 1501–1504 | Alvsson's rebellion against King Hans of Norway | Denmark and Norway | Norwegian separatists | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1514 | Peasants' war led by György Dózsa | Kingdom of Hungary | Peasants led by György Dózsa | Rebellion suppressed and György Dózsa was executed | ||

| 1515 | Slovene peasant revolt | Holy Roman Empire | Peasants | Revolt put down by Holy Roman Empire mercenaries | ||

| 1515–1523 | Arumer Zwarte Hoop | Habsburg Netherlands | Frisian rebels led by Pier Gerlofs Donia and Wijerd Jelckama. | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1516 | Trần Cảo Rebellion | Lê dynasty | Rebellion suppressed. Lê dynasty weakened by ensuing civil war | |||

| 1519–1523 | Revolt of the Brotherhoods | Valencia | Germanies autonomist rebels | Rebel leader L'Encobert killed and strongholds of the Germanies captured | ||

| 1520–1522 | Revolt of the Comuneros | Royalist Castilians | Comuneros rebels | Royalist victory | ||

| 1521–1522 | Santo Domingo Revolt | Enslaved Africans | Suppression of the revolt | |||

| 1521–1523 | Gustav Vasa's Rebellion | Rebels led by nobleman Gustav Vasa | Rebels successfully deposed King Christian II from the throne of Sweden | |||

| 1524–1525 | German Peasants' War | Suppression of revolt and execution of its participants | ||||

| 1526 | Slave revolt in San Miguel de Gualdape | Rebels | Inconclusive | |||

| 1531 | The Straccioni Rebellion, uprising in Lucca | Rebels | ||||

| 1532–1547 | Sebastián Lemba's rebellion | Rebels led by maroon Sebastián Lemba | Suppression of the revolt | |||

| 1536 | Pilgrimage of Grace | Suppression of the uprisings, execution of the leading figures | ||||

| 1540–1542 | Mixtón War | Caxcanes | Spaniard and indigenous allied victory | |||

| 1542 | Dacke War | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1548 | Revolt of the Pitauds | French peasants against the salt tax | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1548–1582 | Bayano Wars | Enslaved Bayano rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1549 | Prayer Book Rebellion | Catholic rebels in Cornwall and Devon | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1549 | Kett's Rebellion | East Anglian rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1550–1590 | Chichimeca War | Chichimeca Confederation | Chichimeca military victory | |||

| 1567–1872 | Philippine revolts against Spain | Rebels | ||||

| 1568–1571 | Morisco rebellions in Granada | Morisco rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1568–1648 | Eighty Years' War | Peace of Münster | ||||

| 1569–1570 | Rising of the North | Elizabeth I of England | Partisans of Mary, Queen of Scots and Northern English Catholics | Elizabethan victory | ||

| 1570–1618 | Gaspar Yanga's revolt against Spanish colonial rule in Mexico | Rebels led by Gaspar Yanga | Ended with the signing of a treaty with Spain | |||

| 1573 | Croatian–Slovene peasant revolt | Croatian, Styrian and Carniolan nobility and Uskoks | Croatian and Slovene peasants | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1590–1610 | Celali rebellions | Ottoman Empire | Celali rebels | Suppressed by Kuyucu Murad Pasha | ||

| 1591–1594 | Rappenkrieg | Basel | Peasants | Negotiations led to a restriction to tax increases. Insurgents were spared punishment | ||

| 1594–1595 | Croquant rebellion | Limousin | Rebels | Croquants disarmed | ||

| 1594–1603 | Nine Years' War | Irish alliance | English victory | |||

| 1594 | Banat Uprising | Ottoman Empire | Serb rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1596 | Club War | Nobility and army | Peasants and army | Nobility victory | ||

| 1596–1597 | Serb Uprising against the Ottomans | Ottoman Empire | Serb rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1597 | First Guale revolt developed in Florida against the Spanish missions and led by Juanillo | Rebels led by Juanillo | Rebellion suppressed | [153][154] | ||

| 1598 | First Tarnovo uprising | Ottoman Empire | Bulgarian rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1600–1601 | Thessaly rebellion | Ottoman Empire | Greek rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1600–1607 | Acaxee Rebellion | Acaxee | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1606–1607 | Bolotnikov rebellion | Tsardom of Russia | Rebels led by Bolotnikov | Rebellion suppressed |

|

|

| 1616–1620 | Tepehuán Revolt | Tepehuánes | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1618–1625 | Bohemian Revolt |

|

Imperial victory | |||

| 1631–1634 | Salt Tax Revolt | Rebels in Biscay | Ringleaders arrested and executed | |||

| 1637–1638 | Shimabara Rebellion | Tokugawa shogunate | Japanese Catholics | Tokugawa victory | [155] | |

| 1639 | Revolt of the va-nu-pieds | Rebels in Normandy | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1640–1668 | Portuguese Revolt | Portuguese victory | ||||

| 1640–1652 | Catalan Revolt | Catalan defeat | ||||

| 1641–1642 | Irish Rebellion of 1641 | Irish victory and the Founding of the Irish Catholic Confederation | ||||

| 1641 | Acclamation of Amador Bueno in the Captaincy of São Vicente, Brazil | Captaincy of São Vicente | [156][157][158] | |||

| 1642–1652 | English Civil War | Parliamentarian victory, Execution of Charles I, establishment of the Commonwealth of England | ||||

| 1644 | Li Zicheng's Uprising | Ming dynasty | Rebels led by Li Zicheng | Overthrow of the Ming dynasty and the establishment of the Shun dynasty | ||

| 1647 | Naples Revolt | Neapolitan Republic | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1648 | Khmelnytsky uprising | Emergence of Cossack Hetmanate under Russian protection | ||||

| 1648 | Moscow salt riot | Tsardom of Russia | Rebels | Arrest and execution of many of the leaders of the uprising | ||

| 1648–1653 | Fronde | Parlements | Rebellion suppressed |

|

||

| 1658 | Revolt of Abaza Hasan Pasha | Ottoman Empire | Rebels led by Abaza Hasan Pasha | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1659 | Bakhtrioni uprising | Strategically inconclusive | ||||

| 1662–1664 | Bashkir rebellion | Tsardom of Russia | Bashkir rebels | Demands of the rebels met | ||

| 1664–1670 | Magnate conspiracy | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1667–1668 | First Revolt of the Angelets | Vallespir | Anti-salt tax rebels | Compromise of Céret. Tax inspectors ended controls | ||

| 1668–1676 | Solovetsky Monastery uprising | Tsardom of Russia | Old Believer monks | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1670–1674 | Second Revolt of the Angelets | Conflent | Rebels against the salt tax | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1672 | Pashtun rebellion | Mughal Empire | Pashtun rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1672–1674 | Lipka rebellion | Tatars' privileges, payments and religious freedoms guaranteed | [159] | |||

| 1672–1678 | Messina Revolt | Sicilian rebels | ||||

| 1674–1680 | Trunajaya rebellion | Rebel forces | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1675 | Revolt of the papier timbré, an anti-tax revolt in Brittany | Rebels in Brittany | ||||

| 1675–1676 | King Philip's War | Native Americans | Confederation victory | |||

| 1676 | Bacon's Rebellion | Colony of Virginia | Virginia colonists, indentured servants and slaves | Change in Virginia's Native American-Frontier policy | ||

| 1680–1692 | Pueblo Revolt | Puebloans | Pueblo victory, expulsion of Spanish settlers | |||

| 1681–1684 | Bashkir rebellion | Tsardom of Russia | Bashkir rebels | Demands of the rebels met | [160] | |

| 1682 | Moscow Uprising | Tsardom of Russia | Streltsy regiments | Sophia suppressed the Streltsy and Tararui in their attempts to remove her from power |

|

|

| 1684 | Beckman's Revolt | Maranhão e Grão-Pará | Manoel Beckman and rebels | Rebellion suppressed | [161][162] | |

| 1685 | Monmouth Rebellion | Monmouth rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1685 | Argyll Rebellion | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1686 | Second Tarnovo uprising | Ottoman Empire | Bulgarian rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1687–1689 | Revolt of the Barretinas | Catalan rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1688 | Chiprovtsi uprising | Ottoman Empire | Catholic Bulgarian rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1688 | Siamese revolution of 1688 | Victory for Phetracha's forces and his Dutch allies | ||||

| 1688 | Glorious Revolution | Rebels | James II replaced as king by his daughter Mary II and her husband William III | |||

| 1688–1746 | Jacobite risings | Jacobites | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1689 | Karposh’s Rebellion | Ottoman Empire | Bulgarian rebels | Rebellion suppressed | [163] | |

| 1689 | Boston revolt | Dissolution of the Dominion of New England; ouster of officials loyal to James II | ||||

| 1693 | Second Brotherhood | Valencia | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1698 | Streltsy uprising | Tsardom of Russia | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed |

1700–1799

[edit]| Date | Revolution/Rebellion | Location | Revolutionaries/Rebels | Result | Image | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1702–1715 | War of the Camisards | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1703–1711 | Rákóczi Uprising | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1707–1709 | Bulavin Rebellion | Tsardom of Russia | Don Cossack rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1707–1709 | Newcomers' War | Captaincy of São Vicente, Brazil | Paulistas | Rebellion suppressed | [164][165] | |

| 1709 | Mirwais Hotak's rebellion against Gurgin Khan, the Persian governor of Kandahar | Rebels led by Mirwais Hotak | rebellion successful | |||

| 1709–1710 | Pablo Presbere's insurrection against Spanish colonial power | Rebels led by Pablo Presbere | ||||

| 1710–1711 | Peddlers' War | Pernambuco, Brazil | Rebels | [166][167] | ||

| 1711 | Cary's Rebellion | Rebels | ||||

| 1712 | Tzeltal Rebellion | indigenous rebels | ||||

| 1712 | New York Slave Revolt of 1712 | Rebel slaves | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1713-1714 | War of the Catalans | Catalan defeat | ||||

| 1715 | First Jacobite rising | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1720 | Vila Rica Revolt | Minas Gerais, Brazil | Rebels | [168][169] | ||

| 1722 | Afghan rebels defeated Shah Sultan Husayn and ended the Safavid dynasty. | Afghan rebels | rebellion successful | |||

| 1728–1740 | First Maroon War | Jamaican Maroons | Maroon victory, the British government offered peace treaties | |||

| 1729 | Natchez revolt | French colonists | the Natchez | |||

| 1731 | Samba rebellion | French Louisiana | Rebel slaves | |||

| 1733–1734 | slave insurrection on St. John | Rebel slaves | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1737–39 | Serb uprising | Serb rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1739 | Stono Rebellion | Escaped slaves | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1741 | New York Conspiracy of 1741 | slaves and poor whites | ||||

| 1743 | Fourth Dalecarlian rebellion | peasants' | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1744–1829 | Dagohoy rebellion | Boholano people | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1745–1746 | Jacobite rising | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1747 | Orangist revolution | |||||

| 1748 | Uprising led by Juan Francisco de León in Panaquire, Venezuela, against monopoly interests and the dominance of the Royal Company Guipuzcoana in terms of trade cocoa | Rebels led by Juan Francisco de León | ||||

| 1749 | Conspiracy of the Slaves | Malta | Rebel slaves | |||

| 1751–1752 | Pima Revolt | |||||

| 1753 | The Lunenburg Rebellion | immigrant rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1755–1769 | The revolution that ended Genoese rule and established a Corsican Republic | Revolution was brought to an end by the French conquest of Corsica | ||||

| 1760 | Tacky's War | Enslaved "Coromantee" people | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1763 | Berbice slave uprising | Society of Berbice Society of Suriname Barbados Navy Dutch Navy | Arawak and Carib allies | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1763–1766 | Pontiac's War | numerous North American Indian tribes | Military stalemate | |||

| 1765 | Quito Revolt of 1765 | Rebels | ||||

| 1765 | Strilekrigen | Norwegian farmers | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1768 | Louisiana Rebellion of 1768 | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1769–1773 | First Carib War | Carib inhabitants of Saint Vincent | ||||

| 1770 | Orlov revolt | Supported by: |

Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1770 | Abdzakh revolution. The Circassians of the Abdzakh region started a great revolution in Circassian territory in 1770. Classes such as slaves, nobles and princes were completely abolished. The Abdzakh Revolution coincides with the French Revolution. While many French nobles took refuge in Russia, some of the Circassian nobles took the same path and took refuge in Russia | Circassians of the Abdzakh region | [170] | |||

| 1771–1785 | Tây Sơn wars | Tây Sơn Cham people Chinese Vietnamese (1771–1777) Pirates of the South China Coast |

Nguyễn lord Chinese Vietnamese (Hoà Nghĩa army) |

Nguyễn lord victory | ||

| 1773–1775 | Pugachev's Rebellion | Coalition of Cossacks, Russian Serfs, Old Believers, and non-Russian peoples | Rebellion suppressed | [171] | ||

| 1775 | Rising of the Priests | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1775–1783 | American Revolutionary War | Revolutionary victory |

|

|||

| 1780–1782 | José Gabriel Condorcanqui, known as Túpac Amaru II, raises an indigenous peasant army in revolt against Spanish control of Peru. Julián Apasa, known as Túpac Katari allied with Túpac Amaru and lead an indigenous revolt in Upper Peru (present-day Bolivia) nearly destroying the city of La Paz in a siege. | Túpac Amaru II | ||||

| 1780–1787 | The Patriot Revolt | Rebels | ||||

| 1781 | Revolt in Bihar | Rebels in Bihar | ||||

| 1781 | Revolt of the Comuneros | Rebels | ||||

| 1782 | Sylhet uprising | Bengali Muslim Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1782 | Geneva Revolution | Republic of Geneva | the third estate | |||

| 1786–1787 | Shays' Rebellion | Shaysites | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1786–1787 | Lofthusreisingen | Norway | Rebels | |||

| 1787 | Abaco Slave Revolt | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1788 | Kočina Krajina Serb rebellion | Serb rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1789–1799 | French Revolution | Revisionaries | Revolutionary victory

|

|||

| 1789–1790 | Brabant Revolution | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1789–1791 | Liège Revolution |

|

Revolutionary victory

|

|||

| 1790 | Saxon Peasants' Revolt | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1790 | The first slave revolt | British Virgin Islands | Rebels | |||

| 1791 | Whiskey Rebellion | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1791 | Mina conspiracy | Rebels | ||||

| 1791–1804 | Haitian Revolution | 1791–1793

|

1791–1793

|

Haitian victory |

| |

| 1792 | War in Defence of the Constitution | Polish defeat | ||||

| 1793 | Slave rebellion produced in the Guadeloupe island following the outbreak of the French Revolution. | Rebels | ||||

| 1793 | Jumla rebellion | Kingdom of Nepal | Sobhan Shahi

People of Jumla |

|||

| 1793–1796 | War in the Vendée | Supported by: |

Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1794 | Kościuszko Uprising | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1794 | Whiskey Rebellion | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1794 | Stäfner Handel uprising | Republic of Zürich | Rebels | |||

| 1795 | Batavian Revolution | Supported by: |

Supported by: |

Revolutionary victory | ||

| 1795 | Curaçao Slave Revolt | Slave rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1795–1796 | 1795–1796: In those years broke out several slave rebellions in the entire Caribbean, influenced by the Haitian Revolution: in Cuba, Jamaica (Second Maroon War), Dominica (Colihault Uprising), Louisiana (Pointe Coupée conspiracy), Saint Lucia (Bush War, so-called "Guerre des Bois"), Saint Vincent (Second Carib War), Grenada (Fédon's rebellion), Curaçao (led by Tula), Guyana (Demerara Rebellion) and in Coro, Venezuela (led by José Leonardo Chirino) | [172] | ||||

| 1796 | Conspiracy of Equals | Rebels | Conspiracy discovered and repressed | |||

| 1796 | Boca de Nigua Revolt | Slave rebels led by Francisco Sopo | ||||

| 1796–1804 | White Lotus Rebellion | Qing dynasty | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||

| 1797 | Spithead and Nore mutinies | Mutineers | ||||

| 1797 | 1797 Rugby School Rebellion | Mutineers | ||||

| 1797 | Scottish Rebellion | Rebels | Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1798 | Irish Rebellion of 1798 | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1798 | The Maltese Revolt in September 1798 against French administration in Malta. The French capitulated in September 1800 after they were blockaded inside the islands' harbour fortifications for two years | Rebels | ||||

| 1798–1804 | James Corcoran's Guerilla Campaign | |||||

| 1799–1800 | Fries's Rebellion | Rebels led by John Fries | ||||

| 1799-1803 | Michael Dwyers Guerilla Campaign | |||||

1800–1849

[edit]| 1803 | Irish rebellion of 1803 | Rebellion suppressed | |||||

| 1804 | Uprising against the Dahije | Serbian victory | |||||

| 1804-13 | First Serbian Uprising | Rebellion suppressed | |||||

| 1809 | Tyrolean Rebellion | Supported by: |

French Victory |

|

|||

| 1809–1825 | Bolivian War of Independence | Royalists: | Patriots: | Patriot Victory | |||

| 1809–1826 | Peruvian War of Independence | Royalists: | Patriots:

Co-belligerents |

Patriot Victory | |||

| 1810 | The House Tax Hartal was an occasion of nonviolent resistance to protest a tax in parts of British India, with a particularly noteworthy example of hartal (a form of general strike) in the vicinity of Varanasi | Demonstrators | |||||

| 1810 | The West Florida rebellion against Spain, eventually becomes a short-lived republic. | Rebels | |||||

| 1810–1821 | Mexican War of Independence | Insurgent victory | |||||

| 1810 | May Revolution | Primera Junta | Primera Junta victory | ||||

| 1810–1818 | Argentine War of Independence | Royalists | Patriots: | Argentine victory and emancipation from Spanish colonial rule | |||

| 1810–1823 | Venezuelan War of Independence | 1810: 1811–1816: 1816–1819: 1819–1823: |

Patriot victory | ||||

| 1810–1826 | Chilean War of Independence | Royalists:

Mapuche allies of the Royalists |

Patriots:

Mapuche allies of the Patriots |

Chilean victory | |||

| 1811 | Paraguayan Revolt | Paraguayan Rebels | Revolt victory | ||||

| 1811 | German Coast uprising | Enslaved Africans | Suppression of uprising | ||||

| 1811 | 1811 Independence Movement | Salvadoran revolutionaries | Rebellion suppressed |

|

|||

| 1812 | The peasant rebellion of Hong Gyeong-nae | Joseon dynasty | Rebels | ||||

| 1812 | Aponte conspiracy | Cuban rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1812 | 1812 Mendoza and Mojarra Conspiracy | Dominican rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1814 | Norwegian War of Independence |

Supported by:

|

Swedish victory | ||||

| 1814 | Hadži Prodan's Revolt | Rebellion suppressed | |||||

| 1815 | George Boxley's slave rebellion in Spotsylvania County, Virginia | Slave rebels | |||||

| 1815–1817 | Second Serbian uprising | Strategic Serbian diplomatic victory; Establishment of the autonomous Principality of Serbia | |||||

| 1816 | Bussa's rebellion | Slave rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1816–1858 | Seminole Wars | Seminole Yuchi Choctaw Freedmen |

American victory | ||||

| 1817 | Pernambucan Revolt | Portuguese victory and resulted in the creation of the short-lived Republic of Pernambuco (7 March 1817 – 20 May 1817). | |||||

| 1817 | Pentrich rising, | Rebels led by William Oliver | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1817 | Paika Rebellion | Bhoi dynasty | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1817–1818 | Uva-Wellassa Rebellion | Rebellion suppressed | |||||

| 1820 | The Revolutions of 1820 were a wave of revolutions attempting to establish liberal constitutional monarchies in Italy, Spain and Portugal. | ||||||

| 1820 | Radical War | Various Groups | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1820–1822 | Ecuadorian War of Independence | Patriot victory. Annexation of the territory to Gran Colombia. | |||||

| 1820–1824 | The revolutionary war of independence in Peru led by José de San Martín | ||||||

| 1821 | Marcos Xiorro's conspiracy to incite a slave revolt in Spanish Puerto Rico | Rebels | |||||

| 1821 | Wallachian uprising |

|

|

|

Ottoman military victory Wallachian political victory

End of the Phanariote Era |

||

| 1821–1829 | Greek War of Independence | 1821:

After 1822: Military support:

Diplomatic support: |

Greek victory | ||||

| 1822 | Denmark Vesey's suppressed slave uprising in South Carolina | Slave rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1822–1823 | The republican revolution in Mexico overthrows Emperor Agustín de Iturbide | Rebels | Rebel victory | ||||

| 1822–1825 | Brazilian War of Independence | Brazilian victory | |||||

| 1823 | Demerara rebellion of 1823 | Rebel slaves | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1824 | Chumash revolt of 1824 | Chumash Native Americans | |||||

| 1825 | Decembrist revolt | Northern Society of the Decembrists | Rebellion suppressed, Decembrists executed or deported to Siberia | ||||

| 1825–1830 | Java War | Javanese rebels | Dutch victory | ||||

| 1826 | Janissary revolts | Janissaries | |||||

| 1826–1827 | Fredonian Rebellion | Rebellion suppressed | |||||

| 1826–1828 | Lao rebellion | Military support: |

Siamese victory | ||||

| 1827–1828 | The failed conservative rebellion in Mexico led by Nicolás Bravo. | rebels led by Nicolás Bravo | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1828–1834 | Liberal Wars | Supported by: |

Supported by:

|

Liberal victory | |||

| 1829 | Bathurst War | Wiradjuri | British victory | ||||

| 1829–1832 | War of the Maidens. Countrymen dressed as women resisted the new forestry law, which restricted their use of the forest |

|

rebels | ||||

| 1830 | The Revolutions of 1830 were a wave of Romantic nationalist revolutions in Europe | ||||||

| 1830–1831 | Belgian Revolution |

|

Belgian victory | ||||

| 1830 | July Revolution | Middle class against Bourbon King Charles X | Charles X which forced him out of office and replaced him with the Orleanist King Louis-Philippe (the "July Monarchy") |

|

|||

| 1830–1831 | November uprising | Congress Poland | Russian victory | ||||

| 1830 | Ustertag revolution | Canton of Zürich | Rebels | ||||

| 1830 | Bathurst Rebellion | Convict rebels | |||||

| 1830–1833 | Yagan's War | Noongar people | |||||

| 1830–1836 | Tithe War | Irish Demonstrators | |||||

| 1831 | Nat Turner's slave rebellion | Insurgents | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1831 | Merthyr Rising | ||||||

| 1831, 1834, 1848 | Canut revolts | Lyonnais silk workers (French: canuts) | |||||

| 1831–1832 | Bosnian uprising | Ottoman victory | |||||

| 1831–1832 | Baptist War | Slave rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1832 | June Rebellion |

|

Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1832–1833 | Anastasio Aquino's Rebellion | Indigenous rebels | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1832–1843 | Abdelkader's rebellion in French-occupied Algeria | Rebels led by Abdelkader | |||||

| 1833–1835 | Lê Văn Khôi revolt | Nguyễn dynasty | Lê Văn Khôi rebels

Supported by: |

Rebellion suppressed | |||

| 1834 | Flores' Rebellion | Nicaragua | Rebels | ||||

| 1834–1859 | Imam Shamil's rebellion in Russian-occupied Caucasus | Rebels | |||||

| 1835–1836 | Texas Revolution | De facto Texian independence from the Centralist Republic of Mexico | |||||

| 1835 | Malê revolt | Malê slaves (primarily Nagôs) | Rebellion suppressed | ||||

| 1835–1840 | The Cabanagem | Rebellion suppressed | |||||

| 1835–1845 | Ragamuffin War |

Supported by: |

Peace treaty between both parties

|

||||

| 1837 | Río Arriba Rebellion | Republic of Mexico | Puebloans | Temporary success:

|

|||

| 1837-1838 | Rebellions of 1837-1838 | Upper Canada | Hunter's Lodges (Upper Canada)

Patriotes (Lower Canada) |

Rebels defeated in both Upper and Lower Canada

Upper and Lower Canada unified into the single Province of Canada |

|||

| 1837-1838 | Sabinada | Empire of Brazil | Bahia Republic, led by Francisco Sabino | Government victory; rebel capital of Salvador captured after four months of resistance | |||

| 1838-1841 | Balaida | Empire of Brazil | Rebels

|

Government victory | |||

| 1839 | Amistad Rebellion | Amistad slave ship | Slaves | Initial slave victory, eventual capture of slaves by the United States

United States v. The Amistad supreme court decision |

|||

| 1839-1843 | Rebecca Riots | Wales | Farmers and agricultural workers | End in riots due to increased military presence

Act of Parliament amends laws relating to turnpike trusts |

|||

| 1841 | Creole revolt | Creole American slave ship | Slaves | Revolt successful | |||

| 1841-1842 | Dorr Rebellion | Rhode Island | Disenfranchised voters led by Thomas Wilson Dorr | Military government victory

Land qualification to vote removed from the state constitution |

|||

| 1841-1842 | Afghan uprising | Kabul, Emirate of Kabul

|

Afghan citizens of Kabul | Afghan victory

|

[178] | ||

| 1842 | Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation | Cherokee Nation | Slaves | Slaves eventually captured and some executed | |||

| 1844–1856 | Dominican War of Independence | Dominican victory | |||||

| 1845-1872 | New Zealand Wars | New Zealand | Māori iwi | Eventual British victory

16000 km2 of Māori land seized in New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863 |

|||

| 1846 | Greater Poland uprising | Greater Poland

|

Poles | Planned revolution never goes through

8 rebels executed |

|||

| 1846 | Kraków uprising | Free City of Kraków, Austrian Empire | Polish resistance | Austrian victory | |||

| 1846 | Bear Flag Revolt | Alta California, Mexico | California Republic | California Republic declared, soon annexed by United States | |||

| 1847-1901 | Caste War of Yucatán | Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico and British Honduras | Maya people | Initial Mayan victory, eventual defeat

|

|||

| 1847 | The Taos Revolt | New Mexico, United States | Hispano and Puebloan rebels | American strategic victory

Mexican tactical victory |

|||

| 1847 | Sonderbund War | Sonderbund | Confederate victory | ||||

| 1848 | French Revolution of 1848 | Monarchy of France | Revolutionaries | Revolutionary victory

|

|||

| 1848-1849 | German revolutions of 1848-1849 | German Confederation | Revolutionaries

The quasi-state of the German Empire |

Rebellion quelled | |||

| 1848 | Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states | Various states in the Italian peninsula | Revolutionaries | Revolutionaries defeated | |||

| 1848 | Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire | Revolutionaries | Counterrevolutionary victory

|

||||

| 1848 | March Unrest | Sweden | Armed protesters | Rebellion quelled | |||

| 1848 | Prague uprising | Prague under the Austrian Empire | Rebels | Rebellion defeated | |||

| 1848 | Greater Poland uprising | Kingdom of Prussia | Rebels seeking Polish independence | Rebellion defeated | |||

| 1848 | Young Ireland rebellion | Ireland under the |

Rebellion defeated | ||||

| 1848-1849 | Serb uprising of 1848–1849 | Southern Kingdom of Hungary | Serbian Vojvodina | Rebel victory

|

|||

| 1848 | Wallachian Revolution of 1848 | Counter-revolutionary victory | |||||

| 1848 | Moldavian Revolution of 1848 | Liberal and nationalist revolutionaries | Counter-revolutionary victory | ||||

| 1848 | Matale rebellion | British victory | |||||

| 1848-1849 | Praieira revolt | Imperial victory | [179] | ||||

1850–1899

[edit]

- 1851–64: The Taiping Rebellion by the God Worshippers against the Qing dynasty of China. In total between 20 and 30 million lives had been lost, making it the second deadliest war in human history.

- 1852: The Kautokeino rebellion in Kautokeino, Norway.

- 1852–62: The Herzegovina Uprising (1852–62) in Ottoman Herzegovina.

- 1853–55: The Small Knife Society rebellion in Shanghai, China.

- 1854: A revolution in Spain against the Moderate Party Government.

- 1854: The Eureka Rebellion (Eureka Stockade) in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. Miners battled British Colonial forces against taxation policies of the Government.

- 1854–56: Peasant Rebel in Vietnam, led by Cao Ba Quat, against the Nguyễn dynasty.

- 1854–56: The Red Turban Rebellion (1854–1856) in Guangdong (Canton), China.

- 1854–73: The Miao Rebellion in China.

- 1854–55: The Revolution of Ayutla in Mexico.

- 1855–1856: The Karakalpak Rebellion by the Karakalpak leader Ernazor Alakoz against the Khanate of Khiva[180][181][182]

- 1855–73: The Panthay Rebellion by Chinese Muslims against the Qing dynasty.

- 1857: The Indian rebellion against British East India Company, marking the end of Mughal rule in India. Also known as the 1857 War of Independence and, particularly in the West, the Sepoy Mutiny.

- 1858: The Mahtra War in Estonia.

- 1858: Pecija's First Revolt, in Ottoman Bosnia.

- 1858–61: The War of the Reform in Mexico.

- 1859: John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, an effort by abolitionist John Brown to initiate an armed slave revolt in Southern states by taking over Harpers Ferry Armory in Virginia.

- 1859: The Second Italian War of Independence.

- 1861–65: The American Civil War in the United States, between the United States and the Confederate States of America, which was formed out of eleven southern states.

- 1863–65: A counter-rebellion occurred in the self-declared Free State of Jones in Mississippi.

- 1861–66: Quantrill's Raiders in Missouri.

- 1862: The Sioux Uprising in Minnesota.[183]

- 1862–77: The Dungan revolt (1862–1877) by Chinese Muslims against the Qing dynasty.

- 1862: The 23 October 1862 Revolution was a popular insurrection which led to the overthrow of King Otto of Greece.

- 1863: The New York Draft riots.[184]

- 1863–65: The January Uprising was the Polish uprising against the Russian Empire.

- 1863–65: The Dominican Restoration War was the Dominican Republic's second war of independence, this time against the Kingdom of Spain.

- 1864–65: The Mejba Revolt was a rebellion in Tunisia against the doubling of an unpopular poll tax imposed by Sadok Bey.

- 1865: The Morant Bay rebellion.

- 1866: The Uprising of Polish political exiles in Siberia.

- 1866–68: The Meiji Restoration and modernization revolution in Japan. Samurai uprising leads to overthrow of shogunate and establishment of "modern" parliamentary, Western-style system.

- 1867: The Fenian Rising: an attempt at a nationwide rebellion by the Irish Republican Brotherhood against British rule.

- 1868: The Glorious Revolution in Spain deposes Queen Isabella II.

- 1868: The Grito de Lares was the first major revolt against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico. The rebels proclaimed the independence of Puerto Rico from Spain.

- 1868–74: The Six Years' War, often called the Dominican Republic's third war of independence, was to disrupt the annexation to the United States.

- 1868–78: Ten Years' War, also known as the Great War (Guerra Grande) and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain, led by Cuban-born planters (especially by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes) and other wealthy natives.

- 1869–70: The Red River Rebellion, the events surrounding the actions of a provisional government established by Métis leader Louis Riel at the Red River Colony, Manitoba, Canada.

- 1870–72: The Revolution of the Lances, the National Party revolts against the Colorado Government in Uruguay.

- 1870–71: Lyon Commune in France.

- 1871: The Paris Commune.

- 1871–72: Porfirio Díaz rebels against President Benito Juárez of Mexico.

- 1871: The liberal revolution in Guatemala.

- 1873: The Petroleum Revolution in the First Spanish Republic.

- 1873–74: The Cantonal rebellion in the First Spanish Republic.

- 1873: The Khivan slave uprising against slavery in the Khanate of Khiva.

- 1875: The Deccan Riots.

- 1875: The Stara Zagora Uprising, a revolt by the Bulgarian population against Ottoman rule.

- 1875–76: The Svaneti uprising of 1875–1876

- 1875–78: The Great Eastern Crisis:

- 1875–77: The Herzegovinian rebellion, the most famous of the rebellions against the Ottoman Empire in Herzegovina; unrest soon spread to other areas of Ottoman Bosnia.

- 1876: The April uprising, a revolt by the Bulgarian population against Ottoman rule.

- 1876: The Razlovtsi insurrection, a revolt by the Bulgarian population against Ottoman rule, part of the April Uprising.

- 1876–78: Serbian-Turkish Wars (1876–1878)

- 1876–78: Montenegrin–Ottoman War (1876–78)

- 1877–78: Romanian War of Independence

- 1878: Kumanovo Uprising

- 1878: Kresna–Razlog uprising, a revolt by the Bulgarian population against Ottoman rule.

- 1878 Greek Macedonian rebellion

- Epirus Revolt of 1878

- Cretan Revolt (1878)

- 1876: The second rebellion by Porfirio Díaz against President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada of Mexico.

- 1877: The Satsuma Rebellion of Satsuma ex-samurai against the Meiji government.

- 1877: Banda del Matese in Italy.

- 1879: Little War (Cuba) or Small War, second of three conflicts between Cuban rebels and Spain. It started on 26 August 1879 and ended in rebel defeat in September 1880.

- 1879–1882: The Urabi Revolt: an uprising in Egypt on 11 June 1882 against the Khedive and European influence in the country. It was led by and named after Colonel Ahmed Urabi.

- 1880–1881: The Brsjak revolt.

- 1883: The Timok Rebellion was a popular uprising that began in eastern Serbia.

- 1885: A peasant revolt in the Ancash region of Peru led by Pedro Pablo Atusparía succeeds in occupying the Callejón de Huaylas for several months.

- 1885–96: Cần Vương movement of Vietnam, led by emperor Hàm Nghi, against French colonialism

- 1885: The North-West Rebellion of Métis in Saskatchewan.

- 1885: Bulgarian unification - accomplished after revolts in Eastern Rumelian towns, followed by a coup.

- 1888: The Peasant Rebellion in Banten, Indonesia.

- 1889: The Republican Revolution in Brazil.

- 1890–1914: The Saminism Movement in Indonesia.

- 1890: Revolution of the Park, Argentina.

- 1892: Jerez uprising in Spain.

- 1893: Revolution of 1893, Argentina

- 1893: A liberal revolt brings José Santos Zelaya to power in Nicaragua.

- 1894: Lunigiana revolt in Italy.

- 1894–95: The Donghak Peasant Revolution: Korean peasants led by Jeon Bong-jun revolted against the Joseon dynasty; the revolt was crushed by Japanese and Chinese intervention, leading to First Sino-Japanese War.

- 1895: The revolution against President Andrés Avelino Cáceres in Peru ushers in a period of stable constitutional rule.

- 1895–1896: The War of Canudos was a conflict between the First Brazilian Republic and the residents of Canudos in the northeastern state of Bahia.

- 1895–1896: The First Italo-Ethiopian War in which Ethiopians fought against Italians colonizers.

- 1895–1898: Cuban War of Independence, the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, being initiated by José Martí.

- 1896: Yaqui Uprising in Sonora and Arizona

- 1896–98: The Philippine Revolution, a war of independence against Spanish rule directed by the Katipunan society.

- 1897: The Intentona de Yauco (Attempted Coup of Yauco), was the second and last major revolt against Spanish colonial rule in Puerto Rico, staged by Puerto Rico's pro-independence movement.

- 1898: The Dukchi Ishan (Andican Uprising): Kirgiz, Uzbek, and Kipcak peoples rebelled against Tsarist Russia in Turkestan (Fargana Valley).

- 1898: The Hut Tax War was a resistance in the newly annexed Protectorate of Sierra Leone to a new, severe tax imposed by the colonial military governor.

- 1898: The Dog Tax War was a confrontation between the Colony of New Zealand and a group of Northern Māori, led by Hone Riiwi Toia, opposed to the enforcement of a 'dog tax'.

- 1898: The Wilmington insurrection of 1898, A mob of white supremacists forced out the city government of Wilmington, North Carolina.[185]

- 1899: The tancament de caixes, a tax revolt in Barcelona.

- 1899–1902: The Philippine–American War, a conflict over sovereignty of the Philippines between the de facto sovereign First Philippine Republic and the nominally sovereign United States.

- 1899–1901: The Boxer Rebellion against foreign influence in areas such as trade, politics, religion and technology that occurred in China during the final years of the Qing dynasty, which was defeated by the Eight-Nation Alliance.

- 1899–1962: The Mau was a non-violent movement for Samoan independence from colonial rule (by Germany and then New Zealand) during the first half of the 20th century.

1900s

[edit]

- 1900: The War of the Golden Stool was a resistance by the Asante of West Africa against the imposition of colonial rule by the United Kingdom.

- 1901–1936: Holy Man's Rebellion.

- 1903: The Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising breaks out in the Ottoman Empire.

- 1904: Revolution of 1904

- 1904: A liberal revolution in Paraguay.

- 1904–1908: Macedonian Struggle.

- 1904–1908: Herero Wars in German South-West Africa.

- 1905: Argentine Revolution of 1905.

- 1905–1906: The Persian/Iranian Constitutional Revolution.

- 1905–1906: The Maji Maji Rebellion in German East Africa.

- 1905: Shoubak Revolt.

- 1905: Łódź insurrection.

- 1905–1907: Revolution in the Kingdom of Poland (1905–07).

- 1905–1906: 1905 Tibetan Rebellion.

- 1905–1907: 1905 Russian Revolution, which was abortive and ultimately crushed, though forming the critical precedent for the 1917 Russian Revolution.

- 1906: Bambatha Rebellion by the Zulus of southern Africa against British rule.

- 1906–1908: Theriso revolt.

- 1907: The Romanian Peasants' Revolt.

- 1908: The Young Turk Revolution: Young Turks force the autocratic ruler Abdul Hamid II to restore parliament and constitution in the Ottoman Empire.

- 1909: HNLMS De Zeven Provinciën (1909).

- 1909: Hauran Druze Rebellion.

1910s

[edit]

- 1910: The republican revolution in Portugal.

- 1910–1920: The Mexican Revolution overthrows the dictator Porfirio Díaz; seizure of power by the National Revolutionary Party (later called Institutional Revolutionary Party).

- 1910: The Albanian Revolt of 1910 against Ottoman centralization policies in Albania.

- 1910–1911: The Sokehs Rebellion erupts in German-ruled Micronesia. Its primary leader, Somatau, is executed soon after being captured.

- 1911–1912: The Xinhai Revolution overthrows the ruling Qing dynasty and establishment of the Republic of China.

- 1911–1912: The East Timorese rebellion against colonial Portugal.

- 1911–1912: The Dominican Civil War (1911–1912) against the Dominican Government.

- 1912: The Albanian Revolt of 1912 against Ottoman Empire rule in Albania.

- 1912-1916: The Contestado War was a guerrilla war for land between settlers and landowners in South Brazil.

- 1913: The Second Revolution against President Yuan Shikai of China.

- 1914: The Ten Days War was a shooting war involving irregular forces of coal miners using dynamite and rifles on one side, opposed to the Colorado National Guard, Baldwin Felts detectives, and mine guards deploying machine guns, cannon and aircraft on the other, occurring in the aftermath of the Ludlow massacre. The Ten Days War ended when federal troops intervened.

- 1914: The Dominican Civil War (1914) against the Dominican Government.

- 1914: The revolt of Peasants of Central Albania overthrows Prince William of Wied.

- 1914–1915: The Boer Revolt against the British in South Africa.

- 1914–1915: Muslim rebellion in Krujë (Albania)

- 1915: The Armenian revolt in city of Van against the Ottomans in Turkey.

- 1915: Somba rebellion (Tammari people)[186]

- 1915–1916: The National Protection War against the Empire of China headed by Emperor Yuan Shikai. The Republic of China was restored.

- 1915–1916: The Tapani incident is the last major Chinese uprising in Taiwan during the Japanese colonial era.